en

names in breadcrumbs

Northern goshawks are considered "management indicators" in many national forests. They are considered "sensitive to change", and their well being often can provide clues to problems with habitat change.

Goshawks, like other accipiters, depend upon vocalizations for communication in their forested habitats. They are especially vocal during courtship and nesting. Both sexes make equally varied sounds, however, the female's sounds are deeper and louder, while male goshawks tend to have higher and less powerful voices. There are also several specific calls, or wails, given by goshawks.

As nestlings, young goshawks may use a "whistle-beg" call as a plea for food. It begins as a ke-ke-ke noise, and progresses to a kakking sound. The chick may also use a high pitched "contentment-twitter" when it is well fed.

As adults, goshawks vocalize by way of wail-calls, which consist of "ki-ki-ki-ki" or "kak, kak, kak". This call varies with the action it represents. A "recognition-wail" is made by both males and females when entering or leaving the nest. A "food-transfer" call, which is harsh sounding, is made by males to demand food from the female.

Northern goshawks also use postures and other physical cues to communicate.

Communication Channels: visual ; acoustic

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Because northern goshawks are threatened in some areas, conservation measures to protect them may negatively impact the logging industry.

Northern goshawks have been used for centuries in falconry. More importantly, northern goshawks help to control populations of small mammal pests.

Positive Impacts: controls pest population

Northern goshawks are important as predators in the ecosystems in which they live, especially to small mammal and bird populations. They are also host to internal and external parasites, including lice, cestods and trematodes.

Northern goshawks are carnivorous, mainly consuming birds, mammals, invertebrates, and reptiles of moderate to large size. Individual prey items can weigh up to half the weight of the goshawk. The content of an individual goshawks diet depends upon the environment in which that goshawk live. The average diet consists of 21 to 59 percent mammals and 18 to 69 percent birds, with the remaining percentages being made up of reptiles and invertebrates. Some common prey include snow-shoe hares, red squirrels, ground squirrels, spruce grouse, ruffed grouse, and blue grouse. Northern goshawks sometimes cache prey on tree branches or wedged in a crotch between branches for up to 32 hours. This is done primarily during the nestling stage.

Animal Foods: birds; mammals; reptiles; insects

Foraging Behavior: stores or caches food

Primary Diet: carnivore (Eats terrestrial vertebrates)

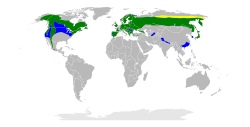

Northern goshawks are found throughout the mountains and forests of North America and Eurasia. In North America they range from western central Alaska and the Yukon territories in the north to the mountains of northwestern and western Mexico. They are typically not found in the southeastern United States.

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native ); palearctic (Native )

Other Geographic Terms: holarctic

Northern goshawks can be found in coniferous and deciduous forests. During their nesting period, they prefer mature forests consisting of a combination of old, tall trees with intermediate canopy coverage and small open areas within the forest for foraging. During the cold winter months they migrate to warmer areas, usually at lower elevations.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: taiga ; savanna or grassland ; chaparral ; forest ; mountains

There is little data on life span and survival of goshawks. The average survival, based upon small banding return samples, is 10.7 months. Maximum lifespan has also been neglected in research, but it is believed to be at least 11 years. Females have a higher rate of survival, mainly due to their larger body mass, which gives them an advantage during the winter months.

Range lifespan

Status: wild: 19.8 (high) years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 11 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 10.7 months.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 196 months.

Northern goshawks are the largest species of the genus Accipiter. Males generally weigh between 630 and 1100 grams, average 55 cm in length, and have a wingspan ranging from 98 to 104 centimeters. Females are slightly larger, weighing, on average, between 860 and 1360 grams, and having a wingspan of 105 to 115 centimeters and an average length of 61 cm.

All accipiters, including northern goshawks, have a distinctive white grouping of feathers which form a band above the eye (the superciliary). In goshawks this band is thick and more pronounced than in the other members of the species. The eye color of adult goshawks is red to reddish-brown, in juveniles eye color is bright yellow.

The colorings of adult male and female northern goshawks range from slate blue-gray to black. Their backs, wing coverts, and heads are usually dark, and their undersides are white with fine, gray, horizontal barring. Their tails are light gray with three or four dark bands.

A juvenile northern goshawk's coloring is quite different than that of the adult. Their backs, wing coverts, and heads are brown, and their undersides are white with vertical brown streaking.

Range mass: 631 to 1364 g.

Range length: 55 to 61 cm.

Range wingspan: 98 to 115 cm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: female larger

There are few natural predators of goshawks. Great horned owls, hawks and eagles, martens, eagle owls, and wolves, have been known to prey upon goshawks, particularly nestlings, during times of low food availability.

Northern goshawks are formidable birds and will attack trespassers in their nesting territories.

Known Predators:

While not endangered, northern goshawks are listed in Appendix II of the CITES agreement, which means that they can be traded between countries under certain circumstances, but would be threatened by uncontrolled trade. Northern goshawks are also protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

Timber harvesting is a major threat to northern goshawk populations. In recent years, several states such as Michigan, Washington and Idaho have listed northern goshawks as a Species of Concern and have increased conservation efforts focused on these birds.

US Migratory Bird Act: protected

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: appendix ii

State of Michigan List: special concern

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

When courting a mate, female goshawks will attract males in the area by either performing dramatic aerial displays and vocalizing, or by perching in the nesting area and vocalizing. Once a mate has been found, the two goshawks begin to construct or repair their nest. During this time, the pair will copulate many times a day, sometimes as many as 518 times per clutch.

Male and female goshawks typically maintain a life-long pair bond and only upon death will they seek out a new mate.

Mating System: monogamous

Northern goshawks breed once per year between early April and mid-June, with peak activity occurring at the end of April through May. A mating pair of northern goshawks begins to prepare their nest as early as two months before egg laying. Typically, the nest is located in an old growth forest, near the trunk of a medium to large tree and near openings in the forest such as roads, swamps, and meadows. Their nests are usually about one meter (39.4 inches) in diameter and one-half to one meter (19.7 to 39.4 inches) in height and are made of dead twigs, lined with leafy green twigs or bunches of conifer needles and pieces of bark.

The typical clutch size is two to four eggs, which are laid in two to three day intervals. The eggs are rough textured, bluish-white in color and measure 59x45 millimeters (2.3 x 1.8 inches) in size. The clutch begins to hatch within 28 to 38 days of laying. Incubation of the eggs is primarily the female's job, but occasionally the male will take her place to allow the female to hunt and eat. Nestlings stay at the nest until they are 34 to 35 days old, when they begin to move to nearby branches in the same tree. They may begin to fly when they are 35 to 46 days old. Juvenile fledglings may be fed by their parents until they are about 70 days old.

Breeding interval: Northern goshawks breed once yearly.

Breeding season: Breeding usually occurs between early April and mid-June, with peak activity occurring at the end of April through May.

Range eggs per season: 2 to 4.

Range time to hatching: 28 to 38 days.

Range fledging age: 34 to 35 days.

Average time to independence: 70 days.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 1 to 3 minutes.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 1 to 3 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; oviparous

Average eggs per season: 3.

Female goshawks do the majority of egg incubation, but occasionally males will incubate the eggs to allow the female to hunt and eat. After the clutch has hatched, the female will not leave the nesting area until the nestlings are 25 days old. During this time the male is the primary provider of food for the female and her nestlings. When the nestlings reach 25 days old, the female will leave them for periods of time to hunt with the male.

When nestling goshawks reach 35 to 42 days old, they begin to move to branches close to the nest. Soon after this, practice flights begin to occur. Often fledglings participate in "play" which is thought to allow them to practice hunting skills which will be needed throughout their lives.

Young goshawks tend to remain within 300 m of the nest until their flight feathers have fully hardened, at approximately 70 days. During this time fledglings still rely upon their parents for food. Full departure from the nest is often abrupt, though, and 95% of young goshawks become self reliant within 95 days of hatching.

Young goshawks reach sexual maturity as early as one year after hatching.

Parental Investment: no parental involvement; altricial ; pre-fertilization (Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Male, Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Male, Female, Protecting: Male, Female); pre-independence (Provisioning: Male, Female, Protecting: Male, Female)

Winter visitor.

Although closely related to the common Sharp-shinned and Cooper’s Hawks, the Northern Goshawk is encountered far less frequently. This is North America’s largest ‘bird hawk’ at 20-26 inches in length, and may be distinguished by its more familiar relatives by its larger size, grey-streaked breast, and dark cheek patch. Like most species of raptors, females are larger than males. The Northern Goshawk breeds in the Canadian sub-arctic, the northern tier of the United States, and at higher elevations in the Rocky Mountains south to central Mexico. This species may be found in its breeding range all year long, although some individuals move south into the mid-Atlantic, Ohio River valley, and Great Plains in winter. This species also inhabits northern Eurasia south the Mediterranean, Central Asia, and China. Northern Goshawks inhabit dense evergreen or mixed evergreen and deciduous forests. Like all ‘bird hawks,’ this species is equipped with the long tail and short, broad wings needed to hunt birds (on the ground, in trees, or in flight) from the air. Unlike most bird hawks, however, this species also takes Snowshoe Hare (Lepus americanus) in addition to avian prey. Large numbers of Northern Goshawks may wander far south of their normal range during winter in years when hare and grouse populations are low. With the aid of binoculars, Northern Goshawks may be seen perched in trees while scanning for prey. However, they are often more easily seen in the air while moving between perches or while actively hunting. As this species hunts by sight, it is only active during the day.

Although closely related to the common Sharp-shinned and Cooper’s Hawks, the Northern Goshawk is encountered far less frequently. This is North America’s largest ‘bird hawk’ at 20-26 inches in length, and may be distinguished by its more familiar relatives by its larger size, grey-streaked breast, and dark cheek patch. Like most species of raptors, females are larger than males. The Northern Goshawk breeds in the Canadian sub-arctic, the northern tier of the United States, and at higher elevations in the Rocky Mountains south to central Mexico. This species may be found in its breeding range all year long, although some individuals move south into the mid-Atlantic, Ohio River valley, and Great Plains in winter. This species also inhabits northern Eurasia south the Mediterranean, Central Asia, and China. Northern Goshawks inhabit dense evergreen or mixed evergreen and deciduous forests. Like all ‘bird hawks,’ this species is equipped with the long tail and short, broad wings needed to hunt birds (on the ground, in trees, or in flight) from the air. Unlike most bird hawks, however, this species also takes Snowshoe Hare (Lepus americanus) in addition to avian prey. Large numbers of Northern Goshawks may wander far south of their normal range during winter in years when hare and grouse populations are low. With the aid of binoculars, Northern Goshawks may be seen perched in trees while scanning for prey. However, they are often more easily seen in the air while moving between perches or while actively hunting. As this species hunts by sight, it is only active during the day.

The northern goshawk opportunistically feeds on a wide diversity of prey items that varies by region, season, and availability. Though the list of potential prey species is extensive, a few taxa are particularly prevalent in most diets [48]. Diet options may be narrower in northerly latitudes, where fewer prey species are available, than in lower latitudes [40,43].

Prey species prevalent in the diet of northern goshawks throughout their range [48] Mammals Tree squirrels Abert's squirrel (Sciurus aberti), eastern gray squirrel (S. carolinensis), Douglas's squirrel (Tamiasciurus douglasii), red squirrel (T. hudsonicus), northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus)Ground squirrels

Belding's ground squirrel (Spermophilus beldingi), golden-mantled ground squirrel (S. lateralis), Richardson's ground squirrel (S. richardsonii), Townsend's ground squirrel (S. townsendii) Lagomorphs cottontails (Sylvilagus spp.), jackrabbits (Lepus spp.), snowshoe hare Birds Phasianidae dusky grouse (Dendragapus obscurus), ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus), spruce grouse (Falcipennis canadensis) Corvidae American crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos), blue jay (Cyanocitta cristata), Steller's jay (C. stelleri), gray jay (Perisoreus canadensis), Picidae American three-toed woodpecker (Picoides dorsalis), black-backed woodpecker (P. arcticus), hairy woodpecker (P. villosus), northern flicker (Colaptes auratus), pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus),Williamson's sapsucker (Sphyrapicus thyroideus) Turdidae American robin (Turdus migratorius)Regional diet summaries are available from the Great Lakes [7,43], South Dakota [47], the central Rocky Mountains [26], and eastern Oregon [17].

Prey habitat and availability: Managing for prey species is a major component of habitat recommendations for the northern goshawk (e.g., see [40]). Northern goshawk populations may experience reduced fitness and reproduction, greater interspecific competition for food, and greater susceptibility to predators when food resources are limited [26]. Several reviews emphasize the importance of both prey abundance and availability when determining suitable northern goshawk habitat. In other words, prey need to be both present and huntable, with availability determined by stand structure [24,26].

For information on habitat preferences of northern goshawk prey species, see the following reviews from the Southwest [10,40,53] and central Rocky Mountains [26] or FEIS reviews for the following species: Abert's squirrel, Townsend's ground squirrel, eastern cottontail, black-tailed jackrabbit, snowshoe hare, ruffed grouse, gray jay, and black-backed woodpecker.

A review of the effects of fire on raptor populations suggests that direct mortality from fire is rare [30]. Adult northern goshawks are highly mobile and consequently are probably able to flee an approaching fire. Mortality from fire is most likely to occur during the breeding season when nestlings are unable to flee an approaching fire [30]. One wildlife biologist in western Montana thought a high-severity wildfire in August might have killed 2 northern goshawk nestlings observed 2 weeks prior to the fire [31].

Fire in the spring and summer may disrupt the breeding of northern goshawks.

All About Birds provides a distributional map of the northern goshawk.

States and provinces:

United States: AK, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DE, IA, ID, IL, IN, KS, KY, MA, MD, ME, MI, MN, MT, NC, ND, NE, NH, NJ, NM, NN, NV, NY, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, SD, TN, UT, VT, WA, WI, WV, WY

Canada: AB, BC, MB, NB, NF, NL, NS, NT, NU, ON, PE, QC, SK, YT (as of 2012 [34])

Mexico [48]

The lack of scientific information predicting the positive or negative consequences of fire management on the northern goshawk has legal, scientific, and social ramifications for land management agencies attempting to implement national fire programs [45]. Managers may not have many action options to protect northern goshawks in wildfire situations, but forest management activities (e.g., prescribed fire, thinning) aimed at fuels reduction and restoring historic stand structure are widespread in areas inhabited by northern goshawks. Many agencies suggest or require the designation of a buffer around nest trees when treatments occur, but there is some debate over the appropriate buffer size and the effectiveness of this approach, particularly because northern goshawks rely on a large landscape to meet life history needs [17,26,48]. One review critiques the buffer concept because the designation of buffers of a specific size around nests forces a predetermined restriction on all forest types—which may not be appropriate—gives the impression that management is not required beyond the buffer, and ignores the multiple scales at which northern goshawks use a landscape [17]. Reynolds and others [40] recommend avoiding or minimizing direct negative impacts on individual northern goshawks by restricting treatments or activities in the breeding season, particularly when females are incubating and/or young are immobile.

Because current FIRE REGIMES and forest conditions may fall outside of the range of historic variability in some parts of the range of northern goshawks, several sources suggest thinning and/or prescribed fire to restore historical stand characteristics and/or improve habitat for northern goshawks and their prey [13,14,26,35,40,53] and to make forests more resilient to high-severity wildfires [35]. In some cases, there is concern that mechanical and/or prescribed fire treatments aimed at converting dense forests to more open stands may result in a loss of habitat for species that use mature forest, like the northern goshawk [10,49]. On the other hand, some evidence suggests that avoiding treatment in areas to protect habitat for northern goshawks may have unintended negative consequences, particularly in the presence of high-severity fire. For example, in a mixed-conifer forest on the Plumas National Forest, northern California, managers left areas designated as protected northern goshawk habitat untreated during a fuels reduction treatment. When a wildfire burned through the region, fire severity in untreated areas was higher than in treated areas, resulting in significantly higher mortality of canopy trees (P less than 0.001) [21].

One review offers management recommendations for maintaining northern goshawk habitat in several Southwest FIRE REGIMES. In areas that experience infrequent fire, managers could create small openings that mimic wind events and other small-scale disturbances that historically maintained a diverse stand structure across the landscape. Such actions would provide a variety of interspersed stand structures that would support habitat for a wide range of prey species. In areas experiencing mixed-severity FIRE REGIMES, limiting large openings to small portions of a home range can help prevent fragmentation and ensure that enough mature forest habitat and canopy cover are available for both northern goshawks and their prey. In areas experiencing high-severity fire, northern goshawks may require relatively large home ranges (>9,900 acres (4,000 ha)) to ensure enough mature forest is available to provide adequate prey. Northern goshawks may also benefit from a range of seral to climax plant communities. Given the creation of large openings, rate of forest development, and tree longevity in areas experiencing high severity fire, the proportion of the landscape in various structural stages would likely vary. Management plans in these areas would require a scope of hundreds of years and landscape-level planning [23].

For information on combining management goals to include both habitat for the northern goshawk and fuels reduction projects that improve overall ecosystem function and resiliency to high-severity wildfire, see the following sources: [13,14,23,26,35,40,53]. For information regarding using fire and silvicultural techniques to restore fire-adapted ecosystems in the Southwest, see: [23,40,53].

Northern goshawk use of treated areas: Northern goshawks have been documented occurring and breeding in areas treated for fuels reduction and/or restoration, but their response to these treatments has not been well studied. The anecdotal information presented below suggests that northern goshawks may tolerate fuels reduction activities taking place in the breeding season, but use of treated areas is variable in subsequent years. It is not clear if non-use of a treated area is due to the physical disturbance during the breeding season or the resulting changes in local stand structure. It should also be noted that the lack of northern goshawk detections at particular nests does not mean territory abandonment; use of multiple nests in a territory is common and nests may not be detected by biologists (see Nest and nest side fidelity). The information presented here is largely anecdotal and limited in scope, and may not be representative of northern goshawk response to fuels reduction and restoration treatments throughout their range.

Two fuels reduction treatments occurred in northern goshawk territories in mixed ponderosa pine and Douglas-fir forests on the Bitterroot National Forest, western Montana. The prescriptions for both treatments left 30 to 40 acres (12-16 ha) untreated immediately surrounding known northern goshawk nests. The prescription also retained 80 to 100 feet²/acre basal area of canopy trees in the postfledging family area. Thinning in one territory containing 3 known nests occurred in 2006 and 2007. A nest successfully fledged young during the 2 years of treatments. No known nesting occurred in the territory in 2008 or 2011, but young were fledged from the territory in 2009, 2010, and 2012, with 2 different nests used. Thinning in a 2nd northern goshawk territory occurred after the northern goshawk breeding season in 2011. Northern goshawks successfully fledged young in 2011 prior to thinning, and in 2012 after thinning [31].

In southwestern Montana, the US Bureau of Land Management conducted a major thinning project to remove ladder fuels in Douglas-fir forest. Low-severity surface fires and pile burning were used to consume slash on the ground. Prior to treatment, the area consisted of a structurally diverse, multiaged stand with a large component of large, mature trees. The treatment resulted in a more "park-like" and open structure, though most of the mature trees were left standing. One female goshawk twice tolerated the activities associated with this project, continuing to incubate despite the presence of an active skid trail within 98 feet (30 m) of her nest the 1st year of treatment, and a burning slash pile within 66 feet (20 m) of her nest the 2nd year of treatment. In both instances, the female did not abandon incubation duties and young were successfully fledged. However, nest location shifted between the 2 years, with the pair building a new nest in a "leave" tree remaining after the thinning occurred. Northern goshawks were not detected nesting in the treated area again, though an adjacent, untreated territory was occasionally occupied [27].

One active northern goshawk nest was discovered during a selection-harvest fuels reduction treatment in 1993 in a mixed-conifer forest on the Bitterroot National Forest, western Montana. After this discovery, a small island of trees was left surrounding the nest, and approximately 100 feet²/acre basal area of canopy trees was left in the surrounding unit. The female continued incubating, and 2 young hatched while the treatments were conducted. Though the nest successfully fledged young that year, it was not used by northern goshawks in subsequent years, presumably because of the reduction in overstory canopy cover. The nest was used by great horned owls and Cooper's hawks after treatment [31].

In mixed-conifer forests on the Lolo National Forest, western Montana, northern goshawks were detected in treated (low-severity fires and selection harvest) and untreated "old growth" stands at frequencies similar to those found throughout the area [11]. One biologist observed northern goshawks nesting for 2 years within thinned lodgepole pine forests on the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest, southwestern Montana [27].

Because of their broad distribution, northern goshawks occur in plant communities that experience a wide range of FIRE REGIMES, including FIRE REGIMES characterized by low-severity, mixed-severity, or stand-replacement fire. Return intervals may be short to long. In the western United States, fire creates a landscape mosaic capable of supporting northern goshawk populations. Northern goshawks and their prey have historically had exposure and adapted to forest conditions maintained by a variety of FIRE REGIMES, including nonlethal surface, mixed-severity, mosaic, and stand-replacement fire [23]. However, several reviews discuss how FIRE REGIMES within the range of the northern goshawks have shifted away from historic patterns due to fire exclusion and other anthropogenic practices [10,12,23,30,32,40,51]. Changes in the frequency and severity of fire have resulted in shifts in forest composition and structure, which may impact northern goshawks and their prey [26]. Documented forest changes that may result from fire exclusion and other anthropogenic practices include reduced stand structural diversity [32], increased stand density [12,32,40,51], increased understory density [12,40], and changes in species composition [40,51]. Such forest structural and compositional changes may limit the mobility and hunting success of northern goshawks [19] and cause changes to prey populations and diversity [12,19,40]. In some cases, forest structural and compositional changes may increase the probability of high-severity fires [40,51], which would reduce the amount of mature forest on the landscape [10,40], eliminate nesting habitat, and create forest openings larger than what occurred historically [19]. Though these forest changes are generally discussed in the literature as reducing habitat for northern goshawks, it is possible that forest changes in some areas may improve habitat for northern goshawks.

One review discusses how several FIRE REGIMES typical of Southwestern forests may have influenced northern goshawk populations in the region. Nonlethal, low-severity surface fires in ponderosa pine forests would "clean" the forest, providing suitable foraging habitat and open canopies that enabled northern goshawks to successfully access prey. Large trees would eventually die from lightning, disease, or insects and provide snags or coarse woody debris, habitat features important to northern goshawk prey. These fires would gradually consume downed logs, but not before the logs contributed to habitat for prey species and added organic matter to the soil. The small openings left would allow for the regeneration of new trees. Mixed-severity FIRE REGIMES in relatively moist coniferous forests would create larger openings (>4 acres (2 ha)), greater amounts of coarse woody debris, and multiple canopy layers compared to less severe fires. These fires could create openings of all sizes, leading to a mosaic of forest structural conditions across the landscape. Large openings would likely not provide ideal northern goshawk foraging habitat, but the edges of these openings might be used. Large forest openings may have been historically important for maintaining seral quaking aspen stands, an important component of many northern goshawk home ranges in this region. Forests maintained by high-severity fires may have limited value as northern goshawk habitat because they result in large (>24 acres (10 ha)) openings and/or an even-aged structure across a large landscape [23]. For management recommendations pertaining to these and other FIRE REGIMES throughout the range of the northern goshawk, see Fire Management Considerations.

The Fire Regime Table summarizes characteristics of FIRE REGIMES for vegetation communities in which northern goshawks may occur. Follow the links in the table to documents that provide more detailed information on these FIRE REGIMES. Northern goshawks also occur in geographic areas not covered by the Fire Regime Table, including a variety of boreal plant communities in Alaska and Canada, as well as forested plant communities in Mexico. Find further fire regime information for the plant communities in which this species may occur by entering the species name in the FEIS home page under "Find FIRE REGIMES".

FEIS also provides reviews of many of the prey species important to the life history and habitat use of northern goshawks. See FEIS reviews for additional information—including information on FIRE REGIMES and fire effects on species including: Abert's squirrel, Townsend's ground squirrel, eastern cottontail, black-tailed jackrabbit, snowshoe hare, ruffed grouse, gray jay, and black-backed woodpecker.

As of this writing (2012), there was little documentation of the indirect effects of fire on northern goshawk individuals or populations. Presumably, the occurrence, extent, and severity of fire could have major impacts on small- and large-scale forest structure which in turn may affect the suitability of an area for life history activities such as breeding and foraging. Effects may be positive or negative and could vary regionally.

A review of the effects of fire on raptor populations suggests that the most significant effect is the modification and/or destruction of habitat. Habitat losses can include small-scale losses like an individual nest tree or a roost site or large-scale losses like the elimination of a foraging area [30]. However, fire may also modify the landscape in ways that improve habitat for northern goshawks (e.g., the creation of a mosaic of stand structures).

Northern goshawk populations have long been exposed to wildfire as a natural disturbance process [23], and some sources suggest that northern goshawks can adjust to changing environmental conditions [10,26]. Northern goshawks exhibit some life history characteristics that make them adaptable to landscape disturbances such as fire. They maintain a large breeding territory that contains several nest sites, so if one nest site is altered or destroyed, they may have other nearby options (see Nest and nest site fidelity). Though most sources report the use of mature forests for nesting, northern goshawks occasionally nest in areas with few trees or in small forest patches [10]. Northern goshawks use a variety of forest structures when foraging [23,26], and though they often rely heavily on mature forest while foraging [3,10,17], they also forage in young forests, edges, and openings [10,17,43] (see Foraging habitat).

Indirect fire effects on nesting: Fire may consume northern goshawk nests, nest stands, and/or breeding territories. A review suggests that stand-replacement wildfire could reduce the suitability of an area for northern goshawk nesting and create forest openings larger than what occurred historically [19].

Two biologists working with northern goshawks in Montana provided observations of fire effects on northern goshawk nesting. It should be noted that these observations are anecdotal and may not be representative of northern goshawk response to fire throughout its range.

One biologist studied northern goshawk nest and territory occupancy over many years in lodgepole pine forests on the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest, southwestern Montana. A stand-replacing wildfire in 2007 burned 2 historical northern goshawk territories, though the territories were not occupied in the years prior to the fire. The fire resulted in a reduction of suitable nesting habitat, leaving a patchy distribution of unburned forest amidst largely open meadows. Three and 4 years after the fire, northern goshawks nested in an unburned patch of forest midway between the historical territories. These observations show that northern goshawks can shift to remaining suitable nesting stands even when stand-replacing fire has consumed most of the vegetation in an area [27].

A 2nd biologist observed that high-severity wildfires occurring in mixed-conifer forests on the Bitterroot National Forest, western Montana, in August of 2000 consumed 2 known northern goshawk territories and several nests, 1 of which was active 2 weeks prior to the fire. The young in this nest were presumed dead, though it is possible they were able to fly well enough to escape the area. The landscapes surrounding both territories experienced extensive stand-replacement fire, and local biologists described the territories as unsuitable for northern goshawk nesting in the years following fire [31].

Low-severity fires may result in nest abandonment, though not always immediately. In one area on the Bitterroot National Forest, western Montana, a low-severity fire in August of 2000 consumed most of the forest understory but left the overstory intact. The fire killed most of the trees in the sapling and intermediate layers as well as many Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii) and subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa) in the overstory via bole scorch, but almost all of the Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) survived. Douglas-fir beetles (Dendroctonus pseudotsugae) began causing overstory canopy mortality by 2002, with many trees exhibiting red needles by the summer of 2003. Northern goshawks nested in the stand prior to fire and continued to nest and successfully fledge young in the stand for several years after the fire, though biologists found a new and different active nest each year from 2001 to 2004. The nesting area was eventually abandoned; none of the 4 known nests were active in 2005, 2006, or 2007, though it is possible that other nests were constructed in the area and not found. Local biologists suspected the area was abandoned because canopy closure decreased as overstory mortality increased [31].

In another area on the Bitterroot National Forest, western Montana, burned by low-severity fire in 2000, a northern goshawk nest tree was killed, but much of the surrounding nest stand was not killed. The nest was abandoned and eventually fell out of the tree. In other instances where nest stands were burned by low-severity fire in 2000, the canopies around the nests gradually thinned out as surrounding trees died, and the nests were not used again. However, in all instances, biologists were unable to determine if northern goshawks left the area completely or if they shifted to unlocated nests within the territory [31].

Indirect fire effects on foraging: The effect of fire on foraging habitat likely varies with fire severity and extent across a landscape. For example, an extensive, high-severity fire that results in major canopy and understory mortality may result in poor habitat for some prey species for many years after fire. The dense regeneration that may follow stand-replacing fire in some forest types (e.g., lodgepole pine) may inhibit the ability of northern goshawks to detect prey. A fire that creates a mosaic of forest structures and openings may offer northern goshawks a variety of foraging opportunities and provide habitat for a wide range of prey species. Since open understories may enhance the detection of prey items, low-severity fires that consume the understory but maintain a live overstory may create foraging opportunities [3,40,43]. The impact of fire on foraging habitat may be greater in the breeding season, when northern goshawks are tied to a nest and breeding territory, than in the winter, when individuals are more flexible in how far and where they travel to forage and use a wider range of habitats (see Foraging habitat).

Northern goshawk occurrence in burned areas: To date (2012), the documentation of northern goshawks occurring in burned areas is rare and largely incidental, making generalizations difficult. Between 1 and 3 years after a low- to moderate-severity prescribed fire in northern Arizona, one northern goshawk was detected during winter point counts [38,39]. One northern goshawk was detected on the ecotone between burned and unburned lodgepole pine forest 8 years after a high-severity wildfire in north-central Colorado [44]. In mixed-conifer forests on the Lolo National Forest, western Montana, one northern goshawk responded to a playback call in the breeding season in an area treated approximately 10 years previously by a low-severity "ecosystem burn" aimed at retaining the stand's old growth characteristics [11]. In central Alaska, a northern goshawk was killed by an American marten in boreal forest burned approximately 25 years previously. The forest was in a midsuccessional stage of dense tree regeneration, though some severely burned lowlands were in an earlier shrub-sapling stage. Mature forest in the area was primarily black spruce (Picea mariana) and tamarack (Larix laricina) [36]. Three years after mixed-severity wildfires in a ponderosa pine forest in Arizona, researchers detected 2 northern goshawks in an unburned area adjacent to burned forest while conducting point counts in the nonbreeding season. Northern goshawks were not detected in any area (unburned, moderately burned, severely burned) in the breeding season or in severely or moderately burned forest in the nonbreeding season [8].

Description: The northern goshawk is a large forest hawk with long, broad wings and a long, rounded tail. Females average 24 inches (61 cm) in length, 41 to 45 inches (105-115 cm) in wingspan, and 30 to 45 ounces (860-1,264 g) in mass, while the smaller males average 22 inches (55 cm) in length, 39 to 41 inches (98-104 cm) in wingspan, and 22 to 39 ounces (631-1,099 g) in mass [48].

Adult northern goshawks are brown-gray to slate-gray on top. The head has a black cap and a pronounced white superciliary line. Underparts are light gray with some black streaking. The tail is dark gray above with 3 to 5 inconspicuous broad, dark bands, and sometimes a thin white terminal band. Juveniles are generally brown on top and have brown streaking on the chest [48].

Adult (left) and juvenile (right) northern goshawks. Photos by Jack Kirkley.Life span: Based on band recoveries at trapping sites, the maximum life span of wild northern goshawks is at least 11 years [48]. One review reports a captive northern goshawk living 19 years [26].

Age at first breeding: Northern goshawks may breed as subadults (1-2 years old), young adults (2-3 years old), or adults (≥3 years old). Females are more likely than males to breed at a young age [48].

Home range: In North America, home range in the breeding season ranges from 1,400 to 8,600 acres (570-3,500 ha) [48]. Home range size varies depending on sex [26,48], season [48], local prey availability, climate [7], and habitat characteristics [7,26,48]. The male's home range is generally larger than the female's. Within a home range, individuals often have core-use areas that include the nest and primary foraging areas. Outside of a nesting area, the home range of a breeding pair may not be defended and may overlap with the home range of adjacent pairs. The shape of a home range may vary from circular to linear or may be discontinuous, depending on local habitat characteristics [48].

Nesting phenology: Northern goshawk pairs occupy nesting areas from February to early April. Some pairs may remain in their nesting areas year-round. Nest construction may begin as soon as individuals return to their territories. Eggs are laid anywhere from mid-April to early May. Cold, wet springs may delay incubation. Incubation varies from 28 to 37 days. Nestlings move from nests to nearby branches when they are around 34 to 35 days of age. Their first flight from the nest tree ranges from 35 to 36 days for males and 40 to 42 days for females. They reach independence approximately 70 days from hatching. Most fledglings disperse from the nest area between 65 and 90 days after hatching, with females dispersing later than males [48].

Clutch size: Northern goshawks usually produce one clutch per year. Clutch size is usually 2 to 4, but occasionally 1 or 5 eggs. Because northern goshawk chicks hatch asynchronously, older, larger nestlings may attack smaller, younger nestlings [48].

Northern goshawk female with young.Nest success and productivity: Northern goshawk nest success and productivity vary and may be limited by prey availability [6,46,48], weather [26,48], predation [7,26], disease [26], habitat features [24], and disturbance from timber harvest or other human activities [26,48].

In North America, nest success usually ranges from 80% to 94%, with most successful nests producing an average of 2.0 to 2.8 fledglings. Unsuccessful nests usually fail early in the breeding season, before or soon after laying. Weather, particularly cold temperatures in the spring and exposure to low temperatures and rain, may cause egg and chick mortality. Once chicks reach 3 weeks of age, nests rarely fail. Productivity may differ between years in the same study area and among landscapes within a limited geographic area. The availability of prey strongly affects nest occupancy and productivity. The age of the female may also affect productivity; pairs with a younger female may produce fewer fledglings than pairs with an older female. If food resources are low, siblicide and cannibalism may occur [48].

Nest description: The northern goshawk constructs a nest of thin sticks, forming a bowl lined with tree bark and greenery. Nests are usually placed on large horizontal limbs against the trunk, or occasionally on large limbs away from the bole. A variety of tree species is used for nesting [48].

Northern goshawk nest in western Montana.Nest site: Northern goshawks build nests in both deciduous and coniferous trees. They typically use the largest tree in a nest stand. Nest height varies by tree species and regional tree characteristics. The size and structure of a nest tree may be more important than species. Northern goshawks occasionally build nests on dwarf mistletoe (Arceuthobium spp.) clumps and rarely in dead trees [48]. Several reviews provide lists of specific tree species used by northern goshawks for nesting throughout their range [48] and in the Great Lakes region [7] and central Rocky Mountains [26].

Nest and nest site fidelity: Northern goshawks may use the same nest for consecutive years, but they usually alternate between 2 or more nests within a nest area. They may maintain as many as 8 alternate nests within a nest area. It is thought that most nest sites are occupied from 1 to 3 years, though some may be occupied much longer. Though the importance of alternate nest maintenance is not completely understood, it is hypothesized that nest switching reduces exposure to diseases and parasites. This behavior complicates the determination of nest-site fidelity because it is difficult for biologists to locate all alternative nests [48]. A synthesis of 5 studies correlating nest occupancy with habitat features found a consistently positive relationship between closed-canopy forests with large trees and northern goshawk nest occupancy. Occupancy rates were reduced by removing forest cover in the home range, which thereby resulted in reduced productivity because there were fewer active breeding territories [24].

Dispersal: Natal dispersal of the northern goshawk had not been well studied as of this writing (2012). One review notes that very few (24 of 452) fledglings in an Arizona study were recruited into the local breeding population, and mean natal dispersal distance was 9.1 (SD 5.1) miles (14.7 (SD 8.2) km) (range 2.1-22.6 miles (3.4-36.3 km)) [26]

Mate fidelity: Northern goshawks may show high mate fidelity. A study from northern California found that over 9 years, 72% of the adults located in subsequent years (18 of 25 instances) retained the mate from the previous year [18].

Density: Northern goshawk populations occur at low densities compared to many bird species [43]. One review reports that regular territory dispersion is a consistent characteristic of northern goshawk populations that likely results from territorial behavior. In North America, mean nearest neighbor distances range from 1.9 to 3.5 miles (3.0-5.6 km) [26], and density estimates range from less than 1 to 11 pairs per 100 km². Densities in the range of 10 to 11 occupied nests per 100 km² were reported for 3 study areas in Arizona, California, and the Yukon. However, nest density across a landscape is difficult to determine and often based on either assumed censuses of breeding pairs or the distribution of nearest neighbor distances. Because most searches for nests are conducted in what is predetermined to be "suitable" habitat, reported densities may not accurately reflect the number of territories per unit area. Surveys may also be incomplete or inaccurate [26].

Migration: The northern goshawk is considered a partial migrant. Some individuals, particularly those that inhabit northern latitudes, may migrate long distances. Other individuals make short winter movements to lower elevations and/or more open plant communities. Food availability in the winter may influence the degree to which individuals or populations migrate [40,48].

Predation and mortality: Northern goshawks are vulnerable to predation from red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis), short-eared owls (Asio flammeus), great horned owls (Bubo virginianus), American martens (Martes americana) [48], fishers (M. pennanti) [7], wolverines (Gulo gulo) [48], coyotes (Canis latrans), bobcats (Lynx rufus), and northern raccoons (Procyon lotor) [40]. It is likely that other mammals prey on nestlings and/or adults [48]. In the Great Lakes region, great horned owls were the most common nest predator [7]. Other potential sources of northern goshawk mortality include starvation, disease, shooting, trapping, poisoning, and collisions with vehicles [48].

Interspecific competition: Reduction and fragmentation of mature forest habitat may favor early-successional competitors such as red-tailed hawks and great horned owls and reduce occupancy of an area by northern goshawks [26]. One study from California found great horned owls, long-eared owls (Asio otus), spotted owls (Strix occidentalis), red-tailed hawks, and Cooper's hawks (Accipiter cooperii) occupying traditional northern goshawk nests or nest stands, but the territories were usually not abandoned entirely by northern goshawks. In 3 instances, however, northern goshawks moved out of their traditional nest stand after it was occupied by spotted owls [51].

Great gray owls (Strix nebulosa) using a nest formerly used by northern goshawks.Population dynamics: Factors limiting northern goshawk populations may include food availability [10,26,40,48], availability of nest sites [40], and territoriality [26]. Food availability is more of an issue in northern latitudes, where northern goshawks are more dependent on populations of few species (e.g., snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus)). There is less evidence of population fluctuations in response to food in lower latitudes, where a greater variety of prey species are available [40,43]. See Population status for more information on how stand and landscape characteristics may influence northern goshawk populations.

Federal legal status: The Queen Charlotte subspecies of the northern goshawk is listed as Threatened [50].

Other status: Information on state- and province-level protection status of animals in the United States and Canada is available at NatureServe, though recent changes in status may not be included.

Other management information:

Population status: Trends in northern goshawk populations are difficult to assess for several reasons. Northern goshawks are secretive and consequently difficult to survey. Many studies have small sample sizes and are temporally and/or spatially limited in scope. Methodology in some studies may be biased and methods, analyses, and interpretation vary between studies [43]. Attempts to assess the status of northern goshawk populations have not found strong evidence supporting population declines, though most studies were not designed to detect population changes [10,26]. Populations may also vary regionally; some managers in New England suspect northern goshawk populations may be increasing due to widespread reforestation in the region, but they lack definitive data to support this hypothesis [15].

Northern goshawks exhibit some life history characteristics that facilitate adaptation to landscape change. They maintain a large breeding territory that contains several nest sites, so if one nest site is altered or destroyed, they may have other nearby options (see Nest and nest site fidelity). Though most sources report the use of mature forests for nesting, northern goshawks occasionally nest in areas with few trees or in small forest patches [10]. Similarly, they forage over large areas, using open areas and a variety of forest structures (see Foraging habitat). Several sources suggest that they adjust to changing environmental conditions [10,26]. Northern goshawks also show plasticity in migration strategy, allowing individuals to seasonally avoid areas where habitat has been degraded [26].

Landscape management decisions can influence the success of individuals or pairs of northern goshawks and northern goshawk populations. One review asserts that the primary threat to northern goshawk populations is the modification of forest habitats by management and natural disturbances [10]. Though it is difficult to assess the population status of northern goshawks, managers have raised concerns over destruction and/or modification of northern goshawk habitat via natural and anthropogenic disturbances. Natural disturbances that may impact northern goshawk habitat include severe wildfires [10], insect outbreaks [17], and drought [40]. Diseases, parasites, exposure, and predation tend to impact individuals rather than populations [10]. Potential anthropogenic threats to northern goshawk habitat include silvicultural treatments that result in forest fragmentation, creation of even-aged and/or monotypic stands, potential increase in acreage of young age classes, and loss of tree species diversity [43]. Other anthropogenic threats to northern goshawk populations include fire suppression activities [17,40], livestock grazing, exposure to toxins and chemicals [40], and timber harvest [10,17,26,40].

Timber harvest: The impact of timber harvest on northern goshawks is much debated in the literature, and centers mostly on the loss of mature forest. Though many believe that extensive habitat modification due to timber harvest is detrimental to northern goshawk populations, a lack of research across a gradient of tree-harvest intensities precludes a clear demonstration of negative effects [10]. Furthermore, few studies have investigated northern goshawk habitats in forests not managed for timber harvest [26].

Forest management for timber extraction can directly impact the structure, function and quality of both nesting and foraging habitat by removing nests and nest trees, modifying or removing entire nest stands, and removing the canopy and mature trees, snags, and downed wood that support prey populations [26]. The loss of important habitat features could impact both the ability of northern goshawks to access prey items (e.g., inability to hunt in areas of dense tree regeneration) and limit prey populations [40]. Reduction and fragmentation of habitat may also favor early-successional competitors and predators such as red-tailed hawks and great horned owls [26]. Indirect impacts of timber harvest on nesting may vary; breeding densities may be lowered or individuals may move to adjacent, undisturbed areas [48]. The threshold at which landscape-altering projects render an area unsuitable to northern goshawks likely varies spatially and/or temporally [26]. However, one source suggests that in some cases (e.g., the inland Pacific Northwest), nonharvest forestry may be just as detrimental to northern goshawk nesting habitat as aggressive, maximum-yield forestry [17].

The following sources provide information on reducing potential negative impacts of timber harvest on northern goshawk individuals and populations: [9,48].

Management actions to benefit northern goshawks: Managers and researchers offer many suggestions for managing forested landscapes to benefit northern goshawk populations. These recommendations include stand-level treatments like maintaining large trees, snags, and large downed logs [40] and larger-scale suggestions such as maintaining and enhancing mature forests [10,15,26,40], limiting forest fragmentation [26], and maintaining a mosaic of structural stages [17,26,40]. Several authors suggest managing at multiple scales [17,26,40]. However, because stand and landscape characteristics, as well as management objectives, vary throughout the range of northern goshawks, no management plan or prescription can encompass the variety of conditions northern goshawks might encounter [40]. For example, in the western United States, 78% of the habitat occupied by nesting northern goshawks occurs on federally managed lands, while in the eastern United States, most forested areas are privately owned [10]. Several sources offer regional recommendations for managing forests for northern goshawk habitat, including recommendations for New England [15], the Great Lakes [7], the Black Hills region of South Dakota [47], the central Rocky Mountains [26], west-central Montana [12], the western United States [24], the southwestern United States [40], the inland Pacific Northwest [17], and California [42]. Several sources offer recommendations for silvicultural and other physical treatments (e.g., forest restoration, understory thinning, prescribed fire) to increase the availability of mature forest and/or restore historical stand conditions to improve habitat for northern goshawks and their prey [10,26,32,40,48]. See Fire Management Considerations for more information on this topic.HABITAT:

Northern goshawk habitat includes a variety of forest types and stand structures, depending on geographic location and life history activities. The northern goshawk's large home ranges and ability to move great distances mean that it may encounter a variety of habitats over a short period. In addition to nesting habitat, northern goshawks need foraging habitat in both the breeding and nonbreeding seasons and in postfledging areas where young learn to hunt but are protected from predators [43]. Habitat selection may be shaped by landscape structure and pattern and/or occupancy by other raptors [43]. In general, as the scale of analysis increases (i.e., from stand to landscape), northern goshawks use more diverse habitats and show less preference for specific habitat features [3,10,17,43]. Northern goshawks appear to use a wider range of habitats during the nonbreeding season than the breeding season [3].

In general, northern goshawks appear to prefer relatively dense forests [24,25,47] with large trees [3,24] and relatively high canopy closures [3,24,25,47]. A review noted that 9 of 12 radio telemetry studies from the western United States found northern goshawks selected stands with higher canopy closures, larger trees, and more large trees than found in random stands. But northern goshawks still used stands with a wide range of structural conditions [24]. The use of forests with relatively large trees and high canopy closures may be related to increased protection from predators, increased food availability, limited exposure to cold temperatures and precipitation early in the breeding season, limited exposure to high temperatures in the summer nestling period, high mobility due to a lack of understory structure, and less competition from other raptor species that inhabit more open habitats [3].

The relatively large body size and wingspan of the northern goshawks limit its use of young, dense forests where there is insufficient space in and below the canopy to facilitate flight and capture of prey. There are also few suitably large trees for nesting in young, dense forests [40].

Breeding habitat: Northern goshawk habitat use may be most selective during the breeding season, mostly due to strong preferences for nest placement [43,48].

Nest stand: Forest stands containing nests are often small, ranging from approximately 24 to 247 acres (10-100 ha) [48]. Tree species composition is highly variable among nest sites both within a region and a across the range of the northern goshawk [40]. Northern goshawks nests are often found in mature or late-successional forests [3,15,17,43,48] with high canopy closures [9,17,43,47,48] and large trees [43,48] but relatively open understories [26,43,48]. However, due to frequent bias in northern goshawk nest detection methods, the selection of mature forest over other forest successional stages has been demonstrated in only a few studies [43].

Northern goshawks nested in this conifer forest in western Montana.

Though northern goshawks are most often documented nesting in late-successional forests, they sometimes nest in younger, more open forests. For example, in dry areas of the West such as the Great Basin, northern goshawks nested in high-elevation shrubsteppe habitats supporting small, highly fragmented stands of quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) [52]. In a conifer plantation in western Washington, 3 northern goshawk pairs nested in younger, denser stands than previously reported for the region; nest sites were composed of 40- to 54-year-old, second-growth conifer stands with high live tree and snag densities [9].

Northern goshawk nest sites are often located near water [43,47,52], though some studies have shown no association between nest sites and water [26,43] and the presence of water is not considered a habitat requirement [48]. The function of open water during nesting is unknown [43].

Nest sites often are located close to forest openings or other open areas [12,15,26,43,47], which may increase nest access, serve as travel corridors, support open-habitat prey species, or reduce flight barriers to fledglings [48]. However, one study from west-central Montana noted that the number of young fledged per nest was negatively correlated with the size of the nonforested openings near the nest (P≤0.05) [12].

Slope and aspect may influence microclimate conditions important to northern goshawk nesting. Northern goshawk nests are often located at the base of moderate slopes [48] and tend to be on gentle rather than steep terrain [15]. However, there may be no relationship between nesting and slope in areas with low topographic relief, like the Great Lakes region [7]. One study from west-central Montana found that 82.6% of occupied nests were located on north slopes [12]. Preferred aspects may vary regionally; one review noted that in southern parts of the range, northern goshawks nest areas typically had northerly aspects, while nest areas in interior Alaska had southerly aspects [26].

Postfledging family areas: A postfledging area represents the area of concentrated use for a northern goshawk family from the time the young leave the nest until they are no longer dependent on the adults for food. Northern goshawks typically defend this area as a territory. Postfledging family areas provide hiding cover and prey for fledglings to develop hunting skills. They typically contain patches of dense trees, developed herbaceous and/or shrubby understories, and habitat attributes that support prey, such as snags, downed logs, and small openings. Postfledging family areas range in size from 300 to 600 acres (120-240 ha) [40].

Wintering habitat: Northern goshawk breeding habitat has been studied much more intensively than nonbreeding habitat. In general, northern goshawks use a wider range of habitats during the nonbreeding season than during the breeding season [48]. One review reports that northern goshawks in northern Arizona may select winter foraging sites based on forest structure rather than prey abundance, similar to selection in the breeding season [26] (see Foraging habitat). In some regions, northern goshawks appear to remain near breeding areas throughout the year [3,7,43], though there is considerable annual variation and variation between sexes in nonbreeding habitat use [3]. In at least some landscapes, northern goshawks forage in late-successional forest habitats throughout the year [3,24]. However, some northern goshawks move to low-elevation, open plant communities (e.g., woodlands) in the winter [3,24].

Foraging habitat: Northern goshawks forage by ambush and perching in vegetation to scan for prey items. They occasionally hunt by flying rapidly along forest edges and across openings [26]. Ideal foraging habitat includes space under the canopy to allow for flight, abundant trees perches, and available prey [53]. Preferred perches while hunting are low (usually <3 feet (1 m)), bent-over trees or saplings. Plucking perches where northern goshawks consume prey are usually located in dense vegetation below the main forest canopy and are often upslope and fairly close to the nest in the breeding season [48].

Northern goshawks forage over large areas and encounter a variety of forest structures [23,26] and plant communities [48] when foraging. In the breeding season, a foraging area may encompass 5,400 acres (2,200 ha) surrounding the postfledging family area [40]. Northern goshawks may rely heavily on mature forest while foraging [3,10,17] but may also forage in younger forests, edges, and openings [10,17,26,43]. An open understory may enhance the detection of potential prey [3,40,43].

Prey abundance may be an important feature of foraging habitat, but several sources stress the importance of prey availability [3,5,22,26,40,53], which is often linked to vegetative structure that allows northern goshawks to hunt successfully [3]. For example, over 2 breeding seasons in ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) forests in northern Arizona, 20 adult northern goshawks did not select foraging sites based on prey abundance; abundance of some prey was lower in selected sites than what was generally available. Northern goshawks instead selected foraging sites that had higher canopy closure (P=0.006), greater tree density (P=0.001), and greater density of trees >16.0 inches (40.6 cm) DBH (P<0.0005) than what was generally available. The authors concluded that above a minimal prey threshold, northern goshawks may select sites with favorable structure over those with abundant prey. However, they also suggested that their results only apply to foraging habitat selection within an established home range. Prey abundance may be an important factor when northern goshawks initially establish a home range [5].

In the Great Lakes region, male northern goshawks primarily foraged in mature upland conifer and upland deciduous stands, but other stand types were used and may be important to prey production [7]. In lodgepole pine (P. contorta) and quaking aspen forest in south-central Wyoming, the kill sites of male northern goshawks in the breeding season were more related to stand structure and aspect than prey abundance. Males returned most often to sites with more mature forests (P=0.0), gentler slopes (P=0.011), lower ground cover of woody plants (P=0.023), and greater densities of trees (P<0.089) and conifers (P<0.14) ≥9 inches (23 cm) but ≤15 inches (38 cm) DBH. Average canopy closure at kill sites was 52.8%. Kill sites were often associated with small openings; average distance to the nearest open area was 152.2 feet (46.4 m). The author noted that several prey species were often associated with forest edges. The results of this study suggest that the high density of large trees allowed northern goshawks to approach prey unseen, while the low density of understory vegetation allowed northern goshawks to see potential prey items. At the landscape scale, male northern goshawks intensively used large areas of conifer forests interspersed with small openings in proximity to nests. They used a variety of habitats, from narrow patches of quaking aspen in drainages surrounded by sagebrush (Artemisia) and grassland to areas dominated by conifer forests [22].

Roosting habitat: Northern goshawks roost alone in the tree canopy and may use several sites for roosting. In the early nesting phase, female northern goshawks roost on the nest while brooding young [48]. In California, roost tree species and roosting stand characteristics varied by season, which the authors hypothesized was in response to changes in prey abundance and availability [42].

Landscape features: Northern goshawks use large landscapes for many life history activities, though it is difficult to make broad generalizations about the importance of landscape features to northern goshawk populations. Studies and reviews highlight the importance of landscape features such as the presence of large areas of mature forest [10,15,26,40], a mosaic of forest structural stages [17,25,26,40], limited forest fragmentation [26,51], and large patch sizes [9,43,51].

The scientific name of northern goshawk is Accipiter gentilis Linnaeus (Accipitridae) [1,2]. Subspecies recognized by the American Ornithologists' Union (5th edition) [1] include:

Accipiter gentilis atricapillus (Wilson), northern goshawk

Accipiter gentilis laingi (Taverner), Queen Charlotte goshawk

Some scientists recognize an additional subspecies, Accipiter gentilis apache Van Rossem, as inhabiting parts of the southwestern United States and Mexico, though this subspecies is not recognized by the American Ornithologists' Union or the US Fish and Wildlife Service [10,26,48].

El ferre o azorNOA (Accipiter gentilis) ye una especie d'ave accipitriforme de la familia Accipitridae.[2] N'España, el so estáu de caltenimientu defínese como una especie d'esmolición menor (LC).[3]

Ye de tamañu medianu (mide ente 48 y 58 cm; abondo asemeyáu a un buzacu) y la forma del so cuerpu aseméyase a un gran ferre palomberu (Falco peregrinus), anque la especie ta venceyada coles águiles. El so valumbu ye d'ente 100 y 120 cm, y como en toles aves rapaces, el machu ye de menor tamañu que la fema.[4] Los mozos presenten tonos claros: acoloratáu enriba y mariellu con grandes llurdios de color pardu escuru na zona de baxo. Los adultos tienen una coloración parda ceniza, de tonos buxos y coritos na rexón cimera, ente que les partes inferiores son ablancazaes horizontalmente barraes n'escuru. Tienen dos enllordies blanques percima de los sos grandes güeyos y l'iris ye mariellu o naranxa; estes postreres carauterístiques son dalgunes de les más evidentes diferencies faciales colos ferres, qu'escarecen d'estos llurdios y que los sos iris son escuros.

El azor ye una ave especializada na caza d'ecosistemes arbóreos; les sos ales resulten curties pal so tamañu, y tienen los estremos arrondaos; coles mesmes, la so cola ye proporcionalmente llarga, y barrada con 4 o 5 franxes escures. Estes carauterístiques déxen-y una gran movilidá y capacidá de maniobra nun ambiente con muncha vexetación, y les sos ales curties torguen que choque escontra la foresta del monte de mou que ye a volar ensin problemes nun ambiente trupu. Estes carauterístiques cinexétiques diéron-y el so valor dende l'antigüedá como ave predileuta en cetrería pa cazar nel monte.[5]

El azor (lo mesmo que les águiles) nun mata a les sos preses esnucándoles col picu como faen los ferres palomberos sinón que fáenlo cola sola presión de les sos garres.

Habita en montes trupos, tanto d'llanura como de monte, y ye raro que salga a campu abiertu. Alcuéntrase n'Europa, Asia y América septentrional. Apaez per tola península ibérica, sobremanera pel norte; sicasí, nun habita nes islles Baleares.

Añera nos árboles.[4] Nel ñeru deposita de 3 a 4 güevos (más raramente de 1 a 5) nun intervalu d'unos tres díes. Guaria la fema, que ye alimentada pol machu mientres el periodu qu'aquella dura, ye dicir ente 36 y 41 díes. Nes críes el plumaxe apaez ente los 18 y 38 díes; a los 40 díes aproximao salen del ñeru y a los 45 faen el so primer vuelu puramente dichu, algamando un eleváu grau d'independencia a los 70 díes.

El azor ye un terrible cazador del monte: escuerre les sos preses velozmente ente los árboles esnalando baxo con gran habilidá. Caza distintes especies d'aves (cuervos, palombos, tordos, perdices, etc) y tamién pequeños mamíferos (coneyos, llebres, esguiles, mures, etc), llagartos ya inseutos. Aveza a cazar a la chisba, posáu nuna talaya o llugar privilexáu dende au poder reparar el so territoriu y alcontrar a les sos posibles preses ensin ser vistu; una vegada alcontrada, ataca siguiendo'l so ángulu muertu, de normal dende embaxo nel casu d'un ave en vuelu, o a ras de suelu si la so presa ta nel suelu. Taramiella les sos preses nel llugar onde les atrapó.

Ye una ave diurna discreta y abondo malo de ver, inclusive más que'l so pariente de menor tamañu, el ferre (Accipiter nisus).

Conócense ocho subespecies d'Accipiter gentilis :[2]

El ferre o azorNOA (Accipiter gentilis) ye una especie d'ave accipitriforme de la familia Accipitridae. N'España, el so estáu de caltenimientu defínese como una especie d'esmolición menor (LC).

Tetraçalan (lat. Accipiter gentilis) - əsl qırğı cinsinə aid heyvan növü. Azərbaycanda təhlükədə olan quşlar siyahısına daxil edilmişdir.[1]

(III - VU). Həssas, sayı azalmaqda olan növdür.

Qarğadan iridir. Bel tərəfi qonur-boz, qarın tərəfi isə açıq rənglidir və üzərində nazik köndələn tünd zolaqlar var. Gözləri və ayaqları sarıdır .

Arealı genişdir: Avropa, Asiya, Şimal-Qərbi Afrika, Madaqaskar, Şimali Amerika. Azərbaycanda Talış və Şərqi Qafqaz dağ meşələrində yayılıb .

Hündür ağaclardan ibarət meşə quşudur. Daimi cütləri olur. Hər cüt yuva sahəsi seçir, oraya qonşu cütləri buraxmır. Hündür ağacda (10-15 m) yuva tikir. Şam ağacını xoşlayır. Berkut qartal (Aquila chrisaetus) kimi güclü yırtıcının yuvasını zəbt edə bilir. Eyni cütün sahəsində 2-3 yuva olur, hər il birində nəsil verir. Aprelin axırlarında 2-3 ədəd yaşıl çalarlı ağ yumurta verir. Dişi quş 32 gün kürt yatır, erkək onu yemləyir. Yem üçün yuvasından 5-6 km uzağa qədər uça bilir. Kannibalizmi güclüdür. Avqust ayında hər yuvada 1-2 bala pərvazlanır.

XX əsrə qədər adi saylı olub. XX əsrdə azalmağa başlayıb. 1950-ci illərdən sonra populyasiyasının sıxlığı azalıb nadir olub. XXI əsrin əvvəlində 55 cüt idi, indi isə 25 cütdən çox deyil. Son 10 ildə 36,4 % azalıb.

Zərərli yırtıcı hesab edilib ovlanması, ovçu quş kimi istifadə etmək üçün balalarının yuvadan götürülüb ələ öyrədilməsi, meşələrin qırılması, yem bazasının zəifləməsi və zəhərlənməsi, səs-küyün çoxalması.

Ovlanması qadağandır. Beynəlxalq ticarəti yasaqdır, Zaqatala və İlisu Dövlət Təbiət Qoruqlarında, Hirkan, Altıağac, Şahdağ və Göy-göl Milli Parklarında nəzarət altında saxlanılır. Azərbaycan Respublikasının və Naxçıvan MR-in Qırmızı kitablarına daxil edilib. CİTES, Bern və Bonn konvensiyalarına daxildir.

Yem bazasının qorunub saxlanılması, yuva sahəsindən ağac kəsilməsinin qarşısının alınması.

Tetraçalan (lat. Accipiter gentilis) - əsl qırğı cinsinə aid heyvan növü. Azərbaycanda təhlükədə olan quşlar siyahısına daxil edilmişdir.

Ar sparfell voan(Daveoù a vank), pe gwazsparfell (liester : gwazsparfelled, gwazsparfilli)[1], a zo ur spesad evned-preizh, Accipiter gentilis an anv skiantel anezhañ.

Anvet e voe Falco gentilis (kentanv) da gentañ-penn (e 1758)[2] gant an naturour svedat Carl von Linné (1707-1778).

Ar spesad a gaver an dek isspesad anezhañ[3] :

a vo kavet e Wikimedia Commons.

Ar sparfell voan(Daveoù a vank), pe gwazsparfell (liester : gwazsparfelled, gwazsparfilli), a zo ur spesad evned-preizh, Accipiter gentilis an anv skiantel anezhañ.

Anvet e voe Falco gentilis (kentanv) da gentañ-penn (e 1758) gant an naturour svedat Carl von Linné (1707-1778).

L'astor o falcó perdiguer (Accipiter gentilis) és un ocell de rapinya semblant a l'esparver i molt emprat en falconeria.

Aprofita els nius de còrvids o d'aligots per a niar. Pon 3 o 4 ous que cova durant 35-41 dies. Els petits encara necessitaran 35-40 dies per a volar.[1]

Perfectament camuflat en un arbre, es llança amb increïble perícia, entre branques i troncs, per caçar altres ocells (faisans, gaigs, còrvids, galls fers, perdius, aviram, etc.) i petits mamífers (conills, esquirols, talps, llebres, etc.).

Viuen als boscos fins a uns 2.000 m d'altitud i, de fet, als Països Catalans, es troba en quasi tota mena de bosc, fins i tot en els més frondosos, on no té cap dificultat per circular a gran velocitat.

A l'estiu, viuen al nord d'Europa i d'Àsia, i a la tardor baixen cap al sud i a l'Àfrica del Nord. També habita les regions temperades de Nord-amèrica.

Volen veloçment, amb un ràpid batre d'ales, o bé planen. És bastant sedentari i, igual que l'àliga daurada, es queda a la muntanya mentre dura l'hivern.

La seua supervivència es troba amenaçada per la destrucció dels boscos dels quals depenen les seues preses i ell mateix. De fet, aquesta va ésser una de les tres causes de la seua extinció al Regne Unit al llarg del segle XIX (les altres foren el col·leccionisme d'exemplars i la seua cacera per part dels guardaboscos per ser considerada una feristela). Actualment, ha tornat a aquell país per polítiques de reintroducció, exemplars vinguts del continent i d'altres escapats d'activitats de falconeria. Així, per exemple, ha esdevingut una espècie nombrosa a Northumberland.

L'astor o falcó perdiguer (Accipiter gentilis) és un ocell de rapinya semblant a l'esparver i molt emprat en falconeria.

Mae'r Gwalch Marth (Accipiter gentilis) yn aderyn rheibiol sy'n gyffredin trwy rannau helaeth o ogledd Ewrop, Asia a Gogledd America.

Yn y rhannau lle mae'r gaeafau'n arbennig o oer mae'n mudo tua'r de, ond mewn rhannau eraill, megis Gorllewin Ewrop, mae'n aros o gwmpas ei diriogaeth trwy'r flwyddyn.

Mae'n nythu mewn coed, ac yn hela adar, hyd at faint Ffesant ac anifeiliad hyd at faint Ysgyfarnog ambell dro. Mae'n medru symud yn gyflym drwy'r coed i ddal adar cyn iddynt wybod ei fod yno. Gellir adnabod y Gwalch Marth o'i gynffon hir ac adenydd gweddol fyr a llydan, sy'n ei alluogi i symud yn gyflym trwy'r coed. Mae'r ceiliog yn llwydlad ar ei gefn a llinellau llwyd ar y fron, tra mae'r iâr yn fwy llwyd tywyll gyda llai o liw glas ar y cefn. Gellir cymysgu rhwng y Gwalch Marth a'r Gwalch Glas ar brydiau, ond mae'r Gwalch Marth yn aderyn mwy o faint. Fel gyda'r Gwalch Glas, mae'r iâr yn fwy na'r ceiliog. Mae'r ceiliog rhwng 49 a 56 cm o hyd a 93–105 cm ar draws yr adenydd. Er fod y mesuriadau yma yn weddol debyg i iâr Gwalch Glas, mae'r Gwalch Marth yn edrych yn aderyn mwy. Mae'r iâr yn fwy o lawer, 58–64 cm o hyd a 108–127 cm ar draws yr adenydd, tua'r un faint a Bwncath.

Credir fod y Gwalch Marth wedi diflannu o Gymru erbyn y 19g, ond fod adar wedi eu rhyddhau yn ddiweddarach gan hebogwyr a'r rheini wedi ail-sefydlu'r boblogaeth. Mae wedi manteisio ar y fforestydd a blannwyd gan y Comisiwn Coedwigaeth, sy'n cynnig digon o le i nythu, ac mae'n debyg fod tua can pâr yn nythu yng Nghymru bellach, a'r nifer yn cynyddu.

Jestřáb lesní (Accipiter gentilis) je středně velký druh dravce z čeledi jestřábovitých (Accipitridae).

Jestřáb lesní je největší druh rodu Accipiter.[3] Samice dosahuje přibližně velikosti káně (délka těla 58–64 cm, rozpětí křídel 108–120 cm), samec je zhruba o třetinu menší (délka těla 49–56 cm, rozpětí křídel 90–105 cm). Hmotnost samce se pohybuje mezi 517–1170 g, samice v rozmezí 820–1509 g. Má krátká zakulacená křídla a dlouhý ocas, umožňující rychlé manévrování a prudké otočky v hustém lese. Svrchu je modrošedý (samec) nebo šedohnědý (samice), zespodu bílý, jemně černě proužkovaný. Temeno a tváře tmavé, kontrastující s výrazným bílým nadočním proužkem. Mladý pták je svrchu hnědý a zespodu béžově bílý s řídkým hnědým čárkováním. Nohy jsou žluté, duhovka dospělého oranžová až červená, mladého bledě nažloutlá.

V Evropě může být zaměněn s podobným, ale výrazně menším krahujcem obecným. V letu se liší o něco delšími a špičatějšími křídly, oblejšími cípy ocasu, širším kořenem ocasu a více vyčnívající hlavou, vsedě jsou důležitým rozpoznávacím znakem nohy, které jsou u jestřába lesního přibližně 3x silnější.[2][4][5]

Mimo hnízdní období se téměř neozývá, na hnízdišti vydává pronikavé „kekekekekekekekeke“.

Jestřáb lesní má holarktický typ rozšíření v lesním pásmu severní polokoule. Je převážně stálý nebo potulný, pouze nejsevernější populace jsou zčásti tažné. V průběhu 19. a 20. století došlo v Evropě k výraznému poklesu stavů, zapříčiněnému hlavně intenzivním pronásledováním a od 50. let 20. století také používáním pesticidů.[5] V posledních desetiletích evropská populace mírně narůstá, v roce 2004 v Evropě hnízdilo více než 160 000 párů.[6] Žije skrytě v lesích, hlavně ve vzrostlých jehličnatých porostech, za potravou občas zaletuje i do otevřené krajiny.