en

names in breadcrumbs

Regular passage visitor, winter visitor and resident breeder?

Marsh harriers are one of only two bird species – and the only bird of prey – where some of the males mimic females...

read more

The western marsh harrier (Circus aeruginosus) is a large harrier, a bird of prey from temperate and subtropical western Eurasia and adjacent Africa. It is also known as the Eurasian marsh harrier. Formerly, a number of relatives were included in C. aeruginosus, which was then known as "marsh harrier". The related taxa are now generally considered to be separate species: the eastern marsh harrier (C. spilonotus), the Papuan harrier (C. spilothorax) of eastern Asia and the Wallacea, the swamp harrier (C. approximans) of Australasia and the Madagascar marsh harrier (C. maillardi) of the western Indian Ocean islands.

The western marsh harrier is often divided into two subspecies, the widely migratory C. a. aeruginosus which is found across most of its range, and C. a. harterti which is resident all-year in north-west Africa.

The western marsh harrier was formally described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name Falco aeruginosus.[2] Linnaeus specified the locality as Europe but restricted this to Sweden in 1761.[3][4] The western marsh harrier is now placed in the genus Circus that was introduced by the French naturalist Bernard Germain de Lacépède in 1799.[5][6] The genus name Circus is derived from the Ancient Greek kirkos, referring to a bird of prey named for its circling flight (kirkos, "circle"), probably the hen harrier. The specific aeruginosus is Latin for "rusty".[7]

Two subspecies are recognised:[6]

The western marsh harrier is 48 to 56 cm (19 to 22 in) in length, has a wingspan of 115 to 130 cm (45 to 51 in) and a weight of 400 to 650 g (14 to 23 oz) in males and 550 to 800 g (19 to 28 oz) in females.[8] It is a large, bulky harrier, larger than other European harriers, with fairly broad wings, and is sexually dimorphic. The male's plumage is mostly a cryptic reddish-brown with lighter yellowish streaks, which are particularly prominent on the breast. The head and shoulders are mostly pale greyish-yellowish. The rectrices and the secondary and tertiary remiges are pure grey, the latter contrasting with the brown forewing and the black primary remiges at the wingtips. The upperside and underside of the wing look similar, though the brown is lighter on the underwing. Whether from the side or below, flying males appear characteristically three-colored brown-grey-black.[9] The legs, feet, irides and the cere of the black bill are yellow.[10]

The female is almost entirely chocolate-brown. The top of the head, the throat and the shoulders have of a conspicuously lighter yellowish colour; this can be clearly delimited and very contrasting, or (particularly in worn plumage) be more washed-out, resembling the male's head colours. But the eye area of the female is always darker, making the light eye stand out, while the male's head is altogether not very contrastingly coloured and the female lacks the grey wing-patch and tail. Juveniles are similar to females, but usually have less yellow, particularly on the shoulders.[9]

There is a rare hypermelanic morph with largely dark plumage. It is most often found in the east of the species' range. Juveniles of this morph may look entirely black in flight.

This species has a wide breeding range from Europe and northwestern Africa to Central Asia and the northern parts of the Middle East. It breeds in almost every country of Europe but is absent from mountainous regions and subarctic Scandinavia. It is rare but increasing in Great Britain where it has spread as far as eastern Scotland.[11] In the Middle East there are populations in Turkey, Iraq, and Iran, while in Central Asia the range extends eastwards as far as north-west China, Mongolia, and the Lake Baikal region of Siberia.

Most populations of the western marsh harrier are migratory or dispersive. Some birds winter in milder regions of southern and western Europe, while others migrate to the Sahel, Nile basin and Great Lakes region in Africa, or to Arabia, the Indian subcontinent, and Myanmar. The all-year resident subspecies harterti inhabits Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia.

Vagrants have reached Iceland, the Azores, Malaysia, and Sumatra. The first documented (but unconfirmed) record for the Americas was one bird reportedly photographed on 4 December 1994 at Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge in Accomack County, Virginia. Subsequently, there were confirmed records from Guadeloupe (winter of 2002/2003), from Laguna Cartagena National Wildlife Refuge in Puerto Rico (early 2004 and January/February 2006)[12][13][14] and in Bermuda (December 2015).[15]

Like the other marsh harriers, it is strongly associated with wetland areas, especially those rich in common reed (Phragmites australis). It can also be met with in a variety of other open habitats, such as farmland and grassland, particularly where these border marshland. It is a territorial bird in the breeding season, and even in winter it seems less social than other harriers, which often gather in large flocks.[16] But this is probably simply due to habitat preferences, as the marsh harriers are completely allopatric while several of C. aeruginosus grassland and steppe relatives winter in the same regions and assemble at food sources such as locust outbreaks. Still, in Keoladeo National Park of Rajasthan (India) around 100 Eurasian marsh harriers are observed to roost together each November/December; they assemble in tall grassland dominated by Desmostachya bipinnata and vetiver (Chrysopogon zizanioides), but where this is too disturbed by human activity they will use floating carpets of common water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) instead – the choice of such roost sites may be to give early warning of predators, which will conspicuously rustle through the plants if they try to sneak upon the resting birds[17]

The start of the breeding season varies from mid-March to early May. Western marsh harrier males often pair with two and occasionally three females. Pair bonds usually last for a single breeding season, but some pairs remain together for several years.

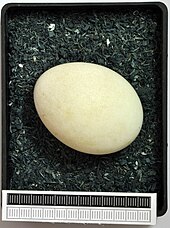

The ground nest is made of sticks, reeds and grasses. It is usually built in a reedbed, but the species will also nest in arable fields. There are between three and eight eggs in a normal clutch. The eggs are oval in shape and white in colour, with a bluish or greenish tinge when recently laid. The eggs are incubated for 31–38 days and the young birds fledge after 30–40 days.[18]

It hunts in typical harrier fashion, gliding low over flat open ground on its search for prey, with its wings held in a shallow V-shape and often with dangling legs. It feeds on small mammals, small birds, insects, reptiles, and frogs.[19][20]

The western marsh harrier declined in many areas between the 19th and the late 20th centuries due to persecution, habitat destruction and excessive pesticide use. It is now a protected species in many countries. In Great Britain, the population was likely extinct by the end of the 19th century. A single pair in Horsey, Norfolk bred in 1911, and by 2006, the Rare Breeding Birds Panel had recorded at least 265 females rearing 453 young. It made a comeback in Ireland as well, where it had become extinct in 1918.[21]

It still faces a number of threats, including the shooting of birds migrating through the Mediterranean region. They are vulnerable to disturbance during the breeding season and also liable to lead shot poisoning. Still, the threats to this bird have been largely averted and it is today classified as Species of Least Concern by the IUCN.[1]

The western marsh harrier (Circus aeruginosus) is a large harrier, a bird of prey from temperate and subtropical western Eurasia and adjacent Africa. It is also known as the Eurasian marsh harrier. Formerly, a number of relatives were included in C. aeruginosus, which was then known as "marsh harrier". The related taxa are now generally considered to be separate species: the eastern marsh harrier (C. spilonotus), the Papuan harrier (C. spilothorax) of eastern Asia and the Wallacea, the swamp harrier (C. approximans) of Australasia and the Madagascar marsh harrier (C. maillardi) of the western Indian Ocean islands.

The western marsh harrier is often divided into two subspecies, the widely migratory C. a. aeruginosus which is found across most of its range, and C. a. harterti which is resident all-year in north-west Africa.