en

names in breadcrumbs

Toxoplasma gondii(tŏk'sə-plāz'mə gŏn'dē-ī') is anobligate,intracellular,parasiticprotozoanthat causes the diseasetoxoplasmosis.[1]

Found worldwide,T. gondiiis capable of infecting virtually allwarm-bloodedanimals.[2]In humans, it is one of the most common parasites;[3]serologicalstudies estimate that up to a third of the global population has been exposed to and may be chronically infected withT. gondii, although infection rates differ significantly from country to country.[4]Although mild, flu-like symptoms occasionally occur during the first few weeks following exposure, infection withT. gondiigenerally produces no symptoms in healthy human adults.[5][6]However, in infants,HIV/AIDSpatients, and others withweakened immunity, infection can cause serious and occasionally fatal illness (toxoplasmosis).[5][6]

Infection in humans and other warm-blooded animals can occur

AlthoughT. gondiican infect, be transmitted by, andasexually reproducewithin humans and virtually all other warm-blooded animals, the parasite cansexually reproduceonly within theintestinesof members of thecat family (felids).[8]Felids are therefore defined as thedefinitive hostsofT. gondii, with all other hosts defined as intermediate hosts.

T. gondiihas been shown to alter the behavior of infectedrodentsin ways thought to increase the rodents' chances of beingpreyedupon by cats.[9][10][11]Because cats are the only hosts within whichT. gondiican sexually reproduce to complete and begin its lifecycle, such behavioral manipulations are thought to beevolutionary adaptationsto increase the parasite'sreproductive success,[11]in one of the manifestations the evolutionary biologistRichard Dawkinsattributes to the "extended phenotype". Although numerous hypotheses exist and are being investigated, the mechanism ofT. gondii–induced behavioral changes in rodents remains unknown.[12]

A number of studies have suggested subtle behavioral or personality changes may occur in infected humans,[13]and infection with the parasite has recently been associated with a number ofneurological disorders, particularlyschizophrenia.[10]However, evidence forcausalrelationships remains limited.[10]

Toxoplasma gondii is an apicomplexan protozoan parasite that infects most species of warm-blooded animals, including humans, and can cause the disease toxoplasmosis. Serologic prevalence data indicate that toxoplasmosis is one of the most common of humans infections throughout the world. A high prevalence of infection in France has been related to a preference for eating raw or undercooked meat, while a high prevalence in Central America has been related to the frequency of stray cats in a climate favoring survival of oocysts and soil exposure. The overall seroprevalence in the United States among adolescents and adults, as determined with specimens collected by the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) between 1988 and 1994, was found to be 22.5%, with a seroprevalence among women of childbearing age (15 to 44 years) of 15%.

The only known definitive hosts for Toxoplasma gondii are members of family Felidae (domestic cats and their relatives). Unsporulated oocysts are shed in the cat’s feces. Although oocysts are usually only shed for 1-2 weeks, large numbers may be shed. Oocysts take 1-5 days to sporulate in the environment and become infective. Intermediate hosts in nature (including birds and rodents) become infected after ingesting soil, water or plant material contaminated with oocysts. Oocysts transform into tachyzoites shortly after ingestion. Thes tachyzoites localize in neural and muscle tissue and develop into tissue cyst bradyzoites. Cats become infected after consuming intermediate hosts harboring tissue cysts. Cats may also become infected directly by ingestion of sporulated oocysts. Animals bred for human consumption and wild game may also become infected with tissue cysts after ingestion of sporulated oocysts in the environment. Humans can become infected by any of several routes:

In the human host, the parasites form tissue cysts, most commonly in skeletal muscle, myocardium, brain, and eyes; these cysts may remain throughout the life of the host. Diagnosis is usually achieved by serology, although tissue cysts may be observed in stained biopsy specimens. Diagnosis of congenital infections can be achieved by detecting T. gondii DNA in amniotic fluid using molecular methods such as PCR.

Toxoplasma gondii is 'n eukariotiese sporosoo wat die katsiekte toksoplasmose veroorsaak.

Die genus Toxoplasma is monotipies. Dit wil sê dat T. gondii die enigste spesie in hierdie genus is.

Die eintlike gasheer van hierdie obligate parasiet is lede van die familie Felidae waartoe die huiskat behoort. Die ongesporuleerde oösiste word in die kat se uitwerpsel uitgeskei. Dit duur 1 tot 5 dae voor die siste sporuleer en besmetlik raak.

Die natuurlike sekondêre gashere is voëls en knaagdiere wat grond, water of plantmateriaal wat besmet is drink of vreet. In die sekondêre gasheer vorm die oösiste tagisoïete wat in die senuwee- en spierweefsel innestel en bradisoïet-siste vorm. Katte vreet hierdie vleis en raak besmet.[1] 'n Deel van die bradisoïete vorm gametosiete wat manlik of vroulik is en seksueel in die kat voortplant.

Mense kan op verskeie maniere besmet raak:

Daar is navorsing wat toon dat die parasiet die gedrag van die besmette sekondêre gasheer beïnvloed, byvoorbeeld dat geïnfekteerde rotte 'n verminderde afkeur vir die kat se urine ondervind, en ook makliker as prooi gevang word deur katte.

Toxoplasma gondii is 'n eukariotiese sporosoo wat die katsiekte toksoplasmose veroorsaak.

Die genus Toxoplasma is monotipies. Dit wil sê dat T. gondii die enigste spesie in hierdie genus is.

Toxoplasma gondii és una espècie de protozou paràsit causant de la toxoplasmosi, una malaltia en general lleu, però que es pot complicar fins a esdevenir fatal, especialment en els gats i en els fetus humans.[1] El gat és el seu hoste definitiu, encara que altres animals homeoterms com els humans també poden allotjar-lo. Per exemple, ha estat aïllat a dofins, llúdries marines,[2] morses,[3] linxs,[4] isards,[5] oques salvatges[6] i diferents tipus de bestiar.[7] També infecta les gavines,[8] les cigonyes i les aus rapinyaires.[9] S'ha observat una alta prevalença de T. gondii entre els pollastres de corral que viuen sobre sòls contaminats i la carn dels exemplars infectats és una font comuna d'adquisició del paràsit.[10] A més, es creu que en aquests animals la presència del paràsit facilita la coccidiosi cecal provocada per un altre protozou patogen, Eimeria tenella, existint in vitro una interacció entre els dos microorganismes.[11] Rattus norvegicus és el rosegador amb l'índex infectiu més elevat i un element d'importància en la disseminació del protozou.[12]

T. gondii es considera l'única espècie vàlida del gènere Toxoplasma. Estudis epidemiològics moleculars, però, han posat de manifest l'existència de com a mínim quatre llinatges clonals en el paràsit, caracteritzats pel seu grau de virulència en múrids de laboratori.[13]

Fou descobert l'any 1908 per diferents investigadors a la sang del rosegador africà Ctenodactylus gundi i a la d'un conill del Brasil, encara que el seu cicle vital complert no es conegué fins 60 anys més tard.[14] La primera prova serològica per detectar-lo va ser creada el 1948.[15]

Aquest protozou és present als cinc continents i s'estima que infecta a un 25-30% de la població mundial. La prevalença de la infecció varia molt entre països i també entre les diferents comunitats que habiten una mateixa regió. La seroprevalença més baixa es dóna a Nord-amèrica, al Sud-est asiàtic, a l'Europa del Nord i al Sàhara. A l'Europa central i del sud la prevalença és moderada, sent la més alta la corresponent a l'Amèrica del Sud i l'Àfrica tropical.[16]

És un paràsit que ha creat diferents rutes potencials de transmissió entre diferents espècies d'hoste i també entre una mateixa espècie. Si T. gondii s'adquireix durant la gestació pot ser transmès verticalment pels taquizoïts al fetus a través de la placenta, ocasionant una toxoplasmosi congènita.[17] Els efectes lesius del protozou sobre el fetus són especialment importants en el cas que la infecció materna tingui lloc en el tercer trimestre d'embaràs,[18] No totes les primoinfeccions per T. gondii en dones gestants comporten una toxoplasmosi neonatal. Segons dades de l'any 2007, un 61% d'elles no transmeten la infecció al fetus. Pel que fa a la resta de casos el 26% dels nounats pateixen una infecció subclínica i el 13% presenta signes clínics aguts (7%) o moderats (6%). La prevalença d'aquestes primoinfeccions varia molt en funció de la zona geogràfica en particular, oscil·lant entre 1 i 14 casos/1.000 embarassos.[19] La hidrocefàlia, les calcificacions cerebrals i els danys oculars són patologies greus pròpies de la infecció congènita pel protozou. La toxoplasmosi també és una de les causes de part preterme, possiblement infradiagnosticada a molts països per manca de programes de detecció.[20] La infecció materna pel paràsit origina nombrosos avortaments espontanis i altera la normal proporció entre els dos sexes de la descendència humana.[21] T. gondii és l'agent patogen responsable de molts casos de retinocoroïditis en nens[22] i adults.[23] Rares vegades, aquest protozou provoca hepatitis agudes.[24] En persones immunodeprimides desencadena infeccions oportunistes molt serioses[25] i que sovint afecten al SNC, com ara encefalitis,[26] meningitis,[27] o abscessos cerebrals,[28] ja que el microorganisme té un marcat neurotropisme i és capaç de travessar la barrera hematoencefàlica.[29] És una causa excepcional de granulomes al tronc de l'encèfal[30] o de mielitis transversa en individus sense problemes d'immunitat.[31] S'ha relacionat la infecció latent pel paràsit amb la gènesi de diversos trastorns neuropsiquiàtrics,[32][33][34] encara que no existeixen evidències concloents fonamentades en estudis poblacionals que confirmin aquest supòsit.[35] Un grup d'investigadors, emprant tècniques proteòmiques i d'espectrometria de masses, ha demostrat en un model murí que la infecció crònica per T. gondii ocasiona canvis neuroinflamatoris que alteren profundament la composició proteínica dels processos sinàptics.[36] Es creu que en animals com ara els ximpanzés[37] o les rates[38] el paràsit és la causa de modificacions del comportament tendents a facilitar la seva propagació.

La transmissió horitzontal d'aquest protozou involucra tres estadis del seu cicle vital. Per exemple, ooquists infecciosos es poden adquirir de medis contaminats (en especial l'aigua)[39] o poden ingerir-se quists tissulars o taquizoïts continguts en la carn o les vísceres de molts animals.

S'ha comprovat que l'aigua és una font important de toxoplasmosis en països tropicals i subtropicals que utilitzen aigües de superfície sense purificar pel consum humà. El brot millor documentat, però, de toxoplasmosi aguda en humans provocat per aigua contaminada fou el de la població de Victoria (Vancouver Island, Canadà), l'any 1995. Estudis epidemiològics retrospectius demostraren que la causa del brot va ser la presència d'ooquists a la xarxa municipal de distribució d'aigua potable.[40]

La transmissió pot ocórrer també per mitjà de taquizoïts presents en productes sanguinis, teixits per trasplantament o llet sense pasteuritzar[41] i formatges artesanals fets amb llet crua. Segons un estudi realitzat amb dades de diversos països europeus corresponents al període 2010-2014, l'índex de mortalitat causat per aquest protozou entre els receptors de trasplantaments en general és d'un 17%, observant-se una menor supervivència en malalts T. gondii seropositius, trasplantats hepàtics i receptors de trasplantament al·logènic de cèl·lules mare hematopoiètiques.[42] En el passat, el consum de carn crua o poc cuita de porc o de xai era la principal via de transmissió als humans. Avui dia, i des de l'increment de les immunodeficiències adquirides, la facilitació de la mobilitat poblacional i l'augment del consum i tràfic de la carn d'animals salvatges (bushmeat), es desconeix quina modalitat de transmissió global és la més important epidemiològicament.[43] Les estimacions de l'OMS indiquen que a Europa es produeixen cada any més d'un milió d'infeccions per T. gondii transmeses per via alimentària.[44] A l'Estat espanyol, la seroprevalença en dones embarassades oscil·la entre el 11 i el 28%, depenent del territori i l'any d'estudi, mentre que la incidència de toxoplasmosi gestacional és del 1,9‰. A hores d'ara la infecció per aquest paràsit no és una malaltia de declaració obligatòria.[45] Les dades d'un estudi de l'any 2010 mostraven una seropositivitat del 19% entre els porcs de granja de Catalunya.[46]

El contacte de les mucoses ocular i bucal amb material portador del paràsit és també una via d'adquisició de la toxoplasmosi que ha estat amb certa freqüència la font infecciosa en treballadors de laboratori (el seu nivell de contenció és 2),[47] jardiners o personal de neteja. També es pot adquirir la infecció toxoplàsmica per via parenteral i s'han registrat múltiples casos de puncions, petites ferides o erosions -produïdes durant la manipulació de teixits o materials portadors del protozou- causants de toxoplasmosis ocupacionals.[48] La inhalació és una via infectiva inusual, però possible. No hi ha constància de la transmissió de T. gondii a través de l'alletament o per contacte humà-humà. Una altra via potencial és la picada de paparres. Aquests àcars es consideren transmissors mecànics del protozou, independentment de la seva fase de vida.[49] A Europa T. gondii ha estat aïllat a Ixodes ricinus[50] i a Dermacentor reticulatus, unes paparres molt comunes a zones boscoses,[51] fet que explicaria la seva presència a certes espècies d'herbívors. No totes les paparres són vectors del paràsit a través de les picades. Per exemple, la sang infectada present a l'espècie oriental Haemaphysalis longicornis no té experimentalment capacitat transmissora; en canvi, la ingestió de l'aràcnid es considera una ruta vàlida d'infecció.[52]

Segons els criteris de la xarxa Euro-FBP,[53] en l'avaluació d'un conjunt de 30 països europeus, T. gondii ocupa el segon lloc en el rànquing de prioritats relacionades amb microorganismes causants de malalties parasitàries transmeses pels aliments.[54]

Pel que fa a la infecció aguda en gestants, un estudi multicèntric europeu atribuí l'adquisició del protozou al consum de carns poc cuites o curades en un 30-63% dels casos investigats i en un 6%-17% al contacte amb sòls contaminats. Un altre motiu relacionat va ser el fet de viatjar fora d'Europa o dels EUA i Canadà. El contacte amb gats no fou un factor de risc d'importància, segons els resultats de dit estudi.[55]

La virulència de les diverses soques del paràsit és variable i depèn de l'expressió o no de certes proteïnes en la paret dels ooquists.[56]

Els taquizoïts i els bradizoïts són sensibles a l'etanol al 70% i a solucions d'1% d'hipoclorit sòdic. L'ooquist és sensible al iode i al formol. Els ooquists s'inactiven a temperatures superiors a 66ºC en menys de 10 minuts. Els taquizoïts s'inactiven a 67ºC i per congelació a -15ºC al menys durant 3 dies o bé a -20ºC al menys durant 2 dies.[57]

Els ooquists poden mantenir en l'aigua de mar el seu potencial infecciós durant molts mesos o un any i no s'ha descobert fins ara cap animal marí amb capacitat d'expulsar-los per ell mateix. Per tant, cal atribuir la seva presència al mar a la contaminació de l'ecosistema aquàtic per ooquists d'origen terrestre, un fenomen afavorit per l'augment de la població en les zones costaneres i de successos meteorològics extrems.[58] La detecció de T. gondii a balenes beluga de regions àrtiques amb molt escassa presència humana o de fèlids i el fet que sigui una espècie que s'alimenta de preses ectotèrmiques (invertebrats i peixos) fa pensat que aquests animals poden actuar com a transmissors marins passius del paràsit.[59]

L'ooquist és la fase esporulada de certs protistes, incloent els gèneres Toxoplasma i Cryptosporidium. Aquest és un estat en el que el microorganisme pot sobreviure per llargs períodes de temps fora de l'hoste per la seva alta resistència a factors del medi ambient, gràcies a la seva doble paret. Dita paret té una organització polimèrica complexa que permet a l'ooquist suportar molts tipus d'agressions físiques i químiques, incloent els raigs UV, l'ozó o les solucions clorades.[60] Algunes de les proteïnes de la paret són específiques d'aquesta fase vital de T. gondii i no estan presents als bradizoïts o als taquizoïts, particularitat que pot ser emprada per millorar la identificació de les espores en mostres ambientals.[61] L'anàlisi proteòmica dels ooquists indica que posseeixen també un grup de proteïnes amb un perfil funcional que fa possible l'adaptació d'aquells a medis extracel·lulars pobres en nutrients mentre arriben a la maduresa.[62] Els ooquists presents al sòl poden ser disseminats mecànicament per les condicions meteorològiques o per artròpodes o anèl·lids.

El bradizoït (del prefix grec bradýs=lent i del sufix zōo=animal) és la forma de replicació lenta del paràsit. No solament de Toxoplasma gondii, sinó també d'altres protozous responsables d'infeccions parasitàries, com ara Neospora caninum[63] o Besnoitia oryctofelisi.[64] A la toxoplasmosi latent (crònica), el bradizoït es presenta en conglomerats microscòpics envoltats per una paret quística, en el múscul i/o el teixit cerebral infectat.[65] Els bradizoïts presenten molts trets ultraestructurals que els diferencien dels taquizoïts: tenen un nucli situat a l'extrem posterior, roptries sòlides (un tipus d'orgànul secretor especial) nombrosos micronemes i grànuls d'amilopectina.[66] Als bradizoïts no es veuen cossos lipídics, mentre que són abundants en els esporozoïts dels ooquists i apareixen ocasionalment en els taquizoïts. Els bradizoïts són PAS+ i els taquizoïts no.[67]

Els taquizoïts són formes de vida latent que formen quists en teixits infestats pel toxoplasma o altres paràsits (per exemple l'esmentat Neospora caninum, un coccidi que té moltes similituds estructurals amb T. gondii). Els taquizoïts es troben en vacúols dins de les cèl·lules infestades. Són estructures fràgils, que no resisteixen la dessecació ni l'ebullició i sensibles a molts desinfectants (per exemple hipoclorit de sodi al 1% o etanol al 70%). Els quists tissulars s'inactiven per congelació a -15ºC al menys durant 3 dies o a -20ºC al menys 2 dies. Poden sobreviure fins a tres setmanes a 1-4°C.[68] S'ha observat in vitro i in vivo que l'extret de taquizoïts té propietats immunomoduladores contra la sensibilització al·lèrgica i la inflamació de vies aèries.[69]

Algunes de les de les qüestions claus relacionades amb aquesta fase del cicle de T. gondii, encara no aclarides del tot pels investigadors, són els múltiples factors intrínsecs i extrínsecs que condicionen el moment i el mecanisme de sortida dels taquizoïts de la cèl·lula hoste.[70] Se sap que els taquizoïts es poden desplaçar per lliscament gràcies a moviments de rotació helicoïdal en sentit horari, producte de successives torsions de la seva membrana externa.[71]

La licocalcona A (un tipus de calcona existent a les arrels de les plantes del gènere Glycyrrhiza), inhibeix experimentalment la proliferació dels taquizoïts de la soca virulenta RH[72] de T. gondii.[73] Un nou decapèptid sintètic, anomenat KP, indueix la mort dels taquizoïts a través de fenòmens apoptòtics, sense provocar danys en les cèl·lules hoste.[74]

L'àcid ursòlic mostra una alta activitat contra T. gondii en murins infectats amb taquizoïts del paràsit, ja que inhibeix eficaçment el seu procés proliferatiu al bloquejar la formació de vacúols parasitòfors en la membrana de les cèl·lules hoste.[75]

El cicle de vida del T. gondii té dues fases. La fase sexual del cicle de vida passa només en membres de la família Felidae (gats domèstics i salvatges), fent que aquests animals siguin els hostes primaris del paràsit. En gats domèstics, la seroprevalença de T. gondii varia segons les races i l'edat de l'animal, a banda del tipus de menjar que ingereix.[76] La fase asexual del cicle de vida pot ocórrer en qualsevol animal de sang calenta, com ara altres mamífers i aus. Per això, la toxoplasmosi és una zoonosi parasitària.[77]

En l'hoste intermediari, incloent els felins, els paràsits envaeixen cèl·lules, formant un compartiment anomenat vacúol parasitòfor[78] que contenen bradizoïts, la forma de replicació lenta del paràsit.[79] Els vacúols formen quists en els teixits, especialment en els músculs i el cervell. Com que el paràsit està dins de les cèl·lules, el sistema immunitari de l'hoste no detecta aquests quists. La resistència als antibiòtics varia, però els quists són difícils d'erradicar totalment. El T. gondii es propaga dins d'aquests vacúols per una sèrie de divisions binàries fins que la cèl·lula infestada eventualment es trenca, alliberant als taquizoïts. Aquests tenen motilitat i constitueixen la forma de reproducció asexual del paràsit. A diferència dels bradizoïts, els taquizoïts lliures són eficaçment eliminats per la immunitat de l'hoste, tot i que alguns aconsegueixen infectar altres cèl·lules formant bradizoïts, mantenint així el cicle de vida d'aquest paràsit. De forma contrària als taquizoïts dins dels vacúols parasitòfors, els bradizoïts dels quists tissulars mostren una gran heterogeneïtat fisiològica i de capacitat de replicació. El fet que els quists tissulars tinguin mides diferents suggereix que són estructures de creixement dinàmic amb un paper actiu en la infecció crònica per T. gondii i no solament quists en estat de repòs i metabòlicament inerts.[80]

Els quists tissulars són ingerits per el gat (per exemple, a l'alimentar-se d'un ratolí infectat). Si l'animal no pateix un dèficit immunitari no presenta cap alteració clínica. En cas contrari, el paràsit afecta predominantment el SNC, els músculs, el pulmons i els ulls del felí, sent la clindamicina el tractament electiu. Més del 50% dels gats, sobretot els que volten lliurament, mostren en els exàmens serològics anticossos que indiquen infecció i presència de quists de T. gondii. Els gats amb anticossos positius, però, no estan en la fase d'alliberament d'ooquists i no representen un risc zoonòtic.[81] Els quists sobreviuen el pas per l'estómac del gat i els paràsits infecten les cèl·lules epitelials de l'intestí prim, en les quals té lloc la reproducció sexual i la formació d'ooquists que són alliberats amb la femta entre els 3-10 dies posteriors a la ingesta dels quists i que es poden mantenir viables a l'aire lliure 46 dies a temperatures d'entre 6-36ºC.[82] La femta fresca no és pròpiament infecciosa, ja que els ooquists necessiten un o dos dies per esporular-se després del canvi de medi. Altres animals, incloent-hi els humans ingereixen els ooquists (en menjar vegetals no rentats adequadament) o els quists tissulars al menjar carn crua o cuita de forma insuficient. Els paràsits entren als macròfags de la paret intestinal per després distribuir-se per la circulació sanguínia i el cos sencer.

Si bé existeixen vacunes que produeixen un cert nivell d'immunitat contra T. gondii en gats, encara no s'ha aconseguit una vacuna d'ús humà.[83] Vacunes creades a partir d'una soca determinada del paràsit, la S48, han donat bons resultats reduint la formació de quists en la carn d'ovelles i porcs.[84] Una línia d'especial interès dins d'aquest camp de recerca és la del disseny de vacunes d'ADN basades en proteïnes produïdes pels micronemes (un tipus de orgànuls secretors existents a l'apicomplex del paràsit).[85]

Un grup d'investigadors xinesos realitza a hores d'ara assajos en ratolins amb una vacuna anomenada HSP60 DNA. Els resultats preliminars indiquen que podria ser una candidata vàlida pel desenvolupament d'un adequat grau de protecció contra la toxoplasmosi humana aguda i crònica.[86]

Habitualment, la detecció de T. gondii requereix procediments relativament lents i costosos. S'ha assajat un nou test que utilitza la tècnica d'immunocromatrografia de flux lateral per identificar d'una forma ràpida, eficaç i econòmica la presència del patogen en sang total amb una senzilla punxada al dit.[87] Ha estat dissenyada una plataforma automàtica de rastreig d'imatge d'alt contingut[88] que permet avaluar l'acció inhibitòria de noves molècules amb potencial terapèutic sobre la proliferació del paràsit.[89]

Toxoplasma gondii és una espècie de protozou paràsit causant de la toxoplasmosi, una malaltia en general lleu, però que es pot complicar fins a esdevenir fatal, especialment en els gats i en els fetus humans. El gat és el seu hoste definitiu, encara que altres animals homeoterms com els humans també poden allotjar-lo. Per exemple, ha estat aïllat a dofins, llúdries marines, morses, linxs, isards, oques salvatges i diferents tipus de bestiar. També infecta les gavines, les cigonyes i les aus rapinyaires. S'ha observat una alta prevalença de T. gondii entre els pollastres de corral que viuen sobre sòls contaminats i la carn dels exemplars infectats és una font comuna d'adquisició del paràsit. A més, es creu que en aquests animals la presència del paràsit facilita la coccidiosi cecal provocada per un altre protozou patogen, Eimeria tenella, existint in vitro una interacció entre els dos microorganismes. Rattus norvegicus és el rosegador amb l'índex infectiu més elevat i un element d'importància en la disseminació del protozou.

T. gondii es considera l'única espècie vàlida del gènere Toxoplasma. Estudis epidemiològics moleculars, però, han posat de manifest l'existència de com a mínim quatre llinatges clonals en el paràsit, caracteritzats pel seu grau de virulència en múrids de laboratori.

Fou descobert l'any 1908 per diferents investigadors a la sang del rosegador africà Ctenodactylus gundi i a la d'un conill del Brasil, encara que el seu cicle vital complert no es conegué fins 60 anys més tard. La primera prova serològica per detectar-lo va ser creada el 1948.

Aquest protozou és present als cinc continents i s'estima que infecta a un 25-30% de la població mundial. La prevalença de la infecció varia molt entre països i també entre les diferents comunitats que habiten una mateixa regió. La seroprevalença més baixa es dóna a Nord-amèrica, al Sud-est asiàtic, a l'Europa del Nord i al Sàhara. A l'Europa central i del sud la prevalença és moderada, sent la més alta la corresponent a l'Amèrica del Sud i l'Àfrica tropical.

Toxoplasma gondii (Nicolle et Manceaux, 1908) je vnitrobuněčný parazitický prvok, vícehostitelská kokcidie, která parazituje v buňkách člověka i zvířat. Jejím definitivním hostitelem jsou kočkovité šelmy, mezihostitelem se může stát většina teplokrevných živočichů včetně člověka.[1] Způsobuje toxoplazmózu, u těhotných žen hrozí při infekci tímto prvokem narození postiženého dítěte. U HIV pacientů může způsobit akutní zánět mozku.[2] Rovněž může způsobit aborty u ovcí a koz.[3]

V trusu koček se ven dostávají tzv. oocysty, které následně sporulují a vydrží v prostředí velmi dlouhou dobu. Když je však požije s kontaminovanou potravou nějaký teplokrevný živočich, z oocyst vzniknou tzv. tachyzoiti (řec. tachos – rychlost), kteří rychle zaplaví nervovou a svalovou tkáň a postupně z nich vzniknou bradyzoiti (řec. brady – pomalý), kteří v mezihostiteli vydrží pravděpodobně celý život v zapouzdřeném stavu. Kočka (definitivní hostitel) se může nakazit několika způsoby: buď tím, že sežere maso obsahující bradyzoity, nebo někdy i potravou obsahující oocysty. Ve střevě kočky dochází k množení a tvorbě oocyst ve střevních buňkách.[1][4]

Toxoplasma gondii využívá specifický způsob pohybu (lze pozorovat například i u jiného druhu z kmene Apicomplexa Plasmodium falciparum), nazývaný "gliding motility", v překladu klouzání. Tento druh pohybu je založený na aktino-myosinovém komplexu zakotveném v tzv. "inner membrane complex", což je dvojice membrán situovaná pod parazitovu plazmatickou membránu. Tento komplex se přes transmembránové proteiny vylučované z jeho sekrečních organel váže na substrát a umožňuje dynamický pohyb beze změny tvaru parazita.[5]

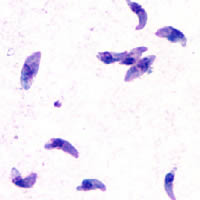

Tachyzoit je oproti bradyzoitu mohutnější a má centrálně situované, dobře patrné jádro. Bradyzoit má jádro spíše v posteriorní části.

Klíčová je přítomnost apikálního komplexu, což je soubor organel na anteriorním pólu zoitu, který hraje nezastupitelnou roli v invazi do hostitelských buněk. Zahrnuje konoid, což je trubicovitá mikrotubulární struktura, jejíž báze je obrkoužena apikálními prstenci a středem prochází dva mikrotubuly. Mezi sekreční organely patří mikronemy a kyjovité rhoptrie. Pro Toxoplasmu je typická přítomnost organely zvané apikoplast, která vznikla endosymbiózou a obsahuje vlastní kruhovou DNA.[6]

Čerstvý oocyst se v mikroskopu jeví jako koule s mnoha jemnými skvrnkami. Přibližně za 48-72 hodin dozraje do podoby kuličky velké 10-12 mikrometrů, ve které jsou dobře zřetelné dvě sporocysty.

V hostiteli se vylíhne podlouhlý prvok dlouhý 4-8 a silný 2-3 mikrometry, se zužujícím se předním koncem a tupým zadním. Uvnitř je dobře patrné jádro.

Zralé cysty ve tkáni jsou 5-50 mikrometrů velké. V mozku mají kulový tvar, v srdečních a kosterních svalech podlouhlý.

Člověk je pro Toxoplasmu náhodným mezihostitelem a v podstatě se Toxoplasma z člověka nemá šanci dostat do kočky jako definitivního hostitele a zakončit tak svůj životní cyklus. Lidé se obvykle nakazí nedostatečně tepelně zpracovaným masem (požitím bradyzoitů) nebo požitím oocyst z prostředí.[1] Infekce prvokem T. gondii není u lidí nijak vzácná: např. ve Francii nebo v Německu se Toxoplasmou v průběhu života nakazí 80 % populace, v Česku asi třetina obyvatel, v rámci celého světa přibližně 50 %.[7] Toxoplasmóza je však obvykle bez viditelných příznaků, může se vyskytnout asymptomatická generalizovaná lymfadenopatie. V největším nebezpečí jsou těhotné ženy, které se do té doby s parazitem nesetkaly – hrozí riziko poškození plodu.[1] U imunokompromitovaných osob (např. AIDS) může toxoplazmóza vyvolat závažné poškození CNS.

Udává se, že T. gondii může manipuluvat s lidským chováním. Lidé s Toxoplasmou reagují pomaleji v kritických situacích – pramení to z prosté skutečnosti, že Toxoplasma „ví“, že myši s pomalejšími reakcemi se snadno stanou úlovkem koček. Toxoplazmóza (především u Rh-negativních lidí) podle některých výzkumů zvyšuje pravděpodobnost, že nakažený člověk se – v důsledku pomalejších reakcí – stane např. účastníkem dopravní nehody[7][8] apod. Tomuto výzkumu však odporují jiné studie, která souvislosti mezi nákazou toxoplazmózou a např. právě účastí v dopravních nehodách (a řadou dalších způsobů chování a osobnostních charakteristik) neprokázaly[9], jiné byly z větší části bez pozitivních výsledků.[10][11] Nelze proto tyto teorie považovat za stoprocentně spolehlivé.

Toxoplasma gondii (Nicolle et Manceaux, 1908) je vnitrobuněčný parazitický prvok, vícehostitelská kokcidie, která parazituje v buňkách člověka i zvířat. Jejím definitivním hostitelem jsou kočkovité šelmy, mezihostitelem se může stát většina teplokrevných živočichů včetně člověka. Způsobuje toxoplazmózu, u těhotných žen hrozí při infekci tímto prvokem narození postiženého dítěte. U HIV pacientů může způsobit akutní zánět mozku. Rovněž může způsobit aborty u ovcí a koz.

Toxoplasma er en slægt af parasitiske protozoer. Arten Toxoplasma gondii forårsager sygdommen toxoplasmose også kaldet haresyge. Den har tre udviklingsstadier, oocyster, vævscyster og tachyzoiter. Parasitten er udbredt i hele verden undtagen i de arktiske egne og kan smitte de fleste fugle og pattedyr, inklusiv mennesker. De formerer sig kønsløst i forskellige vævstyper. Hovedværten for Toxoplasma gondii er katten, hvor parasittens seksuelle stadier forekommer.

Katten er hovedvært, og er den eneste dyreart der udskiller oocyster med fæces. Oocysterne er meget resistente, og kan findes spredt i omgivelserne, f.eks. i jorden, sandkasser, og græs. Oocysterne kan også findes indenfor i huset eller i stalden.

Når en kat bliver inficeret, udskiller den op til 10 millioner oocyster over en periode på 2 uger. Oocysterne bliver infektiøse 1-5 dage efter udskillelsen. De kan spredes med overfladevand og kan overleve i op til et år. Dette kan forklare hvorfor kontakt med jord og vand udgør en større smitterisiko end kontakt med katte.

Oocysterne i kattens tarmsystem er det seksuelle stadie hos Toxoplasma gondii. De hunlige kønsceller er halvrunde og hver celle har en centralt placeret kerne. De hanlige kønsceller er ægge- eller elipseformede og bruger deres flageller til at svømme hen til de modne hunlige kønsceller, penetrere dem og dermed lave en zygote. Efter befrugtning dannes en oocyst-væg omkring parasitten og toxoplasma-ægget er dannet. I hver oocyst (toxoplasma-æg) findes to sporozyster, og i hvert sporocyst findes 4 sporozoiter. Sporozoiterne minder strukturelt meget om tachyzoiterne, men har nogle lidt andre organeller.

Hovedsmittekilden i vores del af verden er vævscyster i muskulatur og organer fra tidligere Toxoplasma smittede dyr, specielt fra svin, lam og vildt, og i mindre grad fra oksekød og kyllinger. Cysterne findes i størst mængde i ikke skeletmuskulatur. Indtagelse af råt/ikke gennemstegt kød er en væsentlig risokofaktor. Cysterne bliver destrueret ved opvarmning til mere end 66 °C i 3 min, og ved nedfrysning til -20 °C. Rygning, saltning og bestråling vil også destruere cysterne. Vævcysten sidder inde i muskelcellen, og vokser i takt med at parasitten, som i dette stadie hedder bradyzoit (brady = langsomt på græsk) deler sig ved aseksuel formering. Sidder de i hjernen, er de som oftes sfæriske og maximalt 70 µm i diameter, mens vævscyster i musklerne er aflange og op til 100 µm lange. Desuden findes cysterne også i andre former for væv, men dette er ikke helt så almindeligt. Hvis cysten bevares intakt, kan den opholde sig i værten hele dennes liv uden at forårsage betændelsestilstande.

I tachyzoite-stadiet formerer organismen sig hastigt i en hvilken som helst celle i en mellemvært, samt overflade væv der ikke sidder i tarmen hos den ægte vært. Tachyzoiten er halvmåneformet, og 2-6 µm lang. Selvom tachyzoiter kan glide, bøje og rotere, har den ingen synlige midler til at sætte sig i bevægelse, som f.eks. cilia eller flageller.

Tachyzoiter trænger ind i værtscellen ved aktivt at gennembore dennes plasmalemma. Når parasitten er inde i cellen, bliver den æggeformet, og omgives af en parasittisk væskefyldt celleblære, som tilsyneladende skabes af både parasitten selv og værtscellen. Herefter ligger tachyzoiten i dvale i en periode før den begynder at formere sig aseksuelt gentagende gange, indtil værtscellen ikke længere har plads til alle parasitterne, hvorved den sprænges. Længden af dvaleperioden, hastigheden af formeringen samt størrelsen af tilvæksten af de enkelte tachyzoiter afhænger både af hvilken art Toxoplasma der er tale om, samt typen af vært.

Tachyzoiten adskiller sig rent strukturelt kun fra bradyzoiten ved det at cellekernen sidder centralt i cellen, mens den i bradyzoiten sidder forskudt mod bagenden. Med hensyn til livscykus, er bradyzoitens dvaleperiode før den udvikles til ooyster efter indtagelse af katten kortere (3-10 dage) end hvis katten indtager tachyzoiter (≥14 dage).

Hos voksne er toxoplasmose sjældent alvorligt,[kilde mangler] men angribes gravide kvinder, kan parasitten overføres til fosteret. Parasitten er i nogle tilfælde årsag til dødfødte eller misdannede børn, der eventuelt får en begrænset levetid, bliver blinde eller hjerneskadede.[kilde mangler]

I Danmark er der set en sammenhæng mellem toxoplasmose hos kvinder og en omkring 50% øgning i selvmordsforsøg.[1] Man har også konstateret en øget risiko for involvering i færdselsuheld hos inficerede personer.[2]

Da parasitten er ret udbredt, bør kvinder, der enten er gravide eller planlægger at blive det i nær fremtid, ikke rengøre kattebakker, slagte og istandgøre vildt eller arbejde med dissektion af dyr.[kilde mangler]

Der er mange ideer om hvordan toxoplasmose påvirker værtsdyret. Nogle forskere har vist at rotter der er inficeret med Toxoplasma bliver påvirket af parasitten på en måde der gør dem tiltrukket af katte, hvilket jo er meget belejligt for parasitten som gerne vil have sit værtsdyr ædt af en kat, så den selv får mulighed for at formere sig.[3] Andre forskere har trukket paralleller mellem toxoplasmose og skizofreni, og andre igen har forsøgt påvist en sammenhæng mellem infektionen og antallet af fødte drengebørn, som i følge forskerne stiger i grupper af inficerede. I dyr er der evidens for at både oprættede svin[4] og vildsvin[5] i Danmark kan være inficeret med T. gondii.

Toxoplasma er en slægt af parasitiske protozoer. Arten Toxoplasma gondii forårsager sygdommen toxoplasmose også kaldet haresyge. Den har tre udviklingsstadier, oocyster, vævscyster og tachyzoiter. Parasitten er udbredt i hele verden undtagen i de arktiske egne og kan smitte de fleste fugle og pattedyr, inklusiv mennesker. De formerer sig kønsløst i forskellige vævstyper. Hovedværten for Toxoplasma gondii er katten, hvor parasittens seksuelle stadier forekommer.

Toxoplasma gondii (von altgriechisch τόξον tóxon ‚Bogen‘ und πλάσμα plásma ‚Gebilde‘) ist ein bogenförmiges Protozoon mit parasitischer Lebensweise. Sein Endwirt sind Katzen, als Zwischenwirt dienen andere Wirbeltiere. Es ist der einzige bekannte Vertreter der Gattung Toxoplasma. Der Parasit ist Verursacher der Toxoplasmose und nahe verwandt mit Plasmodium, dem Erreger der Malaria, und mit Cryptosporidium.

Toxoplasma gondii wurde erstmals 1907 in Tunesien als Parasit im Gundi (Ctenodactylus gundi) entdeckt und als Angehöriger der Apicomplexa identifiziert.[1] Aufgrund der Halbmondform wurde es von den Entdeckern Charles Nicolle und Louis Manceaux als Toxoplasma (griechisch toxon, Bogen; plasma, Gebilde) und aufgrund des Wirtstieres als Toxoplasma gondii benannt. Erst viel später konnte es auch beim Menschen als Krankheitserreger gefunden werden, die von ihm ausgelöste Krankheit wurde Toxoplasmose genannt. 1948 entwickelten Sabin und Feldman einen serologischen Test auf der Basis von Antikörpern, den sie Dye-Test nannten.[2] Mit Hilfe dieser Methode konnte festgestellt werden, dass Toxoplasma gondii weltweit verbreitet ist und beim Menschen sehr häufig vorkommt.

Der Parasit ist weltweit verbreitet, die Bevölkerung weist eine hohe Durchseuchung auf, da die Infektion meist ohne Symptome verläuft.[3]

Bei 50 % der Bevölkerung in Deutschland wurden Antikörper nachgewiesen. Mit zunehmendem Alter steigt die Infektionswahrscheinlichkeit an. Bei über 70-Jährigen liegt sie bei über 70 %.[4]

Toxoplasma gondii unterscheidet sich je nach Stadium sowohl in der Form als auch in der Größe. Die Zellen der freien und infektiösen Form sind in flüssigen Medien oder Frischpräparaten bogenförmig und erreichen Größen von zwei bis fünf Mikrometern. Betrachtet man sie in Gewebeproben oder fixierten Schnitten, erscheinen sie dagegen eiförmig oval. Außerdem können sie sowohl einzeln als auch zu mehreren in so genannten Pseudozysten im Gewebe vorkommen.

Die Oozysten messen bis zu 11 Mikrometer, die Gewebszysten bis zu 300 Mikrometer. Es bilden sich zwei verschiedene Populationen von Sporozoiten, die Tachyzoiten bilden sich nach dem Eindringen in den Zwischenwirt und vermehren sich dort rapide. Später treten Bradyzoiten auf, deren Vermehrung stark verlangsamt ist. Strukturell unterscheiden sich diese beiden Formen nicht.

Die Oozysten werden vom Endwirt (Katzenartige) mit dem Kot ausgeschieden und gelangen so in den Zwischenwirt. Sie enthalten zwei Sporozysten mit je vier Sporozoiten. Sie können sehr lange (bis fünf Jahre) infektiös bleiben und überstehen Frost, sind jedoch nicht sehr hitzeresistent. Im Zwischenwirt (Wirbeltiere, z. B. Vögel) schlüpfen die Sporozysten, diese dringen nun aktiv in kernhaltige Zellen des Zwischenwirtes ein (vor allem Lymphknoten, Retikuloendotheliales System). Nun setzt eine Vermehrung durch ungeschlechtliche Teilung ein, bei der sich zwei Tochterzellen von der Mutterzelle ablösen, wobei die Mutterzelle sich auflöst (Endodyogenie). Dieser Vorgang läuft so lange ab, bis die Wirtszelle komplett ausgefüllt ist und aufplatzt, so dass die Tachyzoiten (griechisch tachys = schnell) frei werden. Dieser Vorgang wiederholt sich alle 6 Stunden. Die Tachyzoiten breiten sich nach der Freisetzung im Blut aus und gehen so auch über die Plazenta ins Blut der Nachkommen über. Nachdem die Wirtsabwehr eingesetzt hat, verlangsamt sich die Teilungsdauer, und man spricht nun von Bradyzoiten (griech. bradys = langsam). Es bilden sich in den Zellen Gewebezysten, die vor allem in der Muskulatur, aber auch im Gehirn oder in der Netzhaut des Auges latent überdauern. In dieser Form werden sie wiederum von der Katze, die den Zwischenwirt frisst, aufgenommen. Die Bradyzoiten werden im Darm frei und dringen in die Epithelzellen ein. Dort findet eine Schizogonie (ungeschlechtliche Fortpflanzung) statt und/oder es werden Makrogamonten und Mikrogamonten gebildet. Die Makrogamonten bilden Makrogameten (vergleichbar mit einer Eizelle) aus, während ein Mikrogamont Mikrogameten erzeugt (vergleichbar mit Spermien). Der Makrogamet wird von einem Mikrogameten befruchtet, und es kommt zur Bildung einer Zygote (diploid), welche dann zu einer unsporulierten Oozyste reift. Diese wird mit dem Kot ausgeschieden und reift in der Außenwelt in 2 bis 4 Tagen unter Sauerstoffeinfluss zu infektionsfähigen sporulierten Oozysten heran. Sie ist bis zu 5 Jahre infektionsfähig. Falls die Oozysten von Katzen aufgenommen werden, so entwickeln sich Tachyzoiten, Bradyzoiten und Gewebezysten. Diese verbleiben jedoch nur zu einem geringen Teil im Gewebe und wandern in das Darmepithel der Katze ein, wo sie erneut durch Schizogonie und Gamogonie Oozysten ausbilden. Der Lebenszyklus wird in drei Phasen unterteilt, 1. in die extraintestinale Phase, 2. in die externe Phase und 3. in die enteroepitheliale Phase.

Beim Menschen ruft dieser Parasit die Krankheit Toxoplasmose hervor. Er kann T. gondii in beiden Formen aufnehmen, sowohl als Zysten in halb rohem Fleisch als auch als Schmierinfektion mit Katzenkot. Er übernimmt dann die Rolle des Zwischenwirtes, das heißt die Erreger durchdringen die Darmwand, um so in der Muskulatur, aber auch in anderen Organen Zysten zu bilden, die lebenslang überdauern. Die meisten Menschen machen irgendwann einmal diese Infektion durch, sie bleibt meistens ohne Symptome. Es kann einige Monate lang zu grippeähnlichen Beschwerden wie Fieber, Gelenk- und Muskelschmerzen und beispielsweise Lymphknotenschwellungen kommen.

Bei Nagetieren konnten durch Toxoplasma verursachte Verhaltensänderungen nachgewiesen werden. So verlieren infizierte Tiere ihre angeborene Scheu gegenüber dem Geruch von Katzen, was dem Lebenszyklus von Toxoplasma förderlich ist.[5] Bei Mäusen bleibt der Verlust der Scheu gegenüber dem Geruch von Katzenurin auch nach einer ausgeheilten Infektion mit T. gondii erhalten.[6] Bei mit T. gondii infizierten Ratten ist im limbischen System die Aktivität in den Regionen erhöht, die für die sexuelle Anziehung verantwortlich sind, wenn die Tiere dem Geruch von Katzenurin ausgesetzt werden. Dies wird als möglicher Mechanismus diskutiert, warum infizierte Nagetiere ihre Scheu vor Katzen verlieren.[7]

Beim Menschen werden durch Toxoplasmainfektionen möglicherweise verursachte Verhaltensänderungen immer wieder diskutiert.[3][8][9][10][11] Eine Infektion könnte beispielsweise die Risikobereitschaft erhöhen.[12]

Schwangere sollten kein Fleisch essen, das nicht durchgebraten ist, möglichst nicht mit Katzenkot in Berührung kommen und nicht im Garten arbeiten. Notfalls schützen Handschuhe oder Händewaschen vor den Mahlzeiten.[4] Es ist sinnvoll, dass eine andere Person das Katzenklo täglich reinigt, weil die Oozysten erst frühestens zwei Tage nach Ausscheidung infektiös werden.

Bis und mit 2015 existiert keine für Menschen zugelassene Impfung gegen Toxoplasma gondii.[13]

Bezüglich der Immunisierung von Schafen ist aber seit einiger Zeit ein Lebendimpfstoff mit Handelsnamen Toxovax (MSD Animal Health) verfügbar. Dieser bietet einen lebenslangen Schutz vor Toxoplasma gondii.[14]

Eine Infektion lässt sich normalerweise am leichtesten durch immunologische Testverfahren (ELISA, Immunfluoreszenztest, ISAGA) nachweisen, also Nachweis von spezifischen Antikörpern. Dabei sprechen IgM- Antikörper für eine frische Infektion, IgM- und IgG- Antikörper zusammen für eine Infektion innerhalb der letzten eineinhalb Jahre. Liegen sowohl IgG- als auch IgM-Antikörper vor, hilft ein sogenannter Aviditätstest beim Ausschluss einer frischen Infektion.

Es stehen auch molekularbiologische Untersuchungen (PCR) zur Verfügung. Sie eignen sich zur Untersuchung von Fruchtwasser zum Nachweis einer bereits erfolgten Übertragung auf das ungeborene Kind. Eine Schädigung des Kindes kann man durch Ultraschall diagnostizieren. Auch bei immungeschwächten Patienten eignet sich am ehesten die PCR oder Sichtbarmachung bereits entstandener größerer Läsionen mittels bildgebender Verfahren (CT, MRT).

T. gondii gehört zu den Infektionen, auf die man bei Schwangeren routinemäßig testen sollte, ähnlich wie Röteln, Syphilis, Hepatitis B, Chlamydien, HIV, eventuell Zytomegalie. Die Untersuchung ist in Deutschland jedoch nicht Bestandteil der normalen Schwangerenvorsorge. Wenn schon früher einmal eine Infektion auf T. gondii nachgewiesen wurde, geht davon keine Gefahr mehr aus. Das ungeborene Kind ist dann während der Schwangerschaft durch die mütterlichen Antikörper vor einer Infektion geschützt.

Die Diagnose kann sehr schwierig werden, wenn sie im Nachhinein bei einem Neugeborenen gestellt werden muss, das erst spät Krankheitszeichen zeigt (beispielsweise Erblindung durch Chorioretinitis).

Eine Erstinfektion mit T. gondii während der Schwangerschaft sollte mit Antibiotika behandelt werden. Ansonsten kann eine Behandlung sinnvoll sein, wenn der Patient Symptome zeigt. Bewährt hat sich die Kombination Pyrimethamin zusammen mit einem Sulfonamid oder Clindamycin. Vor der 18. Schwangerschaftswoche wird alternativ ein Makrolidantibiotikum, z. B. Spiramycin, verabreicht, da dieses – im Gegensatz zu erstgenannten – wahrscheinlich keine Fehlbildungen beim ungeborenen Kind auslöst. Allerdings ist man nicht sicher, wie wahrscheinlich eine Übertragung während der Frühschwangerschaft überhaupt ist. Eventuell sollte das Kind nach der Geburt noch einige Zeit nachbehandelt werden. Alles in allem kann eine Schädigung des Kindes durch diesen sehr häufigen Parasiten also meistens verhindert werden.

Toxoplasma gondii (von altgriechisch τόξον tóxon ‚Bogen‘ und πλάσμα plásma ‚Gebilde‘) ist ein bogenförmiges Protozoon mit parasitischer Lebensweise. Sein Endwirt sind Katzen, als Zwischenwirt dienen andere Wirbeltiere. Es ist der einzige bekannte Vertreter der Gattung Toxoplasma. Der Parasit ist Verursacher der Toxoplasmose und nahe verwandt mit Plasmodium, dem Erreger der Malaria, und mit Cryptosporidium.

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular, parasitic protozoan that causes the disease toxoplasmosis.[3]

Toxoplasma gondii ya iku spesies organisme sel tunggal (protozoa) kang urip minangka parasit.[3] Organisme iki sepisanan diidentifikasi déning Nicolle lan Manceaux.[4][5] Toxoplasma gondii nyebabaké toksoplasmosis, lelara kang bisa nyerang makhluk berdarah panas, kalebu manungsa. Kéwan Felidae kaya déné kucing kampung minangka inang definitif kang dadi panggonan T. gondii nindakaké réprodhuksi seksual. Lelara iki ora duwé tandha-tandha kang cetha. Uji TORCH bisa mangertèni anané infèksi lan lelara iki bisa diobati nganti pasièn mari.

Toxoplasma gondii ya iku spesies organisme sel tunggal (protozoa) kang urip minangka parasit. Organisme iki sepisanan diidentifikasi déning Nicolle lan Manceaux. Toxoplasma gondii nyebabaké toksoplasmosis, lelara kang bisa nyerang makhluk berdarah panas, kalebu manungsa. Kéwan Felidae kaya déné kucing kampung minangka inang definitif kang dadi panggonan T. gondii nindakaké réprodhuksi seksual. Lelara iki ora duwé tandha-tandha kang cetha. Uji TORCH bisa mangertèni anané infèksi lan lelara iki bisa diobati nganti pasièn mari.

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular, parasitic protozoan that causes the disease toxoplasmosis.

టాక్సోప్లాస్మా (లాటిన్ Toxoplasma ఒక వ్యాధి కారక జీవుల ప్రజాతి.[1] వీనికి ప్రాథమిక అతిధేయి పిల్లి అయినా పక్షులు, క్షీరదాల వంటి చాలా రకాల జంతువులకు సంక్రమిస్తుంది.[2] వీని వలన కలిగే వ్యాధిని టాక్సోప్లాస్మోసిస్ (Toxoplasmosis) అంటారు.

Al Toxoplàśma góndi (nóm sientìfic “Toxoplasma gondii”) 'l è 'n parasìta protozoo prutìsta dal gat (òspit definitìṿ) e 'd atri bèsti a sangṿ cald cuma i mamìfar (sórag, nimài e via dascurénd), gl'uśèi e 'l óm ch'al pōl dvintàr al sò òspit intermèdi quànd al s bèca la Toxoplaśmóśi. Anc al gat al pōl śugàr al rōl d'l òspit intermèdi cumpàgn a chi àtar mamìfar s'al magna di oocìsti stramnàdi in dla mèrda invéci che dal cìsti da la carna dal sò vitmi.

Al parasìta al fà part dla famìja di Sarcocystidae e 'l è la sōla spécie dal gènar Toxoplasma ch'a sa cgnós a 'l dè 'd incō.

Al cicclo 'd vita dal Toxoplàśma góndi al taca quànd al gat al s infèta magnànd dla carna cun dèntar dal cisti. In dal stómag i sûg gàstric i dìsfan la cisti librànd acsè 'l parasìta ch'al pasa in dal sò budèli in dua dvintâ adûlt al s multìplica cun la riprudusiòṅ sesuàla faghénd di oocìsti ch'i miśùran 10x12 micron e ch'i vènan cagàdi via c'n i pét. Qvést a sucéd sōl p'r una o dū stmani dòp l'infesiòṅ. Fóra dal còrp dal gat i gh métan dū dè a maduràr e dvintàr bòni p'r infetàr 'l òspit intermèdi.

Quànd chi lò al i manda śò catànd-i in gir o magnànd dla carna infèta (cun dal cisti dèntar cum a pōl far 'l óm) al s bèca 'l mâł. I parasìta i śbuśìs'n al budèli e i pàs'n in dal sangṿ ch'al gh sarvìs par rivàr dapartùt, specialmènt in dal cèluli di tesû in dua i s multìplican dvidénd-'s in dū e pò in quàt'r e in òt in fiṅ tant ch'la cèlula la sćiòpa.

L'è la prima faś dal mâł in dua, spétand ch'al sistéma imunitàri al faga gl'anticòrp, a pōl vgnir la févra, sèns cuma 'd “òs śbragâ”, giàdli grôsi acsè cuma 'l fégat e la milsa, stufìśia, mâł ad tèsta e a la góla. S'al parasìta al riva a i òć a s pōl anc armàgn'r òrub parchè la rétina la ténd a far infesiòṅ anc dòp di an [1]. I sugèt ch'i gh'aṅ al diféśi débuli, parchè p'r eśèmpi i aṅ fat di trapiànt, parchè i gh'àṅ 'l AIDS o i èṅ di vèć tarulî, i rìsćian ad bcar-as di brut mâi a 'l sarvèl o 'd murìr. Dòp soquànti stmani però al sistéma imunitàri al gh la cava a cumbàt'r al parasìta (secónda faś dal mâł) ch'al fà più fadìga a multiplicàr-as e par prutéś'r-as al s sèra dènt'r a na cisti in di mùscui o in dal sarvèl. In gènar la Toxoplaśmóśi in d'l óm la và avànti acsè par di an faghénd pôc dan. S'a s mala na dóna ch'la gh'à 'd avér fiōl 'l è invéci 'n bèl prubléma parchè 'l parasìta al pōl tacàr la cretinìśia a 'l putèṅ o cauśàr 'n abòrt [2].

Quànd al gat al magna la carna infèta al dvènta 'l sò òspit definitìṿ srand al sérć. I padròṅ di gat i gh'aṅ da pulìr da spés l'altéra in dua al sò bèsti i càgan, lavànd-'s anc al maṅ cum a ś dév p'r a n andàr minga in a risć ad malàr-as dla toxoplaśmóśi. Adès p'r al fat ch'i gat dumèstic i màgnan praticamènt sèmpar dal magnàr cumprâ cuma qvél in dal scatuléti o in dal busti, al perìcul al s è arbasâ dimóndi spustànd-'s invéci in di gat salvàdag.

A s è vist pò ch'i sórag, quànd i ciàp'n al parasìta, i dvèntan sfaciâ e i n gh'aṅ piò paùra di gat tant ch'in scàpan minga via quànd i sèntan 'l udōr dla sò pisa [3]. A sucéd acsè ch'al Toxoplàśma góndi al fà in manéra ad pasàr facimènt a 'l sò stadi finàł parchè p'r al gat 'l è dimóndi fàcil magnàr di sórag imbambî. In di óm invéci al parasìta al pōl far dvintàr mat o schisufrènig i malâ [4] o parsuàd'r al dóni a cupàr-as [5].

P'r arbasàr al risć ad ciapàr al parasìta a gh'è sèmpar da cōśar bèṅ la carna e da lavàr-as bèṅ dòp ès'r andâ fóra parchè a s pōl tucàr quèl in dua i aṅ cagâ dal bèsti malàdi librànd acsè di oocìsti dal Toxoplàśma góndi.

Al Toxoplàśma góndi (nóm sientìfic “Toxoplasma gondii”) 'l è 'n parasìta protozoo prutìsta dal gat (òspit definitìṿ) e 'd atri bèsti a sangṿ cald cuma i mamìfar (sórag, nimài e via dascurénd), gl'uśèi e 'l óm ch'al pōl dvintàr al sò òspit intermèdi quànd al s bèca la Toxoplaśmóśi. Anc al gat al pōl śugàr al rōl d'l òspit intermèdi cumpàgn a chi àtar mamìfar s'al magna di oocìsti stramnàdi in dla mèrda invéci che dal cìsti da la carna dal sò vitmi.

Al parasìta al fà part dla famìja di Sarcocystidae e 'l è la sōla spécie dal gènar Toxoplasma ch'a sa cgnós a 'l dè 'd incō.

Al cicclo 'd vita dal Toxoplàśma góndi al taca quànd al gat al s infèta magnànd dla carna cun dèntar dal cisti. In dal stómag i sûg gàstric i dìsfan la cisti librànd acsè 'l parasìta ch'al pasa in dal sò budèli in dua dvintâ adûlt al s multìplica cun la riprudusiòṅ sesuàla faghénd di oocìsti ch'i miśùran 10x12 micron e ch'i vènan cagàdi via c'n i pét. Qvést a sucéd sōl p'r una o dū stmani dòp l'infesiòṅ. Fóra dal còrp dal gat i gh métan dū dè a maduràr e dvintàr bòni p'r infetàr 'l òspit intermèdi.

Quànd chi lò al i manda śò catànd-i in gir o magnànd dla carna infèta (cun dal cisti dèntar cum a pōl far 'l óm) al s bèca 'l mâł. I parasìta i śbuśìs'n al budèli e i pàs'n in dal sangṿ ch'al gh sarvìs par rivàr dapartùt, specialmènt in dal cèluli di tesû in dua i s multìplican dvidénd-'s in dū e pò in quàt'r e in òt in fiṅ tant ch'la cèlula la sćiòpa.

L'è la prima faś dal mâł in dua, spétand ch'al sistéma imunitàri al faga gl'anticòrp, a pōl vgnir la févra, sèns cuma 'd “òs śbragâ”, giàdli grôsi acsè cuma 'l fégat e la milsa, stufìśia, mâł ad tèsta e a la góla. S'al parasìta al riva a i òć a s pōl anc armàgn'r òrub parchè la rétina la ténd a far infesiòṅ anc dòp di an . I sugèt ch'i gh'aṅ al diféśi débuli, parchè p'r eśèmpi i aṅ fat di trapiànt, parchè i gh'àṅ 'l AIDS o i èṅ di vèć tarulî, i rìsćian ad bcar-as di brut mâi a 'l sarvèl o 'd murìr. Dòp soquànti stmani però al sistéma imunitàri al gh la cava a cumbàt'r al parasìta (secónda faś dal mâł) ch'al fà più fadìga a multiplicàr-as e par prutéś'r-as al s sèra dènt'r a na cisti in di mùscui o in dal sarvèl. In gènar la Toxoplaśmóśi in d'l óm la và avànti acsè par di an faghénd pôc dan. S'a s mala na dóna ch'la gh'à 'd avér fiōl 'l è invéci 'n bèl prubléma parchè 'l parasìta al pōl tacàr la cretinìśia a 'l putèṅ o cauśàr 'n abòrt .

Quànd al gat al magna la carna infèta al dvènta 'l sò òspit definitìṿ srand al sérć. I padròṅ di gat i gh'aṅ da pulìr da spés l'altéra in dua al sò bèsti i càgan, lavànd-'s anc al maṅ cum a ś dév p'r a n andàr minga in a risć ad malàr-as dla toxoplaśmóśi. Adès p'r al fat ch'i gat dumèstic i màgnan praticamènt sèmpar dal magnàr cumprâ cuma qvél in dal scatuléti o in dal busti, al perìcul al s è arbasâ dimóndi spustànd-'s invéci in di gat salvàdag.

A s è vist pò ch'i sórag, quànd i ciàp'n al parasìta, i dvèntan sfaciâ e i n gh'aṅ piò paùra di gat tant ch'in scàpan minga via quànd i sèntan 'l udōr dla sò pisa . A sucéd acsè ch'al Toxoplàśma góndi al fà in manéra ad pasàr facimènt a 'l sò stadi finàł parchè p'r al gat 'l è dimóndi fàcil magnàr di sórag imbambî. In di óm invéci al parasìta al pōl far dvintàr mat o schisufrènig i malâ o parsuàd'r al dóni a cupàr-as .

P'r arbasàr al risć ad ciapàr al parasìta a gh'è sèmpar da cōśar bèṅ la carna e da lavàr-as bèṅ dòp ès'r andâ fóra parchè a s pōl tucàr quèl in dua i aṅ cagâ dal bèsti malàdi librànd acsè di oocìsti dal Toxoplàśma góndi.

Toxoplasma gondii (/ˈtɒksəˌplæzmə ˈɡɒndi.aɪ, -iː/) is a parasitic protozoan (specifically an apicomplexan) that causes toxoplasmosis.[3] Found worldwide, T. gondii is capable of infecting virtually all warm-blooded animals,[4]: 1 but felids are the only known definitive hosts in which the parasite may undergo sexual reproduction.[5][6]

In rodents, T. gondii alters behavior in ways that increase the rodents' chances of being preyed upon by felids.[7][8][9] Support for this "manipulation hypothesis" stems from studies showing that T. gondii-infected rats have a decreased aversion to cat urine while infection in mice lowers general anxiety, increases explorative behaviors and increases a loss of aversion to predators in general.[7][10] Because cats are one of the only hosts within which T. gondii can sexually reproduce, such behavioral manipulations are thought to be evolutionary adaptations that increase the parasite's reproductive success since rodents that do not avoid cat habitations will more likely become cat prey.[7] The primary mechanisms of T. gondii–induced behavioral changes in rodents occur through epigenetic remodeling in neurons that govern the relevant behaviors (e.g. hypomethylation of arginine vasopressin-related genes in the medial amygdala, which greatly decrease predator aversion).[11][12]

In humans, particularly infants and those with weakened immunity, T. gondii infection is generally asymptomatic but may lead to a serious case of toxoplasmosis.[13][4] T. gondii can initially cause mild, flu-like symptoms in the first few weeks following exposure, but otherwise, healthy human adults are asymptomatic.[14][13][4] This asymptomatic state of infection is referred to as a latent infection, and it has been associated with numerous subtle behavioral, psychiatric, and personality alterations in humans.[14][15][16] Behavioral changes observed between infected and non-infected humans include a decreased aversion to cat urine (but with divergent trajectories by gender) and an increased risk of several psychiatric disorders – particularly schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Preliminary evidence has suggested that T. gondii infection may induce some of the same alterations in the human brain as those observed in rodents.[17][18][9][19][20][21] Many of these associations have been strongly debated and newer studies have found them to be weak concluding:[22]

On the whole, there was little evidence that T. gondii was related to increased risk of psychiatric disorder, poor impulse control, personality aberrations, or neurocognitive impairment.

T. gondii is one of the most common parasites in developed countries;[23][24] serological studies estimate that up to 50% of the global population has been exposed to, and may be chronically infected with, T. gondii; although infection rates differ significantly from country to country.[14][25] Estimates have shown the highest IgG seroprevalence to be in Ethiopia, at 64.2%, as of 2018.[26]

T. gondii contains organelles called rhoptries and micronemes, as well as other organelles.

The lifecycle of T. gondii may be broadly summarized into two components: a sexual component that occurs only within cats (felids, wild or domestic), and an asexual component that can occur within virtually all warm-blooded animals, including humans, cats, and birds.[27]: 2 Because T. gondii can sexually reproduce only within cats, cats are therefore the definitive host of T. gondii. All other hosts – in which only asexual reproduction can occur – are intermediate hosts.

When a feline is infected with T. gondii (e.g. by consuming an infected mouse carrying the parasite's tissue cysts), the parasite survives passage through the stomach, eventually infecting epithelial cells of the cat's small intestine.[27]: 39 Inside these intestinal cells, the parasites undergo sexual development and reproduction, producing millions of thick-walled, zygote-containing cysts known as oocysts. Felines are the only definitive host because they lack expression of the enzyme delta-6-desaturase (D6D) in their intestine. This enzyme converts linoleic acid; the absence of expression allows systemic linoleic acid accumulation. Recent findings showed that this excess of linoleic acid is essential for T. gondii sexual reproduction.[6]

Infected epithelial cells eventually rupture and release oocysts into the intestinal lumen, whereupon they are shed in the cat's feces.[4]: 22 Oocysts can then spread to soil, water, food, or anything potentially contaminated with the feces. Highly resilient, oocysts can survive and remain infective for many months in cold and dry climates.[28]

Ingestion of oocysts by humans or other warm-blooded animals is one of the common routes of infection.[29] Humans can be exposed to oocysts by, for example, consuming unwashed vegetables or contaminated water, or by handling the feces (litter) of an infected cat.[27]: 2 [30] Although cats can also be infected by ingesting oocysts, they are much less sensitive to oocyst infection than are intermediate hosts.[31][4]: 107

Intermediate hosts found include pigs, chickens, goats, sheep[27]: 2 and Macropus rufus by Moré et al. 2010.[32]: 162 Cattle and horses are resistant and thought to be incapable of significant infection.[27]: 11 T. gondii is considered to have three stages of infection; the tachyzoite stage of rapid division, the bradyzoite stage of slow division within tissue cysts, and the oocyst environmental stage.[33] Tachyzoites are also known as "tachyzoic merozoites" and bradyzoites as "bradyzoic merozoites".[34] When an oocyst or tissue cyst is ingested by a human or other warm-blooded animal, the resilient cyst wall is dissolved by proteolytic enzymes in the stomach and small intestine, freeing sporozoites from within the oocyst.[29][33] The parasites first invade cells in and surrounding the intestinal epithelium, and inside these cells, the parasites differentiate into tachyzoites, the motile and quickly multiplying cellular stage of T. gondii.[27]: 39 Tissue cysts in tissues such as brain and muscle tissue, form about 7–10 days after initial infection.[33] Although severe infection of M. rufus has been observed it is unknown whether this is common.[32]

Inside host cells, the tachyzoites replicate inside specialized vacuoles (called the parasitophorous vacuoles) created from host cell membrane during invasion into the cell.[27]: 23–39 Tachyzoites multiply inside this vacuole until the host cell dies and ruptures, releasing and spreading the tachyzoites via the bloodstream to all organs and tissues of the body, including the brain.[27]: 39–40

The parasite can be easily grown in monolayers of mammalian cells maintained in vitro in tissue culture. It readily invades and multiplies in a wide variety of fibroblast and monocyte cell lines. In infected cultures, the parasite rapidly multiplies and thousands of tachyzoites break out of infected cells and enter adjacent cells, destroying the monolayer in due course. New monolayers can then be infected using a drop of this infected culture fluid and the parasite indefinitely maintained without the need of animals.

Following the initial period of infection characterized by tachyzoite proliferation throughout the body, pressure from the host's immune system causes T. gondii tachyzoites to convert into bradyzoites, the semidormant, slowly dividing cellular stage of the parasite.[35] Inside host cells, clusters of these bradyzoites are known as tissue cysts. The cyst wall is formed by the parasitophorous vacuole membrane.[27]: 343 Although bradyzoite-containing tissue cysts can form in virtually any organ, tissue cysts predominantly form and persist in the brain, the eyes, and striated muscle (including the heart).[27]: 343 However, specific tissue tropisms can vary between intermediate host species; in pigs, the majority of tissue cysts are found in muscle tissue, whereas in mice, the majority of cysts are found in the brain.[27]: 41

Cysts usually range in size between five and 50 µm in diameter,[36] (with 50 µm being about two-thirds the width of the average human hair).[37]

Consumption of tissue cysts in meat is one of the primary means of T. gondii infection, both for humans and for meat-eating, warm-blooded animals.[27]: 3 Humans consume tissue cysts when eating raw or undercooked meat (particularly pork and lamb).[38] Tissue cyst consumption is also the primary means by which cats are infected.[4]: 46

An exhibit at the San Diego Natural History Museum states urban runoff with cat feces transports Toxoplasma gondii into the ocean, which can kill sea otters.[39]

Tissue cysts can be maintained in host tissue for the lifetime of the animal.[27]: 580 However, the perpetual presence of cysts appears to be due to a periodic process of cyst rupturing and re-encysting, rather than a perpetual lifespan of individual cysts or bradyzoites.[27]: 580 At any given time in a chronically infected host, a very small percentage of cysts are rupturing,[27]: 45 although the exact cause of this tissue cyst rupture is, as of 2010, not yet known.[4]: 47

Theoretically, T. gondii can be passed between intermediate hosts indefinitely via a cycle of consumption of tissue cysts in meat. However, the parasite's lifecycle begins and completes only when the parasite is passed to a feline host, the only host within which the parasite can again undergo sexual development and reproduction.[29]

In 2006, researchers reviewed evidence that T. gondii has an unusual population structure dominated by three clonal lineages called Types I, II and III that occur in North America and Europe, despite the occurrence of a sexual phase in its life cycle. They estimated that a common ancestor existed about 10,000 years ago.[40] Authors of a subsequent and larger study on 196 isolates from diverse sources including T. gondii in the bald eagle, gray wolf, Arctic fox and sea otter, also found that T. gondii strains infecting North American wildlife have limited genetic diversity with the occurrence of only a few major clonal types. They found that 85% of strains in North America were of one of three widespread genotypes II, III and Type 12. Thus T. gondii has retained the capability for sex in North America over many generations, producing largely clonal populations, and matings have generated little genetic diversity.[41]

During different periods of its life cycle, individual parasites convert into various cellular stages, with each stage characterized by a distinct cellular morphology, biochemistry, and behavior. These stages include the tachyzoites, merozoites, bradyzoites (found in tissue cysts), and sporozoites (found in oocysts).

Some stages are motile and some calcium-dependent protein kinases (TgCDPKs) are involved in this parasite's motility.[42][43] Gaji et al. 2015 find TgCDPK3 is required to begin the action of motility because it phosphorylates T. gondii's myosin A (TgMYOA).[42][43] TgCDPK3 is the functional orthologue of CDPK1 in this parasite.[43]

Motile, and quickly multiplying, tachyzoites are responsible for expanding the population of the parasite in the host.[44][27]: 19 When a host consumes a tissue cyst (containing bradyzoites) or an oocyst (containing sporozoites), the bradyzoites or sporozoites stage-convert into tachyzoites upon infecting the intestinal epithelium of the host.[27]: 359 During the initial acute period of infection, tachyzoites spread throughout the body via the blood stream.[27]: 39–40 During the later, latent (chronic) stages of infection, tachyzoites stage-convert to bradyzoites to form tissue cysts.

Like tachyzoites, merozoites divide quickly, and are responsible for expanding the population of the parasite inside the cat's intestine before sexual reproduction.[27]: 19 When a feline definitive host consumes a tissue cyst (containing bradyzoites), bradyzoites convert into merozoites inside intestinal epithelial cells. Following a brief period of rapid population growth in the intestinal epithelium, merozoites convert into the noninfectious sexual stages of the parasite to undergo sexual reproduction, eventually resulting in zygote-containing oocysts.[27]: 306

Bradyzoites are the slowly dividing stage of the parasite that make up tissue cysts. When an uninfected host consumes a tissue cyst, bradyzoites released from the cyst infect intestinal epithelial cells before converting to the proliferative tachyzoite stage.[27]: 359 Following the initial period of proliferation throughout the host body, tachyzoites then convert back to bradyzoites, which reproduce inside host cells to form tissue cysts in the new host.

Sporozoites are the stage of the parasite residing within oocysts. When a human or other warm-blooded host consumes an oocyst, sporozoites are released from it, infecting epithelial cells before converting to the proliferative tachyzoite stage.[27]: 359

Initially, a T. gondii infection stimulates production of IL-2 and IFN-γ by the innate immune system.[35] Continuous IFN-γ production is necessary for control of both acute and chronic T. gondii infection.[35] These two cytokines elicit a CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell mediated immune response.[35] Thus, T-cells play a central role in immunity against Toxoplasma infection. T-cells recognize Toxoplasma antigens that are presented to them by the body's own Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules. The specific genetic sequence of a given MHC molecule differs dramatically between individuals, which is why these molecules are involved in transplant rejection. Individuals carrying certain genetic sequences of MHC molecules are much more likely to be infected with Toxoplasma. One study of>1600 individuals found that Toxoplasma infection was especially common among people who expressed certain MHC alleles (HLA-B*08:01, HLA-C*04:01, HLA-DRB 03:01, HLA-DQA*05:01 and HLA-DQB*02:01).[45]

IL-12 is produced during T. gondii infection to activate natural killer (NK) cells.[35] Tryptophan is an essential amino acid for T. gondii, which it scavenges from host cells. IFN-γ induces the activation of indole-amine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), two enzymes that are responsible for the degradation of tryptophan.[46] Immune pressure eventually leads the parasite to form cysts that normally are deposited in the muscles and in the brain of the hosts.[35]

The IFN-γ-mediated activation of IDO and TDO is an evolutionary mechanism that serves to starve the parasite, but it can result in depletion of tryptophan in the brain of the host. IDO and TDO degrade tryptophan to N-formylkynurenine. Administration of L-kynurenine is capable of inducing depressive-like behavior in mice.[46] T. gondii infection has been demonstrated to increase the levels of kynurenic acid (KYNA) in the brains of infected mice and in the brain of schizophrenic persons.[46] Low levels of tryptophan and serotonin in the brain were already associated with depression.[47]

The following have been identified as being risk factors for T. gondii infection in humans and warm-blooded animals:

A common argument in the debate about whether cat ownership is ethical involves the question of Toxoplasma gondii transmission to humans.[59] Even though "living in a household with a cat that used a litter box was strongly associated with infection,"[30] and that living with several kittens or any cat under one year of age has some significance,[49] several other studies claim to have shown that living in a household with a cat is not a significant risk factor for T. gondii infection.[50][60]

Specific vectors for transmission may also differ based on geographic location. "The seawater in California is thought to be contaminated by T. gondii oocysts that originate from cat feces, survive or bypass sewage treatment, and travel to the coast through river systems. T. gondii has been identified in a California mussel by polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing. In light of the potential presence of T. gondii, pregnant women and immunosuppressed persons should be aware of this potential risk associated with eating raw oysters, mussels, and clams.[49]

In warm-blooded animals, such as brown rats, sheep, and dogs, T. gondii has also been shown to be sexually transmitted.[61][62][63] Although T. gondii can infect, be transmitted by, and asexually reproduce within humans and virtually all other warm-blooded animals, the parasite can sexually reproduce only within the intestines of members of the cat family (felids).[29] Felids are therefore the definitive hosts of T. gondii; all other hosts (such as human or other mammals) are intermediate hosts.

The following precautions are recommended to prevent or greatly reduce the chances of becoming infected with T. gondii. This information has been adapted from the websites of United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention[64] and the Mayo Clinic.[65]

Basic food-handling safety practices can prevent or reduce the chances of becoming infected with T. gondii, such as washing unwashed fruits and vegetables, and avoiding raw or undercooked meat, poultry, and seafood. Other unsafe practices such as drinking unpasteurized milk or untreated water can increase odds of infection.[64] As T. gondii is commonly transmitted through ingesting microscopic cysts in the tissues of infected animals, meat that is not prepared to destroy these presents a risk of infection. Freezing meat for several days at subzero temperatures (0 °F or −18 °C) before cooking may break down all cysts, as they rarely survive these temperatures.[4]: 45 During cooking, whole cuts of red meat should be cooked to an internal temperature of at least 145 °F (63 °C). Medium rare meat is generally cooked between 130 and 140 °F (55 and 60 °C),[66] so cooking meat to at least medium is recommended. After cooking, a rest period of 3 min should be allowed before consumption. However, ground meat should be cooked to an internal temperature of at least 160 °F (71 °C) with no rest period. All poultry should be cooked to an internal temperature of at least 165 °F (74 °C). After cooking, a rest period of 3 min should be allowed before consumption.

Oocysts in cat feces take at least a day to sporulate (to become infectious after they are shed), so disposing of cat litter daily greatly reduces the chance of infectious oocysts developing. As these can spread and survive in the environment for months, humans should wear gloves when gardening or working with soil, and should wash their hands promptly after disposing of cat litter. These precautions apply to outdoor sandboxes/play sand pits, which should be covered when not in use. Cat feces should never be flushed down a toilet.

Pregnant women are at higher risk of transmitting the parasite to their unborn child and immunocompromised people of acquiring a lingering infection. Because of this, they should not change or handle cat litter boxes. Ideally, cats should be kept indoors and fed only food that has low to no risk of carrying oocysts, such as commercial cat food or well-cooked table food.

No approved human vaccine exists against Toxoplasma gondii.[67] Research on human vaccines is ongoing.[68]

For sheep, an approved live vaccine sold as Toxovax (from MSD Animal Health) provides lifetime protection.[69]

In humans, active toxoplasmosis can be treated with a combination of drugs such as pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine, plus folinic acid. Immune-compromised patients may need continuous treatment until/unless their immune system is restored.[70]

In many parts of the world, where there are high populations of feral cats, there is an increased risk to the native wildlife due to increased infection of Toxoplasma gondii. It has been found that the serum concentrations of T. gondii in the wildlife population were increased where there are high amounts of cat populations. This creates a dangerous environment for organisms that have not evolved in cohabitation with felines and their contributing parasites.[71]

Toxoplasmosis is one of the contributing factors toward mortality in southern sea otters, especially in areas where there is large urban run-off.[72] In their natural habitats, sea otters control sea urchin populations and, thus indirectly, control sea kelp forests. By enabling the growth of sea kelp, other marine populations are protected as well as CO2 emissions are reduced due to the kelp's ability to absorb atmospheric carbon.[73] An examination on 105 beachcast otters revealed that 38.1% had parasitic infections, and 28% of said infections had resulted in protozoal meningoencephalitis deaths.[72] Toxoplasma gondii was found to be the root cause in 16.2% of these deaths, while 6.7% of the deaths were due to a closely related protozoan parasite known as Sarcocystis neurona.[72]

Minks, being semiaquatic, are also susceptible to infection and being antibody-positive toward Toxoplasma gondii.[74] Minks can follow a similar diet as otters and feasts on crustaceans, fish, and invertebrates, thus the transmission route follows a similar pattern to otters. Because of the mink's ability to transverse land more frequently, and often seen as an invasive species itself, minks are a bigger threat in transporting T. gondii to other mammalian species, rather than otters who have a more restrictive breadth.[74]

Although under-studied, penguin populations, especially those that share an environment with the human population, are at-risk due to parasite infections, mainly Toxoplasmosis gondii. The main subspecies of penguins found to be infected by T. gondii include wild Magellanic and Galapagos penguins, as well as blue and African penguins in captivity.[75] In one study, 57 (43.2%) of 132 serum samples of Magellanic penguins were found to have T. gondii. The island that the penguin is located, Magdalena Island, is known to have no cat populations, but a very frequent human population, indicating the possibility of transmission.[75]

Examination of black-footed penguins with toxoplasmosis reveals hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, cranial hemorrhage, and necrotic kidneys (Ploeg, et al., 2011). Alveolar and hepatic tissue presents a high number of immune cells such as macrophages containing tachyzoites of T. gondii.[76] Histopathological features in other animals affected with toxoplasmosis had tachyzoites in eye structures such as the retina which lead to blindness.[76]