en

names in breadcrumbs

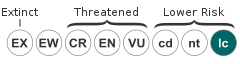

American alligators are listed as threatened by the federal government because they are similar in appearance to American crocodiles (Crocodylus acutus). American crocodiles are endangered and the government does not want hunters to confuse the two species. Hunting is allowed in some states, but is is heavily controlled.

US Federal List: threatened

CITES: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: lower risk - least concern

American alligators are the most vocal of all crocodilians, and communication begins early in life, while alligators are still in eggs. When they are ready to hatch, the young will make high pitched whining noises. Alligators commonly bellow and roar at one another. The bellow is loud and throaty, and can be heard from up to 165 yards away. Alligators also emit sounds called chumpfs. These are cough like purrs made during courting.

Other communication during mating season includes non-verbal forms such as lifting the head out of the water to show honorable intentions, headslapping by males as a sign of aggression to ward off intruders, and perhaps most notably, the virbrations, bubbles, and ripples seen in the water as a result of subaudible noises.

Communication Channels: tactile ; acoustic

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; vibrations

The temperature at which American alligator eggs develop determines their sex. Those eggs which are hatched in temperatures ranging from 90 to 93 degrees Fahrenheit turn out to be male, while those in temperatures from 82 to 86 degrees Fehrenheit end up being female. Intermediate temperature ranges have proven to yield a mix of both male and females. After hatching, alligators can grow rapidly, espectially during the first four years of life, averaging over 1 foot of growth for each year of life. Both sexes reach sexual maturity at around 6 feet in length, however, this occurs earlier in males because they reach this length sooner than females.

Development - Life Cycle: temperature sex determination

Since the alligator will feed on almost anything, they pose a threat to humans. In Florida, where there is the greatest alligator population, there were five deaths to alligator attacks from 1973 to 1990. Dogs and other pets are also sometimes killed. (University of Florida)

Alligators are hunted mostly for their skin, but also they are hunted for their meat. Today, there is a multimillion dollar industry in which alligators are raised in captivity for the production of their meat and skin. Also, alligators are a tourist attraction, especially in Florida.

Positive Impacts: food ; body parts are source of valuable material; ecotourism

American alligators have proven to be an important part of the environment, and therefor, are considered by many to be a "keystone" species. Not only do they control populations of prey species, they also create peat and "alligator holes" which are invaluable to other species. Red-bellied turtles, for example, incubates its own eggs in old alligator nests. Alligators also are good indicators of environmental factors, such as toxin levels. Increased levels of mercury have been found in recent blood samples.

Ecosystem Impact: creates habitat; keystone species

Alligators are basically carnivores, but they eat more than just meat, feeding on anything from sticks to fishing lures to aluminum cans. Mostly, they consume fish, turtles, snakes, and small mammals. When they are young they feed on insects, snails, and small fish.

Alligators hunt primarily in the water at night, snapping up small prey and swallowing it whole. Large prey are dragged under water, drowned and then devoured in pieces. Alligators have also been known to hold food in their mouth until it deteriorates enough to swallow. They also have a specialized valve in the throat called a glottis, which allows them to capture prey underwater.

With regards to hunting animals on land, alligators are usually considered idle hunters, waiting offshore for unsuspecting prey to drink at the water's edge. With this approach an alligator is likely to grab the drinking animal's head, slowly pulling it underwater until it drowns. In this way alligators exert minimal energy in capturing prey.

Animal Foods: birds; mammals; amphibians; reptiles; fish; eggs; insects; mollusks

Plant Foods: wood, bark, or stems

Primary Diet: carnivore (Eats terrestrial vertebrates, Piscivore )

American alligators are found from the southern Virginia-North Carolina border, along the Atlantic coast to Florida and along the Gulf of Mexico as far west as the Rio Grande in Texas.

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native )

American alligators are usually found in freshwater swamps, marshes, rivers, lakes, and occasionally, smaller bodies of water. It is believed that this preference for calm waters has to do with their swimming and breathing. In areas of protected water, an American alligator has only to keep its nasal disk above water to breath, whereas in rough water the snout must be at a steeper angle, making it more difficult to swim. They can also tolerate reasonable amounts of salinity, but only for short amounts of time due to their lack of buccal glands.

American alligators are also known to modify their enivironment by creating burrows. These are created using both snout and tail and are used for shelter and hibernation during freezing temperatures. If the water they live in dries out, alligators will swim or walk to other bodies of water, sometimes even taking shelter in swimming pools.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; tropical ; freshwater

Aquatic Biomes: lakes and ponds; rivers and streams; coastal ; brackish water

Wetlands: marsh ; swamp

Other Habitat Features: urban ; suburban ; agricultural

While there are currently no methods for determining the age of an alligator while still alive, it is known that those in the wild tend to live to between 35 and 50 year, while those in captive generally live longer, around 65-80 years. Factors which can lead to earlier mortality include successful predation early in life and hunting by humans.

Typical lifespan

Status: wild: 35 to 50 years.

Typical lifespan

Status: captivity: 65 to 80 years.

The average size for an adult female is just under 3 meters (9.8 feet), while the adult male usually falls between 4 and 4.5 meters (13 to 14.7 feet). American alligators reaching lengths of 5-6 meters (16 to 20 feet) have been reported in the past, but there have been no recent recordings equaling those lengths.

Legs of American alligators are characteristically short, though capable of carrying the animal at a gallop. The front legs have five toes while the back legs have only four. The snout of this alligator species is also distinct, being significantly broader for those in captive, mainly due to a difference in diet.

Nostrils at the end of the snout allow for breathing while the alligator is otherwise fully submerged beneath the water's surface. During times of hibernation, alligators keep these nostrils just above the water's surface, allowing the top part of the body to freeze in ice. The large fourth tooth in the lower jaw fits into a socket in the upper jaw and is not visible when the mouth is closed.

Both males and females have an "armored" body with a muscular flat tail, used in propelling the animal forward while swimming. The skin on their back is armored with embedded bony plates called osteoderms or scutes. Adult males and females have an olive brown or black color with a creamy white underside. The young can be distinguished from adults because they have bright yellow stripes on their tails. Eye color of American alligators is generally silverish.

Range length: 3 to 4.5 m.

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; heterothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: male larger

Average mass: 150000 g.

Average basal metabolic rate: 0.1539 W.

The first few years of a hatchlings life are the most dangerous, as anything that can eat a small alligator will. Snakes, wading birds, osprey, raccoons, otters, large bass, garfish, even larger alligators will feed upon young alligators. Once the alligator reaches about 4 feet, its only real predator is man. Extremely thick skin protected by bony plates called scutes prevent harm from most attacks. It is this skin, though, which attracts man to alligators. It is commercially used for the creation of wallets, purses, boots, and other textiles.

Known Predators:

Breeding takes place during the night, in shallow waters. Females usually initiate courtship during peak activity. When males (bulls) wish to attract females, they often roar or bellow, emmitting subaudible vibrations which can be seen by the bubbles and ripples they produce. Other courtship rituals include rubbing, touching, blowing bubbles, and vocalizing. It is also common for males to raise their heads out of the water, exposing their vulnerable necks as an expression of "good intentions". It is also quite common for both partners to try and push one another underwater in an attempt to judge eachothers strength.

Alligators are not monogamous, but rather, polygynous, which means one male may service up to ten or more females in his territory. This maximizes chances for successful breeding. Male alligators are territorial animals during the breeding season, and will defend their area against other male intruders, often displaying acts of headramming and sparring with open jaws.

Mating System: polygynous

Both males and females reach sexual maturity when they are about six feet long, a length attained at about 10 to 12 years, earlier for males than females. Courtship starts in April, with mating occuring in early May. After mating has taken place, the female builds a nest of vegetation. Then, around late June and early July, the female lays 35 to 50 eggs. Some females have been reported as laying up to 88 eggs. The eggs are then covered with the vegetation nest through the 65-day incubation period.

Towards the end of August, the young alligators begin to make high-pitched noises from inside of the egg. This lets the mother know that it is time to remove the nesting material, and the six to eight inch alligator is hatched. Newly hatched alligators live in small groups, call "pods." Eighty percent of young alligators fall victim to birds and raccoons. Other predators include bobcats, otters, snakes, large bass and larger alligators. Females have been known to aggressively defend their young during these first few months and, in some cases, years. Maturity is generally reached during the sixth year.

Breeding interval: American alligators breed once yearly.

Breeding season: Breeding occurs in early May, with egg laying occuring in late June and early July.

Range number of offspring: 35 to 88.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 10 to 12 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 10 to 12 years.

Key Reproductive Features: gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); oviparous

Males provide no parental care, and parental care by the female is limited to the first year of life. She is responsible for removing any vegetation covering the nest when her young are ready to hatch, and she will often bring them to water after hatching. During the first year or so she will defend her hatchlings from predators. After the first year, the female leaves her young to tend to new hatchlings of the next breeding season.

Parental Investment: pre-weaning/fledging (Protecting: Female)

The American Alligator is one of the largest North American reptiles. This species is native to the South-East United States, where it inhabits wetlands on the Atlantic coast from North Carolina to Florida, and in the Northern Gulf of Mexico west to Texas (Scott 2004). Alligators mostly inhabit marshes and swamps, but can also be found in rivers, streams, lakes, and ponds. Although they cannot survive in seawater, they do tolerate brackish water and venture into salt marshes, mangrove swamps, and other estuarine habitats (Scott 2004).

Adults and subadult alligators prey on a variety of aquatic organism including fish, crabs, snakes, turtles, mammals, birds, and other alligators (Jensen et al. 2008). Juveniles eat insects, amphibians, crayfish, molluscs and small fish (Jensen et al. 2008, Scott 2004).

Studies by Farmer and Sanders (2010) revealed that the lungs of the American Alligator--like those of birds, but unlike those of mammals--move air in only one direction during both inspiration and expiration through most of the tubular gas-exchanging bronchi (parabronchi). (In mammals, air moves tidally into and out of terminal gas-exchange structures, which are cul-de-sacs.) Given the phylogenetic relationship between crocodilians and birds, which are both archosaurs, Farmer and Sanders suggest that this air flow pattern may date back to the basal archosaurs of the Triassic and may have been present in their non-dinosaur descendants (phytosaurs, aetosaurs, rauisuchians, crocodylomorphs, and pterosaurs) as well as in dinosaurs, including birds (the avian dinosaurs).

Missisipi alliqatoru (lat. Alligator mississippiensis) və ya Amerikan alliqatoru — iki tanınmış alliqator növündən biridir. Şimali Amerikada yaşayır və Cənub-Şərqi ABŞ üçün endemik sayılır.

Bu canlı Texas ştatından Şimali Karolinaya qədər göllər, çaylar və sipər bataqlıqları kimi suyun təzə sularında yaşayan böyük bir sürünən timsahkimiləri təmsil edir. Bu, simpatrik, kəskin timsahdan daha geniş bir ağız, qaranlıq rəng və duzlu su üçün daha az tolerantlıq ilə fərqlənir, soyuducu suya qovuşdurmaqla kompensasiya edilir. Cinsin ikinci nümayəndəsi olan Çin alliqatoru ilə müqayisədə, Missisipi alliqatoru daha böyükdür.

Alliqatorlar — balıqlar, amfibiyalar, sürünənlər, quşlar və kiçik məməlilər yeyən yırtıcılardır. Yeni doğulanlar xüsusilə onurğasızlara qidalanırlar. Quraqlıq mövsümündə digər orqanizmlərə ev sahibliyi edən xüsusi çuxurların qazılması, sulak ekosistemində mühüm rol oynayırlar. Bir il ərzində, xüsusilə yetişdirmə mövsümündə alliqatorlar ərazini qeyd etmək və uyğun tərəfdaşları tapmaq üçün səslər səsləndirirlər. Kişilər qadınları cəlb etmək üçün infrousadan istifadə edirlər. Yumurta su bədəninin yaxınlığında sığınacaq yerində düşmüş bitki örtüyündən, çubuqdan və kirdən hazırlanmış bir yuvaya qoyulur. Gənc timsahlar bədənin ətrafındakı sarı xətlər ilə anadan olurlar və bir ilə qədər ananın himayəsi altında olurlar.

Tarixən olaraq, bir zamanda tənzimlənməmiş ovlanma sayıları çox təsirləndi və Amerika timsahı bir zamanlar nəsli kəsilməkdə olan bir növ olaraq sıralandı. Lakin növlərin qorunması üçün sonrakı səyləri onların sayını dramatik şəkildə artırmağa imkan verdi və indi Missisipi timsahı əsasən onun yaşıllığı səbəbindən minimal risklə qorunub saxlanılır. Timsahlar dəriləri və ətləri üçün fermalarda istehsal olunur. Bu heyvan üç Amerika ştatının rəsmi dövlət sürünənləridir: Florida, Luiziana və Mississippi.

Amerikan alliqatoru ilk dəfə 1801-ci ildə fransız zooloqu François Marie Daudin tərəfindən Crocodilus mississippiensis kimi təsnif olunmuşdur[2]. 1807-ci ildə Jorj Kyuve Alliqator cinsini təsvir etmiş və Çin alliqatoru birlikdə Amerika alliqatorunu müqayisə etmişdir. Alliqator ailəsi, Nil timsahı və ya qavial ilə müqayisədə, Amerika alliqatoru ilə daha yaxından əlaqəli olan timsah dəstəsinin bütün tükənmiş və müasir üzvlərini əhatə edir.

Bu ailənin üzvləri ilk dəfə təbaşir dövrünün sonunda göründü. Leidyosuchus Albertanın ən tanınmış cinsidir. Fosil alliqatorlari Avrasiya ərazisində aşkar edilmişdi ki, onlar bir zamanlar Şimali Atlantik və Berinq boğazının torpaq körpüsünü istifadə edərək, Şimali Amerika və Avrasiyanı təbaşir, paleogen və neogen dövründə birləşdirdilər. Alliqatorlar və kaymanlar Şimali Amerikada təbaşirin sonunda bölündü; sonuncu, Neogen dövründə Panama boğazının formalaşmasından əvvəl Paleogen dövründə Cənubi Amerikaya çatdı. Çin alliqatoru isə, ehtimal ki, Neogen dövründə Berinq boğazından keçən bir timsahdır. Müasir Amerika alliqatoru pleystosen paleontoloji salnamələrində yaxşı təmsil olunur[3].. Missisipi alliqatorunun tam mitoxondrial genomu 1990-cı illərdə sıralanırdı, o, timsahların məməlilərə və daha çox quşlara və onurğalılara aid bir dərəcədə inkişaf etdiyini söylədi[4]. Ancaq 2014-ci ildə nəşr olunan tam genom, alimlərin məməlilər və quşlara görə daha yavaş inkişaf etdiyini göstərir[5].

Missisipi alliqatorunun pəncələri xarakterik olaraq qısa, lakin kifayət qədər qüvvətli və yer üzündəki bədəni dəstəkləyə bilir[6]. Digər yer üzündə ölənlərin əksəriyyətindən fərqli olaraq, alliqatorlar əllərindəki proksimal bitmədən distal köməyi ilə sürətlərini artırırlar. Ön pəncə beş barmaq, on beş ayaqda yalnız dörd barmaq var. Suda timsahlar balıq kimi üzərək, çanaq sahəni və quyruq tərəfdən tərəfə hərəkət edirlər[7]. Alliqator qarın əzələləri bədənin içərisində ağciyərlərin mövqeyini dəyişə bilər və buna görə timsahın suya dalmağı, suyun qalxmasına və yuvarlanmasına imkan verən bükülmə mərkəzini köçürür[8].

Baş boynundan çox fərqlənir. Xüsusilə vəhşi alliqatorlar uzun və nazikdən qısa və kütləvi görünüşlərdə fərqlənir və bu, müəyyən şəxslərin genetik məlumatları, onların dietası və ətraf iqlim kimi faktorlar arasında fərqlər ola bilər. Alligatorların geniş sifətləri var,

Missisipi alliqatoru olduqca böyük bir heyvandır. Erkəklər ən azı 4.54 m, dişilər isə maksimum 3 m uzunluğa çatır. Ancaq 5 və ya 6.3 m uzunluğunda, yarım ton ağırlığında fərdlər də vardır. İstisna hallarda dişi timsah daha da böyük ola bilər[10][11]. XIX və XX əsrlərdə 5 metrdən çox uzunluqda olan alliqatorlar bilinmişdir, lakin bu məlumatlardan heç biri etibarlı sayılmır. Beləliklə, bildirilmiş ən böyük timsah, 1890-cı ildə Luizianada Marş Aylenddə vurulmuş bir erkək idi. Məlumatlara görə, uzunluğu 5,8 m-dir, ancaq nəqliyyat vasitəsi olmadığı üçün bu timsah ölçmə aparıldıqdan sonra palçıqlı sahildə qaldı[12]. Bu heyvanın ölçüləri düzgün göstərildiyi təqdirdə, çəkisi təqribən 1000 kq olmalıdır[13]. Floridada nə vaxtsa öldürülən ən böyük timsahın, qeyri-rəsmi məlumatlara görə, uzunluğu 5,31 m-dir[14][15]. Elmi dəlillərə əsasən, 1977-ci ildən 1993-cü ilə qədər Florida şəhərində öldürülən ən böyük timsah, yalnız 4.23 metr uzunluğunda və 473 kiloqram ağırlığında idi[16]. Ölçüsü ən böyük tanınmış alliqatora təxmin edilən başqa bir nümunə isə 4.54 m uzunluğunda ola bilər. Alabamada tutulan ən böyük timsahın uzunluğu 4,5 m və çəkisi 459 kq idi[17].Arkanzasda isə çox böyük bir timsah öldürüldü, bu da 4,04 metr uzunluğa çatdı və bildirildiyi kimi 626 kiloqram ağırlığında idi[18].

Lakin, Missisipi alliqatorları adətən belə böyük ölçülərə malik olmurlar. Erkəklərin əksəriyyəti yalnız 3,4 m-ə qədər böyüyür və 200 kq-dan çox kütləyə malik olurlarг[19], tam yetkin dişilərin normal ölçüsü isə 2,6 m, kütləsi 50 kq olur[20]. Floridanın Nyunans gölündə yetkin erkəklər yalnız 73.2 kq orta hesabla, yetkin dişilər isə 55.1 kq çəkir. Floridanın Qriffin Dövlət Parkında hər iki cinsin yetkinləri ortalama 57,9 kiloqram ağırlığında olur[21]. Cinsi yetkinliyə çatmış fərdlərin orta çəkisi təxminən 30 kiloqram, çəki göstəriciləri isə 160 kiloqramdır[22]. Missisipi alliqatorlarının erkəkləri dişilərindən fərqli olaraq daha çox olmasına baxmayaraq, bu növdə cinsi dimorfizm timsah dəstəsinin bəzi digər üzvlərindən daha az sayılır. Alliqatorların çəkisi, uzunluğu, yaşı, sağlamlığı, ilin vaxtı və mövcud qida qaynaqlarından asılı olaraq çox dəyişir. Böyük yetkin timsahlar yetkinlik yaşına çatmayanlarla müqayisədə nisbətən daha iri həcmli olurlar[23]. Digər sürünənlərə aid olan vəziyyətdə olduğu kimi, Amerika alliqatorları aralıq şimal hissələrində - Arkanzasın cənubundakı Alabama, şimal Karolina da adətən az olurlar.

Missisipi alliqatorları bir zamanlar 9452 nyuton gücünə qədər bir ölçü alətini sıxaraq, laboratoriyada dişləmə gücünə görə rekord keçirdilər. Qeyd etmək lazımdır ki, bu tədqiqatlar zamanı hələ də timsah əmrinin digər nümayəndələrinin dişləmə qüvvəsi ölçülməyib. Daha sonra müəyyənləşdirilmişdir ki, alliqatorların dişləmə qüvvəsi birbaşa heyvanın ölçüsündən asılıdır və yalnız bu istisna qısa müddətli yemək formalarıdır. Beləliklə, gələcəkdə daha böyük duzlu su timsahı və Nil timsahları alliqatorlardan daha çox ölçmə zamanı daha yüksək ədədlər verdi[24][25]. Çənələrin sıxma gücünün çox yüksək olmasına baxmayaraq, alliqatorların çənələrini açmaqdan məsul olan əzələlər zəifdir və heyvanları başlarına hərəkət etmədən müqavimət göstərmirsə, çənələri əlləri ilə və ya yapışan bant ilə bağlana bilər.

Missisipi alliqatorlarının təbii sahəsi Şimali Amerikadır — Atlantik sahilində və Meksika körfəzi boyunca ABŞ-ın cənub-şərq ştatları Şimali Karolina və Cənubi Karolina, Corciya, Florida, Texas və Luiziana daxildir. Şirin su hövzələrində yaşayırlar: çaylar, göllər, göllər və sulu sahələr, durğun su sahələrini üstün tuturlar. Yaşadığı ərazisi qurudursa, timsahlar başqa yerdən sığınacaq kimi istifadə edirlər. Şimal-mərkəzi Florida ştatında yaşayan timsahların həyat tərzi ilə bağlı bir araşdırmada erkəklərin bahar zamanı göllərin açıq sularını üstün tutduqları halda, dişilər həm bataqlıq, həm də açıq su obyektlərindən istifadə edirdilər. Yaz aylarında erkəklər də açıq suyu seçim edir, dişilər isə yuvalarını qurmaq və yumurta qoymaq üçün bataqlıqlara davam edir. Hər iki cinsin alliqatorları bəzən sığınacaq və ya qışlama sahələri üçün məkan qazanır və ya sadəcə ağac kökləri arasında yer tuturlar. Belə sığınacaqlar onlara çox isti və ya çox soyuq havaya dözməkdə kömək edir[26][27].

Alliqatorlar opportunist yırtıcılardır və tutulması mümkün olan hər şey ilə qidalana bilirlər. Əsasən həşərat, həşərat sürfələri, ilbizlər, hörümçəklər və qurdlar kimi onurğasızlarla qidalanır[28]. Onlar böyüdükcə, onlar mütənasib olaraq daha çox yırtıcı yeməyə qadirdirlər. Lakin, timsahın əksəriyyətindən fərqli olaraq, alliqatorlar nadir hallarda böyük heyvanlara hücum edir və böyük alliqatorlar tərəfindən tutulan qurbanların əksəriyyəti erkəklərdən daha kiçikdir[29]. Yetkinlərin pəhrizinin əsasları balıq, bağa, quş, ilan və kiçik məməlilərdən ibarətdir. Mədə məzmununun tədqiqi göstərir ki, ondatra və yenotlar məməlilər arasında ən çox yayılmış yemdir. Yemlərin əsasən yayıldığı Luizianada onlar bəlkə də yetkin erkək alliqatorlarının pəhrizinin əsas komponentidirlər. Köpəklər, pişiklər və buzovlar da daxil olmaqla ev heyvanları da zaman zaman timsahlar tərəfindən tutula bilər[30][31][32].

Vikianbarda Missisipi alliqatoru ilə əlaqəli mediafayllar var.

|year= (kömək) |title= (kömək) Missisipi alliqatoru (lat. Alligator mississippiensis) və ya Amerikan alliqatoru — iki tanınmış alliqator növündən biridir. Şimali Amerikada yaşayır və Cənub-Şərqi ABŞ üçün endemik sayılır.

Bu canlı Texas ştatından Şimali Karolinaya qədər göllər, çaylar və sipər bataqlıqları kimi suyun təzə sularında yaşayan böyük bir sürünən timsahkimiləri təmsil edir. Bu, simpatrik, kəskin timsahdan daha geniş bir ağız, qaranlıq rəng və duzlu su üçün daha az tolerantlıq ilə fərqlənir, soyuducu suya qovuşdurmaqla kompensasiya edilir. Cinsin ikinci nümayəndəsi olan Çin alliqatoru ilə müqayisədə, Missisipi alliqatoru daha böyükdür.

Alliqatorlar — balıqlar, amfibiyalar, sürünənlər, quşlar və kiçik məməlilər yeyən yırtıcılardır. Yeni doğulanlar xüsusilə onurğasızlara qidalanırlar. Quraqlıq mövsümündə digər orqanizmlərə ev sahibliyi edən xüsusi çuxurların qazılması, sulak ekosistemində mühüm rol oynayırlar. Bir il ərzində, xüsusilə yetişdirmə mövsümündə alliqatorlar ərazini qeyd etmək və uyğun tərəfdaşları tapmaq üçün səslər səsləndirirlər. Kişilər qadınları cəlb etmək üçün infrousadan istifadə edirlər. Yumurta su bədəninin yaxınlığında sığınacaq yerində düşmüş bitki örtüyündən, çubuqdan və kirdən hazırlanmış bir yuvaya qoyulur. Gənc timsahlar bədənin ətrafındakı sarı xətlər ilə anadan olurlar və bir ilə qədər ananın himayəsi altında olurlar.

Tarixən olaraq, bir zamanda tənzimlənməmiş ovlanma sayıları çox təsirləndi və Amerika timsahı bir zamanlar nəsli kəsilməkdə olan bir növ olaraq sıralandı. Lakin növlərin qorunması üçün sonrakı səyləri onların sayını dramatik şəkildə artırmağa imkan verdi və indi Missisipi timsahı əsasən onun yaşıllığı səbəbindən minimal risklə qorunub saxlanılır. Timsahlar dəriləri və ətləri üçün fermalarda istehsal olunur. Bu heyvan üç Amerika ştatının rəsmi dövlət sürünənləridir: Florida, Luiziana və Mississippi.

Aligator Amerika (Alligator mississippiensis) a zo ur stlejvil hag a vev e geunioù dour dous, lennoù ha stêrioù gevred Stadoù-Unanet Amerika.

Etre 2.5 ha 5.5 m eo o hirder, gris-gell pe du o liv ha ront o beg ledan.

Ar re vihan en em vag diwar divellkeineged, gleskered ha pesked pa'c'h a ar re vras da chaseal evned-dour ha bronneged.

Dre m'emañ lec'hiet uhel o daoulagad hag o divfronell war o fenn eo al lodennoù nemeto a zeu war-wel p'emañ ar peurrest eus o c'horf en dour. Evel-se e c'hellont chom koulz lâret diwelus o c'hedal o freizh.

Aligator Amerika (Alligator mississippiensis) a zo ur stlejvil hag a vev e geunioù dour dous, lennoù ha stêrioù gevred Stadoù-Unanet Amerika.

Aligátor severoamerický či aligátor americký, aligátor mississippský nebo aligátor štikohlavý (Alligator mississippiensis) je jeden ze dvou žijících druhů aligátorů, zástupce čeledi aligátorovitých (Alligatoridae). Aligátor severoamerický obývá pouze jihovýchod Spojených států amerických, kde žije v močálech, řekách nebo bažinách, které se často překrývají s oblastmi, které obývají lidé. Co do velikosti je větší, než jeho nejbližší příbuzný aligátor čínský (Alligator sinensis). Má velké, tmavé, silné tělo se silnými končetinami, širokou hlavou a velice silným ocasem. Samci těchto aligátorů dosahují většinou délky do 5,5 m, největší zaznamenaná délka dosahovala 5,8 m.[2] Ocas je téměř stejně dlouhý jako zbytek aligátorova těla a většinou funguje jako kormidlo při plavání. Občas ho můžou aligátoři použít jako zbraň, pokud se cítí ohrožení, a mířená rána tímto ocasem může představovat u menších živočichů i smrt, u člověka pak velice vážné zlomeniny. Aligátor severoamerický umí velice rychle a obratně plavat a občas i na zemi se může na krátkou vzdálenost pohybovat velice rychle.

Aligátoři požírají převážně ryby, ptáky, želvy, savce a obojživelníky. Důležitou část potravy tvoří u mladých aligátorů drobní bezobratlí, zvláště pak hmyz a jeho larvy, hlemýždi, pavouci nebo červi, občas si pochutnají i na drobných rybkách. Postupem času se začnou živit i většími rybami a dalšími vodními živočichy, žábami a pomalu i savci, zvláště pak krysami a dalšími myšovci. Téměř dospělí aligátoři loví živočichy v rozsahu od hadů a želv až k ptákům a středně velkým savcům.

Dospělí aligátoři severoameričtí se neostýchají zaútočit ani na kořist ve velikosti prasat, jelenů a domácích zvířat, zvláště pak koz a ovcí, která se chodívají napít k napajedlu. Časté jsou i případy kdy zaútočí na menšího a slabšího zástupce svého druhu. Větší samci si troufnou i na velké šelmy, jako pumy nebo dokonce medvědy, což činí z aligátora severoamerického jednoho z nejnebezpečnějších severoamerických lovců z říše živočichů.

V žaludcích aligátorů severoamerických jsou často nalézány i drobné kameny, které aligátoři požírají pro semletí potravy, což umožňuje jednodušší trávení. Tento proces je velice důležitý, jelikož aligátor požírá svou kořist až na větší zvířata v celku.

I přesto, že sdílí některé lokality s lidmi, jsou útoky na člověka spíše ojedinělou záležitostí. Naopak, aligátoři se lidí spíše bojí a většinou se jim snaží obloukem vyhýbat a většina útoků na lidi je způsobena tím, že lidé aligátory krmí. Kousnutí aligátora je velice nebezpečné a pokud k němu dojde, neměl by člověk váhat a naopak by měl vyhledat nejbližšího lékaře. Pokud tak neučiní, může dojít k velice nebezpečné infekci a následně k amputaci postiženého místa, v tomto případně nejčastěji nohy.

Výzkum ukázal, že aligátoři často záměrně polykají kameny, aby se dokázali lépe a déle udržet pod vodou při potápění do větších hloubek.[3][4]

Aligátoři severoameričtí se páří v mělkých vodách obvykle v dubnu. Před pářením se konají pomalé námluvy při kterých, ačkoli nemají aligátoři hlasivky, vydávají samci výrazné zvuky, kterými přitahují pozornost samic. Samec se několik dní zdržuje se samicí a občas ji „pohladí“ přední nohou a čeká na samiččino rozhodnutí, zda dá souhlas k spáření či ne.

Samice si poblíž vody vybere místo na postavení hnízda, na které začne ocasem i končetinami shrabovat všechnu možnou dostupnou rostlinnou vegetaci. Nakonec vypadá hnízdo jako hromada rostlin s prohlubní uprostřed, kam samice klade 28 až 52 bílých vajec, velikostí podobných husím a prohlubeň zahrabe dalším rostlinstvem. Samice po dobu zhruba 65 dní vejce chrání. Po vylíhnutí začnou mláďata vydávat pronikavý skřehotavý zvuk, což je znamení pro samici, že je musí co nejrychleji z hnízda vyhrabat. Mláďata jsou podobná svým rodičům, jen mají několik žlutých skvrn na těle. U matky se zdržují maximálně po dobu tří let a pohlavní dospělosti dosahují zhruba v 8 až 13 letech.

Aligátora chová např. ZOO Ústí nad Labem, Krokodýlí ZOO Protivín,ZOO Zlín V minulosti byl v tuzemských zoo častější, nikdy se v nich nerozmnožil.

V tomto článku byl použit překlad textu z článku American Alligator na anglické Wikipedii.

Aligátor severoamerický či aligátor americký, aligátor mississippský nebo aligátor štikohlavý (Alligator mississippiensis) je jeden ze dvou žijících druhů aligátorů, zástupce čeledi aligátorovitých (Alligatoridae). Aligátor severoamerický obývá pouze jihovýchod Spojených států amerických, kde žije v močálech, řekách nebo bažinách, které se často překrývají s oblastmi, které obývají lidé. Co do velikosti je větší, než jeho nejbližší příbuzný aligátor čínský (Alligator sinensis). Má velké, tmavé, silné tělo se silnými končetinami, širokou hlavou a velice silným ocasem. Samci těchto aligátorů dosahují většinou délky do 5,5 m, největší zaznamenaná délka dosahovala 5,8 m. Ocas je téměř stejně dlouhý jako zbytek aligátorova těla a většinou funguje jako kormidlo při plavání. Občas ho můžou aligátoři použít jako zbraň, pokud se cítí ohrožení, a mířená rána tímto ocasem může představovat u menších živočichů i smrt, u člověka pak velice vážné zlomeniny. Aligátor severoamerický umí velice rychle a obratně plavat a občas i na zemi se může na krátkou vzdálenost pohybovat velice rychle.

Amerikansk alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) er den ene af de to nulevende arter i slægten Alligator.

Den franske zoolog François Marie Daudin gav arten det videnskabelige navn Alligator mississipiensis i 1802 idet han troede, at Mississippi-floden blev stavet med kun et 'P'. Den Internationale Kommission for Zoologisk Nomenklatur (ICZN) henstiller til, at man skriver artsnavnet med dobbelt-p, da navnet refererer til Mississippi-floden.

Voksne hunner af den amerikanske alligator bliver normalt op til 2,6 meter lange, mens voksne hanner bliver omkring 3,4 meter.[2] Den største han nedlagt i 1890 menes at have målt 5,8 meter.[3] Det største videnskabeligt bekræftede eksemplar er en han fra Florida, der målte 4,23 m og vejede 473 kg.[4] Ca. halvdelen af kropslængden udgøres af halen, så selve dyret opfattes ofte som kortere end det er. Alligatorer vokser hele livet, men efter at de er blevet kønsmodne, sker væksten i et meget langsomt tempo.

Alligatorhanner har en markant forhøjning yderst på snuden, mens denne forhøjning er mindre markant eller slet ikke eksisterende hos hunnerne.

De unge dyr har på kroppens sider gule striber på en sort baggrund, der virker som camouflage. Efterhånden som dyret bliver ældre, bliver disse striber olivenfarvede, brune og til sidst sorte. Ellers er de voksne alligatorers farve på ryg og sider mørkt olivengrøn, men farven kan variere og er ofte næsten helt sort. På bugen er alligatorer lysere, nærmest flødefarvede. Den mørke farve på ryggen gør den sværere at opdage for byttedyr over vandet, der ofte ser nærmest sort ud, mens den lyse farve på bugen, gør dem sværere at se for byttedyr, der befinder sig under dem, da de så ser dem op mod overfladen.

Alligatorer er forholdsvis hurtige og adrætte dyr i modsætning til, hvad man skulle tro. I vandoverfladen kan alligatorer svømme op til 16 km i timen, og neddykkede kan deres hastighed komme op i nærheden af 25 km i timen. Også på land er alligatoren hurtig, 15–20 km i timen, og over meget korte distancer kan de nå op på næsten 50 km i timen. Alligatorer kan også springe ud af vandet. Unge alligatorer kan springe helt ud af vandet, mens ældre og tungere alligatorer typisk kan springe ca. 2/3 af deres egen kropslængde. Man skal derfor være forsigtig, når man jager eller på anden måde beskæftiger sig med alligatorer.

En af grundene til, at de kan være så hurtige, skyldes nok at alligatorer ånder ligesom fugle. [5]

Alligatorens øjne er placeret, så den ikke kan se fremad men kun til siden, mens krokodillers øjne er placeret, så de ser fremad. Hvis man lyser på en alligators øjne i mørke, skinner de rødt.

Alligatoren lever i subtropiske ferskvandsområder, så som marskområder, sumpe, floder, søer mm.

Den amerikanske alligator lever i det sydlige USA (se kortet i boksen), i staterne Alabama, Arkansas, North Carolina og South Carolina, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma og Texas. I begyndelsen af de 20. århundrede fandt der en voldsom jagt sted på alligatorer, som primært blev jaget på grund af deres skind. I 1967 blev den amerikanske alligator registreret som en truet dyreart, og op gennem 1970'erne begyndte man et succesfuldt genopretningsprojekt for bestanden, blandt andet med totalt jagtforbud og udsætning af voksne eksemplarer, og i dag er antallet af amerikanske alligatorer omkring et par millioner. Heraf findes ca. 1 million i Florida og ca. 750.000 i Louisiana. Arten er slettet på listen over truede dyrearter, men er stadig på observationslisten over arter i risikogruppe. En af grundene til at arten fortsat holdes på observationslisterne, er at de har en stor lighed med den amerikanske krokodille, der fortsat er truet af udryddelse. Florida er det eneste sted i verden, hvor der både findes krokodiller og alligatorer i naturen, og der er kun mellem 500 og 1000 eksemplarer af den amerikanske krokodille tilbage i staten.

Alligatorer er territoriale dyr, og voksne hanner hævder et territorium på omkring 1,5 km af vandområdet, de lever ved, mens hunner hævder territorier på ca. det halve. Yngre og mindre alligatorer hævder mindre eller ingen territorier.

Alligatorer har en ingen stemmebånd, men hannerne kan udstøde nogle "brøl" som i parringssæsonen bruges til at lokke hunnerne til. Hør et alligatorbrøl her:

En han parrer sig med 10-15 hunner på en parringssæson, der ligger i forårsmånederne. Hunnerne bliver kønsmodne, når de er omkring 7 til 10 år gamle, derefter parrer de sig hvert år, så længe de lever. I naturen kan alligatorer blive omkring 50-70 år gamle, i fangenskab helt op til 90 år. Hunnerne lægger mellem 20 og 50 æg ad gangen. Imidlertid er det kun omkring 2-3% af ungerne, der overlever til voksenalderen. En alligatorunge er ca. 15 cm lang, når den udklækkes og i naturen vokser de ca. 30 cm pr år. Når en alligator er omkring 1 meter lang, har den ingen naturlige fjender, bortset fra mennesket, mens unge alligatorer er føde for såvel fugle, som store fisk og andre alligatorer.

Alligatorers køn er ikke bestemt lige fra befrugtningstidspunktet, som, tilfældet er hos fx pattedyr. Hvilket køn ungerne får afhænger af den temperatur æggene udsættes for under udrugningen, der varer ca. 65 dage. Hvis temperaturen er under 30 grader celsius, bliver alle æg til hunner, er temperaturen over 34 grader bliver alle æg til hanner. Temperaturer mellem 30 og 34 grader giver unger af begge køn. Æggene lægges i reder, som hunnerne bygger af græs og blade, og rederne placeres ofte på bredden af bayous eller på ”flydende øer”, der driver rundt i marsken. Formålet med rederne er primært at hæve æggene op fra vandoverfladen, så risikoen for at de oversvømmes bliver mindre. Når æggene er lagt dækkes reden af mere vegetation og mudder. Plantedelene rådner efterhånden, hvilket skaber varme, som er med til at udruge ungerne.

Hunnen bliver ikke altid ved reden, når æggene er lagt, men hun holder sig i nærheden, og trues reden vil hun lynhurtigt vende tilbage for at forsvare den. Når æggene er klar til at klækkes, vil hunnen ”åbne” reden, og hjælpe ungerne med at komme ud af ægget, ved at knuse dette forsigtigt mellem tænderne. Kommer moderen ikke tilbage til reden, vil ungerne med stor sandsynlighed dø, for mange kan ikke komme ud af ægget ved egen hjælp, og de vil sandsynligvis ikke kunne komme gennem det lag af vegetation og tørret mudder, der dækker reden. Når æggene er klækket, vil hunnen tage mellem 8 og 10 unger i munden ad gangen og bære dem ned til vandet. Her ryster hun på hovedet i vandet, og får på denne måde ungerne til at svømme ud af munden. Når de kommer ud i vandet, vil ungerne danne stimer, evt. sammen med unger fra andre reder, og de bliver sammen med deres mor i en lang periode, normalt mindst et år, men af og til op til både to og tre år. I den tid passer hunnen på ungerne. Alligatoren er det eneste krybdyr, der passer på sin yngel på denne måde.

Om vinteren og i tørkeperioder går alligatorerne i hi i huler, som de graver i brinkerne på de vandområder, hvor de holder til. "Alligatorhulerne" kan ligge så langt som 6 meter inde i brinkerne, og hulerne graves, så der er luft nok til at alligatorerne kan trække vejret. I disse huler kan dyrene overleve, selv om temperaturen uden for falder til under frysepunktet. På særligt varme dage kommer de ud af deres hi, og lægger sig i solen og varmer sig. Skulle det blive frost mens en alligator er ude af hiet, kan den også overleve korte perioder med frost i modsætning til krokodiller, som vil fryse ihjel i frostvejr, og som derfor ikke kommer ud af hiet i hele dvaleperioden. I dvaleperioden indtager alligatorerne ingen føde, men tærer på de energidepoter, de har opbygget, især i halen, i løbet af sommeren. Også i vand, kan alligatorer overleve i frostvejr. De lægger sig i overfladen med næseborene over vandet, så hvis overfladen fryser, kan de stadig trække vejret. Man har i øvrigt eksempler på, at alligatorer, der er frosset helt fast i is og hvor også næseborene er blevet dækket, har kunnet overleve i op til 8 timer uden at trække vejret!

Alligatorer lever af megen forskellig føde. Unge alligatorer lever primært af små, hvirvelløse dyr, frøer og små fisk. Efterhånden som de vokser udvides føden til at omfatte større fisk, små pattedyr, skildpadder, vandfugle og krybdyr, herunder også mindre alligatorer. Desuden æder alligatorer gerne ådsler af større dyr. Der er rapporteret om hændelser, hvor alligatorer har ædt hunde og andre husdyr, der har svømmet i floder eller bayous, og alligatorer har også angrebet mennesker. Her mener man dog, at alligatorerne må have forvekslet mennesket med et mindre byttedyr eller have følt sig truet. I modsætning til krokodiller betragter alligatorer ikke mennesker som naturlige byttedyr.

Når en alligator skal åbne munden, er den ikke særligt god til det; man kan faktisk med to fingre holde en alligatorens kæber sammen. Når den skal lukke den igen, gør den det så meget mere effektivt. En fuldvoksen gennemsnitsalligator kan bide sammen med mere end 800 kg pr. kvadratcentimeter, hvilket betyder at den nemt kan knuse skjoldet på selv ret store skildpadder foruden knogler på andre dyr, som de æder.

Alligatorerne ligger og lurer i vandoverfladen, med kun øjnene og næseborene over vandet, og når de opdater et byttedyr angriber de det, og sluger det helt. En alligator har ca. 80 tænder i munden ad gangen og når tænderne er slidt, skiftes de. En gennemsnits alligator kan få mellem 2- og 3.000 tænder i løbet af sine levetid, men tænderne kan ikke anvendes til at tygge med, kun til at fastholde, rive og flå. Er byttedyret for stort til at sluge helt, (fx et dådyr eller lignende) trækker alligatoren det ned under vandet og drukner det, ved den såkaldte dødsrulning, hvor alligatoren simpelthen roterer om sin egen længdeakse indtil dyret er druknet eller mindre stykker løsrives fra dyret.. Når dyret er druknet, gemmer alligatoren det under en sunket træstamme, eller andet, der er egnet til at fastholde byttet. Her får det så lov til at ligge og gå i forrådnelse i 2-3 uger, indtil alligatoren kan rive stykker af det, og sluge disse.

Når en alligator har føde, spiser den alt det den overhovedet kan komme af sted med. Er der føde nok, kan den næsten bogstaveligt spise til den revner. Der er eksempler på, at alligatorer har ædt sig ihjel, når der var føde nok. Til gengæld kan de overleve uden føde i lange perioder, hvis der er fødeknaphed i deres territorium. Hvor meget føde, de har behov for afhænger også af omgivelsernes temperatur. Jo koldere det er, jo mindre behøver alligatoren at spise. Når vandtemperaturen falder til omkring 27 grader celsius begynder de at miste appetitten, og omkring 20 grader holder de simpelthen op med at fouragere.

I Florida, Texas og Louisiana er alligatorfarme almindelige. I 1970'erne blev mange af disse farme oprettet som en del af genropretningsprojekt for alligatorbestanden og dette projekt løber fortsat. Derfor indsamles æg fra alligatorreder, og disse udklækkes så på farmene, hvor dyrene så bliver til de er omkring 2-3 år gamle. På farmene er væksten op mod det dobbelte af væksten i naturen, så når ungerne udsættes i naturen er de 1 – 1,5 meter lange og har dermed betydeligt større chance for at overleve. Det har vist sig, at omkring 15-20% af de indsamlede æg udvikler sig til alligatorer, som efter udsættelse overlever ind i voksenalderen i modsætning til de 2-3% af de æg, der udklækkes i naturen.

I dag drives også alligatorfarme med henblik på en kommerciel udnyttelse af alligatorerne. Hoveder eller kranier sælges ofte som souvenirs til turister. Skindet forarbejdes til beklædning, sko, bælter eller tasker og punge. Kødet sælges også og anvendes som føde. Blandet andet sælges mørbrad og filet og af og til kan man også købe "alligator vinger", der er fødderne. Kødet er meget magert, kun 2 gram fedt pr. 100 g og slet ingen kulhydrater. Kødet fra halen er hvidt og meget mørt, mens det fra resten er dyret er mørkere og noget fastere. Konsistensen af kødet er som kylling og smagen er let fiskeagtig. Der laves også alligatorpølser, som for pølseelskere skulle være en stor delikatesse. De består typisk af 75% alligatorkød og 25% svinekød. I alt sælges i USA omkring 135 tons alligatorkød til føde hvert år.

I Louisiana findes der ca. 750.000 alligatorer, og for at holde bestanden på et rimeligt niveau og dermed sikre at hele økosystemet ikke generes af en overproduktion af alligatorer, gives der årligt tilladelse til at nedlægge omkring 30.000 dyr. Hvert år laver biologer et overslag over den samlede bestand, og hvor stor en procentdel denne skal reduceres med. Det kan fx være 3-4%.

Det er imidlertid ikke alle, der må jage alligatorer. Ejer man et område med alligatorer bliver bestanden i det konkrete område vurderet af biologer og vildtkonsulenter. Skønner de, at der er fx 100 alligatorer i området, og der skal jages 4% på statsplan, får ejeren tilladelse til at fange 4 alligatorer. Denne tilladelse kan ikke overdrages. Det er dog muligt at lade andre stå for jagten, hvis bare ejeren af det pågældende område deltager i jagten. Det benytter nogle ejere sig af, til at sælge alligatorjagtture for flere tusinde dollars.

For hver alligator, der gives tilladelse til at fange, udleveres et særligt mærke til ejeren, som identificerer denne. Straks når alligatoren er fanget, skal dette mærke sættes i dyrets skin, nærmere betegnet i det 6 rygskæl, talt fra halespidsen, og mærket ”forsegles”. Dette mærke skal blive i skindet under hele forarbejdningsprocessen, indtil skindet bruges til jakker, bælter eller tasker. Mærket kontrolleres jævnligt undervejs af myndighederne, og de virksomheder, der forarbejder skindet, skal kunne gøre rede for alle de skind, de har brugt. Kun skind, der er forsynet med mærke, må indhandles. Da der kun udleveres et antal mærker, svarende til det antal dyr, der må nedlægges, kan man på denne måde kontrollere jagtens størrelse. "Krybskytteri" på alligatorer straffes strengt, og det gælder både for jægere, der nedlægger flere dyr end de har tilladelse til, og for jægere, der nedlægger dyr helt uden tilladelse eller uden for deres eget område. I Louisiana straffes krybskytteri på alligatorer med 10 års fængsel og $10.000 i bøde som maksimum, og maksimumstraffen anvendes stort set altid. Er krybskytten en autoriseret alligatorjæger, får han desuden altid inddraget sin licens. Selve fangsten af alligatorer er under alle omstændigheder begrænset til eksemplarer på minimum 6 fod (183 cm). Mindre eksemplarer skal sættes ud igen. Jagten er desuden begrænset til få måneder hvert år.

Fangsten foregår typisk på den måde, at alligatorjægeren om aftenen sejler ud til de steder, hvor han ved at alligatorer holder til. Her binder han en ca. 10 meter lang snor til en gren, et godt stykke over vandoverfladen. I enden af snoren sidder en ca. 10 cm lang og ca. ½ cm tyk jernkrog. På denne krog anbringes en kylling, der har været slagtet i 5-6 dage, så den har en kraftig lugt af ådsel. Krogen anbringes, så den hænger 50–60 cm over vandet. Derefter forlader jægeren stedet. Alligatorer, der primært jager om natten, får nu færten af byttet. De ”springer” ud af vandet og sluger kyllingen hel, og dermed også krogen. Når de nu svømmer væk, vil de trække snoren ud til de ikke kan komme længere. Når de opdager at de ”er fanget”, vil de dykke ned til bunden og gemme sig i mudderet. Krogens placering inde i kyllingen sikrer at alligatoren ikke såres af krogen. Næste dag kommer ejeren så tilbage og kontrollerer fælden. Når han kan se, at krogen ikke længere hænger på sin plads ved han, at der er en alligator i den anden ende. Nu vil han så – meget forsigtigt – hale alligatoren op fra bunden. Hvis alligatoren er under 6 fod kappes snoren, og alligatoren kan svømme væk. Krogen lader man forblive hvor den er. Alligatoren har så stærk en mavesyre, at selv en så kraftig krog som man anvender til fangsten, vil være gået fuldstændigt i opløsning på 3-4 uger – uden at alligatoren er blevet skadet. Er alligatoren stor nok, skal den derimod slås ihjel. Tidligere knuste man hovedet på den med en økse, men den metode er man gået bort fra i dag. Efter at man begyndte at sælge kranierne til turister, var det simpelt hen for besværligt at rekonstruere dem, når kraniet var knust. Nogle jægere stikker en kniv i hjernen på dyret, men den mest almindelige metode er at skyde den med en kaliber 22 riffel. Her gælder det dog om at ramme meget præcist. Alligatorens hud på hovedet er meget hård, og hovedskallen er meget kraftig, så der er kun et lille område lige over øjnene, hvor man kan skyde dyret. Hvert år er der jægere, som ikke rammer rigtigt, og så sker det at de selv eller deres jagtkammerater bliver ramt at kuglen, der rikochetterer fra dyrets hoved – af og til med dødelig udgang, og så kan man vel sige, at det var alligatoren, som trak det længste strå.

Bortset fra jagtulykker, hvor der altså dør 2-3 mennesker om året, har der i mange år kun været få konfrontationer mellem alligatorer og mennesker, da alligatorer som regel holder sig på afstand af mennesker i modsætning til mange krokodillearter, fx nilkrokodillen, der opfatter mennesker som naturlige byttedyr. Det sker dog at alligatorer dræber mennesker. Fra 1970 til slutningen af 1990'erne blev 9 mennesker dræbt af alligatorer i USA. Ofte sker dødsfald som følge af infektioner forårsaget af alligatorbid, eller som følge af at et menneske bliver ramt af et slag fra alligatorens hale.

Antallet af rapporter om alligatoroverfald på mennesker er dog vokset meget inden for de seneste 5 år, hvor 11 mennesker i USA er blevet dræbt af alligatorer, alene 3 i 2006. Årsagen til denne stigning er formodentlig at mennesket trænger mere og mere ind på alligatorernes leveområder, og at man ikke respekterer at alligatoren faktisk er et rovdyr. Ikke mindst er alligatorhunner meget aggressive overfor alt, hvad der nærmer sig rederne, når der er æg.

Som med mange andre rovdyr, fortælles der mange historier om alligatorer. Her er et par stykker:

Amerikansk alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) er den ene af de to nulevende arter i slægten Alligator.

Der Mississippi-Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), auch Hechtalligator genannt, ist ein im Südosten der USA lebender Alligator.

Der Mississippi-Alligator kommt in den Bundesstaaten North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma und Texas vor, wo er meist langsam fließende Süßwasserflüsse, Sümpfe, Marschland und Seen bewohnt. Jedoch gab es auch schon Sichtungen in Memphis, Tennessee.

In Florida kommt der Mississippi-Alligator unter anderem im Everglades-Nationalpark vor.

Der Mississippi-Alligator wird bis zu sechs Meter lang, weist jedoch meist nur eine Länge von dreieinhalb bis vier Metern auf. Die Schnauze der Tiere ist breit, flach und vorn stumpf abgerundet. Die Färbung ist dunkel, fast schwarz, die Jungtiere haben gelbliche Querbänder. Die Bauchseite ist dunkel, kann aber auch hell sein.

Das Nahrungsspektrum der Alligatoren ist sehr groß und umfasst Fische, Vögel, Schildkröten, Schnecken und Säugetiere. Jungtiere, für die größere Beute noch ungeeignet ist, vertilgen Insekten, Spinnen, Larven, Weichtiere und Würmer. Ausgewachsene Exemplare erbeuten sogar Tiere von der Größe eines Schafes oder Wildschweins. Auch kleinere Artgenossen sind nicht vor ihnen sicher. Angriffe auf Menschen sind jedoch eher selten, da Alligatoren Menschen scheuen.

Die Paarungszeit des Mississippi-Alligators beginnt im Frühjahr. Die Männchen erzeugen in dieser Zeit tiefe Bellgeräusche, um die Weibchen anzulocken und ihre Konkurrenten auf Distanz zu halten. Sie verfügen jedoch über keine Stimmbänder, sondern erzeugen die Geräusche mit ihrer Lunge. Das Weibchen errichtet in Wassernähe ein Nest aus pflanzlichem Material. Dort legt es bis zu 50 Eier ab, welche durch die Wärme der verrottenden Pflanzen ausgebrütet werden. Dabei hängt es von der Bruttemperatur ab, welches Geschlecht die Jungtiere haben werden. Das Weibchen beschützt sein Gelege bis zum Schlupf der Jungtiere, welche es ausgräbt und in seinem Maul zum Wasser trägt. Die gelbgestreiften Jungtiere ernähren sich zunächst noch von ihrem Dottersack und bleiben etwa fünf Monate in der Nähe ihrer Mutter, ehe sie ein eigenständiges Leben beginnen. Diese beschützt sie auch vor ihren zahlreichen Feinden wie Waschbären, Reihern und den eigenen Artgenossen.

Es gibt nicht viele Hinweise auf den Umgang der Ureinwohner mit den Alligatoren. Lediglich eine Radierung von Theodore de Bryce Le Moin aus dem Jahr 1565 zeigt Indianer aus dem heutigen Florida, die Alligatoren mit langen Spießen jagen. Erst in den letzten Jahrhunderten wurden die Krokodile ihrer Häute und ihres Fleisches wegen intensiv bejagt. Die ersten Erwähnungen zur Nutzung von Krokodilhäuten stammen aus dem Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts. Eine kommerzielle Jagd setzte mit dem Sezessionskrieg 1861 bis 1865 ein. Die Nachfrage nach Produkten aus Krokodilleder, besonders nach Schuhen, Gürteln und Taschen stieg in dieser Zeit deutlich an. Auch der Fang von Jungalligatoren und deren Verkauf – lebend oder präpariert – war sehr lukrativ. Um etwa 1900 brachen die Bestände des Mississippi-Alligators aufgrund der starken Bejagung zusammen, und die Krokodiljagd verlagerte sich nach Mittel- und Südamerika. Laut IUCN gilt die Art mittlerweile wieder als ungefährdet. Nach dem BNatSchG ist der Mississippi-Alligator allerdings seit dem 31. August 1980 besonders geschützt.[1] Die Einfuhr lebender oder toter Tiere in die Europäische Union bedarf der Genehmigung ebenso wie die Einfuhr von Waren, die aus Teilen des Mississippi-Alligators hergestellt wurden.

Die Haltung von Alligatoren als Terrarientiere ist aufgrund der Größe und Unberechenbarkeit der Tiere vergleichsweise schwierig. In Tiergärten sind Mississippi-Alligatoren jedoch recht häufig zu finden.

Für Menschen können Alligatoren zur Gefahr werden, wenn sie sich an Flüssen aufhalten oder mit kleinen Motorbooten auf dem Fluss bewegen, da der Motorenlärm die Angriffslust verstärken kann. CrocBITE, die weltweite Datenbank für Krokodilangriffe der Charles Darwin University, registrierte seit 1969 (Stand: Juli 2019) 243 Attacken durch Mississippi-Alligatoren auf Menschen, 37 davon endeten für das Opfer tödlich.[2]

Alligatoren und Kaimane vertragen Kälte viel besser als echte Krokodile. So kann der Mississippi-Alligator in einer Kältestarre über zwei bis drei Monate selbst Minusgrade überleben[3], ohne sich einzugraben. Dabei liegt er im Flachwasserbereich, sodass nur seine Schnauzenspitze aus der Wasseroberfläche herausragt. Gefriert das Gewässer, bleibt durch dieses selbstgeschaffene Atemloch eine Möglichkeit zu atmen.[4]

Mississippi-Alligatoren verfügen, wie andere Vertreter der Crocodylia auch, über ein ausgeprägtes Kommunikationssystem, da ihnen eine Vielzahl verschiedener Laute zur Verfügung stehen. Der Paarungsruf („bellow“) des Mississippi-Alligators kann eine Lautstärke von 91–94 Dezibel an Land und 121–125 Dezibel unter Wasser erreichen,[5] wobei die Formanten des Rufes Hinweise auf die Größe des Tieres liefern.[6]

Für den Mississippi-Alligator wurden 1984 Hinweise auf einen Magnetsinn publiziert.[7]

Der Mississippi-Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), auch Hechtalligator genannt, ist ein im Südosten der USA lebender Alligator.

The American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), whiles referred tae colloquially as a gator or common alligator, is a lairge crocodilian reptile endemic tae the sootheastren Unitit States. It is ane o twa livin species in the genus Alligator within the faimily Alligatoridae; it is lairger nor the ither extant alligator species, the Cheenese alligator. Adult male American alligators meisur 3.4 tae 4.6 m (11 tae 15 ft) in lenth, an can weigh up tae 453 kg (1,000 lb). Females are smawer, meisurin around 3 m (9.8 ft). The American alligator indwalls freshwatter wetlands, such as marshes an cypress swamps frae Texas tae North Carolina. It is distinguished frae the sympatric American crocodile bi its broader snout, wi owerlappin jaws an darker colouration, an is less tolerant o sautwatter but mair tolerant o cuiler climates nor the American crocodile, which is foond anly in tropical climates.

The American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), whiles referred tae colloquially as a gator or common alligator, is a lairge crocodilian reptile endemic tae the sootheastren Unitit States. It is ane o twa livin species in the genus Alligator within the faimily Alligatoridae; it is lairger nor the ither extant alligator species, the Cheenese alligator. Adult male American alligators meisur 3.4 tae 4.6 m (11 tae 15 ft) in lenth, an can weigh up tae 453 kg (1,000 lb). Females are smawer, meisurin around 3 m (9.8 ft). The American alligator indwalls freshwatter wetlands, such as marshes an cypress swamps frae Texas tae North Carolina. It is distinguished frae the sympatric American crocodile bi its broader snout, wi owerlappin jaws an darker colouration, an is less tolerant o sautwatter but mair tolerant o cuiler climates nor the American crocodile, which is foond anly in tropical climates.

Amerikańsczi aligator (Alligator mississippiensis) – to je ôrt gadzënë z rodzëznë aligatorowatëch. Òn żëje w Nordowi Americe.

Bí-kok té-chhùi-kho̍k (Eng-gí: American alligator), ha̍k-miâ Alligator mississippiensis, sī té-chhùi-kho̍k (alligator) ê nn̄g chéng chi it. Chit chióng kho̍k-hî tī Bí-kok ê tang-lâm tē-khu ê tâm-tē seng-oa̍h.

Bí-kok té-chhùi-kho̍k (Eng-gí: American alligator), ha̍k-miâ Alligator mississippiensis, sī té-chhùi-kho̍k (alligator) ê nn̄g chéng chi it. Chit chióng kho̍k-hî tī Bí-kok ê tang-lâm tē-khu ê tâm-tē seng-oa̍h.

Американскиот алигатор (Alligator mississippiensis) е еден од двата преживеани видови на алигатори, род од фамилијата Alligatoridae. Американскиот алигатор живее само на територијата на југоисточен САД, каде ги населува мочурливите земјишта. Овој вид е поголем од другиот преживен вид на алигатор – кинескиот алигатор.

Американскиот алигатор го среќаваме во југоисточниот дел на САД, од Северна Каролина, јужно до Флорида и западно до јужниот дел на Тексас. Ги среќаваме во државите Северна Каролина, Јужна Каролина, Џорџија, Флорида, Алабама, Мисисипи, Арканзас, Луизијана, Тексас и Оклахома.

Иако првенствено се слатководни животни, алигаторите понекогаш ги среќаваме и во деловите каде има мешање на слатка и морска вода[1]. Овие животни живеат во мочуришни земјишта. Алигаторите зависат од мочуриштата, и на одреден начин и мочуриштата зависат од нив. Како суперпредатори, тие ја контролираат бројноста на популациите на глодари и други животни кои доколку се во преголем број можат да ја уништат мочуришната вегетација.

Американските алигатори се поотпорни на ладно од американскиот крокодил. За разлика од крокодилите кои на температура од -13 оС брзо подлегнуваат на ладното и се дават, американскиот алигатор ги издржува овие температури без проблеми[2]. Се смета дека поради оваа адаптативна карактеристика алигаторите се далеку пораспространети на север од американските крокодили[2]. Всушност американскиот алигатор е најсеверно распространето крокодиловидно животно, и најотпорен на ниски температури[3].

Најголема корист за мочуриштето и неговите жители се „алигаторските дупки“ кои ги градат возрасните индивидуи на алигатори и ги прошируваат низ годините[4]. Алигаторот ја употребува устата и канџите да ја раскопува вегетацијата за да го расчисти просторот, а потоа туркајќи со телото и удирајќи со опашката, создава депресија која се полни со вода за време на влажната сезона а потоа ја држи водата откако ќе престанат дождовите. За време на сувата сезона, поточно за време на големите суши, алигаторските дупки ги снабдуваат со вода рибите, инсектите, раковите, змииите, желките, птиците и другите животни вклучувајќи го и алигаторот.

Понекогаш, алигаторот може да ги прошири овие дупки со копање под надвиснат брег за да создаде скриено дувло. После тунелот кој може да биде долг и до 6 метри, тој го проширува дувлото, прваејќи еден вид на соба со таван доволно повисок од нивото на водата за да има простор за дишење. Ова не е алигаторско гнездо, туку само начин за преживување на сувата сезона и зимата.

Американскиот алигатор има широко, малку заоблено тело со широка глава и многу моќна опашка. Најчесто имаат темнозелена, кафена, сива или скоро црна боја на кожата со кремави нијанси на стомакот. Водите богати со алги им даваат на алигаторите позеленкаста боја, додека танините од надвиснатите дрвја им даваат потемна боја. Возрасните мажјаци се долги помеѓу 3,96 и 4,48 метри, додека женките се со просечна должина од 3 метри[5][6]. Најтешките мажјаци од овој вид достигнуваат околу 473 килограми, а најтешките жeнки околу 130 килограми[7]. Најголемиот регистриран американски алигатор бил со должина од 5,8 метри[8]. Опашката која е половина од вкупната должина на алигаторот првично се користи за пливање. Опашката исто така ја користат и како оружје за одбрана доколку се почувствуваат загрозени. Алигаторите во вода се движат многу брзо, но затоа се далеку побавни на копно. Поседуваат пет канџи на двете предни нозе и по четири канџи на задните. Американскиот алигатор има најсилен загризок од сите живи животни. Измерен во лабораториски услови изнесува 9452 N[9].

Некои алигатори не го поседуваат генот за меланин, што ги прави албино. Овие алигатори се екстремно ретки и е речиси невозможно да се сретнат во дивината. Албино алигаторите преживуваат само во заробеништво. Како сите албино животни, и овие се многу ранливи на сонце и лесно забележливи за предаторите[10].

Алигаторите се хранат со риби, птици, желки, змии, цицачи и влекачи. Младенчињата сепак се хранат со помал плен како без’рбетници, односно инсекти, ларви, полжави, пајаци и црви. Тие исто така јадат и мали риби. Како растат така одбираат се поголем плен. Така за кратко време тие почнуваат да јадат риби, мекотели, жаби и мали цицачи како стаорци и глувци. Младите алигатори имаат поголем избор на плен, од змии и желки до птици и цицачи со средна големина како ракуни.

Откако ќе достигнат зрелост секое животно кое живее во водата или доаѓа до водата за да пие вода е потенцијален плен. Возрасните крокодили јадат и елени, домашни животни од типот на крава и овца, но и помали алигатори. Во ретки случаи забележани се големи мажјаци на американски алигатор како ловат американска црна мечка или пантер од Флорида, што го прави алигаторот вистински суперпредатор во регионите каде што живее[11]. Американскиот алигатор е познат и под името „Кралот од Еверглејдс“[12].

Желудникот на алигаторот често содржи гастролити. Функцијата на овие камења е дробење на храната што помага при дигестијата. Ова е доста важо, бидејќи алигаторите го голтаат целиот плен.

Сезоната на парење започнува на пролет. Иако алигаторите немаат гласни жици, мажјаците рикаат гласно за да ги привлечат женките и да ги предупредат останатите мажјаци. Овие рикања ги произведуваа со воздух кој го вдишуват во белите дробови а потоа го ипуштаат во испрекинати интервали.

Мажјаците употребуваат и инфразвук за време на сезоната за парење. Додека нивната глава и опаш се над водата а телото е нурнато, водата над грбот прска поради нивното инфразвучно рикање, и ова се нарекува „танц на водата“.[1]

Женките градат гнезда од растенија и кал во близина на вода. Во нив положуваат 20 до 50 јајца, по големина слични на гускините. Oва ги разликува од нилските крокодили, кои јајцата ги положуваат во дупки[2]. Температурата на која се наоѓаат јајцата за време на периодот на инкубација е одлучувачки фактор за полот на младите алигатори. Доколку температурата е 32,2 - 33,8 °C се развиваат машки, а доколу е 27,7 – 30 °C се развиваат женски. Доколу температураат е помеѓу, тогаш леглото е мешано, односно има и машки и женки алигатори. Мајката останува близу до гнездото за време на периодот на инкубација кој трае 65 дена и го заштитува од предатори. Кога младите почнуваат да излегуваат од јајцата испуштаат високо-фрекфентни крикови, со кои ја повикуваат мајката да го откопа гнездото.

Младенчињата се морфолошки идентични со родителите, и имаат жолти пруги околу нивните тела. По излегувањето од јајцата тие се упатуваат директно кон водата. Првите неколку дена живеат на резервите од жолчка кои ги имаат во стомаците. Мајката се грижи за младите во следните 5 месеци.

Алигаторите достигнуваат зрелост за парење на возраст помеѓу 8 и 13 години, кога се долги 1,8 - 2,1 метри. Од оваа возраст, ниниот раст станува побавен. Најстарите мажјаци кои имаат 30 или повеќе години можат да пораснат и до должина од 4,85 метри[13] и да тежат до 510 килограми.

Алигаторите се способни да убијат човек, но генерално се доста претпазливи и не ги гледаат луѓето како потенцијален плен. Каснувањето од алигатор е сериозна повреда најмногу поради опасноста од инфекција. Неадекватен третман на ваквите рани може да резултира со сериозни инфекции поради кои е неопходна ампутација на екстремитетот. Опашката на алигаторот е исто така моќно оружје со кое може да бутне човек на земја и да крши коски. Алигаторите се родители кои се однесуваат заштитнички спрема нивните млади, и напаѓаат било што што ќе се доближи премногу или претставува закана.

Ов 1948 година, регистрирани се повеќе од 275 неиспровоцирани напади на луѓе во Флорида, од кои најмалку 17 резултирале со смрт[14]. За време на 70тите, 80тите и 90тите години, имало само 9 фатални напади во САД, но алигаторите убиле 12 луѓе од 2001 до 2007 година.

Одгледувањето на алигатори е во вистински пораст на Флорида, во Тексас, во Џорџија и во Луизијана. Овие три држави годишно произведуваат околу 45 000 кожи од алигатор. Овие кожи достигнуваат висока цена на пазарот, па така кожа со должина од 1,8-2 метри достигнува цена од 300 долари. Производството на месо од алигатор исто така е доста популарно, па годишно се произведуваат и до 140 тони. Според оделот за земјоделство на Флорида, 100 грама месо од алигатор има 240 калории[15].

Низ историјата, алигаторите биле изумрени во многу делови од нивната распространетост поради прекумерниот лов и загубата на природното живеалиште, па така пред 30тина години луѓето мислеле дека овој вид нема никогаш да закрепне. Во 1967 година, американскиот алигатор е ставен на листата на загрозени видови, со што се сметало дека е во опасност од изумирање на сите територии на кои бил распространет.

Заедничките напори на „United States Fish and Wildlife Service“ државната агенција во САД, и формираните одгледувачки фарми помогнале за спасување на овој вид. Ловот на алигаторот станал забранет со закон, што овозможило зголемување на бројот на индивидуите во природата. Постојат и програми за набљудување со кои се следи зголемувањето на популациите. Во 1987 година, агенцијата објавува дека бројноста на американскиот алигатор е стабилизирана и полека го трга од листата на загрозени видови.

|date= (помош) Американскиот алигатор (Alligator mississippiensis) е еден од двата преживеани видови на алигатори, род од фамилијата Alligatoridae. Американскиот алигатор живее само на територијата на југоисточен САД, каде ги населува мочурливите земјишта. Овој вид е поголем од другиот преживен вид на алигатор – кинескиот алигатор.

The American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), sometimes referred to colloquially as a gator or common alligator, is a large crocodilian reptile native to the Southeastern United States. It is one of the two extant species in the genus Alligator, and is larger than the only other living alligator species, the Chinese alligator.

The American alligator is the largest reptile in North America. Adult male American alligators measure 3.4 to 4.6 m (11.2 to 15.1 ft) in length, and can weigh up to 453 kg (1,000 lb), with unverified sizes of up to 5.84 m (19.2 ft) and weights of 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) making it the second largest member of the family Alligatoridae, after the black caiman. Females are smaller, measuring 2.6 to 3 m (8.5 to 9.8 ft) in length.[5][6][7][8][9] The American alligator inhabits subtropical and tropical freshwater wetlands, such as marshes and cypress swamps, from southern Texas to North Carolina.[10] It is distinguished from the sympatric American crocodile by its broader snout, with overlapping jaws and darker coloration, and is less tolerant of saltwater but more tolerant of cooler climates than the American crocodile, which is found only in tropical and warm subtropical climates.

American alligators are apex predators and consume fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. Hatchlings feed mostly on invertebrates. They play an important role as ecosystem engineers in wetland ecosystems through the creation of alligator holes, which provide both wet and dry habitats for other organisms. Throughout the year (in particular during the breeding season), American alligators bellow to declare territory, and locate suitable mates.[11] Male American alligators use infrasound to attract females. Eggs are laid in a nest of vegetation, sticks, leaves, and mud in a sheltered spot in or near the water. Young are born with yellow bands around their bodies and are protected by their mother for up to one year.[12]

The conservation status of the American alligator is listed as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Historically, hunting had decimated their population, and the American alligator was listed as an endangered species by the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Subsequent conservation efforts have allowed their numbers to increase and the species was removed from endangered status in 1987. The species is the official state reptile of three states: Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

The American alligator was first classified by French zoologist François Marie Daudin as Crocodilus mississipiensis in 1801. In 1807, Georges Cuvier created the genus Alligator;[13] the American alligator and the Chinese alligator are the only extant species in the genus. They are grouped in the family Alligatoridae with the caimans. The superfamily Alligatoroidea includes all crocodilians (fossil and extant) that are more closely related to the American alligator than to either the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) or the gharial (Gavialis gangeticus).[14]

Members of this superfamily first arose in the late Cretaceous, about 100–65 million years ago (Mya). Leidyosuchus of Alberta is the earliest known fossil, from the Campanian era 83 to 72 Mya. Fossil alligatoroids have been found throughout Eurasia, because bridges across both the North Atlantic and the Bering Strait connected North America to Eurasia about 66 to 23 Mya.

Alligators and caimans split in North America during the late Cretaceous, and the caimans reached South America by the Paleogene, before the closure of the Isthmus of Panama during the Neogene period, from about 23 to 2.58 Mya. The Chinese alligator likely descended from a lineage that crossed the Bering land bridge during the Neogene. Fossils identical to the existing American alligator are found throughout the Pleistocene, from 2.5 million to 11.7 thousand years ago.[15] In 2016, a Miocene (about 23 to 5.3 Mya) fossil skull of an alligator was found at Marion County, Florida. Unlike the other extinct alligator species of the same genus, the fossil skull was virtually indistinguishable from that of the modern American alligator. This alligator and the American alligator are now considered to be sister taxa, meaning that the A. mississippiensis lineage has existed in North America for over 8 million years.[16]

The alligator's full mitochondrial genome was sequenced in the 1990s, and it suggests the animal evolved at a rate similar to mammals and greater than birds and most cold-blooded vertebrates.[17] However, the full genome, published in 2014, suggests that the alligator evolved much more slowly than mammals and birds.[18]

Domestic American alligators range from long and slender to short and robust, possibly in response to variations in factors such as growth rate, diet, and climate.

The American alligator is a relatively large species of crocodilian. On average, it is the largest species in the family Alligatoridae, with only the black caiman being possibly larger.[19] Weight varies considerably depending on length, age, health, season, and available food sources. Similar to many other reptiles that range expansively into temperate zones, American alligators from the northern end of their range, such as southern Arkansas, Alabama, and northern North Carolina, tend to reach smaller sizes. Large adult American alligators tend to be relatively robust and bulky compared to other similar-length crocodilians; for example, captive males measuring 3 to 4 m (9 ft 10 in to 13 ft 1 in) were found to weigh 200 to 350 kg (440 to 770 lb), although captive specimens may outweigh wild specimens due to lack of hunting behavior and other stressors.[20][21]

Large male American alligators reach an expected maximum size up to 4.6 m (15 ft 1 in) in length and weighing up to 453 kg (1,000 lb), while females reach an expected maximum of 3 m (9 ft 10 in).[5][6] However, the largest free-ranging female had a total length of 3.22 m (10 ft 7 in) and weighed 170 kg (370 lb).[22] On rare occasions, a large, old male may grow to an even greater length.[23][24]

During the 19th and 20th centuries, larger males reaching 5 to 6 m (16 ft 5 in to 19 ft 8 in) were reported.[25] The largest reported individual size was a male killed in 1890 on Marsh Island, Louisiana, and reportedly measured at 5.84 m (19 ft 2 in) in length, but no voucher specimen was available, since the American alligator was left on a muddy bank after having been measured due to having been too massive to relocate.[24] If the size of this animal was correct, it would have weighed about 1,000 kg (2,200 lb).[26] In Arkansas, a man killed an American alligator that was 4.04 m (13 ft 3 in) and 626 kg (1,380 lb).[27] The largest American alligator ever killed in Florida was 5.31 m (17 ft 5 in), as reported by the Everglades National Park, although this record is unverified.[28][29] The largest American alligator scientifically verified in Florida for the period from 1977 to 1993 was reportedly 4.23 m (13 ft 11 in) and weighed 473 kg (1,043 lb), although another specimen (size estimated from skull) may have measured 4.54 m (14 ft 11 in).[20] A specimen that was 4.5 m (14 ft 9 in) long and weighed 458.8 kg (1,011.5 lb) is the largest American alligator killed in Alabama and has been declared the SCI world record in 2014.[30][31]

American alligators do not normally reach such extreme sizes. In mature males, most specimens grow up to about 3.4 m (11 ft 2 in) in length, and weigh up to 360 kg (790 lb),[7] while in females, the mature size is normally around 2.6 m (8 ft 6 in), with a body weight up to 91 kg (201 lb).[8][9] In Newnans Lake, Florida, adult males averaged 73.2 kg (161 lb) in weight and 2.47 m (8 ft 1 in) in length, while adult females averaged 55.1 kg (121 lb) and measured 2.22 m (7 ft 3 in).[43] In Lake Griffin State Park, Florida, adults weighed on average 57.9 kg (128 lb).[44] Weight at sexual maturity per one study was stated as averaging 30 kg (66 lb) while adult weight was claimed as 160 kg (350 lb).[45]

There is a common belief stated throughout reptilian literature that crocodilians, including the American alligator, exhibit indeterminate growth, meaning the animal continues to grow for the duration of its life. However, these claims are largely based on assumptions and observations of juvenile and young adult crocodilians, and recent studies are beginning to contradict this claim. For example, one long-term mark-recapture study (1979–2015) done at the Tom Yawkey Wildlife Center in South Carolina found evidence to support patterns of determinate growth, with growth ceasing upon reaching a certain age (43 years for males and 31 years for females).[46]

While noticeable in very mature specimens, the sexual dimorphism in size of the American alligator is relatively modest among crocodilians.[47] For contrast, the sexual dimorphism of saltwater crocodiles is much more extreme, with mature males nearly twice as long as and at least four times as heavy as female saltwater crocodiles.[48] Given that female American alligators have relatively higher survival rates at an early age and a large percentage of given populations consists of immature or young breeding American alligators, relatively few large mature males of the expected mature length of 3.4 m (11 ft 2 in) or more are typically seen.[49]

Dorsally, adult American alligators may be olive, brown, gray, or black. However, they are on average one of the most darkly colored modern crocodilians (although other alligatorid family members are also fairly dark), and can be reliably be distinguished by color via their more blackish dorsal scales against crocodiles.[23] Meanwhile, their undersides are cream-colored.[50] Some American alligators are missing or have an inhibited gene for melanin, which makes them albino. These American alligators are extremely rare and almost impossible to find in the wild. They could only survive in captivity, as they are very vulnerable to the sun and predators.[51]

American alligators have 74–80 teeth.[25] As they grow and develop, the morphology of their teeth and jaws change significantly.[52] Juveniles have small, needle-like teeth that become much more robust and narrow snouts that become broader as the individuals develop.[52] These morphological changes correspond to shifts in the American alligators' diets, from smaller prey items such as fish and insects to larger prey items such as turtles, birds, and other large vertebrates.[52] American alligators have broad snouts, especially in captive individuals. When the jaws are closed, the edges of the upper jaws cover the lower teeth, which fit into the jaws' hollows. Like the spectacled caiman, this species has a bony nasal ridge, though it is less prominent.[25] American alligators are often mistaken for a similar animal: the American crocodile. An easy characteristic to distinguish the two is the fourth tooth. Whenever an American alligator's mouth is closed, the fourth tooth is no longer visible. It is enclosed in a pocket in the upper jaw.

Adult American alligators held the record as having the strongest laboratory-measured bite of any living animal, measured at up to 13,172 N (1,343.2 kgf; 2,961 lbf). This experiment had not been, at the time of the paper published, replicated in any other crocodilians, and the same laboratory was able to measure a greater bite force of 16,414 N (1,673.8 kgf; 3,690 lbf) in saltwater crocodiles;[53][54] notwithstanding this very high biting force, the muscles opening the American alligator's jaw are quite weak, and the jaws can be held closed by hand or tape when an American alligator is captured. No significant difference is noted between the bite forces of male and female American alligators of equal size.[52] Another study noted that as the American alligator increases in size, the force of its bite also increases.[55]

When on land, an American alligator moves either by sprawling or walking, the latter involving the reptile lifting its belly off the ground. The sprawling of American alligators and other crocodylians is not similar to that of salamanders and lizards, being similar to walking. Therefore, the two forms of land locomotion can be termed the "low walk" and the "high walk". Unlike most other land vertebrates, American alligators increase their speed through the distal rather than proximal ends of their limbs.[56] In the water, American alligators swim like fish, moving their pelvic regions and tails from side to side.[57] During respiration, air flow is unidirectional, looping through the lungs during inhalation and exhalation;[58] the American alligator's abdominal muscles can alter the position of the lungs within the torso, thus shifting the center of buoyancy, which allows the American alligator to dive, rise, and roll within the water.[59]