en

names in breadcrumbs

Birds of prey and carnivorous mammals, as well as snakes and large lizards may prey on pteropodids. Pteropodids tend to have fewer predators on islands. However, there have been several cases of introductions of non-native, arboreal snakes which have decimated pteropodid populations.

Pteropodids rely heavily on vision and olfaction when navigating and foraging. Intraspecific communication is often vocal. In some species, such as Pteropus poliocephalus, vocal signaling may be associated with specific motor activities which enhance the meaning of the vocal signal. In species such as Eidolon helvum, sexually dimorphic sebaceous glands which are larger in males may provide olfactory behavioral cues.

Communication Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; ultrasound ; chemical

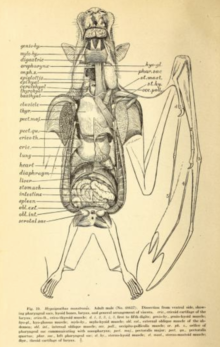

The head and body length of pteropodids varies from 50 mm to 406 mm. Despite size, many characteristics are shared among genera. A relatively long rostrum (pronounced in nectarivores), large eyes, and simple external ears give members of this family a dog or fox-like appearance (hence “flying fox”). The genera Nyctimene and Paranyctimene are exceptions in that they contain tubular nostrils that project from the upper surface of the snout. On the skull, postorbital processes are present over the orbital region. The palatine extends posterior to nearly cover the presphenoid. No more than two upper and two lower incisors are present in adults, otherwise cheek and canine dentition varies between species. The tongue is highly protrusible in nectar feeding bats and often complex with terminal papillae.

The chest is robust, comprised of the down-thrusting pectoralis and serratus muscles. The articulating regions of the humerus never come into contact with the scapula, which differs from a locking mechanism that occurs in the shoulder joint of other bat groups. The second digit is relatively independent from the third digit and contains a vestigial claw that adorns the leading edge of the wing.

Modifications for hanging include a relocation of the hip socket. The acetabulum is shifted upward and dorsally, and articulates with a large headed femur for a wider range of motion. In contrast to most other mammal orders, the legs cannot be positioned in a straight line under the body. In conjunction with large claws on their feet, pteropodids use a tendon-ratchet system that allows them to hang without prolonged muscular contraction. The legs manipulate a primitive uropatagium during flight. Aside from Notopteris, most species are tailless or with just a spicule of a tail.

Several species of Pteropodidae demonstrate sexual dimorphism. Males of Hypsignathus monstrosus have rather outlandish facial features, while females have the conservative fox-like look. Males of the genus Epomops have distinctive white patches in association with a glandular membrane on their shoulders, whereas females do not. Considering the whole family, males are generally larger than females. The penis of all pteropodids is a pendant and freely movable organ, resembling that of Primates. Juveniles are typically naked or have a velvety coat that is darker than adult pelage.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: sexes alike; male larger; sexes colored or patterned differently; ornamentation

Pteropodids have been known to live at least 30 years, both in captivity and in the wild.

Pteropodids typically occur in primary or maturing secondary forests. A few species inhabit savannah habitats where they roost in bushes and low trees. Over half of the 41 genera are made up of species that roost in trees. Gregarious species roost on the open branches of large, canopy-emergent trees. Pteropodids that roost singly or in small groups can be found in dead palm leaves, aerial roots, and even arboreal termite nests. These bats also tend to have cryptic coloration and wrap themselves with their wings in order to resemble dead leaves. In one species, Cynopterus sphinx, individuals construct tents by chewing folds in palm leaves. Caves, cliff walls, mines, and the eaves of buildings also serve as roosting locations for species in 17 genera. Most cave-dwelling species are limited to the lit areas near the opening, while members of the genus Rousettus are able to navigate the darker regions using crude echolocation.

Flowering plants are essential to the diet of pteropodid species; therefore, flying foxes mostly use woodlands or orchards for food. Canopy emergent fruiting trees, such as fig and baobab trees, are frequently used as a food source. The flowers of baobab trees have a strong fragrance and are located on the crown of the tree, which makes them easily accessible to bats (a flower syndrome known as chiropterophily). Many pteropodid species are found in coastal areas and drink salt water in order to supplement nutrients lacking in their diet.

A few species are migratory. Eidolon helvum individuals gather in large numbers and migrate hundreds of kilometers northward with seasonal rains, only to return to southern Africa at the end of the rainy season. Pteropus scapulatus populations make major, and somewhat erratic movements within Australia, following the flowering periods of Eucalyptus trees. Many species of Pteropus roost on islands and make daily migrations to the mainland for foraging. Some species range from sea level to 2500 m, yet little is known about any significant elevational migrations.

Habitat Regions: tropical ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: savanna or grassland ; forest ; rainforest

Other Habitat Features: suburban ; agricultural ; riparian ; estuarine

Pteropodidae has a tropical and subtropical distribution in the Old World (eastern hemisphere). Species are found as far north as the eastern Mediterranean, continuing along the southern coast of the Arabian Peninsula and across South Asia. Species are found as far south as South Africa, the islands of the Indian Ocean, and to the northern and western coasts of Australia. The longitudinal range reaches from the Atlantic coast of Africa to the islands of the western Pacific. Pteropodids are absent from northwest Africa, southwest Australia, a majority of the Palearctic region, and all of the Western Hemisphere.

Biogeographic Regions: palearctic (Native ); oriental (Native ); ethiopian (Native ); australian (Native ); oceanic islands (Native )

Pteropodids are frugivorous and nectarivorous. Some species also eat flowers of the plants they visit. Foraging habits are not well documented, though many species of the genus Pteropus rely heavily on figs. Many species rely on broad array of resources, though there may be a functional dichotomy between large species that rely heavily on canopy resources and smaller species that can use understory resources. Some larger species can use the claws on their thumbs and second digits to climb into the understory and seek out fruit that is hidden or inaccessible by flight.

Primary Diet: herbivore (Frugivore , Nectarivore )

Pteropodids provide important pollination and seed dispersal services to a wide range of plants. On islands in the south Pacific, pteropodids are the principle pollinators and dispersers of plants. Many plants have adaptations specifically for seed dispersal and pollination by bats, such as fruiting or flowering at the ends of branches and at bat accessible locations in the canopy. Eidolon dupreanum has been shown to likely be the sole pollinator of the baobab tree Adansonia suarezensis in Madagascar.

Ecosystem Impact: disperses seeds; pollinates

Larger species of pteropodids are hunted for their meat. Both subsistence and commercial hunting of Pteropus species have been reported. Consumer demand for Pteropus species on the island of Guam has been so great that it has resulted in the extinction of at least one species in the Pacific region. Flying foxes are also important in the dispersal and pollination of economically important plants. They attract tourists in some areas and produce accumulations of guano that can be used as fertilizer.

Positive Impacts: food ; ecotourism ; produces fertilizer; pollinates crops

Many crop species are attractive food sources for pteropodids. Because cultivars are often developed from wild species, these commercial crops have the same characteristics that wild plants evolved to attract bats to their fruit. Fruit growers have experimented with visual, audio, and olfactory deterrents as well as electric wire to keep pteropodids from eating their crops. Pteropodids may also be dispersers of invasive plant species, as they consume crops introduced for cultivation and may disperse the seeds into natural habitat. Pteropodids have been indicated as reservoirs for a variety of viruses such as Ebola and other viruses in the family Paramyxoviridae. Hendra virus, Menangle virus, and Nipah virus have all been linked to pteropodids.

Negative Impacts: injures humans (carries human disease); crop pest

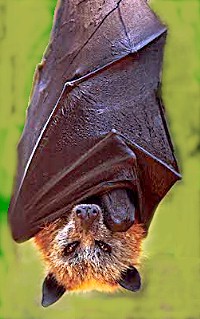

Members of Pteropodidae are known colloquially as the flying foxes, or Old World fruit bats. The family is composed of 41 genera and about 170 species. The most species-rich genus in the family is Pteropus with 59 species, many of which are island endemics. Body and wing size ranges from small (37 mm forearm length) to large (220 mm forearm length). The family boasts the largest bats in the world. Pteropus vampyrus individuals have a wingspan of up to 1.7 m. Pteropus giganteus individuals have a comparable wingspan but a greater mass, with males weighing between 1.3 and 1.6 kg. Pteropodids are strictly vegetarian, foraging for fruits, nectar, and pollen using their sight and a sensitive olfactory system. Bats of the genus Rousettus use tongue clicks as a crude form of echolocation while navigating in the dark. Some species are migratory, covering vast distances, while others have more moderate home ranges. Eidolon helvum individuals aggregate in numbers reaching the hundreds of thousands, yet many species roost with only a few conspecifics. Members of Pteropodidae service the ecosystems they inhabit by playing important roles as pollinators and seed dispersers.

Many factors threaten pteropodids throughout their range. Human activities have decimated populations of certain species directly through hunting or indirectly through habitat destruction. In Asia and Australia, deforestation is the most important contributor to pteropodid population decline. Some species are vulnerable to typhoons and hurricanes which may destroy roosting habitat on islands. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species lists 5 species as recently extinct, 10 species as critically endangered, 19 species as endangered, 15 species as near threatened, and 39 species as vulnerable, suggesting that nearly half of all pteropodid species face significant threats to population viability.

Mating behavior in pteropodids is highly variable, and much is unknown. The males of one genus (Hypsignathus) set up lekking territories twice a year and draw in females with unique vocalizations and wing-flapping displays. Male epauletted fruit bats (genus Epomophorus) often display their concealed epaulets (hair tufts near the shoulder) and emit courting calls to attract females. Many species form harems consisting of 1 dominant male and up to 37 females, while bachelor males roost separately.

Mating System: polygynous ; polygynandrous (promiscuous)

While most bats have one reproduction event per year, many pteropodids are polyestrous, with two seasonal cycles corresponding to the annual wet and dry seasons. Usually one young is born per pregnancy, but twins are not uncommon. Upon fertilization, ova implantation in the uteri can be immediate or delayed, probably in response to the environment. Development of the embryo (once implanted) may also be delayed, probably to ensure birth at a time when fruit is available during the rainy seasons. One species, Macroglossus minimus, exhibits asynchronous breeding and sperm storage, suggesting the importance of birth during an optimal (rainy) season.

Pregnant females usually leave social roosts to form nursery groups with other pregnant females. Females in nursery roosts form their own social network and take care of each other through mutual grooming. Gestation periods usually lasts 4 to 6 months, but can be longer if implantation is delayed. Birth patterns of pteropodids have been widely studied and usually occur during the wet periods both in the northern latitudes (February to April) and the southern latitudes (August to November). Species that are polyestrous will give birth during both of these rainy seasons. It is predicted that birth during these seasons yields high survival rates because lactation occurs when fruit availability is at a maximum. Birth is followed by postpartum estrous and subsequent mating. After weaning, young may stay with their mothers up to 4 months. Sexual maturity in juveniles is reached by 2 years old or earlier. Female sexual maturity is reached earlier than in males.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; viviparous ; delayed implantation ; post-partum estrous

Female pteropodids are primarily responsible for rearing the young. Lactation lasts anywhere from 7 weeks to 4 months, and the mother may care for her young slightly longer. In one genus (Dyacopterus), males with functional mammary glands have been reported lactating, which suggests the sharing of juvenile care among both parents.

Parental Investment: altricial ; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-independence (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female)

İriqanadlar (lat. Megachiroptera və ya lat. Pteropodidae) — yarasalar dəstəsinin aid heyvan yarımdəstəsi.

Bu yarımdəstəyə yeğanə iriqanadkimilər (Pteropidae) fəsiləsi daxildir. Fəsilənin Pteropus və Rousettus cinslərini, bəzən isə bütün nümayəndələrini uçan itlər adlandırırlar.

Yarasalardan fərqli olaraq, iriqanadlar böyük ölçülərə malik olurlar. Onların bədənləri 42 sm, qanadlarının ölçüləri 1,7 m-ə (iriqanad) çatır. Buna baxmayaraq, bədənləri 5-6 sm, qanadlarının uzunluğu 24 sm-ə çatan kiçik ölçülü növləri də var. Kütlələri 15-900 q arasında dəyişir. Quyruqları qısa, inkişaf etməmiş olur, yaxud, ümumiyyətlə olmur. Ancaq uzunquyruq iriqanadda (Notopteris) quyruğu nisbətən uzun olur. Qanadın II barmağı uc hissəsi olmaqla, adətən caynaqlı olur.

İriqanadlar (lat. Megachiroptera və ya lat. Pteropodidae) — yarasalar dəstəsinin aid heyvan yarımdəstəsi.

Bu yarımdəstəyə yeğanə iriqanadkimilər (Pteropidae) fəsiləsi daxildir. Fəsilənin Pteropus və Rousettus cinslərini, bəzən isə bütün nümayəndələrini uçan itlər adlandırırlar.

Yarasalardan fərqli olaraq, iriqanadlar böyük ölçülərə malik olurlar. Onların bədənləri 42 sm, qanadlarının ölçüləri 1,7 m-ə (iriqanad) çatır. Buna baxmayaraq, bədənləri 5-6 sm, qanadlarının uzunluğu 24 sm-ə çatan kiçik ölçülü növləri də var. Kütlələri 15-900 q arasında dəyişir. Quyruqları qısa, inkişaf etməmiş olur, yaxud, ümumiyyətlə olmur. Ancaq uzunquyruq iriqanadda (Notopteris) quyruğu nisbətən uzun olur. Qanadın II barmağı uc hissəsi olmaqla, adətən caynaqlı olur.

Pteropodidae zo ur c'herentiad e rummatadur ar bronneged, ennañ eskell-kroc'hen.

Pteropodidae zo ur c'herentiad e rummatadur ar bronneged, ennañ eskell-kroc'hen.

Kaloni (Megachiroptera) jsou jeden ze dvou podřádů letounů, což je skupina savců, kam dále patří například netopýři. Zařazuje se k nim jediná čeleď, kaloňovití (Pteropodidae). Přes své velké rozměry jsou kaloni velmi lehcí a i ti největší kaloni dosahují hmotnosti jen pod dva kilogramy.

Tělo kaloňů je podobné tělu netopýrů, ale jeho hlava se nápadně podobá liščí hlavě.

Kaloni zajišťují u několika stovek rostlin přenos pylu (zoogamie).

Kaloni jsou především býložravci a živí se sladkými plody. Za potravou vyletují ve dne, v hejnech nebo osamoceně, pak se usadí na ovocném stromě a požírají plody. Stonky a semena opatrně vyplivují.

Někteří kaloni dali dokonce přednost požírání nektaru a pylu z tropických květin, které mají k dispozici po celý rok. Tito letouni létají v hejnech asi po dvaceti, poté krouží kolem rostliny a jednotlivě vystřelují dlouhý jazyk, aby ochutnali nektar. Jakmile je potrava vyčerpána, hejno se přemístí k další rostlině. Na rozdíl od jiných kaloňů tito nehibernují, ale létají celý rok a stále se krmí. Pomáhají tak opylovat rostliny a usnadňují tvorbu semen.

Kaloni využívají k orientaci svoje velké oči spolu s echolokací. Ultrazvuk vysílají pomocí jazyku, kterým klikají. Kaloni sekundárně ztratili laryngeální echolokaci.

Některé druhy kaloňů stojí pravděpodobně za původem obávaného ebola viru, způsobující krvácivou horečku (nejsmrtelnější typy viru mají až 90 % smrtnost). K přenosu na primáty došlo možná kontaminovaným ovocem. Také virus Marburg je s nimi spojován.

172 druhů kaloňů žije v tropických a subtropických oblastech Asie, Oceánie a Afriky. Mezi ně patří například:

Kaloni (Megachiroptera) jsou jeden ze dvou podřádů letounů, což je skupina savců, kam dále patří například netopýři. Zařazuje se k nim jediná čeleď, kaloňovití (Pteropodidae). Přes své velké rozměry jsou kaloni velmi lehcí a i ti největší kaloni dosahují hmotnosti jen pod dva kilogramy.

Tělo kaloňů je podobné tělu netopýrů, ale jeho hlava se nápadně podobá liščí hlavě.

Kaloni zajišťují u několika stovek rostlin přenos pylu (zoogamie).

Storflagermus er en underorden af flagermus. Der eksisterer kun en enkelt familie, kaldet flyvende hunde (Pteropodidae). De fleste (men ikke alle) arter er større end småflagermus: De mindste er 6 cm lange, de store bliver 40 cm lange og har et vingefang på 1,5 m. Disse kæmper kan veje mere end et kilogram.

Flyvende hunde lever af frugt og nektar fra blomster, i stedet for insekter som småflagermus. Den flyvende hund har fået sit navn, fordi hovedet ligner en hunds. Småflagermus har et hoved, der mere ligner en lille gnavers hoved. De flyvende hunde bruger fortrinsvis syn og lugtesans til at orientere sig med.

Flyvende hunde tilbringer dagen sovende i kolonier på op til 10.000 individer. I klippehuler eller i frugtbærende træer hænger de i fødderne med hovedet nedad og vingerne slået sammen om kroppen. Når mørket falder på, letter alle de flyvende hunde på én gang og begiver sig i samlet trop ud for at finde modne frugter.

Ungerne sidder de første måneder på maven af hunnen og dier hos hende. Senere bliver de hægtet af i træerne, når hunnen om natten skal ud og lede efter føde. Når ungerne er omkring 6 måneder, følger de med de voksne ud for at finde føde.

Kun en enkelt art, den ægyptiske flyvende hund (Rousettus aegyptiacus), kan benytte sig af ekkolokalisering ligesom småflagermus.[1]

Underordnen Megachiroptera omfatter kun en enkelt familie, Pteropodidae med i alt cirka 186 nulevende arter.

Eksempel på arter:

Storflagermus er en underorden af flagermus. Der eksisterer kun en enkelt familie, kaldet flyvende hunde (Pteropodidae). De fleste (men ikke alle) arter er større end småflagermus: De mindste er 6 cm lange, de store bliver 40 cm lange og har et vingefang på 1,5 m. Disse kæmper kan veje mere end et kilogram.

Die Flughunde (Pteropodidae) sind eine Säugetierfamilie aus der Ordnung der Fledertiere (Chiroptera). Sie sind die einzige Familie der Überfamilie Pteropodoidea und bilden zusammen mit den Hufeisennasenartigen (Rhinolophoidea) die Unterordnung Yinpterochiroptera.[1] Die Familie umfasst rund 40 Gattungen mit knapp 200 Arten.

Flughunde sind in tropischen und subtropischen Regionen in Afrika (einschließlich Madagaskar und den Seychellen), im Indopazifik, dem südlichen Asien, Australien und dem westlichen Ozeanien verbreitet. Am Rande der europäischen Fauna ist lediglich der Nilflughund in der Südtürkei sowie auf der Insel Zypern anzutreffen. Sie gehören geographisch zu Asien.

Flughunde stellen die größten Fledertierarten dar. Der Kalong erreicht eine Flügelspannweite von bis zu 170 Zentimetern und manche Arten haben eine Kopfrumpflänge von bis zu 40 Zentimetern. Allerdings sind viele Arten kleiner und die größten Fledermaus-Arten sind deutlich größer als die kleinsten Flughunde-Arten.

Im Körperbau entsprechen die Flughunde den übrigen Fledertieren, die Flugmembran wird von den verlängerten zweiten bis fünften Fingern gespannt und reicht bis zu den Fußgelenken. Allerdings haben die meisten Flughunde – mit Ausnahme des Langschwanzflughundes (Notopteris) – keinen oder nur einen sehr kurzen Schwanz. Auch das Uropatagium (die Schwanzflughaut) ist nur ein schmaler Streifen entlang der Hinterbeine. Ein weiteres Unterscheidungsmerkmal zu den Fledermäusen ist eine Kralle am zweiten Finger, die bei den meisten Flughundarten vorhanden ist, bei den Fledermäusen jedoch fehlt.

Die Gesichter der Flughunde sind einfach gebaut. Die Nasen besitzen keine Nasenblätter und ihre kleinen, ovalen Ohren keinen Tragus. Die Schnauzen sind oft verlängert, was zu dem hundeartigen Aussehen und ihrem deutschen Namen geführt hat.

Flughunde sind in erster Linie dämmerungs- oder nachtaktiv. Sie legen bei der Nahrungssuche oft weite Strecken zurück, tagsüber schlafen sie kopfüber hängend. Im Gegensatz zu Fledermäusen findet man Flughunde oft auf Bäumen an exponierten Stellen hängend – in tropischen Regenwäldern bevorzugt auf den über das Kronendach ragenden „Urwaldriesen“.

Ein weiterer Unterschied zu den Fledermäusen ist das Fehlen der Echoortung – außer bei den Rosettenflughunden. Flughunde haben gut entwickelte Augen und einen ausgezeichneten Geruchssinn. Aufgrund des warmen Klimas in ihrem Verbreitungsgebiet halten sie keinen Winterschlaf. Während die größeren Arten oft in großen Gruppen zusammenleben, wobei sie große Kolonien mit bis zu 500.000 Tieren bilden können und ein komplexes soziales Verhalten entwickeln, sind die kleineren Arten eher Einzelgänger.

Flughunde ernähren sich pflanzlich, von Nektar, Pollen, Früchten und Blüten. Eine Reihe von Arten ist dadurch für die Vegetation wichtig, da sie beim Verzehr von Früchten Samen transportieren oder auch Blüten bestäuben (Chiropterophilie). Größere Kolonien vermögen so in einer Nacht mehrere hunderttausend Samen zu verbreiten, wie dies etwa bei den afrikanischen Palmenflughunden nachgewiesen wurde, wodurch Pflanzen wieder in bereits entwaldete Regionen gelangen können.[2]

Selbst der Geschlechtsakt wird kopfüber durchgeführt. Meistens bringen die Weibchen nur einmal im Jahr ein einzelnes Jungtier zur Welt. Trächtige Weibchen sondern sich oft von den Männchen ab und bilden Wochenstuben, in denen sie den Nachwuchs großziehen. Flughunde sind relativ langlebige Tiere, sie erreichen ein Alter von bis zu 30 Jahren.

Acht Arten sind laut IUCN ausgestorben, 22 weitere gelten als gefährdet oder stark gefährdet.

Der Hauptgrund für die Bedrohung der Arten ist die Zerstörung ihres Lebensraums durch Rodung der Wälder. Viele Arten sind darüber hinaus auf kleinen Inseln endemisch und daher besonders anfällig für Störungen des Ökosystems. Manche Arten werden vom Menschen als Schädlinge betrachtet, weil sie die Früchte in Obstplantagen fressen, oder sie werden ihres Fleisches wegen gejagt.

Die Regierung von Mauritius hat im Oktober 2015 beschlossen, 20 Prozent der Population von Pteropus niger zu töten, weil die Tiere angeblich die Ernte von Mangos und Litschis schädigen. Tierschützer und die Weltnaturschutzunion IUCN warnten, das könne die Art an den Rand des Aussterbens bringen.[3]

Ob die Fledertiere (Flughunde und Fledermäuse) monophyletisch sind, das heißt, sich aus einem gemeinsamen Vorfahren entwickelt haben, oder sich unabhängig voneinander entwickelten und nur ein Beispiel konvergenter Evolution darstellen, war längere Zeit umstritten. Heute geht man aber meist von der Monophylie der Fledertiere aus. Näheres siehe unter Systematik der Fledertiere.

Traditionell wurden die Flughunde in zwei Unterfamilien unterteilt: Den Eigentlichen Flughunden (Pteropodinae) stand eine Gruppe kleinerer Tiere gegenüber, die sich durch eine lange Zunge auszeichnen und sich vorwiegend von Nektar ernähren, diese wurden als Langzungenflughunde (Macroglossinae) bezeichnet. Jüngere Untersuchungen haben jedoch gezeigt, dass diese Einteilung nicht haltbar ist.

Die interne Systematik der Flughunde ist noch immer umstritten und Gegenstand zahlreicher Untersuchungen. Die folgende Einteilung in Gattungsgruppen basiert weitgehend auf der phylogenetischen Untersuchung von Kate E. Jones u. a.: A Phylogenetic Supertree of Bats.[4] Die Autoren verwenden für die Taxa keinen Rang im klassischen Sinn. Die Bezeichnung aller acht Gruppen als Tribus mit der Endung -ini (hier und in den verlinkten Artikeln) ist daher willkürlich gewählt. Manchmal findet man einzelne Gruppen auch im Rang einer Unterfamilie (-inae) oder einer Subtribus (-ina).

Die Entwicklungsgeschichte der Flughunde kann in folgendem Diagramm zusammengefasst werden:

Flughunde (Pteropodidae) N.N. N.N.Rosettenflughunde (Rousettini)

Epaulettenflughunde (Epomophorini)

Spitzzahnflughunde (Harpyionycterini)

Nacktrückenflughunde (Dobsoniini)

Eigentliche Flughunde (Pteropodini)

Röhrennasenflughunde (Nyctimenini)

Kurznasenflughunde (Cynopterini)

Die Flughunde (Pteropodidae) sind eine Säugetierfamilie aus der Ordnung der Fledertiere (Chiroptera). Sie sind die einzige Familie der Überfamilie Pteropodoidea und bilden zusammen mit den Hufeisennasenartigen (Rhinolophoidea) die Unterordnung Yinpterochiroptera. Die Familie umfasst rund 40 Gattungen mit knapp 200 Arten.

Kalong iku anggota bangsa lawa (Chiroptera) sing kagolong sajeroning familia Pteropodidae, siji-sijiné familia anggota subordo Megachiroptera. Tembaung "kalong" kerep dipigunakake kanggo ngganti tembung lawa sajeroning pacelathon sadina-dina, sanadyan kanthi ilmiah bab iki ora trep, amarga ora kabèh lawa iku kalong. Kalong iku kéwan hèrbivor, lan mung mangan woh-wohan utawa ngisep nektar saka kembang.

Letipsi obuhvataju podred Megachiroptera i jedinu porodicu Pteropodidae iz reda Chiroptera (šišmiši). Također se se označavaju i kao voćnim šišmiši ili šišmiši Starog svijeta, naročito rodovi Acerodon i Pteropus (leteće lisice).

Voćni šišmiši su ograničeni na Stari svijet, u tropskim i suptropskim područjima, u rasponu od istočnog Sredozemlja do ijužne Azije, a nema ih na sjeverozapadu Afrike i jugozapadnoj Australiji . U usporedbi s bubojednim šišmišma, voćni šišmiši su relativno velike i, uz neke iznimke, ne kreću se pomoću eholokacije. Oni su biljojedi, a za pronalaženje hrane, oslanjaju se na osjetljiva čula vida i mirisa.[1]

Većina voćnih šišmiša p su veće od bubojednih šišmiša ili Microchiroptera, ali također postoji i veliki broj malih voćnih šišmiša. Predstavnici najmanje vrste j su dugi oko 6 cm, a time i manji od nekih Microchiroptera, naprimjer, maurisijskog grobarskog šišmiša . Najveći doseže raspon krila od 1,7 m i težinu do 1,6 kg .Većina voćnih šišmiši imaju velike oči, dopuštajući im da se orijentiraju vizualno u sumrak i unutar špilje i šume. Njihov osjećaj za miris je odličan. Za razliku od , voće šišmalih šišmiša, ne koriste eholoukaciju (uz jednu iznimku, a to je je egipatski voćni šišmiš Rousettus egyptiacus, koji koristi piskav zvuk za navigaciju u spiljama).

Tjelesna građa svih šišmiša uglavnom ima sličan plan. Letnu kožicu se zateže produženim drugim do petim prstom doseže do gležnjeva. Međutim, većina ovih šišmiša uopće nema rep ili je veoma kratak (izuzetak su dugorepi šišmiši roda Notopteris). Repna letna kožica im je u vidu samo uske pruge duž unutrašnje strane zadnjih nogu. Od Microchiroptera (sitni šišmiši) razlikuju se po kandži koja se kod većine letipasa nalazi na vrhu drugog prsta, koju sitni šišmiši nemaju.[2][3][4][5]

Letipsi čine jedinu porodica (Pteropodidae) Chiroptera koja nije sposobna larinksa ispuštati zvuke za eholocinanje (na osnovu prijema odbijenog zvuka od tvrdog objekta). Eholokacija i let su evoluirali u ranim lozama šišmiša, ali se kasnije izgubila u porodici Pteropodidae. Šišmiši u rodu Rousettussu sposobni za primitivnu ehololokaciju klikovima pomoću jezika, a neke vrste su pokazale da stvaraju klikove slične onima eholokating šišmiša pomoću krila.[6][7][8][9]

I eholokacija i let su energetski skupi postupci za šišmiše. Priroda leta i eholokacijski mehanizam šišmiša omogućuje stvaranje eholokacijskih impulsa s minimalnim utroškom energije. Za energetska spajanje tih dvaju procesa se mislio da dopuštaju da se kod ovih šišmiša tazviju energetski skupi postupci leta. Gubitak eholokacije može biti i zbog odvajanja od bježanja i eholokacije letipasa. Povećana prosječna veličina tijela odnosu na ehholocirajuće šišmiše, sugerira da je veća veličina tijela ometa let pomoću eholokacije.

Letipsi su aktivni pretežno u sumrak i noću. U potrazi za hranom prelaze velike udaljenosti, a danju spavaju viseći glavom prema dolje. Za razliku od sitnih šišmiša, često ih se sreću na stablima na izloženim mjestima.[10]

U odnosu na Microchyroptera snalaženja u okolišu uznemaju sposobnost orijenracije pomoću ultrazvuka (izuzetak su rozetni velešišmiši (Rousettini), tj eholokacije. Vid im je relativno dobro a njuh i izvanredan. Ne padaju zimski san jer žive u toplim klimatima. Predstavnici krupnijih vrsta često žive u velikim grupama, u velikom kolonijama u kojima bude i do 500.000 jedinki s vrlo kompleksnim društvenim ponašanjem, dok su manje vrste uglavnom samotnjaci.

Unatoč tjelesnoj veličini, letipsi su potpuno bezopasni. Hrane se isključivo biljnom hranom, nektarom, polenom, voćem i cvjetovima. Čitav niz vrsta imaju izniman zčaj za biljni svijet, nakon konzumiranja plodova, raznose sjemenke voćki, a ze neke biljke su isključivi polinatori (oprašivači). To znači, da bi njihov nestanak istovremeno značio i nestanak vezanih vrsta biljaka.

Čak se i spolni odnos se kod letipasa odvija glavom prema dolje. Ženke, jednom godišnje, uglavnom kote po jedno mladunče. Skotne se odvajaju od mužjaka u skupine u kojima podižu podmladak. Veliki šišmiši su relativno dugovječni, a dožive i do 30 godina.

Šišmiši Starog svijeta žive u tropskim i suptropskim područjima Afrike (uključujući Madagaskar), južnoj Aziji, Australiji i zapadnoj Okeaniji. Nema ih u Europi, s izuzetkom egipatskog voćnog šišmiša (Rousettus aegyptiacus) na Kipru, ako se u ovom smislu Kipar može smatrati Europom.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23]

Veliki broj vrsta velikih šišmiša se uključuju u ugrožene. Glavni razlog je uništavanje njihovog okoliša, koje nastaje krčenjem šuma. Pored toga, mnoge malootočne vrste su endemske, pa su osobito osjetljive na smetnje u svom obitavalištu. Neke se smatraju štetočinama jer se hrane voćem s plantaža ili ih love radi mesa. Prema kriterijima Međunarodne unije za zaštitu prirode i prirodnih resursa (IUCN): International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources), osam vrsta je izumrlo, a još 22 se smatraju ugroženim ili jako ugroženim.

Dugo su nnogi naučnici vodili sporove oko toga, da li su sitni šišmiši i veliki šišmiši monofilijske grupe, što znači da li su se razvili od zajedničkih predaka, ili su primjer konvergentne evolucije. Danas preteže mišljenje da su monofilijske linije evolucije.

Tradicijski se letipsi dijele na dvije potporodice: prave (Pteropodinae) i grupu manjih životinja koje su obilježene dugačkim jezicim i pretežnom ishranom nektarom. Nazvani su velikim šišmišima dugog jezika (potporodica Macroglossinae). Novija istraživanja su pokazala, da takva podjela nije ispravna.[24]. Grupe su prilično proizvoljno svrstane i ne treba ih smatrati općeprihvaćenim naučnim stavom.

Naprimjer, tokom 1980-ih i 1990-ih, neki istraživači su predložili (prvenstveno na temelju vizuelne sličnosti) da su Megachiroptera zapravo u većoj mjeri povezani s primatima nego redom Microchiroptera, s dvije skupine šišmiša, dakle, koje su razviile let putem konvergencije. Međutim, nedavni priliv genetičkih studija više potvrđuje dugogodišnju tvrdnju da su svi šišmiši zaista članovi iste grane, Chiropštera. Druge studije su nedavno predložile da neke porodice Microchiroptera (možda i potkovočast šišmiši, mišorepi šišmiši i lažni vampiri) su pokazale da su evolucijski bliži voćnim šišmišima nego drugim pripadnicima reda Microhiroptera.[25][26]

Porodica Pteropodidae je podijeljena u sedam potporodica, sa 186 ukupnih sačuvanih vrsta, koje zastupa 44-46 rodova.

Letipsi obuhvataju podred Megachiroptera i jedinu porodicu Pteropodidae iz reda Chiroptera (šišmiši). Također se se označavaju i kao voćnim šišmiši ili šišmiši Starog svijeta, naročito rodovi Acerodon i Pteropus (leteće lisice).

Voćni šišmiši su ograničeni na Stari svijet, u tropskim i suptropskim područjima, u rasponu od istočnog Sredozemlja do ijužne Azije, a nema ih na sjeverozapadu Afrike i jugozapadnoj Australiji . U usporedbi s bubojednim šišmišma, voćni šišmiši su relativno velike i, uz neke iznimke, ne kreću se pomoću eholokacije. Oni su biljojedi, a za pronalaženje hrane, oslanjaju se na osjetljiva čula vida i mirisa.

Popo-matunda ni aina za popo wanaokula matunda hasa. Kibiolojia ni mamalia wa familia Pteropodidae, familia pekee ya nusuoda Megachiroptera katika oda Chiroptera, wanaofanana na panya au mbwa mdogo mwenye mabawa. Kwa kawaida spishi hizi ni kubwa kuliko zile za nusuoda Microchiroptera (popo-wadudu) lakini kuna spishi zilizo ndogo kulika spishi fulani za popo-wadudu. Yumkini spishi kubwa kabisa ni popo-bweha wa Uhindi aliye na uzito wa kg 1.6, urefu wa mwili wa sm 40 na urefu wa mabawa wa hadi m 1.5. Mabawa ya popo-bweha mkubwa yana urefu wa hadi m 1.6. Spishi ndogo kabisa ni popo-matunda mabawa-madoa aliye na uzito wa g 15 na urefu wa mwili wa sm 5-6. Popo-matunda hula matunda au mbochi. Wale wanaokula matunda husambaza spishi za miti na wale wanaokula mbochi huchavusha maua. Kama popo wote hata popo-matunda hukiakia usiko na hulala mchana. Wakilala wananing'inia juu chini na kujifunika kwa mabawa. Takriban spishi zote hulala mitini, lakini spishi kadhaa hulala ndani ya mapango.

Popo-matunda ni aina za popo wanaokula matunda hasa. Kibiolojia ni mamalia wa familia Pteropodidae, familia pekee ya nusuoda Megachiroptera katika oda Chiroptera, wanaofanana na panya au mbwa mdogo mwenye mabawa. Kwa kawaida spishi hizi ni kubwa kuliko zile za nusuoda Microchiroptera (popo-wadudu) lakini kuna spishi zilizo ndogo kulika spishi fulani za popo-wadudu. Yumkini spishi kubwa kabisa ni popo-bweha wa Uhindi aliye na uzito wa kg 1.6, urefu wa mwili wa sm 40 na urefu wa mabawa wa hadi m 1.5. Mabawa ya popo-bweha mkubwa yana urefu wa hadi m 1.6. Spishi ndogo kabisa ni popo-matunda mabawa-madoa aliye na uzito wa g 15 na urefu wa mwili wa sm 5-6. Popo-matunda hula matunda au mbochi. Wale wanaokula matunda husambaza spishi za miti na wale wanaokula mbochi huchavusha maua. Kama popo wote hata popo-matunda hukiakia usiko na hulala mchana. Wakilala wananing'inia juu chini na kujifunika kwa mabawa. Takriban spishi zote hulala mitini, lakini spishi kadhaa hulala ndani ya mapango.

Pteropodidae es un familia de Chiroptera.

Ang kalwang ay bumubuo sa subkurya ng Megachiroptera, at ang tanging pamilya nito na Pteropodidae ng order na Chiroptera (paniki). Ang mga ito ay tinatawag ding mga kalwang, o lalo na ang genera na Acerodon at Pteropus, na lumilipad na mga kalwang. Ang mga kalwang ay matatagpuan sa Amerika, Kanlurang Europa, hilagang-kanluran ng Aprika at timog-kanluran ng Australia.

This list is generated from data in Wikidata and is periodically updated by Listeriabot.

Edits made within the list area will be removed on the next update!

![]() Ang lathalaing ito ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

Ang lathalaing ito ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

La familha dels Pteropodidae amassa de ratapenadas generalament frugivòras. Aquesta familha foguèt creada per Gray en 1821.

Do Pteropodidae (Düütsk: Flughunde/Flederhunde "Flädderhuunde") sunt nai früünd mäd do Fläddermuuse, man jo hääbe (buute ju ägyptiske Oard Rousettus aegyptiacus) neen Echolot-Orientierenge. Dät rakt disse Dierte in Afrikoa, Suud-Asien, Australien, Wääst-Ozeanien un Zypern. Me kon do uk in n Zoo hoolde. Jo sunt ju eensichste Familie fon ju Unneroardenge Megachiroptera. In ju Fäksproake kwäd me deeruum, disse Unneroardenge is monotypisk.

Do Pteropodidae (Düütsk: Flughunde/Flederhunde "Flädderhuunde") sunt nai früünd mäd do Fläddermuuse, man jo hääbe (buute ju ägyptiske Oard Rousettus aegyptiacus) neen Echolot-Orientierenge. Dät rakt disse Dierte in Afrikoa, Suud-Asien, Australien, Wääst-Ozeanien un Zypern. Me kon do uk in n Zoo hoolde. Jo sunt ju eensichste Familie fon ju Unneroardenge Megachiroptera. In ju Fäksproake kwäd me deeruum, disse Unneroardenge is monotypisk.

Ang kalwang ay bumubuo sa subkurya ng Megachiroptera, at ang tanging pamilya nito na Pteropodidae ng order na Chiroptera (paniki). Ang mga ito ay tinatawag ding mga kalwang, o lalo na ang genera na Acerodon at Pteropus, na lumilipad na mga kalwang. Ang mga kalwang ay matatagpuan sa Amerika, Kanlurang Europa, hilagang-kanluran ng Aprika at timog-kanluran ng Australia.

La familha dels Pteropodidae amassa de ratapenadas generalament frugivòras. Aquesta familha foguèt creada per Gray en 1821.

Ӏимаьшкаш (эрс: Крыла́ны), Ӏимаьшка (эрс: Крыла́новые, лат: Pteropodidae) — дакхадийнатий дезал ба кулгаткъама (Chiroptera) тоабан Yinpterochiroptera яхача кIалтоаба юкъебоагIаш (хьалхагIа из дезал Megachiroptera яха къаьстта кIалтоаба санна белгалбоаккхар, амма хIанзарча молекулярно-генетическеи кариологическеи дараш бакъдец из).

Pteropodidae яхача дезало чулоац 170 совгIа кеп (40 ваьр).

КIалдезал Pteropodinae

КIалдезал Macroglossinae[2]

Подсемейство Cynopterinae

Подсемейство Eidolinae

Подсемейство Rousettinae (включая Epomophorinae)

Подсемейство Harpyionycterinae

Подсемейство Nyctimeninae

В конце 1980-х — начале 1990-х гг. было высказано предположение о том, что представители Megachiroptera и Microchiroptera выработали способность к машущему полету в результате конвергентной эволюции. Эта точка зрения, впрочем, не получила широкого распространения, позднейшие кариологические и молекулярно-генетические исследования также ни в коей мере ее не подтверждают.

Ӏимаьшкаш (эрс: Крыла́ны), Ӏимаьшка (эрс: Крыла́новые, лат: Pteropodidae) — дакхадийнатий дезал ба кулгаткъама (Chiroptera) тоабан Yinpterochiroptera яхача кIалтоаба юкъебоагIаш (хьалхагIа из дезал Megachiroptera яха къаьстта кIалтоаба санна белгалбоаккхар, амма хIанзарча молекулярно-генетическеи кариологическеи дараш бакъдец из).

Kaluang adalah angguta bangsa kalalawar (Chiroptera) nang tagulung dalam familia Pteropodidae, satu-satunya familia angguta subordo Megachiroptera. Kata "kaluang" rancak diguna'akan gasan manyambat kalalawar dalam pamandiran sahari-hari, walaupun sacara ilmiah hal ini kada sapanuhnya bujur, marga kada samunyaan kalalawar adalah kaluang. Kaluang adalah hérbivora, dan wastu mamakan buah-buahan atawa mahisap néktar matan kambang. Walaupun kaluang pada umumnya labih ganal daripada kalalawar, tagal kada samuanya samintu. Ada jua babarapa spésiés nang panjangnya wastu sakitar 6 séntimitir.

Kaluang baisi mata nang ganal sahingga walaupun kada salandap mata manusia, inya hingkat malihat kala sungsung atawa di dalam guha nang kadap. Indera nang sacara utama diguna'akan gasan navigasi adalah daya panciumannya nang landap. Inya kada mangandalakan diri pada daya pandangaran nangkaya halnya kalalawar, lawan kakacualian satu spésiés kaluang Mesir (Rousettus egyptiacus).

Walaupun kalalawar sacara umum kawa didapatakan di saluruh dunia, kaluang wastu didapatakan di dairah-dairah tropis di Asia, Aprika dan Oséania.

Suku Pteropodidae dibagi manjadi dua anak-suku (subfamilia) nang saluruhnya ba'angguta sakitar 188 spésiés, dalam 43 marga:

Suku PTEROPODIDAE

Kaluang adalah angguta bangsa kalalawar (Chiroptera) nang tagulung dalam familia Pteropodidae, satu-satunya familia angguta subordo Megachiroptera. Kata "kaluang" rancak diguna'akan gasan manyambat kalalawar dalam pamandiran sahari-hari, walaupun sacara ilmiah hal ini kada sapanuhnya bujur, marga kada samunyaan kalalawar adalah kaluang. Kaluang adalah hérbivora, dan wastu mamakan buah-buahan atawa mahisap néktar matan kambang. Walaupun kaluang pada umumnya labih ganal daripada kalalawar, tagal kada samuanya samintu. Ada jua babarapa spésiés nang panjangnya wastu sakitar 6 séntimitir.

Kaluang baisi mata nang ganal sahingga walaupun kada salandap mata manusia, inya hingkat malihat kala sungsung atawa di dalam guha nang kadap. Indera nang sacara utama diguna'akan gasan navigasi adalah daya panciumannya nang landap. Inya kada mangandalakan diri pada daya pandangaran nangkaya halnya kalalawar, lawan kakacualian satu spésiés kaluang Mesir (Rousettus egyptiacus).

Walaupun kalalawar sacara umum kawa didapatakan di saluruh dunia, kaluang wastu didapatakan di dairah-dairah tropis di Asia, Aprika dan Oséania.

Megabats constitute the family Pteropodidae of the order Chiroptera (bats). They are also called fruit bats, Old World fruit bats, or—especially the genera Acerodon and Pteropus—flying foxes. They are the only member of the superfamily Pteropodoidea, which is one of two superfamilies in the suborder Yinpterochiroptera. Internal divisions of Pteropodidae have varied since subfamilies were first proposed in 1917. From three subfamilies in the 1917 classification, six are now recognized, along with various tribes. As of 2018, 197 species of megabat had been described.

The leading theory of the evolution of megabats has been determined primarily by genetic data, as the fossil record for this family is the most fragmented of all bats. They likely evolved in Australasia, with the common ancestor of all living pteropodids existing approximately 31 million years ago. Many of their lineages probably originated in Melanesia, then dispersed over time to mainland Asia, the Mediterranean, and Africa. Today, they are found in tropical and subtropical areas of Eurasia, Africa, and Oceania.

The megabat family contains the largest bat species, with individuals of some species weighing up to 1.45 kg (3.2 lb) and having wingspans up to 1.7 m (5.6 ft). Not all megabats are large-bodied; nearly a third of all species weigh less than 50 g (1.8 oz). They can be differentiated from other bats due to their dog-like faces, clawed second digits, and reduced uropatagium. Only members of one genus, Notopteris, have tails. Megabats have several adaptations for flight, including rapid oxygen consumption, the ability to sustain heart rates of more than 700 beats per minute, and large lung volumes.

Most megabats are nocturnal or crepuscular, although a few species are active during the daytime. During the period of inactivity, they roost in trees or caves. Members of some species roost alone, while others form colonies of up to a million individuals. During the period of activity, they use flight to travel to food resources. With few exceptions, they are unable to echolocate, relying instead on keen senses of sight and smell to navigate and locate food. Most species are primarily frugivorous and several are nectarivorous. Other less common food resources include leaves, pollen, twigs, and bark.

They reach sexual maturity slowly and have a low reproductive output. Most species have one offspring at a time after a pregnancy of four to six months. This low reproductive output means that after a population loss their numbers are slow to rebound. A quarter of all species are listed as threatened, mainly due to habitat destruction and overhunting. Megabats are a popular food source in some areas, leading to population declines and extinction. They are also of interest to those involved in public health as they are natural reservoirs of several viruses that can affect humans.

Epomophorini

Internal relationships of African Pteropodidae based on combined evidence of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA. One species each of Pteropodinae, Nyctimeninae, and Cynopterinae, which are not found in Africa, were included as outgroups.[2]The family Pteropodidae was first described in 1821 by British zoologist John Edward Gray. He named the family "Pteropidae" (after the genus Pteropus) and placed it within the now-defunct order Fructivorae.[3] Fructivorae contained one other family, the now-defunct Cephalotidae, containing one genus, Cephalotes[3] (now recognized as a synonym of Dobsonia).[4] Gray's spelling was possibly based on a misunderstanding of the suffix of "Pteropus".[5] "Pteropus" comes from Ancient Greek "pterón" meaning "wing" and "poús" meaning "foot".[6] The Greek word pous of Pteropus is from the stem word pod-; therefore, Latinizing Pteropus correctly results in the prefix "Pteropod-".[7]: 230 French biologist Charles Lucien Bonaparte was the first to use the corrected spelling Pteropodidae in 1838.[7]: 230

In 1875, the zoologist George Edward Dobson was the first to split the order Chiroptera (bats) into two suborders: Megachiroptera (sometimes listed as Macrochiroptera) and Microchiroptera, which are commonly abbreviated to megabats and microbats.[8] Dobson selected these names to allude to the body size differences of the two groups, with many fruit-eating bats being larger than insect-eating bats. Pteropodidae was the only family he included within Megachiroptera.[5][8]

A 2001 study found that the dichotomy of megabats and microbats did not accurately reflect their evolutionary relationships. Instead of Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera, the study's authors proposed the new suborders Yinpterochiroptera and Yangochiroptera.[9] This classification scheme has been verified several times subsequently and remains widely supported as of 2019.[10][11][12][13] Since 2005, this suborder has alternatively been called "Pteropodiformes".[7]: 520–521 Yinpterochiroptera contained species formerly included in Megachiroptera (all of Pteropodidae), as well as several families formerly included in Microchiroptera: Megadermatidae, Rhinolophidae, Nycteridae, Craseonycteridae, and Rhinopomatidae.[9] Two superfamilies comprise Yinpterochiroptera: Rhinolophoidea—containing the above families formerly in Microchiroptera—and Pteropodoidea, which only contains Pteropodidae.[14]

In 1917, Danish mammalogist Knud Andersen divided Pteropodidae into three subfamilies: Macroglossinae, Pteropinae (corrected to Pteropodinae), and Harpyionycterinae.[15]: 496 A 1995 study found that Macroglossinae as previously defined, containing the genera Eonycteris, Notopteris, Macroglossus, Syconycteris, Melonycteris, and Megaloglossus, was paraphyletic, meaning that the subfamily did not group all the descendants of a common ancestor.[16]: 214 Subsequent publications consider Macroglossini as a tribe within Pteropodinae that contains only Macroglossus and Syconycteris.[17][18] Eonycteris and Melonycteris are within other tribes in Pteropodinae,[2][18] Megaloglossus was placed in the tribe Myonycterini of the subfamily Rousettinae, and Notopteris is of uncertain placement.[18]

Other subfamilies and tribes within Pteropodidae have also undergone changes since Andersen's 1917 publication.[18] In 1997, the pteropodids were classified into six subfamilies and nine tribes based on their morphology, or physical characteristics.[18] A 2011 genetic study concluded that some of these subfamilies were paraphyletic and therefore they did not accurately depict the relationships among megabat species. Three of the subfamilies proposed in 1997 based on morphology received support: Cynopterinae, Harpyionycterinae, and Nyctimeninae. The other three clades recovered in this study consisted of Macroglossini, Epomophorinae + Rousettini, and Pteropodini + Melonycteris.[18] A 2016 genetic study focused only on African pteropodids (Harpyionycterinae, Rousettinae, and Epomophorinae) also challenged the 1997 classification. All species formerly included in Epomophorinae were moved to Rousettinae, which was subdivided into additional tribes. The genus Eidolon, formerly in the tribe Rousettini of Rousettinae, was moved to its own subfamily, Eidolinae.[2]

In 1984, an additional pteropodid subfamily, Propottininae, was proposed, representing one extinct species described from a fossil discovered in Africa, Propotto leakeyi.[19] In 2018 the fossils were reexamined and determined to represent a lemur.[20] As of 2018, there were 197 described species of megabat,[21] around a third of which are flying foxes of the genus Pteropus.[22]

The fossil record for pteropodid bats is the most incomplete of any bat family. Although the poor skeletal record of Chiroptera is probably from how fragile bat skeletons are, Pteropodidae still have the most incomplete despite generally having the biggest and most sturdy skeletons. It is also surprising that Pteropodidae are the least represented because they were the first major group to diverge.[23] Several factors could explain why so few pteropodid fossils have been discovered: tropical regions where their fossils might be found are under-sampled relative to Europe and North America; conditions for fossilization are poor in the tropics, which could lead to fewer fossils overall; and even when fossils are formed, they may be destroyed by subsequent geological activity.[24] It is estimated that more than 98% of pteropodid fossil history is missing.[25] Even without fossils, the age and divergence times of the family can still be estimated by using computational phylogenetics. Pteropodidae split from the superfamily Rhinolophoidea (which contains all the other families of the suborder Yinpterochiroptera) approximately 58 Mya (million years ago).[25] The ancestor of the crown group of Pteropodidae, or all living species, lived approximately 31 Mya.[26]

The family Pteropodidae likely originated in Australasia based on biogeographic reconstructions.[2] Other biogeographic analyses have suggested that the Melanesian Islands, including New Guinea, are a plausible candidate for the origin of most megabat subfamilies, with the exception of Cynopterinae;[18] the cynopterines likely originated on the Sunda Shelf based on results of a Weighted Ancestral Area Analysis of six nuclear and mitochondrial genes.[26] From these regions, pteropodids colonized other areas, including continental Asia and Africa. Megabats reached Africa in at least four distinct events. The four proposed events are represented by (1) Scotonycteris, (2) Rousettus, (3) Scotonycterini, and (4) the "endemic Africa clade", which includes Stenonycterini, Plerotini, Myonycterini, and Epomophorini, according to a 2016 study. It is unknown when megabats reached Africa, but several tribes (Scotonycterini, Stenonycterini, Plerotini, Myonycterini, and Epomophorini) were present by the Late Miocene. How megabats reached Africa is also unknown. It has been proposed that they could have arrived via the Middle East before it became more arid at the end of the Miocene. Conversely, they could have reached the continent via the Gomphotherium land bridge, which connected Africa and the Arabian Peninsula to Eurasia. The genus Pteropus (flying foxes), which is not found on mainland Africa, is proposed to have dispersed from Melanesia via island hopping across the Indian Ocean;[27] this is less likely for other megabat genera, which have smaller body sizes and thus have more limited flight capabilities.[2]

Megabats are the only family of bats incapable of laryngeal echolocation. It is unclear whether the common ancestor of all bats was capable of echolocation, and thus echolocation was lost in the megabat lineage, or multiple bat lineages independently evolved the ability to echolocate (the superfamily Rhinolophoidea and the suborder Yangochiroptera). This unknown element of bat evolution has been called a "grand challenge in biology".[28] A 2017 study of bat ontogeny (embryonic development) found evidence that megabat embryos at first have large, developed cochlea similar to echolocating microbats, though at birth they have small cochlea similar to non-echolocating mammals. This evidence supports that laryngeal echolocation evolved once among bats, and was lost in pteropodids, rather than evolving twice independently.[29] Megabats in the genus Rousettus are capable of primitive echolocation through clicking their tongues.[30] Some species—the cave nectar bat (Eonycteris spelaea), lesser short-nosed fruit bat (Cynopterus brachyotis), and the long-tongued fruit bat (Macroglossus sobrinus)— have been shown to create clicks similar to those of echolocating bats using their wings.[31]

Both echolocation and flight are energetically expensive processes.[32] Echolocating bats couple sound production with the mechanisms engaged for flight, allowing them to reduce the additional energy burden of echolocation. Instead of pressurizing a bolus of air for the production of sound, laryngeally echolocating bats likely use the force of the downbeat of their wings to pressurize the air, cutting energetic costs by synchronizing wingbeats and echolocation.[33] The loss of echolocation (or conversely, the lack of its evolution) may be due to the uncoupling of flight and echolocation in megabats.[34] The larger average body size of megabats compared to echolocating bats[35] suggests a larger body size disrupts the flight-echolocation coupling and made echolocation too energetically expensive to be conserved in megabats.[34]

The family Pteropodidae is divided into six subfamilies represented by 46 genera:[2][18]

Family Pteropodidae

Megabats are so called for their larger weight and size; the largest, the great flying fox (Pteropus neohibernicus) weighs up to 1.6 kg (3.5 lb);[38] some members of Acerodon and Pteropus have wingspans reaching up to 1.7 m (5.6 ft).[39]: 48 Despite the fact that body size was a defining characteristic that Dobson used to separate microbats and megabats, not all species of megabat are larger than microbats; the spotted-winged fruit bat (Balionycteris maculata), a megabat, weighs only 14.2 g (0.50 oz).[35] The flying foxes of Pteropus and Acerodon are often taken as exemplars of the whole family in terms of body size. In reality, these genera are outliers, creating a misconception of the true size of most megabat species.[5] A 2004 review stated that 28% of megabat species weigh less than 50 g (1.8 oz).[35]

Megabats can be distinguished from microbats in appearance by their dog-like faces, by the presence of claws on the second digit (see Megabat#Postcrania), and by their simple ears.[40] The simple appearance of the ear is due in part to the lack of tragi (cartilage flaps projecting in front of the ear canal), which are found in many microbat species. Megabats of the genus Nyctimene appear less dog-like, with shorter faces and tubular nostrils.[41] A 2011 study of 167 megabat species found that while the majority (63%) have fur that is a uniform color, other patterns are seen in this family. These include countershading in four percent of species, a neck band or mantle in five percent of species, stripes in ten percent of species, and spots in nineteen percent of species.[42]

Unlike microbats, megabats have a greatly reduced uropatagium, which is an expanse of flight membrane that runs between the hind limbs.[43] Additionally, the tail is absent or greatly reduced,[41] with the exception of Notopteris species, which have a long tail.[44] Most megabat wings insert laterally (attach to the body directly at the sides). In Dobsonia species, the wings attach nearer the spine, giving them the common name of "bare-backed" or "naked-backed" fruit bats.[43]

Megabats have large orbits, which are bordered by well-developed postorbital processes posteriorly. The postorbital processes sometimes join to form the postorbital bar. The snout is simple in appearance and not highly modified, as is seen in other bat families.[45] The length of the snout varies among genera. The premaxilla is well-developed and usually free,[4] meaning that it is not fused with the maxilla; instead, it articulates with the maxilla via ligaments, making it freely movable.[46][47] The premaxilla always lack a palatal branch.[4] In species with a longer snout, the skull is usually arched. In genera with shorter faces (Penthetor, Nyctimene, Dobsonia, and Myonycteris), the skull has little to no bending.[48]

The number of teeth varies among megabat species; totals for various species range from 24 to 34. All megabats have two or four each of upper and lower incisors, with the exception Bulmer's fruit bat (Aproteles bulmerae), which completely lacks incisors,[49] and the São Tomé collared fruit bat (Myonycteris brachycephala), which has two upper and three lower incisors.[50] This makes it the only mammal species with an asymmetrical dental formula.[50]

All species have two upper and lower canine teeth. The number of premolars is variable, with four or six each of upper and lower premolars. The first upper and lower molars are always present, meaning that all megabats have at least four molars. The remaining molars may be present, present but reduced, or absent.[49] Megabat molars and premolars are simplified, with a reduction in the cusps and ridges resulting in a more flattened crown.[51]

Like most mammals, megabats are diphyodont, meaning that the young have a set of deciduous teeth (milk teeth) that falls out and is replaced by permanent teeth. For most species, there are 20 deciduous teeth. As is typical for mammals,[52] the deciduous set does not include molars.[51]

The scapulae (shoulder blades) of megabats have been described as the most primitive of any chiropteran family.[51] The shoulder is overall of simple construction, but has some specialized features. The primitive insertion of the omohyoid muscle from the clavicle (collarbone) to the scapula is laterally displaced (more towards the side of the body)—a feature also seen in the Phyllostomidae. The shoulder also has a well-developed system of muscular slips (narrow bands of muscle that augment larger muscles) that anchor the tendon of the occipitopollicalis muscle (muscle in bats that runs from base of neck to the base of the thumb)[43] to the skin.[41]

While microbats only have claws on the thumbs of their forelimbs, most megabats have a clawed second digit as well;[51] only Eonycteris, Dobsonia, Notopteris, and Neopteryx lack the second claw.[53] The first digit is the shortest, while the third digit is the longest. The second digit is incapable of flexion.[51] Megabats' thumbs are longer relative to their forelimbs than those of microbats.[43]

Megabats' hindlimbs have the same skeletal components as humans. Most megabat species have an additional structure called the calcar, a cartilage spur arising from the calcaneus.[54] Some authors alternately refer to this structure as the uropatagial spur to differentiate it from microbats' calcars, which are structured differently. The structure exists to stabilize the uropatagium, allowing bats to adjust the camber of the membrane during flight. Megabats lacking the calcar or spur include Notopteris, Syconycteris, and Harpyionycteris.[55] The entire leg is rotated at the hip compared to normal mammal orientation, meaning that the knees face posteriorly. All five digits of the foot flex in the direction of the sagittal plane, with no digit capable of flexing in the opposite direction, as in the feet of perching birds.[54]

Flight is very energetically expensive, requiring several adaptations to the cardiovascular system. During flight, bats can raise their oxygen consumption by twenty times or more for sustained periods; human athletes can achieve an increase of a factor of twenty for a few minutes at most.[56] A 1994 study of the straw-coloured fruit bat (Eidolon helvum) and hammer-headed bat (Hypsignathus monstrosus) found a mean respiratory exchange ratio (carbon dioxide produced:oxygen used) of approximately 0.78. Among these two species, the gray-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) and the Egyptian fruit bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus), maximum heart rates in flight varied between 476 beats per minute (gray-headed flying fox) and 728 beats per minute (Egyptian fruit bat). The maximum number of breaths per minute ranged from 163 (gray-headed flying fox) to 316 (straw-colored fruit bat).[57] Additionally, megabats have exceptionally large lung volumes relative to their sizes. While terrestrial mammals such as shrews have a lung volume of 0.03 cm3 per gram of body weight (0.05 in3 per ounce of body weight), species such as the Wahlberg's epauletted fruit bat (Epomophorus wahlbergi) have lung volumes 4.3 times greater at 0.13 cm3 per gram (0.22 in3 per ounce).[56]

Megabats have rapid digestive systems, with a gut transit time of half an hour or less.[41] The digestive system is structured to a herbivorous diet sometimes restricted to soft fruit or nectar.[58] The length of the digestive system is short for a herbivore (as well as shorter than those of insectivorous microchiropterans),[58] as the fibrous content is mostly separated by the action of the palate, tongue, and teeth, and then discarded.[58] Many megabats have U-shaped stomachs. There is no distinct difference between the small and large intestine, nor a distinct beginning of the rectum. They have very high densities of intestinal microvilli, which creates a large surface area for the absorption of nutrients.[59]

Like all bats, megabats have much smaller genomes than other mammals. A 2009 study of 43 megabat species found that their genomes ranged from 1.86 picograms (pg, 978 Mbp per pg) in the straw-colored fruit bat to 2.51 pg in Lyle's flying fox (Pteropus lylei). All values were much lower than the mammalian average of 3.5 pg. Megabats have even smaller genomes than microbats, with a mean weight of 2.20 pg compared to 2.58 pg. It was speculated that this difference could be related to the fact that the megabat lineage has experienced an extinction of the LINE1—a type of long interspersed nuclear element. LINE1 constitutes 15–20% of the human genome and is considered the most prevalent long interspersed nuclear element among mammals.[60]

With very few exceptions, megabats do not echolocate, and therefore rely on sight and smell to navigate.[61] They have large eyes positioned at the front of their heads.[62] These are larger than those of the common ancestor of all bats, with one study suggesting a trend of increasing eye size among pteropodids. A study that examined the eyes of 18 megabat species determined that the common blossom bat (Syconycteris australis) had the smallest eyes at a diameter of 5.03 mm (0.198 in), while the largest eyes were those of large flying fox (Pteropus vampyrus) at 12.34 mm (0.486 in) in diameter.[63] Megabat irises are usually brown, but they can be red or orange, as in Desmalopex, Mirimiri, Pteralopex, and some Pteropus.[64]

At high brightness levels, megabat visual acuity is poorer than that of humans; at low brightness it is superior.[62] One study that examined the eyes of some Rousettus, Epomophorus, Eidolon, and Pteropus species determined that the first three genera possess a tapetum lucidum, a reflective structure in the eyes that improves vision at low light levels, while the Pteropus species do not.[61] All species examined had retinae with both rod cells and cone cells, but only the Pteropus species had S-cones, which detect the shortest wavelengths of light; because the spectral tuning of the opsins was not discernible, it is unclear whether the S-cones of Pteropus species detect blue or ultraviolet light. Pteropus bats are dichromatic, possessing two kinds of cone cells. The other three genera, with their lack of S-cones, are monochromatic, unable to see color. All genera had very high densities of rod cells, resulting in high sensitivity to light, which corresponds with their nocturnal activity patterns. In Pteropus and Rousettus, measured rod cell densities were 350,000–800,000 per square millimeter, equal to or exceeding other nocturnal or crepuscular animals such as the house mouse, domestic cat, and domestic rabbit.[61]

Megabats use smell to find food sources like fruit and nectar.[65] They have keen senses of smell that rival that of the domestic dog.[66] Tube-nosed fruit bats such as the eastern tube-nosed bat (Nyctimene robinsoni) have stereo olfaction, meaning they are able to map and follow odor plumes three-dimensionally.[66] Along with most (or perhaps all) other bat species, megabats mothers and offspring also use scent to recognize each other, as well as for recognition of individuals.[65] In flying foxes, males have enlarged androgen-sensitive sebaceous glands on their shoulders they use for scent-marking their territories, particularly during the mating season. The secretions of these glands vary by species—of the 65 chemical compounds isolated from the glands of four species, no compound was found in all species.[67] Males also engage in urine washing, or coating themselves in their own urine.[67][68]

Megabats possess the TAS1R2 gene, meaning they have the ability to detect sweetness in foods. This gene is present among all bats except vampire bats. Like all other bats, megabats cannot taste umami, due to the absence of the TAS1R1 gene. Among other mammals, only giant pandas have been shown to lack this gene.[65] Megabats also have multiple TAS2R genes, indicating that they can taste bitterness.[69]

Megabats, like all bats, are long-lived relative to their size for mammals. Some captive megabats have had lifespans exceeding thirty years.[53] Relative to their sizes, megabats have low reproductive outputs and delayed sexual maturity, with females of most species not giving birth until the age of one or two.[70]: 6 Some megabats appear to be able to breed throughout the year, but the majority of species are likely seasonal breeders.[53] Mating occurs at the roost.[71] Gestation length is variable,[72] but is four to six months in most species. Different species of megabats have reproductive adaptations that lengthen the period between copulation and giving birth. Some species such as the straw-colored fruit bat have the reproductive adaptation of delayed implantation, meaning that copulation occurs in June or July, but the zygote does not implant into the uterine wall until months later in November.[70]: 6 The Fischer's pygmy fruit bat (Haplonycteris fischeri), with the adaptation of post-implantation delay, has the longest gestation length of any bat species, at up to 11.5 months.[72] The post-implantation delay means that development of the embryo is suspended for up to eight months after implantation in the uterine wall, which is responsible for its very long pregnancies.[70]: 6 Shorter gestation lengths are found in the greater short-nosed fruit bat (Cynopterus sphinx) with a period of three months.[73]

The litter size of all megabats is usually one.[70]: 6 There are scarce records of twins in the following species: Madagascan flying fox (Pteropus rufus), Dobson's epauletted fruit bat (Epomops dobsoni), the gray-headed flying fox, the black flying fox (Pteropus alecto), the spectacled flying fox (Pteropus conspicillatus),[74] the greater short-nosed fruit bat,[75] Peters's epauletted fruit bat (Epomophorus crypturus), the hammer-headed bat, the straw-colored fruit bat, the little collared fruit bat (Myonycteris torquata), the Egyptian fruit bat, and Leschenault's rousette (Rousettus leschenaultii).[76]: 85–87 In the cases of twins, it is rare that both offspring survive.[74] Because megabats, like all bats, have low reproductive rates, their populations are slow to recover from declines.[77]

At birth, megabat offspring are, on average, 17.5% of their mother's post-partum weight. This is the smallest offspring-to-mother ratio for any bat family; across all bats, newborns are 22.3% of their mother's post-partum weight. Megabat offspring are not easily categorized into the traditional categories of altricial (helpless at birth) or precocial (capable at birth). Species such as the greater short-nosed fruit bat are born with their eyes open (a sign of precocial offspring), whereas the Egyptian fruit bat offspring's eyes do not open until nine days after birth (a sign of altricial offspring).[78]

As with nearly all bat species, males do not assist females in parental care.[79] The young stay with their mothers until they are weaned; how long weaning takes varies throughout the family. Megabats, like all bats, have relatively long nursing periods: offspring will nurse until they are approximately 71% of adult body mass, compared to 40% of adult body mass in non-bat mammals.[80] Species in the genus Micropteropus wean their young by seven to eight weeks of age, whereas the Indian flying fox (Pteropus medius) does not wean its young until five months of age.[76] Very unusually, male individuals of two megabat species, the Bismarck masked flying fox (Pteropus capistratus) and the Dayak fruit bat (Dyacopterus spadiceus), have been observed producing milk, but there has never been an observation of a male nursing young.[81] It is unclear if the lactation is functional and males actually nurse pups or if it is a result of stress or malnutrition.[82]

Many megabat species are highly gregarious or social. Megabats will vocalize to communicate with each other, creating noises described as "trill-like bursts of sound",[83] honking,[84] or loud, bleat-like calls[85] in various genera. At least one species, the Egyptian fruit bat, is capable of a kind of vocal learning called vocal production learning, defined as "the ability to modify vocalizations in response to interactions with conspecifics".[86][87] Young Egyptian fruit bats are capable of acquiring a dialect by listening to their mothers, as well as other individuals in their colonies. It has been postulated that these dialect differences may result in individuals of different colonies communicating at different frequencies, for instance.[88][89]

Megabat social behavior includes using sexual behaviors for more than just reproduction. Evidence suggests that female Egyptian fruit bats take food from males in exchange for sex. Paternity tests confirmed that the males from which each female scrounged food had a greater likelihood of fathering the scrounging female's offspring.[90] Homosexual fellatio has been observed in at least one species, the Bonin flying fox (Pteropus pselaphon).[91][92] This same-sex fellatio is hypothesized to encourage colony formation of otherwise-antagonistic males in colder climates.[91][92]

Megabats are mostly nocturnal and crepuscular, though some have been observed flying during the day.[39] A few island species and subspecies are diurnal, hypothesized as a response to a lack of predators. Diurnal taxa include a subspecies of the black-eared flying fox (Pteropus melanotus natalis), the Mauritian flying fox (Pteropus niger), the Caroline flying fox (Pteropus molossinus), a subspecies of Pteropus pelagicus (P. p. insularis), and the Seychelles fruit bat (Pteropus seychellensis).[93]: 9

A 1992 summary of forty-one megabat genera noted that twenty-nine are tree-roosting genera. A further eleven genera roost in caves, and the remaining six genera roost in other kinds of sites (human structures, mines, and crevices, for example). Tree-roosting species can be solitary or highly colonial, forming aggregations of up to one million individuals. Cave-roosting species form aggregations ranging from ten individuals up to several thousand. Highly colonial species often exhibit roost fidelity, meaning that their trees or caves may be used as roosts for many years. Solitary species or those that aggregate in smaller numbers have less fidelity to their roosts.[70]: 2

Most megabats are primarily frugivorous.[94] Throughout the family, a diverse array of fruit is consumed from nearly 188 plant genera.[95] Some species are also nectarivorous, meaning that they also drink nectar from flowers.[94] In Australia, Eucalyptus flowers are an especially important food source.[41] Other food resources include leaves, shoots, buds, pollen, seed pods, sap, cones, bark, and twigs.[96] They are prodigious eaters and can consume up to 2.5 times their own body weight in fruit per night.[95]

Megabats fly to roosting and foraging resources. They typically fly straight and relatively fast for bats; some species are slower with greater maneuverability. Species can commute 20–50 km (12–31 mi) in a night. Migratory species of the genera Eidolon, Pteropus, Epomophorus, Rousettus, Myonycteris, and Nanonycteris can migrate distances up to 750 km (470 mi). Most megabats have below-average aspect ratios,[97] which is measurement relating wingspan and wing area.[97]: 348 Wing loading, which measures weight relative to wing area,[97]: 348 is average or higher than average in megabats.[97]

Megabats play an important role in seed dispersal. As a result of their long evolutionary history, some plants have evolved characteristics compatible with bat senses, including fruits that are strongly scented, brightly colored, and prominently exposed away from foliage. The bright colors and positioning of the fruit may reflect megabats' reliance on visual cues and inability to navigate through clutter. In a study that examined the fruits of more than forty fig species, only one fig species was consumed by both birds and megabats; most species are consumed by one or the other. Bird-consumed figs are frequently red or orange, while megabat-consumed figs are often yellow or green.[98] Most seeds are excreted shortly after consumption due to a rapid gut transit time, but some seeds can remain in the gut for more than twelve hours. This heightens megabats' capacity to disperse seeds far from parent trees.[99] As highly mobile frugivores, megabats have the capacity to restore forest between isolated forest fragments by dispersing tree seeds to deforested landscapes.[100] This dispersal ability is limited to plants with small seeds that are less than 4 mm (0.16 in) in length, as seeds larger than this are not ingested.[101]

Megabats, especially those living on islands, have few native predators: species like the small flying fox (Pteropus hypomelanus) have no known natural predators.[102] Non-native predators of flying foxes include domestic cats and rats. The mangrove monitor, which is a native predator for some megabat species but an introduced predator for others, opportunistically preys on megabats, as it is a capable tree climber.[103] Another species, the brown tree snake, can seriously impact megabat populations; as a non-native predator in Guam, the snake consumes so many offspring that it reduced the recruitment of the population of the Mariana fruit bat (Pteropus mariannus) to essentially zero. The island is now considered a sink for the Mariana fruit bat, as its population there relies on bats immigrating from the nearby island of Rota to bolster it rather than successful reproduction.[104] Predators that are naturally sympatric with megabats include reptiles such as crocodilians, snakes, and large lizards, as well as birds like falcons, hawks, and owls.[70]: 5 The saltwater crocodile is a known predator of megabats, based on analysis of crocodile stomach contents in northern Australia.[105] During extreme heat events, megabats like the little red flying fox (Pteropus scapulatus) must cool off and rehydrate by drinking from waterways, making them susceptible to opportunistic depredation by freshwater crocodiles.[106]

Megabats are the hosts of several parasite taxa. Known parasites include Nycteribiidae and Streblidae species ("bat flies"),[107][108] as well as mites of the genus Demodex.[109] Blood parasites of the family Haemoproteidae and intestinal nematodes of Toxocaridae also affect megabat species.[41][110]

Megabats are widely distributed in the tropics of the Old World, occurring throughout Africa, Asia, Australia, and throughout the islands of the Indian Ocean and Oceania.[18] As of 2013, fourteen genera of megabat are present in Africa, representing twenty-eight species. Of those twenty-eight species, twenty-four are only found in tropical or subtropical climates. The remaining four species are mostly found in the tropics, but their ranges also encompass temperate climates. In respect to habitat types, eight are exclusively or mostly found in forested habitat; nine are found in both forests and savannas; nine are found exclusively or mostly in savannas; and two are found on islands. Only one African species, the long-haired rousette (Rousettus lanosus), is found mostly in montane ecosystems, but an additional thirteen species' ranges extend into montane habitat.[111]: 226

Outside of Southeast Asia, megabats have relatively low species richness in Asia. The Egyptian fruit bat is the only megabat whose range is mostly in the Palearctic realm;[112] it and the straw-colored fruit bat are the only species found in the Middle East.[112][113] The northernmost extent of the Egyptian fruit bat's range is the northeastern Mediterranean.[112] In East Asia, megabats are found only in China and Japan. In China, only six species of megabat are considered resident, while another seven are present marginally (at the edge of their ranges), questionably (due to possible misidentification), or as accidental migrants.[114] Four megabat species, all Pteropus, are found on Japan, but none on its five main islands.[115][116][117][118] In South Asia, megabat species richness ranges from two species in the Maldives to thirteen species in India.[119] Megabat species richness in Southeast Asia is as few as five species in the small country of Singapore and seventy-six species in Indonesia.[119] Of the ninety-eight species of megabat found in Asia, forest is a habitat for ninety-five of them. Other habitat types include human-modified land (66 species), caves (23 species), savanna (7 species), shrubland (4 species), rocky areas (3 species), grassland (2 species), and desert (1 species).[119]

In Australia, five genera and eight species of megabat are present. These genera are Pteropus, Syconycteris, Dobsonia, Nyctimene, and Macroglossus.[41]: 3 Pteropus species of Australia are found in a variety of habitats, including mangrove-dominated forests, rainforests, and the wet sclerophyll forests of the Australian bush.[41]: 7 Australian Pteropus are often found in association with humans, as they situate their large colonies in urban areas, particularly in May and June when the greatest proportions of Pteropus species populations are found in these urban colonies.[120]