en

names in breadcrumbs

The American Black Duck eats seeds and vegetative parts of aquatic plants and crop plants. They also consume a rather high proportion of invertebrates (insects, molluscs, crustaceans) in spring and summer. They feed by grazing, probing, dabbling or upending in shallow water. They occasionally dive (Hoyo, et al 1992).

The Black Duck is an important waterfowl of North American hunters and has been for many years.

Not globally threatened.

The population of the Black Duck in the 1950's was around 2 million and since then has been on a steady decrease. Today the population has been calculated to be around 50,000. Causes of decline are unknown, but probably related to habitat loss, deterioration of water and food supplies, intense hunting pressure, and competition and hybridization with Mallards (Hoyo, et al 1992).

US Migratory Bird Act: protected

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

State of Michigan List: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Anas rubripes breeds from Manitoba southeast to Minnesota, east through Wisconsin, Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, and in the forested portions of eastern Canada to nortern Quebec and northern Labrador. The black duck winters in the southern parts of its breeding range and south to the Gulf Coast, Florida, and Bermuda (Mcauley, et al 1998).

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native )

The Black Duck during the breeding season prefers a variety of fresh and brackish waters in a forest environment. These include: alkaline marshes, acid bogs and muskegs, lakes, ponds, and stream margins, as well as tidewater habitats such as bays and estuaries. The most favored areas are brackish estuarine bays with extensive adjacent agricultural lands. Outside of the breeding season the duck lives on large, open lagoons and on the coast, even in rough sea waters (Merendino and Ankney, 1994).

The northernmost breeders descend to lower latitudes to winter on the Atlantic seaboard of North America, usually as far south as Texas. Some reports have been made of observation of Black Ducks in Korea, Puerto Rico, and Western Europe, where some have stayed for an extended period of time (Hoyo, et al 1992).

Habitat Regions: temperate ; freshwater

Aquatic Biomes: lakes and ponds; rivers and streams; coastal

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 317 months.

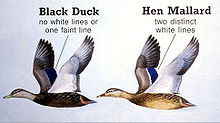

Males in breeding plumage have a buffy head that is heavily streaked with black, especially through the eye and on the tip of the head. The upperparts, including the tail and wing are blackish brown. The underparts feathers are dark sooty brown, with pale reddish and buff margins. The secondaries are iridescent blueish purple, with a black subterminal border and a narrow white tip, sometimes not present. The tertials are glossy black next to the speculum, but otherwise are gray to blackish brown, and the underwing surface is silvery white. The iris is brown, the bill is greenish yellow to bright yellow, with a black nail, and the feet and legs are orange red. Females also have a greenish to olive-colored bill, with small black spotting, and dusky to olive-colored legs and feet. Juveniles resemble adults, but are more heavily streaked on the breast and underparts, since these feathers have broader buff margins but darker tips. In the field the Black Duck has a body shaped like a Mallard. In flight, Black Ducks appear to be nearly black, with an underwing coloration that is in contrast with the rest of their plumage (Johngard, 1978).

Range mass: 1160 to 1330 g.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Average basal metabolic rate: 3.6076 W.

Breeding starts in March and April. Nearly all first-year females attempt to nest and older females usually return to their nesting areas of previous years and very frequently use an old nest site, or at least nest within 100 yards of an old nest site. The nest consists of a scrape on the ground, concealed among vegetation, sometimes in tree-cavities or crotches and lined with plant matter and down. Eggs are deposited in the nest at the approximate rate of one per day, and clutch sizes generally average between 9 and 10 eggs, with smaller clutches typical of first-year females. The time at which pair bonds are broken varies somewhat, with males typically remaining with their females about two weeks into the incubation period. Male participation in the brood rearing has not been reported. The incubation period is about 27 days. A fairly high rate of nest destruction is done by crows and racoons (Norman and Winston 1996). The first broods hatch in early May and peak hatch is in early June (Longcore, et al 1998). Young are mobile 1-3 hours after hatching. The female-brood pair bond lasts 6-7 weeks (Ehrlich, et al 1988).

Average eggs per season: 9.5.

Average time to hatching: 27 days.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; oviparous

Average time to hatching: 28 days.

Average eggs per season: 9.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

Sex: male: 365 days.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

Sex: female: 365 days.

At close range, the American Black Duck may be identified by its dark color, dull-yellow bill, and white under-wing patches. However, due to its large size (20-25 inches) and familiar oval-shaped body, the American Black Duck is often mistaken at a distance for the more ubiquitous Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos). Separating American Black Ducks from the Mallards has become increasingly difficult as Mallards have begun to interbreed with this species, producing hybrids with characteristics intermediate to those of the two parent species. Male and female pure-bred American Black Ducks are similar to one another in all seasons. The American Black Duck breeds across northeastern North America from the eastern edge of the Great Plains east to the Atlantic coast and from the Hudson Bay south to the Mid-Atlantic region. Northern populations migrate south in winter, when they may be found in the southeast and along the Ohio River Valley. Populations in the northeastern United States and in the Mid-Atlantic region migrate short distances (if at all), and this species may be found all year in these areas. American Black Ducks breed along lakes, streams, and in freshwater and saltwater marshes. Similar habitats are utilized by this species in winter. Most hybrids occur where appropriate habitats for American Black Ducks overlap with those of Mallards, especially in more built-up areas. Like the Mallard, this species is a generalist feeder, eating grasses and aquatic plants, seeds, grains, insects, mollusks, crustaceans, and fish. American Black Ducks are often found floating on the water’s surface, occasionally dabbling (submerging their head and chest while their legs and tail stick out of the water) to find food. These ducks are also capable of taking off directly from the water. They may also be found on land, where they may be observed walking, or in the air, where they may be observed making swift and direct flights between bodies of water. Small numbers of American Black Ducks may be looked for among larger flocks of Mallards. This species is most active during the day.

At close range, the American Black Duck may be identified by its dark color, dull-yellow bill, and white under-wing patches. However, due to its large size (20-25 inches) and familiar oval-shaped body, the American Black Duck is often mistaken at a distance for the more ubiquitous Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos). Separating American Black Ducks from the Mallards has become increasingly difficult as Mallards have begun to interbreed with this species, producing hybrids with characteristics intermediate to those of the two parent species. Male and female pure-bred American Black Ducks are similar to one another in all seasons. The American Black Duck breeds across northeastern North America from the eastern edge of the Great Plains east to the Atlantic coast and from the Hudson Bay south to the Mid-Atlantic region. Northern populations migrate south in winter, when they may be found in the southeast and along the Ohio River Valley. Populations in the northeastern United States and in the Mid-Atlantic region migrate short distances (if at all), and this species may be found all year in these areas. American Black Ducks breed along lakes, streams, and in freshwater and saltwater marshes. Similar habitats are utilized by this species in winter. Most hybrids occur where appropriate habitats for American Black Ducks overlap with those of Mallards, especially in more built-up areas. Like the Mallard, this species is a generalist feeder, eating grasses and aquatic plants, seeds, grains, insects, mollusks, crustaceans, and fish. American Black Ducks are often found floating on the water’s surface, occasionally dabbling (submerging their head and chest while their legs and tail stick out of the water) to find food. These ducks are also capable of taking off directly from the water. They may also be found on land, where they may be observed walking, or in the air, where they may be observed making swift and direct flights between bodies of water. Small numbers of American Black Ducks may be looked for among larger flocks of Mallards. This species is most active during the day.

The American black duck (Anas rubripes) is a large dabbling duck in the family Anatidae. It was described by William Brewster in 1902. It is the heaviest species in the genus Anas, weighing 720–1,640 g (1.59–3.62 lb) on average and measuring 54–59 cm (21–23 in) in length with an 88–95 cm (35–37 in) wingspan. It somewhat resembles the female and eclipse male mallard in coloration, but has a darker plumage. The male and female are generally similar in appearance, but the male's bill is yellow while the female's is dull green with dark marks on the upper mandible. It is native to eastern North America. During the breeding season, it is usually found in coastal and freshwater wetlands from Saskatchewan to the Atlantic in Canada and the Great Lakes and the Adirondacks in the United States. It is a partially migratory species, mostly wintering in the east-central United States, especially in coastal areas.

It interbreeds regularly and extensively with the mallard, to which it is closely related. The female lays six to fourteen oval eggs, which have smooth shells and come in varied shades of white and buff green. Hatching takes 30 days on average. Incubation usually takes 25 to 26 days, with both sexes sharing duties, although the male usually defends the territory until the female reaches the middle of her incubation period. It takes about six weeks to fledge. Once the eggs hatch, the hen leads the brood to rearing areas with abundant invertebrates and vegetation.

The American black duck is considered to be a species of least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), although some populations of the species are in decline. It has long been valued as a game bird. Habitat loss due to drainage, global warming, filling of wetlands due to urbanization and rising sea levels are major reasons for the declining population of the American black duck. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service has been purchasing and managing the habitat of this species in many areas to support the migratory stopover, wintering and breeding populations. The Atlantic Coast Joint Venture also protects habitat through restoration and land acquisition projects, mostly within their wintering and breeding areas.

American ornithologist William Brewster described the American black duck as Anas obscura rubripes, for "red-legged black duck",[2] in his landmark article "An undescribed form of the black duck (Anas obscura)," in The Auk in 1902, to distinguish between the two kinds of black ducks found in New England. One of them was described as being comparatively small, with brownish legs and an olivaceous or dusky bill, and the other as being comparatively larger, with a lighter skin tone, bright red legs and a clear yellow bill.[2] The larger of the two was described as Anas obscura by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin in 1789[1] in the 13th edition of the Systema Naturae, Part 2, and he based it on the "Dusky Duck" of Welsh naturalist Thomas Pennant.[2] The current scientific name, Anas rubripes, is derived from Latin, with Anas meaning "duck" and rubripes coming from ruber, "red", and pes, "foot".[3]

Pennant, in Arctic Zoology, Volume 2, described this duck as coming "from the province of New York" and having "a long and narrow dusky bill, tinged with blue: chin white: neck pale brown, streaked downwards with dusky lines."[2] In a typical obscura, characteristics such as greenish black, olive green or dusky olive bill; olivaceous brown legs with at most one reddish tinge; the nape and pileum nearly uniformly dark; spotless chin and throat; fine linear and dusky markings on the neck and sides of the head, rather than blackish, do not vary with age or season.[2]

The American black duck weighs 720–1,640 g (1.59–3.62 lb) and measures 54–59 cm (21–23 in) in length with a 88–95 cm (35–37 in) wingspan.[4] This species has the highest mean body mass in the genus Anas, with a sample of 376 males averaging 1.4 kg (3.1 lb) and 176 females averaging 1.1 kg (2.4 lb), although its size is typically quite similar to that of the familiar mallard.[5][6] The American black duck somewhat resembles the female mallard in coloration, although the black duck's plumage is darker.[7] Males and females are generally similar in appearance, but the male's bill is yellow while the female's is dull green with dark marks on the upper mandible,[8] which is occasionally flecked with black.[9][10] The head is brown, but is slightly lighter in tone than the darker brown body. The cheeks and throat are streaked brown, with a dark streak going through the crown and dark eye.[7] The speculum feathers are iridescent violet-blue with predominantly black margins.[8] The fleshy orange feet of the duck have dark webbing.[11]

Both male and female American black ducks produce similar calls to their close relative, the mallard, with the female producing a loud sequence of quacks which falls in pitch.[12]

In flight, the white lining of the underwings can be seen in contrast to the blackish underbody and upperside.[7][13] The purple speculum lacks white bands at the front and rear, and rarely has a white trailing edge. A dark crescent is visible on the median underwing primary coverts.[13]

Juveniles resemble adult females, but have broken narrow pale edges of underpart feathers, which give a slightly streaked rather than scalloped appearance, and the overall appearance is browner rather than uniformly blackish. Juvenile males have brownish-orange feet while juvenile females have brownish feet and a dusky greyish-green bill.[13]

The American black duck is endemic to eastern North America.[14] In Canada, the range extends from northeastern Saskatchewan to Newfoundland and Labrador.[7] In the United States, it is found in northern Illinois, Michigan, New Jersey, Ohio, Connecticut, Vermont, South Dakota, central West Virginia, Maine and on the Atlantic coast to North Carolina.[7][15]

The American black duck is a habitat generalist as it is associated with tidal marshes and present throughout the year in salt marshes from the Gulf of Maine to coastal Virginia.[16] It usually prefers freshwater and coastal wetlands throughout northeastern America, including brackish marshes, estuaries and edges of backwater ponds and rivers lined by speckled alder.[7][15] It also inhabits beaver ponds, shallow lakes with sedges and reeds, bogs in open boreal and mixed hardwood forests, as well as forested swamps.[15] Populations in Vermont have also been found in glacial kettle ponds surrounded by bog mats.[15] During winter, the American black duck mostly inhabits brackish marshes bordering bays, agricultural marshes, flooded timber, agricultural fields, estuaries and riverine areas.[15] Ducks usually take shelter from hunting and other disturbances by moving to brackish and fresh impoundments on conservation land.[4]

The American black duck is an omnivorous species[17] with a diverse diet.[18] It feeds by dabbling in shallow water and grazing on land.[17] Its plant diet primarily includes a wide variety of wetland grasses and sedges, and the seeds, stems, leaves and root stalks of aquatic plants, such as eelgrass, pondweed and smartweed.[7][8] Its animal diet includes mollusks, snails, amphipods, insects, mussels and small fishes.[17][18]

During the breeding season, the diet of the American black duck consists of approximately 80% plant food and 20% animal food. The animal food diet increases to 85% during winter.[17] During nesting, the proportion of invertebrates increases.[8] Ducklings mostly eat water invertebrates for the first 12 days after hatching, including aquatic snowbugs, snails, mayflies, dragonflies, beetles, flies, caddisflies and larvae. After this, they shift to seeds and other plant food.[17]

The breeding habitat includes alkaline marshes, acid bogs, lakes, ponds, rivers, marshes, brackish marshes and the margins of estuaries and other aquatic environments in northern Saskatchewan, Manitoba, across Ontario, Quebec and the Atlantic Canadian Provinces, plus the Great Lakes and the Adirondacks in the United States.[19] It is partially migratory, and many winter in the east-central United States, especially coastal areas; some remain year-round in the Great Lakes region.[20] This duck is a rare vagrant to Great Britain and Ireland, where over the years several birds have settled in and bred with the local mallard.[21] The resulting hybrid can present considerable identification difficulties.[21]

Nest sites are well-concealed on the ground, often in uplands. Egg clutches have six to fourteen oval eggs,[11] which have smooth shells and come in varied shades of white and buff green.[19] On average, they measure 59.4 mm (2.34 in) long, 43.2 mm (1.70 in) wide and weigh 56.6 g (0.125 lb).[19] Hatching takes 30 days on average.[11] The incubation period varies,[19] but usually takes 25 to 26 days.[22] Both sexes share duties, although the male usually defends the territory until the female reaches the middle of her incubation period.[22] It takes about six weeks to fledge.[22] Once the eggs hatch, the hen leads the brood to rearing areas with abundant invertebrates and vegetation.[22]

The American black duck interbreeds regularly and extensively with the mallard, to which it is closely related.[23] Some authorities even consider the black duck to be a subspecies of the mallard instead of a separate species. Mank et al. argue that this is in error as the extent of hybridization alone is not a valid means to delimitate Anas species.[24]

It has been proposed that the American black duck and the mallard were formerly separated by habitat preference, with the American black duck's dark plumage giving it a selective advantage in shaded forest pools in eastern North America, and the mallard's lighter plumage giving it an advantage in the brighter, more open prairie and plains lakes.[25] According to this view, recent deforestation in the east and tree planting on the plains has broken down this habitat separation, leading to the high levels of hybridization now observed.[26] However, rates of past hybridization are unknown in this and most other avian hybrid zones, and it is merely presumed in the case of the American black duck that past hybridization rates were lower than those seen today. Also, many avian hybrid zones are known to be stable and longstanding despite the occurrence of extensive interbreeding.[23] The American black duck and the local mallard are now very hard to distinguish by means of microsatellite comparisons, even if many specimens are sampled.[27] Contrary to this study's claims, the question of whether the American haplotype is an original mallard lineage is far from resolved. Their statement, "Northern black ducks are now no more distinct from mallards than their southern conspecifics" only holds true in regard to the molecular markers tested.[24] As birds indistinguishable according to the set of microsatellite markers still can look different, there are other genetic differences that were simply not tested in the study.[24]

In captivity studies, it has been discovered that the hybrids follow Haldane's Rule, with hybrid females often dying before they reach sexual maturity, thereby supporting the case for the American black duck being a distinct species.[23][28]

The apex nest predators of the American black duck include American crows, gulls and raccoons, especially in tree nests.[17] Hawks and owls are also major predators of adults. Bullfrogs and snapping turtles eat many ducklings.[17] Ducklings often catch diseases caused by protozoan blood parasites transmitted by bites of insects such as blackflies.[17] They are also vulnerable to lead shot poisoning, known as plumbism, due to their bottom-foraging food habits.[17]

Since 1988, the American black duck has been rated as least concern on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species.[1] This is because the range of this species is extremely large, which is not near the threshold of vulnerable species.[1] In addition, the total population is large, and, although it is declining, it is not declining fast enough to make the species vulnerable.[1] It has long been valued as a game bird, being extremely wary and fast flying.[29] Habitat loss due to drainage, filling of wetlands due to urbanization, global warming and rising sea levels are major reasons for the declining population.[14] Some conservationists consider hybridization and competition with the mallard as an additional source of concern should this decline continue.[30][31] Hybridization itself is not a major problem; natural selection makes sure that the best-adapted individuals have the most offspring.[32] However, the reduced viability of female hybrids causes some broods to fail in the long run due to the death of the offspring before reproducing themselves.[33] While this is not a problem in the plentiful mallard, it might place an additional strain on the American black duck's population. Recent research conducted for the Delta Waterfowl Foundation suggests that hybrids are a result of forced copulations and not a normal pairing choice by black hens.[34]

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service has continued to purchase and manage habitat in many areas to support the migratory stopover, wintering and breeding populations of the American black duck.[14] In addition, the Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge has purchased and restored over 1,000 acres of wetlands to provide stopover habitat for over 10,000 American black ducks during fall migration.[14] Also, the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture has been protecting the habitat of the American black duck through habitat restoration and land acquisition projects, mostly within their wintering and breeding areas.[14] In 2003, a Boreal Forest Conservation Framework was adopted by conservation organizations, industries and First Nations to protect the Canadian boreal forests, including the American black duck's eastern Canadian breeding range.[14]

The American black duck (Anas rubripes) is a large dabbling duck in the family Anatidae. It was described by William Brewster in 1902. It is the heaviest species in the genus Anas, weighing 720–1,640 g (1.59–3.62 lb) on average and measuring 54–59 cm (21–23 in) in length with an 88–95 cm (35–37 in) wingspan. It somewhat resembles the female and eclipse male mallard in coloration, but has a darker plumage. The male and female are generally similar in appearance, but the male's bill is yellow while the female's is dull green with dark marks on the upper mandible. It is native to eastern North America. During the breeding season, it is usually found in coastal and freshwater wetlands from Saskatchewan to the Atlantic in Canada and the Great Lakes and the Adirondacks in the United States. It is a partially migratory species, mostly wintering in the east-central United States, especially in coastal areas.

It interbreeds regularly and extensively with the mallard, to which it is closely related. The female lays six to fourteen oval eggs, which have smooth shells and come in varied shades of white and buff green. Hatching takes 30 days on average. Incubation usually takes 25 to 26 days, with both sexes sharing duties, although the male usually defends the territory until the female reaches the middle of her incubation period. It takes about six weeks to fledge. Once the eggs hatch, the hen leads the brood to rearing areas with abundant invertebrates and vegetation.

The American black duck is considered to be a species of least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), although some populations of the species are in decline. It has long been valued as a game bird. Habitat loss due to drainage, global warming, filling of wetlands due to urbanization and rising sea levels are major reasons for the declining population of the American black duck. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service has been purchasing and managing the habitat of this species in many areas to support the migratory stopover, wintering and breeding populations. The Atlantic Coast Joint Venture also protects habitat through restoration and land acquisition projects, mostly within their wintering and breeding areas.