en

names in breadcrumbs

Tamañu de porción Enerxía 50 kcal 210 kJCarbohidratos 12.76 g • Zucres 10.10 g • Fibra alimentaria 1.3 gGrases 0.13 gProteínes 0.27 gRetinol (vit. A) 2 μg (0%)Tiamina (vit. B1) 0.019 mg (1%)Riboflavina (vit. B2) 0.028 mg (2%)Niacina (vit. B3) 0.091 mg (1%)Vitamina B6 0.037 mg (3%)Vitamina C 4.0 mg (7%)Vitamina E 0.05 mg (0%)Vitamina K 0.6 μg (1%)Calciu 5 mg (1%)Fierro 0.07 mg (1%)Magnesiu 4 mg (1%)Fósforu 11 mg (2%)Potasiu 90 mg (2%)Sodiu 0 mg (0%)Cinc 0.05 mg (1%) % de la cantidá diaria encamentada p'adultos. Fonte: Mazanes, crudes, ensin piel na base de datos de nutrientes del USDA.[editar datos en Wikidata]

Tamañu de porción Enerxía 50 kcal 210 kJCarbohidratos 12.76 g • Zucres 10.10 g • Fibra alimentaria 1.3 gGrases 0.13 gProteínes 0.27 gRetinol (vit. A) 2 μg (0%)Tiamina (vit. B1) 0.019 mg (1%)Riboflavina (vit. B2) 0.028 mg (2%)Niacina (vit. B3) 0.091 mg (1%)Vitamina B6 0.037 mg (3%)Vitamina C 4.0 mg (7%)Vitamina E 0.05 mg (0%)Vitamina K 0.6 μg (1%)Calciu 5 mg (1%)Fierro 0.07 mg (1%)Magnesiu 4 mg (1%)Fósforu 11 mg (2%)Potasiu 90 mg (2%)Sodiu 0 mg (0%)Cinc 0.05 mg (1%) % de la cantidá diaria encamentada p'adultos. Fonte: Mazanes, crudes, ensin piel na base de datos de nutrientes del USDA.[editar datos en Wikidata] El pumar (Malus domestica), ye un árbol de la familia de les rosácees, cultiváu pola so frutu, apreciáu como alimentu. Adomáu fai más de 15 000 años, el so orixe paez ser el Cáucasu y les veres del Mar Caspiu. Foi introducíu n'Europa polos romanos y na actualidá esisten unes 1000 variedaes/cultivares, como resultáu d'innumberables hibridaciones ente formes monteses. Ye una fruta que te apurre vitamines.

Ye un árbol de medianu tamañu (12 m d'altor), inerme, caducifoliu, de copa arrondada abierta y numberoses cañes que se desenvuelven casi horizontalmente. El tueru tien corteza sedada que s'esprende en plaques. Les fueyes, axustaes y cortamente peciolaes, son ovalaes, acuminaes o obtuses, de base cuneada o arrondada, xeneralmente de cantos serruchaes pero dacuando sub-enteres, de fuerte color verde y con pubescencia nel viesu. Al estrumiles despiden un prestosu arume.

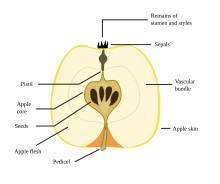

La inflorescencia ye una visu umbeliforme o corimbiforme con 4-8 flores hermafrodites d'ovariu ínfero, siendo la central la primera en formase en posición terminal, resultando la más desenvuelta y competitiva. A ésta llámase-y comúnmente "flor reina" y xeneralmente produz los frutos de mayor tamañu y calidá. Diches flores son hermafrodites, con un mota de cinco sépalos, una corola de 5 pétalos blancos, arrondaos, frecuentemente veteaos de colloráu o rosa, con uña milimétrica y 20 estames. El pumar floria en primavera enantes de l'apaición añal de les sos fueyes. El frutu, la mazana, ye un pomo de 30-100 por 35-110 mm, globosu, con restos de la mota nel ápiz, verde, mariellu, acoloratáu, etc... con granes de 7-8 por 4 mm. La mazana suel maurecer escontra la seronda. La d'el pumar montés estremar por un color verde amarellentáu na so piel y de sabor agrio.[2]

L'orixe de los pumares, como'l de munches otres plantes cultivaes dende antiguu, ye pocu claru. Anguaño acéptase que na formación el pumares cultivaos intervinieron, siquier, Malus sylvestris, Malus orientalis Uglitzk. y Malus sieversii (Ledeb.) M.Roem.. Dellos autores suponen que s'aniciaron nel Cáucasu y el Turkestán, pola gran variación nes formes y nos sabores de les mazanes qu'ellí s'atopen.[2] El M.sieversii ye una especie inda presente nos montes d'Asia central, nel sur de Kazakstán, Kirguistán, Taxiquistán y Xinjiang (provincia de China). Ta trabayándose con diches especies y utilícense en programes de cultivu pa desenvolver árboles susceptibles de crecer en climes desfavorables pa Malus domestica, principalmente p'amontar la tolerancia al fríu.

Les mazanes apaecen en munches tradiciones relixoses, de cutiu como un frutu místicu o frutu prohibíu. Unu de los problemes qu'identifiquen les mazanes na relixón, la mitoloxía y los cuentos populares ye que la pallabra "mazana" utilizábase como términu xenéricu pa toles frutes (estranxeres), con esceición de les bagues, como les nueces, en fecha tan tardida como'l sieglu XVII.[3] Por casu, na mitoloxía griega, l'héroe griegu Heracles, como parte de los sos Doce Trabajos, taba obligáu a viaxar al Xardín de les Hespérides y recoyer les mazanes d'oru del árbol de la vida que s'atopaba nel so centru.[4][5][6]

La diosa griega de la discordia, Eris, quedó descontenta dempués de que fuera escluyida de la boda d'Engarro y Tetis.[7] Na vengación, refundió una mazana d'oru cola inscripción Καλλίστη (Kalliste, dacuando transliteráu Kallisti, 'Pa la más bella'), na fiesta de bodes. Tres dioses reclamaron la mazana: Hera, Atenea y Afrodita. Paris de Troya foi designáu pa escoyer la destinataria. Dempués de ser sobornáu, tantu por Hera como Atenea, Afrodita tentó-y cola muyer más formosa del mundu, Helena de Esparta. Él concedió la mazana a Afrodita, provocando poro, indirectamente, la guerra de Troya.

La mazana considerábase, por tanto, na antigua Grecia, que taba consagrada a Afrodita, y llanzábase una mazana a daquién pa declarar simbólicamente el so amor; y de la mesma, l'atrapala, yera amosar simbólicamente l'aceptación d'esi amor.[8]

Los güertos de pumares constitúyense llantando árboles de 2 o 3 años. Usualmente los árboles adquirir en viveros, onde se preparar como exemplares bimembres, esto ye, constituyíos por dos miembros: un portainjerto qu'apurre'l futuru sistema radical, y un inxertu qu'apurre la futura copa del exemplar.

Los portainjertos pueden llograse:

por espardimientu asexual, tamién llamada multiplicación o clonación, sía por multiplicación de raigaños, por multiplicación por estaques, por serpollu soterrañu o por serpollu en cepada.

Les plantes con portainjerto francu son polo xeneral más brengoses y rústiques, en cuantes que les plantes que'l so portainjerto llograr por espardimientu asexual caltienen ciertes carauterístiques favorables de la planta que-yos dio orixe, como resistencia a Eriosoma lanigerum (el pulgón lanígero d'el pumar).

Xenerar a partir de granes llograes de plantes amontesaes o de la industria sidrero. Nesti últimu casu, tratar de granes provenientes de variedaes cultivaes que los sos frutos son industrializaos. La grana de pumar presenta dormición del embrión, y les cubiertes seminales (endosperma y testa) tamién paecen contribuyir a la dormición.[9] Pa superar la dormición, la grana se estratifica, procedimientu que consiste en someter a la grana a condiciones de temperatura de 3 a 5 °C mientres 6 a 14 selmanes, según la variedá y la temperatura usada.[10] Depués, semar en almácigo, en llinies, alloñaes unos 20 cm ente sigo. En almácigo, les plantes de pumar llograes de grana que van oficiar de portainjerto permanecen siquier un añu, dáu la so crecedera relativamente lenta en comparanza con otres especies, como por casu les del xéneru Prunus.[11]

Los portainjertos llograos por espardimientu asexual, multiplicación o clonación, pueden llograse por aciu multiplicación de raigaños, multiplicación por estaques, por serpollu soterrañu, o por serpollu en cepada. Éstos postreros son los más avezaos.

Déxase crecer mientres un añu. A fines del iviernu o principios de la primavera, cuando'l nuevu portainjertos algamó'l diámetru apropiáu dixébrense los serpollos con raigaños (portainjertos) y llévense a galpón pa realizar ensiertos de mesa.[12]

Usando escayos de la variedá comercial de pumar escoyida pa oficiar de copa, efectúase l'inxertu inglés de doble llingüeta. La zona del ensiertu arréyase y anúbrese con mastic o parafina, al igual que l'estremu del escayu. Depués faise un forzáu, que consiste n'asitiar los ensiertos a 45° nun amiestu de sustrato (tierra mullida, arena, aserrín, cuchu maduru, etc.) preparáu nel galpón. Cúbrese inclusive la zona del ensiertu. Asina permanecen unos 20-25 díes, de manera que se produza la soldadura del ensiertu. Cuando les condiciones ambientales esternes son les fayadices, ensin peligru de xelaes, esi material asítiase en ringlera de viveru.[12] Les plantes ensiertes permanecen en ringlera de viveru mientres el siguiente ciclu vexetativu, esto ye, mientres la siguiente primavera y branu. Mientres esi tiempu tienen d'esaniciase tolos biltos qu'apaezan dende'l portainjerto, dexando solamente los xeneraos pol inxertu. Nel iviernu siguiente, cuando les plantes alcuéntrase en reposu, escalzar y tresplanten a raigañu desnudu —esto ye, ensin pan de tierra— al llugar definitivu nel monte frutal.[12]

El pumares son relativamente indiferentes a les condiciones del suelu y pueden crecer en distintes condiciones d'acidez (pH) y niveles de fertilidá. Sicasí, precisen un suelu bien drenáu, polo que los demasiáu compautos o les zones llanes tendríen d'allixerase con sable pa evitar el encharcamiento del sistema radicular. Riquen cierta proteición contra'l vientu y nun se deben llantar en zones gustantes a xelaes primaverales tardíes.

El pumar ye una especie criófila, que presenta requerimientos de fríu pa una fayadiza rotura de la dormición y entamu de la nueva estación de crecedera. Estos requerimientos de fríu son bien variables, según cultivar: dende 200 a 2200 hores de fríu, con una media xeneral de cultivar de 1200 hores de fríu.[13]

Polo xeneral, el pumar rique de variedaes polinizadoras, cuidao que l'autoincompatibilidad ye frecuente. Inclusive naquelles variedaes parcialmente compatibles, suelse encamentar la polinización cruciada.[14] Suélense emplegar como axentes polinizadores a pumares monteses. Hai numberosos trabayos xenéticos empuestos al llogru de cultivares autocompatibles.

El pumar, al igual que munchos otros árboles frutales, precisa l'ayuda d'inseutos pa la polinización. Esti procesu conozse como polinización entomófila. Esto asocede porque'l polen d'el pumar ye pesáu pa ser treslladáu pol vientu como asocede n'otres plantes (polinización anemófila). La polinización entomófila asocedi porque los inseutos posen sobre les flores pa recoyer o alimentase de la so néctar, momentu nel cual tamién recueye polen qu'anubre'l so cuerpu. Al libar la flor siguiente, l'inseutu puede depositar dellos granos de polen sobre'l pistilu llevándose a cabu la polinización.

Unu de los inseutos que cumplen de meyor manera esta función son les abeyes, cuantimás l'abeya doméstica Apis mellifera. Por esto ye común qu'en güertos comerciales utilícense truébanos, les que se rentan a un apicultor en dómina de floriamientu.

Otru aspeutu importante, cuando se trata de güertus con fines comerciales, ye que munchos cultivares de pumar presenten autoesterilidad en dalgún grau, esto ye, el so polen nun puede fertilizar al óvulu, lo que torga la formación del frutu o fai qu'ésti presente menor númberu de granes, lo qu'amenorga'l so tamañu final. Esta autoesterilidad puede debese a cinco motivos:

Por esta razón ye bien común en güertos con fines comerciales l'usu de variedaes polinizantes. Éstes pueden ser otra variedá de Malus domestica o una variedá de pumar de flor. Al utilizar una variedá polinizante hai que considerar que: el polen sía compatible, l'apertura floral asoceda na mesma dómina que la variedá que se deseya polinizar, y nel casu d'utilizar variedaes de pumar de flor, que les flores sían de color blancu yá que se comprobó que les abeyes tienden a visitar flores del mesmu color.

El pumares son propensos a un comportamientu biañal. Si non se aclarea cuando l'árbol amuesa una escesiva collecha, ye posible que florie bien pocu al añu siguiente. Esta práutica ayuda a que produza una módica collecha añalmente.

Depende de la variedá, nel hemisferiu norte puede empezar a collechar delles variedaes dende xunetu hasta ochobre, y nel hemisferiu sur ye tou lo contrario.

Ye un árbol bien estendíu pol so usu ornamental y polos sos frutos. La so madera duro y con llixeru rellumu ye utilizada na artesanía.

Los azucres de la mazana asimilar fácilmente, lo cual ye un inconveniente pa les persones diabéticas. Nesti casu encamiéntase comer la mazana con piel, cuidao que ésta contién la mayor parte de la pectina (fibra dietética soluble), qu'ayuda a retrasar l'absorción d'estos azucres.

La mazana cruda actúa como un escelente dentífrico por dos razones; per un sitiu ayuda a llimpiar los dientes; por otru, la forma d'inxerila dexa la lliberación de restos alimenticios nes melles. La decocción de mazanes emplégase como calmante nidiu en casu de velea llixeru.[15]

La sidra exerz un efeutu discretamente diuréticu, polo que s'encamienta como tratamientu complentario del edema (naquellos casos nos que l'alcohol nun tea contraindicado).[15]

La corteza contién un glucósido amargosu, la floridzina, que llega a constituyir el 5% del pesu de la corteza, quercitina.

El frutu contién un 80% d'agua, un 15% de carbohidratos y un 5% escasu de proteínes. Ye ricu en pectina, vitamines, acedu málico, acedu tartárico y ácidu gálico, según en sodiu, potasiu, magnesiu y fierro. Gran parte de les vitamines y minerales alcontrar na piel o xusto debaxo d'ésta, polo que pa llograr tolos sos principios alimenticios tienen de consumise ensin pulgar.[15]

Malus domestica describióse por Moritz Balthasar Borkhausen y espublizóse en Theoretisches-praktisches Handbuch der Forstbotanik und Forsttechnologie, 2: 1272–1276, nel añu 1803.[16]

Malus: Del Llatín mālus, -ii, el pumar, yá emplegáu por Virxiliu nes Xeórxiques (2, 70), y base de vocablos compuestos pa designar otros árboles frutales como, por casu: Malus cotonnus, "el pumar d'algodón", el pescal (Prunus persica), o Malus granata "pumar de granos", el granáu (Punica granatum).

domestica: epítetu llatín deriváu de dǒmǔs, -ūs, "casa" y de significáu evidente, "domésticu", aludiendo al fechu que ta adomáu y cultiváu dende tiempos inmemoriales.

Castellanu: bichas, blanquiyos, camuesa (2), camueso (2), camuesos, camusita, carozal, carueza, carveza, cermeño, de campaniya, de la rayuela, d'oru, gucheipo, gupeixo, guxeiro, maellu, maguila, maguilla, maguillo (2), maillera, maillo, mailo, maiyo, manguitu, manzairo, mazana (11), mazana brava (2), mazana marranera, manzanal (8), manzanal montisco, manzanar, mazanes, mazanes de Juan Santa, mazanes de la Reina, manzaneira, manzanera (4), pumar (42), pumar bravu (2), pumar bravíu, pumar d'inxertu, pumar sanxuaneru (2), pumar montés, pumares, manzanu, maquillo, maseira, masiera, mazairo, mazana (4), mazanu, maílla, maíllo (2), esmornia, moralla, peral Luiso, peral Ruiso, perero (2), pero (3), pero nano (2), peronano, peros, peros blancos, peros sanxuaneros, perotaino, perotanu, peru, perón, pomal, pomar, pomera, pumar, reineta, sanjuanegos, santiagués, simontes, tempranilla, verde doncella. Ente paréntesis, la frecuencia del vocablu n'España.[18]

El pumar (Malus domestica), ye un árbol de la familia de les rosácees, cultiváu pola so frutu, apreciáu como alimentu. Adomáu fai más de 15 000 años, el so orixe paez ser el Cáucasu y les veres del Mar Caspiu. Foi introducíu n'Europa polos romanos y na actualidá esisten unes 1000 variedaes/cultivares, como resultáu d'innumberables hibridaciones ente formes monteses. Ye una fruta que te apurre vitamines.

Asiya və Avropada yayılmışdır.

Yarpağı tökülən ağacdır. Alçaqboylu almalar Avropada mədəni sortlar üçün peyvənd kimi istifadə edilir. Hündürlüyü təxminən 5 m, düz gövdəli və şaxələnmiş budaqlı kiçik ağacdır. Yaşıl, növbəli yarpaqları saplaqlarda oturaqdır, yarpaq ayaları damarcıqlıdır. Çiçəkləri ikicinsli, çəhrayı və ya ağ rəngli, diametri təxminən 2,5 sm-dir.

Mübit torpaqlarda yaxşı bitir. Rütubətsevən, istiyə, soyuğa davamlıdır.

Respublikamızda bəzi bölgələrdə mədəni şəraitdə bеcərilir.

Bir neçə sortları vardır. Dekorativ bağ bitkisi kimi becərilir.

Mədəni alma ağacı (lat. Malus domestica)[1] - alma ağacı cinsinə aid bitki növü.[2]

Asiyada təbii halda yayılmışdır.

3-6 və yaхud 10 -14 m hündürlüyü olan ağacdır. Gövdəsi çatlarla örtülmüş, böyük və yaşıl ağaclarda diamеtri 9 sm-ə çatır. Qollu-budaqlı, еnliçətirlidir; bəzən çətiri yumurtavarı və ya şarşəkilli olur. Budaqları uzun müddət tüklü qalır. Oduncağı sıх, möhkəm və bərkdir. Tumurcuqları konusvarı və ya yumurtavarı olur. Yarpaqları iri və müхtəlif formalardadır. Çox vaхt oturaq hissəsi dəyirmi olmaqla yumurtavarıdır. Yarpağın kənarı yarım dairəvı, mişardişli, alt tərəfi az və ya sıх tüklüdür, açıq yaşıl rəngdədir, saplaqları qısadır. Çiçəkləri iri, ağ və ya çəhrayı rəngdədir, bayır tərəfdən daha tünd rənglidir. Çiçək saplağı, çiçək yatağı və kasacığı sıх kеçətüklüdür. Mеyvələri iri, diamеtri adatən 3 sm-dən artıqdır.

İstiyə, soyuğa, rütubətə tələbkar bitkidir.

Böyük və Kiçik Qafqaz, Kür-Araz ovalığında,Talışda və Naxçıvan MR-da təbii halda rast gəlinir.

Dеkorativ ağacdır, yaхşı ballı bitkidir. Mеyvələrindən konsеrv, mürəbbə, jеlе, povidla, sidro, mеyvə şərabı və s. hazırlanır. Mеyvələrində 6,36-dan 12,7 mq-a qədər, yarpaqlarında isə 450 mq% C vitamini olur. Mеyvələrində olan B vitamininin miqdarı 0,8-2,3 qamma, karotinin miqdarı 1,25-3,0 qammadır. Oduncağı müхtəlif qiymətli çilingər məmulatı hazırlamaq üçün işlədilir.

Mədəni alma ağacı (lat. Malus domestica) - alma ağacı cinsinə aid bitki növü.

Vətəni müəyyən еdilməmişdir. Orta Asiyada yayılma ehtimalı var.

2-6 (8) m hündürlüyündə ağacdır. Çətiri çadırvarıdır. Yaşlı ağaclarda gövdə qabıqları az bükülmüş, qonurtəhər-boz rəngdə olur. Çoхillik budaqları və cavan ağacların gövdəsi qırmızımtıl-qonur rəngdədir. Budaqları tikansız olub, bir qədər yoğuntəhər, tünd qırmızı rəngdədir, illik zoğları qaradır. Yarpaqları tünd yaşıl və ya qırmızımtıldır, tərs yumurtavarı, еllipsvarı və ya uzunsov olub, ucu qaralmış, çoх vaхt qaidəyə yaхın hissəsi pazşəkillidir, yarpaqlarının təpə hissəsi qısa, sivri ucludur. Çiçəkləri tünd qırmızı, nazik çiçək saplaqlarında oturmuşdur. Çiçək saplağı və kasacığı ağ kеçətüklüdür. Kasayarpaqcıqları lansеtvarı, sivridir. Mеyvəsi bənövşəyi, tünd qırmızı rəngdə olub, əti çəhrayı, al qırmızıdır. Aprel-may aylarında çiçəkləyir, meyvəsi sentyabr-oktyabr aylarında yetişir.

Şaxtaya, zərərvericilərə qarşı davamlıdır, rütubətsevəndir, çöl-çəmən torpaqlarında yaxşı bitir.

Lənkəran ovalığında, bağlarda, həyətyanı sahələrdə əkilib bеcərilir.

Хarratlıq məmulatlarının istеhsalatında və oyma naхış işlərində istifadə olunur. Dеkorativ və mеyvə ağacı kimi əkilib yеtişdirilir. Mеyvələri öz ətri ilə fərqlənir.

Jabloň nízká (Malus pumila) je druh opadavých listnatých stromů z čeledi růžovitých. Přirozeně se vyskytuje v oblasti od Střední Asie po jihovýchodní Evropu. Jsou to stromy nebo keře vysoké přibližně 5 metrů. Tvoří oválnou korunu, jejich převisající větve nemají kolce. Druh má tendenci podrážet a rozšiřovat se kořenovými výběžky.[1]

Česká synonymaː

Některé variety jsou v zahradách a parcích používány jako okrasné dřeviny, především pro kvetení a plody. Například kultivary Malus pumila 'Balleriana', 'Liset', 'Profusion', 'Roseta', 'Rudolph'.[2]

Hospodářský význam má varieta janče svatometské (Malus pumila var. paradisiaca) a duzén (Malus pumila var. praecox). Tyto variety jsou používány jako podnože pro šlechtěné odrůdy jabloní, jsou označovány jako podnože řady M.[1]

Jabloň nízká (Malus pumila) je druh opadavých listnatých stromů z čeledi růžovitých. Přirozeně se vyskytuje v oblasti od Střední Asie po jihovýchodní Evropu. Jsou to stromy nebo keře vysoké přibližně 5 metrů. Tvoří oválnou korunu, jejich převisající větve nemají kolce. Druh má tendenci podrážet a rozšiřovat se kořenovými výběžky.

Almindelig æble (Malus domestica)[1], også kaldet spiseæble eller sødæble) er et almindeligt dyrket frugttræ, der også findes forvildet i hegn og skovbryn. De gule, røde eller grønne frugter (æbler) er til forskel fra skovæble altid over 3 centimeter i diameter og træet er uden torne.

Almindelig æble er et mellemstort, løvfældende træ med en rund, tætgrenet krone. Stammen er ret kort, og hovedgrenene er svære med mange sidegrene. Kortskuddene kan blive tornagtige (uden at være rigtige torne!). Barken er først rød med grålig hårbeklædning, i det mindste på den yderste halvdel af skuddet. Senere bliver barken gråbrun med lyse korkporer. Til sidst er den grå og opsprækkende i smalle furer. Knopperne er spredte, afrundede og røde med grå hårbeklædning.

Bladene er ovale til ægformede eller næsten runde med en rundtakket kant. Stilken er kort. Oversiden er mørkegrøn og let håret i begyndelsen, mens undersiden er grå af den tætte hårklædning. Blomsterknopper findes kun på de knudrede kortskud ("frugtsporer"), og de er helt dækket af grå hår. Blomstringen sker i maj måned, hvor de hvide til svagt lyserøde blomster sidder i små bundter på 4-5. Frugterne er de velkendte æbler. Frøene spirer villigt, men de giver typisk træer, som kun i ringe grad ligner forældreplanterne (se nedenfor under vildæble). De triploide sorter ('Belle de Boskoop' og 'Bramley Seedling') sætter ikke frø.

Rodnettet bestemmes af den valgte grundstamme. 'M27' har en yderst svag rod, 'MM106' har en middelstærk rod, og vildstammer danner en kraftig rod. Vildstammeroden svarer til træets eget rodnet, der består af få, men svære hovedrødder, der når langt ned og ud. Siderødder og finrødder ligger højt i jorden. Træet skaber jordtræthed.

Højde × bredde og årlig tilvækst: 12 × 6 m (30 × 20 cm/år).

Almindelig æble findes i talrige sorter, der er resultatet af årtusinders arbejde med udvælgelse og krydsning. Træet har altså intet hjemsted, men dets vilde stamformer hører alle hjemme i de blandede løvskove fra Østeuropa over Lilleasien og Kaukasus til Elburzbjergene og Centralasien. Nye undersøgelser tyder overbevisende på, at almindelig æble har sin oprindelse i Kazakhstan, for dér findes den største genetiske variation.[2] Alle disse steder foretrækker træets vildformer en jordbund, der er rig på humus og mineraler, og som er konstant fugtig.

Der findes et hav af æblesorter. Nogle er bedre end andre til bestemte formål, og desværre producerer planteskolerne helst de sorter, som er velegnede i frugtplantager. De følgende kan anses for at have bevist deres duelighed under private haveforhold, men de kan, som antydet, være svære at skaffe.

Madæbler:

Bordfrugt/spiseæbler:

Vildæble er frøplanter af de almindelige spiseæbler, og planten er et op til 8 m højt træ. Vildæble kan gro på næsten alle jordtyper, men bedst på frodig lerjord. Træet bør ikke bruges på våd eller meget tør bund. Det tåler kystklima godt. Vildæble blomstrer fra sidst i maj til ind i juni. Det er velegnet til kanter, den indre del af skovbryn og i vildtplantninger samt til læplantninger. De store, sure og grønne æbler holder langt hen på vinteren eller helt hen til den følgende sommer, og de ædes ofte af hjortevildt og fugle. Skud og grene er blandt den mest eftertragtede vinterføde for hjortevildt og harer.

Vildæble må ikke forveksles med skovæble, også kaldet abild, som er en anden art (Malus sylvestris).

Almindelig æble (Malus domestica), også kaldet spiseæble eller sødæble) er et almindeligt dyrket frugttræ, der også findes forvildet i hegn og skovbryn. De gule, røde eller grønne frugter (æbler) er til forskel fra skovæble altid over 3 centimeter i diameter og træet er uden torne.

Der Kulturapfel (Malus domestica Borkh., Synonym: Pyrus malus L.) ist eine weithin bekannte Art aus der Gattung der Äpfel in der Familie der Rosengewächse (Rosaceae). Er ist eine wirtschaftlich sehr bedeutende Obstart. Die Frucht des Apfelbaumes wird Apfel (regional als Appel) genannt.

Äpfel werden sowohl als Nahrungsmittel im Obstbau als auch zur Zierde angepflanzt. Außerdem wird ihnen eine Wirkung als Heilmittel zugeschrieben. Als die Frucht schlechthin symbolisieren Apfel und Apfelbaum die Themenbereiche Sexualität, Fruchtbarkeit und Leben, Erkenntnis und Entscheidung sowie Reichtum.

Der Kulturapfel ist ein sommergrüner Baum, der im Freistand eine etwa 8 bis 15 Meter hohe, weit ausladende Baumkrone ausbildet. Tatsächlich ist diese Wuchsform selten zu beobachten, da die einzelnen Sorten in Verbindung mit ihren Unterlagen eine davon oft stark abweichende Wuchshöhe zeigen (als Extremfälle der Hochstamm und der Spindelbusch), die darüber hinaus durch den Schnitt nicht zur Ausprägung kommt.

Die wechselständig angeordneten Laubblätter sind oval, rund bis eiförmig oder elliptisch, meist gesägt, selten ganzrandig und manchmal gelappt.

Das Holz des Kulturapfels gleicht dem des Holzapfels, hat einen hellrötlichen Splint und einen rotbraunen Kern. Es ist hart und schwer und zählt zu den heimischen Edelhölzern. Die besten Stücke liefern die mächtigen Stämme der Mostapfelbäume.

Einzeln oder in doldigen Schirmrispen stehen die Blüten. Die fünfzähligen, radiären Blüten sind bei einigen Sorten halbgefüllt oder gefüllt, meist flach becherförmig, häufig duften sie und haben meist einen Durchmesser von zwei bis fünf Zentimeter. Die fünf Kronblätter sind weiß oder leicht rosa, im knospigen Zustand immer deutlich rötlich. Je nach Blüte sind viele Staubblätter und fünf Fruchtblätter vorhanden.

Der Apfelbaum blüht in Zentraleuropa meist im Mai.[2] Der Blühbeginn des Apfels markiert im phänologischen Kalender den Beginn des Vollfrühlings. Durch die Protokollierung der örtlichen Verschiebungen der Apfelblüte können Rückschlüsse auf allgemein beobachtbare Klimaveränderungen gezogen werden.[3] Insofern gilt sie als Indikator für die globale Erwärmung. Seit den 1950er-Jahren hat sich dadurch die Apfelblüte etwa in Norddeutschland um knapp zwei Wochen nach vorne verlagert.[4]

Die Apfelblüte ist eine typische Bienenblüte. Dass fünf Prozent der Blüten bestäubt zu Früchten heranreifen, reicht bei Apfel oder Birne für eine Vollernte, während bei Steinobst der entsprechende Anteil 25 Prozent beträgt.[5]

Das fleischige Gewebe (Fruchtfleisch) des Apfels, das normalerweise als Frucht bezeichnet wird, entsteht nicht aus dem Fruchtknoten, sondern aus der Blütenachse. Die Biologie spricht daher von Scheinfrüchten. Die Apfelfrucht – für die der Apfel typisch ist – ist eine Sonderform der Sammelbalgfrucht. Ein Balg besteht aus einem Fruchtblatt, das an einer Naht mit sich selbst verwächst. Innerhalb des Fruchtfleisches entsteht aus dem balgähnlichen Fruchtblatt ein pergamentartiges Gehäuse. Im Fruchtfleisch selbst sind höchstens noch vereinzelt Steinzellennester enthalten.

Äpfel reifen nach der Ernte nach. Sie zählen zu den klimakterischen Früchten. Ein beigelegter Apfel und eine Abdeckung lassen Bananen und andere Früchte schneller reifen. Grund ist das gasförmige Pflanzenhormon Ethen, das bei der Nachreifung freigesetzt wird. Aufgrund der enzymatischen Bräunung wird das Fruchtfleisch dort, wo es nicht durch die Schale geschützt ist, je nach Sorte und Vitamin-C-Gehalt verschieden schnell braun. Das ist gesundheitlich unbedenklich, beeinflusst jedoch die medizinische Heilwirkung.[6][7] Braune Fäule in Zusammenhang mit Schimmelpilzen führt zu erhöhtem Patulin-Gehalt in Apfelsaft.

Beim Rohverzehr wird das harte Kerngehäuse zumeist verschmäht. Es wird oft gesagt, dass Äpfel nicht ganz gegessen werden sollen, da ihre Kerne (die Samen) Blausäure enthalten. Der Blausäuregehalt von Apfelsamen ist allerdings sehr gering, sortenspezifisch verschieden und unbedenklich beim Essen von wenigen ganzen Äpfeln.

Die Chromosomenzahl beträgt 2n = 34 oder 3n=51.[8]

Der Kulturapfel ist ein winterkahler Laubbaum. Die Wurzel trägt eine VA-Mykorrhiza.[9]

Die Blüten sind vorweibliche, duftende „Nektar führende Scheibenblumen“. Die Blüten werden besonders reichlich von Bienen besucht. Der Nektar wird vom Blütenbecher abgegeben und ist mit 75 Prozent extrem zuckerreich. Fremdbestäubung ist obligat. Einige Apfelsorten lassen sich noch nicht einmal untereinander kreuzen (Intersterilität). Auch pollenfressende Käfer besuchen die Blüten.[9]

Apfelfrüchte sind das Verwachsungsprodukt von fünf balgfruchtartigen, meist zweisamigen Einzelfrüchten, die sowohl das pergamentartige Gehäuse wie auch den Blütenbecher bilden. Letzterer wächst bei der Fruchtreife zu dem mächtigen, zuckerreichen (bis ca. 13 Prozent) „Fruchtfleisch“ heran. Es erfolgt vor allem Verdauungsausbreitung durch den Menschen, dazu Schwimmausbreitung ganzer Äpfel und Bearbeitungsausbreitung z. B. durch Nagetiere. Die bekannte Braunfärbung der Schnittflächen eines Apfels wird durch die Oxidation des Polyphenols Chlorogensäure hervorgerufen. Reifende Äpfel produzieren gasförmiges Ethen, das die Reifung anderer Früchte in der Nähe fördert; dies kann auch zu deren vorzeitigen Verderb führen. Die Samen des Apfels befinden sich normalerweise in einer Samenruhe d. h., sie werden erst keimfähig, wenn die unter der Samenschale befindlichen Hemmstoffe in einem feuchten Keimbett abgebaut sind.[9]

Weil die Kultursorten nicht samenbeständig sind, erfolgt die Vermehrung überwiegend durch Veredelung (vegetative Vermehrung). Gewöhnlich werden die gewünschten Sorten auf eine gutwüchsige Unterlage gepfropft. Verwilderte Apfelbäume vermehren sich auch reichlich durch Wurzelsprosse.[9] Die Marssonina-Blattfallkrankheit ist eine Infektionskrankheit des Kulturapfels.

Der Kulturapfel ist eine Zuchtform, die nach bisherigen Darstellungen durch Kreuzung des noch wild vorkommenden Holzapfels (Malus sylvestris) mit Malus praecox oder Malus dasyphylia entstanden ist. Neuere genetische Untersuchungen weisen aber auf eine Abstammung vom Asiatischen Wildapfel (Malus sieversii) mit Einkreuzungen des Kaukasusapfels (Malus orientalis) oder des Kirschapfels (Malus baccata) hin.[10][11] Die drei eingangs genannten Wildapfelsorten sind wahrscheinlich bereits recht früh eingekreuzt worden. Gesichert ist, dass im Kaukasus und im Mittleren Osten bereits vor 4000 Jahren Äpfel angebaut wurden.[11]

Die ursprüngliche Heimat des Kulturapfels liegt demnach in Asien. In der heute Almaty genannten Großstadt am Tian Shan wurden nach kasachischen Angaben schon vor 6.000 Jahren Früchte gehandelt, die dem heutigen Kulturapfel glichen.[12] Die größte Stadt in Kasachstan, Almaty hieß früher Alma-Ata was in kasachisch „Großvater der Äpfel“ bedeutet.[11]

Über die Verbreitung des Apfelbaums von Asien nach Mitteleuropa ist nichts Näheres bekannt, möglicherweise gelangte er über Handelswege hierher, da die Frucht als lebensverlängerndes Heilmittel galt. Auch Schwarzwild und Pferde haben wohl zur Verbreitung durch Samen beigetragen.[13]

Die durchschnittliche Frucht des Kulturapfels besteht zu 85 Prozent aus Wasser.

Das komplexe Aroma des Apfels setzt sich aus zahlreichen Stoffen zusammen. In der quantitativen Zusammensetzung der Aromastoffe des Apfels gibt es große sortenbedingte Unterschiede. Im Wesentlichen sind Ester, Aldehyde und Alkohole am Apfelaroma beteiligt. Zu den wichtigsten Estern zählen Ethyl-2-methylbutyrat, Ethylbutyrat, 2-Methylbutylacetat, Butylacetat, Hexylacetat und 2-Methylbuttersäuremethylester.[15] Zu den Aldehyden, die zum Teil erst beim Zerkleinern oder Kauen im Mund durch eine sehr schnelle enzymatische Umwandlung von Fettsäuren entstehen und die häufig auch als Grünnoten (Geschmack nach grünen Äpfeln wie Granny Smith) bezeichnet werden, gehören Hexanal und 2-Hexenal. Bei den Alkoholen sind 1-Butanol, 2-Methylbutanol, 1-Hexanol und 2-Hexenol von Bedeutung. Weitere Schlüsselaromastoffe des Apfels sind β-Damascenon und α-Farnesen.

Das Apfelaroma wird sehr stark von der Apfelsorte, klimatischen Faktoren, dem Erntezeitpunkt und der Lagerdauer nach der Ernte beeinflusst. Im Stadium der frühen Reife sind häufig kaum Ester nachweisbar. Bei länger gelagertem Obst kann der Estergehalt je nach Sorte dramatisch ansteigen. Diese Aromabildung während der Nachreifung wird aber nur bis zu einem bestimmten Ausmaß als angenehm und harmonisch empfunden. In der Endphase werden die Äpfel als überreif und parfümiert sensorisch abgelehnt. Die Nachreifung und die damit verbundene Aromabildung können durch Kühlung und Lagerung unter kontrollierter Atmosphäre gestoppt oder verlangsamt werden, wodurch es möglich geworden ist, über ein ganzes Jahr hinweg sensorisch akzeptable Apfelqualitäten anzubieten. Äpfel mit einer ausgeprägten natürlichen Wachsschicht auf der Schale (wodurch ein Apfel durch Polieren glänzend gemacht werden kann) sind wegen dieser Schicht, die ein Austrocknen verhindert, länger haltbar.

Bereits die Kelten und Germanen verarbeiteten die wohl kleinen und harten Früchte des einheimischen Apfels. Sie verkochten das Obst zu Mus und gewannen Most daraus. Den Saft vergor man zusammen mit Honig zu Met. Daneben ist sein Nektar mit 9 bis 87 Prozent Zuckergehalt und einem Zuckerwert von bis zu 1,37 mg Zucker je Blüte pro Tag für die Bienen eine wichtige Tracht bei der Honigerzeugung.[16]

Der Kulturapfel hat im Obstbau überragende Bedeutung. Das liegt daran, dass er von allen heimischen Obstarten am vielfältigsten verwendbar ist. Es gibt vom Apfel daher die weitaus meisten Zuchtformen; er gilt in unseren Breiten als das „Obst“ schlechthin.

Die älteste dokumentierte Sorte des Kulturapfels ist vermutlich der Borsdorfer Apfel, der bereits 1170 von den Zisterziensern erwähnt wurde.

Um 1880 waren mehr als 20.000 Apfelsorten weltweit in Kultur, davon allein in Preußen über 2.300 Sorten. Seit dem Beginn der Industrialisierung bis ins frühe 20. Jahrhundert wurde vielfältiger Obstbau und Züchtung zur Versorgung der städtischen Großräume politisch gefördert und motiviert. Unterstützt durch Obstbauliteratur und Pomologenvereine konnte eine große regionale Sortenvielfalt dokumentiert und erhalten werden.

Heute gibt es in Deutschland ungefähr 1.500 Sorten, von denen aber lediglich 60 wirtschaftlich bedeutend sind. Die aufwendige Sortenkunde und der Erhalt alter oder nicht mehr industriell genutzter Sorten wird heute von verschiedenen Vereinen betrieben.

Im Gartenhandel und bei Direktvermarktern sind derzeit nur noch etwa 30 bis 40 Sorten erhältlich – Tendenz sinkend. In den Auslagen der Supermärkte schrumpft das Angebot sogar auf fünf bis sechs globale Apfelsorten zusammen. Neben der Vielfalt des Angebotes gehen zunehmend auch innere Qualitäten der Sorten verloren. Neuerdings spricht man auch von Markenäpfeln, sogenannten Clubsorten, wie zum Beispiel 'Pink Lady', die nur in Lizenz verkauft werden dürfen.

Die verschiedenen Apfelsorten werden in die Apfelreifeklassen Sommer-, Herbst- und Winterapfel unterschieden.

Apfelsortenvergleich auf der Landesgartenschau in Öhringen (2016)

Säuregehalt verschiedener Apfelsorten

Zuckergehalt verschiedener Apfelsorten

Vitamin-C-Gehalt verschiedener Apfelsorten

Seine größte Bedeutung hat der Apfel als Tafelapfel; in Deutschland macht er um die 75 Prozent der Gesamternte aus.[17] Die Sorten, die im Großanbau normalerweise als Tafelobst angebaut werden, sind auf die Anforderungen des Frischmarktes im Lebensmitteleinzelhandel ausgerichtet. Die Äpfel müssen knackig und saftig sein sowie gut zu lagern und zu transportieren.[18] Viele lokale Sorten werden diesen Anforderungen nicht gerecht, daher werden im Erwerbsobstbau nur wenige Sorten – diese aber oft in weltweiter Verbreitung – angebaut.

Wegen des hohen Ertrags, gepaart mit dem hohen Wasseranteil der Früchte ist der Apfel das Saftobst schlechthin, der überwiegende Anteil der Jahresapfelernte wird als Saftapfel verflüssigt: 450 Firmen in Deutschland produzieren alljährlich eine Milliarde Liter Apfelsaft.[19] Unter den 41 Litern Fruchtsäften und -nektaren, die jeder Bundesbürger laut deutschem statistischen Bundesamt pro Jahr konsumiert, ist der Apfelsaft Spitzenreiter mit einem jährlichen Pro-Kopf-Verbrauch von 11,7 Litern. Danach erst kommt Orangensaft mit 9,8 Litern. Die Zahlenverhältnisse sind in Österreich und der Schweiz ähnlich.

In Europa machen drei gängige Apfelsorten nahezu 70 Prozent des Gesamtangebotes am Apfelfrucht-Markt aus:[20]

Weitere wirtschaftlich bedeutende Sorten, die im Erwerbsobstbau mit geringen Kosten angebaut werden können (grob absteigend nach wirtschaftlicher Bedeutung sortiert):

Unter der Bezeichnung „Alte Apfelsorte“ versteht man Sorten, die vor etwa 1940 entstanden sind. Manche sind – aufgrund lokaler klimatischer oder kultureller Umstände – regional noch von Bedeutung, manche nurmehr vereinzelt in Obstbauversuchsanlagen zu finden.

Der Apfel ist die Obstart, die über die längste Zeit des Jahres verfügbar war. Daher hatten alte Bauerngärten meist eine ganze Serie von Apfelbäumen stehen, die durch ihren optimalen Reifegrad eine kontinuierliche Versorgung mit Obst vom Frühsommer bis in das nächste Frühjahr sicherstellten.

Alte Tafelapfelsorten mit besonders angenehmem Geschmack, die heute nicht mehr im Erwerbsobstbau angebaut werden, da sie wenig ertragreich, kleinfrüchtig oder schwer zu kultivieren sind, sind etwa:

Einige Apfelsorten wurden speziell als Lagerapfel genutzt. Dieses Lagerobst wurde früher in feuchten und kühlen Kellern eingelagert. Heutzutage ist das in unseren modernen Häusern nur noch schwer möglich. Beim Apfel gibt es Sorten, die bis in den Mai hinein nicht verderben. Spät geerntete Sorten bezeichnet man als Winterapfel, diese sind dann meist erst nach Weihnachten genießbar.

Als Wirtschaftsapfel bezeichnet man Sorten, die vor allem zum Verarbeiten für Saft, Most, als Backapfel oder Kochapfel vorgesehen sind und meistens keine Tafeläpfel sind. Als Beispiele wären hier Jakob Lebel, Rheinischer Winterrambur oder Westfälischer Gülderling zu nennen.

Bei der Apfelsaftherstellung ist ein hoher Säureanteil wichtig, weshalb man dabei auch auf die säurehaltigeren älteren Sorten aus dem Streuobstanbau und aus Privatgärten zurückgreift, zumal ein erwerbsmäßiger Anbau von speziellen Äpfeln zur Safterzeugung in Mitteleuropa kaum rentabel ist. Der allergrößte Anteil des in Deutschland verkauften Apfelsaftes entstammt säurearmen Sorten des Erwerbsobstbaus, aus diesem Grunde wird dem Saft Ascorbinsäure zugesetzt.

Auch als Kochobst ist der Apfel hervorragend geeignet. Kochapfelsorten sind meist sehr süß und trotzdem auch ziemlich sauer, und sie verlieren ihre feste Konsistenz und ihr Aroma beim Erhitzen nicht. So gibt es etwa den Behm-Apfel, der seinen Namen den berühmten Mehlspeisen der Böhmischen Küche (in Bereichen außerhalb Ostösterreichs eher als Wiener Küche bekannt) verdankt, allen voran der zu internationalem Ruf gelangte Apfelstrudel.

Der Apfel ist das ideale Obst zum Einkochen, da er durch seinen hohen Pektingehalt als natürliches Konservierungs- und Geliermittel wirkt. Außer für Apfelmus wird er verwendet bzw. zugesetzt, um andere Obstarten einkochtauglich zu machen. Auch die Früchte vieler Wildäpfel kann man entsaften und zu Apfelgelee verarbeiten; einige sind aber ausschließlich gekocht genießbar.

Als Heilpflanze taucht der Apfel bereits in einer alten babylonischen Schrift aus dem 8. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert auf, die die Pflanzen des Heilkräutergartens des Königs Marduk-apla-iddina II. aufzählt. Auch die mittelalterliche Medizin schrieb dem Apfel allerlei heilkräftige Wirkungen zu. Die Mehrzahl der Früchte der damaligen Apfelsorten dürfte für den heutigen Geschmack noch reichlich sauer, gerbstoffhaltig und holzig gewesen sein. Häufig liegt noch im Dunkeln, wie, wann und welche Teile der Apfelpflanze genutzt wurden.

Apfelfaser ist ein Ballaststoff, der aus entsafteten und getrockneten Äpfeln gewonnen wird. Er enthält einen hohen Anteil an Pektinen.

Der regelmäßige Verzehr von Äpfeln reduziert das Risiko, an Herz- und Gefäßerkrankungen, Asthma und Lungenfunktionsstörungen, Diabetes mellitus und Krebs zu erkranken. Bei den Krebserkrankungen sind dies insbesondere Darm- und Lungenkrebs. Mehrere Studien, Tierversuche und epidemiologische Daten kommen zu dem Schluss, dass der regelmäßige Verzehr von Äpfeln eine krebsvorbeugende Wirkung habe. Dafür sind vermutlich die in Äpfeln enthaltenen Pektine und Polyphenole, wie beispielsweise Quercetin, verantwortlich. Auch in Tierversuchen konnten die epidemiologischen Daten bestätigt werden. Mäuse und Ratten mit einer Nahrungsergänzung aus Äpfeln entwickelten bis zu 50 Prozent weniger Tumoren. Auch waren die Tumoren kleiner und die Metastasierung schwächer ausgeprägt als bei den Tieren, die keine Äpfel in der Nahrung hatten. Der gleiche Effekt stellte sich bei Apfelsaft ein, wobei hier der trübe Apfelsaft wirksamer war. Vermutlich sind hier die Procyanidine, die in trübem Apfelsaft in hoher Konzentration vorliegen, die Ursache.[22] Apfeltee wird als Getränk aus getrockneten oder frischen Apfelstücken zubereitet.[23] Das englische Sprichwort An apple a day keeps the doctor away fasst die gesundheitsfördernde Wirkung der Apfelfrucht zusammen.

Untersuchungen haben immer wieder gezeigt, dass Äpfel aus konventioneller Landwirtschaft, im Gegensatz zu Äpfeln aus ökologischer Landwirtschaft, in der Regel mit mehreren Pestiziden gleichzeitig belastet sind.[24]

Dem deutschen Apfel ist seit 2010 der 11. Januar gewidmet. Der Tag des deutschen Apfels wurde von allen wichtigen Apfel-Erzeugerorganisationen Deutschlands ins Leben gerufen. Initiatoren unterstützen den Aktionstag, der im Rahmen der Verbraucherkampagne „Deutschland – Mein Garten“ stattfindet.[25] Am 11. Januar 2010 wurden kostenlos 40.000 Äpfel in den fünf Großstädten Berlin, Hamburg, Köln, Leipzig und München verteilt. Ziel der Maßnahme war es, auf deutsche Äpfel aufmerksam zu machen und das Wissen um die verschiedenen Sorten und ihre Anwendungsbereiche zu vergrößern.

In Österreich wird jedes Jahr am zweiten Freitag im November der Tag des Apfels gefeiert. Damit soll auf den hohen Vitamin- und Mineralstoffgehalt, die Fähigkeit als Durstlöscher und die positive gesundheitliche Wirkung aufmerksam gemacht werden.

Im Jahr 2020 wurden laut Ernährungs- und Landwirtschaftsorganisation (FAO) der Vereinten Nationen weltweit etwa 86.442.716 t Äpfel geerntet. Die 10 größten Produzenten ernteten zusammen 76,0 % der Welternte. Die Volksrepublik China allein brachte 46,9 % der Ernte ein. Die größten europäischen Produzenten waren Polen, Italien und Frankreich. Zum Vergleich: In Deutschland wurden im selben Jahr 1.023.320 t, in Österreich 258.220 t und in der Schweiz 192.443 t geerntet.[26]

Die größten Exporteure waren 2020 die Volksrepublik China (1.058.094 t), gefolgt von Italien (935.424 t) und den USA (808.118 t).[27]

Es gehört zu den frühen kulturellen Errungenschaften, die Nutzung des Apfels als Nahrungsmittel von Zufallsfunden auf eine Pflege des Apfelbaums umzustellen und könnte älter sein als die typischen ackerbaulichen Methoden: Sie lässt sich auch in nichtsesshafter Lebensweise durchführen.

Den Obstbau, so wie wir ihn heute kennen, haben in Mitteleuropa die Römer eingeführt. Sie begannen laut Quellenlage mit der gezielten Züchtung und brachten die Kunst des Pfropfens und Klonens in ihre Kolonien und Provinzen. Seit dem 6. Jahrhundert hat man den Apfel in Mitteleuropa angebaut. Seit dem 16. Jahrhundert wurde er dann zu einem Wirtschaftsgut.

In Deutschland legte der Obstbaupionier Otto Schmitz-Hübsch 1896 die erste Apfelplantage an und führte zugleich die Dichtpflanzung mit Niederstammbäumen ein.

Die Kultur gelingt am besten in mäßig nährstoffreichem, feuchtem, aber wasserdurchlässigem Boden in voller Sonne. Äpfel sind frosthart. Die Keimlinge (aus den Kernen = Samen) eines Apfels sind nie sortenrein. Für die Erhaltung und Zucht von Apfelsorten eignen sich daher nur die unterschiedlichen Techniken der vegetativen Vermehrung.

Diese Methode fügt ausgewählte Partner zusammen, um gewisse Eigenschaften zu erhalten. Dazu wird meist eine Unterlage, also eine Sorte, die ausschließlich für den Wurzel- oder Stammaufbau zuständig ist, mit einem einjährigen Trieb der gewünschten Edelsorte veredelt. Diese Edelsorte bildet mit ihren Zweigen in den folgenden Jahren die Baumkrone und die fruchttragenden Baumteile.

Bei Sorten, die entweder zu schwach wachsen, nicht gerade wachsen oder nicht frosthart sind, hat sich die Zwischenveredlung durchgesetzt. Auf die gewünschte Wurzelunterlage wird ein Stammbildner mit einer der Methoden der Pflanzenveredlung veredelt (meist okulieren), um dann, wenn das Bäumchen die gewünschte Stammhöhe erreicht hat, mit einer oder auch mehreren Apfelsorten in der Baumkronenhöhe veredelt zu werden.

Als Unterlagen standen früher ausschließlich aus Kernen gezogene Sämlinge zur Verfügung (siehe auch bei den Sorten Bittenfelder und Jakob Fischer), mittlerweile wird mit speziellen Unterlagenzüchtungen eine für den Erwerbsobstbau geeignete Pflanzencharakteristik erzielt. Aus Apfelkernen gezogene Unterlagen bilden fast immer mächtige Wurzeln und Stämme aus, tragen erst nach 8 bis 10 Jahren Früchte und sind Grundlage historischer Streuobstanlagen oder Einzelbäume. Die nach den gewünschten Eigenschaften selektierten und vegetativ vermehrten Unterlagen für den Erwerbsobstbau bilden kaum Holz (solche „Bäume“ brauchen lebenslang Stützkonstruktionen), wurzeln flach, sodass in trockenen Perioden künstliche Bewässerung notwendig ist, aber bringen bereits nach wenigen Jahren einen höheren Fruchtertrag je Fläche als die Hochstämme.

Zur Vermehrung von Unterlagen werden Apfelkerne im Herbst im Saatbeet gesät. Sie müssen durch Kälteeinwirkung keimfähig gemacht (stratifiziert) werden. Apfelkerne verfügen häufig über keimhemmende Substanzen, die erst durch Gärungsprozesse abgebaut werden – Kerne aus Pressgut (Trester) eignen sich daher besonders für die Keimung, während Kerne, die man einfach beim Apfelessen zur Seite legt, selten keimen. Die kleinen Apfeltriebe können dann in den folgenden Jahren veredelt werden.

Die angebauten Apfelsorten werden, sobald sie als Sorte stabil und interessant sind, durch vegetative Vermehrung, Klonen (ungeschlechtliche Vermehrung, die von einem geschlechtlich gezüchteten Individuum ausgeht) oder durch Veredelung/Pfropfen auf einen Apfelstamm (meist auch nur auf einen bewurzelten Zweig – wegen geringerer Kosten) vermehrt.

Die Gefahr ist groß, dass in Vergessenheit geratene Sorten unwiederbringlich verloren gehen. Im Prinzip reicht zwar ein Apfelbaum aus, um eine Apfelsorte zu erhalten, da jeder Apfel durch Veredelung oder Klonen in beliebiger Zahl reproduziert werden kann. Jedoch ist ein Apfelbaum mit etwa 100 Jahren Lebensdauer nicht sehr langlebig (im Vergleich: Linden z. B. werden bis zu 2.000 Jahre alt).

Heutzutage wird versucht, den in der hohen Sortenvielfalt steckenden genetischen Reichtum durch Bestimmen und Sammeln alter Sorten zu erhalten und zu vergrößern oder zumindest die Verarmung zu verlangsamen. Insbesondere wäre dieser genetische Reichtum in der Neuzüchtung sehr wichtig. Im Moment wird dies aber nicht praktiziert. In Deutschland leistet unter anderem das Julius Kühn-Institut in Dresden-Pillnitz einen wertvollen Beitrag zur Sammlung alter und neuer Apfelsorten; für Großbritannien ist hier etwa die National Fruit Collection in Brogdale, einem Vorort von Faversham, zu nennen. Das Erhalten alter Apfelsorten ist sonst kommerziell schlecht nutzbar und eine solche Aufgabe mit industriellen Methoden kaum zu bewältigen; für alte Apfelsorten sind Streuobstwiesen daher ein wichtiger Anbauort.

Der Feuerbrand ist die derzeit (2008) bei weitem folgenschwerste Bedrohung für den Obstbau in Mitteleuropa – besonders die heutigen Erwerbsbausorten zeigen sich als hochanfällig, er befällt aber auch viele der alten Sorten aggressiv.

Folgende Schädlinge und Krankheiten können im Apfelanbau Probleme hervorrufen:

Auch durch Sonnenbrand werden Früchte geschädigt, wogegen Kaolin als Sonnenschutzmittel in wässriger Suspension ausgebracht werden kann.[28]

Darüber hinaus können im ganzen Obstbau auch Wind-, Schneebruch oder Hagelschlag sowie extreme Spätfröste regional zu gravierenden Ernteausfällen führen.

In einigen Regionen sind auch Streuobstwiesen und Apfelbaum-Alleen verbreitet.

Die wirtschaftlich bedeutendsten Apfelanbaugebiete Europas sind die Normandie und die Poebene. Im gesamten Mittelmeerraum wird für den Export angebaut, klassische Obsterwerbsanbaugebiete in Mitteleuropa sind:

Von der Südhalbkugel – vor allem aus Neuseeland, Chile und Argentinien – werden Äpfel in großen Mengen importiert und decken im Frühling und Sommer den größten Teil der Apfelnachfrage der Nordhalbkugel.

2015 wurden in Deutschland 973.000 Tonnen Äpfel geerntet, was 13 Prozent unter dem Vorjahreswert liegt, jedoch etwas über dem langjährigen Durchschnitt von 972.000 Tonnen.[29] Im Folgejahr 2016 stieg die Erntemenge auf 1.032.090 Tonnen an. 2017 fiel die Erntemenge auf ein Rekordtief, es wurden lediglich 596.700 Tonnen geerntet. Schuld war vor allem eine kurze Frostperiode während der Obstblüte im April. Dem Rekordtief folgte 2018 jedoch direkt ein Rekordhoch mit 1.198.500 Tonnen.[30]

Die Apfelpreise der vier größten produzierenden Länder in der EU (Deutschland, Frankreich, Polen und Italien) liegen im langjährigen Schnitt bei 0,68 Euro / Kilogramm.[31]

Das größte Obstanbaugebiet in Deutschland ist das Alte Land entlang des südlichen Elbufers in Niedersachsen und zum kleinen Teil auf Hamburger Landesgebiet liegend. Die Anbaufläche im Alten Land beträgt rund 10.700 Hektar. Im Alten Land wurde bereits im 17. Jahrhundert Obst angebaut. Zweitgrößte Obst- bzw. Apfelregion in Deutschland ist die Bodenseeregion mit rund 8500 Hektar Anbaufläche. Rund 1.200 Obstbauern betreiben hier Obstanbau und erzeugen 1,5 Milliarden Bodensee-Äpfel jährlich.[32] Am Bodensee gehören Jonagold, Elstar, Idared und Gala, aber auch alte Sorten wie Cox Orange und Schöner aus Boskoop, zu den häufigsten und beliebtesten Kulturapfelsorten, die von den vergleichsweise hohen Sonnenperioden profitieren. Auch die neueren Sorten Cameo und Fuji wurden seit 2013 vermehrt angebaut. Sie sind Lagersorten, die im September und Oktober geerntet werden und bis zum Sommer des Folgejahres verfügbar sind.[32]

1960 setzte die Rationalisierung und Intensivierung im Obstbau ein, und in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren wurden massenhaft Bäume gefällt und Obstgärten mit Baumreihen angelegt, die heute überwiegend mit Hagelschutznetzen, meist reffbar, ausgestattet sind.

Von österreichweit 6000 Hektar Anbaufläche liegen 80 % in der Steiermark, wo mit insgesamt 220.000 Tonnen mengenmäßig gut 3/4 der Äpfel geerntet werden, und zwar überwiegend aus Plantagen und nur mehr 1/4 aus Streuobstwiesen (Stand 2012). Durch Puch bei Weiz führt die touristisch beworbene Steirische Apfelstraße; im Alpenvorland des westlichen Niederösterreichs liegt das Mostviertel.

Sommer-, Most- und Winteräpfel werden gewaschen und sortiert, als Tafelobst geschüttet oder gelegt vermarktet, zu Mus oder Saft verarbeitet, teilweise vergoren und/oder gebrannt. Äpfel können in Scheiben geschnitten durch Dörren haltbar gemacht werden, was insbesondere in Vorarlberger Haushalten Tradition ist, andererseits industriell für Müslimischungen erfolgt.

Viele Sorten wurden zu besonders großen Exemplaren hin gezüchtet, die komfortabel eher als Spalten gegessen werden. Kleine Äpfel werden, weil im Ganzen schon kindermundgerecht, seit etwa 2002 als Kinderäpfel verkauft. Am Holzspieß mit rotem Zuckerguss kandiert gibt es Äpfel als Jahrmarktdelikatesse.

Die in Österreich mit Abstand am häufigsten angebauten Sorten sind Golden Delicious und Gala; sie wachsen auf etwa der Hälfte der für den Anbau von Winteräpfeln verwendeten Fläche. Weitere wichtige Sorten sind Idared, Jonagold, Braeburn, Elstar und Topaz[33].

Die Haupterntezeit ist im September und Oktober. Sommeräpfel versucht man schon möglichst früh zu ernten und rasch zu vermarkten, Winteräpfel werden hingegen eingelagert und halten sich in Kühlzellen (+3 °C und sauerstofffrei) bis zu einem Jahr.

Äpfel werden gepflückt und geklaubt und kommen schon im Obstgarten in die Großkisten eines der Obstpackhäuser der Region. Kippstapler können diese Kisten sorgsam leeren, die Äpfel fallen ins Wasser, werden gewaschen, nach Durchmesserklassen und Farbe sortiert und getrocknet. Danach werden die Äpfel in kleinere Kisten geschüttet, in Steigen gelegt oder noch kleinteiliger – etwa in 6er-Trays – verpackt.

Pressäpfel können mechanisch etwas gröber behandelt werden und werden daher eher per Kippanhänger mit bis zu 1,5 Meter Schütthöhe von Landwirten zu Obstverwertern oder Obstpressereien geliefert, um eventuell den daraus gewonnenen (Süß-)Most sofort zurück zu übernehmen und ihn selbst in Flaschen abzufüllen oder zu vergären.

Äpfel werden etwa zur Hälfte exportiert (und auch importiert), in Obst- und Gemüsegroßmärkten, in Lebensmittelmärkte, auf Bauern- und Straßenmärkten sowie direkt ab Hof gehandelt. Etwa 5 bis 15 Prozent der Äpfel werden in zertifizierter Bio-Qualität gekauft bzw. angeliefert.

Insbesondere in Streuobstwiesen sind noch 800 alte Sorten vorhanden. Nicht alle davon sind heimischen Ursprungs: So wurde nahe Meißen in Deutschland der Borsdorfer angebaut, wurde später im nahen Böhmen Meißener (míšenské jablko) genannt und kam dann nach Österreich, wo er nun ab 1877 als Winter-Maschanzker dokumentiert ist. Genau genommen sind auch Golden Delicious und Jonathan alte Sorten, weil sie vor 1900 in den USA aufgefunden wurden.

Um Äpfel das ganze Jahr über in gleichmäßiger Qualität im Handel anbieten zu können, gibt es verschiedene Lagerungsverfahren.

Die Reifung der Äpfel wird durch das natürliche „Reifungsgas“ (Phytohormon) Ethen (Ethylen), das sie selbst erzeugen, gesteuert. Deshalb kann bei Lagerung unter kontrollierter Atmosphäre (CA-Lager) die Bildung von Ethen gehemmt bzw. das gebildete Ethen aus der Atmosphäre entfernt und damit eine längere Lagerzeit erreicht werden. Seit einigen Jahren ist in der EU und der Schweiz auch die Verwendung von 1-Methylcyclopropen (Handelsname z. B.: SmartFresh) erlaubt, das Rezeptoren für die Reife-stimulierenden Signale des Ethens im Apfel blockiert. Dadurch wird die Bildung von pflanzeneigenem Ethen gehemmt und die Wirksamkeit von Ethen aus der Umgebungsluft unterbunden.[34][35] Durch solche Verfahren gelagerte Äpfel lassen sich über Monate hinweg als »frisch« vermarkten.[36]

Der Apfel spielt in allen eurasischen Kulturen eine Rolle, und zwar als Symbol der Liebe, Sexualität, der Fruchtbarkeit und des Lebens, der Erkenntnis und Entscheidung, des Reichtums. Aufgrund seiner Verbreitung taucht er in zahllosen Märchen auf und spielt in Mythen und Ritualen eine Rolle. In der Kunst dient ein dargestellter Apfel dann als Sinnbild und hängt in seiner Ikonografie stark vom Kontext ab, in dem er dargestellt ist.

Als uraltes Symbol der Erde wurde der Apfel schon von Anfang an der Offenbarung des weiblichen Prinzips und Göttinnen der Liebe, Sexualität, der Fruchtbarkeit zugeordnet. Bei den Babyloniern war es Ischtar, die mit dem Symbol des Apfels verehrt wurde, bei den Griechen Aphrodite und bei den Germanen Idun.

Der Apfel ist eine gängige alte Umschreibung für die weibliche Brust.

Faustus sagt in der Walpurgisnacht (nach Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

Einst hatte ich einen schönen Traum:

Da sah ich einen Apfelbaum,

Zwei schöne Äpfel glänzten dran;

Sie reizten mich, ich stieg hinan.

Der Äpfelchen begehrt Ihr sehr,

Und schon vom Paradiese her.

Von Freuden fühl ich mich bewegt,

Daß auch mein Garten solche trägt.

Die Konnotation ist aber nicht auf weibliche Aspekte eingeschränkt, im Hohelied Salomos (2, 3) um 1000 v. Chr. heißt es:

„Wie ein Apfelbaum unter den Bäumen des Waldes, so ist mein Liebster unter allen andren Männern! In seinem Schatten möchte ich ausruhn und seine Früchte genießen.“

Eine alte Legende, die in den unterschiedlichsten Kulturen immer wieder auftauchte, ist die Geschichte vom Apfelbaum als Baum des ewigen Lebens.

Der Apfel trägt das Leben in sich, damit auch den Tod.

Der Apfel steht auch für Frucht an sich und dadurch allgemein für Fruchtbarkeit.

Der Apfel steht allgemein für etwas Begehrenswertes, und insbesondere der Prüfung, der Versuchung des Diebstahls zu widerstehen. Die bekannteste Geschichte ist wohl der von Adam und Eva im Garten Eden und ihre Vertreibung daraus, die in der Bibel erzählt wird. Eine Frucht vom Baum der Erkenntnis von Gute und Böse, die Adam und Eva verbotenerweise essen, um wie Gott zu werden, ist der Auslöser. Obwohl in der Bibel nur allgemein von „Frucht“ die Rede ist, hat sich in der westlichen Welt der Gedanke festgesetzt, es sei ein Apfel gewesen. Andere Früchte, die teilweise regional bedingt mit dem Mythos in Verbindung gebracht werden, sind Feige oder Granatapfel, nicht aber die – erst in der Neuzeit nach Europa eingeführte – Tomate, der „Paradiesapfel“ oder Paradeiser.

Der Apfel dient als Emblem der ganzen Thematik vom Paradies, der Unschuld und deren Verlust für den Menschen. Dieser Kontext wird in vielen Märchen, auch im arabischen Raum, verarbeitet. In der christlichen Ikonographie repräsentiert er den gesamten Themenkomplex von Sünde und der Erlösung.

Der Apfel stellt den Menschen vor die Entscheidung zwischen einem geliebten Menschen und persönlichem Vorteil. In einigen Versionen der Sagen wird Wieland der Schmied von einem seiner Brüder unterstützt. Dieser ist ein berühmter Bogenschütze und Jäger. Um ihn zu testen, lässt ihn König Nidung einen Apfel vom Kopf seines Sohnes schießen. Dieser Apfelschuss ist auch von Wilhelm Tell bekannt. Der goldene Apfel ist ein Preis, den es zu zahlen gilt, um einen Ehepartner zu gewinnen. Beispiele sind die Werbung Hippomenes um Atalante, oder in den Grimmschen Märchen Einäuglein, Zweiäuglein und Dreiäuglein, Der goldene Vogel oder Eisenhans.

Der Apfel – insbesondere der vom Baum fallende – symbolisiert den Kontext von Ernte und daraus entstehendem Reichtum und Macht, auch im geistigen Sinne von Erkenntnis.

In der griechischen Mythologie ist der Goldene Apfel im Urteil des Paris und als im Garten der Hesperiden wachsende, ewige Jugend spendende Frucht vertreten.

In der osmanischen Tradition wurde die Bezeichnung „goldener Apfel“ (türkisch kızıl elma) als Synonym für jede der noch nicht eroberten vier christlichen Hauptstädte, die von goldenen Weltkugeln bekrönt wurden, verwendet. Als bedeutende Machtzentren ihrer Zeit waren sie primäre Ziele potentieller Eroberungen durch das expandierende Reich der Osmanen.

In der nordischen Mythologie ist Göttin Idun unter anderem die Hüterin goldener Äpfel.

Schneewittchen wurde von der Königin durch einen Apfel vergiftet, der ein zentrales Symbol und Motiv im Märchen von Schneewittchen ist.

In einem seiner Gemälde verwendet der Künstler René Magritte einen Apfel, um seine Arbeit mit Wörtern und ihren Darstellungen zu untermauern. Das Gemälde trägt den Namen Ceci n'est pas une pomme (Dies ist kein Apfel) und befindet sich derzeit im Musée René Magritte in Brüssel.

Um die englische Bezeichnung Apple als Markenname gab es einen Rechtsstreit zwischen Apple und dem Beatles-Label Apple Records bzw. Apple Corps. Beide haben einen Apfel als Logo.

Die Firma Apple benannte ebenfalls eine Produktreihe (Macintosh) nach einer Apfelsorte. Die Firma soll dieses Symbol gewählt haben, weil die Gründer in ihren jungen Jahren oft in Geldnot waren und regelmäßig Äpfel aßen (die den Vorteil haben, dass sie nahrhaft sind). Manche glauben auch, dass es eine Anspielung auf Isaac Newtons Apfel ist (das ursprüngliche Firmenlogo zeigte übrigens den Apfel, den Baum und Newton, der darunter schlief).

Auf einem Macintosh-Computer war die Apfeltaste die Modifikationstaste, die der Windows-Taste entspricht (seit der Version 10.5 des Systems durch das Zeichen "cmd" ersetzt). Auf Apple-Systemen erhält man das Symbol "Apfel" mit der Tastenkombination Alt+&, aber dieses Symbol verwendet kein reserviertes Zeichen im Unicode und wird daher nicht unbedingt überall als Apfel dargestellt.

Das Logo von Apple Corps Ltd, der Plattenfirma der englischen Band The Beatles, ist ein Granny-Smith-Apfel.

Als Freizeitbeschäftigung werden die noch frischen und somit noch weichen Apfelkerne mit einer Nadel auf einen Faden gezogen. Das Endergebnis wird zu einem Armband oder bei reichlicher Sammlung zu einer Halskette verknotet.[37]

Von einem durch rundum Abbeißen großteils doch unvollständig gegessenem Apfel bleibt der Butz (Butzn, Butzen; Apfelgriebs, Apfelgriebsch, Kitsch(e), Nüssel) über.

Der Kulturapfel (Malus domestica Borkh., Synonym: Pyrus malus L.) ist eine weithin bekannte Art aus der Gattung der Äpfel in der Familie der Rosengewächse (Rosaceae). Er ist eine wirtschaftlich sehr bedeutende Obstart. Die Frucht des Apfelbaumes wird Apfel (regional als Appel) genannt.

Äpfel werden sowohl als Nahrungsmittel im Obstbau als auch zur Zierde angepflanzt. Außerdem wird ihnen eine Wirkung als Heilmittel zugeschrieben. Als die Frucht schlechthin symbolisieren Apfel und Apfelbaum die Themenbereiche Sexualität, Fruchtbarkeit und Leben, Erkenntnis und Entscheidung sowie Reichtum.

Di Aapelbuum (Malus domestica) as en plaant uun det famile faan a ruusenplaanten (Rosaceae). Faan di slach san en hialer rä suurten aptaanj wurden.

Di Aapelbuum (Malus domestica) as en plaant uun det famile faan a ruusenplaanten (Rosaceae). Faan di slach san en hialer rä suurten aptaanj wurden.

Domôcô jabłónka (Malus domestica Borkh.) - to je roscëna - miészańc - dwóch ôrtów jabłónków z rodzëznë różowatëch (Rosaceae Juss.): dzëczi jabłónczi i Malus pumila. Téż człowiek przë tim miészańcu dosc tëli robił. Na Kaszëbach rosce wiele domôcëch jabłónków. Dosc tëli jich mają gbùrze.

Domôcô jabłónka (Malus domestica Borkh.) - to je roscëna - miészańc - dwóch ôrtów jabłónków z rodzëznë różowatëch (Rosaceae Juss.): dzëczi jabłónczi i Malus pumila. Téż człowiek przë tim miészańcu dosc tëli robił. Na Kaszëbach rosce wiele domôcëch jabłónków. Dosc tëli jich mają gbùrze.

De Huusappel (Malus domestica, Borkh.; Pyrus malus, L.) is en Aart ut dat Geslecht vun de Appels. Se is wiethen bekannt un höört to de Familie vun de Rosenplanten (Rosaceae) mit to. Dor hannelt sik dat um en Aart vun Aaft bi, de in den Landbo weertschopplich en grote Rull speelt. De Frucht vun den Boom heet Appel. Huusappels weert to'n Eten in de Aaftbueree un ok as Gaarnsmuck anplant'. Dat warrt woll ok seggt, Appels konnen gesund maken.

De Huusappel is en summergrönen Boom. Wenn he free steiht, kann he en Kroon vun 8-15 m Hööchde hebben. Siene Twiege reckt he wiet ut. Man dat is man roor, dat en Boom so groot wassen kann, vunwegen dat he up en Unnerlaag paat' is. Bovento warrt de Boom faken ok torecht sneden. De Blöer stoht in'n Wessel un hefft de Form vun en Ei oder en Ellipse. Meist sünd se utsaagt, hen un wenn hefft se en glatten Rand. Af un to gifft dat ok Lappen an'n Blattrand.

Den Huusappel sien Holt is to verglieken mit den Holtappel sien Holt. Dat Splintholt is hellroot, de Karn is rootbruun. Dat Holt is hart un swaar un warrt to de inheemschen Eddelhölter torekent. De besten Stücke levert de unbannigen Stämm vun de Mostappelböme.

De Blöten stoht alleen for sik oder in Schirmblöten. De Blötenblöer stoht in’n Krink um en Ass umto, se hefft meist de Form vun en platten Beker un sünd in’n Dörmeter 2 bit 5 cm groot. Se rüükt faken goot. De fiev grönen Kelkblöer sünd ok noch an de Früchte to finnen. De fiev Kroonblöer stoht free und sünd witt, rosa oder root. In jede Blöte gifft dat allerhand (15 bit 50) Stoffblöer, mit witte Stofffadens un gele Stoffbüdels. De Fruchtknutten, de unnen ansitten deit, besteiht ut dree bit fiev Fruchtblöer. De dree bit fiev Greepe sünd man blot ganz unnen tosamen wussen. Dat gifft ok Tucht-Sorten, dor sünd de Blöten halv oder ganz füllt. Dor sünd de Stoffblöer denn in Blötenblöer ummuddelt wurrn, de utseht, as Kroonblöer.

De Appel blöht in'n Mai un Juni. Wenn de Appels anfangt to bleihn, denn geiht dat na de Phänologie mit dat Vullvörjohr los. Wenn jummers upschreven warrt, wonnehr dat mit de Appelblöte an en Oort losgeiht, denn kann en dor wat over rutkriegen, wie sik dat Klima ännern deit, wat ganz allgemeen ja al bekannt is.[1] De Appelblöte is en typische Immenblöte.

Dat Fruchtfleesch wasst nich ut den Fruchtknotten, man ut de Blötenass. In de Biologie warrt vundeswegen vun Schienfrüchte snackt. De Appelfrucht is en sunnerliche Form vun de Sammelhuutfrücht. En Huutfrucht besteiht ut en Fruchtblatt, dat mit sik sülms tohopenwassen deit. Binnen dat Fruchtfleesch warrt ut dat huutardige Fruchtblatt en Kabuus, dat as Pergament utsehn deit. De Saat is bruun oder swatt. Dor sitt en lütt beten vun giftige Cyanide in.

Na de Aarnt riept de Appels noch na. Se tellt dor to de Klimakteerschen Frücht mit to. Wenn een bi en Banaan un annere Frücht en Appel bileggt un de Frücht todeckt, denn weert se gauer riep. Dat liggt an dat gashaftige Plantenhormon Ethen, dat bi dat Nariepen free sett warrt.

Wenn se Pellen dat Fruchtfleesch nichs chulen deit, denn warrt dat bruun (Enzymaatsch Bruunweern). Je nadem, wat for'n Soort dat is, duert dat unnerscheedlich lang. For de Gesundheit schaadt dat nich.

Wenn een Appels roh eten deit, möögt de meisten Minschen dat Kabuus nich mit eten. Faken warrt seggt, Appels schollen nich ganz vertehrt weern, vunwegen datt in'n Karn Blausüür insitten dö. Man dor hannelt sik dat blot um so'n lütt beten bi, dat een unbedenklich ok den ganzen Appel vertehren kann.

De Huusappel is dör Tucht tostanne kamen. An un for sik weer annahmen wurrn, dat he krüüzt wurrn is twuschen den Holtappel (Malus sylvestris), de ok hüdigendags noch wild wassen deit, un Malus praecox un/oder Malus dasyphylia. Man mit Hölp vun nee gentechnische Unnersöken is rutkamen, dat de Huusappel afstammen deit vun den Asiaatschen Wildappel (Malus sieversii), un dat dor denn de Kaukasusappel (Malus orientalis) inkrüüzt wurrn weer. Ok de dree annern Wildappelsorten, de boven nömmt wurrn sünd, sünd wohrschienlich tämlich fröh al inkrüüzt wurrn. Dat sütt so ut, as wenn de Huusappel an un for sik ut Asien stammen dö. Wie un wonnehr he na Middeleuropa kamen is, weet numms. Wohrschienlich hett he sik langs de olen Hannelsstraten utbreedt.

In'n Döörsnitt besteiht de Frucht vun den Huusappel to 85 % ut Water. Dat Aroma vun en Appel is tohopensett ut allerhand Stoffe. Je nadem, um wat for'n Appelsoort sik dat hanneln deit, sund düsse Stoffe in de Frucht ganz unnerscheedlich verdeelt. En Rull bi dat Appelaroma speelt sunnerlich Ester, Aldehyde un Alkohole. To de wichtigsten Esters weert Ethyl-2-methylbutyrat, Ethylbutyrat, 2-Methylbutylacetat, Butylacetat un Hexylacetat to rekent. Aldehyde kaamt to'n Deel eerst bi'n Bieten un Kauen in den Mund tostanne, wenn Fettsüren vun Enzyme ganz fix umwannelt weert. Se weert ok Gröönsmack nömmt, vunwegen, dat se na gröne Appels smecken doot, as de Granny Smith een is. To düsse Aldehyde höört Hexanal un 2-Hexanal. Bi de Alkohole sünd 1-Butanol, 2-Methylbutanol, 1-Hexanol un 2-Hexenol wichtig. Annere Aromastoffe, de for den Appel en grote Rull speelt, sünd β-Damascenon un α-Farnesen.

Dat Appelaroma hangt stark af vun de Appelsoort, vun dat Klima, vun de Tied, wenn se pluckt wurrn sünd, un ok vun de Lagertied. Toeerst in de fröhe Riepetied na de Aarnt kann een meist keen Ester in de Appels finnen. Wenn dat Aaft länger lagern deit, kann de Andeel vun Ester to'n Deel unbannig in'e Hööchd kladdern. Dat hangt vun de Soort af. So kummt mit de Tied bi dat Nariepen en anner Aroma tostanne. Man blot, wenn dat nich to veel is, finnt een dat smackhaft un schöön, anners warrt de Appel aflehnt. De is denn overriep oder overhen. Dat Nariepen kann avers afstoppt weern un wat suutjer vor sik gohn, wenn de Appels unner Kuntrull un küll holen weert. Dor is dat denn mööglich, Appels bit hen to een Johr to lagern un noch to verkopen.

Der Kulturapfel hat im Obstbau überragende Bedeutung. Das liegt daran, dass er von allen heimischen Obstarten am vielfältigsten verwendbar ist. Es gibt vom Apfel daher die weitaus meisten Zuchtformen, er gilt in unseren Breiten als das „Obst“ schlechthin.

De öllste Sort vun den Kulturappel is wohrschienlich de Borsdorper Appel, de al 1170 vun de Zisterziensers nömmt wurrn is. Um 1880 rüm hett dat in de ganze Welt al mehr as 20.000 Appelsorten geven. Alleen in Preußen weern dat mehr as 2.300 Sorten. All sünd se vun Minschen tücht' wurrn. Hüdigendags gifft dat in Düütschland um un bi 1.500 Sorten. Man vun de speelt blot 60 weertschopplich en Rull. De Sortenkunn, de veel Arbeit maken deit, un dat Plegen vun ole Arden, de nich mehr vun de Aaftindustrie anboot weert, warrt hüdigendags vun allerhand Vereene bedreven.

In'n Goornhannel un bi de Direktvermarkters sünd upstunns man blot noch 30 bit 40 Sorten to kriegen - un dat weert jummers minner. In de Supermärkte gifft dat amenne blot noch 5 bit 6 Sorten, de in de ganze Welt to kriegen sünd. In use Dage warrt ok vun Markenappels snackt. Dat sünd so nömmte Clubsorten, de blot man in Lizenz verkofft weern dröfft. So en Soort is unner annern de 'Pink Lady'. De verscheden Appelsorten weert unnerdeelt in Summerappels, Harfstappels un Winterappels.

Al fröh in ehre Kultur hefft de Minschen lehrt, nich blot Appels as Nehrmiddel to bruken, de se tofällig funnen hefft, man en Appelboom to plegen un so an Appels ran to kamen. Dat kann angohn, dat Minschen dat al doon hefft, as de Ackerbo noch gor nich begäng weer: So en Pleeg vun Appelböme is ok mööglich, wenn de Minsch noch nich duerhaftig an een Oort leven deit.

De Appel-Bueree, so, as wi de hüdigendags kennen doot, hefft in Middeleuropa de Römers inföhrt. So, as dat utsütt, sünd se bigohn un hefft anfungen, Appels to tüchten. Se hefft ok dat Upproppen un Klonen anfungen. Vun dat 6. Johrhunnert af an is de Appel in Middeleuropa anboot wurrn. Vun dat 16. Johrhunnert af an hett he in de Weertschop en Rull speelt. In Düütschland hett de Aaftpionier Otto Schmitz-Hübsch 1896 de eerste Appelplantage anleggt. To desülvige Tied hett he ok inföhrt, de Nedderstamm-Böme dune bi'nanner to planten.

De Appelböme wasst an'n besten up Grund, de goot Water dörlaten deit, man jummers fochtig holen warrt un matig veel Nehrstoffe hett. Se möögt geern in'e Sunne stohn oder in'n halven Schadden. Appels könnt Frost verdregen.

Dat is man ganz roor, wenn de Kiemlinge, de ut Appelkarns tagen sünd, sortenrein sünd. For de Tucht un dat Bi'nannerholen vun de Appelsorten sünd vundeswegen blot man de verscheden Techniken vun de Vergetative Vermehren to bruken. Dor warrt up en Unnerlage en eenjöhrigen Twieg vun de Eddelsoort paat'. De Unnerlage is dor blot man tostännig for, dat de Wuddel un de Stamm goot wassen doot. An den Eddeltwieg wasst later de Kroon mit de Appels, wo dat up afsehn is. Fröher sünd for de Unnerlagen Kiemlinge nahmen wurrn, de ut Karns tagen wurrn weern, man hüdigendags weert se dor up hentücht, dat se for de Aaftbueree goot to bruken sünd. Ut Unnerlagen, de ut Karns tagen sünd, wasst dannige Wuddeln un Kronen un se dreegt eerst na 8 bit 10 Johre de eersten Frücht. Bi Appelböme, de for sik stoht (un nich in'e Plantagen) un bi histoorsche Streiaaftanlagen sünd so'n Unnerlagen noch to finnen. De „modernen“ Unnerlagen for de Aaftbueree sünd man wat spiddelig mit minn Holt un siede Wuddeln. Se mütt jummers afstütt weern un hefft ok nödig, dat se jummers wedder Water kriegt. Man al na en poor Johre dreegt se Frucht, so, as dat wünscht is.

De Huusappel (Malus domestica, Borkh.; Pyrus malus, L.) is en Aart ut dat Geslecht vun de Appels. Se is wiethen bekannt un höört to de Familie vun de Rosenplanten (Rosaceae) mit to. Dor hannelt sik dat um en Aart vun Aaft bi, de in den Landbo weertschopplich en grote Rull speelt. De Frucht vun den Boom heet Appel. Huusappels weert to'n Eten in de Aaftbueree un ok as Gaarnsmuck anplant'. Dat warrt woll ok seggt, Appels konnen gesund maken.

Dr Kulturöpfel (Malus domestica Borkh., Syn. Pyrus malus L.) umgangssproochlig Öpfel, isch en Art us dr Gattig vo de Öpfel in dr Familie vo de Roosegwäggs (Rosaceae) und isch wit bekannt. Dr Frucht vom Öpfelbaum, wo botanisch gsee äigetlig e Schiinfrucht isch, säit mä Öpfel, und si isch wirtschaftlig e seer bedütendi Obstart.

Öpfelböim wärde as Naarigsmiddel im Obstaabau und au as Zierpflanze aapflanzt.

Dr Kulturöpfel stammt woorschinlig us Asie. Mä dänngt hüte ass er vom Asiatische Wildöpfel (Malus sieversii) chunnt, wo mit em Kaukasusöpfel (Malus orientalis) krüzt worde isch.

Öpfel wärde as Obst ooni Verarbäitig gässe, vili Sorte chönne e langi Zit glaageret wärde und si doorum in dr Vergangehäit au im Winter e wichdigi Kwelle für Witamin gsi. Si chönne, je noch Sorte, kocht und bacht wärde, oder vermostet und as Most oder Öpfelwii drunke wärde. Usserdäm wird ene e Wirkig as Häilmiddel zuegschriibe. As d Frucht schlächthii sümbolisiere dr Öpfel und dr Öpfelbaum d Themeberiich vo dr Sexualidäät, dr Fruchtbarkäit und vom Lääbe, Erkenntnis, Entschäidig, aber au Riichdum.

Dr Kulturöpfel (Malus domestica Borkh., Syn. Pyrus malus L.) umgangssproochlig Öpfel, isch en Art us dr Gattig vo de Öpfel in dr Familie vo de Roosegwäggs (Rosaceae) und isch wit bekannt. Dr Frucht vom Öpfelbaum, wo botanisch gsee äigetlig e Schiinfrucht isch, säit mä Öpfel, und si isch wirtschaftlig e seer bedütendi Obstart.

Öpfelböim wärde as Naarigsmiddel im Obstaabau und au as Zierpflanze aapflanzt.

Dr Kulturöpfel stammt woorschinlig us Asie. Mä dänngt hüte ass er vom Asiatische Wildöpfel (Malus sieversii) chunnt, wo mit em Kaukasusöpfel (Malus orientalis) krüzt worde isch.

Malus domestica esse un taxon.

Nomine commun: Malo

Secun Wikidata es un

Malus domestica esse un taxon.

Malus pumila es un specie de Malus.

Iste action ha essite automaticamente identificate como damnose, e per consequente es prohibite. Si tu crede que tu action esseva constructive, per favor informa un administrator de lo que tu tentava facer. Un breve description del regula anti-abuso correspondente a tu action es: Iste articulo es troppo curte. Per favor, adde alcun phrases.

Mansana icha T'iyu (Malus domestica) nisqaqa huk wayuq mallkim. Rurunkunatam (mansanakunata) mikhunchik.

Mansana icha T'iyu (Malus domestica) nisqaqa huk wayuq mallkim. Rurunkunatam (mansanakunata) mikhunchik.

Ing mansanas, apple keng English, metung yang pomaceous a bunga ning pun dutung a mansanas, species Malus domestica na ning familia rosas a Rosaceae. Iti ing peka gagambulan dang mumungang pun dutung.

Ing tanaman menibatan ya king Kalibudtarang Asia, nung nu ing kayang pipumpunan mayayakit ya pa angga ngeni. Atin maigit a 7,500 balu rang magagambul a mansanas a papalual a aliwaliwang uri ra. [2]

Ing mansanas, apple keng English, metung yang pomaceous a bunga ning pun dutung a mansanas, species Malus domestica na ning familia rosas a Rosaceae. Iti ing peka gagambulan dang mumungang pun dutung.

Ing tanaman menibatan ya king Kalibudtarang Asia, nung nu ing kayang pipumpunan mayayakit ya pa angga ngeni. Atin maigit a 7,500 balu rang magagambul a mansanas a papalual a aliwaliwang uri ra.

Manzanacuahuitl[1] īxōchicual ca in manzana.

Manzanacuahuitl īxōchicual ca in manzana.

Gl mir, pl. mela (Malus domestica, Borkh. 1760) è na chianda a frutt ë la famiglia ë lë Rosaceae. È una ë lë chiand da frutt cchiù chëltëvat.

Gl mir è n’álbërë pëccërigl, spëgliuand ë 5–12 m ávëtë, chë na ciuffa fota e spasa e rádëchë chë zë tròvanë ngima ngima.

Lë frunn suó altèrn e sémblëcë, a pággëna ëval, sëcat lep lep, chë na ponda pëzzuta e na bbas attënnata, ë 5–12 cm ë luongh e 3–6 cm ë larië, pëlat a part ngíma e chë na ndicchia ë pëlama a part pë sott. Gl përnucc è luongh 2–5 cm.

Gl sciuor suó ërmafrëdit ë chëlor gghiangh-rësat fòr fòr e gghiangh pëddend, a simmëtría pëndámëra. Tiev na cròlla chëmbòšta da 5 pètalë e suó larië 2,5-3,5 cm e ëvarië ínfërë. Suó rëštritt a nfiurëscènz a curimm, a númmërë ë 3-7. La scërita zë fa a la primavera. La mbëllënazion è fatta da gl nzètt.

Gl frutt (chë zë chiama a la štessa manèra ë la chianda: mir, pl. mela) zë forma pëbbía ë l’abbëttatura ë gl rëcëttáculë scëral anziema a gl ëvarië e pëcciò è në fávësë frutt; è tunn, ruoss da 5 a 9 cm ë diámmëtrë, apprima verd e quann è fatt tè në chëlor chë cagn da lë ggiall-verd a lë rusc. Gl ver frutt, chë në vè da la créscëta ë gl ëvarië, è mmèc gl turz che è cchiù tuošt a par a la carn. Gl prëcarp tè 5 carpèllëra dëspòšt comm a na štella a cingh pond; ogn carpiegl tè da un a tre sëmènd.

Gl mir è accuot da cchiù mmalatíë pë còlpa ë fugn, tra gl qual la Venturia inaequalis, la cénnërë, la monilios, gl cánghr ë lë pumacëë e la nfracëratura ë lë rádëchë.

Tra gl nzètt, gl cchiù famus suó Quadraspidiotus perniciosus, Dysaphis plantaginea e gl lëpidòttërë Cydia pomonella, Orgyia antiqua e Cossus cossus.

Gl mir, pl. mela (Malus domestica, Borkh. 1760) è na chianda a frutt ë la famiglia ë lë Rosaceae. È una ë lë chiand da frutt cchiù chëltëvat.