en

names in breadcrumbs

Hexanchus griseus are believed to have few forms of communication, as they seem to be solitary animals for the most part. Yet any social forms of communication that do exist between these animals are unknown. The only known form of communication to occur in H. griseus is during mating. The males are believed to use their teeth to entice the females into mating. These sharks are equipped with highly sensitive scent and visual organs, which are useful for perceiving the dark environment they live in. H. griseus is also able to detect other organisms by means of its lateral line system (used for detecting vibrations), and its ampullae of Lorenzini (which detect faint electric signals).

Communication Channels: visual ; tactile

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; vibrations ; chemical ; electric

Hexanchus griseus has no known evolved anti-predator adaptations. These sharks, however, are equipped with very sensitive perception organs, which may allow them to detect potential predators. The retinas are comprised of mostly rods and, therefore, do not function well in even moderately lit areas but are well suited for the dark conditions of the deep oceans. Being such a large-bodied shark, its only real predators would be other big sharks, such as whites, or possibly orca whales, which are known to prey on adult sharks. Young H. griseus have been taken by sharks, whales, dolphins, and sea lions.

Known Predators:

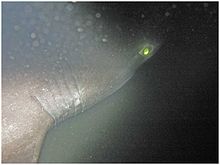

Hexanchus griseus is characteristically a large shark species with a heavy build. These sharks have a short, blunt snout, a broadly rounded mouth, and six pairs of gill slits (from which its common name, the bluntnose sixgill, is derived). They have large, green eyes and broad comb-like teeth on each side of the lower jaw arranged in 6 rows. Their coloring shades varies from grayish-black to chocolate brown on the dorsal surface and lightens to grayish-white on its belly. There is an anal fin, and one dorsal fin located on the back end of the body. The caudal fin is slightly raised so that the lower lobe is lined up with the body axis. The pelvic fins are located to the anterior of the anal fin and are a bit larger. Like many benthic sharks, the caudal fin of Hexanchus griseus has a weakly developed lower lobe. However, the bluntnose sixgill shark is still a very strong swimmer.

There exist size differences between male and female sharks. Females tend to be slightly larger than males, averaging around 4.3 m in length while males tend to stay near 3.4 m. There is little or no color difference between the sexes; however, the seasonal scars appearing on the fins of females, which are believed to be a result of mating, are commonly used for sex identification. Sex can be easily determined by the presence of elongate claspers on the pelvic fins of male sharks. The bluntnose sixgilled shark is classified under the genus Hexanchus with only one other species, Hexanchus nakamurai, or the bigeyed sixgill shark. Both sharks are similar in all aspects aside from their unmistakable size difference. While H. nakamurai reaches only about 2.3 m in length, H. griseus reaches lengths of 4.8 m.

Range mass: 480 to 720 kg.

Average mass: 500 kg.

Range length: 3.5 to 4.8 m.

Average length: 3.7 m.

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; heterothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: female larger

There is little information available about the lifespan of Hexanchus griseus. These sharks have a life expectancy no longer than 80 years in the wild. There is some suggestion that because they have such high infant birth rates, mortality rates could be very high as well. There is no known record for the oldest bluntnose sixgill shark in the wild, and this species has not been excessively studied or maintained in captivity, so there is no information on its lifespan in captivity. A new study is available, however, regarding the age determination of H. griseus. Previous techniques used in determining the age of H. griseus have been unsuccessful because of its poorly calcified vertebral centra (a characteristic of deep-water species and of primative families). This new study indicates that examining the neural arches on the fins of H. griseus can be useful in determining the age of this particular shark.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: about 80 years.

Hexanchus griseus is mainly a deep water shark, rarely found at depths of less than 100 m. The species seems to usually stay close to the bottom, near rocky reefs or soft sediments. The deepest one has been found was about 2500 m.

These sharks are diel vertical migrators; they are nocturnal and remain in the deep oceans during the day but rise towards the surface at night. Hexanchus griseus also seasonally migrates to shallower coastal waters. During the warmer months of the year, these sharks can occasionally be found in shallower waters at depths of 23 to 39 m during the day and as shallow as 3 m at night.

Range depth: 3 to 2,500 m.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; tropical ; saltwater or marine

Aquatic Biomes: benthic ; coastal

Hexanchus griseus occur globally in all oceans. These sharks live and thrive in the most widespread distribution of all known sharks, with the possible exception of white sharks.

Biogeographic Regions: indian ocean; atlantic ocean ; pacific ocean ; mediterranean sea

Other Geographic Terms: cosmopolitan

Hexanchus griseus is a skilled predator and is solely carnivorous, feeding on such animals as fishes, rays, and other sharks. Although they have been reported as being sluggish in nature, their body structure enables them to reach remarkable speeds for chasing and effectively capturing prey. Aside from feeding on molluscs and marine mammals, they eat crustaceans (crabs and shrimp), agnathans (Hagfish and sea lampreys), chondrichthyans (ratfish) and teleosts (dolphinfish and lingcod). A subspecies of H. griseus living in Cuban waters is also a skilled scavenger that feeds on carcasses of mammals.

Animal Foods: mammals; fish; carrion ; mollusks; aquatic crustaceans

Primary Diet: carnivore (Piscivore , Eats non-insect arthropods, Molluscivore )

This species is a large, deep-water predator, but we have little information on its ecological effects. There is some evidence that Hexanchus griseus has an important impact on the white sharks' population off the coast of South Africa. Researchers there believe that H. griseus will eventually outcompete Carcharodon carcharias in that area. H. griseus is not known to participate in any symbiotic relationships.

This species is killed for food, harvested with line gear, gill nets, and other equipment. It is also caught by game fishermen.

Since they are large and widespread animals, these sharkes they may have a significant role in deep-water fisheries, but we have no information on this.

Positive Impacts: food

Despite their size, these sharks are not considered much of a direct threat to humans. They are described as shy, nonagressive animals that pose no threat to humans unless physically provoked. Also, their preference for deep water and darkness makes human encounters with this species relatively rare.

Some medical professionals consider the liver of Hexanchus griseus to be toxic, as its ingestion has been known to cause painful sickness for up to 10 days. The skin of H. griseus has also been known to cause such sickness.

Little is yet known about the life cycle and fetal development of Hexanchus griseus.

Fishermen are killing H. griseus for sport and for food (as they are being more frequently spotted in fishing areas) faster than ever before. Because of their low reproductive rate, sixgill sharks can easily be over-harvested. There are new regulations being enacted prohibiting the recreational killing of these sharks. The IUCN rates this species as "Lower Risk/Near Threatened", and notes that the lack of population data means that this species could be in more trouble than we know.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: near threatened

Hexanchus griseus are mainly deepwater sharks with shy demeanors. Opportunities to study live specimens are few and far between. Bluntnose sixgill sharks kept in captivity suffer from stress due to their light-sensitive eyes and their large size.

Very little is known about these sharks in terms of their social behavior and thus little is known about their mating systems. There are a few theories, however, attempting to explain how H. griseus mates. Researchers believe that the morphology of the teeth of H. griseus play an important role in mating. The male has a more erect primary cusp than do the females. The male is believed to nip the female's gills with this cusp in order to catch her attention and entice her into mating. Evidence supporting this idea of courtship is evident by the seasonal scars that appear on females every year presumably from being nipped by males. Bluntnose sixgill sharks are believed to be primarily solitary animals and there is no information indicating whether they prefer one or many mates.

There is not much information pertaining to the reproductive behavior of Hexanchus griseus; however, there is some hypothetical information available. These sharks are believed to meet seasonally, moving to shallower depths in the May to November months. Scientists are unsure of the bluntnose sixgill shark's gestation period, but it is thought to be longer than 2 years. The means of reproduction for these sharks is ovoviviparity, meaning they carry their eggs internally until they hatch. Babies develop within the mother without a placenta to provide nourishment, and they are born at a fairly mature size (generally 70 cm at birth). Each litter can number from about 22 to 108 pups and this incredibly large litter size for H. griseus could suggest that mortality rates for the pups are very high. Little is known about their maturation because until recently determining their age was difficult as a result of their poorly calcified vertebrae. The pups of H. griseus, however, are speculated to mature around 11 to 14 years for males and 18 to 35 years for females. Little else is known about its reproductive system.

Breeding season: May - November.

Range number of offspring: 22 to 108.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 18 to 35 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 11 to 14 years.

Key Reproductive Features: seasonal breeding ; sexual ; fertilization (Internal ); ovoviviparous

There is no information available pertaining to parental care for Hexanchus griseus. However, as with other sharks, it can be assumed that no parental care is given to the young, which can number up to 108.

Parental Investment: pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female)

The bluntnose sixgill shark (Hexanchus griseus), often simply called the cow shark, is the largest hexanchoid shark, growing to 20 ft (6.1 m) in length.[2] It is found in tropical and temperate waters worldwide and its diet is widely varied by region.

The bluntnose sixgill is a species of sixgill sharks, of genus Hexanchus, a genus that also consists of two other species: the bigeye sixgill shark (Hexanchus nakamurai) and the Atlantic sixgill shark (Hexanchus vitulus). Through their base pairs of mitochondrial genes COI and ND2, these three species of sixgills widely differ from one another.[3]

The first scientific description of the bluntnose sixgill shark was authored in 1788 by Pierre Joseph Bonnaterre. As a member of the family Hexanchidae, it has more close relatives in the fossil record than living relatives. The related living species include the dogfish, the Greenland shark, and other six- and seven-gilled sharks. Some of the shark's relatives date back 200 million years. This shark is a notable species due to both its primitive and current physical characteristics.

The bluntnose sixgill shark has a large body and long tail. The snout is blunt and wide, and its eyes are small. There are 6 rows of saw-like teeth on its lower jaw and smaller teeth on its upper jaw.[4] Skin color ranges from tan, through brown, to black. It has a light-colored lateral line down the sides and on the fins' edges, and darker colored spots on the sides. They also get stains/spots on their neural arches, and the number of stains increase as they get older.[5] Its pupils are black and its eye color is a fluorescent blue-green. The bluntnose sixgill shark can grow to 5.5 m (18 ft),.[6] A work from the 1880s stated that a bluntnose sixgill shark caught off Portugal in 1846 measured 8 m (26 ft). This specimen was originally reported in an 1846 work and said to be only 0.68 m (2.2 ft) long.[7] Adult males generally average between 3.1 and 3.3 m (10 and 11 ft), while adult females average between 3.5 and 4.2 m (11 and 14 ft). The average weight of an adult bluntnose sixgill shark is 500 kilograms (1,100 pounds). Large specimens may reach 6 m (20 ft) in length and 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) in weight.[8]

The bluntnose sixgill shark resembles many of the fossil sharks from the Triassic period. A greater number of Hexanchus relatives occur in the fossil record than are alive today. They have one dorsal fin located near the caudal fin. The pectoral fins are broad, with rounded edges. The six gill slits give the shark its name. Most common sharks today only have five gill slits.

In general, the size (in length and weight) of the sixgills increase with maturity. With the male sharks specifically, their sexual maturity is usually determined by the length of their claspers. While juveniles have short and flexible ones, mature male sixgills have rigid, calcified longer ones.[9] On the other hand, the length-weight relationship of females tend to increase very rapidly as they get to the onset of their sexual maturity.[10]

With a global distribution in tropical and temperate waters, the bluntnose sixgill shark is found in a latitudinal range between 65°N and 48°S in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans.[11] It has been seen off the coasts of North and South America from North Carolina to Argentina and Alaska to Chile. In the eastern Atlantic, it has been caught from Iceland to Namibia, in the Indo-Pacific it has been caught from Madagascar north to Japan and east to Hawaii[12] and in the Mediterranean it has been caught in Greece and Malta.[13] Fossilized remains of this species from the Miocene epoch have also been discovered in South Korea.[14] It typically swims near the ocean floor or in the water column over the continental shelf in poorly lit waters.[4] It is usually found 180–1,100 m (590–3,610 ft) from the surface, inhabiting the outer continental shelf, but its depth range can extend from 0–2,500 m (0–8,202 ft).[12][15][16] Juveniles will swim near the shoreline in search of food, sometimes in water as shallow as 12 m (39 ft), but adults typically stay at depths greater than 100 m (330 ft). It can be seen near the ocean's surface only at night.[4]

An adult bluntnose sixgill shark was recently seen at a depth of 259 m (850 ft) in the Philippines. On December 2, 2017, the ROV camera of Paul Allen's research vessel RV Petrel captured video footage of the shark lurking around a World War II shipwreck in Ormoc Bay. This was the first time the species was photographed in Philippine waters.[17] In 2018, a sixgill shark was filmed near the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago, midway between Brazil and Africa, at a depth of around 120 metres (400 ft).[18] In 2019, the remains of a pregnant bluntnose sixgill shark were found on a Vancouver Island beach, north of Victoria, British Columbia.[19] On 18 October 2019, a large bluntnose sixgill shark measuring over 3 metres (9.8 ft) and weighing 900 kilograms (2,000 lb) was found dead on the beach at Urkmez beach in Seferihisar, Izmir, Turkey.

Being in such a deep area of the ocean, these sharks have developed the behavior of undergoing diel vertical migration (DVM) in order to have more access to food. Research has found that it takes more time for the sixgills to have to swim back down to their natural habitat of the bathypelagic rather than to swim up during the night to find food in the more populated zones. As such, it can be inferred that they have some sort of adaptation that aids buoyancy to ensure that these sharks are able to float more easily.[20] An example of this DVM occurrence was found off the coast of Oahu, Hawaii, whereby 4 sixgills' behaviors were studied. At around midnight to 3–am, the 4 sharks swam up to a minimum depth of 300 m (980 ft) whereas at about noon, they reached their maximum depth of between 600 and 700 m (2,000 and 2,300 ft).[21] This shows a daily pattern whereby the sixgills are going up during the nights when it is darker and colder to forage for food up in the shallower depths but as morning comes and light and higher temperatures starts to come in more intently again, the sharks go back down to their original habitat to maintain a lower metabolic rate, ensuring that they will be able to use the nutrients from whatever they ate during the night slowly, reducing the need for them to search for more food throughout the day. Another study found that the motivating factor for the bluntnose sixgill sharks' DVM behavior was foraging. Researchers were able to rule out predator and competitor avoidance as potential reasons for the vertical movement patterns because they found pairs of sharks with synchronized movements, indicating that the sharks were responding to the same stimuli. The sharks demonstrated distinct and consistent patterns of vertical migration despite size, sex, and spatial scales, showing that foraging behavior can most likely be seen as the reason for the diel vertical patterns of sixgill sharks.[22] Lastly, the bluntnose sixgill shark has consistent seasonal movements. They move north during the winter and spring and south during the summer and fall. In this study as well, researchers were able to determine that these movement patterns can be attributed to the seasonal movements of prey over other reasons.[23]

Sixgill sharks possess variability in their feeding mechanisms that could have contributed to their evolutionary success and global distribution. These sharks are able to protrude their jaws and vary their methods of feeding depending on the situation. They utilize sawing and lateral tearing techniques to manipulate food. Sixgill sharks also lower their pectoral fins right before they strike in order to stop forward progressions, making it easier for them to forage.[24]

Although sluggish in nature, the bluntnose sixgill shark is capable of attaining high speeds for chasing and catching its prey using its powerful tail. Because of its broad range, it has a wide variety of prey, including fish, rays, chimaeras, squid, crabs, shrimps, seals, and other (smaller) sharks.[12] The bluntnose sixgill shark is therefore classified as a generalist species, and is less likely to be affected by scarcity in any one of its food sources.[25] A study done in 1986, with 28 sixgills, discovered that the most abundant meal they were able to obtain include cartilaginous and bony fishes, followed by marine mammals and several invertebrates.[26] As time passes, however, it seems that their stomach contents have changed. In 1994, it was found that of 137 samples, the major prey groups were cephalopods, teleost fishes, chondrichthyans and marine mammals.[27] This difference in results could be due to several reasons. Firstly, as noticed in the different sample sizes of the two studies, it could be due to technology back then not being advanced enough to fully study the stomach contents and capture enough samples, leading to a skewed result for the 1986 study. Next, as human activities have increased over the years, it could affect the availability of food for the sixgills in the deep. There are other potential reasons for this change in diet, many factors may have affected the sixgills.

Bluntnose sixgill sharks are also positively buoyant as hypothesized earlier. During vertical movements, the sixgill sharks demonstrate more swimming efforts for the descent than the ascent. This is indicated by the greater number of tail beats and the sharks' ability to glide upwards for several minutes. The positive buoyancy can help the sharks to hunt stealthily by approaching prey from below undetected since the upward gliding permits minimal movement. It can also be advantageous for their diel vertical migrations. Since the sharks spend their days in colder water, their metabolic rates decline. Positive buoyancy can help them to glide upwards with minimal swimming involved during their evening migrations.[28]

Reproduction is ovoviviparous with embryos receiving nourishment from a yolk sac while remaining inside the mother. Litters are large and typically have 22-108 pups measuring 60–75 cm (24–30 in) at birth,[12] and the largest recorded pup is 82 centimetres (32 in). New pups are also born with a lighter belly color than adults. This form of cryptic coloration or camouflage is used to disguise the pup's appearance. A high mortality rate of the young pups is presumed, owing to the large litter size. The gestation period is unknown, but is probably more than two years, based on the gestation time of other hexanchiform sharks like the frilled sharks. Females reach sexual maturity at 4.5 m (15 ft) in length[4] and 18–35 years in age, while males reach sexual maturity much earlier at 3.15 m (10.3 ft) in size[1] and 11–14 years in age. Many biologists believe that the male bluntnose sixgill shark's teeth are specially adapted for courtship. The male nips at the female's gill slits using its longer-cusped teeth. This action is thought to entice the female into mating. Evidence of this hypothesis is that female bluntnose sixgill sharks show up with seasonal scars around their gill slits, which apparently is from breeding with males. Males and females are thought to meet seasonally between May and November.

The bluntnose sixgill shark is listed as Near Threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) because, despite its extensive range, its longevity and popularity as a sport fish makes it vulnerable to exploitation and unable to sustain targeted fishing for very long. Although population data is lacking in many areas for this species, certain regional populations have been classified as severely depleted. Although it is usually caught as bycatch, it is also caught for food and sport.[1] In June 2018, the New Zealand Department of Conservation classified the bluntnose sixgill shark as "Not Threatened" with the qualifiers "Data Poor" and "Secure Overseas" under the New Zealand Threat Classification System.[29]

This species is rather harmless to humans unless provoked.[4]

Blue Planet II, a documentary on marine organisms produced by the BBC, featured an episode focusing on deep sea organisms and environments. In this episode, bluntnose sixgill sharks were filmed feeding on a whale fall. In behind-the-scenes footage, the sharks attacked the deep sea submersible as crew members tried to collect the video footage. Thinking that they were competition, the sharks used their bodies to try to fend off the submarine, only leaving it behind once they realized that the sub was not there to feed.[30][31] The film crew was able to obtain useful video footage of the sixgills that they later featured in the episode. As a worldwide, well-known, scientific platform, it hence helped with the awareness of the existence of these species of sharks.

Since 2005, scientists have successfully been able to tag sixgill sharks as a means of studying their behavior. With this being said, however, as of 2019, there has yet to be a sixgill tagged in its natural deep-sea habitat. Researchers from Florida State University, the Florida Museum of Natural History, the Cape Eleuthera Institute, and OceanX hence decided to join forces to tag a deep-sea shark through use of a submersible, and they succeeded in doing so.[32] After 3 months of leaving the tag on the sixgill, the tag was thought to float up to the surface where scientists will be able to collect the data from that tag. Overall, this study showed how advancements in technology has helped scientists be better able to study marine life. Instead of having to go on an expedition for years at a time, the scientists here simply had to attach a tag onto the sixgill once and collect the data another time. The tag simply showed behavioral results of the sixgills.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) The bluntnose sixgill shark (Hexanchus griseus), often simply called the cow shark, is the largest hexanchoid shark, growing to 20 ft (6.1 m) in length. It is found in tropical and temperate waters worldwide and its diet is widely varied by region.

The bluntnose sixgill is a species of sixgill sharks, of genus Hexanchus, a genus that also consists of two other species: the bigeye sixgill shark (Hexanchus nakamurai) and the Atlantic sixgill shark (Hexanchus vitulus). Through their base pairs of mitochondrial genes COI and ND2, these three species of sixgills widely differ from one another.