en

names in breadcrumbs

Like minke whales, and fin whales, humpbacks are generalized feeders. They are highly mobile and opportunistic. Humpbacks feed upon plankton, the plant and animal life at the surface of the ocean's water, or upon fish in large patches or schools. Because of this, humpbacks are classified as "swallowers" and not "skimmers." They do eat commercially exploited fishes. Feeding by humpbacks takes place during the summer.

Atka makerel and Pacific saury are the most commonly found fish prey of humpbacks in the eastern North Pacific Ocean. The former is considered one of the favorite foods of humpback whales in waters off the Western Aleutians and South of the Amchitka Islands. In addition, humpbacks in the North Pacific and the Bering Sea eat euphausiids (krill), mackerel, sand lance, Ammodytes americanus, capelin and herring.

Fishes comprise about 95% of the diet of North Atlantic humpbacks. Those humpbacks living in the Atlantic Ocean, specifically near Cape Cod and Greenland, also eat sand lance, herring and pollock.

Humpbacks near Australia and in the Antartic also feed on euphausiids.

Typically, these whales take both food and water into their mouths. Large volumes can be accomodated because the ventral grooves in the throat allow for expansion. Once the mouth is full, it is closed and the water is pressed out. Meanwhile, the food is caught in the baleen plates and is then swallowed. This process is aided by the internal mechanism of rorqual feeding--the tongue.

Humpbacks have five main feeding behaviors (the first three are more commonly observed than the last two):

Bubble clouds are large inter-connected masses of bubbles formed by one underwater exhalation. Clouds concentrate or herd a mass of prey. Feeding is presumed to occur underwater. After that the humpback rises slowly to the surface within the bubble cloud. After several blows and some shallow diving, the manuever is repeated. Bubble clouds appear to assist in prey detection or capture by immobilizing or confusing prey. Bubble clouds may cause a jumping response among the prey, helping the whale to detect the prey, or it may disguise the whale from the prey.

Bubble columns are formed as a humpback swims underwater in a broad circle while exhaling. An individual column may form rows, semicircles, or complete circles. These circles act like a seive net, concentrating or herding the prey.

At times, humpbacks combine some of these methods, for example, combining bubble feeding and tail slapping (lobtailing), as they feed on sand lance.

It is important to note that no humpback younger than two years old uses the tail slapping method, although they are weaned from their mothers at one year. However, rudimentary lobtail feeding has been witnessed several times among older post-weaning young.

In addition, no difference has been noted in the frequency of lobtail feeding between the sexes.

Animal Foods: fish; zooplankton

Foraging Behavior: filter-feeding

Primary Diet: carnivore (Piscivore ); planktivore

The cerebellum of humpback whales constitutes about 20% of the total weight of the brain; the brain does not differ much from those of other mysticete whales.

The olfactory organs of humpback whales are greatly reduced and it is doubtful whether they have a sense of smell at all. Their eyes are small and adapted to withstand water pressure. Their external auditory passages are narrow, leading to a minute hole on the head not far behind the eye.

Humpback females are larger than males. They are one of the few species of mammals for which this is true.

The most distictive external features of humpbacks are the flipper size and form, fluke coloration and shape, and dorsal fin shape. Flippers are quite long and can be almost a third of the body length. They are largely white and have knobs on the leading edge. The butterfly-shaped tail flukes bear individually distinctive patterns of gray and white, and have a scalloped trailing edge. The dorsal fin can be a small triangle or sharply falcate, and often has a stepped or humped shape; this is one source of the name "humpback."

There are 14 to 35 ventral pleats or grooves.

Humpbacks have the greatest relative blubber thickness for their size of any rorqual. Megaptera novaeangliae is second only to blue whales in absolute thickness of blubber. Blubber thickness varies at different times of the year, as well as with age and physiological condition.

Baleen plates are usually all black with blackish bristles.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: female larger

Average mass: 3e+07 g.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 77.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 95.0 years.

The habitat of humpback whales consists of polar to tropical waters, including the waters of the Artic, Atlantic, and Pacific Oceans, as well as the waters surrounding Antartica and the Bering Strait. During migration, they are found in coastal and deep oceanic waters. Generally, they do not come into coastal waters until they reach the lattitudes of Long Island, New York, and Cape Cod, Massachessetts.

Humpbacks are divided into several populations. These are for the most part isolated, but with a little interchange in some cases. There are two stocks in the north Atlantic Ocean and two in the north Pacific. There are also seven isolated stocks in the southern hemisphere.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; tropical ; polar ; saltwater or marine

Aquatic Biomes: benthic ; coastal

Humpback whales, Megaptera novaeangliae, live in polar and tropical waters, particularly those of the Atlantic, Arctic, and Pacific Oceans. Their range also includes the waters of the Bering Sea and the waters surrounding Antarctica.

Biogeographic Regions: arctic ocean (Native ); atlantic ocean (Native ); pacific ocean (Native )

Humpbacks have historically had incredible economic importance to humans. They were one of the nine species hunted intensively by whalers. They were at times the most important constituent of the catch of modern whalers. Their oil was in demand as a kind of burning oil for lamps and as a lubricant for machinery. Whale oil was also used as a raw material for margarine and as a component of cooking fat. Whale meat was processed for human consumption and made into animal feed. Meal made from whale bones was used as fertilizer.

However, these animals are no longer hunted extensively. They do continue to have some economic impact, as ecotourism and whale sighting tours are quite popular in appropriate coastal areas.

Positive Impacts: ecotourism

Humpback whales staying close to the shore on the Eastern Canadian seaboard damage cod and herring traps and can tear loose long lengths of a set net.

Negative Impacts: crop pest

Currently, there are an estimated 6,000 humpbacks in the earth's waters, with possibly 1,000 to 3,000 more. The healthiest populations occur in the western north Atlantic Ocean. A few other areas in which there are small populations include the waters near Beguia, Cape Verde, Greenland, and Tonga. Global humpback populations have begun to strengthen, although this species is still a conservation concern.

Humpback whales received some protection in 1985 when the International Whaling Commission instituted a moratorium on commercial whaling. In the early part of the twentieth century, during the modern whaling era, humpback whales were highly vulnerable due to their tendency to aggregate on the tropical breeding grounds and to come close to the shore on the northern feeding grounds.

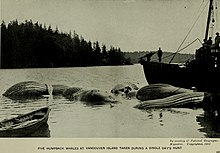

More than 60,000 humpbacks were killed between 1910 to 1916 in the southern hemisphere, and there were other peaks of exploitation in the 1930's and 1950's. In the North Pacific, there were peak catches of over 3,000 in 1962 to 1963.

In order to combat the problem of depletion, catching humpback whales was prohibited in the Antartic in 1939, although that plan was abandoned in 1949. In the southern hemisphere, hunting was banned in 1963. In the North Atlantic, hunting was banned in 1956. Finally hunting was banned in the North Pacific in 1966.

US Federal List: endangered

CITES: appendix i

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

Perception Channels: tactile ; chemical

The common name "humpback" also comes from the animal's tendency to round its back when diving.

Some humpbacks have whitish, oval-shaped scars, which are the marks of parasitic sea lampreys. Humpback whales have few predators other than humans. They are sometimes harassed, perhaps killed, by killer whales, and sharks feed on their dead bodies.

Little is known about the diseases that affect humpback whales. However, true rorquals get cirrhosis of the liver and mastitis. It is unlear as to whether humpbacks also get them.

Humpbacks are the most parasitized of all of the Balaenopteridae. They tend to carry a wide variety of ecto and endoparasites. The number of parasites may be related to the swimming speed of this species. The slow pace of humpbacks is thought to allow accumulation of parasites to occur.

Humpbacks have different types of whale lice living in their scars, scratches, chins, throats, and urogenital slits. Barnacles also live in their throats, chins, and urogenital slits.

Some endoparasites that live within the whales are trematodes, cestodes, nematodes, acanthocephalans. Helminths live in the blubber, liver, mesentery, and intestine, while Ogmogaster ceti (a commensal nematode specific to the Balaenopteridae) lives in the baleen plates.

Pollutants that have been reported from the blubber of humpbacks include DDT, PCBs, chlordane, and dieldrin. The levels of these toxins vary during the migratory pattern of the humpbacks. The levels are highest during feeding and are lowest during breeding.

Humpbacks appear to possess a polygynous/polygamous mating system, with males competing aggressively for access to oestrous females.

Mating System: polygynous

The reproductive habits of humpback whales are typically mammalian. The breeding season is during the winter, and breeding takes place in tropical waters.

There are few actual observations of copulation in this species. The male and the female first swim in a line; they then engage in rolling, flipping, and tail fluking. Next, both dive and then surface vertically, with ventral surfaces "in close contact." They emerge from the water to a point below their flippers. They then fall back onto the surface of the water together. The gestation period lasts 11 to 11.5 months. During that time the embryo grows approximately 17 to 35 cm per month.

Sexual maturity is usually reached between 4 to 5 years. In males, the length of the penis can be an indication of sexual maturity. However, in some cases, puberty may proceed sexual maturity by one year. In sexually mature males, the weight of the testes and the rate of spermatogenesis increase during the breeding season, coinciding with the ovulation of the females. In the females, after sexual maturity is reached, ovary weight remains fairly constant. As ovulation approaches, "resting" Graafian follicles on the surface of the ovaries enlarge. There generally is only one ovulation per breeding season.

Breeding usually takes place once every two years, but it may occur twice every three years. In the latter situation, lactation may last longer that 5 months.

If a female is impregnated shortly after parturition, pregnancy and lactation may proceed simultaneously.

Breeding interval: Females of this species typically produce offspring every two years, and can produce yound twice in three years.

Range number of offspring: 1 (low) .

Average number of offspring: 1.

Range gestation period: 11 to 11.5 months.

Average weaning age: 5 months.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 4 to 5 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 4 to 5 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization ; viviparous

Average birth mass: 1.35e+06 g.

Average number of offspring: 1.

Calves are born in the warm tropical waters and subtropical waters of each hemisphere. Newborns are usually 4 to 5 m long, and are suckled by their mothers for about 5 months. The females' milk is highly nutritive, containing high amounts of fat, protein, lactose and water. There is no parental investment on the part of the males.

Parental Investment: pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female)

Known for theirsongsthat travel to great distances, these massive 40 tonne mammals are one of the most easily recognised whale species.

Humpback whales have long flippers that are almost a third of theirbody size, a hump on their backs as their common name suggests and a black and white tail fluke.The variation in tail fluke coloration helps scientist to identify individuals within the family group known as a pod.

Humpbacks are a widespread species, occurring in oceans around the world.They migrate up to25 000 kmeach year.This migration is from the humpbacks feeding ground in the polar regions to tropical and subtropical waters where they give birth to their young.How?Humpback whales are powerful swimmers.Their strong tail fluke propels them through the water and help the whales to propel itself out the water – a behaviour known as breaching.

Humpback whales feed on mostly krill and small schools of fish.Humpbacks canhunt aloneby hitting the water with its pectoral fins or its tail fluke in order to stun its prey.It can also hunt by cooperating with other humpback whales using a method calledbubble net feeding.A group of whales will swim in a shrinking circle, blowing bubbles beneath a school of prey until they are confined into a concentrated column.The whales then swim upward into the net of bubbles with their mouths open and swallow many fish in one gulp.

Female humpback whales only have one calf at a time.These calves will be suckled by their mothers for approximately5 months.Mothers and calves swim close together, often touching one another with their flippers with what appear to be gestures ofaffection.

TheIUCNhas removed humpback whales from the Vulnerable species listing and currently lists these whales as a species of Least Concern.However, there is information lacking on discrete populations.

For more information on MammalMAP, visit the MammalMAPvirtual museumorblog.

The species associated with this article partially comprise the benthic community of Stellwagen Bank, an undersea gravel and sand deposit stretching between Cape Cod and Cape Ann off the coast of Massachusetts. Protected since 1993 as part of the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, the bank is known primarily for whale-watching and commercial fishing of cod, lobster, hake, and other species (Eldredge 1993).

The benthic community of Stellwagen Bank is diverse and varied, depending largely on the grain size of the substrate. Sessile organisms such as bryozoans, ascidians, tunicates, sponges, and tube worms prefer gravelly and rocky bottoms, while burrowing worms, burrowing anemones, and many mollusks prefer sand or mud surfaces (NOAA 2010). Macroalgae, such as kelps, are exceedingly rare in the area — most biogenic structure along the bottom is provided by sponges, cnidarians, and worms. The dominant phyla of the regional benthos are Annelida, Mollusca, Arthropoda, and Echinodermata (NOAA 2010).

Ecologically, the Stellwagen Bank benthos contributes a number of functions to the wider ecosystem. Biogenic structure provided by sessile benthic organisms is critical for the survivorship of juveniles of many fish species, including flounders, hake, and Atlantic cod. The benthic community includes a greater than average proportion of detritivores — many crabs and filter-feeding mollusks — recycling debris which descends from the water column above (NOAA 2010). Finally, the organisms of the sea-bed are an important source of food for many free-swimming organisms. Creatures as large as the hump-backed whale rely on the benthos for food — either catching organisms off the surface or, in the whale’s case, stirring up and feeding on organisms which burrow in sandy bottoms (Hain et al 1995).

As a U.S. National Marine Sanctuary, Stellwagen Bank is nominally protected from dredging, dumping, major external sources of pollution, and extraction of mammals, birds or reptiles (Eldredge 1993). The benthic habitat remains threatened, however, by destructive trawling practices. Trawl nets are often weighted in order that they be held against the bottom, flattening soft surfaces, destroying biogenic structure, and killing large numbers of benthic organisms. There is also occasional threat from contaminated sediments dredged from Boston harbor and deposited elsewhere in the region (NOAA 2010). The region benefits from close observation by NOAA and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, however, and NOAA did not feel the need to make any special recommendations for the preservation of benthic communities in their 2010 Management Plan and Environmental Assessment.

The humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) is a species of baleen whale. It is a rorqual (a member of the family Balaenopteridae) and is the only species in the genus Megaptera. Adults range in length from 14–17 m (46–56 ft) and weigh up to 40 metric tons (44 short tons). The humpback has a distinctive body shape, with long pectoral fins and tubercles on its head. It is known for breaching and other distinctive surface behaviors, making it popular with whale watchers. Males produce a complex song typically lasting 4 to 33 minutes.

Found in oceans and seas around the world, humpback whales typically migrate up to 16,000 km (9,900 mi) each year. They feed in polar waters and migrate to tropical or subtropical waters to breed and give birth. Their diet consists mostly of krill and small fish, and they use bubbles to catch prey. During the wintertime, they rely on their blubber storage for their energy[5]They are promiscuous breeders, with both sexes having multiple partners. Orcas are the main natural predators of humpback whales.

Like other large whales, the humpback was a target for the whaling industry. Humans once hunted the species to the brink of extinction; its population fell to around 5,000 by the 1960s. Numbers have partially recovered to some 135,000 animals worldwide, while entanglement in fishing gear, collisions with ships, and noise pollution continue to affect the species.

The humpback was first identified as baleine de la Nouvelle Angleterre by Mathurin Jacques Brisson in his Regnum Animale of 1756. In 1781, Georg Heinrich Borowski described the species, converting Brisson's name to its Latin equivalent, Balaena novaeangliae. In 1804, Bernard Germain de Lacépède shifted the humpback from the family Balaenidae, renaming it B. jubartes. In 1846, John Edward Gray created the genus Megaptera, classifying the humpback as Megaptera longipinna, but in 1932, Remington Kellogg reverted the species names to use Borowski's novaeangliae.[6] The common name is derived from the curving of their backs when diving. The generic name Megaptera from the Ancient Greek mega- μεγα ("giant") and ptera/ πτερα ("wing")[7] refer to their large front flippers. The specific name means "New Englander" and was probably given by Brisson due to regular sightings of humpbacks off the coast of New England.[6]

BalaenopteridaeB. acutorostrata/bonaerensis (minke whale species complex) ![]()

B. musculus (blue whale)![]()

B. borealis (sei whale) ![]()

Eschrichtius robustus (gray whale) ![]()

B. physalus (fin whale) ![]()

Megaptera novaeangliae (humpback whale) ![]()

Humpback whales are rorquals, members of the Balaenopteridae family, which includes the blue, fin, Bryde's, sei and minke whales. A 2018 genomic analysis estimates that rorquals diverged from other baleen whales in the late Miocene, between 10.5 and 7.5 million years ago. The humpback and fin whale were found to be sister taxon.[8] There is reference to a humpback-blue whale hybrid in the South Pacific, attributed to marine biologist Michael Poole.[9][10]

Modern humpback whale populations originated in the southern hemisphere around 880,000 years ago and colonized the northern hemisphere 200,000–50,000 years ago. A 2014 genetic study suggested that the separate populations in the North Atlantic, North Pacific, and Southern Oceans have had limited gene flow and are distinct enough to be subspecies, with the scientific names of M. n. novaeangliae, M. n. kuzira and M. n. australis respectively.[11] A non-migratory population in the Arabian sea has been isolated for 70,000 years.[12]

The adult humpback whale is generally 14–15 m (46–49 ft), though longer lengths of 16–17 m (52–56 ft) have been recorded. Females are usually 1–1.5 m (3 ft 3 in – 4 ft 11 in) longer than males.[13] The species can reach body masses of 40 metric tons (44 short tons). Calves are born at around 4.3 m (14 ft) long with a weight of 680 kg (1,500 lb).[14]

The body is bulky with a thin rostrum and proportionally long flippers, each around one-third of its body length.[15][16] It has a short dorsal fin that varies from nearly non-existent to somewhat long and curved. As a rorqual, the humpback has grooves between the tip of the lower jaw and the navel.[13] They are relatively few in number in this species, ranging from 14–35.[15] The mouth is lined with baleen plates, which number 270-400 for both sides.[16]

Unique among large whales, humpbacks have bumps or tubercles on the head and front edge of the flippers; the tail fluke has a jagged trailing edge.[13][16] The tubercles on the head are 5–10 cm (2.0–3.9 in) thick at the base and poke up to 6.5 cm (2.6 in). They are mostly hollow in the center, often containing at least one fragile hair that erupts 1–3 cm (0.39–1.18 in) from the skin and is 0.1 mm (0.0039 in) thick. The tubercles develop early in the womb and may have a sensory function as they are rich in nerves.[17]

The dorsal or upper-side of the animal is generally black; the ventral or underside has various levels of black and white coloration.[13] Whales in the southern hemisphere tend to have more white pigmentation. The flippers can vary from all-white to white only on the undersurface.[14] The varying color patterns and scars on the tail flukes distinguish individual animals.[18][19] The end of the genital slit of the female is marked by a round feature, known as the hemispherical lobe, which visually distinguishes males and females.[16][20]

Humpback whale groups, aside from mothers and calves, typically last for days or weeks at the most.[13][21] They are normally sighted in small groups though large aggregations form during feeding and among males competing for females.[21] Humpbacks may interact with other cetacean species, such as right whales, fin whales, and bottlenose dolphins.[22][23][24] Humpbacks are highly active at the surface, performing aerial behaviors such as breaching and surface slapping with the tail (lobtailing) and flippers. These may be forms of play and communication and/or for removing parasites.[13]

Humpbacks rest at the surface with their bodies laying horizontally.[25] The species is a slower swimmer than other rorquals, cruising at 7.9–15.1 km/h (4.9–9.4 mph). When threatened, a humpback may speed up to 27 km/h (17 mph).[16] They appear to dive within 150 m (490 ft) and rarely below 120 m (390 ft).[26] Dives typically do not exceed five minutes during the summer but are normally 15–20 minutes during the winter.[16] As it dives, a humpback typically raises its tail fluke, exposing the underside.[13]

Humpback whales feed from spring to fall. They are generalist feeders, their main food items being krill and small schooling fish. The most common krill species eaten in the southern hemisphere is the Antarctic krill. Further north, the northern krill and various species of Euphausia and Thysanoessa are consumed. Fish prey include herring, capelin, sand lances and Atlantic mackerel.[13][16] Like other rorquals, humpbacks are "gulp feeders", swallowing prey in bulk, while right whales and bowhead whales are skimmers.[21] The whale increases its mouth gape by expanding the grooves.[13] Water is pushed out through the baleen.[27] In the southern hemisphere, humpbacks have been recorded foraging in large compact gatherings numbering up to 200 individuals.[28]

Humpbacks hunt their prey with bubble-nets. A group of whales swim in a shrinking circle while blowing air from their blowholes, capturing the prey above them in a cylinder of bubbles. They may dive up to 20 m (66 ft) performing this technique. Bubble-netting comes in two main forms; upward spirals and double loops. Upward spirals involve the whales blowing air from their blowhole continuously as they circle towards the surface, creating a spiral of bubbles. Double loops consist of a deep, long loop of bubbles that herds the prey, followed by slapping the surface and then a smaller loop that prepares the final capture. Combinations of spiraling and looping have been recorded. After the humpbacks create the "nets", the whales swim into them with their mouths gaping and ready to swallow.[27]

Using network-based diffusion analysis, one study argued that whales learned lobtailing from other whales in the group over 27 years in response to a change in primary prey.[29][30] The tubercles on the flippers stall the angle of attack, which both maximizes lift and minimizes drag (see tubercle effect). This, along with the shape of the flippers, allows the whales to make the abrupt turns necessary during bubble-feeding.[31]

Mating and breeding take place during the winter months, which is when females reach estrus and males reach peak testosterone and sperm levels.[13] Humpback whales are promiscuous, with both sexes having multiple partners.[13][32] Males will frequently trail both lone females and cow–calf pairs. These are known as "escorts", and the male that is closest to the female is known as the "principal escort", who fights off the other suitors known as "challengers". Other males, called "secondary escorts", trail further behind and are not directly involved in the conflict.[33] Agonistic behavior between males consists of tail slashing, ramming, and head-butting.[13]

Gestation in the species lasts 11.5 months, and females reproduce every two years.[13] Humpback whale births have been rarely observed. One birth witnessed off Madagascar occurred within four minutes.[34] Mothers typically give birth in mid-winter, usually to a single calf. Calves suckle for up to a year but can eat adult food in six months. Humpbacks are sexually mature at 5–10 years, depending on the population.[13] The length at maturity is around 12.5 m (41 ft).[35][36] Humpback whales possibly live over 50 years.[14]

Male humpback whales produce complex songs during the winter breeding season. These vocals range in frequency between 100 Hz to 4 Hz, with harmonics reaching up to 24 kHz or more, and can travel at least 10 km (6.2 mi). Males may sing for between 4 and 33 minutes, depending on the region. In Hawaii, humpback whales have been recorded vocalizing for as long as 7 hours.[37] Songs are divided into layers; "subunits", "units", "subphrases", "phrases" and "themes". A subunit refers to the discontinuities or inflections of a sound while full units are individual sounds, similar to musical notes. A succession of units creates a subphrase, and a collection of subphrases make up a phrase. Similar-sounding phrases are repeated in a series grouped into themes, and multiple themes create a song.[38]

The function of these songs has been debated, but they may have multiple purposes. There is little evidence to suggest that songs establish dominance among males. However, there have been observations of non-singing males disrupting singers, possibly in aggression. Those who join singers are males who were not previously singing. Females do not appear to approach singers that are alone, but may be drawn to gatherings of singing males, much like a lek mating system. Another possibility is that songs bring in foreign whales to populate the breeding grounds.[37] It has also been suggested that humpback whale songs have echolocating properties and may serve to locate other whales.[39] A 2023 study found that as humpback whales numbers have recovered from whaling, singing has become less common.[40]

Whale songs are similar among males in a specific area. Males may alter their songs over time, and others in contact with them copy these changes.[38] They have been shown in some cases to spread "horizontally" between neighboring populations throughout successive breeding seasons.[41] In the northern hemisphere, songs change more gradually while southern hemisphere songs go through cyclical "revolutions".[42]

Humpback whales are reported to make other vocalizations. "Snorts" are quick low-frequency sounds commonly heard among animals in groups consisting of a mother–calf pair and one or more male escort groups. These likely function in mediating interactions within these groups. "Grumbles" are also low in frequency but last longer and are more often made by groups with one or more adult males. They appear to signal body size and may serve to establish social status. "Thwops" and "wops" are frequency modulated vocals, and may serve as contact calls both within and between groups. High-pitched "cries" and "violins" and modulated "shrieks" are normally heard in groups with two or more males and are associated with competition. Humpback whales produce short, low-frequency "grunts" and short, modulated "barks" when joining new groups.[43]

Visible scars indicate that orcas prey upon juvenile humpbacks.[21] A 2014 study in Western Australia observed that when available in large numbers, young humpbacks can be attacked and sometimes killed by orcas. Moreover, mothers and (possibly related) adults escort calves to deter such predation. The suggestion is that when humpbacks suffered near-extinction during the whaling era, orcas turned to other prey but are now resuming their former practice.[44] There is also evidence that humpback whales will defend against or mob killer whales who are attacking either humpback calves or juveniles as well as members of other species, including seals. The humpback's protection of other species may be unintentional, a "spillover" of mobbing behavior intended to protect members of its species. The powerful flippers of humpback whales, often infested with large, sharp barnacles, are formidable weapons against orcas. When threatened, they will thresh their flippers and tails keeping the orcas at bay.[45]

The great white shark is another confirmed predator of the humpback whale. In 2020, Marine biologists Dines and Gennari et al., published a documented incident of a group of great white sharks exhibiting pack-like behavior to attack and kill a live adult humpback whale.[46] A second incident regarding great white sharks killing humpback whales was documented off the coast of South Africa. The shark recorded instigating the attack was a female nicknamed "Helen". Working alone, the shark attacked a 33 ft (10 m) emaciated and entangled humpback whale by attacking the whale's tail to cripple and bleed the whale before she managed to drown the whale by biting onto its head and pulling it underwater.[47][48]

Humpback whales are found worldwide, except for some areas at the equator and High Arctic and some enclosed seas.[14] The furthest north they have been recorded is at 81°N around northern Franz Josef Land.[49] They are usually coastal and tend to congregate in waters within continental shelves. Their winter breeding grounds are located around the equator; their summer feeding areas are found in colder waters, including near the polar ice caps. Humpbacks go on vast migrations between their feeding and breeding areas, often crossing the open ocean. The species has been recorded traveling up to 8,000 km (5,000 mi) in one direction.[14] An isolated, non-migratory population feeds and breeds in the northern Indian Ocean, mainly in the Arabian Sea around Oman.[50] This population has also been recorded in the Gulf of Aden, the Persian Gulf, and off the coasts of Pakistan and India.[51]

In the North Atlantic, there are two separate wintering populations, one in the West Indies, from Cuba to northern Venezuela, and the other in the Cape Verde Islands and northwest Africa. During summer, West Indies humpbacks congregate off New England, eastern Canada, and western Greenland, while the Cape Verde population gathers around Iceland and Norway. There is some overlap in the summer ranges of these populations, and West Indies humpbacks have been documented feeding further east.[50] Whale visits into the Gulf of Mexico have been infrequent but have occurred in the gulf historically.[52] They were considered to be uncommon in the Mediterranean Sea, but increased sightings, including re-sightings, indicate that more whales may colonize or recolonize it in the future.[53]

The North Pacific has at least four breeding populations: off Mexico (including Baja California and the Revillagigedos Islands), Central America, the Hawaiian Islands, and both Okinawa and the Philippines. The Mexican population forages from the Aleutian Islands to California, particularly the Bering Sea, northern and western Gulf of Alaska, southern British Columbia to northern Washington State, and Oregon to California. During the summer, Central American humpbacks are found only off Oregon and California. In contrast, Hawaiian humpbacks have a wide feeding range but most travel to southeast Alaska and northern British Columbia. The wintering grounds of the Okinawa/Philippines population are mainly around the Russian Far East. There is some evidence for a fifth population somewhere in the northwestern Pacific. These whales are recorded to feed off the Aleutians with a breeding area somewhere south of the Bonin Islands.[50]

In the Southern Hemisphere, humpback whales are divided into seven breeding stocks, some of which are further divided into sub-structures. These include the southeastern Pacific (stock G), southwestern Atlantic (stock A), southeastern Atlantic (stock B), southwestern Indian Ocean (stock C), southeastern Indian Ocean (stock D), southwestern Pacific (stock E), and the Oceania stock (stocks E–F).[50] Stock G breeds in tropical and subtropical waters off the west coast of Central and South America and forages along the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, the South Orkney Islands and to a lesser extent the Tierra del Fuego of southern Chile. Stock A winters off Brazil and migrates to summer grounds around South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. Some stock A individuals have also been recorded off the western Antarctic Peninsula, suggesting an increased blurring of the boundaries between the feeding areas of stocks A and G.[54]

Stock B breeds on the west coast of Africa and is further divided into Bl and B2 subpopulations, the former ranging from the Gulf of Guinea to Angola and the latter ranging from Angola to western South Africa. Stock B whales have been recorded foraging in waters to the southwest of the continent, mainly around Bouvet Island.[55] Comparison of songs between those at Cape Lopez and Abrolhos Archipelago indicate that trans-Atlantic mixings between stock A and stock B whales occur.[56] Stock C whales winter around southeastern Africa and surrounding waters. This stock is further divided into C1, C2, C3, and C4 subpopulations; C1 occurs around Mozambique and eastern South Africa, C2 around the Comoro Islands, C3 off the southern and eastern coast of Madagascar and C4 around the Mascarene Islands. The feeding range of this population is likely between coordinates 5°W and 60°E and under 50°S.[50][55] There may be overlap in the feeding areas of stocks B and C.[55]

Stock D whales breed off the western coast of Australia, and forage in the southern region of the Kerguelen Plateau.[57] Stock E is divided into E1, E2, and E3 stocks.[50] E1 whales have a breeding range off eastern Australia and Tasmania; their main feeding range is close to Antarctica, mainly within 130°E and 170°W.[58] The Oceania stock is divided into the New Caledonia (E2), Tonga (E3), Cook Islands (F1) and French Polynesia (F2) subpopulations. This stock's feeding grounds mainly range from around the Ross Sea to the Antarctic Peninsula.[59]

Humpback whales were hunted as early as the late 16th century.[3] They were often the first species to be harvested in an area due to this coastal distribution.[13] North Pacific kills alone are estimated at 28,000 during the 20th century.[15] In the same period, over 200,000 humpbacks were taken in the Southern Hemisphere.[13] North Atlantic populations dropped to as low as 700 individuals.[15] In 1946, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) was founded to oversee the industry. They imposed hunting regulations and created hunting seasons. To prevent extinction, IWC banned commercial humpback whaling in 1966. By then, the global population had been reduced to around 5,000.[60] The Soviet Union deliberately under-recorded its catches; the Soviets reported catching 2,820 between 1947 and 1972, but the true number was over 48,000.[61]

As of 2004, hunting was restricted to a few animals each year off the Caribbean island of Bequia in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.[62] The take is not believed to threaten the local population. Japan had planned to kill 50 humpbacks in the 2007/08 season under its JARPA II research program. The announcement sparked global protests.[63] After a visit to Tokyo by the IWC chair asking the Japanese for their co-operation in sorting out the differences between pro- and anti-whaling nations on the commission, the Japanese whaling fleet agreed to take no humpback whales during the two years it would take to reach a formal agreement.[64] In 2010, the IWC authorized Greenland's native population to hunt a few humpback whales for the following three years.[65]

As of 2018, the IUCN Red List lists the humpback whale as least-concern, with a worldwide population of around 135,000 whales, of which around 84,000 are mature individuals, and an increasing population trend.[3] Prior to 2008, the IUCN listed the species as vulnerable.

[66] Regional estimates are around 13,000 in the North Atlantic, 21,000 in the North Pacific, and 80,000 in the southern hemisphere. For the isolated population in the Arabian sea, only around 80 individuals remain,[67] and this population is considered to be endangered. In most areas, humpback whale populations have recovered from historic whaling, particularly in the North Pacific.[14] Such recoveries have led to the downlisting of the species' threatened status in the United States, Canada, and Australia.[66][68] In Costa Rica, Ballena Marine National Park was established for humpback protection.[69]

Humpbacks still face various other human-made threats, including entanglement by fishing gear, vessel collisions, human-caused noise and traffic disturbance, coastal habitat destruction, and climate change.[14] Like other cetaceans, humpbacks can be injured by excessive noise. In the 19th century, two humpback whales were found dead near repeated oceanic sub-bottom blasting sites, with traumatic injuries and fractures in the ears.[70] Saxitoxin, a paralytic shellfish poisoning from contaminated mackerel, has been implicated in humpback whale deaths.[71] While oil ingestion is a risk for whales, a 2019 study found that oil did not foul baleen and instead was easily rinsed by flowing water.[72]

Whale researchers along the Atlantic Coast report that there have been more stranded whales with signs of vessel strikes and fishing gear entanglement in recent years than ever before. The NOAA recorded 88 stranded humpback whales between January 2016 and February 2019. This is more than double the number of whales stranded between 2013 and 2016. Because of the increase in stranded whales, NOAA declared an unusual mortality event in April 2017. Virginia Beach Aquarium's stranding response coordinator, Alexander Costidis, stated the conclusion that the two causes of these unusual mortality events were vessel interactions and entanglements.[73]

Much of the growth of commercial whale watching was built on the humpback whale. The species' highly active surface behaviors and tendency to become accustomed to boats have made them easy to observe, particularly for photographers. In 1975, humpback whale tours were established in New England and Hawaii.[74] This business brings in a revenue of $20 million per year for Hawaii's economy.[75] While Hawaiian tours have tended to be commercial, New England and California whale watching tours have introduced educational components.[74]

In December 1883, a male humpback swam up the Firth of Tay in Scotland, past what was then the whaling port of Dundee. Harpooned during a failed hunt, it was found dead off Stonehaven a week later. Its carcass was exhibited to the public by a local entrepreneur, John Woods, both locally and then as a touring exhibition that traveled to Edinburgh and London. The whale was dissected by Professor John Struthers, who wrote seven papers on its anatomy and an 1889 monograph on the humpback.[76][77][78][79]

An albino humpback whale that travels up and down the east coast of Australia became famous in local media because of its rare, all-white appearance. Migaloo is the only known Australian all-white specimen,[80] and is a true albino.[81] First sighted in 1991, the whale was named for an indigenous Australian word for "white fella". To prevent sightseers from approaching dangerously close, the Queensland government decreed a 500-m (1600-ft) exclusion zone around him.[82]

Migaloo was last seen in June 2014 along the coast of Cape Byron in Australia. Migaloo has several physical characteristics that can be identified; his dorsal fin is somewhat hooked, and his tail flukes have a unique shape, with edges that are spiked along the lower trailing side.[83] In July 2022, concerns arose after a white whale washed up on the shores of Mallacoota beach, however after genetic testing, and noting that the carcass was of a female whale while Migaloo is male, it was confirmed by experts to not be Migaloo.[84][85]

In 1985, Humphrey swam into San Francisco Bay and then up the Sacramento River towards Rio Vista.[86] Five years later, Humphrey returned and became stuck on a mudflat in San Francisco Bay immediately north of Sierra Point below the view of onlookers from the upper floors of the Dakin Building. He was twice rescued by the Marine Mammal Center and other concerned groups in California.[87] He was pulled off the mudflat with a large cargo net and the help of the US Coast Guard. Both times, he was successfully guided back to the Pacific Ocean using a "sound net" in which people in a flotilla of boats made unpleasant noises behind the whale by banging on steel pipes, a Japanese fishing technique known as oikami. At the same time, the attractive sounds of humpback whales preparing to feed were broadcast from a boat headed towards the open ocean.[88]

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) The humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) is a species of baleen whale. It is a rorqual (a member of the family Balaenopteridae) and is the only species in the genus Megaptera. Adults range in length from 14–17 m (46–56 ft) and weigh up to 40 metric tons (44 short tons). The humpback has a distinctive body shape, with long pectoral fins and tubercles on its head. It is known for breaching and other distinctive surface behaviors, making it popular with whale watchers. Males produce a complex song typically lasting 4 to 33 minutes.

Found in oceans and seas around the world, humpback whales typically migrate up to 16,000 km (9,900 mi) each year. They feed in polar waters and migrate to tropical or subtropical waters to breed and give birth. Their diet consists mostly of krill and small fish, and they use bubbles to catch prey. During the wintertime, they rely on their blubber storage for their energyThey are promiscuous breeders, with both sexes having multiple partners. Orcas are the main natural predators of humpback whales.

Like other large whales, the humpback was a target for the whaling industry. Humans once hunted the species to the brink of extinction; its population fell to around 5,000 by the 1960s. Numbers have partially recovered to some 135,000 animals worldwide, while entanglement in fishing gear, collisions with ships, and noise pollution continue to affect the species.