Biology

provided by Arkive

Polynesian megapodes are thought to be primarily monogamous, with pairs defending a shared territory, although roosting in different trees at night. Duets frequently performed by pairs may have a territorial function, but also indicate long-lasting pair bonds, serving to announce, form and strengthen those bonds. Polynesian megapodes nest in burrows and provide no parental care after the egg has been laid, so rely on thermally heated soil on volcanic islands to incubate the egg. Females produce eggs year-round, with one large egg laid at a time in communal burrows that are used repeatedly over decades. Between 12 and 16 eggs are produced per year. Chicks hatch underground after incubating for 50 to 80 days, and then dig themselves out (4). Since offspring must live independently from their parents immediately after hatching and be able to fend for themselves, they hatch at a large and advanced stage of development (4) and can fly immediately after they emerge from the ground (6).

The Polynesian megapode forages for food in leaf-litter and top soil, feeding mainly on insects and worms, but also taking small reptiles, seeds and small fruit (5). Mated pairs forage together and females frequently feed on food items uncovered by the male (4).

Conservation

provided by Arkive

The Polynesian megapode is legally protected, although in practice there is no real enforcement, and egg-collecting urgently needs to be brought under control. From 1991 to 1993, 60 eggs were introduced on Late Island, buried at volcanically heated sites, and 35 eggs and chicks were transferred to Fonualei, both islands being uninhabited, rarely visited, and with appropriate egg-laying conditions. While surveys suggest the reintroduction on Late failed, the now established population on Fonualei is a fantastic conservation success story, and provides new hope for the future of this rare bird. It has been advocated that Fonualei should be given Reserve status, and if achieved, this volcanic island may prove to be the safe refuge that ensures the Polynesian megapodes long-term survival (5). However, there is always the threat of eruption, which could potentially destroy the Fonualei population completely, and thus this species' restricted range leaves it in an extremely vulnerable position.

Description

provided by Arkive

Megapodes are so named because of their unusually large feet (3). This small megapode has a mostly brown-grey plumage, paler on the head and neck and browner on the back and wings, and yellow-orange legs and beak (4). Feathers of the face and throat are sparse, allowing the red skin beneath to show through, and there is a short, rounded crest on the back of the head. The duet between male and female pairs consists of a three-part whistle, kway-kwee-krrrr, from the male and a krrrr sound from the female (5).

Habitat

provided by Arkive

Inhabits broadleaved forest ranging from secondary to mature. As this bird uses the heat of hot volcanic ash to incubate its eggs, its nesting sites are confined to areas of loose soil close to volcanic vents, in forest, in open ash, or on beaches of crater lakes (5).

Range

provided by Arkive

The Polynesian megapode naturally occurs on the island of Niuafo'ou (35 km²) (2), and a reintroduced population exists on Fonualei, both in the Kingdom of Tonga, South Pacific (5).

Status

provided by Arkive

Classified as Endangered on the IUCN Red List 2006 (1).

Threats

provided by Arkive

The Polynesian megapode occupies a precarious existence, being restricted to just two tiny islands, with the Niuafo'ou population declining due to over-harvesting and predation. All nesting sites on Niuafo'ou are harvested by the local human population, with at least 50 % of all eggs being collected or destroyed. Adults are also hunted on a smaller scale, and both adults and chicks suffer from predation by feral cats and dogs. Pigs may pose an additional threat by competing for food. Fortunately, Fonualei is uninhabited and little-visited so the population there is relatively safe from the threats of hunting and human disturbance (5). In 2003 an incredible 300 to 500 birds were estimated to exist on the island, a significant increase from the 35 eggs and chicks that were introduced in 1993. Following this remarkable discovery, which effectively doubled the total known population of Polynesian megapode, the species was downlisted from Critically Endangered to Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (5) (3).

Tongan megapode

provided by wikipedia EN

The Tongan megapode (Megapodius pritchardii) is a species of bird in the megapode family, Megapodiidae, currently endemic to Tonga. The species is also known as the Polynesian megapode, and as the Niuafo'ou megapode after the island of Niuafo'ou to which it was restricted for many years. The specific epithet honours British consul William Thomas Pritchard.

Distribution and habitat

The Tongan megapode is the only remaining species of megapode in Tonga out of the four or five species that were present on the islands in prehuman times (as shown through the fossil record), and indeed the only species of megapode that survives in Polynesia.[2] Similar extinctions occurred in Fiji and New Caledonia, which apparently had three species in prehistory. The species itself once had a more widespread distribution, occurring across most of Tonga, Samoa and Niue.[3] The cause of all these extinctions and declines was the arrival of humans on the islands, and the associated predation on adults and particularly eggs, as well as predation by introduced species.

On Niuafo'ou the small human population and remoteness of its habitat probably saved the species. The only megapode to survive human arrival in Western Polynesia, "the megapode nesting grounds were carefully controlled by the ruling chief, thus assuring the continued survival of this population."[4]

Its natural habitat is tropical moist lowland forests. On Niuafo'ou it is most common on the central caldera. The Tongan megapode, like all megapodes, does not incubate its eggs by sitting on them; instead the species buries them in warm volcanic sands and soil and allows them to develop. On islands in former parts of its range without volcanoes it presumably created mounds of rotting vegetation and laid the eggs there.[2] The young birds are capable of flying immediately after hatching.[5]

Status and conservation

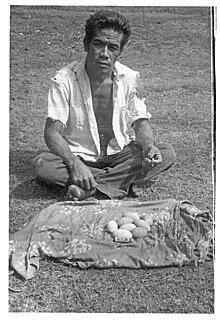

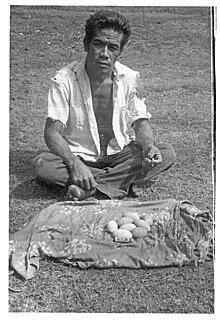

Eggs of the Malau (Megapodius pritchardii), gathered at Lake Vai Lahi (

Niuafoʻou) in 1967.

The Tongan megapode is principally threatened by the same factors that caused its decline in the rest of Polynesia. Its eggs are still harvested by local people in spite of theoretical government protection, and some hunting still occurs. The species is apparently afforded some protection by the difficulty in reaching its habitat.[5] Because of the vulnerability of the single population an attempt was made to translocate eggs of this species to new islands, Late and Fonualei. The translocation was successful on Fonualei and an estimated 350–500 birds now breed there, but surveys of Late subsequently found that the translocation there had failed.[6]

References

-

^ BirdLife International (2019). "Megapodius pritchardii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T22678625A156113936. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T22678625A156113936.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

-

^ a b Steadman D, (2006). Extinction and Biogeography in Tropical Pacific Birds, University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-77142-7 pp. 291–292

-

^ Steadman, David W.; Worthy, Trevor H.; Anderson, Atholl & Walter, Richard (2000). "New species and records of birds from prehistoric sites on Niue, southwest Pacific". Wilson Bulletin. 112 (2): 165–186. doi:10.1676/0043-5643(2000)112[0165:NSAROB]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86588636.

-

^ Kirch, Patrick Vinton; Roger C. Green (2001). Hawaiki, Ancestral Polynesia. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 117. ISBN 0-521-78879-X.

-

^ a b Weir, D (1973). "Status and habits of Megapodius pritchardii". Wilson Bulletin. 85 (1): 79–82. JSTOR 4160299.

-

^ Birdlife International (2004) "Megapode survey too late" Downloaded 29 July 2008

- license

- cc-by-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Wikipedia authors and editors

Tongan megapode: Brief Summary

provided by wikipedia EN

The Tongan megapode (Megapodius pritchardii) is a species of bird in the megapode family, Megapodiidae, currently endemic to Tonga. The species is also known as the Polynesian megapode, and as the Niuafo'ou megapode after the island of Niuafo'ou to which it was restricted for many years. The specific epithet honours British consul William Thomas Pritchard.

- license

- cc-by-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Wikipedia authors and editors