en

names in breadcrumbs

Humans have few natural predators and often sit at or near the top of the food chain in regional ecosystems. Humans are sometimes opportunistically preyed on by large wild cats, such as tigers (Panthera tigris) and lions (Panthera leo). Other instances of large, carnivorous animals eating humans are often cases of mistaken identity or are opportunistic events. This includes cases involving large sharks, bears, monitor lizards, and crocodiles.

Known Predators:

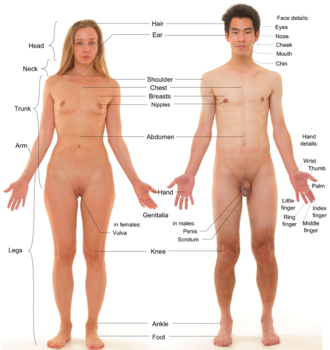

Humans are an exceptionally diverse species morphologically and many aspects of size vary substantially with environmental factors such as nutritional status. Historically there has been an effort to organize human physical variation into "races," although there is no scientific basis for the application of a race concept to human variation. Human physical variation is continuous and available evidence suggests that gene flow among human populations throughout their history has been the rule rather than the exception.

Humans are characterized by their bipedalism and their lack of significant body hair. Males are generally larger than females, with more pronounced muscle development and generally more hair on the face and torso than females.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry ; polymorphic

Sexual Dimorphism: male larger; sexes shaped differently

Human lifespans vary tremendously with nutritional status and exposure to diseases and trauma. Humans can live more than 100 years; the longest lived human that has been documented was 122 years old. Most humans live 50 to 80 years old, providing they survive their most vulnerable childhood years. Average life expectancy in many parts of the developing world is from less than 40 years old to 65 years old. In the developed world average life expectancy can be over 80 years old.

Typical lifespan

Status: wild: 32 to 84 years.

Humans are found in all terrestrial habitats worldwide. Humans extensively modify habitats as well, creating areas that are habitable by a much reduced set of other organisms, as in urban and agricultural areas. With the aid of technologies such as boats, humans also venture into many aquatic habitats, primarily to obtain food.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; tropical ; polar ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: tundra ; taiga ; desert or dune ; savanna or grassland ; chaparral ; forest ; rainforest ; scrub forest ; mountains

Wetlands: marsh ; swamp

Other Habitat Features: urban ; suburban ; agricultural ; riparian ; estuarine ; intertidal or littoral ; caves

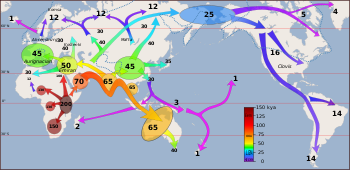

Humans are currently found throughout the world; in permanent settlements on all continents except Antarctica and on most habitable islands in all of the oceans. All available evidence suggests that humans originated in Africa.

Anatomically modern Homo sapiens populations are known from the Middle East as long as 100,000 years ago, from east Asia as long as 67,000 years ago, and southern Australia as long as 60,000 years ago. European Homo sapiens fossils are known from 35,000 years ago. Homo sapiens populations were once thought to have colonized the New World approximately 11 to 13,000 years ago, but recent research indicates earlier dates of colonization. This is an area of active research.

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native ); palearctic (Native ); oriental (Native ); ethiopian (Native ); neotropical (Native ); australian (Native ); oceanic islands (Native )

Other Geographic Terms: cosmopolitan

Humans generally eat a highly variable omnivorous diet. The components of diets vary tremendously with regional availability of foods. Some human cultures restrict their diet to a vegetarian one, relying on plant sources of proteins. Foods are often extensively prepared and stored for future use. The use of fungal colonies, such as yeasts, for creating cultured foods, such as beer, bread, and cheeses, is widespread.

Animal Foods: birds; mammals; amphibians; reptiles; fish; eggs; blood; body fluids; carrion ; insects; terrestrial non-insect arthropods; mollusks; terrestrial worms; aquatic crustaceans; echinoderms; other marine invertebrates

Plant Foods: leaves; roots and tubers; wood, bark, or stems; seeds, grains, and nuts; fruit; nectar; pollen; flowers; sap or other plant fluids; algae; macroalgae

Other Foods: fungus; microbes

Foraging Behavior: stores or caches food

Primary Diet: omnivore

Humans act as top predators in many ecosystems, although they are also sometimes preyed on by larger predators, such as tigers. Humans modify habitats and ecological communities in countless ways, often substantially changing the interactions of nearly all other species in those habitats.

Humans are parasitized by many species of internal and external parasites. Some research suggests that hairlessness in humans is an adaptation to reduce ectoparasite loads.

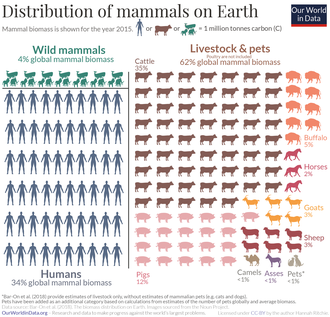

Humans and human societies have evolved multiple relationships with other species, including commensal species and domesticated and companion species. Human commensals are too numerous to mention, but some important commensal species are house mice (Mus musculus), black rats (Rattus rattus), Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus), and Oriental cockroaches (Periplaneta americana). Important domestic species include domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris), pigs (Sus scrofa), cattle (Bos taurus), sheep (Ovis aries), goats (Capra hircus), chickens (Gallus gallus), guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus), horses (Equus caballus), llamas (Lama glama), camels (Camelus species), turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo), honeybees (Apis mellifera), and many other animals. Humans have also domesticated many species of plants for food and other uses, such as corn (Zea mays), rice (Oryza sativa), wheat (Triticum aestivum), manioc (Manihot esculenta), apples (Malus domestica), and soy (Glycine max).

Ecosystem Impact: creates habitat

Mutualist Species:

Commensal/Parasitic Species:

Human interactions are often complex and negative at interpersonal levels and among social groups, cultures, and governments. Human activities often destroy or transform ecosystems, and these changes can have negative economic and/or medical impacts on other human populations.

Human populations are not monitored by conservation agencies. Although human populations worldwide are large and growing, some regional or isolated populations may be in decline as a result of economic disadvantage, disease, habitat degradation, emigration, and cultural erosion.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

State of Michigan List: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

Like most primates, humans use vision extensively in perception and communication. Humans have excellent color vision, although visual acuity in low light is limited. Humans also use sounds extensively. Human languages represent one of the most complex systems of communication in the animal world, and the diversity of human languages is astounding. Touch is an important mode of perception, it is especially important in close social bonds. Humans have a moderately well developed sense of smell and taste, which is used to determine the suitability of foods and discover information about the environment and conspecifics.

The evolution of complex language is considered one of the hallmarks of Homo sapiens. Archaic humans were capable of complex language, although Homo sapiens anatomy seems to have evolved to favor the production of complex sounds in anatomically modern humans.

Communication Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Other Communication Modes: pheromones

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Earliest Homo sapiens appeared approximately 700,000 years ago, although anatomically modern humans are known from about 100,000 years ago. Patterns of colonization of the world by ancient humans and the details of interactions between ancient Homo sapiens and co-occurring Homo species are areas of active research.

Human cultures are marked by a wide range of approaches to mating. Child-rearing in most cultures is accomplished with some degree of help and cooperation from other members of the group, including related and unrelated members.

Mating System: monogamous ; polyandrous ; polygynous ; polygynandrous (promiscuous) ; cooperative breeder

Humans are capable of breeding throughout the year. Gestation length is 40 weeks on average, a fairly long gestation length for a primate species with altricial young. Typically one young is born, although twins occur occasionally and multiple births rarely. Interbirth intervals, birth weights, time to weaning, independence, and sexual maturity all vary substantially with nutritional status of mothers and young and are influenced by cultural practices.

Breeding interval: Human females can reproduce up to once every 10 months, although typical birth intervals are longer and vary substantially.

Breeding season: Humans can breed at any time of the year.

Range number of offspring: 1 (low) .

Average gestation period: 40 weeks.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; year-round breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; viviparous

Human infants are born in an altricial state and require intense and long-term care to ensure survival. Parental care is variable across human cultures, but generally the mother plays a large role in caring for infants through weaning. Family members and unrelated community members also often play large roles in caring for young. Human young experience an extended period of adolescence in which many essential skills and cultural knowledge are learned and practiced. Human social structures are complex and frequently young remain part of the same larger social groups as their parents and their paternal and maternal families. Social stature of parents often also plays a large role in the social stature of the young.

Parental Investment: altricial ; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Male, Female, Protecting: Male, Female); pre-independence (Provisioning: Male, Female, Protecting: Male, Female); post-independence association with parents; extended period of juvenile learning; inherits maternal/paternal territory; maternal position in the dominance hierarchy affects status of young

Human beings, humans, or Homo sapiens sapiens (Homo sapiens is latin and refers to the wise or knowing human) are bipedal primates in the family Hominidae. DNA evidence indicates that modern humans originated in Africa about 250,000 years ago. Humans have a highly developed brain, capable of abstract reasoning, language, introspection, and emotion. This mental capability, combined with an erect body carriage that frees the forelimbs (arms) for manipulating objects, has allowed humans to make far greater use of tools than any other species. Humans currently inhabit every continent on Earth, except Antarctica (although several governments maintain seasonally-staffed research stations there). Humans also now have a continuous presence in low Earth orbit, occupying the International Space Station. The human population on Earth is greater than 6.7 billion, as of July, 2008.

Like most primates, humans are social by nature. However, they are particularly adept at utilizing systems of communication for self-expression, exchanging of ideas, and organization. Humans create complex social structures composed of many cooperating and competing groups, from families to nations. Social interactions between humans have established an extremely wide variety of traditions, rituals, ethics, values, social norms, and laws, which together form the basis of human society. Humans have a marked appreciation for beauty and aesthetics, which, combined with the desire for self-expression, has led to innovations such as culture, art, literature and music.

Humans are notable for their desire to understand and influence the world around them, seeking to explain and manipulate natural phenomena through science, philosophy, mythology and religion. This natural curiosity has led to the development of advanced tools and skills; humans are the only currently known species known to build fires, cook their food, clothe themselves, and manipulate and develop numerous other technologies. Humans pass down their skills and knowledge to the next generations through education.

The scientific study of human evolution encompasses the development of the genus Homo, but usually involves studying other hominids and hominines as well, such as Australopithecus. Modern humans are defined as the Homo sapiens species, of which the only extant subspecies - our own - is known as Homo sapiens sapiens. Homo sapiens idaltu (roughly translated as elder wise human), the other known subspecies, is now extinct. Anatomically modern humans first appear in the fossil record in Africa about 130,000 years ago, although studies of molecular biology give evidence that the approximate time of divergence from the common ancestor of all modern human populations was 200,000 years ago.

The closest living relatives of Homo sapiens are the two chimpanzee species: the Common Chimpanzee and the Bonobo. Full genome sequencing has resulted in the conclusion that after 6.5 [million] years of separate evolution, the differences between chimpanzee and human are just 10 times greater than those between two unrelated people and 10 times less than those between rats and mice. Suggested concurrence between human and chimpanzee DNA sequences range between 95% and 99%. It has been estimated that the human lineage diverged from that of chimpanzees about five million years ago, and from that of gorillas about eight million years ago. However, a hominid skull discovered in Chad in 2001, classified as Sahelanthropus tchadensis, is approximately seven million years old, which may indicate an earlier divergence.

The Recent African Origin (RAO), or the - out-of-Africa-, hypothesis proposes that modern humans evolved in Africa before later migrating outwards to replace hominids in other parts of the world. Evidence from archaeogenetics accumulating since the 1990s has lent strong support to RAO, and has marginalized the competing multiregional hypothesis, which proposed that modern humans evolved, at least in part, from independent hominid populations. Geneticists Lynn Jorde and Henry Harpending of the University of Utah propose that the variation in human DNA is minute compared to that of other species. They also propose that during the Late Pleistocene, the human population was reduced to a small number of breeding pairs, no more than 10,000, and possibly as few as 1,000, resulting in a very small residual gene pool. Various reasons for this hypothetical bottleneck have been postulated, one being the Toba catastrophe theory.

Human evolution is characterized by a number of important morphological, developmental, physiological and behavioural changes, which have taken place since the split between the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees. The first major morphological change was the evolution of a bipedal locomotor adaptation from an arboreal or semi-arboreal one, with all its attendant adaptations, such as a valgus knee, low intermembral index (long legs relative to the arms), and reduced upper-body strength.

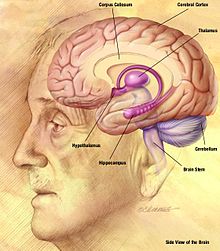

Later, ancestral humans developed a much larger brain â typically 1,400 cm³ in modern humans, over twice the size of that of a chimpanzee or gorilla. The pattern of human postnatal brain growth differs from that of other apes (heterochrony), and allows for extended periods of social learning and language acquisition in juvenile humans. Physical anthropologists argue that the differences between the structure of human brains and those of other apes are even more significant than their differences in size.

Other significant morphological changes included: the evolution of a power and precision grip; a reduced masticatory system; a reduction of the canine tooth; and the descent of the larynx and hyoid bone, making speech possible. An important physiological change in humans was the evolution of hidden oestrus, or concealed ovulation, which may have coincided with the evolution of important behavioural changes, such as pair bonding. Another significant behavioural change was the development of material culture, with human-made objects becoming increasingly common and diversified over time. The relationship between all these changes is the subject of ongoing debate.

The forces of natural selection continue to operate on human populations, with evidence that certain regions of the genome display directional selection in the past 15,000 years.

This description from WikiPedia, 3rd August 2008: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homo_sapiens

There are several different kinds of immune system cells. Below is an in-depth description of what they are and do:

T lymphocyte cell

There are two types of T lymphocyte cell. The first one is the CD4+ T Cell, also known as the T helper. The job of the CD4+ T Cell is to secrete special chemicals that activate the other ImmuneSystem Cells (immune cells). CD4+ T Cells are the most importantcells in the immune system of the human body.

The other type of T lymphocyte is the CD8+ T Cell, also known as the T killer cell. The T killer cell killstumor cells and virus-infected cells. The CD8+ TCell, along with the Natural Killer Cell, protects the body from threats that cannot be combated directly.

Natural Killer Cells

Natural killer cells, also known asNK cells, performs the same role as the CD8+ T Cell, except that it performs its role with or without secretions from the CD4+ T Cells.The natural killer cells fuction as a back-up in the face of heavy cancer or HIV. This allows the human body to continue to live for a while longer even after the CD4+ T Cells communication system has collapsed.

B cells

The role of a B cell is to manufacture antibodies. This is crucial because antibodies mark a pathogen for destruction. Because of this, B cells are the second most important cell in the immune system.

Granulocytes

Granulocytes are tied in importance with the B cells. Even though it is important to mark pathogens for destruction, it is also vital to have some cells to actually destroy the pathogen.

There are three types of granulocytes: neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils. All three types of granulocytes gobble up bacteria. But basophils also play a role in allergies, and neutrophils occasionally help with eating up tumors.

In short, granulocytes make up the bulk of the immune system.

Macrophages

Macrophages are important cells. Their role is to pick up foreign materials and present the antigens to CD4+ T Cells or B cells. This is the beginning of the immune process. However, macrophages are not that important because there is another type of cell called a dendrite that does the same work the macrophages do.

Dendritic cells

Another cell type, adressed only recently, is the dendritic cell. As stated above, dendritic cells perform the same role that macrophages do. They are in fact, better at presenting antigens because they are faster and consume less energy. However, there is a downside.

The downside is that dendritic cells bind a high amount of HIV virus. During an activation event, dendritic cells transmit HIV to the CD4+ T Cells, which leads to collapse of the immune system.

Pretty much all of human behavior comes from our brains, and ultimately our neurons.

There are four types of neurons:

The bipolar neuron (interneuron), the unipolar neuron (sensory neuron), the multipolar neuron (motor neuron) and finally the pyramid cell.

Neurons have a great diversity of lenghts. The shortest neurons are less than 1 millimeterlong and the longest neurons up toa meter long!

Neurons have three crucial parts: the soma, the dendrites and the axon. The soma is where the nucleus and the cell proper of the neuron is. The dendrites recieve information from other neurons and transmit it to the soma. The axon is the "talker" sending information from the soma of the neuron to other neurons. The axon is long and thin, makes up most of the neurons length and depending what type of neuron the cell is, the axon could be encased in a "protective layer of fat called the Myelin Sheath". In contrast, dendrites are numerous, fat and bushy.

If the Myelin Sheath is broken or worn out, people get a mental condition called Multiple Sclerosis. Eventually,a worn out Myelin Sheath leads to total loss of muscle control.

When the soma of a neuron wants to send a message, it fires an electric current down the axon and thensecretes special chemicals to breach a gap between the two neurons called a synaptic gap. The synaptic gap is only one millionth of an inch wide, so it is relatively easy to breach.

There are many different chemicals in the brainthat trigger or calm down neurons.

Homo sapiens (del llatín, homo 'home' y sapiens 'sabiu') ye una especie del orde de los primates perteneciente a la familia de los homínidos. Tamién son conocíos so la denominación xenérica de «homes», anque esi términu ye ambiguu y úsase tamién pa referise a los individuos de sexu masculino ysobremanera, a los varones adultos.[2][3] Los seres humanos tienen capacidaes mentales que-yos dexen inventar, aprender y utilizar estructures llingüístiques complexes, lóxicas, matemátiques, escritura, música, ciencia, y teunoloxía. Los humanos son animales sociales, capaces de concebir, tresmitir y aprender conceutos totalmente astractos.

Considérense Homo sapiens de forma indiscutible a los que tienen tantu les carauterístiques anatómica de les poblaciones humanes actuales como lo que se define como «comportamientu modernu». Los restos más antiguos de Homo sapiens atopar en Marruecos con 315 000 años.[4] La evidencia más antigua de comportamientu modernu son les de Pinnacle Point (Sudáfrica) con 165 000 años.

Pertenez al xéneru Homo que foi más diversificáu y, mientres l'últimu millón y mediu d'años incluyía otres especies yá estinguíes. Dende la estinción del Homo neanderthalensis, fai 28 000 años, y del Homo floresiensis fai 12 000 años (debatible), el Homo sapiens ye la única especie conocida del xéneru Homo qu'entá perdura.

Hasta apocayá, la bioloxía utilizaba un nome trinomial —Homo sapiens sapiens— pa esta especie, pero más apocayá refugóse el nexu filoxenéticu ente'l neandertal y l'actual humanidá,[5] polo que s'usa puramente'l nome binomial. Homo sapiens pertenez a un fonduxe de primates, los hominoideos. Anque'l descubrimientu de Homo sapiens idaltu en 2003 fadría necesariu volver al sistema trinomial, la posición taxonómica d'esti postreru ye entá incierta.[6] Evolutivamente estremar n'África y de esi ancestru surdió la familia de la que formen parte los homínidos.

Filosóficamente, el ser humanu se definió y redefinió a sigo mesmu de numberoses maneres al traviés de la hestoria, otorgándose d'esta manera un propósitu positivu o negativu respectu de la so propia esistencia. Esisten diversos sistemes relixosos ya ideales filosóficos que, d'alcuerdu a una diversa gama de culturas ya ideales individuales, tienen como propósitu y función responder delles d'eses interrogantes esistenciales. Los seres humanos tienen la capacidá de ser conscientes de sigo mesmos, lo mesmo que d'el so pasáu; saben que tienen el poder d'entamar, tresformar y realizar proyeutos de diversos tipos. En función a esta capacidá, crearon diversos códigos morales y dogmas empobinaos direutamente al manexu d'estes capacidaes. Amás, pueden ser conscientes de responsabilidaes y peligros provenientes de la naturaleza, asina como d'otros seres humanos.

El nome científicu, ye l'asignáu pol naturalista suecu Carlos Linneo (1707-1778) en 1758,[7] alude a la traza biolóxica más carauterísticu: sapiens significa «sabiu» o «capaz de conocer», y refierse a la considerancia del ser humanu como «animal racional», al contrariu que toles otres especies. Ye precisamente la capacidá del ser humanu de realizar operaciones conceptuales y simbóliques bien complexes —qu'inclúin, por casu, l'usu de sistemes llingüísticos bien sofisticaos, el razonamientu astractu y les capacidaes d'introspeición y especulación— unu de les sos traces más destacaes. Posiblemente esta complexidá, fundada neurológicamente nun aumentu del tamañu del celebru y, sobremanera, nel desenvolvimientu del lóbulu fronteru, seya tamién una de les causes, al empar que productu, de les bien complexes estructures sociales que'l ser humanu desenvolvió, y que formen una de les bases de la cultura, entendida biológicamente como la capacidá pa tresmitir información y vezos por imitación ya instrucción, en cuenta de por heriedu xenéticu. Esta propiedá nun ye esclusiva d'esta especie y ye importante tamién n'otros primates.

Linneo clasificó al home y a los monos nun grupu que llamó antropomorfos, como subconxuntu del grupu cuadrúpedos, pos entós nun reconocía signos orgánicos que-y dexaren allugar al ser humanu nun llugar privilexáu de la escala de los vivientes. Años más tarde, nel prefaciu de Fauna suecica, manifestó que clasificara al home como cuadrúpedu porque nun yera planta nin piedra, sinón un animal, tantu pol so xéneru de vida como pola so locomoción y porque amás, nun pudiera atopar un solu calter distintivu pol cual l'home estremar del monu; n'otru contestu afirmó sicasí que considera al home como'l fin últimu de la creación. A partir de la décima edición de Systema naturae reemplazó a los cuadrúpedos polos mamíferos y como primer orde d'estos, punxo a los primates, ente los cualos asitió al home. Linneo tuvo'l méritu de dar orixe a un nuevu ya inmensu campu epistemolóxico, el de l'antropoloxía, magar se llindó a enuncialo y nun lo cultivó. A él van tener qu'unviase tolos científicos posteriores, tantu pa retomar les sos definiciones como pa criticales. En 1758 definir al Homo sapiens linneano como una especie diurna que camudaba pola educación y el clima.

Linneo nun designó un holotipo pa Homo sapiens, pero en 1959 William Stearn propunxo al propiu Linneo, padre de la moderna taxonomía, como lectotipo pa la especie. Con posterioridá espublizóse la idea de que fuera sustituyíu por Edward Acope, pero esta propuesta nun llegó a formalizase, asina que siguen siendo los restos de Linneo soterraos en Uppsala el tipu nomenclatural -que tien de considerase simbólicu- pa la especie Homo sapiens.[8]

Na actualidá esisten defensores d'incluyir al ser humanu, chimpancé (Pan troglodytes) y bonobo (Pan paniscus) nel mesmu xéneru, dada la cercanía filoxenética, que ye más estrecha que la que s'atopa ente otres especies animales que sí tán arrexuntaes genéricamente.[9]

El ser humanu ye un ser vivu, y como tal ta compuestu por sustances químiques llamaes biomoléculas, por célules y realiza los trés funciones vitales: nutrición, rellación y reproducción.[10]

Amás, el cuerpu ye un organismu pluricelular, esto ye, ta formáu por munches célules, ente les cualos esisten diferencies d'estructures y de función.[10]

Per otra parte, el ser humanu ye un animal, pos tien célules eucariotes, esto ye, presenta orgánulos celulares especializaos nuna función determinada y la so material xenético atópase protexíu por una envoltura; y presenta nutrición heterótrofa, esto ye, que pa llograr la so propia materia orgánico alimentar d'otros seres vivos.[10]

Tocantes a la so locomoción y movimientu, ye unu de los más plásticos del reinu animal, pos esiste una amplia gama de movimientos posibles, lo que-y capacita p'actividaes como'l arte escénico y la danza, el deporte y una tremera d'actividaes cotidianes. Coles mesmes destaca l'habilidá de manipulación, gracies a los pulgares oponibles, que-y faciliten la fabricación y usu de preseos.

La especie humana tien un vultable dimorfismu sexual nel nivel anatómicu, por casu, la talla media actual ente los varones caucásicos (si crecen bien nutríos y con pocu estrés) escontra los 21 años ye de 1.75 m, la talla media de les muyeres caucásiques nes mesmes condiciones ye de 1.62 m, y los pesos promedios respeutivos son de 75 kg y 61 kg respeutivamente; anque sí se notó un enclín secular» al aumentu de les talles (especialmente mientres el sieglu XX).

La mente refierse colectivamente a aspeutos del entendimientu y conciencia que son combinaciones de capacidaes como'l raciociniu, la perceición, la emoción, la memoria, la imaxinación y la voluntá. La mente, pa los materialistes, ye un resultáu de l'actividá del celebru.

El términu pensamientu define tolos productos que la mente puede xenerar incluyendo les actividaes racionales del intelectu o les astraiciones de la imaxinación; tou aquello que seya de naturaleza mental ye consideráu pensamientu, bien sían estos astractos, racionales, creativos, artísticos, etc. Xuntu colos cetáceos cimeros (delfines y ballenes), los homininos de los xéneros Gorilla y Pan y los elefantes, algama'l mayor desenvolvimientu na escala evolutiva y entá munches de les sos interaiciones sonnos desconocíes.

El ser humanu ye un animal omnívoru.[11][12] Nes primeres especies del xéneru Homo, el pasu d'una alimentación eminentemente vexetariano a la inclusión de la carne na dieta nun se debió a cuestiones culturales, sinón a los desaxustes metabólicos provocaos por un mayor desenvolvimientu cerebral.[11] Sicasí, nel humanu, una dieta demasiáu rica en proteínes precisa'l complementu de carbohidratos y grases, de lo contrario pueden apaecer faltes nutricionales importantes que pueden inclusive provocar la muerte.[11] Por ello, l'alimentación del ser humanu basar na combinación de materia vexetal con carne,[11] anque hai humanos qu'opten por cuenta de voluntá propia o razones médiques a consumir dietes vexetarianes.

La especie humana ye ente los seres vivos pluricelulares actuales una de les más llonxeves; tiénense documentados casos de llonxevidá que devasen los cien años. Tal llonxevidá ye un calter genotípico que, sicasí, ten de ser coadyuvado por condiciones vivenciales favorables. Nel Imperiu romanu, escontra l'añu 1 d. C., la esperanza de vida rondaba namái los venticinco años, debíu en gran parte a la elevada mortalidá infantil[ensin referencies]. La edá de la pubertá ye aprosimao a los once años nes neñes y a los trelce años nos neños, anque les edaes varien según la persona.

Como tolos mamíferos, el ser humanu tien unos comportamientos reproductivu y sexual. Pero a diferencia de la mayoría d'ellos nun tien una dómina reproductiva estacional determinada, calteniendo actividá sexual y fertilidá nes femes a lo llargo de too l'añu. Les muyeres tienen un ciclu d'ovulación aprosimao mensual, mientres el cual producen óvulos y pueden ser fecundaes, en casu contrariu tienen la menstruación, que ye la eliminación al traviés de la natura de los texíos y sustances rellacionaos a la producción de célules sexuales.

Pero'l comportamientu sexual humanu nun ta namái supeditáu a les funciones reproductives, sinón que, de manera similar a otros simios antropoides, tien fines recreativos y sociales. Nel contautu sexual búscase tantu'l prestar como la comunicación afeutiva. Ye una parte importante de les rellaciones de pareya y tamién se considera importante nes necesidaes psicolóxiques del invididuo anque nun tenga una rellación de pareya.

La sexualidá humana pue ser heterosexual o homosexual. Delles teoríes suxuren que'l ser humanu ye bisexual pero xeneralmente con preferencia pola homosexualidá o la heterosexualidá, de manera distinta en cada individuu. Esto asemeya un pocu a lo estudiao n'otros primates cercanos como'l bonobo.

Dende'l puntu de vista psicoanalíticu, Ente otres implicaciones, la importancia del llinguaxe simbólicu nel Homo sapiens, fai que los significantes sían los soportes del pensar o los pensamientos. Na nuesa especie, el pensar humanu, a partir de los trés años y mediu d'edá faise prevalentemente simbólicu.

Acomuñáu colo anterior (y esto esplicar el psicoanálisis), tien de notase que la especie humana ye práuticamente la única que se caltien en celu sexual continuu: ye realmente destacable que na especie humana nun esista un estro puramente dichu. Nes muyeres esiste un ciclu d'actividá ovárica en virtú del cual esisten cambeos fisiolóxicos en tol so sistema reproductivu y del cual deriven ciertos cambeos de conducta. Sicasí, como nes muyeres l'aceptación sexual non se circunscribe a una parte del ciclu reproductivu, nun se debería usar el términu "estro" o "celu" nel ser humanu, yá que l'aceptación sexual ye independiente del so ciclu reproductivu. Yá ente chimpancés y, sobremanera, bonobos, nótase una conducta próxima.

Agora bien; dada la dificultá de vivir solamente practicando rellaciones sexuales, un "mecanismu" evolutivu compensatoriu sería'l de la sublimación –la cual considérase acomuñada a la esistencia d'un llinguaxe y un pensar simbólicos–, si da una sublimación esto paez significar que, tamién se da una represión (nel sentíu freudiano) qu'anicia a lo inconsciente. El Homo sapiens ye, nesti sentíu, un animal pulsional. Según la reflexoloxía de Pavlov el Homo sapiens non acutar a un "primer sistema de señales" (el d'estímulo/respuesta y respuesta a un estímulu substitutivo), sinón que'l ser humanu atopar nun nivel de "segundu sistema de señales". Esti segundu sistema ye, principalmente'l del llinguaxe simbólicu que dexa una heurística, que ye la capacidá pa realizar de forma inmediata innovaciones positives pa los sos fines.

Per otra parte, la especie humana ye de les poques, xuntu col bonobo (Pan paniscus) nel reinu animal que copula de frente, lo cual tien implicaciones emocionales de gran relevancia pa la especie.

Cabo anotar que col surdimientu de la teoría de la intelixencia emocional, dende la psicoloxía sistémica, el ser humanu nun tien d'amenorgar se a les sos pulsiones, que sublima o reprime, sinón que s'entiende como un ser sexuáu, que vive esta dimensión en rellación cola formación recibida na familia y la sociedá. La sexualidá fórmase entós dende los primeros años y vase entendiendo como una vivencia procesual acorde al so ciclu vital y el so contestu sociu-cultural.

A diferencia de lo qu'asocede na mayor parte de les otres especies sexuaes, la muyer sigue viviendo enforma tiempu tres la menopausia. Nes otres especies la fema suel finar al poco tiempu de llegada la mesma.

Pola indicada prematuración, el maduror sexu-xenital ye –en rellación a otres especies– bien tardida ente los individuos de la especie humana, anguaño en munches zones la menarquia ta asocediendo a los once años, esto significa que, anque'l maduror sexu-xenital ye siempres lenta na especie humana, esiste un adelantamientu de la mesma al respeutive de dómines pasaes (de la mesma suel dase una menopausia cada vez más tardida). Pero si'l maduror sexu-xenital ye tardida na especie humana, entá más suel selo'l maduror intelectual y, cuantimás la maduror emotivu.

A lo llargo de la hestoria fuéronse desenvolviendo distintes concepciones mítiques, relixoses, filosófiques y científiques respectu del ser humanu, caúna cola so propia esplicación sobre'l orixe del home, trescendencia y misión na vida.

Evolutivamente, en cuanto perteneciente al infraorden Catarrhini, Homo sapiens paez tener el so ancestru, xuntu con tolos primates catarrinos, nun periodu que va de los 50 a 33 millones d'años antes del presente (AP), unu de los primeres catarrinos, quiciabes el primeru, ye Propliopithecus, incluyendo a Aegyptopithecus, nesti sentíu, el ser humanu actual, al igual que primates del "Vieyu Mundu" con carauterístiques más primitives, probablemente baxe d'esa antigua especie.

Tocantes a la bipedestación, ésta reparar en ciertos primates a partir del Miocenu. Yá s'atopen exemplos de bipedación en Oreopithecus bambolii y la bipedestación paez ser común en Orrorin y Ardipithecus. Les mutaciones que llevaron a la bipedación fueron esitoses porque dexaba llibre les manes pa coyer oxetos y, particularmente, porque na marcha un homínidu aforra muncha más enerxía andando sobre dos piernes que sobre cuatro pates, puede acarretar oxetos mientres la marcha y otear más llueñe. Sicasí, de remontase la bipedestación a quiciabes a unos 6 millones d'años aP, l'andadura o forma de marcha típica del humanu consolídase aprosimao fai siquier unos 4 millones d'años con Australopithecus, previu a éstos los primates antropoides sofitaben tola planta del pie faciendo una flexón y descargando el pesu nel calcáneo, sicasí Australopithecus llogra una marcha bípeda eficiente, pos se noten claramente los cambeos anatómicos a nivel del pie, cuantimás del deu gordu; tamién afaciendo l'ángulu del fémur col cuerpu pal equilibriu, el cadril o maxana camuda a más robusta, curtia y cóncava (forma de concu); la columna pasó de ser un arcu en forma de C a una forma de S y el furacu de la base del craniu que conecta cola columna mover escontra alantre[13] como dirixiéndose al centru de gravedá de la cabeza.

Fai 1.5 millones d'años con Homo erectus o con Homo ergaster, l'andadura moderna implica la esistencia d'un pequeñu ángulu ente'l deu gordu y l'exa del pie, según la presencia del arcu llonxitudinal de la planta y una distribución medial del pesu (notar que nes muyeres l'andadura distribúi'l pesu más escontra les partes internes del pie por cuenta del mayor anchor de la maxana).[14]

Tolos cambeos reseñaos asocedieron nun periodu relativamente curtiu (anque se mida en millones d'años), esto esplica la susceptibilidá de la nuesa especie a afecciones na columna vertebral y na circulación sanguíneo y linfático (por casu, el corazón recibe -relativamente- "poca" sangre).

Lo que denominamos puramente «humanu», ye una referencia a l'apaición de la capacidá de fabricar ferramientes de piedra nun homínidu bípedu: Homo habilis, consideráu pola mayoría como la especie humana más primitiva, amosando amás medría na capacidá craneana con al respeutive de Australopithecus. Ye según establezse que fai unos 2.5 millones d'años, cola apaición del xéneru Homo, tómase como puntu d'entamu pal Paleolíticu o Edá de Piedra. Mayor ésitu evolutivu va tener Homo erectus, quien va llograr espandise por tou Eurasia.

Probablemente cuando los ancestros de Homo sapiens vivíen en selvas comiendo frutos, bayes y fueyes, abondoses en vitamina C, pudieron perder la capacidá metabólica, que tien la mayoría de los animales, de sintetizar nel so propiu organismu tal vitamina; yá antes paecen perder la capacidá de dixerir la celulosa. Tales perdes mientres la evolución implicaron sutiles pero importantes determinaciones: cuando les selves orixinales amenorgar o, por crecedera demográfica, resultaron superpoblaes, los primitivos homínidos (y depués los humanos) viéronse forzaos a percorrer importantes distancies, migrar, pa llograr nueves fontes de nutrientes, la perda de la capacidá de metabolizar ciertos nutrientes como la vitamina C sería compensada por una mutación favorable que dexa a Homo sapiens una metabolización óptima (ausente en primates) del almidón y asina una rápida y "barata" llogru d'enerxía, particularmente útil pal celebru. Homo sapiens paez ser una criatura bastante indefensa y como respuesta satisfactoria la única solución evolutiva que tuvo ye la so complejísimo sistema nerviosu central. Aguiyonáu principalmente pola busca de nueves fontes d'alimentación. Suxurióse la hipótesis de que la cefalización aumentó paralelamente a la medría de consumu de carne[ensin referencies], anque dicha hipótesis nun concordar col grau de cefalización desenvuelta polos animales carnívoros. L'habilidá humana pa dixerir alimentos con altu conteníu d'almidón podría esplicar l'ésitu del homo sapiens nel planeta, suxure un estudiu xenéticu.[15]

Denominar «humanos arcaicos», «Homo sapiens arcaicu» o tamién «pre-sapiens», a un ciertu númberu d'especies de Homo qu'entá nun son consideraos anatómicamente modernos. Tienen hasta 600 000 años d'antigüedá y tienen un tamañu cerebral cercanu al de los humanos modernos. L'antropólogu Robin Dunbar cunta que ye nesta etapa na cual apaez el llinguaxe humanu. La filiación d'estos individuos dientro del nuesu xéneru resulta entá revesosa.

Ente los humanos arcaicos tán consideraos Homo heidelbergensis, Homo rhodesiensis, Homo neanderthalensis y dacuando Homo antecessor; en 2010 añedióse a éstos el denomináu «home de Denísova»,[16] y en 2012 el denomináu «home del venáu coloráu» en China.[17] Yá que nun son sapiens, dellos especialistes prefieren llamalos a cencielles arcaicos primero que H. sapiens arcaicu.[18]

Denominar puramente Homo sapiens o anatómicamente modernos a individuos con una apariencia similar a la de los humanos modernos. Estos humanos pueden clasificase como premodernos, pos nellos nun se repara inda'l conxuntu de carauterístiques d'un craniu modernu, casi esféricu, cola bóveda alta y la frente vertical.[19] La semeyanza apreciar a nivel de la cadarma del cuerpu y cuévanu craneana, pero esta semeyanza nun ye total pos la cara entá caltien carauterístiques arcaiques como los arcos superciliares (grandes ceyes) y prognatismo maxilar (proyeición bucal), anque menos desenvueltos que nos neandertales.[20]

Considérense dientro d'esti grupu a los restos de Florisbad en Sudáfrica (260 000 años),[21] los d'Herto n'Etiopía, que correspuende a Homo sapiens idaltu (160 000 años), los de Jebel Irhoud en Marruecos (315 000 años) y los de Skhul/Qafzeh al Norte d'Israel (100 000 años). Tamién se consideren anatómicamente modernos a los homes de Kibish, sicasí estos enmárquense meyor dientro de los humanos modernos.

Considérense Homo sapiens sapiens de forma indiscutible a los que tienen les carauterístiques principales que definen a los humanos modernos: primero la equiparación anatómica coles poblaciones humanes actuales y depués lo que se define como "comportamientu modernu".

Anguaño, gracies a los analises científicos, sábese que na xenealoxía de la evolución humana esistiría un antepasáu común masculín y unu femenín; a los cualos nomóse-yos como los sos símiles relixosos.

Los restos más antiguos son los d'Omo I, llamaos Homes de Kibish, atopaos n'Etiopía con 195 000 años, y restos en cueves del ríu Klasies en Sudáfrica con 125 000 años y con nicios d'una conducta más moderna.[22]

Esta antigüedá coincide colo envalorao pa la Eva mitocondrial, que ta considerada l'antecesora de tolos seres humanos actuales y de la que se cree que vivió nel África Oriental[23] (probablemente Tanzania) fai unos 200 000 años.

Per otra parte, la llinia patrilineal llévanos hasta'l Adán cromosómico, quien nos confirma un orixe pa los humanos modernos nel África subsahariana y calcúlase-y unos 140 000 años d'antigüedá.[24]

Ye casi seguro que la Eva mitocondrial y l'Adán, los primeres Homo sapiens yeren melanodérmicos, esto ye, de tez escura. Esto debe a que la piel escuro ye una escelente adaptación a la esposición solar alta de les zones intertropicales del planeta Tierra; la tez escura (pola melanina) protexe de les radiaciones UV (ultravioletas) y llogra d'elles por metabolismu un nutriente llamáu folato, indispensable pal desenvolvimientu del embrión y del fetu; pero, a midida que les poblaciones humanes migraron a llatitúes más allá de los 45º (tantu Norte como Sur) la melanina pasu ente pasu foi menos necesaria, entá más, nes cercaníes de les llatitúes de los 50º la casi total falta d'esti pigmentu na dermis, pelo y güeyos foi una adaptación pa captar más radiaciones O.V. —relativamente escases en tales llatitúes, sacantes se produzan buecos d'ozonu—; en tales llatitúes la tez bien clara fai posible una mayor metabolización de vitamina D a partir de les radiaciones UV.

L'apaición del comportamientu humanu modernu significó'l más importante cambéu na evolución de la mente humana, dando llugar a que l'inxeniu creativu humanu llevaríalu a apoderar la so redolada pasu ente pasu. Una revolución humana que nos fixo como somos güei.

Les innovaciones que fueron apaeciendo consisten nuna gran diversidá de ferramientes de piedra, nel usu de güesu, estil y marfil, n'entierros con bienes funerarios y rituales, construcción de viviendes, diseñu de les fogatas, evidencia de pesca, cacería complexa, apaición del arte figurativu y l'usu d'adornos personales.[25]

Les evidencies más antigües atopar n'África; ferramientes ellaboraes fai 165 000 años atopar na cueva de Pinnacle Point (Sudáfrica).[26] Restos de puntes de fleches y ferramientes de güesu pa pescar atopar nel Congo y tienen 90 000 años. Igualmente antiguos son unos símbolos avisiegos con ocre coloráu en mariñes al sur d'África.[27]

Según la teoría fora d'África, hubo una gran migración d'África escontra Eurasia fai 70 000 años que produció la paulatina dispersión por tolos continentes. Según los estudios xenéticos y los descubrimientos paleontolóxicos, envalórase que fai 60 000 años hubo una migración costera pol Sur d'Asia, de pocos miles d'años, que fixo posible la colonización posterior d'Australia, Estremu Oriente y Europa.

N'Occidente hubo un centru d'espansión nel Mediu Oriente que ta rellacionáu col home de Cromañón y la población temprana d'Europa; probable causa de la estinción del home de Neandertal.

Según dellos estudios xenéticos, n'Europa hubo tres migraciones: la primera, proveniente del Asia Central fai 40 000 años que colonizó la Europa del Este. Una segunda folada fai 22 000 años, proveniente del Oriente Mediu, que s'instaló na Europa del sur y del oeste. El 80 % de los europeos actuales son descendientes d'estos dos migraciones, que mientres l'intre del máximu glaciar de fai 20 000 años, abelugar na Península Ibérica y nos Balcanes, pa volver espandise pol restu d'Europa cuando llegó'l clima favorable. La tercer migración produciríase fai 9000 años, proveniente del Oriente Mediu, mientres l'intre del Neolíticu y namái el 20 % de los europeos actuales lleven marcadores xenéticos correspondientes a esos emigrantes.[30]

Sicasí otros estudios dicen lo contrario, afirmando que n'Europa el componente neolíticu dende'l Cercanu Oriente ye'l más importante.[31] Lo cierto dica agora ye que'l mancomún xenéticu européu prehistóricu provien mayoritariamente del Cercanu Oriente, y una menor parte provien d'África, Asia Central y Siberia.

N'Oriente la población ye igualmente antigua. La plega epicántico de los párpagos esistente en gran parte de les poblaciones del Asia y d'América, la plega que fai 'bridados' nel so aspeutu esternu a los güeyos, foi una especialización de poblaciones que mientres les glaciaciones debieron pervivir en llugares con bayura de nieve; los güeyos vulgarmente llamaos «resgones» entós fueron la manera d'adaptación por que los güeyos nun carecieren un escesivu reflexu de la lluz solar reflexada pola nieve.[ensin referencies]

El llinguaxe designa toles comunicaciones basaes na interpretación, incluyendo'l llinguaxe humanu, pero la mayoría de les vegaes el términu referir a lo que los humanos utilicen pa comunicase, esto ye, a les llingües naturales. El llinguaxe ye universal y ye usáu por naturaleza nes persones y nos animales. Sicasí, filósofos como Martin Heidegger consideren que'l llinguaxe puramente tal ye namái privativu del home. Ye famosa la tesis de Heidegger según la cual el llinguaxe ye la casa del ser (Haus des Seins) y la morada de la esencia humana. Esti criteriu ye similar al d'Ernst Cassirer quien definió al Homo sapiens como'l animal simbólicu por excelencia; tan ye asina que ye casi imposible suponer un pensamientu humanu ensin l'ayuda de los símbolos, particularmente de los significantes que subyacen como fundamentos elementales pa tou pensar complexu y que transcienda a lo instintivo.

Anguaño la especie humana amuesa esta faceta falando en redol a 6000 idiomas distintos, magar más del 50 % de los 7000 millones de persones qu'anguaño conforma la coleutividá humana, sabe falar siquier una de les siguientes ocho llingües: chinu mandarín, español, inglés, árabe, hindi, portugués, bengalí o rusu.

En munches civilizaciones los seres humanos viéronse a sigo mesmos como distintos de los demás animales, y en ciertos ámbitos culturales (como les relixones del Llibru o bona parte de la metafísica del Occidente) la diferencia asignar a una entidá inmaterial llamada alma, na que moraríen la mente y la personalidá, y que dalgunos creen que puede esistir con independencia del cuerpu.

Posiblemente, la manifestación más clara d'humanidá ye l'arte —nel sentíu ampliu del términu—, que produz la cultura. Por casu, los individuos d'una determinada especie d'ave fabriquen un nial, o emiten un cantar, que les sos carauterístiques son específiques, comunes a tolos individuos d'esa especie. Sicasí, cada home puede imprimir a les sos aiciones les traces propies de la so individualidá; por eso, cuando s'analiza un cuadru, una forma d'escribir, una manera de fabricar ferramientes, etc., puede deducise quién ye'l so autor, el so artífiz, el so artista.[ensin referencies]

N'añu 2011, na revista Science, publicóse un trabayu de Francesco d'Errico, de la Universidá de Burdeos en Francia, onde afirmen haber atopáu unu de los rastros más antiguos d'un taller de pintura, na cueva Blombos en Cape Coast, 300 km al este de Ciudá del Cabu, esti fechu amuesa una manera sistemática pa llograr pigmentos, pos axuntar tolos elementos necesarios pa una preparación d'esti tipu, ye indicativu d'un eleváu nivel de pensamientu, que puede llamase pensamientu simbólicu. "La capacidá de tener estos pensamientos ye consideráu una reblagada na evolución humanes precisamente lo que nos estremó del mundu animal".[32]

Paralelamente, tamién somos la única especie que dedica'l so tiempu y enerxía a daqué aparentemente inútil dende'l puntu de vista puramente prácticu. L'arte ye una de les manifestaciones de la creatividá humana, pero una manifestación vacida y negativa dende'l puntu de vista de la supervivencia. Magar, esta actividá en principiu dañible, en realidá ye la ferramienta cola cual desenvolvemos la nuesa cultura, la nuesa unión, y la nuesa fuercia como pueblu. Estrémanos y dixebra d'unos pueblos; y hermánanos con otros. Nesta telaraña qu'envolubra a les nueses sociedaes, al nuesu planeta.[ensin referencies]

Una sociedá humana ye aquella que se considera a sigo mesma, a los habitantes y a la so redolada; tou ello interrelacionáu con un proyeutu común, que-yos da una identidá de pertenencia. Coles mesmes, el términu connota un grupu con llazos económicos, ideolóxicos y políticos. Tal sociedá supera al conceutu de nación tao, plantegando a la sociedá occidental como una sociedá de naciones, etc.

En rellación cola capacidá pa realizar grandes cambeos ambientales, cabo dicir que Homo sapiens ye anguaño un poderosu axente xeomorfolóxicu; ye n'este y otros sentíos en que'l ser humanu ye anguaño'l mayor superpredador y l'especie más poderosa del planeta, en comparanza colos demás especies. Sicasí, sigue siendo fráxil ante posible eventos cataclísmicos que pudieren afectar el so hábitat, como les glaciaciones.

Homo sapiens, por ser un animal bien vulnerable n'estáu de naturaleza, ye bien dependiente de la teunoloxía (ergo: ye dependiente de la ciencia por primitiva qu'esta sía), asina ye que dizse de Homo sapiens que ye homo faber.

Quiciabes, yá que tou sistema retroalimentáu de forma natural llega al so fin, el fin d'un ecosistema llega cuando la vida llogró evolucionar hasta llograr seres con un grau de conciencia capaz de programase en función de la educación recibida y non según lo termodinámicamente sostenible.[ensin referencies] La educación ye, poro, la demostración evidente de si somos parte d'un sistema entá mayor o intentamos independizanos de too, estableciendo les nueses formes de llograr los nuesos recursos, ensin tener en cuenta los yá establecíos pola mesma naturaleza.

Por casu, la naturaleza dóta-y de capacidaes físiques pa buscar alimentos nel mediu que los arrodia d'una manera termodinámicamente eficaz. Los humanos establecen que lo meyor ye racionalizar los medios que la naturaleza dalos y retrucar de forma industrial, aplicando procesos que nun se dan de forma natural, aumentando'l consumu enerxéticu por redundar daqué que yá esiste y ampliándolo a daqué totalmente termodinámicamente innecesariu, como ye'l fechu de que se-y apurra alimentu en casa, d'intervenir los códigos xenéticos de los alimentos pa faelos resistentes a enfermedaes, d'influyir en qué alimentos van contener granes y cuálos non y un llargu etcétera, qu'a día de güei fainos la vida más cómoda, pero qu'ignoren cómo-yos afecten esos cambeos na so estructura xenética y, poro, si la so descendencia va portar carauterístiques fundamentales pa sobrevivir a un mediu natural o, otra manera, van nacer y van depender tan íntimamente del mediu artificial que cualquier cambéu a esi mediu -y incapacite de tal manera que provoque la so estinción.[ensin referencies]

Homo sapiens (del llatín, homo 'home' y sapiens 'sabiu') ye una especie del orde de los primates perteneciente a la familia de los homínidos. Tamién son conocíos so la denominación xenérica de «homes», anque esi términu ye ambiguu y úsase tamién pa referise a los individuos de sexu masculino ysobremanera, a los varones adultos. Los seres humanos tienen capacidaes mentales que-yos dexen inventar, aprender y utilizar estructures llingüístiques complexes, lóxicas, matemátiques, escritura, música, ciencia, y teunoloxía. Los humanos son animales sociales, capaces de concebir, tresmitir y aprender conceutos totalmente astractos.

Considérense Homo sapiens de forma indiscutible a los que tienen tantu les carauterístiques anatómica de les poblaciones humanes actuales como lo que se define como «comportamientu modernu». Los restos más antiguos de Homo sapiens atopar en Marruecos con 315 000 años. La evidencia más antigua de comportamientu modernu son les de Pinnacle Point (Sudáfrica) con 165 000 años.

Pertenez al xéneru Homo que foi más diversificáu y, mientres l'últimu millón y mediu d'años incluyía otres especies yá estinguíes. Dende la estinción del Homo neanderthalensis, fai 28 000 años, y del Homo floresiensis fai 12 000 años (debatible), el Homo sapiens ye la única especie conocida del xéneru Homo qu'entá perdura.

Hasta apocayá, la bioloxía utilizaba un nome trinomial —Homo sapiens sapiens— pa esta especie, pero más apocayá refugóse el nexu filoxenéticu ente'l neandertal y l'actual humanidá, polo que s'usa puramente'l nome binomial. Homo sapiens pertenez a un fonduxe de primates, los hominoideos. Anque'l descubrimientu de Homo sapiens idaltu en 2003 fadría necesariu volver al sistema trinomial, la posición taxonómica d'esti postreru ye entá incierta. Evolutivamente estremar n'África y de esi ancestru surdió la familia de la que formen parte los homínidos.

Filosóficamente, el ser humanu se definió y redefinió a sigo mesmu de numberoses maneres al traviés de la hestoria, otorgándose d'esta manera un propósitu positivu o negativu respectu de la so propia esistencia. Esisten diversos sistemes relixosos ya ideales filosóficos que, d'alcuerdu a una diversa gama de culturas ya ideales individuales, tienen como propósitu y función responder delles d'eses interrogantes esistenciales. Los seres humanos tienen la capacidá de ser conscientes de sigo mesmos, lo mesmo que d'el so pasáu; saben que tienen el poder d'entamar, tresformar y realizar proyeutos de diversos tipos. En función a esta capacidá, crearon diversos códigos morales y dogmas empobinaos direutamente al manexu d'estes capacidaes. Amás, pueden ser conscientes de responsabilidaes y peligros provenientes de la naturaleza, asina como d'otros seres humanos.

O fewn y dull enwi gwyddonol, Homo sapiens (Lladin: "person deallus") yw'r enw rhyngwladol ar fodau dynol, ac a dalfyrir yn aml yn H. sapiens. Bellach, gyda diflaniad y Neanderthal (ac eraill), dim ond y rhywogaeth hon sy'n bodoli heddiw o fewn y genws a elwir yn Homo. Isrywogaeth yw bodau dynol modern (neu bobl modern), a elwir yn wyddonol yn Homo sapiens sapiens.

Hynafiaid pobl heddiw, yn ôl llawer, oedd yr Homo sapiens idaltu. Credir fod eu dyfeisgarwch a'u gallu i addasu i amgylchfyd cyfnewidiol wedi arwain iddynt fod y rhywogaeth mwyaf dylanwadol ar wyneb Daear ac felly fe'i nodir fel "pryder lleiaf" ar Restr Goch yr IUCN, sef y rhestr o rywogaethau mewn perygl o beidio a bodoli, a gaiff ei gynnal gan Yr Undeb Ryngwladol Dros Cadwraeth Natur.[1]

Y Naturiaethwr Carl Linnaeus a fathodd yr enw, a hynny 1758.[2] Yr enw Lladin yw homō (enw genidol hominis) sef "dyn, bod dynol" ac ystyr sapien yw 'deallus'.

Gyda thystiolaeth newydd yn cael ei darganfod yn flynyddol, bron, mae rhoi dyddiad ar darddiad y rhywogaeth H. sapiens yn beth anodd; felly hefyd gyda dosbarthiad llawer o esgyrn gwahanol isrywogaethau, a cheir cryn anghytundeb yn y byd gwyddonol wrth i fwy a mwy o esgyrn ddod i'r golwg. Er enghraifft, yn Hydref 2015, yn y cylchgrawn Nature cyhoeddwyd i 47 o ddannedd gael eu darganfod yn Ogof Fuyan yn Tsieina a ddyddiwyd i fod rhwng 80,000 a 125,000 o flynyddoedd oed.

Yn draddodiadol, ceir dau farn am ddechreuad H. sapiens. Mae'r cynta'n dal mai o Affrica maent yn tarddu, a'r ail farn yn honni iddynt darddu o wahanol lefydd ar yr un pryd.

Ceir sawl term am y cysyniad 'Allan-o-Affrica' gan gynnwys recent single-origin hypothesis (RSOH) a Recent African Origin (RAO). Cyhoeddwyd y cysyniad hwn yn gyntaf gan Charles Darwin yn ei lyfr Descent of Man yn 1871 ond nid enillodd ei blwyf tan y 1980au pan ddaeth tystiolaeth newydd i'r fei: sef astudiaeth o DNA ac astudiaeth o siap ffisegol hen esgyrn. Oherwydd gwydnwch y dannedd, dyma'n aml yr unig dystiolaeth sy'n parhau oherwydd fod gweddill y corff wedi pydru. Gan ddefnyddio'r ddwy dechneg yma i ddyddio Homo sapiens, credir iddynt darddu o Affrica rhwng 200,000 a 125,000 o flynyddoedd yn ôl. Llwyddodd H. sapiens i wladychu talpiau eang o'r Dwyrain, ond methwyd yn Ewrop oherwydd fod yno gynifer o Neanderthaliaid yn ffynnu'n llwyddiannus. O astudio'r genynnau, credir yn gyffredinol i H. sapiens baru gyda Neanderthaliaid.

Erbyn 2015 dyma'r farn fwyaf cyffredin.[3][4] Yn 2017 mynnodd Jean-Jacques Hublin o Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology yn Leipzig fod ffosiliau o Moroco'n profi i H. Sapiens wahanu 350,000 CP.[5]

Yr ail farn (a gynigiwyd gan Milford H. Wolpoff yn 1988) yw i H. sapiens darddu ar ddechrau'r Pleistosen, 2.5 miliwn o flynyddoedd CP gan esbylgu mewn llinell syth hyd at ddyn modern (yr Homo sapiens sapiens) - hynny yw heb iddo baru gyda Neanderthaliaid.

O fewn y dull enwi gwyddonol, Homo sapiens (Lladin: "person deallus") yw'r enw rhyngwladol ar fodau dynol, ac a dalfyrir yn aml yn H. sapiens. Bellach, gyda diflaniad y Neanderthal (ac eraill), dim ond y rhywogaeth hon sy'n bodoli heddiw o fewn y genws a elwir yn Homo. Isrywogaeth yw bodau dynol modern (neu bobl modern), a elwir yn wyddonol yn Homo sapiens sapiens.

Hynafiaid pobl heddiw, yn ôl llawer, oedd yr Homo sapiens idaltu. Credir fod eu dyfeisgarwch a'u gallu i addasu i amgylchfyd cyfnewidiol wedi arwain iddynt fod y rhywogaeth mwyaf dylanwadol ar wyneb Daear ac felly fe'i nodir fel "pryder lleiaf" ar Restr Goch yr IUCN, sef y rhestr o rywogaethau mewn perygl o beidio a bodoli, a gaiff ei gynnal gan Yr Undeb Ryngwladol Dros Cadwraeth Natur.

Der Mensch (Homo sapiens, lateinisch für „verstehender, verständiger“ oder „weiser, gescheiter, kluger, vernünftiger Mensch“) ist nach der biologischen Systematik eine Art der Gattung Homo aus der Familie der Menschenaffen, die zur Ordnung der Primaten und damit zu den höheren Säugetieren gehört. Allgemeine Eigenschaften der Menschen und besondere Formen menschlichen Zusammenlebens werden in der Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Soziologie untersucht.

Im Laufe der Stammesgeschichte des Menschen, der Hominisation und der soziokulturellen Evolution haben sich Merkmale herausgebildet, welche die Voraussetzungen dafür bildeten, dass der Mensch ein in hohem Maße sozialisations- und kulturabhängiges Wesen werden konnte. Dazu gehören eine lang andauernde Kindheit, die Fähigkeit zum Spracherwerb und zu gemeinschaftlicher Arbeit sowie das Eingehen besonders komplexer sozialer Bindungen.

Durch ihr Bewusstsein erschließt sich den Menschen die zeitliche Dimension des Daseins sowie ein reflektiertes Verhältnis zu sich selbst. Daraus ergeben sich die eigene Existenz betreffende Fragen, wie zum Beispiel die nach der persönlichen Freiheit, nach der menschlichen Stellung in der Natur, nach moralischen Grundsätzen des Zusammenlebens und einem Sinn des Lebens. Im Rahmen der Reflexion des Verhältnisses zu anderen Lebewesen haben viele Kulturen im Laufe der bisherigen Geschichte der Menschheit ein Menschenbild entwickelt, das die Menschheit von der Tierwelt absondert und dieser gegenüberstellt. Eine solche Sonderstellung wurde etwa durch Schöpfungserzählungen begründet, die den Menschen einen separaten Ursprung zuschreiben, oder durch die Bestimmung des Menschen als Vernunftwesen. Sie findet aber auch in modernen Vorstellungen wie der der Menschenwürde einen Widerhall.

Der Mensch ist die einzige rezente Art der Gattung Homo. Er ist in Afrika seit rund 300.000 Jahren fossil belegt[1] und entwickelte sich dort über ein als archaischer Homo sapiens bezeichnetes evolutionäres Bindeglied vermutlich aus Homo erectus. Zwischen Homo sapiens, den Neandertalern und den Denisova-Menschen gab es nachweislich – vermutlich mehrfach – einen Genfluss. Weitere, jedoch deutlich jüngere fossile Belege, gibt es für die Art von allen Kontinenten, außer Antarktika. Von den noch lebenden Menschenaffen sind die Schimpansen dem Menschen stammesgeschichtlich am nächsten verwandt, vor den Gorillas. Der Mensch hat eine kosmopolitische Verbreitung.

Die Weltbevölkerung des Menschen umfasste zur Mitte des Jahres 2021 rund 7,875 Milliarden Individuen.[2] Die Entwicklung technologischer Zivilisation führte zu einem umfassenden anthropogenen Einfluss auf die Umwelt (fortschreitende Hemerobie), so dass vorgeschlagen wurde, das aktuelle Erdzeitalter Anthropozän zu nennen.

Das Wort Mensch ist im Althochdeutschen seit dem 8. Jahrhundert in der Schreibung mennisco (Maskulinum) belegt und im Mittelhochdeutschen in der Schreibung mensch(e) (Maskulinum oder Neutrum) in der Bedeutung „Mensch“. Das Wort ist eine Substantivierung von althochdeutsch mennisc, mittelhochdeutsch mennisch für „mannhaft“ und wird zurückgeführt auf einen indogermanischen Wortstamm, in dem die Bedeutung Mann und Mensch in eins fiel – heute noch erhalten in man. Das Neutrum (das Mensch) hatte bis ins 17. Jahrhundert keinen abfälligen Beiklang und bezeichnete bis dahin insbesondere Frauen von niederem gesellschaftlichen Rang.[3]

Der Name der Art Homo sapiens (klassisch [ˈhɔmoː ˈsapieːns], gebräuchliche Aussprache [ˈhoːmo ˈzaːpiəns], nach lat. homo sapiens ‚einsichtsfähiger/weiser Mensch‘) wurde 1758 durch Carl von Linné in der zehnten Auflage seines Werks Systema Naturae geprägt. Auch im aktuellen Catalog of Life des Integrated Taxonomic Information System wird die Bezeichnung „Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758“ als „akzeptierter wissenschaftlicher Name“ ausgewiesen.[4] Von den 1930er-Jahren bis in die 1990er-Jahre wurde der moderne Mensch als Homo sapiens sapiens und der Neandertaler als Homo sapiens neanderthalensis bezeichnet. Diese Einordnung des Neandertalers als Unterart von Homo sapiens gilt jedoch derzeit als veraltet, da es seitdem unter Paläoanthropologen „eine zunehmende Akzeptanz, dass die Neandertaler morphologisch unverwechselbar sind,“ gibt und sich daher in der Fachliteratur die Bezeichnungen Homo sapiens und Homo neanderthalensis durchgesetzt haben.[5]

Mit dem Körper des Menschen befassen sich unter anderem die Anatomie, die Humanbiologie und die Medizin. Die Anzahl der Knochen des Menschen beträgt (individuell verschieden) beim Erwachsenen 206 bis 214. Das Skelett von Säuglingen hat noch mehr als 300 Knochen, von denen einige im Laufe der Zeit zusammenwachsen.

Die Körpergröße des Menschen ist zum Teil vererbt, hängt jedoch auch von Lebensumständen wie der Ernährung ab. Auch das Geschlecht spielt eine Rolle: Männer sind im Durchschnitt größer als Frauen. Seit dem 19. Jahrhundert ist die durchschnittliche Körpergröße in Mitteleuropa bzw. Deutschland von 167,6 cm (Männer) / 155,7 cm (Frauen)[6] auf 178 cm (Männer) / 165 cm (Frauen)[7] angestiegen.

Für das Körpergewicht des Menschen gibt es keinen medizinischen Konsens, was als „wünschenswert“ oder „natürlich“ gelten sollte, zumal das Körpergewicht auch von der Körpergröße abhängig ist. Gleichwohl hat die Weltgesundheitsorganisation (WHO) hilfsweise anhand des Body-Mass-Index (BMI) einen Normbereich (normal range) definiert, der einen BMI von 18,50 bis 24,99 umfasst.[8]

Im Folgenden werden einige der wichtigsten Merkmale der Spezies, insbesondere im Vergleich zu anderen Menschenaffen und sonstigen Primaten, genannt.

Der Mensch besitzt einen aufrechten Gang (Bipedie), was in der Tierwelt an sich nichts Ungewöhnliches, jedoch bei den Säugetieren selten ist. Der aufrechte Gang ermöglicht dem Menschen das zweibeinige Stehen, Gehen, Laufen. Er hat damit zwei Gangarten. Gerade im Säuglingsalter hat er aber noch ein großes Repertoire weiterer Bewegungsabläufe (krabbeln) und kann auch eigene entwickeln (z. B. Hopserlauf).

Der Mensch besitzt keinen Greiffuß wie die meisten anderen Primaten, sondern einen Fuß mit verkürzten Zehen und anliegender Großzehe. Dafür dient die Hand des Menschen nicht mehr zur Fortbewegung. Untypisch für einen Affen sind beim Menschen die Arme kürzer als die Beine. Wie bei allen Menschenartigen fehlt der Schwanz. Eine weitere Folge der Entwicklung des aufrechten Gangs beim Menschen ist seine doppelt-S-förmige Wirbelsäule und das kräftig ausgebildete Gesäß, welches die aufrechte Haltung und Fortbewegung erst ermöglicht.

Der aufrechte Gang muss erst individuell erlernt werden, was etwa ein bis eineinhalb Jahre ab der Geburt dauert.

Das menschliche Gehirn entspricht in seinem Aufbau dem Gehirn anderer Primaten, ist jedoch im Verhältnis zur Körpergröße größer.[9][10] Die Anzahl der Nervenzellen im Gehirn eines erwachsenen Menschen beträgt etwa 86 Milliarden, in der Rinde des Großhirns etwa 16 Milliarden.[10][11] Im Vergleich dazu hat das Gehirn eines Rhesusaffen ca. 6,4 Milliarden Nervenzellen[12] und das Gehirn eines Elefanten ca. 257 Milliarden, davon 5,6 Milliarden in der Großhirnrinde (Cortex cerebri).[13] Doch beim Grindwal beträgt die Neuronenanzahl allein im Neocortex ca. 37 Milliarden, also etwa doppelt so viel wie beim Menschen.[14]

Was am menschlichen Gehirn besonders stark ausgeprägt ist, ist die Großhirnrinde, insbesondere die Frontallappen, denen exekutive Funktionen wie Impulskontrolle, emotionale Regulation, Aufmerksamkeitssteuerung, zielgerichtetes Initiieren und Sequenzieren von Handlungen, motorische Steuerung, Beobachtung der Handlungsergebnisse und Selbstkorrektur zugeordnet werden. Der Bereich der Großhirnrinde, der für das Sehen zuständig ist, sowie Zonen, die für die Sprache eine Rolle spielen, sind ebenfalls beim Menschen deutlich vergrößert.

Anhand von Fossilienfunden ist belegbar, dass sich der aufrechte zweibeinige Gang des Menschen deutlich früher entwickelte als die starke Vergrößerung des Gehirns.[15] Die Vergrößerung des Gehirns ereignete sich zeitgleich mit einer Verkleinerung der Kaumuskulatur.

Das Gesicht des Menschen ist flacher als bei einem Menschenaffen-Schädel, der eine hervorstehende Schnauze hat. Hingegen hat der Mensch durch die Rücknahme des Ober- und Unterkiefers ein vorspringendes Kinn. Mit der starken Zunahme des Gehirnvolumens entstand eine hohe Stirn und seine charakteristische Schädelform.

Der Mensch verfügt in besonderem Maße über die Fähigkeit der Wärmeabfuhr durch Schwitzen. Kein anderer Primat besitzt eine so hohe Dichte an Schweißdrüsen wie der Mensch. Die Kühlung des Körpers durch Schwitzen wird unterstützt durch die Eigenheit, dass der Mensch im Unterschied zu den meisten Säugetieren kein (dichtes) Fell hat. Während seine Körperbehaarung nur gering ausgebildet ist, wächst sein Kopfhaar ohne natürlich begrenzte Länge. Ein Teil der verbliebenen Körperbehaarung entwickelt sich erst in der Pubertät: das Scham- und Achselhaar, sowie Brust- und Barthaar beim Mann.

Eine Folge der Felllosigkeit ist die rasche Auskühlung bei Kälte aufgrund der geringeren Wärmeisolation. Der Mensch lernte jedoch, dies durch das Nutzen von Feuer und das Anfertigen von Behausungen und Kleidung zu kompensieren. Beides ermöglicht ihm auch das Überleben in kälteren Regionen. Ein weiterer Nachteil der Felllosigkeit ist das erhöhte Risiko für die Haut, durch ultraviolettes Licht geschädigt zu werden, da Fell einen wichtigen Sonnenschutz darstellt. Die je nach Herkunftsregion unterschiedliche Hautfarbe wird als Anpassung an die – je nach geographischer Breite – unterschiedlich intensive Einstrahlung des von der Sonne kommenden ultravioletten Lichts interpretiert (→ Evolution der Hautfarben beim Menschen).

Nach heutigem Kenntnisstand ist der moderne Mensch „von Natur aus“ weder ein reiner Fleischfresser (Carnivore) noch ein reiner Pflanzenfresser (Herbivore), sondern ein so genannter Allesfresser (Omnivore); umstritten ist allerdings, welcher Anteil der Nahrungsaufnahme in den verschiedenen Zeiten und Regionen auf Fleisch und auf Pflanzenkost entfiel.[16] Die omnivore Lebensweise erleichterte es dem modernen Menschen, sich nahezu jedes Ökosystem der Erde als Lebensraum zu erschließen.[17]

Der Mensch besitzt ein Allesfressergebiss mit parabelförmig angeordneten Zahnreihen. Wie die meisten Säugetiere vollzieht er einen Zahnwechsel. Das Milchgebiss des Menschen hat 20 Zähne, das bleibende Gebiss 32 (inklusive Weisheitszähne). Die Zahnformel des Menschen ist wie bei allen Altweltaffen I2-C1-P2-M3. Der Mensch hat jedoch verkleinerte Schneide- und Eckzähne.

Die Fruchtbarkeit (die Geschlechtsreife mit dem Erreichen der Menarche bzw. Spermarche) beginnt beim Menschen deutlich später als bei anderen (auch langlebigen) Primaten.

Eine Besonderheit der menschlichen Sexualität ist der versteckte Eisprung. Während die Fruchtbarkeit bei weiblichen Säugetieren in der Regel durch körperliche oder Verhaltens-Signale mitgeteilt wird, damit in dieser Phase eine Befruchtung stattfinden kann, ist sie beim Menschen „versteckt“. Deshalb ist der Geschlechtsakt beim Menschen weniger stark mit der Fortpflanzung verbunden. Das Sexualverhalten des Menschen hat über die Rekombination von Genen hinaus zahlreiche soziale Funktionen; es gibt mehrere sexuelle Orientierungen.

Eine weitere Besonderheit ist die Menopause bei der Frau. Bei vielen Tierarten sind Männchen und Weibchen in aller Regel bis zu ihrem Tode fruchtbar. Nur bei wenigen Tierarten ist die Fruchtbarkeit des Weibchens zeitlich begrenzt.

Die Schwangerschaft, wie die Trächtigkeit beim Menschen genannt wird, beträgt von der Befruchtung bis zur Geburt durchschnittlich 266 Tage.[18]

Wegen des großen Gehirnvolumens des Menschen bei gleichzeitigen durch den aufrechten Gang bestimmten Anforderungen an seinen Beckenboden ist die Geburt besonders problematisch: Eine menschliche Geburt kann weit schmerzhafter sein als bei Tieren, auch im Vergleich mit anderen Primaten, und kann auch leichter zu Komplikationen führen. Um deren Auftreten zu verringern und bereits aufgetretene behandeln zu können, wurden die Methoden der Geburtshilfe entwickelt.

Neugeborene kommen in einem besonders unreifen und hilflosen Zustand auf die Welt. Die Säuglinge verfügen in den ersten Lebensmonaten lediglich über (Neugeborenen-)Reflexe. Sie können sich nicht eigenständig fortbewegen und sind daher weitgehend passive Traglinge.

Der Mensch zählt zu den langlebigsten Tieren und ist die langlebigste Spezies unter den Primaten.

Neben genetischen Anlagen spielen die Qualität der medizinischen Versorgung, Stress, Ernährung und Bewegung wichtige Rollen bei der menschlichen Lebenserwartung. Frauen haben im Durchschnitt eine um mehrere Jahre höhere Lebenserwartung als Männer. Die Lebenserwartung hat sich in den letzten Jahrzehnten in den meisten Ländern der Erde kontinuierlich verlängert. Unter guten Rahmenbedingungen können Menschen 100 Jahre und älter werden.

Bis in die späten 1980er-Jahre wurden die Orang-Utans, Gorillas und Schimpansen in der Familie der Menschenaffen (Pongidae) zusammengefasst und der Familie der Echten Menschen (Hominidae) gegenübergestellt. Genetische Vergleiche zeigten, dass Schimpansen und Gorillas näher mit dem Menschen verwandt sind als mit den Orang-Utans; seitdem werden Menschen, Schimpansen und Gorillas nebst all ihren fossilen Vorfahren zur Unterfamilie Homininae und diese neben das Taxon Ponginae der Orang-Utans gestellt.

Von den anderen heute noch lebenden Menschenaffen kann Homo sapiens anhand seines Genotyps unterschieden werden, ferner anhand seines Phänotyps, seiner Ontogenie und seines Verhaltens. Hinzu kommen erhebliche Unterschiede in Bezug auf die Dauer bestimmter Lebensabschnitte: die Entwicklung des Säuglings vollzieht sich bei Homo sapiens langsamer als bei den anderen Menschenaffen – mit der Folge, dass der Mensch eine deutlich verlängerte Kindheit sowie Adoleszenz besitzt. Dies wiederum hat zur Folge, dass der Mensch erst relativ spät geschlechtsreif wird und der Aufwand der Eltern zugunsten ihrer Kinder sehr hoch ist; zudem ist der Abstand zwischen den Geburten geringer und die Lebenserwartung höher.[19]

Vom 18. Jahrhundert bis zum späten 20. Jahrhundert wurde die Art Homo sapiens in verschiedene Rassen oder Varietäten unterteilt (siehe Rassentheorie). Dies erwies sich jedoch ab den 1970er-Jahren aufgrund populationsgenetischer Untersuchungen als fragwürdig und gilt heute als nicht mehr haltbar. Ende der 1920er-Jahre unternahm der russische Biologe und Tierzüchter Ilja Iwanowitsch Iwanow ergebnislose Kreuzungsversuche zwischen Schimpansen und Menschen.

Die Erbinformation des Menschen ist im Zellkern in der DNA auf 46 Chromosomen, davon zwei Geschlechtschromosomen, gespeichert sowie in der DNA der Mitochondrien. Das menschliche Genom wurde in den Jahren 1998 bis 2005 vollständig sequenziert. Insgesamt enthält das Genom diesem Befund zufolge rund 20.000 bis 25.000 Gene und 3,2 Millionen Basenpaare.[20][21]

Das menschliche Genom enthält (wie das jedes anderen Eukaryoten) sowohl codierende als auch nicht-codierende DNA-Sequenzen, die oftmals denjenigen verwandter Lebewesen homolog sind („gleiches“ Gen) und häufig mit den DNA-Sequenzen sehr nahe verwandter Arten – wie der anderer Menschenaffen – sogar völlig übereinstimmen. Aus der Ähnlichkeit der DNA-Sequenzen unterschiedlicher Arten lässt sich zudem deren Verwandtschaftsgrad berechnen: Auf diese Weise bestätigten genetische Analysen, dass die Schimpansenarten (Bonobos, Gemeine Schimpansen), Gorillas[22] und Orang-Utans (in dieser Reihenfolge) die nächsten rezenten Verwandten des Menschen sind.

Weitere genetische Analysen ergaben, dass die genetische Vielfalt beim Menschen, im Vergleich mit den anderen Menschenaffen, gering ist. Dieser Befund wird erklärt durch eine zeitweise sehr geringe (am Rande des Aussterbens befindliche) Population (vergleiche: Mitochondriale Eva, Adam des Y-Chromosoms).

Inzwischen wiesen mehrere Studien darauf hin, dass archaische Verwandte des anatomisch modernen Menschen in geringer Menge (1–2 %) Spuren im Genom von unterschiedlichen Populationen des modernen Menschen hinterlassen haben. Zunächst wurde das für den Neandertaler in Europa und Westasien nachgewiesen,[23][24] etwas später für den Denisova-Menschen in Südostasien[25][26] und zuletzt wurden solcher Genfluss archaischer Menschen zu Homo sapiens auch für Afrika postuliert.[27][28][29]

Als Carl von Linné 1735 den Menschen in seiner Schrift Systema Naturæ dem Tierreich und in diesem der Gattung Homo zuordnete, verzichtete Linné – im Unterschied zu seiner üblichen Vorgehensweise – auf eine Diagnose, das heißt auf eine an körperlichen Merkmalen ausgerichtete, genaue Beschreibung der Gattung. Stattdessen notierte er: Nosce te ipsum („Erkenne dich selbst“) und ging demnach davon aus, dass jeder Mensch genau wisse, was ein Mensch sei. Die Gattung Homo unterteilte er in vier Varianten: Europæus, Americanus, Asiaticus sowie Africanus und gab ihnen jeweils noch Farbmerkmale bei – albescens, rubescens, fuscus und nigrans, gleichbedeutend mit hell, rötlich, braun und schwarz. 1758, in der 10. Auflage von Systema Naturæ, bezeichnete Linné den Menschen zwar erstmals auch als Homo sapiens und führte zudem diverse angebliche charakterliche und körperliche Merkmale der Varianten an, verzichtete aber weiterhin auf eine Benennung der diagnostischen Merkmale der Art.

1775 bezeichnete Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in seiner Dissertation De generis humani varietate nativa („Über die natürlichen Verschiedenheiten im Menschengeschlechte“) die von Linné eingeführten Varianten als die vier „Varietäten“ des Menschen[30] und beschrieb einige ihrer gemeinsamen Merkmale. Diese Gemeinsamkeiten führte er – mehr als 80 Jahre vor Darwins Die Entstehung der Arten – darauf zurück, dass sie einer gemeinsamen „Gattung“ entsprungen seien. Jedoch erwiesen sich auch diese Merkmale nicht als geeignet, mit ihrer Hilfe zu entscheiden, ob Fossilien der Art Homo sapiens zuzuordnen oder nicht zuzuordnen sind.

Einen Schritt weiter ging der Botaniker William Thomas Stearn und erklärte 1959 Carl von Linné selbst (Linnaeus himself) zum Lectotypus der Art Homo sapiens.[31] Diese Festlegung ist nach den heute gültigen Regeln korrekt.[32] Carl von Linnés sterbliche Überreste (sein im Dom zu Uppsala bestattetes Skelett) sind daher der nomenklatorische Typus des anatomisch modernen Menschen.[33]

Dennoch fehlt auch weiterhin eine allgemein anerkannte Diagnose der Art Homo sapiens: „Unsere Art Homo sapiens war niemals Gegenstand einer formalen morphologischen Definition, die uns helfen würde, unsere Artgenossen in irgendeiner brauchbaren Weise in den dokumentierten fossilen Funden zu erkennen.“[34] Mangels klarer morphologischer Kriterien erfolgt die Zuordnung von Fossilien zu Homo sapiens häufig primär aufgrund ihres datierten Alters, eines bloßen paläontologischen Hilfskriteriums.

Die Entwicklung des Menschen führte vermutlich über Arten, die den nachfolgend aufgeführten Arten zumindest ähnlich gewesen sein dürften, zu Homo sapiens: Ardipithecus ramidus, Australopithecus afarensis, Homo rudolfensis / Homo habilis und Homo ergaster / Homo erectus.

315.000 Jahre alte Schädelknochen aus Marokko gelten derzeit als älteste, unbestritten dem anatomisch modernen Menschen zugeordnete Fossilien.[35] Lange Zeit lebte die Art Homo sapiens in Afrika parallel zum primär europäisch und vorderasiatisch angesiedelten Neandertaler, der besonders an das Leben in gemäßigten bis arktischen Zonen angepasst war.