pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

It is agreed upon that the species is native to Europe since numerous sightings and specimens have been recorded in almost twenty three countries of the continent. It was also recorded to be seen widespread in parts of the northern United States and Canada.

Psilocybe semilanceata is a small thin saprotrophic mushroom and is one of more than one hundred and eighty species of mushrooms under the genus Psilocybe. Psilocybe semilanceata is significant because it contains the psychoactive compound Psilocybin and baeocystin which, when consumed, causes feelings of euphoria, hallucinations and dissociation. Psilocybe semilanceata is widely distributed across the world including the vast majority of Europe and parts of North America. Currently much of the world has penalties for individuals possessing Psilocybe semilanceata mushrooms and the United States has labeled it as a Schedule I substance.

Psilocybe semilanceata obtains its nutrients from breaking down dead plant and other organic matter. This process of obtaining nutrition is considered saprotrophic[1]. A study done by a group of scientists in 1990 showed that that the mushroom grows solitarily or in groups on the ground, typically in fields and pastures[1]. It is often found in fields that have been fertilized with sheep or cow dung, even though it does not typically grow directly on the dung[1]. The mushroom is also associated with sedges in moist areas of fields and is often growing on dead organic plant matter[2].

This species was first described in 1838 by the great Swedish mycologist Elias Magnus Fries, who named it Agaricus semilanceata. (Most of the gilled mushrooms were included initially in the genus Agaricus!) In 1871 German mycologist Paul Kummer transferred this species to the genus Psilocybe, renaming it Psilocybe semilanceata [1]. Much of this mushroom’s phylogeny became resolved in the coming of the twenty first century. Much of the studies done in the early 2000s, such as the study done by Jean-Marc Moncalvo, supported the idea of dividing the genus into two clades, one consisting of the bluing, hallucinogenic species in the family Hymenogastraceae, and the other the non-bluing, non-hallucinogenic species in the family Strophariaceae making the species polyphyletic[2]. Much of its closest relatives belong to the genus Psilocybe including the famous, Psilocybe cubensis.

The etymology of this name is based on physical features: the generic name Psilocybe means 'smooth head', while semilanceata means 'half spear-shaped'. Panaeolus semilanceata, named by Jakob Emanuel Lange in both 1936 and 1939 publications, is a synonym.

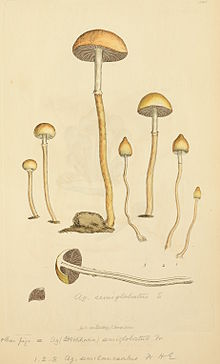

Psilocybe semilanceata is a small mushroom that grows between 1.5 inches (4 cm) and 4 inches (10 cm) tall with a tiny mushroom cap between 1/5 of an inch (5 mm) to 1 inch (25 mm) wide. The Pileus or cap is usually 0.5-2.5 cm broad. It is often, incurved and sometimes wavy or undulated in young fruiting bodies, often darkened by spores. Its surface is smooth, color variable, and extremely hygrophanous meaning a color change in the mushroom tissue. It is usually dark chestnut brown when moist, soon drying to a light tan or yellow, occasionally with an olive tint, margin sometimes with bluish or olive stains. Surface viscid or sticky when moist from a separable gelatinous membrane called the pellicle. The Gills are usually found as mostly narrowly attached to the stipe (adnexed), it does sometimes become adnate or seceding. The gills are also close to crowded and narrow and their color is pale at first, rapidly becoming grey, then brownish and finally purplish brown with the edges remaining pale. The stem is long and slender flexuous (curved or sinuous), and pliant. Psilocybe semilanceata pale to more brownish towards the base, where the attached mycelium may become bluish tinged, especially during drying. Surface smooth overall. The context stuffed with a spongy fibrous tissue called a pith. There is a partial veil thinly coordinate, rapidly deteriorating, leaving an obscure evanescent annular zone of fibrils, usually darkened by spores. The spores are dark purplish brown in deposit, ellipsoid, 11-14 by 7-9 microns.

Several reports have been published in the literature documenting the effects of consumption of Psilocybe semilanceata and other mushroom species belonging to the genus Psilocybe. Typical symptoms include visual distortions of color, depth and form, progressing to visual hallucinations. The effects are similar to the experience following consumption of Lysergic Acid Diethylamine(LSD), although milder[1]. Time magazine wrote about new evidence found that shows how Psilocybin works and why it holds promise as a treatment for depression and other such mental illness. Robin Carhart-Harris, a postdoctoral student at Imperial College London and lead author of the study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences had this to say. “The results seem to imply that a lot of brain activity is actually dedicated to keeping the world very stable and ordinary and familiar and unsurprising[2].” Throughout history, ancient pictures, carving, and statues have been seen, showing the importance of the genus Psilocybe to ancient tribes.

In the United States, any mushroom containing psilocybin including Psilocybe semilanceata is a Schedule I drug under an amendment to the Controlled Substances Act called the Psychotropic Substances Act. This means that it has a high potential for abuse, has no currently accepted medical use and isn't safe for use even under a doctor's supervision. However, it is completely legal to posses the spores since they do not contain psilocybin.

Throughout history, ancient pictures, carving, and statues have been seen, showing the importance of the genus Psilocybe to ancient tribes. In Central and South America, use of Psilocybin containing mushrooms was a common religious practice until the arrival of Spanish settlers, who were intent on spreading the Catholic faith, strictly prohibited their use. For Indians the fungi are known as sacred mushroom and historically, it is considered entheogen, propelling them on a religious path to the spirit world.

La bruixa aguda (Psilocybe semilanceata) pertany a un gènere de bolets menuts que creixen pertot arreu. Aquest gènere és molt ben conegut per les seues propietats al·lucinògenes, conegut també com a "bolets màgics", encara que la majoria d'espècies del gènere no contenen alcaloides al·lucinògens. La psilocina i la psilocibina són els composts al·lucinògens responables dels efectes psicoactius de moltes espècies del gènere.

Psilocybe semilanceata: bongui, mongui, sorgin zorrotz.

El gènere pot tenir altres noms com: bolets màgics, bolets sagrats, liberty caps (EUA: barrets de la llibertat), teonanacatl (Mèxic: carn de deu), nti-si-tho (mazatecs: que germina), bolets dels somnis, bolets al·lucinògens.

El culte als bolets màgics prové de l'època precolombina. Van ser les expedicions espanyoles del segle XVI, les quals trobaren les primeres indicacions sobre l'ús d'aquests per les tribus índies de Mèxic meridional, sobretot a les regions zapotèque, nahuatl i otomi.

Bernardino de Sahagún, Motolinia, Francisco Hernández, Jacinto de la Serna havien remarcat el poder narcòtic i embriagant dels teonanacatl.

Es van descobrir estàtues de pedra, amb formes de bolets, a Guatemala, El Salvador i a Mèxic meridional, les quals poden ser del període que va entre 2000 aC i el 900 de l'era cristiana. Aquestes figures estan formades per un barret hemisfèric amb forma de Psilocybe, i un peu robust amb una esfinx humana o animal. Eren emprades en cerimònies consagrades en què consumien els bolets al·lucinògens.

Fou R. Wasson, qui després d'haver-hi assistit a una cerimònia, inicia l'estudi dels bolets màgics. L'experiència viscuda la narra a l'article "En busca del hongo mágico". El seu col·laborador Robert Heim aconsegueix cultivar amb èxit exemplars de Psilocybe. I Albert Hoffman, descobridor del LSD, aïlla i sintetitza els alcaloides indólics, psilocibina y psilocina, responsables dels efectes psicoactius dels bolets mexicans.

Actualment se sap que s'han emprat pràcticament a tot el món (Índia, Algèria, Europa medieval) per la presència en motius artístics.

La família de les Estroforiàcies té espècies de colors generalment marró o avellana, amb làmines adherents, esporada marró fosca amb porós germinatiu.

Psilocibe: Espècies petites, amb barret cònic o acampanulat, làmines no separables i peu bastant llarg i prim, que pot presentar o no un anell. Les espècies al·lucinògenes poden identificar-se pel fet que el seu peu es tenyeix de blau quan es rasca.

Psilocibe semilanceata:

A Espanya és abundant en la Sierra de Guadarrama, País Basc, Navarra, Catalunya. Creix de forma dispersa i en grups, en llocs on hi hagi herba i sòls rics en matèria orgànica, especialment si han estat abonats amb femtes d'ovella o cabra.

Els compostos psicoactius de Psilocybe són la psilocibina y psilocina. Es tracta de derivats de la triptamina substituïts en posició 4 amb propietats al·lucinògenes semblants a las del LSD. Són alcaloides de la família de les indolalquilamines.

El principi actiu psilocibina o O_fosforil_4_hidroxi_N_dimetil_triptamina, ingerida per l'home es transforma per hidròlisis de la resta fosfóric en psilocina (4_hidroxi_N,N_dimetiltritamina), principi fisiològicament actiu.

S'han aïllat dos compostos més, anàlegs de la psilocibina, anomenats: baeocistina y normaeocistina.

Tots els bolets contenen els alcaloides. El percentatge de cadascun és variable depenent fonamentalment de l'espècie que es tracti i de les condicions particulars en què es desenvolupi.

Emprats amb finalitats mítiques, religioses i màgiques, rituals d'iniciació i fins curatius per chamans, patges i sacerdots des de temps immemorables.

Poden fumar-se, però l'efecte es redueix molt.

20-40 exemplars efecte lleuger 50-100 exemplars efecte intens

No són tòxics però el seu ús reiterat produeix tolerància.

La psilocibina i psilacina són variants de la triptamina, un alcaloide molt similar al neurotransmisor serotonina. Aquesta és la responsable de la percepció sensorial, la regulació de temperatura i l'inici del repòs nocturn. La psilocibina competeix en eficàcia amb la serotonina en la seva unió amb les localitzacions sinàptiques.

Els efectes fisiológics acostumen a ser comuns, mentre que els efectes psíquics varien molt d'una persona a una altra.

La psilocibina és una substància molt poc tòxica que el cos assimila sense dificultat i té un alt marge de seguretat. Fins a 70 vegades la dosis activa mínima (2mg).

Dosis superiors a 5 mg indueixen efectes enteogènics. Mitja hora després de la seva ingestió, una vegada la psilocibina es desfosforila a psilocina, poden desencadenar-se il·lusions visuals, disforia, euforia i una sensació vertiginosa. Una masticació prolongada pot disminuir aquest interval de temps. Altres símptomes sistèmics inclouen rubefacció cutània i facial, taquicàrdia, augment de la temperatura corporal i hipertensió arterial. La duració dels efectes psicodèlics és de tres a sis hores. A dosis elevades pot observar-se un efecte pseudoatropínic, que produeix sequedat a la boca, retenció vesical i un augment en la intensitat de les al·lucinacions.

El tractament de la intoxicació és simptomàtic s'empren les benzodiacepines per tractar els efectes anticolinérgics.

No es coneix dosis letal per l'ésser humà, ni s'han descrit fenòmens de dependència física o psíquica o enverinament.

La bruixa aguda (Psilocybe semilanceata) pertany a un gènere de bolets menuts que creixen pertot arreu. Aquest gènere és molt ben conegut per les seues propietats al·lucinògenes, conegut també com a "bolets màgics", encara que la majoria d'espècies del gènere no contenen alcaloides al·lucinògens. La psilocina i la psilocibina són els composts al·lucinògens responables dels efectes psicoactius de moltes espècies del gènere.

Psilocybe semilanceata: bongui, mongui, sorgin zorrotz.

El gènere pot tenir altres noms com: bolets màgics, bolets sagrats, liberty caps (EUA: barrets de la llibertat), teonanacatl (Mèxic: carn de deu), nti-si-tho (mazatecs: que germina), bolets dels somnis, bolets al·lucinògens.

Madarchen sy'n cynnwys y cyfansoddyn seicowiethredol psilocybin, yw psilocybe semilanceata, a adwaenir hefyd fel y fadarchen hud. O blith holl rywogaethau y madarch psilocybin, hon yw un o'r rhai mwyaf cyffredin ac ynddi hithau y mae'r gyfran uchaf o psilocybin, ac felly mae'n un o'r cryfaf. Mae ganddi gap pigfain adnabyddus, nid anhebyg i siâp cloch hyd at 2.5mm ar ei thraws gydag allwthiad megis tethen ar ei phen. Gall lliw y cap amrywio rhwng melyn a brown gyda rhychau rheiddiol. Mae ei choes fel arfer yn hirfain a'r un lliw â'r cap, neu ychydig yn oleuach. Mae ei sborau'n lliw hufen pan fo'r fadarchen yn ifanc, ond wrth iddi aeddfedu, trônt yn fwy porffor: mesurant rhwng 6.5 a 8.5 micrometr.[2]

Tyf y fadarchen hon mewn dolydd a phorfeydd gwelltog, yn enwedig os ydynt yn llaith ac yn wynebu tua'r gogledd ac wedi eu gwrteithio gan ymgarthion defaid a gwartheg. Ond yn anhebyg i ambell i rywogaeth psilocybin arall, nid yw'r psilocybe semilanceata yn tyfu'n uniongyrchol ar yr ymgarthion; yn hytrach, mae'n rhywogaeth saprobig sydd yn ymborthi ar wreiddiau glaswellt sydd yn pydru.

Cymer y fadarchen hon ei henw cyffredin o'r cap Phrygiaidd, a elwir hefyd yn gap rhyddid (Saesneg: liberty cap), sydd yn ymdebygu i rith y fadarchen.[3] Daw ei henw generig o'r Roeg Hynafol psilos (ψιλός: "esmwyth", "moel") a'r Roeg Bysantaidd κύβη ("pen"); daw ei henw botanegol o'r Lladin semi ("hanner") a lanceata, o'r gair lanceolatus, sy'n golygu "siâp gwaywffon".[4]

Mae psilocybe semilanceata yn ffwng saprobig, sydd yn golygu ei fod yn cael ei faetholion o ddadelfeniad mater organig. Tyf y madarch un ai ar eu pen eu hunain neu mewn grwpiau, gan amlaf mewn dolydd a phorfeydd. Fe'u ceir yn aml mewn caeau sydd wedi cael eu gwrteithio â biswail defaid neu wartheg, er nad ydynt yn tyfu'n uniongyrchol ar y biswail ei hun. Fel ambell i rywogaeth ffwng y glaswelltiroedd, gall Psilocybe tampanensis, Psilocybe mexicana a Conocybe cyanopus ffurfio sglerotia, sef ffurf o'r ffwng sy'n "cysgu", a thrwy hyn yn ei warchod i ryw raddau rhag tanau gwyllt a thrychinebau naturiol eraill.[5]

Ceir y cofnod dilys cyntaf o effeithiau seicoweithredol psilocybe semilanceata ar bobl yn 1799: sonia am deulu Prydeinig a fwytaodd saig a baratowyd gan ddefnyddio madarch a gasglwyd yn Green Park, Llundain. Yn ôl y fferyllydd Augustus Everard Brande, gwelwyd y symptomau a gysylltir yn aml â bwyta madarch hud, gan gynnwys ymledu canhwyllau llygaid a chwerthin digymell.

Yn y 60au cynnar bu'r gwyddonydd Swisaidd Albert Hofman— sy'n adnabyddus am iddo ddarganfod a syntheseiddio'r cyffur seicedelig LSD— yn dadansoddi madarch P. semilanceata a gasglwyd yn Ffrainc a'r Swistir gan y botegydd Roger Heim. Trwy ddefnyddio cromatograffeg bapur, cadarnhaodd Hoffman bresenoldeb psilocybin o 0.25%.

Mae nifer o astudiaethau wedi cael eu cynnal at feintioli cyfran y cyfansoddion rhithweledigaethol a geir yng nghorff y fadarchen P. senilanceata. Nododd Gatz yn 1993 gyfartaledd o 1% psilocybin (a fynegwyd fel canran o gyrff sych y madarch), yn amrywio o isafbwynt o 0.2% i uchafbwynt 2.37%, sef y crynodiad uchaf a gofnodwyd o unrhyw rywogaeth. Tueddir i weld crynodiadau uwch mewn sbesimenau llai o faint, tra bo'r cyfranau absoliwt uchaf i'w gweld yn y madarch mwyaf.

Mae sawl adroddiad o effeithiau bwyta P. semilanceata wedi eu cyhoeddi. Yn nodwedd amlycaf ohonynt yw gwyriadau gweledol, gwriadau yn y modd y canfyddir lliw, dyfnder a ffurf, hyd at rhithweledigaethau gweledol eraill. Mae'r effaith yn debyg i'r rhai a geir o gymeryd LSD, ond yn llai pwerus.

Mae statws cyfreithiol madarch psilocybin yn amrywio ledled y byd. Yn y DU maent yn gyffyr dosbarth A ac fe'i cynhwysir mewn dosbarth o radd gyfatebol yn yr UDA. Yr olaf o wledydd yr Undeb Ewropeaidd i ganiatau ei ddefnyddio oedd yr Iseldiroedd yn Hydref 2008 pan ddaeth deddfwriaeth newydd i rym.[6]

Madarchen sy'n cynnwys y cyfansoddyn seicowiethredol psilocybin, yw psilocybe semilanceata, a adwaenir hefyd fel y fadarchen hud. O blith holl rywogaethau y madarch psilocybin, hon yw un o'r rhai mwyaf cyffredin ac ynddi hithau y mae'r gyfran uchaf o psilocybin, ac felly mae'n un o'r cryfaf. Mae ganddi gap pigfain adnabyddus, nid anhebyg i siâp cloch hyd at 2.5mm ar ei thraws gydag allwthiad megis tethen ar ei phen. Gall lliw y cap amrywio rhwng melyn a brown gyda rhychau rheiddiol. Mae ei choes fel arfer yn hirfain a'r un lliw â'r cap, neu ychydig yn oleuach. Mae ei sborau'n lliw hufen pan fo'r fadarchen yn ifanc, ond wrth iddi aeddfedu, trônt yn fwy porffor: mesurant rhwng 6.5 a 8.5 micrometr.

Tyf y fadarchen hon mewn dolydd a phorfeydd gwelltog, yn enwedig os ydynt yn llaith ac yn wynebu tua'r gogledd ac wedi eu gwrteithio gan ymgarthion defaid a gwartheg. Ond yn anhebyg i ambell i rywogaeth psilocybin arall, nid yw'r psilocybe semilanceata yn tyfu'n uniongyrchol ar yr ymgarthion; yn hytrach, mae'n rhywogaeth saprobig sydd yn ymborthi ar wreiddiau glaswellt sydd yn pydru.

Lysohlávka kopinatá (Psilocybe semilanceata) je psychedelická houba z rodu lysohlávek. Obsahuje psychoaktivní látky psilocybin a baeocystin.

Klobouk je 5–25 mm široký, kónického tvaru, zbarvení je hygrofánní (tj. za vlhka tmavnoucí a při vysychání blednoucí[1]), za vlhka je obvykle kaštanově hnědý, při schnutí rychle bledne do světle tříslově hnědé nebo žluté, někdy získávající olivový nádech.[2] Lysohlávka kopinatá roste od srpna do listopadu mimo les v trávě na pastvinách, lukách, zahradách nebo i na travnatých cestách.[3]

Lysohlávka kopinatá (Psilocybe semilanceata) je psychedelická houba z rodu lysohlávek. Obsahuje psychoaktivní látky psilocybin a baeocystin.

Klobouk je 5–25 mm široký, kónického tvaru, zbarvení je hygrofánní (tj. za vlhka tmavnoucí a při vysychání blednoucí), za vlhka je obvykle kaštanově hnědý, při schnutí rychle bledne do světle tříslově hnědé nebo žluté, někdy získávající olivový nádech. Lysohlávka kopinatá roste od srpna do listopadu mimo les v trávě na pastvinách, lukách, zahradách nebo i na travnatých cestách.

Spids Nøgenhat, Psilocybe semilanceata (på engelsk Liberty Cap) er den næst-stærkeste hallucinogene svamp i Europa.[kilde mangler] Spises den, opnås kraftige hallucinationer. Disse ophører nogle timer efter, alt efter dosering. Grunden til dette er svampens indhold af omkring 2.5 ‰ af stoffet psilocybin.

Hatten er 1-2 cm i diameter, spids kegle- eller klokkeformet, har en lille papil og purpurbrune lameller. Stokken hvidlig og skør.

Spids nøgenhat vokser på fugtige marker og græsplæner, i særdeleshed på de kreaturgræssede.

Friskplukkede spids nøgenhat

Spids Nøgenhat, Psilocybe semilanceata (på engelsk Liberty Cap) er den næst-stærkeste hallucinogene svamp i Europa.[kilde mangler] Spises den, opnås kraftige hallucinationer. Disse ophører nogle timer efter, alt efter dosering. Grunden til dette er svampens indhold af omkring 2.5 ‰ af stoffet psilocybin.

Hatten er 1-2 cm i diameter, spids kegle- eller klokkeformet, har en lille papil og purpurbrune lameller. Stokken hvidlig og skør.

Spids nøgenhat vokser på fugtige marker og græsplæner, i særdeleshed på de kreaturgræssede.

Der Spitzkegelige Kahlkopf (Psilocybe semilanceata) ist der verbreitetste und am häufigsten vorkommende psilocybinhaltige Blätterpilz in gemäßigten Zonen der Erde.

Nach Färbung und Größe ist er ein unauffälliger Lamellenpilz mit fingernagelgroßem Hut und dünnem, nicht ganz geradem Stiel. Er wächst auf eher mageren Grasländern, oft auf herbstlichen Schaf- oder Rinderweiden, aber nie direkt aus dem Tierdung heraus. Sein Myzel lebt als Grasbewohner. Die dunklen Lamellen seiner Fruchtkörper verlaufen nahezu parallel zur Außenseite des Hutes auf dessen Spitze zu – ganz im Gegensatz zu dem häufig mit ihm verwechselten Kegeligen Düngerling (Panaeolus acuminatus) oder dem ebenfalls an ähnlichen, aber dungreicheren Lokalitäten oft zahlreich zu findenden Halbkugeligen Träuschling (Stropharia semiglobata), die alle ebenfalls Dunkelsporer sind.

Das für den Pilz namensgebende Merkmal, der spitzkegelige, kahle Hut, hat einen Durchmesser von 0,5 bis 1,5 Zentimetern und trägt auf der Spitze meist eine kleine, bei feuchter Witterung anfangs fast glasige Ausbeulung, ein „Nippelchen“. Bei Nässe ist seine Färbung dunkelbraun, seine Oberhaut dann klebrig und leicht abziehbar. Bei trockenem Wetter ist der Hut hell ockerfarben. Der Hut bildet meist einen Winkel von 55 Grad, breitet sich aber mit zunehmendem Alter ein wenig aus. Der Hutrand ist meist reifrockartig zusammengezogen und dunkler. Die Lamellen sind zunächst lehmbraun und verfärben sich mit zunehmendem Alter des Pilzes nach dunkelbraun bis purpurn; bei Kälte im Spätherbst bleiben sie allerdings hell, weil dann die Ausbildung der dunklen Sporen unterbleibt. Die Lamellenschneiden sind hell.

Der Stiel besitzt einen Durchmesser von ein bis zwei Millimeter und ist auf kurzrasigem Grasland vier, in höherem bis 13 Zentimeter lang. Er ist weißlich bis ockerfarben, elastisch, also nicht ganz leicht zu zerbrechen. Häufig ist die Stielbasis bläulich verfärbt. Das Bläuen tritt auch durch Druck auf den unteren Teil des Stiels innerhalb rund einer Stunde auf. Das „Hutfleisch“ (die Trama) ist dünn und kann ohne Mühe zerrissen werden. Die Sporen sind elliptisch, dickwandig und glatt und haben eine Größe von etwa 12 – 16 µm × 6 – 8 µm. Der Sporenstaub ist dunkelbraun bis purpurbraun. Der Geschmack ist nicht scharf, sondern wie der kaum wahrnehmbare Geruch rettich- bis grasartig.[1]

Der Spitzkegelige Kahlkopf gilt außerhalb der Tropen als der am häufigsten vorkommende Pilz der Gattung Psilocybe und wächst auf Grasland, meist auf den bodennahen Teilen der Gräser, oft auf Schaf- oder Rinderweiden, aber nie direkt aus deren Tierdung heraus, sowie an grasigen, nicht nährstoffreichen Stellen des Offenlandes („Magerrasen“). Dagegen scheint er Wald- und Kalkgebiete zu meiden. Auch auf natürlich gedüngten Wiesen in Parks und auf Sport- und Golfplätzen ist der Pilz anzutreffen, in Mitteleuropa bei milder Witterung noch bis Ende November.

Er ist im Flachland Nordeuropas genauso anzutreffen wie auf Wiesen in den Mittelgebirgen oder den Almen der Alpenländer. In Tirol wurde er auch in größeren Mengen in Höhen von 1.400 bis 1.700 Metern gefunden, im Schwarzwald bei 820 bis 1.300 Meter über Meereshöhe. Obwohl in tiefer gelegenen Gebieten die Fundhäufigkeit abnimmt, ist hierfür wahrscheinlich nicht der Höhenunterschied, sondern der Einsatz von Gülle oder künstlicher Düngung und Entwässerung in tieferen Lagen die Ursache. Andererseits soll er, laut Krieglsteiner, etwas „salzliebend“ sein. Daher vielleicht seine auffallende Häufigkeit beispielsweise entlang der irischen Westküste. Jedoch steht diesbezüglich ein wissenschaftlicher Nachweis noch aus. Ursprünglich war der Spitzkegelige Kahlkopf wohl nur im gemäßigten Klima Europas und Nordamerikas heimisch, wird aber inzwischen weltweit in gemäßigten bis subtropischen Klimazonen gefunden. In den USA ist er am häufigsten in den Staaten des Nordwestens zu finden. In Europa weisen die Schweizer und Österreichischen Alpen die höchstgelegenen Vorkommen auf. Auch in Wales, Schottland und Norwegen wurden Fundstellen gemeldet.

Die beste Zeit, diesen Pilz anzutreffen, ist im Spätsommer bis Frühherbst, also im August bis Oktober; in milden Lagen ist er aber auch bis Januar vereinzelt zu finden.

Biochemische Untersuchungen ergaben durchschnittliche Gehalte an Psilocybin von 0,8 bis 1,0 Prozent in der Trockenmasse. Daher zählt dieser Pilz zu den potentesten halluzinogenen Arten. Es konnten bei Exemplaren aus wilder Sammlung Psilocybingehalte bis 1,34 Prozent festgestellt werden, bei manchen Exemplaren aus der Schweiz wurden 2,02 Prozent nachgewiesen. Bei geringer Dosis treten Rauschzustände, bei mittlerer Dosis oft farbenfrohe Halluzinationen in wohlabgegrenzten, eventuell „indianischen Mustern“ auf, insbesondere bei geschlossenen Augen.[2] Wegen der Gefahr der ungewollten Aufnahme von Parasitenwurm-Eiern bei auf Viehweiden frisch gesammelten Pilzen sollten diese vor dem Konsum kurz – event. mit Brühwürfel – überbrüht werden oder getrocknet längere Zeit kühl verwahrt worden sein und beispielsweise zusammen mit Vollnuss-Schokolade gründlich gekaut werden. Bei hoher Dosis stellen sich eine verzerrte Wahrnehmung von Zeit und Raum, Gleichgewichts- und Orientierungsstörungen ein. Auch können Atemfrequenz und Atmungstiefe beeinträchtigt sein.

Neben Psilocybin ist eventuell auch das ebenfalls psychoaktiv wirksame Baeocystin nachzuweisen.[3]

Spätneolithische pilzähnliche Felsgravuren im norditalienischen Valcamonica werden vereinzelt, jedoch umstritten, als Beleg für einen entheogenen Gebrauch der Pilze interpretiert.

Der Schweizer Chemiker Albert Hofmann entdeckte bei der Untersuchung von zahlreichen mexikanischen Arten der Gattung Psilocybe den Wirkstoff Psilocybin. Diesem Wissenschaftler gelang auch die Strukturaufklärung und die Vollsynthese dieses halluzinogenen Naturstoffs. Obwohl er seine Entdeckung lediglich in einer kleinen wissenschaftlichen Zeitschrift veröffentlichte, verbreitete sich das Wissen um den einheimischen wirkstoffhaltigen Pilz sehr schnell.

In der Schweiz, in Österreich und Deutschland zählt das Sammeln und Essen seit mindestens 30 Jahren zu einer festen Tradition insbesondere bei jüngeren Leuten (siehe: Venturini und Vannini, Halluzinogene). Eine rituelle Einnahme wurde 1981 erstmals von Linder[4] „im Rahmen eines seit etwa sieben Jahren bestehenden Kults mit komplizierten Schwitzbadritualen, Gebeten, Pfeifenzeremonien (ohne psychoaktive Substanzen), Fastengeboten, Räucherungen, Opferhandlungen und Musik“ beschrieben.

Gegenwärtig ist der Anbau, Verkauf oder Besitz psilocybinhaltiger Pilze in den meisten Ländern der Welt verboten. Auch das Sammeln in der Natur ist in Deutschland ein Verstoß gegen das Betäubungsmittelgesetz. Ein Einsammeln von möglichst vielen Fruchtkörpern durch Erwachsene aus wissenschaftlichem Interesse, beispielsweise zur Ermittlung der Variabilität der Größe der Fruchtkörper und der Sporen, erscheint sinnvoll und dürfte zumindest in Mitteleuropa nirgends beanstandet werden. Freilich sollte vor Betreten herbstlicher Wirtschaftswiesen nach Möglichkeit das Einverständnis der betreffenden Landwirte eingeholt werden.

Psilo, Psilocybinpilz, Zauberpilz, Magic Mushroom, Blue leg, Liberty cap, Kleines Zwergenmützchen, Narrenschwamm, Lanzenförmiger Düngerling, Pixie cap, Sandy sagerose, Witch cap, „narrische/damische/hasch Schwammerl“ (österr./bair. ugs.), Shroom, Spitzköpfe.

Der Spitzkegelige Kahlkopf (Psilocybe semilanceata) ist der verbreitetste und am häufigsten vorkommende psilocybinhaltige Blätterpilz in gemäßigten Zonen der Erde.

Li silocibe des flates, c' est on silocibe (ene sôre di ptit tchampion), ki vént voltî åtoû des flates di vatche, a l' erire-såjhon, el Walonreye et ôte pårt e l' Urope coûtchantrece.

Il a ene copowe pitite ronde grijhe tiesse, avou come come on ptit boursea al miercopete. I vént pa plake di trinte a céncwante åbussons.

Divins, gn a ene drouke ås forvuzions, li silocibene, del famile do LSD. C’ est Albert Hofmann, l’ askepieu des laboratweres Hofmann-Laroche, ki mostra çoula l’ prumî e 1962.

No e sincieus latén : Psilocybe semilanceata.

El Walonreye, on l' trouve tot å long do waeyén-tins dins les waides k' on n' î mete pupont d' biesses. I vént dins les hoûssets, avou totès sôres di yebes rafiantes d' azote, a costé des flates di vatches, des strons di tchvå, des peteles di bedots. Mins i n' crexhe nén so les waides k' on-z î a semé ås ecråxhes tchimikes å bontins udonbén di l' esté.

I fåt co k' il î fwaiye crou et k' il î lujhe li solea assez.

I crexhe pus voltî so les surès teres.

Les efets sont bråmint pus foirts avou des souwés tchampions k' avou des frisses. Les forvuzions arivèt åjheymint avou 10 setchis tchapeas, mins i ndè fåreut ene cwarantinne di frisses po-z aveur li minme efet.

L' efet dispind di l' estat del djin divant d' endè prinde. S' elle est tote seule dins on bwès, ele voerè purade des belès fleurs et des åbes ki s' kitoirdèt. Si li magneu d' droctant tchampion est avou des djins ki l' riwaitnut d' cresse, i va aveur l' epinse k' i gn a des moudreus (u des djindåres) kel shuvnut. Et cori evoye, u s' coûtchî al tere po s' rinde.

Les efets cminçnut après ene grosse dimeye eure, et durer 5 a 8 eures.

Li silocibe des flates, c' est on silocibe (ene sôre di ptit tchampion), ki vént voltî åtoû des flates di vatche, a l' erire-såjhon, el Walonreye et ôte pårt e l' Urope coûtchantrece.

Il a ene copowe pitite ronde grijhe tiesse, avou come come on ptit boursea al miercopete. I vént pa plake di trinte a céncwante åbussons.

Divins, gn a ene drouke ås forvuzions, li silocibene, del famile do LSD. C’ est Albert Hofmann, l’ askepieu des laboratweres Hofmann-Laroche, ki mostra çoula l’ prumî e 1962.

No e sincieus latén : Psilocybe semilanceata.

साइलोस्यबीन मशरूम को सीइकहीदीलीक मशरूम कहा जाता है, यह मशरूम में मुख्या तात्व है जो सीइकहीदीलीक दवाओं साइलोस्यबीन और सेलोबिन बनाने के काम आता है। आम भाषा में जादू मशरूम शरूओम्स है। लगभग 40 प्रजातियों के जीनस सेलोसेइब में पाए जाते हैं। सीलोसिभा कुबीन्सिस ही आम साइलोस्यबीन मशरूम उपोष्णकटिबंधीय क्षेत्रों में पाए जाता है। साइलोस्यबीन मशरूम की संभावना प्रागैतिहासिक काल से इस्तेमाल किया गया है और रॉक कला में दर्शाया गया हो सकता है। कई संस्कृतियों का धार्मिक संस्कार में इन मशरूम का इस्तेमाल किया है। आधुनिक पश्चिमी समाज में, वे अपने साइकेडेलिक प्रभाव के लिए मनोरंजन किया जाता है।

पुरातात्विक साक्ष्य प्राचीन काल में साइलोस्यबीन युक्त मशरूम का प्रयोग इंगित करता है। मध्य पाषाण काल के शैल चित्रों से तास्सीलि एन अज्जीर (Tassili n'Ajjer)(एक प्रागैतिहासिक उत्तर अफ्रीकी साइट पहचान किया है केस्स्पीएन संस्कृति) लेखक जियोर्जियो समोरिनि द्वारा पहचान की गई है। "पत्थरों से युक्त बंदर थ्योरी" कम प्राइमेट से आधुनिक मनुष्य तक विकसित होना के लिये आहार और सांस्कारिक के दूरदर्शी पौधों और स्वाभाविक रूप से होने वाली साइकेडेलिक यौगिकों का उपयोग होत है। साइलोस्यबीन (Psilocybe) जीनस की हालुसेजेनीक (hallucinogenic) प्रजातियों का एक इतिहास है जिस्के तहत मेसोअमेरिका की मूल के लोगों के बीच उपयोग किया है धार्मिक भोज, अटकल और उपचार के लिए, कलमबुस काल से वर्तमान दिन तक। मशरूम पत्थर और रूपांकनों ग्वाटेमाला में Mayan मंदिर खंडहर में पाया गया है। एक प्रतिमा (statuette) जो 200 ई में पाइ गाई है वह साइलोस्यबी (Psilocybe) मेक्सिकाना मशरूम को चित्रण कर रही है जो एक पश्चिम मैक्सिकन शाफ्ट और चैम्बर कब्र के कोलीमा राज्य में पाया गया था। हाल्लुइनोजेनीक (Hallucinogenic) साइलोस्यबी मशरूम को " आज़ितेक्स (Aztecs) के नाम से जाने जाते थे। स्पेनिश माना की मशरूम ने अनुमति दी आज़ितेक्स और आन्या लोग के साथ् संवाद कार्ने दीया वह "शैतान" था। जो स्पेनिश लोग खाना से उन्है रोमन कैथोलिक ईसाई परिवर्तित कर्ती है। स्पेनिश इयुकेरिस्ट के कैथोलिक संस्कार करने के लिये तेओनानसत्ल (teonanácatl) के उपयोग से नीकले दिया गाये। इस इतिहास के बावजूद, कुछ दूरदराज के क्षेत्रों में तेओनानसत्ल (teonanácatl) का उपयोग कर रह थे। पश्चिमी औषधीय साहित्य में हालुसेजेनीक (hallucinogenic) मशरूम का पहला उल्लेख 1799 में लंदन चिकित्सा और शारीरिक जर्नल में छपी। एक आदमी जब वह अपने परिवार के लिए लंदन के ग्रीन पार्क में नाश्ते के लिए साइलोस्यबी सेमीलान्सीअता (semilanceata) मशरूम को खाते थे। उन्हें इलाज करने वाले चिकित्सक बाद में सबसे कम उम्र के बच्चे को "अत्यंत हँसी के दौरे के साथ पाया था। और न ही अपने पिता या माता के खतरों उसा आए।

1955 में, वेलेंटीना और आर गॉर्डन वस्सान पहली ज्ञात पश्चिमी देशों के लिए सक्रिय रूप से एक स्वदेशी मशरूम समारोह में भाग लिए। वस्सान भी 1957 में जीवन में अपने अनुभवों पर एक लेख प्रकाशित करने, उनकी खोज के प्रचार के लिए बहुत कुछ लिखा गाया। 1956 में रोजर हेइम सैइकोअक्तेव मशरूम की पहचान की जो वस्सान साइलोस्यबी के रूप में मेक्सिको से वापस लाया था। और 1958 में, अल्बर्ट होफम्मेन पहले इन मशरूम में सक्रिय यौगिकों के रूप में साइलोस्यबीन (psilocybin) और सेलोसीन (psilocin) की पहचान की। वर्तमान में, साइलोस्यबीन मशरूम उपयोग, ओक्साका के लिए केंद्रीय मैक्सिको से फैले कुछ समूहों के बीच बताया गया है।

साइलोस्यबीन, बसिदिओमेकोता (Basidiomycota) मशरूम की 200 से अधिक प्रजातियों में अलग सांद्रता में मौजूद है। एक 2000 की समीक्षा में (review) साइलोस्यबीन मशरूम की दुनिया भर में वितरण है। गास्तोन गुज़्मान (Gastón Guzmán) और सहयोगियों निम्नलिखित के बीच इन वितरित पीढ़ी को माना। साइलोस्यबी (Psilocybe) (116 प्रजातियों), ज्य्म्नोपिलीउस (Gymnopilus), पानाइओलौस (Panaeolus), कोपेलान्दिअ (Copelandia), हापफोलोमा (Hypholoma), प्लितीउस् (Pluteus), इनोस्य्बी (Inocybe), कोनोसेबी (Conocybe), पानएओलिना (Panaeolina), जेर्रोनेमा (Gerronema), अग्रोस्य्बि (Agrocybe), गालएरिना (Galerina) और म्य्सिना (Mycena)। गुज़्मान एक 2005 की समीक्षा में 144 प्रजातियों के लिए साइलोस्यबीन (psilocybin) युक्त साइलोस्यबी (Psilocybe) वृद्धि की। इनमें से अधिकांश मेक्सिको में पाए जाते हैं (53 प्रजातियों) शेष वितरित रूप से अमेरिका, कनाडा, यूरोप, एशिया, अफ्रीका, ऑस्ट्रेलिया और जुड़े द्वीपों में पाए जाता है। सामान्य में, psilocybin युक्त प्रजातियों आमतौर पर धरण और संयंत्र के मलबे, घास के मैदान आदि में पाया जाता है।

साइलोस्यबीन मशरूम का प्रभाव साइलोस्यबी और साइलोसिन (psilocin) से आते हैं। जब साइलोस्यबीन खाया जाता है। जो साइलोसिन टूट कर निर्माण करने लाग्ता है। यह साइकेडेलिक प्रभाव के लिए जिम्मेदार है। साइलोस्यबी और साइलोसिन, उपयोगकर्ताओं की अल्पकालिक सहिष्णुता में बढ़ जाती है। इस प्रकार उन्हें गाली देना मुश्किल क्योउन्कि वै एक छोटी अवधि के भीतर माशरूम लिया जाता है। कमजोर परिणामी प्रभाव हैं। साइलोस्यबीन (Psilocybin) मशरूम शारीरिक या मानसिक निर्भरता नहीं कर्ता। जहरीला (कभी कभी घातक) जंगली उठाया मशरूम को साइलोस्यबीन मशरूम गालात से ले लिया जाता है। मैजिक मशरूम ब्रिटेन में कम से कम नुकसान के कुछ कारण के रूप में मूल्यांकन की जब तुलनाने एक अध्ययन मनोरंजक दवाओं (recreational drugs) स्वतंत्र वैज्ञानिक समिति ने जब इन पर विध्या की। अन्य शोधकर्ताओं (psilocybin) "शरीर के अंग प्रणालियों को गैर विषैले है"। उच्च उप्योग भय का कारण होने की संभावना है और खतरनाक व्यवहार का कारान बन साक्ता है।

कुछ लोग विभिन्न मानसिक स्थितियों का बेहतर उपचार के विकास के लिए सिंथेटिक और मशरूम व्युत्पन्न साइलोस्यबीन (psilocybin) के उपयोग कार्ते है। उस के सहित क्रोनिक क्लस्टर सिर दर्द, इंपीरियल कॉलेज लंदन और चिकित्सा जॉन्स हॉपकिंस स्कूल में किया हाल के अध्ययनों से निष्कर्ष निकालना, साइलोस्यबीन (psilocybin) अवसादरोधी के रूप में कार्य करता[2] है और FMRI मस्तिष्क स्कैन ने सुझाव दिया गाया है।

Psilocybe semilanceata, commonly known as the liberty cap, is a species of fungus which produces the psychoactive compounds psilocybin, psilocin and baeocystin. It is both one of the most widely distributed psilocybin mushrooms in nature, and one of the most potent. The mushrooms have a distinctive conical to bell-shaped cap, up to 2.5 cm (1 in) in diameter, with a small nipple-like protrusion on the top. They are yellow to brown, covered with radial grooves when moist, and fade to a lighter color as they mature. Their stipes tend to be slender and long, and the same color or slightly lighter than the cap. The gill attachment to the stipe is adnexed (narrowly attached), and they are initially cream-colored before tinting purple to black as the spores mature. The spores are dark purplish-brown in mass, ellipsoid in shape, and measure 10.5–15 by 6.5–8.5 micrometres.

The mushroom grows in grassland habitats, especially wetter areas. But unlike P. cubensis, the fungus does not grow directly on dung; rather, it is a saprobic species that feeds off decaying grass roots. It is widely distributed in the temperate areas of the Northern Hemisphere, particularly in Europe, and has been reported occasionally in temperate areas of the Southern Hemisphere as well. The earliest reliable history of P. semilanceata intoxication dates back to 1799 in London, and in the 1960s the mushroom was the first European species confirmed to contain psilocybin.

The possession or sale of psilocybin mushrooms is illegal in many countries.

The species was first described by Elias Magnus Fries as Agaricus semilanceatus in his 1838 work Epicrisis Systematis Mycologici.[3] Paul Kummer transferred it to Psilocybe in 1871 when he raised many of Fries's sub-groupings of Agaricus to the level of genus.[4] Panaeolus semilanceatus, named by Jakob Emanuel Lange in both 1936 and 1939 publications, is a synonym.[5][6] According to the taxonomical database MycoBank, several taxa once considered varieties of P. semilanceata are synonymous with the species now known as Psilocybe strictipes:[7] the caerulescens variety described by Pier Andrea Saccardo in 1887 (originally named Agaricus semilanceatus var. coerulescens by Mordecai Cubitt Cooke in 1881),[8] the microspora variety described by Rolf Singer in 1969,[9] and the obtusata variety described by Marcel Bon in 1985.[10]

Several molecular studies published in the 2000s demonstrated that Psilocybe, as it was defined then, was polyphyletic.[11][12][13] The studies supported the idea of dividing the genus into two clades, one consisting of the bluing, hallucinogenic species in the family Hymenogastraceae, and the other the non-bluing, non-hallucinogenic species in the family Strophariaceae. However, the generally accepted lectotype (a specimen later selected when the original author of a taxon name did not designate a type) of the genus as a whole was Psilocybe montana, which is a non-bluing, non-hallucinogenic species. If the non-bluing, non-hallucinogenic species in the study were to be segregated, it would have left the hallucinogenic clade without a valid name. To resolve this dilemma, several mycologists proposed in a 2005 publication to conserve the name Psilocybe, with P. semilanceata as the type. As they explained, conserving the name Psilocybe in this way would prevent nomenclatural changes to a well-known group of fungi, many species of which are "linked to archaeology, anthropology, religion, alternate life styles, forensic science, law enforcement, laws and regulation".[14] Further, the name P. semilanceata had historically been accepted as the lectotype by many authors in the period 1938–68. The proposal to conserve the name Psilocybe, with P. semilanceata as the type was accepted unanimously by the Nomenclature Committee for Fungi in 2009.[15]

The mushroom takes its common name from the Phrygian cap, also known as the "liberty cap", which it resembles;[16] P. semilanceata shares its common name with P. pelliculosa,[17] a species from which it is more or less indistinguishable in appearance.[18] The Latin word for Phrygian cap is pileus, nowadays the technical name for what is commonly known as the "cap" of a fungal fruit body. In the 18th century, Phrygian caps were placed on Liberty poles, which resemble the stipe of the mushroom. The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek psilos (ψιλός) 'smooth, bare' and Byzantine Greek kubê (κύβη) 'head'.[19][20] The specific epithet comes from Latin semi 'half, somewhat' and lanceata, from lanceolatus 'spear-shaped'.[21]

In deposit, the spores are a deep reddish purple-brown color. The use of an optical microscope can reveal further details: the spores are oblong when seen in side view, and oblong to oval in frontal view, with dimensions of 10.5–15 by 6.5–8.5 μm. The basidia (spore bearing cells of the hymenium), are 20–31 by 5–9 μm, four-spored, and have clamps at their bases; there are no basidia found on the sterile gill edge. The cheilocystidia (cystidia on the gill edge) measure 15–30 by 4–7 μm, and are flask-shaped with long thin necks that are 1–3.5 μm wide. P. semilanceata does not have pleurocystidia (cystidia on the gill face). The cap cuticle is up to 90 μm thick, and is made of a tissue layer called an ixocutis—a gelatinized layer of hyphae lying parallel to the cap surface. The hyphae comprising the ixocutis are cylindrical, hyaline, and 1–3.5 μm wide. Immediately under the cap cuticle is the subpellis, made of hyphae that are 4–12 μm wide with yellowish-brown encrusted walls. There are clamp connections present in the hyphae of all tissues.[2]

The anamorphic form of P. semilanceata is an asexual stage in the fungus's life cycle involved in the development of mitotic diaspores (conidia). In culture, grown in a petri dish, the fungus forms a white to pale orange cottony or felt-like mat of mycelia. The conidia formed are straight to curved, measuring 2.0–8.0 by 1.1–2.0 μm, and may contain one to several small intracellular droplets.[25] Although little is known of the anamorphic stage of P. semilanceata beyond the confines of laboratory culture, in general, the morphology of the asexual structures may be used as classical characters in phylogenetic analyses to help understand the evolutionary relationships between related groups of fungi.[26]

Scottish mycologist Roy Watling described sequestrate (truffle-like) or secotioid versions of P. semilanceata he found growing in association with regular fruit bodies. These versions had elongated caps, 20–22 cm (7.9–8.7 in) long and 0.8–1 cm (0.3–0.4 in) wide at the base, with the inward curved margins closely hugging the stipe from the development of membranous flanges. Their gills were narrow, closely crowded together, and anastomosed (fused together in a vein-like network). The color of the gills was sepia with a brownish vinaceous (red wine-colored) cast, and a white margin. The stipes of the fruit bodies were 5–6 cm (2.0–2.4 in) long by 0.1–0.3 cm (0.04–0.12 in) thick, with about 2 cm (0.8 in) of stipe length covered by the extended cap. The thick-walled ellipsoid spores were 12.5–13.5 by 6.5–7 μm. Despite the significant differences in morphology, molecular analysis showed the secotioid version to be the same species as the typical morphotype.[27]

There are several other Psilocybe species that may be confused with P. semilanceata due to similarities in physical appearance. P. strictipes is a slender grassland species that is differentiated macroscopically from P. semilanceata by the lack of a prominent papilla. P. mexicana, commonly known as the "Mexican liberty cap", is also similar in appearance, but is found in manure-rich soil in subtropical grasslands in Mexico. It has somewhat smaller spores than P. semilanceata, typically 8–9.9 by 5.5–7.7 μm.[28] Another lookalike species is P. samuiensis, found in Thailand, where it grows in well-manured clay-like soils or among paddy fields. This mushroom can be distinguished from P. semilanceata by its smaller cap, up to 1.5 cm (0.6 in) in diameter, and its rhomboid-shaped spores.[29] P. pelliculosa is physically similar to such a degree that it may be indistinguishable in the field. It differs from P. semilanceata by virtue of its smaller spores, measuring 9–13 by 5–7 μm.[18]

P. semilanceata has also been confused with the toxic muscarine-containing species Inocybe geophylla,[30] a whitish mushroom with a silky cap, yellowish-brown to pale grayish gills, and a dull yellowish-brown spore print.[31] Other similar species include P. cubensis, P. cyanescens, and Deconica coprophila.[22]

Psilocybe semilanceata fruits solitarily or in groups on rich[23][32] and acidic soil,[33][34] typically in grasslands,[35] such as meadows, pastures,[36] or lawns.[23] It is often found in pastures that have been fertilized with sheep or cow dung,[23] although it does not typically grow directly on the dung.[34]

P. semilanceata, like all others species of the genus Psilocybe, is a saprobic fungus,[37][38] meaning it obtains nutrients by breaking down organic matter. The mushroom is also associated with sedges in moist areas of fields,[23] and it is thought to live on the decaying root remains.[39][40]

Like some other grassland psilocybin mushroom species such as P. mexicana, P. tampanensis and Conocybe cyanopus, P. semilanceata may form sclerotia, a dormant form of the fungus, which affords it some protection from wildfires and other natural disasters.[35]

Laboratory tests have shown P. semilanceata to suppress the growth of the soil-borne water mold Phytophthora cinnamomi, a virulent plant pathogen that causes the disease root rot.[41] When grown in dual culture with other saprobic fungi isolated from the rhizosphere of grasses from its habitat, P. semilanceata significantly suppresses their growth. This antifungal activity, which can be traced at least partly to two phenolic compounds it secretes, helps it compete successfully with other fungal species in the intense competition for nutrients provided by decaying plant matter.[42] Using standard antimicrobial susceptibility tests, Psilocybe semilanceata was shown to strongly inhibit the growth of the human pathogen methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The source of the antimicrobial activity is unknown.[43]

Psilocybe authority Gastón Guzmán, in his 1983 monograph on psilocybin mushrooms, considered Psilocybe semilanceata the world's most widespread psilocybin mushroom species, as it has been reported on 18 countries.[44] In Europe, P. semilanceata has a widespread distribution,[45] and is found in Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, the Channel Islands, Czech republic, Denmark, Estonia, the Faroe Islands, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey,[46] the United Kingdom, Ukraine[47] and Pakistan.[48] It is generally agreed that the species is native to Europe;[49] Watling has demonstrated that there exists little difference between specimens collected from Spain and Scotland, at both the morphological and genetic level.[27]

The mushroom also has a widespread distribution in North America. In Canada it has been collected from British Columbia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Ontario and Quebec.[47] In the United States, it is most common in the Pacific Northwest, west of the Cascade Mountains, where it fruits abundantly in autumn and early winter; fruiting has also been reported to occur infrequently during spring months.[23] Charles Horton Peck reported the mushroom to occur in New York in the early 20th century, and consequently, much literature published since then has reported the species to be present in the eastern United States. Gaston Guzman later examined Peck's herbarium specimen, and in his comprehensive 1983 monograph on Psilocybe, concluded that Peck had misidentified it with the species now known as Panaeolina foenisecii.[49][50] P. semilanceata is much less common in South America,[49] where it has been recorded in Chile.[47] It is also known in Australia (where it may be an introduced species)[27] and New Zealand, where it grows in high-altitude grasslands.[51] In 2000, it was reported from Golaghat, in the Indian state of Assam.[52]

The first reliably documented report of Psilocybe semilanceata intoxication involved a British family in 1799, who prepared a meal with mushrooms they had picked in London's Green Park. According to the chemist Augustus Everard Brande, the father and his four children experienced typical symptoms associated with ingestion, including pupil dilation, spontaneous laughter and delirium.[53] The identification of the species responsible was made possible by James Sowerby's 1803 book Coloured Figures of English Fungi or Mushrooms,[54] which included a description of the fungus, then known as Agaricus glutinosus (originally described by Moses Ashley Curtis in 1780). According to German mycologist Jochen Gartz, the description of the species is "fully compatible with current knowledge about Psilocybe semilanceata."[55]

In the early 1960s, the Swiss scientist Albert Hofmann—known for the synthesis of the psychedelic drug LSD—chemically analyzed P. semilanceata fruit bodies collected in Switzerland and France by the botanist Roger Heim. Using the technique of paper chromatography, Hofmann confirmed the presence of 0.25% (by weight) psilocybin in dried samples. Their 1963 publication was the first report of psilocybin in a European mushroom species; previously, it had been known only in Psilocybe species native to Mexico, Asia and North America.[33] This finding was confirmed in the late 1960s with specimens from Scotland and England,[56][57] Czechoslovakia (1973),[58] Germany (1977),[59] Norway (1978),[39] and Belgium and Finland (1984).[60][61] In 1965, forensic characterization of psilocybin-containing mushrooms seized from college students in British Columbia identified P. semilanceata[62]—the first recorded case of intentional recreational use of the mushroom in Canada.[63] The presence of the psilocybin analog baeocystin was confirmed in 1977.[59] Several studies published since then support the idea that the variability of psilocybin content in P. semilanceata is low, regardless of country of origin.[64][65]

Several studies have quantified the amounts of hallucinogenic compounds found in the fruit bodies of Psilocybe semilanceata. In 1993, Gartz reported an average of 1% psilocybin (expressed as a percentage of the dry weight of the fruit bodies), ranging from a minimum of 0.2% to a maximum of 2.37% making it one of the most potent species (but significantly less potent than panaeolus cyanescens).[66] In an earlier analysis, Tjakko Stijve and Thom Kuyper (1985) found a high concentration in a single specimen (1.7%) in addition to a relatively high concentration of baeocystin (0.36%).[67] Smaller specimens tend to have the highest percent concentrations of psilocybin, but the absolute amount is highest in larger mushrooms.[68] A Finnish study assayed psilocybin concentrations in old herbarium specimens, and concluded that although psilocybin concentration decreased linearly over time, it was relatively stable. They were able to detect the chemical in specimens that were 115 years old.[69] Michael Beug and Jeremy Bigwood, analyzing specimens from the Pacific Northwest region of the United States, reported psilocybin concentrations ranging from 0.62% to 1.28%, averaging 1.0 ±0.2%. They concluded that the species was one of the most potent, as well as the most constant in psilocybin levels.[70] In a 1996 publication, Paul Stamets defined a "potency rating scale" based on the total content of psychoactive compounds (including psilocybin, psilocin, and baeocystin) in 12 species of Psilocybe mushrooms. Although there are certain caveats with this technique—such as the erroneous assumption that these compounds contribute equally to psychoactive properties—it serves as a rough comparison of potency between species. Despite its small size, Psilocybe semilanceata is considered a "moderately active to extremely potent" hallucinogenic mushroom (meaning the combined percentage of psychoactive compounds is typically between 0.25% to greater than 2%),[23] and of the 12 mushrooms they compared, only 3 were more potent: P. azurescens, P. baeocystis, and P. bohemica.[71] however this data has become obsolete over the years as more potent cultivars have been discovered for numerous species, especially panaeolus cyanescens which holds the current world record for most potent mushrooms described in published research. According to Gartz (1995), P. semilanceata is Europe's most popular psychoactive species.[36]

Several reports have been published in the literature documenting the effects of consumption of P. semilanceata. Typical symptoms include visual distortions of color, depth and form, progressing to visual hallucinations. The effects are similar to the experience following consumption of LSD, although milder.[72] Common side effects of mushroom ingestion include pupil dilation, increased heart rate, unpleasant mood, and overresponsive reflexes. As is typical of the symptoms associated with psilocybin mushroom ingestion, "the effect on mood in particular is dependent on the subject's pre-exposure personality traits", and "identical doses of psilocybin may have widely differing effects in different individuals."[73] Although most cases of intoxication resolve without incident, there have been isolated cases with severe consequences, especially after higher dosages or persistent use. In one case reported in Poland in 1998, an 18-year-old man developed Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome, arrhythmia, and suffered myocardial infarction after ingesting P. semilanceata frequently over the period of a month. The cardiac damage and myocardial infarction was suggested to be a result of either coronary vasoconstriction, or because of platelet hyperaggregation and occlusion of small coronary arteries.[74]

One danger of attempting to consume hallucinogenic or other wild mushrooms, especially for novice mushroom hunters, is the possibility of misidentification with toxic species.[75] In one noted case, an otherwise healthy young Austrian man mistook the poisonous Cortinarius rubellus for P. semilanceata. As a result, he suffered end-stage kidney failure, and required a kidney transplant.[76] In another instance, a young man developed cardiac abnormalities similar to those seen in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, characterized by a sudden temporary weakening of the myocardium.[77] A polymerase chain reaction-based test to specifically identity P. semilanceata was reported by Polish scientists in 2007.[78] Poisonous Psathyrella species can easily be misidentified as liberty caps.

The legal status of psilocybin mushrooms varies worldwide. Psilocybin and psilocin are listed as Class A (United Kingdom) or Schedule I (US) drugs under the United Nations 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[79] The possession and use of psilocybin mushrooms, including P. semilanceata, is therefore prohibited by extension. Although many European countries remained open to the use and possession of hallucinogenic mushrooms after the US ban, starting in the 2000s (decade) there has been a tightening of laws and enforcements. In the Netherlands, where the drug was once routinely sold in licensed cannabis coffee shops and smart shops, laws were instituted in October 2008 to prohibit the possession or sale of psychedelic mushrooms—the final European country to do so.[80] They are legal in Jamaica and Brazil and decriminalised in Portugal. In the United States, the city of Denver, Colorado, voted in May 2019 to decriminalize the use and possession of psilocybin mushrooms.[81] In November 2020, voters passed Oregon Ballot Measure 109, making Oregon the first state to both decriminalize psilocybin and also legalize it for therapeutic use.[82] Ann Arbor Michigan, and the county it resides in have decriminalized magic mushrooms, possession, sale and use are now legal within the county. In 2021, the City Councils of Somerville, Northampton, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Seattle, Washington, voted for decriminalization.[83]

The Riksdag added Psilocybe semilanceata to Narcotic Drugs Punishments Act under Swedish schedule I ("substances, plant materials and fungi which normally do not have medical use") as of 1 October 1997, published by Medical Products Agency (MPA) in regulation LVFS 1997:12 listed as Psilocybe semilanceata (toppslätskivling).[84]

Psilocybe semilanceata, commonly known as the liberty cap, is a species of fungus which produces the psychoactive compounds psilocybin, psilocin and baeocystin. It is both one of the most widely distributed psilocybin mushrooms in nature, and one of the most potent. The mushrooms have a distinctive conical to bell-shaped cap, up to 2.5 cm (1 in) in diameter, with a small nipple-like protrusion on the top. They are yellow to brown, covered with radial grooves when moist, and fade to a lighter color as they mature. Their stipes tend to be slender and long, and the same color or slightly lighter than the cap. The gill attachment to the stipe is adnexed (narrowly attached), and they are initially cream-colored before tinting purple to black as the spores mature. The spores are dark purplish-brown in mass, ellipsoid in shape, and measure 10.5–15 by 6.5–8.5 micrometres.

The mushroom grows in grassland habitats, especially wetter areas. But unlike P. cubensis, the fungus does not grow directly on dung; rather, it is a saprobic species that feeds off decaying grass roots. It is widely distributed in the temperate areas of the Northern Hemisphere, particularly in Europe, and has been reported occasionally in temperate areas of the Southern Hemisphere as well. The earliest reliable history of P. semilanceata intoxication dates back to 1799 in London, and in the 1960s the mushroom was the first European species confirmed to contain psilocybin.

The possession or sale of psilocybin mushrooms is illegal in many countries.

Psilocybe semilanceata (conocido comúnmente como mongui u hongo de San Juan) es un hongo del género Psilocybe. Esta clase de hongos es conocida por su uso como sustancia enteógena o psicotrópica.

Psilocybe semilanceata mide entre 2 y 5 cm, tiene un sombrero acampanulado con forma de tetilla, carece de anillo, y su color varía entre el blanquecino cuando es pequeño al marrón cuando es grande. Posee un sabor amargo y, si bien mientras crece es blanco perla, una vez se va secando toma un color amarillento y posteriormente tintes purpúreos, azules o verdosos, indicadores de la oxidación de su principio activo, la psilocina.

Crece principalmente a partir de los 600 m de altitud, preferentemente en zonas húmedas. Su cultivo a nivel casero es muy difícil sin tener equipos ni conocimientos de micología.[1][2] Los usuarios de hongos psilocibios prefieren cultivar especies como Psilocybe cubensis (cucumelos), Psilocybe mexicana y Panaeolus cyanescens, que contienen el mismo principio activo (psilocibina).

Psilocybe semilanceata se considera el hongo más común que contiene psilocibina.[3] En Europa, P. semilanceata tiene una amplia distribución, y se encuentra en Alemania, Austria, Bélgica, Bulgaria, en las Islas del Canal, República Checa, Dinamarca, Estonia, Islas Feroe, Finlandia, Francia, Alemania, Georgia, Hungría, Islandia, Irlanda, Italia, Lituania, Países Bajos, Noruega, Polonia, Rumania, Rusia, Eslovaquia, España, Suecia, Suiza y el Reino Unido.[4] En general se acepta que la especie es nativa de Europa.[5] Watling ha demostrado que existe poca diferencia entre las muestras recogidas de España y Escocia, tanto en las características morfológicas y genéticas.[6]

También tiene una amplia distribución en América del Norte. En Canadá se ha obtenido de Columbia Británica, Nuevo Brunswick, Terranova, Nueva Escocia, Isla del Príncipe Eduardo y Quebec.[4] En los Estados Unidos, es más común en el Noroeste del Pacífico, al oeste de la cordillera de las Cascadas, donde fructifica abundantemente en otoño y principios de invierno. Se ha informado que la fructificación también ocurre con baja frecuencia durante los meses de primavera.[7] P. semilanceata es mucho menos común en América del Sur,[5] donde se ha registrado desde el sur de Brasil, Argentina , Uruguay y Chile.[4] También es conocido en Australia (donde puede ser una especie introducida)[6] y Nueva Zelanda, donde crece en pastos de altura.[8] En 2000, se informó de Golaghat, en la India.

La ingestión de Psilocybe semilanceata, tanto crudos como cocinados, produce efectos en el organismo y la personalidad de una manera antagonista a la serotonina, por lo que se puede ver alterada la percepción del espacio tiempo, los sentimientos, el hambre, el sueño o el confort sensitivo. Además puede provocar cuadros de paranoia o manía persecutoria temporal que pueden durar entre 3 y 6 horas aproximadamente; por eso, se desaconseja su consumo si no es en un ambiente controlado.[9]

Produce una agudización de los sentidos y una estimulación efectiva, provocando extraversión y facilitando la expresión de los sentimientos. Algunos de los efectos pueden ir desde cierta hilaridad, desinhibición o locuacidad. Como la mayoría de las drogas alucinógenas, el efecto dependerá principalmente del estado de ánimo de la persona, del ambiente, de la dosis, etc. También puede variar de persona a persona. Los efectos a nivel físico pasan por sensibilidad a la luz, letargo, euforia, tóxica, a veces náuseas y dolor de cabeza.[10]

La psilocina y la psilocibina tienen una estructura química muy similar al factor cerebral serotonina. Los dos alcaloides del hongo, como la LSD, bloquean los efectos de la serotonina en experimentos farmacológicos en distintos órganos. Otras propiedades farmacológicas de la psilocina y la psilocibina son similares a las del LSD. La diferencia principal consiste en la cantidad activa en experimentos con animales y con seres humanos. La dosis activa promedio de psilocina y psilocibina en humanos comienza con 10 mg; de acuerdo a ello, estas dos sustancias son 100 veces menos activas que la LSD, de la cual 0,1 mg constituye una dosis bastante fuerte. Además, los efectos de los alcaloides de los hongos duran entre 4 y 6 horas solamente, mucho menos que los efectos de la LSD (8 a 12 horas).

Psilocybe semilanceata (conocido comúnmente como mongui u hongo de San Juan) es un hongo del género Psilocybe. Esta clase de hongos es conocida por su uso como sustancia enteógena o psicotrópica.

Terav paljak (Psilocybe semilanceata) on värvikuliste sugukonda paljaku perekonda kuuluv hallutsinogeenne seeneliik.

Seen kasvab Euroopas, Venemaal, Indias, Peruus ja Lõuna-Ameerika loodeosas ning Põhja-Ameerikas Oregonis, Washingtoni osariigis, Alaskal ja Labradoril, eelistades märgi, põhja poole avatud sõnnikuga väetatud niite ja karjamaid, ehkki erinevalt samasse perekonda kuuluvast liigist P. cubensis ta otseselt sõnniku sees ei kasva.

Terav paljak on selgelt koonilise kübaraga, millel on väljaulatuv tipp. Kübar on 5–25 mm lai, kõrgus on laiusest poolteist korda suurem. Värske seenekübara alaserv võib olla sooniline ja sissepoole pööratud, kuivades muutuvad need soonekesed märkamatuiks. Värvus varieerub kollasest kuni tumepruunini. Kuivades, sealhulgas kuiva ilmaga muutuvad seened heledamaks. Seenekübara nahk on sile ja limane ning tuleb kergesti ära, eriti noortel eksemplaridel. Jalg on pikk, 4–10 cm pikk ja 2–3 mm lai, sageli lainelise kujuga, elastne, kübaraga sama värvi või sellest pisut heledam, altpoolt vahel sinakas või soomustega. Eoslehed on kübarast tumedamad. Eosed on 8×13 μm suurused, tumepruunid või lillakasmustad, poorsed ja ellipsikujulised. Seen lõhnab nõrgalt rohu või hallituse järele. Maitse puudub või on nõrk ja ebameeldiv.

Skandinaavias ja Eestis ilmub seene maapealne osa augustis ja seda leidub kuni novembri alguseni. Mujal Euroopas kohtab teda septembrist detsembrini. Ida-Kanadas ilmub kübar tavaliselt pärast esimest öökülma ja USA-s kohtab seda jaanuarini.

Seen sisaldab hallutsinogeenseid aineid: trüptamiinide hulka kuuluvaid psilotsübiini ja psilotsiini. Seetõttu on Eestis terava paljaku omamine ja kasutamine keelatud. Narkootiliste ja psühhotroopsete ainete ning nende lähteainete seadus ütleb: "Psilotsiini või psilotsübiini sisaldavate seente kasvatamine on keelatud." [1]. Terava paljaku omamine ja ost-müük on keelatud Venemaal, Suurbritannias ja paljudes teistes riikides.

Seene tarvitamine tekitab hallutsinatsioone ja psühhootilise seisundi, millega võivad kaasneda eufooria või depressioon kalduvusega enesetapule [2]. Seene toime algab 20–45 minutit pärast sissevõtmist ja kestab 4–7 tundi. Purustatud seenesegu tarvitamisel algab toime kiiremini, 10–15 minutiga. Kõige tugevam mõju saabub 1 tunniga ja kestab 2–3 tundi.

Esimese tunni jooksul, kui kõige tugevam mõju pole veel kätte jõudnud, tunnevad inimesed mõõdukaid kõrvalnähte: ebameeldivat tunnet kõhus, külma, jäsemete värinat, hingeldamist ja nägemishäireid. (Siinkohas ei kasutata sõna "kõrvalnähud" meditsiinilises tähenduses, sest meditsiinilises mõttes on kõik psühhedeelsed elamused kõrvalefekt.) Levinud on müüt, justkui tuleksid kõrvalnähud seentesse kogunenud mürkainetest, kuid niimoodi mõjub ka täiesti puhas psilotsübiin.

Seene teaduslik nimi tuleb kreeka keelest, kus "psilo" tähendab 'kiilas' ja "cybe" tähendab 'pea', ning ladina keelest, kus "semi" tähendab 'pool' ja "lanceata" tähendab 'teivastatud', niisiis teiba otsa aetud pool kiilaspead.

Terav paljak (Psilocybe semilanceata) on värvikuliste sugukonda paljaku perekonda kuuluv hallutsinogeenne seeneliik.

Seen kasvab Euroopas, Venemaal, Indias, Peruus ja Lõuna-Ameerika loodeosas ning Põhja-Ameerikas Oregonis, Washingtoni osariigis, Alaskal ja Labradoril, eelistades märgi, põhja poole avatud sõnnikuga väetatud niite ja karjamaid, ehkki erinevalt samasse perekonda kuuluvast liigist P. cubensis ta otseselt sõnniku sees ei kasva.

Terav paljak on selgelt koonilise kübaraga, millel on väljaulatuv tipp. Kübar on 5–25 mm lai, kõrgus on laiusest poolteist korda suurem. Värske seenekübara alaserv võib olla sooniline ja sissepoole pööratud, kuivades muutuvad need soonekesed märkamatuiks. Värvus varieerub kollasest kuni tumepruunini. Kuivades, sealhulgas kuiva ilmaga muutuvad seened heledamaks. Seenekübara nahk on sile ja limane ning tuleb kergesti ära, eriti noortel eksemplaridel. Jalg on pikk, 4–10 cm pikk ja 2–3 mm lai, sageli lainelise kujuga, elastne, kübaraga sama värvi või sellest pisut heledam, altpoolt vahel sinakas või soomustega. Eoslehed on kübarast tumedamad. Eosed on 8×13 μm suurused, tumepruunid või lillakasmustad, poorsed ja ellipsikujulised. Seen lõhnab nõrgalt rohu või hallituse järele. Maitse puudub või on nõrk ja ebameeldiv.

Skandinaavias ja Eestis ilmub seene maapealne osa augustis ja seda leidub kuni novembri alguseni. Mujal Euroopas kohtab teda septembrist detsembrini. Ida-Kanadas ilmub kübar tavaliselt pärast esimest öökülma ja USA-s kohtab seda jaanuarini.

Seen sisaldab hallutsinogeenseid aineid: trüptamiinide hulka kuuluvaid psilotsübiini ja psilotsiini. Seetõttu on Eestis terava paljaku omamine ja kasutamine keelatud. Narkootiliste ja psühhotroopsete ainete ning nende lähteainete seadus ütleb: "Psilotsiini või psilotsübiini sisaldavate seente kasvatamine on keelatud." . Terava paljaku omamine ja ost-müük on keelatud Venemaal, Suurbritannias ja paljudes teistes riikides.

Seene tarvitamine tekitab hallutsinatsioone ja psühhootilise seisundi, millega võivad kaasneda eufooria või depressioon kalduvusega enesetapule . Seene toime algab 20–45 minutit pärast sissevõtmist ja kestab 4–7 tundi. Purustatud seenesegu tarvitamisel algab toime kiiremini, 10–15 minutiga. Kõige tugevam mõju saabub 1 tunniga ja kestab 2–3 tundi.

Esimese tunni jooksul, kui kõige tugevam mõju pole veel kätte jõudnud, tunnevad inimesed mõõdukaid kõrvalnähte: ebameeldivat tunnet kõhus, külma, jäsemete värinat, hingeldamist ja nägemishäireid. (Siinkohas ei kasutata sõna "kõrvalnähud" meditsiinilises tähenduses, sest meditsiinilises mõttes on kõik psühhedeelsed elamused kõrvalefekt.) Levinud on müüt, justkui tuleksid kõrvalnähud seentesse kogunenud mürkainetest, kuid niimoodi mõjub ka täiesti puhas psilotsübiin.

Seene teaduslik nimi tuleb kreeka keelest, kus "psilo" tähendab 'kiilas' ja "cybe" tähendab 'pea', ning ladina keelest, kus "semi" tähendab 'pool' ja "lanceata" tähendab 'teivastatud', niisiis teiba otsa aetud pool kiilaspead.

Kuivatatud teravad paljakud

Kuivav terav paljak

Oharra: ez fidatu soilik orri honetan ematen diren datuez perretxiko bat identifikatzeko orduan. Inolako zalantzarik izanez gero, kontsultatu aditu batekin.

Sorgin-zorrotza edo mongia[erreferentzia behar] (Psilocybe semilanceata) onddo psikodelikoa da. Psilocybe generoko onddo mota bat da, eta oso ezaguna bere subtantzia psikotropikoagatik. Substantzia hau, amerikar indigenek erabiltzen zuten erlijio erritualak egiteko K.a. 1000.urte inguruan.

Egia esan, ez dago jakiterik zehatz-mehatz nolakoa izan zen Psilocybe semilanceataren aurkikuntza, hala ere, esan daiteke lehenengo biztanleriak, probatu egin zituela perretxiko pozointsuak eta jangarriak deberdindu ahal izateko, beste edozein begetalekin egiten zuten bezala. Bestalde, haitzuloetako pinturan ezin izan da droga honi buruz ezertxo ere aurkitu, oso zaila izan baita interpretaziorik ateratzea.

Ezagutzen den lehenego kontaktua perretxiko haluzinogenoekin, pintura mural baten aurkitu zen Amenembet deiturikoaren hilobian 1450.urte inguruan k.a.

Egipton, Indian edo Indotxinan adibidez, ez da perretxikoak kontsumitu zutenaren ebidentziarik edo haiengan sorturiko iresteresari buruzko daturik aurkitu. Aitzitik, badugu berri Mayengan perretxikoek izan zuten interesa X. mende inguruan.

Bestalde, perretxiko haluzinogenoak, beti egon dira magia eta erritualei lotuta, amerika zentralean. Siberia iparraldean ere, oso garrantzitsua izan da beti perretxikoek sorturiko eginkizuna jatorrizko erlijioen sorreran.

Erromatar eta Greziar garaietan ere nahiko eragin sortu zituzten, kantitate ugari kontsumitu zirelarik, elikagai gisa, adibidez Lactarius deliciosus aleen bidez.

Baina, hala ere, perretxikoek historian zehar oso eragin kaltegarriak sortu dituzte, Klaudio enperadorea bezalako pertsonak hiltzerainokoak, gaur egungo egoerara heldu arte, dosi handiegiak kontsumitzearen ondorioz.

Onddo hauek jaterakoan hainbat modu ezberdinetan eragin diezazuke, batzuk besteak baino atseginagoak izan daitezkeelarik. Dena den, ohikoenak hurrengoak dira:

Luzaroan zenbait ondorio sor ditzakete batez ere astean behien baino gehiagotan hartu ez gero. Ondorio hauek ez dira inondik ere atseginak eta nahiko arazo larriak suerta ditzakete:

Sorgin-zorrotza edo mongia[erreferentzia behar] (Psilocybe semilanceata) onddo psikodelikoa da. Psilocybe generoko onddo mota bat da, eta oso ezaguna bere subtantzia psikotropikoagatik. Substantzia hau, amerikar indigenek erabiltzen zuten erlijio erritualak egiteko K.a. 1000.urte inguruan.

Suippumadonlakki (Psilocybe semilanceata) eli silokki on useimmiten pohjoisen pallonpuoliskon ravinteikkailla mailla tavattu madonlakkeihin kuuluva myrkylliseksi luokiteltu sieni[2]. Sieni ei fyysisesti vahingoita ihmiskehoa[3] vaan myrkytysoireet ovat väliaikaisia ja johtavat muun muassa tajunnantilan moninaisiin muutoksiin. Suippumadonlakkia käytetään keskushermostovaikutustensa vuoksi yleisesti psykedeelisenä päihteenä, kuten muitakin psilosybiinisieniä. Lainsäädäntö määrittelee Psilosybe-sienet huumausaineiksi.[4] Suippumadonlakin tieteellisen nimen lajiosa koostuu latinankielisistä sanoista "semi" (puoli, puoliksi) ja "lanceata" (keihästetty, lävistetty).

Suippumadonlakin lakki on 0,5-1,5 cm leveä ja 1,5-2 cm korkea. Muodoltaan lakki on pipomainen tai kellomainen ja terävänipukallinen. Lakki on kosteusmuuntuva: kosteana lakin yläpinta on vihertävän ruskea ja kuivana vaaleampi, savenvärinen. Kosteana se myös tuntuu tahmealta ja hyytelömäiseltä. Sieni on tiheähelttainen. Sen heltat ovat kapeatyvisiä ja väriltään yläreunasta oliivinruskeita, keskeltä purppuranruskeita ja terästä vaaleita. Kosteana heltat kuultavat lakin läpi. Nuorten sienten lakit ovat alareunasta sisäänpäin kääntyneitä. Suippumadonlakin jalka on 4-10 cm pitkä ja 0,1-0,2 cm paksu, rakenteeltaan sileä ja joustava. Väriltään se on kiiltävän vaalea, mutta tummenee tyveä kohti. Vahingoittuneet varren osat voivat muuttua sinertäviksi.[5][6]

Suippumadonlakin annulus on siro, ruskea, seittimäinen ja nopeasti katoava. Se jättää varteen tahmean ja tumman, itiöpölyn värisen kohdan. Itiöpöly on purppuranruskeaa ja hienorakenteeltaan itiöt ovat soikeita, sileitä ja ituhuokosellisia. Pituudeltaan ne ovat 12-13,5 µm ja leveydeltään 7-8,5 µm.[5][6]

Suippumadonlakin maku on mieto ja haju heikko.[5]

Suippumadonlakki on karikkeen lahottaja, joka kasvaa yksittäin tai ryhmissä lehmien, hevosten ja lampaiden laitumilla ruohikossa ja ruohotuppaissa kosteilla alueilla sekä lannoitetuilla nurmikoilla. Lajia ei kuitenkaan tavata lannalla. Kasvukausi kestää elokuun lopusta lokakuuhun, kunnes lämpötilat ovat laskeneet alle 5 asteen, mutta itiöemiä voi löytää maastosta pakkasten tuloon saakka.

Sieni on levinnyt laajalti pohjoiselle pallonpuoliskolle. Sitä esiintyy mm. Lounais-Yhdysvalloissa, Britteinsaarilla, Länsi-Euroopassa ja Skandinaviassa. Suomessa suippumadonlakki voi esiintyä pihoilla, puistoissa, puutarhoissa, nurmikoilla, laitumilla, tienvierillä, kosteissa metsien painanteissa, runsaasti lannoitetulla maalla, ruohikossa tai karikkeella koko maan alueella.[7]

Suippumadonlakki sisältää useita keskushermostostoon vaikuttavia aineita[8]: psilosiiniä, baeosystiiniä sekä psilosybiiniä, jota itiöemät sisältävät keskimäärin noin 10 mg/g eli 1,5 % sienten kuivapainosta. Tätä suurempia pitoisuuksia ei löydy muista Suomen alueella tunnetusti esiintyvistä psilosybiinisienistä.[7][9]

Suippumadonlakki ei yleensä fyysisesti vaurioita keskushermostoa tai muutoinkaan ihmiskehoa, ja sen vaikutukset tajunnantilaan ovat väliaikaisia. Sieni määritellään hermostovaikutustensa vuoksi kuitenkin myrkylliseksi.[2][3] Mahdollisia myrkytysoireita ovat muun muassa aistiharhat ja hyvänolontunne sekä muut psykedeeliset vaikutukset. Myös negatiivisia vaikutuksia voi ilmetä: ahdistusta ja suuremmilla annoksilla jopa paniikkikohtauksia.

Hallusinaatioiden ja sekavuuden ohella mahdollisia myrkytysoireita ovat huimaus, jäykkyys, pahoinvointi, virtsaamisvaikeus, korkea kuume sekä kouristelu.Lääkehiilestä ei yleensä ole apua, koska sienen myrkyt imeytyvät hyvin nopeasti ja oireet saattavat alkaa jo 10–30 minuutin kuluessa sienen nauttimisesta. Suippumadonlakki on lisäksi mahdollista sekoittaa hengenvaarallisiin myrkkysieniin, kuten valkorisakkaaseen.selvennä Myrkytystä hoidetaan ensisijaisesti rauhoittelemalla ahdistunutta potilasta ja pitämällä hänet hiljaisessa ja rauhallisessa ympäristössä; voimakkaasti oireileva potilas tulee toimittaa lääkäriin.[10][11][12]

Psilosybiinin terapeuttista potentiaalia on tutkittu mm. terminaalisen sairauden aiheuttaman kuolemanpelon hoitokeinona.[13] Tutkimuskontekstissa sen on havaittu olevan mielenterveydelle edullista ja kohentavan mielialaa kroonisesti.[14] Isojen annosten (0,43mg/kg psilosybiiniä) havaittiin aiheuttavan mystisiä ja uskonnollisia kokemuksia. Kahden kuukauden jälkeen tehdyssä kyselytutkimuksessa 55 % koehenkilöistä luokitteli kokemuksen kuuluvan elämänsä viiden merkittävimmän henkisen kokemuksen joukkoon, ja 12 % luokitteli sen kaikista merkittävimmäksi. Sitä verrattiin mm. ensimmäisen lapsen syntymään tai vanhemman kuolemaan.[15] Valvomaton käyttö voi kuitenkin aiheuttaa traumaattisia kokemuksia tai onnettomuuksia.Lainsäädäntö Sienen kerääminen, hallussapito, käyttö, kasvattaminen ja myynti on kielletty Suomen huumausainelainsäädännössä.[7] Korkein oikeus linjasi vuonna 2017, että Psilosybe-sienet eivät ole rikoslain tarkoittamia erittäin vaarallisia huumausaineita.[16]

Lähteet

Suippumadonlakki (Psilocybe semilanceata) eli silokki on useimmiten pohjoisen pallonpuoliskon ravinteikkailla mailla tavattu madonlakkeihin kuuluva myrkylliseksi luokiteltu sieni. Sieni ei fyysisesti vahingoita ihmiskehoa vaan myrkytysoireet ovat väliaikaisia ja johtavat muun muassa tajunnantilan moninaisiin muutoksiin. Suippumadonlakkia käytetään keskushermostovaikutustensa vuoksi yleisesti psykedeelisenä päihteenä, kuten muitakin psilosybiinisieniä. Lainsäädäntö määrittelee Psilosybe-sienet huumausaineiksi. Suippumadonlakin tieteellisen nimen lajiosa koostuu latinankielisistä sanoista "semi" (puoli, puoliksi) ja "lanceata" (keihästetty, lävistetty).

Psilocybe semilanceata, psilocybe lancéolé ou psilocybe fer de lance, est une espèce de champignons qui contient des substances psychoactives qui sont la psilocybine et la baeocystine. Il est qualifié comme un champignon hallucinogène ou champignon psychédélique. Il est à la fois un des champignons à psilocybine les plus présents dans la nature, et un des plus puissants.

Le Psilocybe semilanceata est l'espèce type du genre Psilocybe[1]. Ce petit champignon très répandu dans le monde est constitué d’un chapeau visqueux ne dépassant pas 2,5 cm et surmonté d’un mamelon proéminent. Son chapeau forme un dégradé de jaune à brun, couvert de rainures radiales lorsqu'il est humide, et prend une couleur plus claire au fur et à mesure qu'il vieillit et fane. Le stipe a tendance à être mince et long, ainsi que de la même couleur ou légèrement plus clair que le chapeau. La fixation des lamelles au stipe est adnexée (étroitement attachée). Les lamelles sont d'abord de couleur crème avant de se colorer en pourpre dès que les spores mûrissent. Les spores sont en masse d'un brun violacé sombres, de forme ellipsoïde, et mesurent 10,5-15 par 6,5-8,5 micromètres.

Ce champignon pousse dans les prairies herbeuses, et habitats similaires, particulièrement humides, qui sont fertilisés par du bétail. C'est une espèce saprophyte qui se nourrit des cellules moribondes de racines de différentes espèces d'herbes. À l'inverse du Psilocybe cubensis, cette espèce ne pousse pas dans des déjection d'animaux ni ne s'en nourrit. Il est largement répandu dans les régions à climat tempéré de l’hémisphère Nord, particulièrement en Europe.

Le cas le plus ancien connu d'intoxication au Psilocybe semilanceata a été constaté en 1799 à Londres. Sa consommation volontaire a commencé dans les années 1960 lorsque le champignon a été déclaré la première espèce européenne contenant de la psilocybine.

La possession ou la vente de champignons à psilocybine est illégale dans beaucoup de pays.

En 1838, Elias Magnus Fries décrit l'espèce pour la première fois dans son Epicrisis Systematics Mycologici avec comme nom binominal original Agaricus semilanceatus[2]. En 1871, Paul Kummer transfère l'espèce dans le genre Psilocybe après avoir élevé au rang de genre de nombreux subdivisions d'Agaricus[3]. Le taxon Panaeolus semilanceatus décrit par Jakob Emanuel Lange dans des publications de 1936 et 1939 est considéré comme un synonyme[4],[5]. Selon la base de données taxinomique MycoBank, plusieurs taxons ayant été considérés des variétés de P. semilanceata sont depuis devenus synonymes de Psilocybe strictipes[6] : c'est le cas des variétés caerulescens décrite par Pier Andrea Saccardo en 1887 (originellement nommée Agaricus semilanceatus Var. coerulsecens par Mordecai Cubitt Cooke en 1881), microspora décrite par Rolf Singer en 1969, et obtusata décrite par Marcel Bon en 1985[7],[8],[9].