en

names in breadcrumbs

Ethiopia is one of the most impacted countries from Histoplasma farciminosum spanning the whole country and spreading continuously.[9] This contagious disease is spread through markets where animals interact and then travel to different locations where the spores can relocate for new infestations. It does not compete with any other species of fungi for its host making this disease highly deadly. As recorded in 2006 Ethiopia ranks epizootic lymphangitis second behind only African horse sickness as the most impactful horse diseases in the country.[3] Other countries have been much more successful at eradicating the disease including Great Britain which was able to do so by 1906 through direct slaughter once the disease was identified.[8] Epizootic lymphangitis has slowly been contained to a number of areas and countries, but in much poorer countries where citizens rely on their equine species for survival the end to this disease does not seem to be coming near.

Developing countries have to deal with a lot of stress on a daily basis usually surrounded around basic survival. One problem within the hot moist countries has come from the disease epizootic lymphangitis caused by Histoplasma farciminosum. This equine killer has infested thousands of animals with little to no competition. Although veterinary clinics are attempting to disperse antibiotics to people in their countries they are finding that not all animals will respond to the experimental drugs.[2] The prices are just too high for these drugs and the risk and reward is not worth it to most handlers on very strict budgets. A study done back in 1985 was able to conclude that on average every case of epizootic lymphangitis caused a net loss of $1,683 US dollars.[3] This extraneous amount can hurt families in countries like Ethiopia where equine species are the main form of transportation as well as a form of work.

Histoplasma farciminosum is endemic to many places across the world including Ethiopia, India, the Middle East, Northern Africa, and many other locations.[8] It sustains itself in areas between 1600 to 2400 meters above sea level where rainfall is common and it is warm all year round.[4] These seem to be the most adequate conditions for this fungus to survive and spread readily.

Equine species are very susceptible to becoming hurt or sick from a number of causes and Histoplasma farciminosum is just one more thing added to the list. In developing countries horses and donkeys are used not only for transportation but also for working purposes to make a livelihood. This fungus targets mainly horses, mules, and donkeys but other close relatives including camels and cattle have been previously reported.[2] It feeds off the tissues of the animals internally as well as externally once it enters the system through either open sores, breathing the spores in, or bugs spreading the spores to the hosts.

Although Histoplasma farciminosum is most commonly known and recognized for its parasitic portion of its life it is surprisingly only part of its life story. Histoplasma farciminosum is unique in the fact that it has not only a parastitic portion to its life but also a saprophytic portion during its larger growth form.[8] It receives energy directly through the tissues of its host or retrieves its nutrients from decomposing materials. When invading the tissues of equine species the disease it causes is referred to as Epizootic Lymphangitis, which is highly contagious amongst populations and puts high risk to a large number of animals.[10] Most infected animals in current endemic countries tend to be worked while they are infected furthering the spread of the disease. As H. farciminosum persists the equine species eventually cannot fight the disease and are left to die on a regular basis.[2]

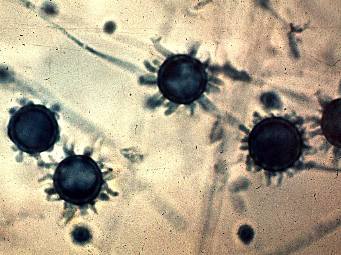

Histoplasma farciminosum is a fairly common causer of disease in equine species within developing countries where large populations of horses and donkeys interact on a regular basis. The dimorphic fungi goes unnoticed until it invades its host where it is much easier to identify.[8] Once H. farciminosum invades its host it produces lesions filled with pus which can be extracted and examined for its spore presence. The spores are said to look like they have a halo around them and very closely resemble yeast.[9] The other phase in its life cycle reveals more of its relationship with other fungi due to its presence of a saprophytic mycelial network in soils.[1] Histoplasma farciminosum also has septate hyphae making up its mycelial network which can be further used as a tool for identification.[4] Due to this dimorphic life cycle H. farciminosum has a large number of opportunities to continue to spread to new hosts. This fungus does not have a distinctive characteristic that stands out amongst other fungi, but it specifically only targets equine species and produces routine side effects.

] The first major studies on Histoplasma were not conducted until the early twentieth century and were confined to research on the human infecting variety Histoplasma capsulatum. In 1903 Doctor Samuel Taylor Darling was sent down to Panama to address new relevant diseases that were appearing within the Panama Canal worker populations.[6] Samples were taken from patients and identified at the microscopic level. Blood smears showed halo shaped figures invading the blood which Darling falsely claimed to be a protozoan variety of parasite.[9] Several years later in 1912 a Brazilian pathologists Henrique da Rocha-Lima correctly identified the parasite to be a variety of fungus.[6] He was able to correctly identify the equine variety where the species was correctly renamed to Histoplasma capsulatum var. farciminosum (Hisstoplasma farciminosum for short). Further phylogenetic research was concluded following da Rocha-Lima’s research to factually identify this species for its official name change in 1985.[6]

[1]Al-Ani, F. K. (1999) Epizootic lymphangitis in horses: a review of the literature. Revue

Scientifique et Technique – Office International des Epizooties 18, 691-699

[2]Ameni, Gobena. 2006. "Epidemiology of equine histoplasmosis (epizootic lymphangitis) in

carthorses in Ethiopia."Veterinary Journal172, no. 1: 160-165.Academic Search

Premier, EBSCOhost(accessed October 22, 2017).

[3]Ameni, Gobena. 2006. "Preliminary trial on the reproducibility of epizootic lymphangitis

through experimental infection of two horses."Veterinary Journal172, no. 3: 553-

555.Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost(accessed October 21, 2017).

[4]Ameni, G, Terefe, W, & Hailu, A 2006, 'Histofarcin test for the diagnosis of epizootic

lymphangitis in Ethiopia: development, optimisation, and validation in the

field',Veterinary Journal, vol. 171, no. 2, pp. 358-362. Available from:

10.1016/j.tvjl.2004.10.017. [21 October 2017].

[5].Gurein,S.Abebe,F.TouatiLymphangite epizootique du cheval en Ethiopie Journal of

Mycological Medicine,2(1992), pp.1-5

[6]Hagan, Teresa. “The Discovery and Naming of Histoplasmosis: Samuel Taylor Darling.”

Antimicrobe, accessed October 23, 2017.

[7]Inglis, R. (1997) Ocular disease of the donkey. In The Professional Handbook of the Donkey.

3rd edn. Ed E. D. Svendsen. London, Whittet Books. pp 37- 42

[8]Jones, Karen. 2006. "Epizootic lymphangitis: The impact on subsistence economies and animal

welfare."Veterinary Journal172, no. 3: 402-404.Academic Search Premier,

EBSCOhost(accessed October 22, 2017).

[9]Powell, R. K., N. J. Bell, T. Abreha, K. Asmamaw, H. Bekelle, T. Dawit, K. Itsay, and G. A.

Feseha. 2006. "Cutaneous histoplasmosis in 13 Ethiopian donkeys."Veterinary Record:

Journal Of The British Veterinary Association158, no. 24: 836-837.Academic Search

Premier, EBSCOhost(accessed October 21, 2017).

[10]R.J.Weeks,A.A.Padhye,L.AjelloHistoplasma capsulatum variety farciminosum: a new

combination forHistoplasma farciminosum Mycologia,77(1985), pp.964-970

Histoplasma farciminosum is a parasitic fungi more commonly known as the precursor for equine species to contract epizootic lymphangitis.[10] This fungus has been tormenting equine species namely horses, donkeys, and goats in undeveloped and developing countries for centuries.[2] The disease was never officially identified at any point in time due to how spread out the disease is as well as the misidentification for generations and common name confusion. Unfortunately the side effects of the fungus resemble a variety of different diseases including malaria in humans.[6]

Macroconidia and microconidia, present in the mould form, are both unicellular, round, and hyaline. Macroconidia are large (8-16 um diameter), thick-walled, and often have prevalent fingerlike spines. Microconidia are smooth or rough-walled, abundant, grow from conidiophores produced at right angles to hyphae, and are smaller in diameter (2-5 um). Hyphae are septate and hyaline.6 Culture color ranges from white in a fresh sample to a more brownish color as it ages.

Microconidia are the primary elicitors of the disease. Upon inhalation, the spores germinate, and the mycelium morphs to the invasive yeast at body temperature. Yeast colonization takes place in the human body because the fungus is able to evade lysosome fusion, but continue replicating in phagosomes. At 37˚C, the yeast form reproduces by budding. Distinguishing Histoplasma capsulatum from Blastomyces dermatitidis, H. capsulatum yeast cells form a narrower base when budding.

See Tom Volk’s Fungi Website: http://tomvolkfungi.net/

Histoplasma capsulatum can be found throughout the world, but is predominant in the United States, specifically found in states of the eastern and Midwest area of the country. Certain regions with a higher concentration of the species include those with higher average temperatures (68-90˚F), and a high humidity (>60%), particularly the region of the Ohio Mississippi Valley.2 It may often be found where starlings congregate.

Histoplasma capsulatum is a true pathogenic, thermal dimorphic fungus, existing in the form of mycelia at 25˚C and in the form of yeast at 37˚C (body temperature). Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum causes the disease most commonly labeled Histoplasmosis mentioned below. Its teleomorph name is Ajellomyces capsulatus,8, although the teleomorph is seldom seen.

Histoplasma capsulatum at http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/jan2000.html

Although it can be isolated from caves, the soil is the major reservoir for Histoplasma capsulatum. Soil with a high nitrogen content and bird or bat guano are especially favorable environments. Birds do not carry the disease, but the manure acts as a nutrient source for fungi already present, while bats are able to be infected with Histoplasma capsulatum.5

From a morphological standpoint, H. capsulatum is similar to a nonpathogenic parasite of mushrooms, Sepedonium and also to a nonpathogenic fungi Renispora flavissima. Sepedonium differs in the fact that the mushroom structure is slightly bigger, contains bright yellow conidia, includes no microconidia, and is not dimorphic. Renispora flavissima is a member of Chrysosporium species and differs from H. capsulatum because it is not dimorphic, includes arthroconidia, and has no macroconidia.2

When Histoplasma capsulatum elicits Histoplasmosis, there are other species that can be similar. Tuberculosis is similar with its flu-like symptoms that both cause in humans upon infection: fever, cough, chills, and general malaise. Otherwise, Cryptococcus neoformans and Chlamydia psittaci are similar because these two species also cause disease by inhalation exposure from infected manure of certain birds.

Histoplasma capsulatum has no positive benefit use to humans, but has a great relevance to the diseases that are able to infect humans. H. capsulatum is the etiological agent of Histoplasmosis and can cause varying degrees of clinical disease. In its least severe form, acute pulmonary histoplasmosis, it is asymptomatic and the great majority (95%) of people in the endemic areas have already been inoculated with this form at some point in their lives.1 The other gradually more severe, but extremely rare forms of the disease include: primary cutaneous histoplasmosis and disseminated histoplasmosis. Overall, the fungal species can infect healthy people, but chronic lung disease patients, the older aged, people who work with soil, and young children are more apt to infection.4 This is also one of the fungal AIDS associated pathogen besides Candida albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans and Blastomyces dermatitidis in the United States.5 Main treatments for the more severe, symptomatic forms of the disease are Amphotercin B, Ketoconazole, or Itraconazole.

Other names to describe the disease it causes, besides Histoplasmosis including: Darling’s disease, reticuloendotheliosis, Ohio Valley disease, Maria fever, and tingo.

Histoplasma capsulatum is a species of dimorphic fungus. Its sexual form is called Ajellomyces capsulatus. It can cause pulmonary and disseminated histoplasmosis.

H. capsulatum is "distributed worldwide, except in Antarctica, but most often associated with river valleys"[1] and occurs chiefly in the "Central and Eastern United States"[2] followed by "Central and South America, and other areas of the world".[2] It is most prevalent in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. It was discovered by Samuel Taylor Darling in 1906.

H. capsulatum is an ascomycetous fungus closely related to Blastomyces dermatitidis. It is potentially sexual, and its sexual state, Ajellomyces capsulatus, can readily be produced in culture, though it has not been directly observed in nature. H. capsulatum groups with B. dermatitidis and the South American pathogen Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in the recently recognized fungal family Ajellomycetaceae.[3][4] It is dimorphic and switches from a mould-like (filamentous) growth form in the natural habitat to a small, budding yeast form in the warm-blooded animal host.

Like B. dermatitidis, H. capsulatum has two mating types, "+" and "–". The great majority of North American isolates belongs to a single genetic type,[5][6] but a study of multiple genes suggests a recombining, sexual population.[6] A recent analysis has suggested that the prevalent North American genetic type and a less common type should be considered separate phylogenetic species, distinct from H. capsulatum isolates obtained in Central and South America and other parts of the world. These entities are temporarily designated NAm1 (the rare type, which includes a famous experimental isolate designated "the Downs strain") and NAm2 (the common type).[6] As yet, no well-established clinical or geographic distinction is seen between these two genetic groups.

In its asexual form, the fungus grows as a colonial microfungus strongly similar in macromorphology to B. dermatitidis. A microscopic examination shows a marked distinction: H. capsulatum produces two types of conidia, globose macroconidia, 8–15 µm, with distinctive tuberculate or finger-like cell wall ornamentation, and ovoid microconidia, 2–4 µm, which appear smooth or finely roughened. Whether either of these conidial types is the principal infectious particle is unclear. They form on individual short stalks and readily become airborne when the colony is disturbed. Ascomata of the sexual state are 80–250 µm, and are very similar in appearance and anatomy to those described above for B. dermatitidis. The ascospores are similarly minute, averaging 1.5 µm.

The budding yeast cells formed in infected tissues are small (about 2–4 µm) and are characteristically seen forming in clusters within phagocytic cells, including histiocytes and other macrophages, as well as monocytes. An African phylogenetic species, H. duboisii, often forms larger yeast cells to 15 µm.

H. capsulatum is "distributed worldwide, except in Antarctica, but most often associated with river valleys"[1] and occurs chiefly in the "Central and Eastern United States"[2] followed by "Central and South America, and other areas of the world"[2] It is most prevalent in the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys.

The enzootic and endemic zones of H. capsulatum can be roughly divided into core areas, where the fungus occurs widely in soil or on vegetation contaminated by bird droppings or equivalent organic inputs, and peripheral areas, where the fungus occurs relatively rarely in association with soil, but is still found abundantly in heavy accumulations of bat or bird guano in enclosed spaces such as caves, buildings, and hollow trees. The principal core area for this species includes the valleys of the Mississippi, Ohio, and Potomac Rivers in the USA, as well as a wide span of adjacent areas extending from Kansas, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio in the north to Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas in the south.[7][8][9] In some areas, such as Kansas City, skin testing with the histoplasmin antigen preparation shows that 80–90% of the resident population have an antibody reaction to H. capsulatum, probably indicating prior subclinical infection.[7] Northern U.S. states such as Minnesota, Michigan, New York and Vermont are peripheral areas for histoplasmosis, but have scattered counties where 5–19% of lifetime residents show exposure to H. capsulatum. One New York county, St. Lawrence county (across the St. Lawrence River from the Cornwall– Preston – Brockville area of Ontario, Canada) shows exposures over 20%.[7]

The distribution of H. capsulatum in Canada is not as well documented as in the US. The St. Lawrence Valley is probably the best known endemic region based both on case reports and on a number of skin test reaction studies that were done between 1945 and 1970. The Montreal area is a particularly well documented endemic focus, not just in the agricultural regions surrounding the city[10] but also within the city itself.[11] The Mount Royal area in central Montreal, especially the north and east sides of Mt. Royal Park, showed exposure rates between 20 and 50% in schoolchildren[11] and locally lifetime-resident university students.[12] A particularly high rate of 79.3% exposure was shown in St. Thomas, Ontario, south of London, Ontario, after 7 local residents had died of histoplasmosis in 1957.[13] Based on numerous small regional studies, histoplasmin skin test reactors form ca. 10–50 % of the population in much of southern Ontario and in Quebec’s St. Lawrence Valley, ca. 5% in southern Manitoba and some northerly parts of Quebec (e.g., Abitibi-Témiscamingue), and ca. 1% in Nova Scotia.[12][13][14][15][16] Exposure of aboriginal Canadians occurs remarkably far north in Quebec,[17][18] but has not been reported in similar boreal biogeoclimatic zones in many other parts of Canada. Recently and remarkably, a cluster of four indigenously acquired cases of histoplasmosis was shown to be associated with a golf course in suburban Edmonton, Alberta.[19] Examination suggested that local soil was the source.

Histoplasmosis is usually a subclinical infection that does not come to the attention of the person involved. The organism tends to remain alive in the scattered pulmonary calcifications; therefore, some cases are detected by emergence of serious infection when a patient becomes immunocompromised, perhaps decades later. Frank cases are most often seen as acute pulmonary histoplasmosis, a disease that resembles acute pneumonia but is usually self-limited.[7][20] It is most often seen in children newly exposed to H. capsulatum or in heavily exposed individuals. Erythematous skin conditions arising from antigen reactions may complicate the disease, as may myalgias, arthralgias, and rarely, arthritic conditions. Emphysema sufferers may contract chronic cavitary pulmonary histoplasmosis as a disease complication; eventually the cavity formed may be occupied by an Aspergillus fungus ball (aspergilloma), potentially leading to massive hemoptysis.[20] Another uncommon form of histoplasmosis is a slowly progressing condition known as granulomatous mediastinitis, in which the lymph nodes in the mediastinal cavity between the lungs become inflamed and ultimately necrotic; the swollen nodes or draining fluid may ultimately affect the bronchi, the superior vena cava, the esophagus or the pericardium. A particularly dangerous condition is mediastinal fibrosis, in which a subset of individuals with granulomatous mediastinitis develop an uncontrolled fibrotic reaction that may press on the lungs or the bronchi, or may cause right heart failure. There are a number of other rare pulmonary manifestations of histoplasmosis.

Histoplasmosis, like blastomycosis, may disseminate haematogenously to infect internal organs and tissues, but it does so in a very low proportion of cases, and half or more of these dissemination cases involve immunocompromisation. Unlike blastomycosis, histoplasmosis is a recognized AIDS-defining illness in people with HIV infection; disseminated histoplasmosis affects approximately 5% of AIDS patients with CD4+ cell counts <150 cells/µL in highly endemic areas.[21] The incidence of this condition dropped significantly after introduction of current anti-HIV therapies.[20] Other conditions very uncommonly associated with H. capsulatum include endocarditis and peritonitis.[7][22]

H. capsulatum appears to be strongly associated with the droppings of certain bird species as well as bats.[7] A mixture of these droppings and certain soil types is particularly conducive to proliferation. In highly endemic areas there is a strong association with soil under and around chicken houses, and with areas where soil or vegetation has become heavily contaminated with faecal material deposited by flocking birds such as starlings and blackbirds. Bird roosting areas that are Histoplasma-free appear to be lower in nitrogen, phosphorus, organic matter and moisture than contaminated roosting areas.[7] The guano of gulls and other colonially nesting water-associated birds is rarely connected to histoplasmosis.[23] Bat dwellings, including caves, attics and hollow trees, are classic H. capsulatum habitats.[7][22]

Histoplasmosis outbreaks are typically associated with cleaning guano accumulations or clearing guano-covered vegetation, or with exploration of bat caves. In addition, however, outbreaks may be associated with wind-blown dust liberated by construction projects in endemic areas: a classic outbreak is one associated with intense construction activity, including subway construction, in Montreal in 1963.[24]

As with blastomycosis, a good understanding of the precise ecological affinities of H. capsulatum is greatly complicated by the difficulty of isolating the fungus directly from nature. Again, the mouse passage procedure originally devised by Emmons[25] must be used. A direct PCR technique for detection of H. capsulatum in soil has been published.[26] H. capsulatum appears particularly likely to cause clinical disease in young children, persons working in sites contaminated by conducive bird or bat droppings, persons exposed to construction dust raised from contaminated sites, immunocompromised patients, and emphysema sufferers. Elimination of the agent from contaminated soils typically involves the use of toxic fumigants with limited success.[27]

In 1905, Samuel Taylor Darling serendipitously identified a protozoan-like microorganism in an autopsy specimen while trying to understand malaria, which was prevalent during the construction of the Panama Canal. He named this microorganism Histoplasma capsulatum because it invaded the cytoplasm (plasma) of histiocyte-like cells (Histo) and had a refractive halo mimicking a capsule (capsulatum), a misnomer. [28]

Histopathology of Histoplasma capsulatum, GMS stain, showing narrow budding yeast

Histoplasma (bright red, small, circular). PAS diastase stain

Histoplasma in a granuloma. PAS diastase stain.

Histoplasma in a granuloma. GMS stain.

Histoplasma capsulatum is a species of dimorphic fungus. Its sexual form is called Ajellomyces capsulatus. It can cause pulmonary and disseminated histoplasmosis.

H. capsulatum is "distributed worldwide, except in Antarctica, but most often associated with river valleys" and occurs chiefly in the "Central and Eastern United States" followed by "Central and South America, and other areas of the world". It is most prevalent in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. It was discovered by Samuel Taylor Darling in 1906.