en

names in breadcrumbs

Dişli balinalar (lat. Odontoceti)— balinakimilər dəstəsindən suda yaşayan məməlilər yarımdəstəsi.

Uzunluğu 1,2 m-dən 20 m-ə qədərdir. Dişsiz balinalar-dan fərqli olaraq 1-dən 240-dək dişi olur. Başının təpə hissəsində bir burun dəliyi var. Alt çənə qısa olub ön tərəfdən bitişmişdir. Dişli balinalar oriyentasiyanı exolokasiya ilə təyin edir. Hava kisələri sistemi olan exolokasiya aparatının yaranması kəllənin asimmetriyasına səbəb olmuşdur. Dişli balinalar çox yaxşı eşidir və səs siqnallarını qəbul edir. Burun kanalı ilə əlaqədar olan səs orqanı yaxşı inkişaf etmişdir. Dişli balinalar Sakit və Atlantik okeanlarının dənizlərində yayılmışdır.

Cinsi yetkinliyə 2—6 yaşında çatır. Balıqlar, başıayaqlı molyusklar və xərçəngkimilərlə qidalanır. İnsan üçün faydalı olanları kaşalot, afalina, əsl delfinlər, dəniz donuzu, ağ delfin, orka və s.-dir. Piyindən (texniki məqsədlə), həmçinin spermasetindən və ətindən istifadə olunur. Bir çox növləri kəskin surətdə azalmışdır. Bəzi dişli balinalar mühafizə edilir.

Dişli balinalar (lat. Odontoceti)— balinakimilər dəstəsindən suda yaşayan məməlilər yarımdəstəsi.

Uzunluğu 1,2 m-dən 20 m-ə qədərdir. Dişsiz balinalar-dan fərqli olaraq 1-dən 240-dək dişi olur. Başının təpə hissəsində bir burun dəliyi var. Alt çənə qısa olub ön tərəfdən bitişmişdir. Dişli balinalar oriyentasiyanı exolokasiya ilə təyin edir. Hava kisələri sistemi olan exolokasiya aparatının yaranması kəllənin asimmetriyasına səbəb olmuşdur. Dişli balinalar çox yaxşı eşidir və səs siqnallarını qəbul edir. Burun kanalı ilə əlaqədar olan səs orqanı yaxşı inkişaf etmişdir. Dişli balinalar Sakit və Atlantik okeanlarının dənizlərində yayılmışdır.

Cinsi yetkinliyə 2—6 yaşında çatır. Balıqlar, başıayaqlı molyusklar və xərçəngkimilərlə qidalanır. İnsan üçün faydalı olanları kaşalot, afalina, əsl delfinlər, dəniz donuzu, ağ delfin, orka və s.-dir. Piyindən (texniki məqsədlə), həmçinin spermasetindən və ətindən istifadə olunur. Bir çox növləri kəskin surətdə azalmışdır. Bəzi dişli balinalar mühafizə edilir.

Ar morviled dantek eo ar bronneged a ya d'ober an isurzhiad Odontoceti, en o zouez emañ an delfined, ar skoazog pe ar c'hwezhered da skouer.

Disheñvel int diouzh an isurzhiad all (ar morviled fanoliek) dre ma'z eus dent en o genoù.

Ar morviled dantek eo ar bronneged a ya d'ober an isurzhiad Odontoceti, en o zouez emañ an delfined, ar skoazog pe ar c'hwezhered da skouer.

Disheñvel int diouzh an isurzhiad all (ar morviled fanoliek) dre ma'z eus dent en o genoù.

Els odontocets (Odontoceti, del llatí; gran animal marí i del grec Ketus; monstre marí) són un ordre de cetacis que es diferencien dels Mysticeti per tenir dentadura, un sol orifici nasal, un crani asimètric i un front voluminós a causa de la presència de l'òrgan utilitzat en l'ecolocalització.

A diferència dels misticets, els odontocetis són cetacis que tenen una forta dentadura, presentant una dentadura "homodonta". Aquesta dentadura, és utilitzada com a caràcter taxonòmic, ja que cada espècie té un nombre de dents diferents.

Els seus principals aliments són els calamars, pops, crustacis, peixos i inclòs mamífers com lleons marins i ocells aquàtics. Per exemple els catxalots s'alimenten principalment de calamars gegants.

En algunes espècies la femella és més gran que el mascle. Els període de gestació entre 14 i 18 mesos segons l'espècie. Generalment té una sola cria en cada part. La cria és alletada entre 1 i 2 anys de vida i s'està amb la seva mare al voltant de 5 a 10 anys. Les femelles crien cada 2 o 3 anys.

Entre els gèneres extints de classificació incerta hi ha Chilcacetus, del Miocè inferior del Perú.

Els odontocets (Odontoceti, del llatí; gran animal marí i del grec Ketus; monstre marí) són un ordre de cetacis que es diferencien dels Mysticeti per tenir dentadura, un sol orifici nasal, un crani asimètric i un front voluminós a causa de la presència de l'òrgan utilitzat en l'ecolocalització.

Ozubení (Odontoceti) je podřád kytovců. Pro zástupce tohoto podřádu je charakteristické, že mají zuby, což je jeden ze znaků, jímž se odlišují od kosticovců, kteří mají kostice. Ozubení jsou aktivní lovci, živí se rybami, chobotnicemi a někdy mořskými savci.

Ozubení mají jednu nozdru na temeni hlavy (zatímco kosticovci mají dvě). Až na vorvaňovité jsou ozubení menší než kosticovci. Zuby se mezi druhy značně liší. Může jich být spousta, jako u některých delfínů, kteří mají v tlamě více než 100 zubů. Další extrémy pozorujeme u narvalovitých s jejich dlouhým klem a u téměř bezzubých vorvaňovcovitých se zvlaštními zuby pouze u samců. Ne všechny druhy používají své zuby ke krmení. Například vorvaňovití používají své zuby k předvádění se a k agresivním útokům.

Hlasové projevy jsou u ozubených velmi důležité. Jsou schopni vydávat různé zvuky určené ke komunikaci, ale také dokážou využít ultrazvuk k echolokaci.

Většina ozubených plave svižně. Menší druhy se občas svezou na vlnách, vyvolaných projíždející lodí. Delfíni jsou známi svými akrobatickými výskoky z vody.

Většinou žijí ozubení ve skupinách o tuctech kusů. Tyto malé skupinky se příležitostně spojují a vytvářejí větší agregace až o tisíci velrybách. Ozubení jsou schopni složitých vztahů, například týmového lovu. Některé druhy v zajetí prokazují velký potenciál pro učení se, z tohoto důvodu jsou považování za jedny z nejinteligentnějších zvířat.

Ozubení (Odontoceti) je podřád kytovců. Pro zástupce tohoto podřádu je charakteristické, že mají zuby, což je jeden ze znaků, jímž se odlišují od kosticovců, kteří mají kostice. Ozubení jsou aktivní lovci, živí se rybami, chobotnicemi a někdy mořskými savci.

Tandhvaler (Odontoceti) er en underorden af hvaler der er kendetegnet ved at have tænder, i modsætning til den anden gruppe af hvaler, bardehvalerne, der ikke har tænder. De fleste tandhvaler har mange relativt ens, spidse tænder i munden, mens næbhvalerne kun har to i underkæben. Tandhvalerne er alle rovdyr og lever især af fisk og blæksprutter, mens de større arter også kan tage større bytte som sæler, hajer eller kæmpeblæksprutter. Typisk for tandhvaler er at de kun har et enkelt blåsthul oven på hovedet, i modsætning til bardehvaler som har to. Alle tandhvaler formodes at bruge biosonar, dvs. de kan orientere sig og fange bytte ved hjælp af ekkolokalisering. En lang række anatomiske specialiseringer er knyttet til biosonaren, bl.a. det asymmetriske kranium, den fedtfyldte melon forrest på hovedet og et kompliceret system af luftblindsække i forbindelse med næseborene. Ingen af disse strukturer findes hos noget andet pattedyr og understøtter at Odontoceti er en monofyletisk gruppe[1], dvs. de nedstammer alle fra en fælles stamform, der havde biosonar.

Tandhvaler inddeles normalt i 7 familier, med enkelte eksempler angivet under hver familie:

Tandhvaler (Odontoceti) er en underorden af hvaler der er kendetegnet ved at have tænder, i modsætning til den anden gruppe af hvaler, bardehvalerne, der ikke har tænder. De fleste tandhvaler har mange relativt ens, spidse tænder i munden, mens næbhvalerne kun har to i underkæben. Tandhvalerne er alle rovdyr og lever især af fisk og blæksprutter, mens de større arter også kan tage større bytte som sæler, hajer eller kæmpeblæksprutter. Typisk for tandhvaler er at de kun har et enkelt blåsthul oven på hovedet, i modsætning til bardehvaler som har to. Alle tandhvaler formodes at bruge biosonar, dvs. de kan orientere sig og fange bytte ved hjælp af ekkolokalisering. En lang række anatomiske specialiseringer er knyttet til biosonaren, bl.a. det asymmetriske kranium, den fedtfyldte melon forrest på hovedet og et kompliceret system af luftblindsække i forbindelse med næseborene. Ingen af disse strukturer findes hos noget andet pattedyr og understøtter at Odontoceti er en monofyletisk gruppe, dvs. de nedstammer alle fra en fælles stamform, der havde biosonar.

Die Zahnwale (Odontoceti) sind eine der beiden Unterordnungen der Wale (Cetacea). Sie zeichnen sich vor allem durch das namensgebende Vorhandensein von Zähnen aus, deren Form und Anzahl jedoch innerhalb der Gruppe stark variiert. Außerdem besitzen sie im Gegensatz zu den Bartenwalen (Mysticeti) nur ein, nicht zwei Blaslöcher. Zahnwale sind carnivor und ernähren sich hauptsächlich von Fischen, Tintenfischen und in manchen Fällen von anderen Meeressäugern.

Die bekannteste und gleichzeitig artenreichste Familie der Zahnwale sind die Delfine.

Fast alle Zahnwale sind sehr viel kleiner als die Bartenwale. Nur der Pottwal wird zu den Großwalen gezählt. Die übrigen Arten sind klein bis mittelgroß. Weiterhin unterscheiden sich Zahnwale von Bartenwalen dadurch, dass sie nur ein einziges Blasloch haben.

Die Zähne sind bei den verschiedenen Arten ganz unterschiedlich ausgeprägt. Viele Zahnwale besitzen sehr viele Zähne, bis zu 100 bei einigen Delfinen. Der Narwal hat dagegen einen langen Stoßzahn und bei den fast zahnlosen Schnabelwalen haben die Männchen bizarr geformte Zähne. Bei den Zahnwalen ist es relativ einfach, das Alter zu bestimmen. Jedes Jahr bildet sich auf ihren Zähnen eine neue Schicht, was in etwa den Jahresringen eines Baumes entspricht. Den ältesten Zahnwal, den man bisher fand, war ein Pottwal mit 70 Ringen. Bei den großen Tümmlern geht man von einem Spitzenalter von 40 Jahren aus.

Die meisten Zahnwale sind schnelle Schwimmer. Die kleinen Arten reiten gelegentlich auf Wellen, etwa den Bugwellen von Schiffen. Besonders häufig sind dabei Delfine wie der Spinner anzutreffen, die auch bekannt für ihre akrobatischen Sprünge sind.

Lautgebungen spielen bei Zahnwalen eine große Rolle. Neben zahlreichen Pfeiflauten zur Kommunikation beherrschen sie den Einsatz von Ultraschalltönen für die Echoortung. Dieser Sinn ist insbesondere bei der Jagd von großer Bedeutung.

Meist leben Zahnwale in Gruppen von einigen bis etwa einem Dutzend Tieren. Diese so genannten Schulen können sich vorübergehend zu größeren Ansammlungen bis zu tausenden Walen zusammenschließen. Zahnwale sind zu komplexen Leistungen in der Lage, etwa zur Kooperation bei der Jagd auf Fischschwärme. In Gefangenschaft beweisen einige Arten eine hohe Lernfähigkeit, weswegen sie von Zoologen zu den intelligentesten Tieren gezählt werden.

Delfine (Delphinidae)

Gründelwale (Monodontidae)

Schweinswale (Phocoenidae)

La-Plata-Delfin (Pontoporiidae)

Amazonas-Flussdelfine (Iniidae)

Chinesischer Flussdelfin (Lipotidae)

Schnabelwale (Ziphiidae)

Gangesdelfine (Platanistidae)

Zwergpottwale (Kogiidae)

Pottwale (Physeteridae)

Man unterteilt die rezenten Zahnwale heute in zehn Familien:[2]

Es gibt mehrere Ansätze, diese Familien zu Überfamilien zusammenzufassen. Als gesichert gilt allein, dass die Familien der Delfine, Schweinswale und Gründelwale miteinander verwandt sind. Sie werden manchmal als Delfinartige (Delphinoidea) zusammengefasst. Dagegen war die Systematik der Flussdelfine umstritten. Manchmal wurden sie in einer Familie zusammengefasst, manchmal als lediglich konvergent entwickelte Tiere in vier Familien unterteilt. Nach molekulargenetischen Untersuchungen ist die Sonderstellung der Gangesdelfine und die Verwandtschaft der übrigen drei Gattungen (Inia, Pontoporia und Lipotes) wahrscheinlich. Pottwale und Zwergpottwale sind ursprüngliche Familien der Zahnwale und stehen den übrigen Familien als Schwestergruppe gegenüber.[1]

Der Pottwal wurde lange Zeit für die Industrie intensiv gejagt, vor allem wegen des früher für die Parfümherstellung eingesetzten Ambra. Während auf einige Kleinwale wie den Grindwal noch heute Jagd gemacht wird, sind die meisten Arten hauptsächlich durch den Beifang bedroht. Insbesondere beim Thunfischfang ertrinken Tausende von Delfinen in den Netzen.

Die Haltung von Kleinwalen, zumeist Großen Tümmlern, Schwertwalen und Belugas, ist eine große Attraktion für Ozeanarien und Zoos. Sie ist jedoch wegen des großen Platzbedarfs der Meeressäuger umstritten. Das Gleiche gilt für den Einsatz in der Delfintherapie.[3][4]

Die Zahnwale (Odontoceti) sind eine der beiden Unterordnungen der Wale (Cetacea). Sie zeichnen sich vor allem durch das namensgebende Vorhandensein von Zähnen aus, deren Form und Anzahl jedoch innerhalb der Gruppe stark variiert. Außerdem besitzen sie im Gegensatz zu den Bartenwalen (Mysticeti) nur ein, nicht zwei Blaslöcher. Zahnwale sind carnivor und ernähren sich hauptsächlich von Fischen, Tintenfischen und in manchen Fällen von anderen Meeressäugern.

Die bekannteste und gleichzeitig artenreichste Familie der Zahnwale sind die Delfine.

Balenat me dhëmbë (emri sistematik Odontoceti) formojnë një nënrend të rendit Cetacea, ku përfshihen kashalotët,balenat me sqep, delfinët dhe derrat e detit. Siç sugjeron dhe emri, ky nënrend veçohet nga prania e dhëmbëve, jo e mustaqeve të balenës sikurse tek balenat tjera. Shtatëdhjetë e tre lloje të balenave me dhëmbë janë përshkruar. Mendohet të jenë ndarë nga balenat me mustaqe nënrendit Mysticeti, rreth 34 milionë vjet më parë. Balenat dhe delfinët, grupet parafiletike të cetaceve, si dhe marsuinët, i përkasin degës Cetartiodactyla, së bashku me dy thundrakët me majë; lloji i tyre më i afërt i gjallë është kali i Nilit, me të cilin u ndanë rreth 40 milionë vjet më parë.

Balenat me dhëmbë (emri sistematik Odontoceti) formojnë një nënrend të rendit Cetacea, ku përfshihen kashalotët,balenat me sqep, delfinët dhe derrat e detit. Siç sugjeron dhe emri, ky nënrend veçohet nga prania e dhëmbëve, jo e mustaqeve të balenës sikurse tek balenat tjera. Shtatëdhjetë e tre lloje të balenave me dhëmbë janë përshkruar. Mendohet të jenë ndarë nga balenat me mustaqe nënrendit Mysticeti, rreth 34 milionë vjet më parë. Balenat dhe delfinët, grupet parafiletike të cetaceve, si dhe marsuinët, i përkasin degës Cetartiodactyla, së bashku me dy thundrakët me majë; lloji i tyre më i afërt i gjallë është kali i Nilit, me të cilin u ndanë rreth 40 milionë vjet më parë.

Khí-keng (ha̍k-miâ Odontoceti) sī Cetacea ba̍k ē-kha ê a-ba̍k, sêng-oân pau-koah só͘-ū ê hái-ti kap pō͘-hūn ê hái-ang. In hām Mysticeti a-ba̍k ê chéng chha tī ū chhùi-khí bô keng-chhiu. In-ūi án-ne, khí-keng sī chek-ke̍k lia̍h-chia̍h ê tōng-bu̍t, bo̍k-phiau pau-koah hî-á, ba̍k-cha̍t, ū sî-chūn sīm-chì hái--ni̍h kî-thaⁿ ê chhī-leng tōng-bu̍t.

Ang mga may ngipin na buhakag (sistematikong pangalan Odontoceti) ay isang parvorder ng cetaceans na kinabibilangan ng mga lumba-lumba, porpoise, at lahat ng iba pang mga buhakag na may mga ngipin, tulad ng beaked whale at sperm whale. Ang pitumpu't tatlong espesye ng may balbas na buhakag (tinatawag ding odontocetes) ay inilarawan. Ang mga ito ay isa sa dalawang mga grupo ng pamumuhay ng cetacean, ang iba ay ang baleen whale (Mysticeti), na may baleen sa halip ng mga ngipin. Ang dalawang grupo ay naisip na nai-diver sa paligid ng 34 milyong taon na ang nakakaraan (mya).

![]() Ang lathalaing ito ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

Ang lathalaing ito ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito. ![]() Ang lathalaing ito na tungkol sa Mamalya ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

Ang lathalaing ito na tungkol sa Mamalya ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

Odontocèts

Los odontocèts (Odontoceti), o cetacèus de dents (balenas de dents) constituisson un dels dos sosòrdres dels cetacèus amb los misticèts (o balenas de fanons).

Los cetacèus d'aqueste grop d'espècias an de dents, mentre que los misticèts son de cetacèus de fanons. Los odontocèts son los sols animals amb las ratapenadas e cèrtas musaranhas capables d'ecolocacion al mejan d'ultrasons : localizan lors predas e s'orientan en analizant los ressons dels sons qu'emeton. Una foncion que s'aparenta al sistèma del sonar. Lo sosòrdre dels odontocèts compren las diferentas espècias de belugas, de cachalots, d'òrcas, de dalfins, de marsoins, de narvals e de globicefals.

Lo sosòrdre conten 6 familhas :

Mai 4 familhas opcionalas:

Los odoncèts son carnivòrs. Lors dents lor servisson pas a mastegar mas a atrapar lors predas, que se compausan de peisses, de calamars, de molluscas e de còps d'autres cetacèus pels grands predators odontocèts coma los òrcas. Cèrtas espècias coma las balenas de bècs o encara los cachalòts an de dents pas que sus la maissa inferiora.

Coma totes los mamifèrs marins, los odoncèts an de polmons e devon periodicament alenar a la superfícia. Los odontocèts an pas qu'un sol event çò que los distinguís de las balenas de fanons.

Odontocèts

Los odontocèts (Odontoceti), o cetacèus de dents (balenas de dents) constituisson un dels dos sosòrdres dels cetacèus amb los misticèts (o balenas de fanons).

Los cetacèus d'aqueste grop d'espècias an de dents, mentre que los misticèts son de cetacèus de fanons. Los odontocèts son los sols animals amb las ratapenadas e cèrtas musaranhas capables d'ecolocacion al mejan d'ultrasons : localizan lors predas e s'orientan en analizant los ressons dels sons qu'emeton. Una foncion que s'aparenta al sistèma del sonar. Lo sosòrdre dels odontocèts compren las diferentas espècias de belugas, de cachalots, d'òrcas, de dalfins, de marsoins, de narvals e de globicefals.

Tannhvalir (Odontoceti) eru hvalir, sum hava tenn. Dømi um tannhvalir eru: grindahvalur og mastrahvalur/bóghvítuhvalur, augustur og nísa.

Tishli kitlar (Odontoceti) - kitlarning kenja turkumi. Tanasining uz. 1,2–20 m. Tishli kitlar tishsiz kitlaraan 1—240 tagacha tishi boʻlishi bilan farq qiladi. Burun teshigi bitta. Bosh suyagining yuz qismi asimmetrik boʻlib, pastki jagʻ kalla suyagidan kalta, uning oldingi qismi harakatsiz birikkan. Tishli kitlarning asosiy moʻljal olish (chamalash) usuli — exolokatsiya. Eshitish va tovush organlari yaxshi rivojlangan. Exolokatsiya va eshitish orqali oʻzaro bogʻlanadi, ozigʻini topadi va suv ostida moʻljal oladi. Tishli kitlar murakkab tovush signallaridan ham foydalanadi. 74 turi va 4 oilasi: kashalotlar, oʻtkir tumshuqlilar, daryo delfinlari, delfinlar bor. Koʻpchiligi gala boʻlib yashaydi. Deyarli hamma dengiz va okeanlarda tarqalgan. 2—6 yoshda jinsiy yetiladi. Baliq, bosh oyokli mollyuskalar va qisqichbaqasimonlar bilan oziklanadi. Baʼzi turlari ovlanadi. Kashalot, kosatka, oq biqinli delfin va boshqalarning yogʻi, spermatseti hamda goʻshtidan foydalaniladi. Koʻpgina turlarining soni keskin kamaygan. Bir qancha turlari Xalqaro Qizil kitobga kiritilgan.

The tuithed whauls (systematic name Odontoceti) furm a suborder o the cetaceans, includin sperm whauls, beaked whales, dowphins, an ithers. As the name suggests, the suborder is chairacterised bi the presence o teeth raither than the baleen o ither whauls.

Tuswaaler (Odontoceti) san ian faan tau onerkategoriin faan a waaler (Cetacea). Det ööder onerkategorii san a biardenwaaler (Mysticeti).

Tu a tuswaaler hiar tjiin familin:

Tuswaaler (Odontoceti) san ian faan tau onerkategoriin faan a waaler (Cetacea). Det ööder onerkategorii san a biardenwaaler (Mysticeti).

The toothed whales (also called odontocetes, systematic name Odontoceti) are a parvorder of cetaceans that includes dolphins, porpoises, and all other whales possessing teeth, such as the beaked whales and sperm whales. 73 species of toothed whales are described. They are one of two living groups of cetaceans, the other being the baleen whales (Mysticeti), which have baleen instead of teeth. The two groups are thought to have diverged around 34 million years ago (mya).

Toothed whales range in size from the 1.4 m (4.6 ft) and 54 kg (119 lb) vaquita to the 20 m (66 ft) and 55 t (61-short-ton) sperm whale. Several species of odontocetes exhibit sexual dimorphism, in that there are size or other morphological differences between females and males. They have streamlined bodies and two limbs that are modified into flippers. Some can travel at up to 20 knots. Odontocetes have conical teeth designed for catching fish or squid. They have well-developed hearing that is well adapted for both air and water, so much so that some can survive even if they are blind. Some species are well adapted for diving to great depths. Almost all have a layer of fat, or blubber, under the skin to keep warm in the cold water, with the exception of river dolphins.

Toothed whales consist of some of the most widespread mammals, but some, as with the vaquita, are restricted to certain areas. Odontocetes feed largely on fish and squid, but a few, like the orca, feed on mammals, such as pinnipeds. Males typically mate with multiple females every year, making them polygynous. Females mate every two to three years. Calves are typically born in the spring and summer, and females bear the responsibility for raising them, but more sociable species rely on the family group to care for calves. Many species, mainly dolphins, are highly sociable, with some pods reaching over a thousand individuals.

Once hunted for their products, cetaceans are now protected by international law. Some species are attributed with high levels of intelligence. At the 2012 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, support was reiterated for a cetacean bill of rights, listing cetaceans as nonhuman persons. Besides whaling and drive hunting, they also face threats from bycatch and marine pollution. The baiji, for example, is considered functionally extinct by the IUCN, with the last sighting in 2004, due to heavy pollution to the Yangtze River. Whales occasionally feature in literature and film, as in the great white sperm whale of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick. Small odontocetes, mainly dolphins, are kept in captivity and trained to perform tricks. Whale watching has become a form of tourism around the world.

The tube in the head, through which this kind fish takes its breath and spitting water, located in front of the brain and ends outwardly in a simple hole, but inside it is divided by a downward bony septum, as if it were two nostrils; but underneath it opens up again in the mouth in a void.

–John Ray, 1671, the earliest description of cetacean airways

In Aristotle's time, the fourth century BC, whales were regarded as fish due to their superficial similarity. Aristotle, however, could already see many physiological and anatomical similarities with the terrestrial vertebrates, such as blood (circulation), lungs, uterus, and fin anatomy. His detailed descriptions were assimilated by the Romans, but mixed with a more accurate knowledge of the dolphins, as mentioned by Pliny the Elder in his Natural history. In the art of this and subsequent periods, dolphins are portrayed with a high-arched head (typical of porpoises) and a long snout. The harbor porpoise is one of the most accessible species for early cetologists, because it could be seen very close to land, inhabiting shallow coastal areas of Europe. Many of the findings that apply to all cetaceans were therefore first discovered in the porpoises.[2] One of the first anatomical descriptions of the airways of the whales on the basis of a harbor porpoise dates from 1671 by John Ray. It nevertheless referred to the porpoise as a fish.[3][4]

Belugas, narwhals (Monodontidae) ![]()

Porpoises (Phocoenidae) ![]()

Oceanic dolphins (Delphinidae) ![]()

Beaked whales (Ziphiidae) ![]()

South Asian river dolphins (Platanistidae)

Dwarf sperm whales (Kogiidae) ![]()

Sperm whales (Physeteridae) ![]()

Toothed whales, as well as baleen whales, are descendants of land-dwelling mammals of the artiodactyl order (even-toed ungulates). They are closely related to the hippopotamus, sharing a common ancestor that lived around 54 million years ago (mya).[6] The primitive cetaceans, or archaeocetes, first took to the sea approximately 49 mya and became fully aquatic by 5–10 million years later.[7] The ancestors of toothed whales and baleen whales diverged in the early Oligocene. This was due to a change in the climate of the southern oceans that affected where the environment of the plankton that these whales ate.[8]

The adaptation of echolocation and enhanced fat synthesis in blubber occurred when toothed whales split apart from baleen whales, and distinguishes modern toothed whales from fully aquatic archaeocetes. This happened around 34 mya.[9] Unlike toothed whales, baleen whales do not have wax ester deposits nor branched fatty chain acids in their blubber. Thus, more recent evolution of these complex blubber traits occurred after baleen whales and toothed whales split, and only in the toothed whale lineage.[10]

[11][12] Modern toothed whales do not rely on their sense of sight, but rather on their sonar to hunt prey. Echolocation also allowed toothed whales to dive deeper in search of food, with light no longer necessary for navigation, which opened up new food sources.[13][14] Toothed whales (Odontocetes) echolocate by creating a series of clicks emitted at various frequencies. Sound pulses are emitted through their melon-shaped foreheads, reflected off objects, and retrieved through the lower jaw. Skulls of Squalodon show evidence for the first hypothesized appearance of echolocation.[15] Squalodon lived from the early to middle Oligocene to the middle Miocene, around 33-14 mya. Squalodon featured several commonalities with modern Odontocetes. The cranium was well compressed, the rostrum telescoped outward (a characteristic of the modern parvorder Odontoceti), giving Squalodon an appearance similar to that of modern toothed whales. However, it is thought unlikely that squalodontids are direct ancestors of living dolphins.[16]

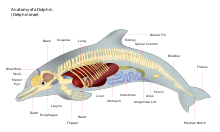

Toothed whales have torpedo-shaped bodies with usually inflexible necks, limbs modified into flippers, nonexistent external ear flaps, a large tail fin, and bulbous heads (with the exception of sperm whales). Their skulls have small eye orbits, long beaks (with the exception sperm whales), and eyes placed on the sides of their heads. Toothed whales range in size from the 4.5 ft (1.4 m) and 120 lb (54 kg) vaquita to the 20 m (66 ft) and 55 t (61-short-ton) sperm whale. Overall, they tend to be dwarfed by their relatives, the baleen whales (Mysticeti). Several species have sexual dimorphism, with the females being larger than the males. One exception is with the sperm whale, which has males larger than the females.[17][18]

Odontocetes, such as the sperm whale, possess teeth with cementum cells overlying dentine cells. Unlike human teeth, which are composed mostly of enamel on the portion of the tooth outside of the gum, whale teeth have cementum outside the gum. Only in larger whales, where the cementum is worn away on the tip of the tooth, does enamel show.[17] Except for the sperm whale, most toothed whales are smaller than the baleen whales. The teeth differ considerably among the species. They may be numerous, with some dolphins bearing over 100 teeth in their jaws. At the other extreme are the narwhals with their single long tusks and the almost toothless beaked whales with tusk-like teeth only in males.[19] Not all species are believed to use their teeth for feeding. For instance, the sperm whale likely uses its teeth for aggression and showmanship.[17]

Breathing involves expelling stale air from their one blowhole, forming an upward, steamy spout, followed by inhaling fresh air into the lungs. Spout shapes differ among species, which facilitates identification. The spout only forms when warm air from the lungs meets cold air, so it does not form in warmer climates, as with river dolphins.[17][20][21]

Almost all cetaceans have a thick layer of blubber, with the exception of river dolphins. In species that live near the poles, the blubber can be as thick as 11 in (28 cm). This blubber can help with buoyancy, protection to some extent as predators would have a hard time getting through a thick layer of fat, energy for fasting during leaner times, and insulation from the harsh climates. Calves are born with only a thin layer of blubber, but some species compensate for this with thick lanugos.[17][22]

Toothed whales have also evolved the ability to store large amounts of wax esters in their adipose tissue as an addition to or in complete replacement of other fats in their blubber. They can produce isovaleric acid from branched chain fatty acids (BCFA). These adaptations are unique, are only in more recent, derived lineages and were likely part of the transition for species to become deeper divers as the families of toothed whales (Physeteridae, Kogiidae, and Ziphiidae) that have the highest quantities of wax esters and BCFAs in their blubber are also the species that dive the deepest and for the longest amount of time.[10]

Toothed whales have a two-chambered stomach similar in structure to terrestrial carnivores. They have fundic and pyloric chambers.[23]

Cetaceans have two flippers on the front, and a tail fin. These flippers contain four digits. Although toothed whales do not possess fully developed hind limbs, some, such as the sperm whale, possess discrete rudimentary appendages, which may contain feet and digits. Toothed whales are fast swimmers in comparison to seals, which typically cruise at 5–15 knots, or 9–28 km/h (5.6–17.4 mph); the sperm whale, in comparison, can travel at speeds of up to 35 km/h (22 mph). The fusing of the neck vertebrae, while increasing stability when swimming at high speeds, decreases flexibility, rendering them incapable of turning their heads; river dolphins, however, have unfused neck vertebrae and can turn their heads. When swimming, toothed whales rely on their tail fins to propel them through the water. Flipper movement is continuous. They swim by moving their tail fin and lower body up and down, propelling themselves through vertical movement, while their flippers are mainly used for steering. Some species log out of the water, which may allow them to travel faster. Their skeletal anatomy allows them to be fast swimmers. Most species have a dorsal fin.[17][22]

Most toothed whales are adapted for diving to great depths, porpoises are one exception. In addition to their streamlined bodies, they can slow their heart rate to conserve oxygen; blood is rerouted from tissue tolerant of water pressure to the heart and brain among other organs; haemoglobin and myoglobin store oxygen in body tissue; and they have twice the concentration of myoglobin than haemoglobin. Before going on long dives, many toothed whales exhibit a behaviour known as sounding; they stay close to the surface for a series of short, shallow dives while building their oxygen reserves, and then make a sounding dive.[24]

Toothed whale eyes are relatively small for their size, yet they do retain a good degree of eyesight. As well as this, the eyes are placed on the sides of its head, so their vision consists of two fields, rather than a binocular view as humans have. When a beluga surfaces, its lenses and corneas correct the nearsightedness that results from the refraction of light; they contain both rod and cone cells, meaning they can see in both dim and bright light. They do, however, lack short wavelength-sensitive visual pigments in their cone cells, indicating a more limited capacity for colour vision than most mammals.[25] Most toothed whales have slightly flattened eyeballs, enlarged pupils (which shrink as they surface to prevent damage), slightly flattened corneas, and a tapetum lucidum; these adaptations allow for large amounts of light to pass through the eye, and, therefore, a very clear image of the surrounding area. In water, a whale can see around 10.7 m (35 ft) ahead of itself, but they have a smaller range above water. They also have glands on the eyelids and outer corneal layer that act as protection for the cornea.[17][26]: 505–519

The olfactory lobes are absent in toothed whales, and unlike baleen whales, they lack the vomeronasal organ, suggesting they have no sense of smell.[26]: 481–505

Toothed whales are not thought to have a good sense of taste, as their taste buds are atrophied or missing altogether. However, some dolphins have preferences between different kinds of fish, indicating some sort of attachment to taste.[26]: 447–455

Toothed whales are capable of making a broad range of sounds using nasal airsacs located just below the blowhole. Roughly three categories of sounds can be identified: frequency-modulated whistles, burst-pulsed sounds, and clicks. Dolphins communicate with whistle-like sounds produced by vibrating connective tissue, similar to the way human vocal cords function,[27] and through burst-pulsed sounds, though the nature and extent of that ability is not known. The clicks are directional and are used for echolocation, often occurring in a short series called a click train. The click rate increases when approaching an object of interest. Toothed whale biosonar clicks are amongst the loudest sounds made by marine animals.[28]

The cetacean ear has specific adaptations to the marine environment. In humans, the middle ear works as an impedance equalizer between the outside air's low impedance and the cochlear fluid's high impedance. In whales, and other marine mammals, no great difference exists between the outer and inner environments. Instead of sound passing through the outer ear to the middle ear, whales receive sound through the throat, from which it passes through a low-impedance, fat-filled cavity to the inner ear.[29] The ear is acoustically isolated from the skull by air-filled sinus pockets, which allow for greater directional hearing underwater.[30] Odontocetes send out high-frequency clicks from an organ known as a melon. This melon consists of fat, and the skull of any such creature containing a melon will have a large depression. The melon size varies between species, the bigger it is, the more dependent they are on it. A beaked whale, for example, has a small bulge sitting on top of its skull, whereas a sperm whale's head is filled mainly with the melon.[17][26]: 1–19 [31][32] Odontocetes are well adapted to hear sounds at ultrasonic frequencies, as opposed to mysticetes who generally hear sounds within the range of infrasonic frequencies.[33]

Bottlenose dolphins have been found to have signature whistles unique to a specific individual. These whistles are used for dolphins to communicate with one another by identifying an individual. It can be seen as the dolphin equivalent of a name for humans.[34] Because dolphins are generally associated in groups, communication is necessary. Signal masking is when other similar sounds (conspecific sounds) interfere with the original acoustic sound.[35] In larger groups, individual whistle sounds are less prominent. Dolphins tend to travel in pods, in some instances including up to 600 members. [36]

Cetaceans are known to communicate and therefore are able to teach, learn, cooperate, scheme, and grieve.[37] The neocortex of many species of dolphins is home to elongated spindle neurons that, prior to 2007, were known only in hominids.[38] In humans, these cells are involved in social conduct, emotions, judgement, and theory of mind. Dolphin spindle neurons are found in areas of the brain homologous to where they are found in humans, suggesting they perform a similar function.[17]

Brain size was previously considered a major indicator of the intelligence of an animal. Since most of the brain is used for maintaining bodily functions, greater ratios of brain to body mass may increase the amount of brain mass available for more complex cognitive tasks. Allometric analysis indicates that mammalian brain size scales around the two-thirds or three-quarters exponent of the body mass. Comparison of a particular animal's brain size with the expected brain size based on such allometric analysis provides an encephalisation quotient that can be used as another indication of animal intelligence. Sperm whales have the largest brain mass of any animal on earth, averaging 8,000 cm3 (490 in3) and 7.8 kg (17 lb) in mature males, in comparison to the average human brain which averages 1,450 cm3 (88 in3) in mature males.[39] The brain to body mass ratio in some odontocetes, such as belugas and narwhals, is second only to humans.[40]

Dolphins are known to engage in complex play behaviour, which includes such things as producing stable underwater toroidal air-core vortex rings or "bubble rings". Two main methods of bubble ring production are: rapid puffing of a burst of air into the water and allowing it to rise to the surface, forming a ring, or swimming repeatedly in a circle and then stopping to inject air into the helical vortex currents thus formed. They also appear to enjoy biting the vortex rings, so that they burst into many separate bubbles and then rise quickly to the surface. Dolphins are known to use this method during hunting.[41] Dolphins have also been known to use tools. In Shark Bay, a population of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins put sponges on their beak to protect them from abrasions and sting ray barbs while foraging in the seafloor.[42] This behaviour is passed on from mother to daughter, and it is only observed in 54 female individuals.[43]

Self-awareness is seen, by some, to be a sign of highly developed, abstract thinking. Self-awareness, though not well-defined scientifically, is believed to be the precursor to more advanced processes like metacognitive reasoning (thinking about thinking) that are typical of humans. Research in this field has suggested that cetaceans, among others,[44] possess self-awareness.[45] The most widely used test for self-awareness in animals is the mirror test, in which a temporary dye is placed on an animal's body, and the animal is then presented with a mirror; then whether the animal shows signs of self-recognition is determined.[45] In 1995, Marten and Psarakos used television to test dolphin self-awareness.[46] They showed dolphins real-time footage of themselves, recorded footage, and another dolphin. They concluded that their evidence suggested self-awareness rather than social behavior. While this particular study has not been repeated since then, dolphins have since "passed" the mirror test.[45]

Dolphins are capable of making a broad range of sounds using nasal airsacs located just below the blowhole. Roughly three categories of sounds can be identified: frequency modulated whistles, burst-pulsed sounds and clicks. Dolphins communicate with whistle-like sounds produced by vibrating connective tissue, similar to the way human vocal cords function,[27] and through burst-pulsed sounds, though the nature and extent of that ability is not known. The clicks are directional and are for echolocation, often occurring in a short series called a click train. The click rate increases when approaching an object of interest. Dolphin echolocation clicks are amongst the loudest sounds made by marine animals.[47]

Bottlenose dolphins have been found to have signature whistles, a whistle that is unique to a specific individual. These whistles are used in order for dolphins to communicate with one another by identifying an individual. It can be seen as the dolphin equivalent of a name for humans.[34] These signature whistles are developed during a dolphin's first year; it continues to maintain the same sound throughout its lifetime.[48] An auditory experience influences the whistle development of each dolphin. Dolphins are able to communicate to one another by addressing another dolphin through mimicking their whistle. The signature whistle of a male bottlenose dolphin tends to be similar to that of his mother, while the signature whistle of a female bottlenose dolphin tends to be more identifying.[49] Bottlenose dolphins have a strong memory when it comes to these signature whistles, as they are able to relate to a signature whistle of an individual they have not encountered for over twenty years.[50] Research done on signature whistle usage by other dolphin species is relatively limited. The research on other species done so far has yielded varied outcomes and inconclusive results.[51][52][53][54]

Sperm whales can produce three specific vocalisations: creaks, codas, and slow clicks. A creak is a rapid series of high-frequency clicks that sounds somewhat like a creaky door hinge. It is typically used when homing in on prey.[55]: 135 A coda is a short pattern of 3 to 20 clicks that is used in social situations to identify one another (like a signature whistle), but it is still unknown whether sperm whales possess individually specific coda repertoires or whether individuals make codas at different rates.[56] Slow clicks are heard only in the presence of males (it is not certain whether females occasionally make them). Males make a lot of slow clicks in breeding grounds (74% of the time), both near the surface and at depth, which suggests they are primarily mating signals. Outside breeding grounds, slow clicks are rarely heard, and usually near the surface.[55]: 144

All whales are carnivorous and predatory. Odontocetes, as a whole, mostly feed on fish and cephalopods, and then followed by crustaceans and bivalves. All species are generalist and opportunistic feeders. Some may forage with other kinds of animals, such as other species of whales or certain species of pinnipeds.[22][57] One common feeding method is herding, where a pod squeezes a school of fish into a small volume, known as a bait ball. Individual members then take turns plowing through the ball, feeding on the stunned fish.[58] Coralling is a method where dolphins chase fish into shallow water to catch them more easily.[58] Orcas and bottlenose dolphins have also been known to drive their prey onto a beach to feed on it, a behaviour known as beach or strand feeding.[59][60] The shape of the snout may correlate with tooth number and thus feeding mechanisms. The narwhal, with its blunt snout and reduced dentition, relies on suction feeding.[61]

Sperm whales usually dive between 300 to 800 metres (980 to 2,620 ft), and sometimes 1 to 2 kilometres (3,300 to 6,600 ft), in search of food.[55]: 79 Such dives can last more than an hour.[55]: 79 They feed on several species, notably the giant squid, but also the colossal squid, octopuses, and fish like demersal rays, but their diet is mainly medium-sized squid.[55]: 43–55 Some prey may be taken accidentally while eating other items.[55]: 43–55 A study in the Galápagos found that squid from the genera Histioteuthis (62%), Ancistrocheirus (16%), and Octopoteuthis (7%) weighing between 12 and 650 grams (0.026 and 1.433 lb) were the most commonly taken.[62] Battles between sperm whales and giant squid or colossal squid have never been observed by humans; however, white scars are believed to be caused by the large squid. A 2010 study suggests that female sperm whales may collaborate when hunting Humboldt squid.[63]

The orca is known to prey on numerous other toothed whale species. One example is the false killer whale.[64] To subdue and kill whales, orcas continually ram them with their heads; this can sometimes kill bowhead whales, or severely injure them. Other times, they corral their prey before striking. They are typically hunted by groups of 10 or fewer orca, but they are seldom attacked by an individual. Calves are more commonly taken by orca, but adults can be targeted, as well.[65] Groups even attack larger cetaceans such as minke whales, gray whales, and rarely sperm whales or blue whales.[66][67] Other marine mammal prey species include nearly 20 species of seal, sea lion and fur seal.[68]

These cetaceans are targeted by terrestrial and pagophilic predators. The polar bear is well-adapted for hunting Arctic whales and calves. Bears are known to use sit-and-wait tactics, as well as active stalking and pursuit of prey on ice or water. Whales lessen the chance of predation by gathering in groups. This, however, means less room around the breathing hole as the ice slowly closes the gap. When out at sea, whales dive out of the reach of surface-hunting orca. Polar bear attacks on belugas and narwhals are usually successful in winter, but rarely inflict any damage in summer.[69]

For most of the smaller species of dolphins, only a few of the larger sharks, such as the bull shark, dusky shark, tiger shark, and great white shark, are a potential risk, especially for calves.[70] Dolphins can tolerate and recover from extreme injuries (including shark bites) although the exact methods used to achieve this are not known. The healing process is rapid and even very deep wounds do not cause dolphins to hemorrhage to death. Even gaping wounds restore in such a way that the animal's body shape is restored, and infection of such large wounds are rare.[71]

Toothed whales are fully aquatic creatures, which means their birth and courtship behaviours are very different from terrestrial and semiaquatic creatures. Since they are unable to go onto land to calve, they deliver their young with the fetus positioned for tail-first delivery. This prevents the calf from drowning either upon or during delivery. To feed the newborn, toothed whales, being aquatic, must squirt the milk into the mouth of the calf. Being mammals, they have mammary glands used for nursing calves; they are weaned around 11 months of age. This milk contains high amounts of fat which is meant to hasten the development of blubber; it contains so much fat, it has the consistency of toothpaste.[72] Females deliver a single calf, with gestation lasting about a year, dependency until one to two years, and maturity around seven to 10 years, all varying between the species. This mode of reproduction produces few offspring, but increases the survival probability of each one. Females, referred to as "cows", carry the responsibility of childcare, as males, referred to as "bulls", play no part in raising calves.

In orcas, false killer whales, short-finned pilot whales, narwhals, and belugas, there is an unusually long post-reproductive lifespan (menopause) in females. Older females, though unable to have their own children, play a key role in the rearing of other calves in the pod, and in this sense, given the costs of pregnancy especially at an advanced age, extended menopause is advantageous.[73][74]

The head of the sperm whale is filled with a waxy liquid called spermaceti. This liquid can be refined into spermaceti wax and sperm oil. These were much sought after by 18th-, 19th-, and 20th-century whalers. These substances found a variety of commercial applications, such as candles, soap, cosmetics, machine oil, other specialized lubricants, lamp oil, pencils, crayons, leather waterproofing, rustproofing materials, and many pharmaceutical compounds.[75] [76][77][78] Ambergris, a solid, waxy, flammable substance produced in the digestive system of sperm whales, was also sought as a fixative in perfumery.

Sperm whaling in the 18th century began with small sloops carrying only a pair of whaleboats (sometimes only one). As the scope and size of the fleet increased, so did the rig of the vessels change, as brigs, schooners, and finally ships and barks were introduced. In the 19th-century stubby, square-rigged ships (and later barks) dominated the fleet, being sent to the Pacific (the first being the British whaleship Emilia, in 1788),[79] the Indian Ocean (1780s), and as far away as the Japan grounds (1820) and the coast of Arabia (1820s), as well as Australia (1790s) and New Zealand (1790s).[80][81]

Hunting for sperm whales during this period was a notoriously dangerous affair for the crews of the 19th-century whaleboats. Although a properly harpooned sperm whale generally exhibited a fairly consistent pattern of attempting to flee underwater to the point of exhaustion (at which point it would surface and offer no further resistance), it was not uncommon for bull whales to become enraged and turn to attack pursuing whaleboats on the surface, particularly if it had already been wounded by repeated harpooning attempts. A commonly reported tactic was for the whale to invert itself and violently thrash the surface of the water with its fluke, flipping and crushing nearby boats.

The estimated historic worldwide sperm whale population numbered 1,100,000 before commercial sperm whaling began in the early 18th century.[82] By 1880, it had declined an estimated 29%.[82] From that date until 1946, the population appears to have recovered somewhat as whaling pressure lessened, but after the Second World War, with the industry's focus again on sperm whales, the population declined even further to only 33%.[82] In the 19th century, between 184,000 and 236,000 sperm whales were estimated to have been killed by the various whaling nations,[83] while in the modern era, at least 770,000 were taken, the majority between 1946 and 1980.[84] Remaining sperm whale populations are large enough so that the species' conservation status is vulnerable, rather than endangered.[82] However, the recovery from the whaling years is a slow process, particularly in the South Pacific, where the toll on males of breeding age was severe.[85]

Dolphins and porpoises are hunted in an activity known as dolphin drive hunting. This is accomplished by driving a pod together with boats and usually into a bay or onto a beach. Their escape is prevented by closing off the route to the ocean with other boats or nets. Dolphins are hunted this way in several places around the world, including the Solomon Islands, the Faroe Islands, Peru, and Japan, the most well-known practitioner of this method. By numbers, dolphins are mostly hunted for their meat, though some end up in dolphinariums.[86] Despite the controversial nature of the hunt resulting in international criticism, and the possible health risk that the often polluted meat causes,[87] thousands of dolphins are caught in drive hunts each year.[88]

In Japan, the hunting is done by a select group of fishermen.[89] When a pod of dolphins has been spotted, they are driven into a bay by the fishermen while banging on metal rods in the water to scare and confuse the dolphins. When the dolphins are in the bay, it is quickly closed off with nets so the dolphins cannot escape. The dolphins are usually not caught and killed immediately, but instead left to calm down over night. The following day, the dolphins are caught one by one and killed. The killing of the animals used to be done by slitting their throats, but the Japanese government banned this method, and now dolphins may officially only be killed by driving a metal pin into the neck of the dolphin, which causes them to die within seconds according to a memo from Senzo Uchida, the executive secretary of the Japan Cetacean Conference on Zoological Gardens and Aquariums.[90] A veterinary team's analysis of a 2011 video footage of Japanese hunters killing striped dolphins using this method suggested that, in one case, death took over four minutes.[91]

Since much of the criticism is the result of photos and videos taken during the hunt and slaughter, it is now common for the final capture and slaughter to take place on site inside a tent or under a plastic cover, out of sight from the public. The most circulated footage is probably that of the drive and subsequent capture and slaughter process taken in Futo, Japan, in October 1999, shot by the Japanese animal welfare organization Elsa Nature Conservancy.[92] Part of this footage was, amongst others, shown on CNN. In recent years, the video has also become widespread on the internet and was featured in the animal welfare documentary Earthlings, though the method of killing dolphins as shown in this video is now officially banned. In 2009, a critical documentary on the hunts in Japan titled The Cove was released and shown amongst others at the Sundance Film Festival.[93]

Toothed whales can also be threatened by humans more indirectly. They are unintentionally caught in fishing nets by commercial fisheries as bycatch and accidentally swallow fishing hooks. Gillnetting and Seine netting are significant causes of mortality in cetaceans and other marine mammals.[94] Porpoises are commonly entangled in fishing nets. Whales are also affected by marine pollution. High levels of organic chemicals accumulate in these animals since they are high in the food chain. They have large reserves of blubber, more so for toothed whales, as they are higher up the food chain than baleen whales. Lactating mothers can pass the toxins on to their young. These pollutants can cause gastrointestinal cancers and greater vulnerability to infectious diseases.[95] They can also be poisoned by swallowing litter, such as plastic bags.[96] Pollution of the Yangtze river has led to the extinction of the baiji.[97] Environmentalists speculate that advanced naval sonar endangers some whales. Some scientists suggest that sonar may trigger whale beachings, and they point to signs that such whales have experienced decompression sickness.[98][99][100][101]

Currently, no international convention gives universal coverage to all small whales, although the International Whaling Commission has attempted to extend its jurisdiction over them. ASCOBANS was negotiated to protect all small whales in the North and Baltic Seas and in the northeast Atlantic. ACCOBAMS protects all whales in the Mediterranean and Black Seas. The global UNEP Convention on Migratory Species currently covers seven toothed whale species or populations on its Appendix I, and 37 species or populations on Appendix II. All oceanic cetaceans are listed in CITES appendices, meaning international trade in them and products derived from them is very limited.[102][103]

Numerous organisation are dedicated to protecting certain species that do not fall under any international treaty, such as the Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita,[104] and the Wuhan Institute of Hydrobiology (for the Yangtze finless porpoise).[105]

Various species of toothed whales, mainly dolphins, are kept in captivity, as well as several other species of porpoise such as harbour porpoises and finless porpoises. These small cetaceans are more often than not kept in theme parks, such as SeaWorld, commonly known as a dolphinarium. Bottlenose dolphins are the most common species kept in dolphinariums, as they are relatively easy to train, have a long lifespan in captivity, and have a friendly appearance. Hundreds if not thousands of bottlenose dolphins live in captivity across the world, though exact numbers are hard to determine. Orca are well known for their performances in shows, but the number kept in captivity is very small, especially when compared to the number of bottlenose dolphins, with only 44 captives being held in aquaria as of 2012.[106] Other species kept in captivity are spotted dolphins, false killer whales, and common dolphins, Commerson's dolphins, as well as rough-toothed dolphins, but all in much lower numbers than the bottlenose dolphin. Also, fewer than ten pilot whales, Amazon river dolphins, Risso's dolphins, spinner dolphins, or tucuxi are in captivity. Two unusual and very rare hybrid dolphins, known as wolphins, are kept at the Sea Life Park in Hawaii, which is a cross between a bottlenose dolphin and a false killer whale. Also, two common/bottlenose hybrids reside in captivity: one at Discovery Cove and the other at SeaWorld San Diego.[107]

Organisations such as Animal Welfare Institute and the Whale and Dolphin Conservation campaign against the captivity of dolphins and orca.[108] SeaWorld faced a lot of criticism after the documentary Blackfish was released in 2013.[109]

Aggression among captive orca is common. In August 1989, a dominant female orca, Kandu V, attempted to rake a newcomer whale, Corky II, with her mouth during a live show, and smashed her head into a wall. Kandu V broke her jaw, which severed an artery, and then bled to death.[110] In November 2006, a dominant female killer whale, Kasatka, repeatedly dragged experienced trainer Ken Peters to the bottom of the stadium pool during a show after hearing her calf crying for her in the back pools.[111] In February 2010, an experienced female trainer at SeaWorld Orlando, Dawn Brancheau, was killed by orca Tilikum shortly after a show in Shamu Stadium.[112] Tilikum had been associated with the deaths of two people previously.[110][113] In May 2012, Occupational Safety and Health Administration administrative law judge Ken Welsch cited SeaWorld for two violations in the death of Dawn Brancheau and fined the company a total of US$12,000.[114] Trainers were banned from making close contact with the orca.[115] In April 2014, the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia denied an appeal by SeaWorld.[116]

In 2013, SeaWorld's treatment of orca in captivity was the basis of the movie Blackfish, which documents the history of Tilikum, an orca captured by SeaLand of the Pacific, later transported to SeaWorld Orlando, which has been involved in the deaths of three people.[117] In the aftermath of the release of the film, Martina McBride, 38 Special, REO Speedwagon, Cheap Trick, Heart, Trisha Yearwood, and Willie Nelson cancelled scheduled concerts at SeaWorld parks.[118] SeaWorld disputes the accuracy of the film, and in December 2013 released an ad countering the allegations and emphasizing its contributions to the study of cetaceans and their conservation.[119]

The toothed whales (also called odontocetes, systematic name Odontoceti) are a parvorder of cetaceans that includes dolphins, porpoises, and all other whales possessing teeth, such as the beaked whales and sperm whales. 73 species of toothed whales are described. They are one of two living groups of cetaceans, the other being the baleen whales (Mysticeti), which have baleen instead of teeth. The two groups are thought to have diverged around 34 million years ago (mya).

Toothed whales range in size from the 1.4 m (4.6 ft) and 54 kg (119 lb) vaquita to the 20 m (66 ft) and 55 t (61-short-ton) sperm whale. Several species of odontocetes exhibit sexual dimorphism, in that there are size or other morphological differences between females and males. They have streamlined bodies and two limbs that are modified into flippers. Some can travel at up to 20 knots. Odontocetes have conical teeth designed for catching fish or squid. They have well-developed hearing that is well adapted for both air and water, so much so that some can survive even if they are blind. Some species are well adapted for diving to great depths. Almost all have a layer of fat, or blubber, under the skin to keep warm in the cold water, with the exception of river dolphins.

Toothed whales consist of some of the most widespread mammals, but some, as with the vaquita, are restricted to certain areas. Odontocetes feed largely on fish and squid, but a few, like the orca, feed on mammals, such as pinnipeds. Males typically mate with multiple females every year, making them polygynous. Females mate every two to three years. Calves are typically born in the spring and summer, and females bear the responsibility for raising them, but more sociable species rely on the family group to care for calves. Many species, mainly dolphins, are highly sociable, with some pods reaching over a thousand individuals.

Once hunted for their products, cetaceans are now protected by international law. Some species are attributed with high levels of intelligence. At the 2012 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, support was reiterated for a cetacean bill of rights, listing cetaceans as nonhuman persons. Besides whaling and drive hunting, they also face threats from bycatch and marine pollution. The baiji, for example, is considered functionally extinct by the IUCN, with the last sighting in 2004, due to heavy pollution to the Yangtze River. Whales occasionally feature in literature and film, as in the great white sperm whale of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick. Small odontocetes, mainly dolphins, are kept in captivity and trained to perform tricks. Whale watching has become a form of tourism around the world.

La dentocetacoj (Odontoceti) formas subordon de cetacoj (Cetacea). Male al la bartocetacoj, ili havas dentojn en la makzeloj antataŭ bartoj. Ili manĝas karnon, ĉefe fiŝojn, sepiojn kaj malofte eĉ marajn mamulojn.

Plimulto de la dentocetacoj estas pli malgranda ol bartocetacoj. Oni listigas nur unu specion ĉe la grandaj cetacoj, nome la kaĉaloton. La ceteraj specioj estas malgrandaj aŭ mezgrandaj. Plua diferenco estas ke la dentocetacoj havas nur unu spirtruon (kaj ne du kiel la bartocetacoj). Ili havas nesimetrian kranion kaj cekumon.

La dentoj de la diversaj specioj estas diverse evoluintaj. Multaj havas eĉ ĝis 100 dentojn kiel ekzemple delfenedoj, male al ili narvalo havas nur unu longan puŝdenton. Ankaŭ ĉe la preskaŭ sendentaj bekocetedoj (Ziphiidae), la masklo havas bizare formitajn dentojn.

Plimulto de la dentocetacoj bone naĝas. Multaj delfenoj naĝas saltante.

La voĉesprimo estas tre grava por la dentocetacoj. Krom la multnombrajn aŭdeblajn fajfojn, ili uzas ankaŭ ultrasonajn voĉojn por la eĥolokiĝo. Tiu gravas ĉefe dum ĉasado.

Ili vivas plej ofte en grupoj ĝis ĉ. dekduopo.

La homo senkompate ĉasis ilin dum la pasintaj jarcentoj. Nun ili estas nur limigite ĉaseblaj, sed la medipoluado minacas ilin.

Oni dividas la dentocetacojn en 9 familiojn:

Detale:

La dentocetacoj (Odontoceti) formas subordon de cetacoj (Cetacea). Male al la bartocetacoj, ili havas dentojn en la makzeloj antataŭ bartoj. Ili manĝas karnon, ĉefe fiŝojn, sepiojn kaj malofte eĉ marajn mamulojn.

Los odontocetos (Odontoceti) son un parvorden de cetáceos. Se los conoce comúnmente como cetáceos dentados. Precisamente se caracterizan por la presencia de dientes en lugar de las barbas, como ocurre en los misticetos.

El nombre Odontoceti proviene del griego ὀδόντο- odonto, "diente" y κῆτος cetos, "gran animal marino".[1]

Los odontocetos son un parvorden de mamíferos cetáceos sin barbas, con un hocico provisto de dientes generalmente homodontes, que pueden ser numerosos o reducirse a un solo par, como es el caso de los zifios. Presentan un solo espiráculo (orificio respiratorio) en la parte superior de la cabeza y una frente abultada debido a la presencia del melón, órgano utilizado en la ecolocalización. Todos los odontocetos son carnívoros.[2][3]

Los odontocetos incluyen siete u ocho familias, según se considere el género Kogia como miembro de la familia Physeteridae[4] o integrante de una familia independiente[5] (Kogiidae).

No obstante, esta clasificación clásica no concuerda con la filogenia del grupo, pues la superfamilia Platanistoidea resulta ser un grupo parafilético. El cladograma basado en las relaciones filogenéticas[6] es el siguiente:

Los odontocetos (Odontoceti) son un parvorden de cetáceos. Se los conoce comúnmente como cetáceos dentados. Precisamente se caracterizan por la presencia de dientes en lugar de las barbas, como ocurre en los misticetos.

Hammasvaalalised (Odontoceti) on vaalaliste alamselts.

Hammasvaalalistel on teravad hambad, kuid ükski hammasvaalaline ei oska närida. Hambad on neil ainult saagi püüdmiseks.

Odontozeto (Odontoceti) ugaztunen klaseko zetazeoen ordenako itsasoko animalia batzuez esaten da. Odontozetoen ezaugarri berezia ahoa hortzez hornitua izatea da. Odontozeto-espezie batzuek bi barailetan dituzte hortzak, beste batzuek behekoan bakarrik. Gainerako zetazeoek baino aho estuagoa eta txikiagoa dute. Delfinidoak, monodontidoak eta platanistidoak dira odontozetoen azpiordenako familiarik ezagunenak. Odontozeto guztiak haragijaleak dira. Belugak, izurdeak, kaxaloteak, orkak, narbalak, mazopak eta pilotu-izurdeak odontozetoak dira.

Odontozeto zazpi edo zortzi familia osatzen dute, segun eta Kogia generoa Physeteridae familiaren barnean[1] edo familia independente bat osatzen[2] hartzen dugun.

Odontozeto (Odontoceti) ugaztunen klaseko zetazeoen ordenako itsasoko animalia batzuez esaten da. Odontozetoen ezaugarri berezia ahoa hortzez hornitua izatea da. Odontozeto-espezie batzuek bi barailetan dituzte hortzak, beste batzuek behekoan bakarrik. Gainerako zetazeoek baino aho estuagoa eta txikiagoa dute. Delfinidoak, monodontidoak eta platanistidoak dira odontozetoen azpiordenako familiarik ezagunenak. Odontozeto guztiak haragijaleak dira. Belugak, izurdeak, kaxaloteak, orkak, narbalak, mazopak eta pilotu-izurdeak odontozetoak dira.

Hammasvalaat (Odontoceti) on toinen valaiden nykyisistä alalahkoista. Siinä on hetulavalaiden lahkoa paljon enemmän lajeja. Hammasvalaiden ryhmään kuuluu pyöriäisiksi, delfiineiksi ja valaiksi kutsuttuja lajeja.

Hammasvalaat ovat keskimäärin hetulavalaita pienempiä. Pienimpien lajien pituus on noin metri, kookkain laji taas on 18 metrin pituinen kaskelotti. Koiras on aina naarasta suurempi. Hammasvalaiden saaliseläimet ovat paljon suurikokoisempia kuin hetulavalaiden.

Kallo on epäsymmetrinen valaiden kaikuluotauskyvyn takia: osa oikean puoliskon luista on kehittynyt voimakkaammiksi kuin vastaavat luut vasemmalla puolella.

Hampaiden lukumäärä vaihtelee kahdesta 250:een; joskus hampaita on vain alaleuassa. Hampaat ovat rakenteeltaan yksinkertaisia tarttumahampaita,[1] useimpien lajien hampaat ovatkin suipot ja terävät. Ravintonsa hammasvalaat nielevät silti kokonaisena, sillä hampaita ei käytetä saaliin hienontamiseen vaan vain sen kiinni saamiseen.

Sieraimet ovat kehittyneet yhdeksi epäsymmetrisesti sijaitsevaksi hengitysreiäksi,[2] joka sijaitsee päälaella. Hajulimakalvo ja aivojen hajukeskus puuttuvat kokonaan.

Kurkunpään kaksi rustoa muodostaa hanhen nokan muotoisen putken, joka ulottuu pitkälle nenäonteloon ja sulkeutuu tarvittaessa rengaslihaksen avulla. Hammasvalaiden suunnistuksessa ja viestinnässä käyttämä ääntely ei synny kurkunpäässä, koska äänijänteitä ei valailla ole lainkaan, vaan nenäontelossa.

Monien hammasvalaslajien aivot – etenkin pikkuaivot – ovat erittäin kehittyneet ja hyvin suuret. Aivokuori on paljon poimuisampi kuin ihmisellä[3].

Hammasvalaat (Odontoceti) on toinen valaiden nykyisistä alalahkoista. Siinä on hetulavalaiden lahkoa paljon enemmän lajeja. Hammasvalaiden ryhmään kuuluu pyöriäisiksi, delfiineiksi ja valaiksi kutsuttuja lajeja.

Hammasvalaat ovat keskimäärin hetulavalaita pienempiä. Pienimpien lajien pituus on noin metri, kookkain laji taas on 18 metrin pituinen kaskelotti. Koiras on aina naarasta suurempi. Hammasvalaiden saaliseläimet ovat paljon suurikokoisempia kuin hetulavalaiden.

Odontocètes

Les odontocètes (Odontoceti), ou cétacés à dents, constituent l'un des deux micro-ordres des cétacés. Ce groupe est caractérisé par la possession de dents (contrairement aux fanons des mysticètes, ou cétacés à fanons).

Le sous-ordre des odontocètes comprend les différentes espèces de bélugas, de cachalots, d'orques (ou épaulards), de dauphins, de marsouins, de narvals et de globicéphales.

Les odontocètes font partie des rares espèces animales (avec les chauves-souris, quelques oiseaux et certaines musaraignes) à posséder la capacité d'écholocalisation au moyen d'ultrasons. Ils s'en servent pour repérer leurs proies et s'orientent en analysant les échos des sons qu'ils émettent : une fonction qui s'apparente au système du sonar.

Les odontocètes sont, en général, plus petits que les mysticètes.

L'odorat serait un sens très peu utilisé chez les baleines à dents, qui n'ont pas de muqueuse olfactive, ni de nerf olfactif. Cependant, ces animaux ont toujours l'organe voméro-nasal, impliqué dans la détection de phéromones[1].

Les odontocètes sont homodontes c'est-à-dire que leurs dents, sauf exception comme le narval qui en principe ne possède qu'une défense, sont identiques entre elles. La dentition est très différente parmi ces espèces, le clade formé par les Ziphiidae et les Monodontidae n'en possédant que deux, tandis que certains espèces de Platanistidae en ont plus de 130[2]. Les dents de lait des odontocètes ne tombent pas, la seconde série reste atrophiée. Les dents des odontocètes servent à agripper les proies et leur forme dépend de leur régime alimentaire. Ainsi, leur nombre et leur forme permettent aux spécialistes d'en déduire l'espèce. Certaines espèces telles que les baleines à becs ou encore les cachalots ne possèdent de dents que sur la mâchoire inférieure.

Comme tous les mammifères, les odontocètes possèdent des poumons et doivent périodiquement respirer à la surface. Les odontocètes n'ont qu'un seul évent, ce qui les distingue des mysticètes, ou baleines à fanons, qui en ont deux.

Les Odontocètes présentent un crâne asymétrique, ce qui n'est pas le cas chez les Mysticètes. Plusieurs chercheurs relient cette déformation à l'écholocation[3] leur permettant la production de sons de hautes fréquences. Cependant, bien que certains scientifiques aient déjà émis cette hypothèse[4], des études récentes (2011)[5] tendent à démontrer que les Archéocètes, dont descendent les Cétacés, présentaient déjà un crâne asymétrique malgré le fait qu'ils n'utilisaient pas l'écholocation. Ces chercheurs associent donc l'asymétrie du crâne à une meilleure ouïe pour entendre les bruits émis par leurs proies, et non pas l'écho d'un son émis par le prédateur. Les Mysticètes auraient, au fil du temps, retrouvé un crâne symétrique. Des recherches plus poussées seront nécessaires pour clore la question.

Beaucoup d'espèces sont sociales. Elles forment des groupes d'individus avec une structure sociale complexe, collaborant pour la chasse et la défense mutuelle.

De nombreuses expériences en éthologie cognitive ont démontré leur grande intelligence.

Ils savent se reconnaître lorsqu'on les place devant un miroir dans le cadre du test du miroir de Gallup. À l'heure actuelle, à part les dauphins, cette capacité n'a été observée que chez les humains, certains singes et les éléphants. Ceci suggère que ces animaux ont conscience d'eux-mêmes.

On a aussi récemment observé des dauphins faire usage d'outils, fait rarement observé dans le règne animal. Ainsi, des dauphins ont été observés en train d'utiliser des éponges de mer pour se protéger le museau lorsqu'ils raclent le fond marin[6]. Depuis, il a été démontré que cette technique était transmise par apprentissage des mères aux filles[7].

Les delphinés sont une des rares espèces qui pratiquent le sexe aussi pour le plaisir, sans intention de procréation[réf. nécessaire].

On considère qu'ils représentent un cas de convergence évolutive avec les primates et en particulier, les hominidés, pour leurs grandes capacités cognitives en comparaison avec les autres taxons de mammifères marins.

Leur langage fondé sur des sifflements bruyants et des ultra-sons inaudibles pour l'oreille humaine semble être très élaboré mais est encore mal compris. Les études menées avec des grands dauphins ont démontré qu'ils étaient capables d'identifier la "voix" des différents individus de leur groupe[8].

Bien que presque unanimement appréciés par l'Homme, les odontocètes sont exposés à des menaces croissantes :

Les odontocètes de Méditerranée sont atteints par une épidémie[10], dont la cause a été identifiée comme une atteinte virale par Morbillivirus[11]. Cette épidémie atteint plus les jeunes. Or, ces mammifères sont presque exclusivement des consommateurs de poissons et sont ainsi, vu la contamination élevée de leur alimentation, atteints par des intoxications liées en particulier au PCB (polychlorobiphényle)[12] ; ce toxique, stocké dans les graisses et transmis par le lait, induit une atteinte des moyens normaux de défense du jeune animal, ce qui favoriserait en conséquence l'atteinte virale.

Faute de données, l'UICN n'arrive pas à établir de diagnostic clair des menaces liées à la pêche commerciale. L'UNESCO présume que, chaque année, environ 100 000 odontocètes seraient abattus à des fins commerciales, et 300 000 autres mourraient étouffés dans des filets abandonnés. La pêche industrielle aux thons, florissante dans le Pacifique Est, s'avère être une calamité pour ces cétacés. En 1990, le Congrès des États-Unis a donc créé le label « Dolphin Safe », pour signaler aux consommateurs les pratiques les plus vertueuses[13]. Autre fléau : la malnutrition, qui guette l'animal depuis que ses proies habituelles (harengs, sardines, maquereaux…) sont pêchées de manière intensive.

Le sous-ordre contient 6 familles :

Plus 4 familles au statut discuté :

Squelette de Xiphiacetus (espèce fossile)

Odontocètes

Les odontocètes (Odontoceti), ou cétacés à dents, constituent l'un des deux micro-ordres des cétacés. Ce groupe est caractérisé par la possession de dents (contrairement aux fanons des mysticètes, ou cétacés à fanons).

Le sous-ordre des odontocètes comprend les différentes espèces de bélugas, de cachalots, d'orques (ou épaulards), de dauphins, de marsouins, de narvals et de globicéphales.

Les odontocètes font partie des rares espèces animales (avec les chauves-souris, quelques oiseaux et certaines musaraignes) à posséder la capacité d'écholocalisation au moyen d'ultrasons. Ils s'en servent pour repérer leurs proies et s'orientent en analysant les échos des sons qu'ils émettent : une fonction qui s'apparente au système du sonar.

Os odontocetos (Odontoceti, Flower, 1867) constitúen unha suborde dos cetáceos caracterizados por posuíren dentes, a diferenza das baleas e especies similares (misticetos) que posúen unhas formacións quitinosas chamadas barbas, con función filtradora.

O nome Odontoceti provén do grego antigo ὀδόντο- odónto-, "dente" e κῆτος kêtos, "gran monstro mariño".[1]

A característica definitoria do taxon é a presenza de dentes, polo que as especies de gran tamaño, reciben o nome (impropio) de baleas dentadas ou baleas con dentes. Os dentes son cónicos, ocos e indiferenciados (homodontes) e poden presentarse en número moi variable, desde os 160-240 do golfiño común ata o dente único do narval.[2] Así mesmo varía a súa disposición, presente nas dúas mandíbulas ou só na inferior (como nos cachalotes ou algúns zifios) ou na superior (narval), e o seu tamaño, que oscila entre uns milímetros na toniña e os dous metros no narval.

Os dentes non teñen función mastigatoria senón que serven para capturar as presas, que engolen enteiras. Aínda así, non sempre cumpren esa función e nalgunhas especies convértense en caracteres de diferenciación sexual, como acontece tipicamente no narval.

Presentan un único espiráculo (orificio respiratorio) na parte superior da cabeza e unha fronte avultada debida ás modificacións anatómicas producidas pola presenza do melón, denominación popular do órgano da ecolocación.

Todos os odontocetos son carnívoros.

Os odontocetos clasifícanse dentro da orde Cetacea e distribúense en dez familias (algunhas delas discutidas):

Modernamente moitos autores agrupan estas familias en seis superfamilias:[3]

Dentadura do golfiño común

Candorcas saltando no aire

Cranio de candorca

Maxilar inferior do cachalote

Os odontocetos (Odontoceti, Flower, 1867) constitúen unha suborde dos cetáceos caracterizados por posuíren dentes, a diferenza das baleas e especies similares (misticetos) que posúen unhas formacións quitinosas chamadas barbas, con función filtradora.

Kitovi zubani (lat. Odontoceti) su jedan od dva podreda kitova (Cetacea). Suprotno od kitova usana oni imaju zube u čeljustima. Oni su svi mesožderi koji se hrane pretežno ribama i glavonošcima, a u nekim slučajevima love i morske sisavce.

Većina kitova zubana su puno manji od kitova usana. Samo jedna porodica iz ove grupe, ulješura se ubraja u velike kitove. Osim veličinom, od kitova usana se razlikuju i po tome, što imaju samo jedan nosni otvor a ne dva, kao usani.

Različite vrste ovih kitova imaju i sasvim različito izražene zube. Mnogi zubani imaju veliki broj zubi, sve do stotinjak kod nekih vrsta dupina, dok narval ima jedan vrlo dugačak zub, kao kljovu. I mužjaci gotovo bezubih kljunastih kitova imaju bizarno oblikovane zube.

Većina kitova zubana su vrlo brzi plivači. Neke male vrste ponekad jašu na valovima, recimo, na valovima koje za sobom ostavljaju brodovi. Posebno često se tako viđa dupine, koji su uz to poznati i po svojim akrobatskim skokovima.

Kod zubana glasanje ima vrlo važnu ulogu. Pored brojnih zviždukavih glasova pomoću kojih međusobno komuniciraju, oni se koriste i ultrazvukom za eholociranje, poput radara. Ovo im je osjetilo izuzetno važno u lovu.

Kitovi zubani žive u grupama od nekoliko pa do petnaestak jedinki. Ove tzv. "škole" se mogu povremeno okupiti u grupe velike i do tisuću jedinki. Ovi su kitovi sposobni za vrlo kompleksno ponašanje kao što je, recimo, međusobna suradnja u lovu na jata riba. U zatočeništvu, neke vrste pokazuju iznimno veliku sposobnost učenja, zbog čega ih zoolozi svrstavaju među najinteligentnije životinje uopće.

Kitove zubane se dijeli na devet porodica:

Postoje mnoge naznake, da se neke od ovih porodica svrstaju u nadporodice. No, prilično sigurno je samo, da su porodice oceanskih dupina, pliskavica i bijelih kitova međusobno srodne. Njih se ponekad obuhvaća zajedno u grupu Delphinidae. Suprotno tome, pokušaji da se Indijski, Kineski (koji se često naziva još i Baiji), La Plata, i Boto (koji se često naziva još i amazonskim dupinom) dupini svrstaju zajedno u grupu riječnih dupina nisu održivi. Ovim vrstama je zajedničko samo to što žive u slatkim vodotocima, no sasvim sigurno su se razvili neovisno jedni od drugih. Ulješure i kljunasti kitovi su vjerojatno prvobitne porodice kitova zubana, i nemaju bližih srodničkih veza s nijednom drugom porodicom.

Ulješure su dugo bile izlovljavane za potrebe industrije. Dok se neke manje vrste još uvijek izlovljavaju, većina vrsta su ugrožene prije svega jalovim ulovom. Kod lova na tune se u mrežama utapaju tisuće oceanskih dupina, postajući tako jalovi ulov. Ne koristi nikom, a silno šteti vrstama koje pri tome stradavaju.

Wikivrste imaju podatke o: OdontocetiKitovi zubani (lat. Odontoceti) su jedan od dva podreda kitova (Cetacea). Suprotno od kitova usana oni imaju zube u čeljustima. Oni su svi mesožderi koji se hrane pretežno ribama i glavonošcima, a u nekim slučajevima love i morske sisavce.

Paus bergigi (nama sistematis Odontoceti) merupakan infraordo dari subordo artiodactyla Cetacea, termasuk paus sperma, paus berparuh, lumba-lumba, dan lain-lain. Setidaknya satu penulis percaya bahwa Cetacea harus terbaik diakui sebagai infraordo dalam subordo Whippomorpha di Artiodactyla.[1] Seperti namanya, subordo ini ditandai dengan adanya gigi daripada balin paus lainnya.

Paus bergigi (nama sistematis Odontoceti) merupakan infraordo dari subordo artiodactyla Cetacea, termasuk paus sperma, paus berparuh, lumba-lumba, dan lain-lain. Setidaknya satu penulis percaya bahwa Cetacea harus terbaik diakui sebagai infraordo dalam subordo Whippomorpha di Artiodactyla. Seperti namanya, subordo ini ditandai dengan adanya gigi daripada balin paus lainnya.