en

names in breadcrumbs

A small (7-10 inches) owl, the Eastern Screech-Owl is most easily identified by its size, streaked breast, and ear-like feather tufts. This species has two color morphs, one with gray plumage and the other with rusty-red plumage. Male and female Eastern Screech-Owls are similar to one another in all seasons. The Eastern Screech Owl inhabits much of the eastern United States and southern Canada west to the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains. This species also occurs in northern Mexico south to the Tropic of Cancer. Eastern Screech-Owls are non-migratory in all parts of their range. Eastern Screech-Owls inhabit a variety of deciduous, evergreen, or mixed woodland habitats. This species may also be found in more built-up areas, and can sometimes be found in large urban parks. Eastern Screech-Owls eat a variety of small animals, such as insects, songbirds, and rodents. Like most owls, the Eastern Screech-Owl hunts almost exclusively at night, making it difficult to observe. This owl may be more visible when it is active at dusk or just before sunrise, and birds roosting in trees may be seen during the day with the aid of binoculars. As its name suggests, the Eastern Screech-Owl produces a high-pitched hooting call which may be used to identify this species at night.

A small (7-10 inches) owl, the Eastern Screech-Owl is most easily identified by its size, streaked breast, and ear-like feather tufts. This species has two color morphs, one with gray plumage and the other with rusty-red plumage. Male and female Eastern Screech-Owls are similar to one another in all seasons. The Eastern Screech Owl inhabits much of the eastern United States and southern Canada west to the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains. This species also occurs in northern Mexico south to the Tropic of Cancer. Eastern Screech-Owls are non-migratory in all parts of their range. Eastern Screech-Owls inhabit a variety of deciduous, evergreen, or mixed woodland habitats. This species may also be found in more built-up areas, and can sometimes be found in large urban parks. Eastern Screech-Owls eat a variety of small animals, such as insects, songbirds, and rodents. Like most owls, the Eastern Screech-Owl hunts almost exclusively at night, making it difficult to observe. This owl may be more visible when it is active at dusk or just before sunrise, and birds roosting in trees may be seen during the day with the aid of binoculars. As its name suggests, the Eastern Screech-Owl produces a high-pitched hooting call which may be used to identify this species at night.

The eastern screech owl (Megascops asio) or eastern screech-owl, is a small owl that is relatively common in Eastern North America, from Mexico to Canada.[1][3] This species is native to most wooded environments of its distribution, and more so than any other owl in its range, has adapted well to manmade development, although it frequently avoids detection due to its strictly nocturnal habits.[4]

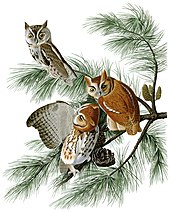

Adults range from 16 to 25 cm (6+1⁄2 to 10 in) in length and weigh 121–244 g (4+1⁄4–8+5⁄8 oz).[5] Among the differently sized races, length can average from 19.5 to 23.8 cm (7+11⁄16 to 9+3⁄8 in). The wingspan can range from 46 to 61 cm (18 to 24 in). In Ohio, male owls average 166 g (5+7⁄8 oz) and females 194 g (6+7⁄8 oz) while in central Texas, they average 157 g (5+1⁄2 oz) and 185 g (6+1⁄2 oz), respectively.[6][7] They have either rusty or dark gray intricately patterned plumage with streaking on the underparts. Midsized by screech-owl standards, these birds are stocky, short-tailed (tail averages from 6.6 to 8.6 cm (2+5⁄8 to 3+3⁄8 in) in length) and broad-winged (wing chord averages from 14.5 to 17 cm (5+3⁄4 to 6+3⁄4 in) in length) as is typical of the genus. They have a large, round head with prominent ear tufts, yellow eyes, and a yellowish beak, which measures on average 1.45 cm (9⁄16 in) in length. The feet are relatively large and powerful compared to more southern screech owls and are typically feathered down to the toes, although the southernmost populations only have remnant bristles rather than full feathering on the legs and feet. The eastern screech owl (and its western counterpart) are actually some of the heaviest screech owls, the largest tropical screech owls do not exceed them in average or maximal weight, but (due to the eastern screech owls' relatively short tails) they are surpassed in length by Balsas (M. seductus), long-tufted (M. sanctaecatarinae), white-throated (M. albogularis), and rufescent owls (M. seductus), in roughly increasing order.[8][9]

Two color variations are referred to as "red or rufous morphs" and "gray morphs" by bird watchers and ornithologists. Rusty birds are more common in the southern parts of the range; pairings of the two color variants do occur. While the gray morph provides remarkably effective camouflage amongst the bark of hardwood trees, red morphs may find security in certain pine trees and the colorful leaves of changing deciduous trees. The highest percentage of red morphs is known from Tennessee (79% of population) and Illinois (78% of population). A rarer "brown morph" is known, recorded exclusively in the south (i.e. Florida), which may be the occasional product of hybridation between the morphs. In Florida, brown morphs are typically reported in the more humid portions of the state, whereas they appear to be generally absent in the northern and northwestern parts of the state. A paler gray variation (sometimes bordering on a washed-out, whitish look) also exists in western Canada and the north-central United States.[10]

In the closely related western screech owl (Megascops kennicottii), no color morphs are known; all owls of the western species are gray. Besides coloration, the western screech owl is of almost exactly the same general appearance and size as the eastern. The only reliable distinguishing feature is the bill color, which is considerably darker (often a black-gray) in the western and olive-yellow in the eastern; their voices also differ. The eastern and western screech owls overlap in the range in the Rio Grande valley at the Texas–Mexico border and the riparian woods of the Cimarron tributary of the Arkansas River on the edge of southern Great Plains.[4] Other somewhat similar species that may abut the eastern screech owl's range in its western and southernmost distribution, like the Middle American screech owl (Megascops guatemalae; formerly called "vermiculated screech owl"), whiskered screech owl (Megascops trichopsis), and the flammulated owl (Psiloscops flammeolus), are distinguished by their increasingly smaller body and foot size, different streaking pattern on breast (bolder on the whiskered, weaker on the others), different bare part coloration, and distinctive voices. Through much of the eastern United States, eastern screech owls are essentially physically unmistakable, because other owls with ear tufts are much larger and differently colored and the only other small owl, the northern saw-whet owl (Aegolius acadius) is even smaller, with no ear tufts, a more defined facial disc, and browner overall color.[10]

Five subspecies are typically treated for the eastern screech owl, but the taxonomy in the species is considered "muddled". Much of the variation may be considered clinal, as predictably, the size tends to decrease from north to south and much of the color variation is explainable by adaptation to habitat.

Eastern screech owls exhibit a similar polymorphism as tawny owls, where plumage ranges from rufous to gray. The inheritance of morph in owls is likely complex, but rufous plumage may be controlled by a dominant allele and gray plumage alleles are recessive. There are latitudinal clines in screech owl polymorphism, with northern latitudes containing mostly gray individuals and southern latitudes containing primarily rufous individuals. This cline may be driven by higher metabolic rates in rufous individuals compared to gray individuals.[15] Evidence of higher metabolic rates was show by a higher proportion of gray morphs in the rural areas surrounding Waco, TX compared to the warmer suburban areas.[16] Rufous screech owls also had higher mortality during cold winters.[15]

Eastern screech owls inhabit open mixed woodlands, deciduous forests, parklands, wooded suburban areas, riparian woods along streams and wetlands (especially in drier areas), mature orchards, and woodlands near marshes, meadows, and fields. They try to avoid areas known to have regular activity of larger owls, especially great horned owls (Bubo virginianus). Their ability to live in heavily developed areas outranks even the great horned and certainly the barred owl (Strix varia); screech owls also are considerably more successful in the face of urbanization than barn owls (Tyto alba) following the conversion of what was once farmland.[4] Due to the introduction of open woodland and cultivated strips in the Great Plains, the range of eastern screech owls there has expanded.[4] Eastern screech owls have been reported living and nesting in spots such as along the border of a busy highway and on the top of a street light in the middle of a busy town square. They often nest in trees in neighborhoods and urban yards inhabited by humans. In such urban environments, they often meet their dietary needs via introduced species that live close to humans such as house sparrows (Passer domesticus) and house mice (Mus musculus).[4] They also consume anole lizards and large insects such as cicadas. They occupy the greatest range of habitats of any owl east of the Rockies. Eastern screech owls roost mainly in natural cavities in large trees, including cavities open to the sky during dry weather. In suburban and rural areas, they may roost in manmade locations such as behind loose boards on buildings, in boxcars, or on water tanks. They also roost in dense foliage of trees, usually on a branch next to the trunk, or in dense, scrubby brush. The distribution of the species is largely concurrent with the distribution of eastern deciduous woodlands, probably discontinuing at the Rocky Mountains in the west and in northern Mexico in the south due to the occupation of similar niches by other screech owls and discontinuing at the start of true boreal forest because of the occupation of a similar niche by other small owls (especially boreal owls (Aegolius funereus). Eastern screech owls may be found from sea level up to 1,400 m (4,600 ft) in elevation in the eastern Rocky Mountains and up to 1,500 m (4,900 ft) in the eastern Sierra Madre Oriental Mountains, although their altitudinal limits in the Appalachian Mountains, near the heart of their distribution, is not currently known.[4][8]

Eastern screech owls are strictly nocturnal, roosting during the day in cavities or next to tree trunks. They are quite common, and can often be found in residential areas. However, due to their small size and camouflage, they are much more frequently heard than actually seen. These owls are frequently heard calling at night, especially during their spring breeding season. Despite their name, this owl does not truly screech. The eastern screech owl's call is a tremolo with a descending, whinny-like quality, like that of a miniature horse. They also produce a monotone purring trill lasting 3–5 seconds. Their voices are unmistakable and follow a noticeably different phrasing than that of the western screech owl. The lugubrious nature of the eastern screech owl's call has warranted description such as, "A most solemn graveyard ditty, the mutual consolation of suicide lovers remembering the pangs and delights of the supernal love in the infernal groves, Oh-o-o-o-o that I never had been bor-r-r-r-n!.[17]

Their breeding habitat is deciduous or mixed woods in eastern North America. Usually solitary, they nest in a tree cavity, either natural or excavated by a woodpecker. Holes must have a 7 to 20 cm (3 to 8 in) entrance to accommodate this owl. Usually, they fit only in the holes excavated by northern flickers (Colaptes auratus) or pileated woodpeckers (Dryocopus pileatus), as apparently the midsized red-bellied woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinensis) make holes that are not large enough to accommodate them.[18] Orchards, which often have trees with crevices and holes, as well as meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus), a dietary favorite, are often preferred nesting habitats.[4] Eastern screech owls also use nesting boxes erected by humans. Although some people put up nest boxes meant for screech owls, the owls also take over nest boxes meant for others, such as those for wood ducks (Aix sponsa), houses erected for purple martins (Progne subis), and dovecotes put up for rock pigeons (Columba livia), occasionally killing and consuming at least the latter two in the process of taking over the nest box. A 9-year study comparing the breeding success of eastern screech owls nesting in natural cavities and nesting in nest boxes showed that the fledging rate was essentially the same, although in some years, up to 10% more success occurred in the natural cavities.[18] Depending on the origins of the hole being used, eastern screech owl nests have been recorded from 1.5 to 25 m (5 to 80 ft) off the ground.[4] Like all owls, these birds do not actually build a nest; instead, females lay their eggs directly on the bare floor of the nest hole or on the layer of fur and feathers left over from previous meals that line the bottom of its den. Breeding pairs often return to the same nest year after year.[19]

This species commences egg laying on average about two months after great horned owls, but about two weeks before American kestrels (Falco sparveius) and almost throughout the range lays its first egg at some point in April.[4] Eggs are laid at two-day intervals and incubation begins after laying of the first egg. Eggs vary in size in synch with their ultimate body size, ranging from an average of 36.3 mm × 30.2 mm (1+7⁄16 in × 1+3⁄16 in) in the Northern Rockies to 33.9 mm × 29.2 mm (1+5⁄16 in × 1+1⁄8 in) in south Texas.[4] From one to six eggs have been recorded per clutch, with an average of 4.4 in Ohio, 3.0 in Florida, and 4.56 in the north-central United States.[20] The incubation period is about 26 days, and the young reach the fledging stage at about 31 days old. Females do most of the incubating and brooding, but males also occasionally take shifts. As is the typical division of labor in owls, the male provides most of the food while the female primarily broods the young, and they stockpile food during the early stages of nesting, although the male tends to work hard nightly because many nestlings often appear to live almost entirely on freshly caught insects and invertebrates. The male's smaller size make it superior in its nimbleness, which allows it to catch insects and other swift prey.[4][8] Eastern screech owls are single-brooded, but may renest if the first clutch is lost, especially towards the southern end of its range. When the young are small, the female tears the food apart for them. The female, with her larger size and harder strike, takes on the duty of defending the nest from potential threats, and even humans may be aggressively attacked, sometimes resulting in them drawing blood from the head and shoulders of human passers-by.[4]

Like most predators, eastern screech owls are opportunistic hunters. Due to the ferocity and versatility of their hunting style, early authors nicknamed eastern screech owls "feathered wildcats".[21] In terms of ecological niche, they have no easy ecological equivalent in Europe, perhaps the closest being the little owl (Athene noctua), the similar looking Eurasian scops owl (Otus scops) being smaller and weaker and the long-eared owl (Asio otus) more fully dependent on rodents. The success of eastern screech (and western screech) owls in North America may be the reason long-eared owls are much more restricted to limited northern forest habitat in North America than they are in Europe.[4] Eastern screech owls hunt from dusk to dawn, with most hunting being done during the first four hours of darkness. A combination of sharp hearing and vision is used for prey location. These owls hunt mainly from perches, dropping down onto prey. Occasionally, they also hunt by scanning through the treetops in brief flights or hover to catch prey. This owl mainly hunts in open woodlands, along the edges of open fields or wetlands, or makes short forays into open fields. When prey is spotted, the owl dives quickly and seizes it in its talons. Small prey usually is swallowed whole on the spot, while larger prey is carried in the bill to a perch and then torn into pieces. An eastern screech owl tends to frequent areas in its home range where it hunted successfully on previous nights. The eastern screech owl's sense of hearing is so acute, it can even locate mammals under heavy vegetation or snow. The bird's ears (as opposed to its ear tufts) are placed asymmetrically on its head, enabling it to use the differences between each ear's perception of sound to home in on prey. Additionally, the feathers the eastern screech owl uses to fly are serrated at their tips. This muffles the noise the bird makes when it flaps its wings, enabling it to sneak up on prey quietly. Both the specialized ear placement and wing feathers are a feature shared by most living owl species to aid them in hunting in darkness.[19]

During the breeding season, large insects are favored in their diet, with invertebrates often composing more than half of the owls' diet. Some regularly eaten insects include beetles, moths, crickets, grasshoppers, katydids,[22] and cicadas, although they likely consume any commonly available flying insect. Also taken are crayfish, snails, spiders, earthworms, scorpions, leeches, millipedes, and centipedes. Small mammals, ranging in size from shrews to young rabbits (Sylvilagus ssp.), are regular prey and almost always become the owl's primary food during winter. Small rodents such as microtine rodents and mice account for about 67% of mammals taken, although rodents of a similar weight to the owl, such as rats and squirrels, especially the red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus), are also taken. Jumping mice (Zapus ssp.), chipmunks, moles, and bats (especially the little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) may be taken occasionally. Small birds such as chickadees (Poecile ssp.), swallows, sparrows, finches, flycatchers,[23] and warblers are the most common avian prey, and such species are normally caught directly from their nocturnal perches or during nocturnal migration. In Ohio, the most commonly reported avian prey species, and most commonly stored food items behind meadow voles, were yellow-rumped warblers (Setophaga coronata) and white-throated sparrows (Zonotrichus albicollis).[20] Abundant midsized avian or largish passerine prey are also not uncommon foods, such as mourning doves (Zenaida macroura), downy woodpeckers (Picoides pubescens), northern flickers, blue jays (Cyanocitta cristata), American robins (Turdus migratorius), European starling (Sturnus vulgaris), red-winged blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus), and common grackles (Quiscalus quiscula). However, larger avian prey are sometimes caught, including northern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus) and American woodcocks (Scolopax minor) and even rock pigeons and ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus), most likely young or fledgling aged birds, but all of which are likely to be heavier than the screech owls themselves. All told, more than 100 species of bird have been hunted by eastern screech owls. Irregularly, small fish, small snakes (i.e. Heterodon ssp.), lizards, baby soft-shelled turtles (Apalone ssp.), small frogs such as tree frogs and northern leopard frogs (Lithobates pipiens), toads, newts, and salamanders are also preyed upon. They have even been observed hunting for fish at fishing holes made by people or cracks in ice at bodies of water during winter. The most commonly reported fish prey in Ohio were American gizzard shad (Dorosoma cepedianum) and green sunfish (Lepomis cyanellus).[20][24] Brown bullheads (Ameiurus nebulosus) have been captured by eastern screech owls along coastal areas during winter.[4]

From hundreds of prey remains from Ohio, 41% were found to be mammals (23% of which were mice or voles), 18% were birds, and 41% were insects and other assorted invertebrates. Of vertebrates taken in the nesting season, 65% were birds (of about 54 species), 30% were mammals (11% meadow voles; 8% each of house mice and deermice of the genus Peromyscus), 3% were fish, and less than 2% were reptiles and amphibians.[20] In Michigan, among winter foods, 45–50% were meadow voles, 45% were white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus) and 1–10% were birds; during the summer, these respective numbers changed to 30, 23, and 19%, with as much as 28% of the food in summer being crayfish (Cambarus ssp.).[25] Due to meeting the needs of their nestlings, eastern screech owls frequently consume less per day during summer than they do during winter. Five owls captured in April, averaging about 160 g (5+3⁄4 oz) in males and 190 g (6+3⁄4 oz) in females, gained on average 28 g (1 oz) when captured in fall (October–December) and 13 g (1⁄2 oz) when captured in winter (January–February).[20] In Michigan, screech owls consumed about 25% of their own weight per day during winter against 16% of their weight in summer. The average weight of vertebrate prey for screech owls in Michigan is 26 g (15⁄16 oz)[25] In Wisconsin, the average weight of vertebrate prey is 28 g (1 oz).[26] While much of their insect prey can weigh only a fraction of a gram, their largest prey, such as adult rats and pigeons and juvenile rabbits and gamebirds, can weigh up to at least 350 g (12+1⁄4 oz).[4]

Eastern screech owls are known for their ability to live in close proximity to humans. There is previous information pointing to potential behavioral adaptations of urban and suburban eastern screech owls from their rural counterparts. There have been previous studies that found suburban eastern screech owls breed no differently in man-made nest boxes than in natural tree cavities.[27] Climate, food sources, and predator presence are some potential factors that impact the behaviors of suburban and rural eastern screech owls.[28] Living in suburbia can have some additional impacts on eastern screech owl behavior such as secondary poisoning, vehicles, and more predation and competition from raccoon, opossum and squirrels.[28]

Previous research has shown that male eastern screech owls find and defend two to three potential nesting sites (man-made and natural) in order to have backups for failed first nesting attempts. However, in a study by Gehlbach[27] it was found that suburban eastern screech owls had fewer alternative nesting sites due to humans cutting down trees with natural cavities, pruning the trees, or filling in the natural cavities with cement. Gehlbach[27] also found that nesting sites close to houses and with fewer surrounding shrubs were some of the most used. Additionally, older eastern screech owls were found to be more likely to habituate to human disturbances compared to younger eastern screech owls. A study by Artuso[29] found that there were larger average brood sizes and earlier average fledging dates of eastern screech owls shown in moderate and high-density suburban areas than in low-density suburban and rural areas.[29] Urban and suburban populations of eastern screech owls are more dense and productive than their rural counterparts.[30] There are various differences in habitat that have impacts on the nesting behaviors of eastern screech owls.

Eastern screech owl feeding behaviors have also been shown through previous research to be impacted by whether the owl lived in a rural or suburban area. In a previous study, prey diversity for eastern screech owls peaked in low-density suburban areas.[29] The owl's feeding habits changed based on the habitat type—owls in low-density suburban sites consumed almost double the amount of birds in non-breeding season as owls in high-density sites and triple that of owls in rural sites. Rural owls generally consumed more invertebrates and fewer caterpillars and earthworms.[29] It is already known that eastern screech owl diets vary throughout the breeding and non-breeding season, but now there is more research describing habitat's role in feeding behaviors as well.

The climate within urban or suburban and rural areas differ as well which in turn impacts eastern screech owl behavior. Suburban climate is typically warmer than rural climate due to the "heat island effect".[31] A previous study showed that as suburban climates got warmer over the course of a few years, eastern screech owls started nesting an average of 4.5 days earlier annually.[30] There were also more avian prey and a 93% success rate in annual nests. Bird baths and feeders located in the suburban habitats were also noted as being likely factors in enhancing residence successes.[30]

While eastern screech owls have lived for over 20 years in captivity, wild birds seldom, if ever, live that long. Mortality rates of young and nestling owls may be as high as 70% (usually significantly less in adult screech owls). Many losses are due to predation. Common predators at screech owl nests including Virginia opossums (Didelphis virginiana), American minks (Neogale vison), weasels (Mustela and Neogale sp.), raccoons (Procyon lotor), ringtails (Bassariscus astutus), skunks (Mephitis and Spilogale sp.), snakes, crows (Corvus sp.), and blue jays (Cyanocitta cristata).[4][10][32] Eastern fox squirrels (Sciurus niger) may raid the tree holes being used by eastern screech owls, not only destroying or consuming the eggs, but also displacing the adult owls from the hole to use the hole for themselves.[25] Adults have fewer predators, but larger species of owls do take them, since they have similar periods of activity. Larger owls known to have preyed on eastern screech owls have included great horned owls (Bubo virginianus), barred owls (Strix varia), spotted owls (Strix occidentalis), long-eared owls (Asio otus), short-eared owls (Asio flammeus), and snowy owls (Bubo scandianus). Diurnal birds of prey may also kill and eat them, including Cooper's hawks (Accipiter cooperii), northern harriers (Circus cyaenus), red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis), red-shouldered hawk (Buteo lineatus) and rough-legged hawks (Buteo lagopus).[4][21] Most prolific by far of the eastern screech owl's avian predators is the great horned owl, which can destroy up to 78% of a local population, but locally, Cooper's hawks and barred owls are almost as serious of a threat.[25][33] A most dramatic case illustrating the owl food chain involved a barred owl, which upon examination after being shot in New England, contained a long-eared owl in its stomach that, in its own stomach, contained an eastern screech owl.[21] All other common owls in this species range also live on similar rodent prey, but direct competition is obviously disadvantageous to the screech owl. One exception is the even smaller northern saw-whet owl, on which eastern screech owls have been known to prey.[4] In rural Michigan, 9 different species of owls and diurnal raptors including the screech owl fed primarily on the same four species of small rodents from the Peromyscus and Microtus genera.[25] Eastern screech owls have had nesting attempts fail due to biocide poisoning, which causes the thinning of eggs and failure of nests, but seemingly not to the overall detriment of the species. Collisions with cars, trains, and windowpanes kill many screech owls, the earlier especially while feeding on road-side rodents and road kills.[34][35]

This species has the potential to be infected by several parasites, including Plasmodium elongatum, Plasmodium forresteri, and Plasmodium gundersi.

The eastern screech owl (Megascops asio) or eastern screech-owl, is a small owl that is relatively common in Eastern North America, from Mexico to Canada. This species is native to most wooded environments of its distribution, and more so than any other owl in its range, has adapted well to manmade development, although it frequently avoids detection due to its strictly nocturnal habits.