en

names in breadcrumbs

A recent genetic study suggests that the C. simensis is more closely related to gray wolves and coyotes than any other African canid (jackals, foxes, wild dogs). It is hypothesized that C. simensis is an evolutionary remnant of a past invasion of North Africa by gray wolf-life ancestors (Gottelli et al. 1994).

Perception Channels: tactile ; chemical

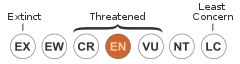

Ethiopian wolves are considered endangered by both the IUCN and U.S. Endangered Species Act. They are protected from hunting under Ethiopian law. Effort to curb the transmission of diseases, especially rabies, to Ethiopian wolves from domestic dogs and to prevent hybridization with domestic dogs have been undertaken. In addition, monitoring of Ethiopian wolf populations continues. (Sillero-Zubiri and Marino, 1995)

US Federal List: endangered

CITES: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: endangered

The Ethiopian wolf occasionally preys on lambs (Sillero-Zubiri 1995).

Canis simensis helps control populations of rodents in its habitat.

Ethiopian wolves are top predators in the ecosystems in which they live.

Canis simensis is a carnivore, generally preying on rodents ranging in size from the giant mole-rat Tachyoryctes macrocephalus (900 g) to that of the common grass rats (Arvicanthis blicki, Lophuromys melanonyx; 90-120 g) (Ginsberg and Macdonald 1990). In 689 feces, murid rodents accounted for 95.8% of all prey items, and 86.6% belonged to the three species listed above (Sillero-Zubiri and Gottelli 1994). When present in the hunting range, giant mole-rats are the primary component of the diet. In its absence, the common mole-rat Tachyoryctes splendens is most commonly eaten (Malcom 1997). Canis simensis also eats goslings, eggs, and young ungulates (reedbuck and mountain nyla) and occasionally scavenges carcasses. The Ethiopian wolf often caches its prey in shallow holes (Ginsberg and Macdonald 1990).

Prey is usually captured by digging it out of burrows. Areas of high prey density are patrolled by wolves walking slowly. Once prey is located, the wolf moves stealthily towards it and grabs it with its mouth after a short dash. Occasionally, the Ethiopian wolf hunts cooperatively to bring down young antelopes, lambs, and hares (Sillero-Zubiri and Gottelli 1994).

Animal Foods: birds; mammals; eggs; carrion

Foraging Behavior: stores or caches food

Primary Diet: carnivore (Eats terrestrial vertebrates)

The Ethiopian wolf has a very restricted range. It is found only in six or seven mountain ranges of Ethiopia. This includes the Arssi and Bale mountains of southeast Ethiopia, the Simien mountains, northeast Shoa, Gojjam, and Mt. Guna (Ginsberg and Macdonald 1990). The largest population exists in the Bale Mountains National Park with 120-160 individuals (Sillero-Zubiri and Gottelli 1995).

Biogeographic Regions: ethiopian (Native )

Canis simensis is found in afro-alpine grasslands and heathlands where vegetation is less than 0.25 m high. It lives at altitudes of 3000-4400 m (Sillero-Zubiri and Gottelli 1994).

Range elevation: 3000 to 4400 m.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: savanna or grassland ; mountains

Ethiopian wolves may live 8 to 10 years in the wild, although one wild individual was recorded living to 12 years. (Sillero-Zubiri and Marino, 1995)

Range lifespan

Status: wild: 12 (high) years.

Typical lifespan

Status: wild: 10 (high) years.

Ethiopian wolves are long-limbed, slender looking canids. They have a reddish coat with white marking on the legs, underbelly, tail, face, and chin. The boundary between the red and white fur is quite distinct. White markings on the face include a characteristic white crescent below the eyes and a white spot on the cheeks. The chin and throat are also white. The tail is marked with an indistinct black stripe down its length and a brush of black hairs at the tip. The ears are wide and pointed and the nose, gums, and palate are black. Females are generally paler in color than males and are smaller overall. There are five toes on the front feet and four on the rear feet. Males measure from 928 to 1012 mm (average 963 mm) and females from 841 to 960 mm (average 919 mm). Males weigh from 14.2 to 19.3 kg (average 16.2) and females from 11.2 to 14.2 kg (average 12.8). The tail is from 270 to 396 mm in length. The dental formula is 3/3:1/1:4/4:2/3, with the lower third molar being absent occasionally. (Sillero-Zubiri and Marino, 1995)

Range mass: 11.2 to 19.3 kg.

Range length: 841 to 1012 mm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: male larger

For Ethiopian wolves, dispersal from their native packs is limited due to habitat saturation. Males generally remain in their natal pack, and a small number of females disperse in their second or third year. To combat this high potential for inbreeding inside the closely related pack, matings outside the pack occur frequently. Copulation outside the pack occurs with males of all rank, but those within the pack occur only between the dominant male and female. While copulation between males and subordinate females does occur, pups that may arise from this union rarely survive (Sillero-Zubiri et al. 1996).

Prior to copulation, the dominant female increases her rate of scent marking, play soliciting, food begging towards the dominant male, and aggressive behavior towards subordinate females. Ethiopian wolves mate over a period of 3-5 days, involving a copulation tie that lasts up to 15 minutes.

It is not uncommon for a subordinate female to assist in suckling the young of the dominant female. In these cases, the subordinate lactating female is likely pregnant and either loses or deserts her own young for those of the dominant female.

Mating System: monogamous ; cooperative breeder

Once a year between October and January, the dominant female in each pack gives birth to a litter of 2-6 pups. Gestation lasts approximately 60-62 days. The female gives birth to her litter in a den she digs in open ground under a boulder or in a rocky crevice. The pups are born with their eyes closed and no teeth. They are charcoal gray with a buff patch on their chest and under areas. At about 3 weeks, the coat begins to be replaced by the normal adult coloring and the young first emerge from the den. After this time, den sites are regularly shifted, sometimes up to 1300m.

Development of the young occurs in three stages (Sillero-Zubiri and Gottelli 1994). The first covers weeks 1-4 when the pups are completely dependent on their mother for milk. The second occurs from week 5-10 from when the pups' milk diet is supplemented by solid food regurgitated from all pack members. It ends when the pups are completely weaned. Finally, from week 10 until about 6 months, the young survive almost solely on solid food provided from adult members of the pack. Adults have been seen providing food for young up to 1 year old. The Ethiopian wolf attains full adult appearance at 2 years of age, and both sexes are sexually mature during their second year (Sillero-Zubiri and Gottelli 1994). Data on life expectancy is inadequate, but C. simensis is likely to live 8-9 years in the wild (Macdonald 1984).

Range number of offspring: 2 to 6.

Range gestation period: 60 to 62 days.

Average weaning age: 70 days.

Key Reproductive Features: gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual

Parental Investment: altricial ; post-independence association with parents; extended period of juvenile learning

Həbəşistan çaqqalı (lat. Canis simensis) - canavar cinsinə aid heyvan növü.

El xacal d'Etiòpia (Canis simensis) és el cànid més amenaçat d'extinció. Només viu als herbassars i les landes de tipus alpí d'Etiòpia. El seu nom vulgar és degut al fet que durant molt de temps es cregué que era un xacal, però actualment se sap que és més proper als llops.

El xacal d'Etiòpia (Canis simensis) és el cànid més amenaçat d'extinció. Només viu als herbassars i les landes de tipus alpí d'Etiòpia. El seu nom vulgar és degut al fet que durant molt de temps es cregué que era un xacal, però actualment se sap que és més proper als llops.

Vlček etiopský (Canis simensis nebo Simenia simensis) je velmi vzácná psovitá šelma, která žije pouze v Etiopii.

Tento nesmírně zajímavý vlček není poddruh vlka, ale jeho příbuzným, ačkoliv ještě donedávna se věřilo, že jde o druh lišky a to především díky jeho zvláštní stavbě těla a typicky liščím znakům jako jsou dlouhé uši, čenich a nohy, silný huňatý ocas a především hnědo rezaté zbarvení s kombinací bílých a černých skvrn na ocase a břichu.

Jde o jednu z menších psovitých šelem. V dospělosti dosahuje v kohoutku velikosti pouhých 60 centimetrů a hmotnost samců je maximálně 18 kilogramů. U samic platí stejné měřítko rozdílu mezi psy a fenami jako u všech psovitých šelem. Velikostí i hmotností je mnohem drobnější.

Jedním z důvodů je samozřejmě prostředí, ve kterém se vyvíjel a jehož drsné podmínky z něj učinily lehkého a vytrvalého lovce, schopného skrývat se v nízkých keřích a obratně se pohybovat na skalnatém povrchu.

Existuje hned několik pojmenování pro toto podivné stvoření: pro svou podobnost s liškou byl dlouho označován jako liška habešská, domorodci jej nazývají ky kebero, což znamená červený šakal.

I přesto, že není nikterak významným zástupcem psovitých šelem, je výjimečný hned v několika bodech: vyskytuje se pouze ve dvou velmi malých oblastech Afriky - přesněji Etiopie, jak název napovídá. Sem se dostal již na konci poslední doby ledové z oblastí západní Evropy a dnešního Ruska. Žije na horských pustinách v nadmořské výšce až 4 000 m.

Vlčci se specializovali na lov velkých hlodavců, mláďat větších savců a také patří mezi mrchožrouty, čímž stejně jako jiní psovití funguje v tamějším ekosystému jako strážce rovnováhy a „eliminátor“ slabých jedinců, kteří by beztak uhynuli. Tento přirozený stav věcí se však drasticky mění díky činnosti člověka, jehož stáda dobytka spásají a ničí prostředí, ve kterém se zdržuje přirozená kořist vlčka. Jeho další výjimečnou vlastností, která však napomáhá vyhubení je fakt, že vlček etiopský nemá přirozený strach z lidí, a tak se stává snadným terčem. Dnešní populace je odhadována na pouhých 500 - 600 jedinců a řadí se tak mezi ohrožené druhy.

Co se týče jejich společenského života, i tady existuje velká zvláštnost. Vlček etiopský je ve dne lovec samotář a po setmění se instinktivně sdružuje do smeček o maximálně sedmi jedincích, aby si zajistil bezpečí.

Páří se na přelomu podzimu a zimy. Vrh čítá přibližně sedm vlčků, jejichž rodiči může být pouze alfa-pár (vůdci smečky - samec s družkou) a jejich výchova začíná v norách a za přítomnosti členů smečky, což jsou již shodné znaky s ostatními psovitými.

Vlčky ohrožují ničení životního prostředí, choroby a pronásledování ze strany lidí. Organizace na ochranu přírody mají proti tradičním zvykům etiopských obyvatel malou šanci na zlepšení situace, ale doufají, že cílenými ochrannými prostředky a sledováním jednotlivých smeček dospějí alespoň ke stagnaci přežívajících kusů a zajištění jejich klidného rozmnožování.

Vlček etiopský (Canis simensis nebo Simenia simensis) je velmi vzácná psovitá šelma, která žije pouze v Etiopii.

Abessinsk ræv (Canis simensis), også kaldet caberu eller etiopisk ulv, er et rovdyr i hundefamilien. Den når en længde på 1 meter med en hale på 33 cm og vejer 15-18 kg. Abessinsk ræv lever i Etiopiens højland, hvor den er totalfredet, men det er svært at følge op på i praksis. Den regnes i dag som verdens mest truede medlem af hundefamilien. Der formodes blot at være omkring tre bestande tilbage, bestående af mindre end 500 individer, og arten er truet.

Abessinsk ræv (Canis simensis), også kaldet caberu eller etiopisk ulv, er et rovdyr i hundefamilien. Den når en længde på 1 meter med en hale på 33 cm og vejer 15-18 kg. Abessinsk ræv lever i Etiopiens højland, hvor den er totalfredet, men det er svært at følge op på i praksis. Den regnes i dag som verdens mest truede medlem af hundefamilien. Der formodes blot at være omkring tre bestande tilbage, bestående af mindre end 500 individer, og arten er truet.

Der Äthiopische Wolf (Canis simensis) oder Äthiopische Schakal ist der seltenste aller Wildhunde. In älterer Literatur findet man dieses Tier unter dem Namen „Abessinischer Fuchs“, doch dies ist wegen seiner Hochbeinigkeit und seiner systematischen Stellung ein unpassender Name.

Die Gestalt ähnelt der eines Schakals. Der Äthiopische Wolf misst 1 m (Kopf-Rumpf-Länge) zuzüglich 30 cm Schwanz. Bis zur Schulter steht er 50 cm hoch. Sein Fell ist rotbraun, Kehle und Kinn sind weiß gefärbt. Die Schnauze ist lang gestreckt und fuchsartig. Sein Körpergewicht beträgt etwa 18 bis 20 Kilogramm.

Verbreitet ist der Äthiopische Wolf ausschließlich in einigen Gebirgen Äthiopiens und des östlichen Sudan. Zentrum der heutigen Verbreitung ist der Bale-Mountains-Nationalpark. Die Habitate sind hochalpin und befinden sich in baumlosen Höhen zwischen 3000 und 4400 m.

Da sich in diesen Regionen die Felder einheimischer Bauern zunehmend höher in die Gebirge schieben, wird diesem Wildhund zunehmend seine Nahrungsgrundlage entzogen, denn den neuentstehenden Nutzflächen müssen die nagetierreichen Grasflächen weichen. Nach einer Schätzung des Jahres 2006 gibt es nur noch etwa 700 Individuen dieser Art, die damit als stark bedroht einzustufen ist.

Der Äthiopische Wolf ist in seiner Ernährung weniger vielseitig als andere Hunde. Zu 96 % ernährt er sich von Mäusen und Ratten. Die Afrikanische Maulwurfsratte ist dabei seine Hauptbeute. Die restlichen 4 % des Nahrungsspektrums werden von Graumullen, anderen kleinen Nagern, Jungvögeln, Vogeleiern, Zwergantilopen und Aas abgedeckt. Meistens wird der Äthiopische Wolf seiner Beute habhaft, indem er sie aus ihrem Bau gräbt.

Wie auch andere Vertreter der Gattung Canis lebt der Äthiopische Wolf in Rudeln, die von einem Alpha-Paar geführt werden und aus zwei bis dreizehn Mitgliedern bestehen können. Gemeinsam patrouillieren sie jeden Morgen an den Grenzen ihrer Reviere. Trotzdem geht der Äthiopische Wolf anschließend allein auf die Pirsch und nutzt bei der Jagd nicht die Überlegenheit einer Gruppe für den Nahrungserwerb. Oft lauern sie eher nach Katzenart bewegungslos vor einem Bau, bis ihre Beute aus dem Loch kommt und springen dann ihr Opfer an.

Im Gegensatz zu den meisten anderen Wildhunden ist er tagaktiv.

Lycaon pictus (Afrikanischer Wildhund)

Cuon alpinus (Rothund)

Canis aureus (Goldschakal)

Canis simensis (Äthiopischer Wolf)

Canis anthus (Afrikanischer Goldwolf)

Canis latrans (Kojote)

Canis lupus (Wolf; + Haushund)

Canis mesomelas (Schabrackenschakal)

Canis adustus (Streifenschakal)

Der Äthiopische Wolf wird der Gattung der Wolfs- und Schakalartigen (Canis) als Canis simensis zugeordnet.[2] Dabei werden mit der Nominatform Canis simensis simensis sowie C. simensis citernii zwei Unterarten unterschieden.[2][3]

Im Rahmen der Vorstellung der Genomsequenz des Haushundes wurde von Lindblad-Toh et al. 2005 eine phylogenetische Analyse der Hunde (Canidae) auf der Basis molekularbiologischer Daten veröffentlicht. Der Äthiopische Wolf wird dabei einer Klade aus dem Goldschakal (C. aureus), dem Kojoten (C. latrans) sowie dem Wolf (C. lupus) und dem Haushund (C. lupus familiaris) gegenübergestellt. Im Rahmen dieser Darstellung wurde die Monophylie der Wolfs- und Schakalartigen (Gattung Canis) angezweifelt, da der Streifenschakal (Canis adustus) und der Schabrackenschakal (Canis mesomelas) als Schwesterarten als basalste Arten allen anderen Vertretern der Gattung sowie zusätzlich dem Rothund (Cuon alpinus) und dem Afrikanischen Wildhund (Lycaon pictus) gegenübergestellt werden.[4] Diese beiden Arten müssten entsprechend in die Gattung Canis aufgenommen werden, damit sie als monophyletische Gattung Bestand hat.

Der Äthiopische Wolf wird von der International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) als bedroht (endangered) eingestuft.[3] Neben der zunehmenden Verringerung der Nahrungsgrundlage sind Krankheiten wie Tollwut und Staupe das größte Problem für den Äthiopischen Wolf. Diese Krankheiten wurden und werden auch aktuell von den herumstreunenden Hunden der Hirten eingeschleppt. Ein Ausbruch der Tollwut dezimierte 1990 in nur zwei Wochen die bis dato größte Population von ca. 440 Tieren auf unter 160, ein weiterer Ausbruch erfolgte im Jahre 2003.

Claudio Sillero-Zubiri, ein Zoologe von der University of Oxford, und Alastair Nelson von der Zoologischen Gesellschaft Frankfurt bemühen sich nunmehr um die Erhaltung der Art, insbesondere durch ihren Einsatz für eine Impfung gegen Tollwut. Da jedoch in Äthiopien eine Schluckimpfung in Form der in Europa üblichen Anwendung von mit dem notwendigen Impfstoff versehenen Ködern nicht zugelassen ist, versuchte man zunächst, jedes einzelne Tier für eine Impfinjektion einzufangen. Doch dieser Aufwand war von den Teams kaum zu schaffen, weshalb man dazu übergegangen ist, an Stelle der Wölfe die Hunde der Hirten zu impfen.

Ende 2008 ist es erneut zu einem Tollwutausbruch gekommen. Derzeit geht man davon aus, dass noch etwa 500 Individuen dieser Art leben. Zum Schutz der Art wurden im Lande sieben Schutzgebiete ausgewiesen. Des Weiteren laufen mehrere Forschungsprojekte, um weitere Schutzmaßnahmen für die Art zu ermöglichen.

Der Äthiopische Wolf (Canis simensis) oder Äthiopische Schakal ist der seltenste aller Wildhunde. In älterer Literatur findet man dieses Tier unter dem Namen „Abessinischer Fuchs“, doch dies ist wegen seiner Hochbeinigkeit und seiner systematischen Stellung ein unpassender Name.

Canis simensis — від клясы сысуноў атрада драпежных сямейства сабачых.

Даўжыня цела 84-100 см, даўжыня хваста 27—40 см; маса дарослых 11-20 кг, вышыня 53—62 см. Вушы шырокія і вострыя. Пыса вострая. Ногі і пыса доўгія. Хвост кароткі.

Canis simensis — від клясы сысуноў атрада драпежных сямейства сабачых.

Ο αιθιοπικός λύκος (Canis simensis), επίσης γνωστός και ως αβησσυνιακός λύκος, είναι κυνίδης που προέρχεται από τα Αιθιοπικά Υψίπεδα. Είναι παρόμοιος με το κογιότ σε μέγεθος και σωματική κατασκευή, και διακρίνεται από το μακρύ και στενό κρανίο του και την κόκκινη και λευκή του γούνα.[1] Σε αντίθεση με τους περισσότερους μεγάλους κυνίδες, οι οποίοι είναι πολυπληθείς και δεν περιορίζονται στο τι θα φάνε, ο αιθιοπικός λύκος περιορίζεται εξαιρετικά στο να τρώει αφροαλπικά τρωκτικά με πολύ συγκεκριμένες απαιτήσεις ενδιαιτημάτων. Είναι ένας από τους σπανιότερους κυνίδες του κόσμου και από τα πιο απειλούμενα με εξαφάνιση σαρκοφάγα της Αφρικής.

Η τρέχουσα περιοχή των ειδών περιορίζεται σε επτά απομονωμένες οροσειρές σε υψόμετρα 3.000-4.500 μ., με τον συνολικό πληθυσμό ενηλίκων να εκτιμάται σε 360-440 αιθιοπικούς λύκους το 2011, περισσότεροι από τους μισούς στα όρη Μπέιλ.[2]

Ο Αιθιοπικός λύκος αναγράφεται ως απειλούμενος από την IUCN, λόγω του μικρού του αριθμού και της κατακερματισμένης περιοχής. Οι απειλές περιλαμβάνουν την αύξηση πίεσης από την επέκταση των ανθρώπινων πληθυσμών, με αποτέλεσμα την υποβάθμιση των ενδιαιτημάτων μέσω της υπερβόσκησης, και τη μετάδοση ασθενειών και τη διασταύρωση από ελεύθερα σκυλιά. Η διατήρησή του διευθύνεται από το Πρόγραμμα Διατήρησης του Αιθιοπικού Λύκου του Πανεπιστημίου της Οξφόρδης, το οποίο επιδιώκει να προστατεύσει τους λύκους μέσω προγραμμάτων εμβολιασμού και κοινοτικής προσέγγισης.

Ο αιθιοπικός λύκος (Canis simensis), επίσης γνωστός και ως αβησσυνιακός λύκος, είναι κυνίδης που προέρχεται από τα Αιθιοπικά Υψίπεδα. Είναι παρόμοιος με το κογιότ σε μέγεθος και σωματική κατασκευή, και διακρίνεται από το μακρύ και στενό κρανίο του και την κόκκινη και λευκή του γούνα. Σε αντίθεση με τους περισσότερους μεγάλους κυνίδες, οι οποίοι είναι πολυπληθείς και δεν περιορίζονται στο τι θα φάνε, ο αιθιοπικός λύκος περιορίζεται εξαιρετικά στο να τρώει αφροαλπικά τρωκτικά με πολύ συγκεκριμένες απαιτήσεις ενδιαιτημάτων. Είναι ένας από τους σπανιότερους κυνίδες του κόσμου και από τα πιο απειλούμενα με εξαφάνιση σαρκοφάγα της Αφρικής.

Η τρέχουσα περιοχή των ειδών περιορίζεται σε επτά απομονωμένες οροσειρές σε υψόμετρα 3.000-4.500 μ., με τον συνολικό πληθυσμό ενηλίκων να εκτιμάται σε 360-440 αιθιοπικούς λύκους το 2011, περισσότεροι από τους μισούς στα όρη Μπέιλ.

Ο Αιθιοπικός λύκος αναγράφεται ως απειλούμενος από την IUCN, λόγω του μικρού του αριθμού και της κατακερματισμένης περιοχής. Οι απειλές περιλαμβάνουν την αύξηση πίεσης από την επέκταση των ανθρώπινων πληθυσμών, με αποτέλεσμα την υποβάθμιση των ενδιαιτημάτων μέσω της υπερβόσκησης, και τη μετάδοση ασθενειών και τη διασταύρωση από ελεύθερα σκυλιά. Η διατήρησή του διευθύνεται από το Πρόγραμμα Διατήρησης του Αιθιοπικού Λύκου του Πανεπιστημίου της Οξφόρδης, το οποίο επιδιώκει να προστατεύσει τους λύκους μέσω προγραμμάτων εμβολιασμού και κοινοτικής προσέγγισης.

အီသီယိုးပီးယား ဝံပုလွေ (Ethiopian wolf ) သိပ္ပံအမည် (Canis simensis) သည် အာဖရိကတွင် ကျင်လည်ကျက်စားသော ခွေးမျိုးရင်းဝင် သတ္တဝါ ဖြစ်သည်။ အင်္ဂလိပ်ဘာသာတွင် Abyssinian wolf ၊ Abyssinian fox၊ red jackal၊ Simien fox၊ Simien jackal စသည်ဖြင့် အမည်အမျိုးမျိုး ခေါ်ကြသည်။ မြေခွေးနှင့် နှိုင်းယှဉ်လျှင် ဝံပုလွေနှင့် ပို၍ ဆင်တူသည်ဟု ယူဆကြသည်။ အီသီယိုးပီးယား ဝံပုလွေများကို အမြင့်ပေ ၉၈၀၀ ကျော် (၃၀၀၀ မီတာကျော်) အီသီယိုးပီးယားနိုင်ငံရှိ အာဖရိကအယ်လ်ပ် တောင်တန်း ဒေသများတွင် တွေ့ရတတ်သည်။ ဂေဟစနစ်အတွင်း အမဲလိုက်သည့် သတ္တဝါများတွင် ထိပ်ဆုံးနေရာမှ ရှိသည်။ ထို သတ္တဝါသည် မျိုးသုဉ်းပျောက်ကွယ်ရန် အစိုးရိမ်ရဆုံး အခြေအနေတွင် ရှိ၍ အုပ်စု ၇ စုသာကျန်ပြီး ကောင်ရေ ၅၅၀ ခန့်သာ ကျန်ရှိတော့သည်။ အများဆုံးအကောင် အစုအဝေးကို အီသီယိုးပီးယားနိုင်ငံ တောင်ပိုင်း ဘာလေးတောင်တန်း ဒေသတွင် တွေ့ရပြီး နိုင်ငံမြောက်ပိုင်း ဆီမီယန်းတောင်တန်း ဒေသများတွင်လည်း အချို့ကို တွေ့ရကာ အခြားနေရာများတွင် အနည်းငယ်သာ ရှိသည်။ ဘာလေးတောင်တန်း အမျိုးသားဥယျာဉ်တွင် ကောင်ရေ ၄၄၀ ရှိရာမှ ၁၉၉၀ ခွေးရူးရောဂါ ပျံ့နှံ့မှုကြောင့် ၂ ပတ်အတွင်း ကောင်ရေ ၁၆၀ သာ ကျန်ရှိတော့သည်။

အီသီယိုးပီးယား ဝံပုလွေ (Ethiopian wolf ) သိပ္ပံအမည် (Canis simensis) သည် အာဖရိကတွင် ကျင်လည်ကျက်စားသော ခွေးမျိုးရင်းဝင် သတ္တဝါ ဖြစ်သည်။ အင်္ဂလိပ်ဘာသာတွင် Abyssinian wolf ၊ Abyssinian fox၊ red jackal၊ Simien fox၊ Simien jackal စသည်ဖြင့် အမည်အမျိုးမျိုး ခေါ်ကြသည်။ မြေခွေးနှင့် နှိုင်းယှဉ်လျှင် ဝံပုလွေနှင့် ပို၍ ဆင်တူသည်ဟု ယူဆကြသည်။ အီသီယိုးပီးယား ဝံပုလွေများကို အမြင့်ပေ ၉၈၀၀ ကျော် (၃၀၀၀ မီတာကျော်) အီသီယိုးပီးယားနိုင်ငံရှိ အာဖရိကအယ်လ်ပ် တောင်တန်း ဒေသများတွင် တွေ့ရတတ်သည်။ ဂေဟစနစ်အတွင်း အမဲလိုက်သည့် သတ္တဝါများတွင် ထိပ်ဆုံးနေရာမှ ရှိသည်။ ထို သတ္တဝါသည် မျိုးသုဉ်းပျောက်ကွယ်ရန် အစိုးရိမ်ရဆုံး အခြေအနေတွင် ရှိ၍ အုပ်စု ၇ စုသာကျန်ပြီး ကောင်ရေ ၅၅၀ ခန့်သာ ကျန်ရှိတော့သည်။ အများဆုံးအကောင် အစုအဝေးကို အီသီယိုးပီးယားနိုင်ငံ တောင်ပိုင်း ဘာလေးတောင်တန်း ဒေသတွင် တွေ့ရပြီး နိုင်ငံမြောက်ပိုင်း ဆီမီယန်းတောင်တန်း ဒေသများတွင်လည်း အချို့ကို တွေ့ရကာ အခြားနေရာများတွင် အနည်းငယ်သာ ရှိသည်။ ဘာလေးတောင်တန်း အမျိုးသားဥယျာဉ်တွင် ကောင်ရေ ၄၄၀ ရှိရာမှ ၁၉၉၀ ခွေးရူးရောဂါ ပျံ့နှံ့မှုကြောင့် ၂ ပတ်အတွင်း ကောင်ရေ ၁၆၀ သာ ကျန်ရှိတော့သည်။

The Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis),[3] also called the Simien jackal and Simien fox, is a canine native to the Ethiopian Highlands. In southeastern Ethiopia it is also known as the horse jackal. It is similar to the coyote in size and build, and is distinguished by its long and narrow skull, and its red and white fur.[4] Unlike most large canids, which are widespread, generalist feeders, the Ethiopian wolf is a highly specialised feeder of Afroalpine rodents with very specific habitat requirements.[5] It is one of the world's rarest canids, and Africa's most endangered carnivore.[6]

The species's current range is limited to seven isolated mountain ranges at altitudes of 3,000–4,500 m, with the overall adult population estimated at 360–440 individuals in 2011, more than half of them in the Bale Mountains.[1][7]

The Ethiopian wolf is listed as endangered by the IUCN, on account of its small numbers and fragmented range. Threats include increasing pressure from expanding human populations, resulting in habitat degradation through overgrazing, and disease transference and interbreeding from free-ranging dogs. Its conservation is headed by Oxford University's Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme, which seeks to protect wolves through vaccination and community outreach programs.[1]

Alternative English names for the Ethiopian wolf include the Simenian fox, the Simien jackal,[8] Ethiopian jackal, and Abyssinian wolf.[8]

The species was first scientifically described in 1835 by Eduard Rüppell,[12] who provided a skull for the British Museum.[13][14] European writers traveling in Ethiopia during the mid-19th century (then called Abyssinia) wrote that the animal's skin was never worn by natives, as it was popularly believed that the wearer would die should any wolf hairs enter an open wound,[15] while Charles Darwin hypothesised that the species gave rise to greyhounds.[16][b] Since then, it was scarcely heard of in Europe up until the early 20th century, when several skins were shipped to England by Major Percy Horace Gordon Powell-Cotton during his travels in Abyssinia.[13][14]

The Ethiopian wolf was recognised as requiring protection in 1938, and received it in 1974. The first in-depth studies on the species occurred in the 1980s with the onset of the American-sponsored Bale Mountains Research Project. Ethiopian wolf populations in the Bale Mountains National Park were negatively affected by the political unrest of the Ethiopian Civil War, though the critical state of the species was revealed during the early 1990s after a combination of shooting and a severe rabies epidemic decimated most packs studied in the Web Valley and Sanetti Plateau. In response, the IUCN reclassified the species from endangered to critically endangered in 1994. The IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group advocated a three-front strategy of education, wolf population monitoring, and rabies control in domestic dogs. The establishment of the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme in Bale soon followed in 1995 by Oxford University, in conjunction with the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority (EWCA).[6]

Soon after, a further wolf population was discovered in the Central Highlands. Elsewhere, information on Ethiopian wolves remained scarce; although first described in 1835 as living in the Simien Mountains, the paucity of information stemming from that area indicated that the species was likely declining there, while reports from the Gojjam plateau were a century out of date. Wolves were recorded in the Arsi Mountains since the early 20th century, and in the Bale Mountains in the late 1950s. The status of the Ethiopian wolf was reassessed in the late 1990s, following improvements in travel conditions into northern Ethiopia. The surveys taken revealed local extinctions in Mount Choqa, Gojjam, and in every northern Afroalpine region where agriculture is well developed and human pressure acute. This revelation stressed the importance of the Bale Mountains wolf populations for the species' long-term survival, as well as the need to protect other surviving populations. A decade after the rabies outbreak, the Bale populations had fully recovered to pre-epizootic levels, prompting the species' downlisting to endangered in 2004, though it still remains the world's rarest canid, and Africa's most endangered carnivore.[6]

Although fossil records exist of wolf-like canids from Late Pleistocene Eurasia, no fossil records are known for the Ethiopian wolf. In 1994, a mitochondrial DNA analysis showed a closer relationship to the gray wolf and the coyote than to other African canids, and C. simensis may be an evolutionary relic of a gray wolf-like ancestor's past invasion of northern Africa from Eurasia.[18]

Due to the high density of rodents in their new Afroalpine habitat, the ancestors of the Ethiopian wolf gradually developed into specialised rodent hunters. This specialisation is reflected in the animal's skull morphology, with its very elongated head, long jaw, and widely spaced teeth. During this period, the species likely attained its highest abundance, and had a relatively continuous distribution. This changed about 15,000 years ago with the onset of the current interglacial, which caused the species' Afroalpine habitat to fragment, thus isolating Ethiopian wolf populations from each other.[5]

The Ethiopian wolf is one of five Canis species present in Africa, and is readily distinguishable from jackals by its larger size, relatively longer legs, distinct reddish coat, and white markings. John Edward Gray and Glover Morrill Allen originally classified the species under a separate genus, Simenia,[20] and Oscar Neumann considered it to be "only an exaggerated fox".[21] Juliet Clutton-Brock refuted the separate genus in favour of placing the species in the genus Canis, upon noting cranial similarities with the side-striped jackal.[22]

In 2015, a study of mitochondrial genome sequences and whole genome nuclear sequences of African and Eurasian canids indicated that extant wolf-like canids have colonised Africa from Eurasia at least five times throughout the Pliocene and Pleistocene, which is consistent with fossil evidence suggesting that much of African canid fauna diversity resulted from the immigration of Eurasian ancestors, likely coincident with Plio-Pleistocene climatic oscillations between arid and humid conditions. According to a phylogeny derived from nuclear sequences, the Eurasian golden jackal (Canis aureus) diverged from the wolf/coyote lineage 1.9 million years ago, and with mitochondrial genome sequences indicating the Ethiopian wolf diverged from this lineage slightly prior to that.[23]: S1 Further studies on RAD sequences found instances of Ethiopian wolves hybridizing with African golden wolves.[24]

In 2018, whole genome sequencing was used to compare members of the genus Canis. The study supports the African golden wolf being distinct from the golden jackal, and with the Ethiopian wolf being genetically basal to both. There are two genetically distinct African golden wolf populations that exist in northwestern and eastern Africa. This suggests that Ethiopian wolves – or a close and extinct relative – once had a much larger range within Africa to admix with other canids. There is evidence of gene flow between the eastern population and the Ethiopian wolf, which has led to the eastern population being distinct from the northwestern population. The common ancestor of both African golden wolf populations was a genetically admixed canid of 72% grey wolf and 28% Ethiopian wolf ancestry.[25]

As of 2005, two subspecies are recognised by Mammal Species of the World Volume Three (MSW3).[3]

The Ethiopian wolf is similar in size and build to North America's coyote; it is larger than the golden, black-backed, and side-striped jackals, and has comparatively longer legs. Its skull is very flat, with a long facial region accounting for 58% of the skull's total length. The ears are broad, pointed, and directed forward. The teeth, particularly the premolars, are small and widely spaced. The canine teeth measure 14–22 mm in length, while the carnassials are relatively small. The Ethiopian wolf has eight mammae, of which only six are functional. The front paws have five toes, including a dewclaw, while the hind paws have four. As is typical in the genus Canis, males are larger than females, having 20% greater body mass. Adults measure 841–1,012 mm (33.1–39.8 in) in body length, and 530–620 mm (21–24 in) in height. Adult males weigh 14.2–19.3 kg (31–43 lb), while females weigh 11.2–14.15 kg (24.7–31.2 lb).[4]

The Ethiopian wolf has short guard hairs and thick underfur, which provides protection at temperatures as low as −15 °C. Its overall colour is ochre to rusty red, with dense whitish to pale ginger underfur. The fur of the throat, chest and underparts is white, with a distinct white band occurring around the sides of the neck. There is a sharp boundary between the red coat and white marks. The ears are thickly furred on the edges, though naked on the inside. The naked borders of the lips, the gums and palate are black. The lips, a small spot on the cheeks and an ascending crescent below the eyes are white. The thickly furred tail is white underneath, and has a black tip, though, unlike most other canids, there is no dark patch marking the supracaudal gland. It moults during the wet season (August–October), and there is no evident seasonal variation in coat colour, though the contrast between the red coat and white markings increases with age and social rank. Females tend to have paler coats than males. During the breeding season, the female's coat turns yellow, becomes woolier, and the tail turns brownish, losing much of its hair.[4]

Animals resulting from Ethiopian wolf-dog hybridisation tend to be more heavily built than pure wolves, and have shorter muzzles and different coat patterns.[26]

The Ethiopian wolf is a social animal, living in family groups containing up to 20 adults (individuals older than one year), though packs of six wolves are more common. Packs are formed by dispersing males and a few females, which with the exception of the breeding female, are reproductively suppressed. Each pack has a well-established hierarchy, with dominance and subordination displays being common. Upon dying, a breeding female can be replaced by a resident daughter, though this increases the risk of inbreeding. Such a risk is sometimes circumvented by multiple paternity and extra-pack matings. The dispersal of wolves from their packs is largely restricted by the scarcity of unoccupied habitat.[27]

These packs live in communal territories, which encompass 6 km2 (2.3 sq mi) of land on average. In areas with little food, the species lives in pairs, sometimes accompanied by pups, and defends larger territories averaging 13.4 km2 (5.2 sq mi). In the absence of disease, Ethiopian wolf territories are largely stable, but packs can expand whenever the opportunity arises, such as when another pack disappears. The size of each territory correlates with the abundance of rodents, the number of wolves in a pack, and the survival of pups. Ethiopian wolves rest together in the open at night, and congregate for greetings and border patrols at dawn, noon, and evening. They may shelter from rain under overhanging rocks and behind boulders. The species never sleeps in dens, and only uses them for nursing pups. When patrolling their territories, Ethiopian wolves regularly scent-mark,[28] and interact aggressively and vocally with other packs. Such confrontations typically end with the retreat of the smaller group.[27]

The mating season usually takes place between August and November. Courtship involves the breeding male following the female closely. The breeding female only accepts the advances of the breeding male, or males from other packs. The gestation period is 60–62 days, with pups being born between October and December.[29] Pups are born toothless and with their eyes closed, and are covered in a charcoal-grey coat with a buff patch on the chest and abdomen. Litters consist of two to six pups, which emerge from their den after three weeks, when the dark coat is gradually replaced with the adult colouration. By the age of five weeks, the pups feed on a combination of milk and solid food, and become completely weaned off milk at the age of 10 weeks to six months.[4] All members of the pack contribute to protecting and feeding the pups, with subordinate females sometimes assisting the dominant female by suckling them. Full growth and sexual maturity are attained at the age of two years.[29] Cooperative breeding and pseudopregnancy have been observed in Ethiopian wolves.[30]

Most females disperse from their natal pack at about two years of age, and some become "floaters" that may successfully immigrate into existing packs. Breeding pairs are most often unrelated to each other, suggesting that female-biased dispersal reduces inbreeding.[31] Inbreeding is ordinarily avoided because it leads to a reduction in progeny fitness (inbreeding depression) due largely to the homozygous expression of deleterious recessive alleles.[32]

Unlike most social carnivores, the Ethiopian wolf tends to forage and feed on small prey alone. It is most active during the day, the time when rodents are themselves most active, though they have been observed to hunt in groups when targeting mountain nyala calves.[33] Major Percy-Cotton described the hunting behaviour of Ethiopian wolves as thus:

... they are most amusing to watch, when hunting. The rats, which are brown, with short tails, live in big colonies and dart from burrow to burrow, while the cuberow stands motionless till one of them shows, when he makes a pounce for it. If he is unsuccessful, he seems to lose his temper, and starts digging violently; but this is only lost labour, as the ground is honeycombed with holes, and every rat is yards away before he has thrown up a pawful.[34]

The technique described above is commonly used in hunting big-headed African mole-rats, with the level of effort varying from scratching lightly at the hole to totally destroying a set of burrows, leaving metre-high earth mounds.

Wolves in Bale have been observed to forage among cattle herds, a tactic thought to aid in ambushing rodents out of their holes by using the cattle to hide their presence.[4] Ethiopian wolves have also been observed forming temporary associations with troops of grazing geladas.[35] Solitary wolves hunt for rodents in the midst of the monkeys, ignoring juvenile monkeys, though these are similar in size to some of their prey. The monkeys, in turn, tolerate and largely ignore the wolves, although they take flight if they observe feral dogs, which sometimes prey on them. Within the troops, the wolves enjoy much higher success in capturing rodents than usual, perhaps because the monkeys' activities flush out the rodents, or because the presence of numerous larger animals makes it harder for rodents to spot a threat.[36]

The Ethiopian wolf is restricted to isolated pockets of Afroalpine grasslands and heathlands inhabited by Afroalpine rodents. Its ideal habitat extends from above the tree line around 3,200 to 4,500 m, with some wolves inhabiting the Bale Mountains being present in montane grasslands at 3,000 m. Although specimens were collected in Gojjam and northwestern Shoa at 2,500 m in the early 20th century, no recent records exist of the species occurring below 3,000 m. In modern times, subsistence agriculture, which extends up to 3,700 m, has largely restricted the species to the highest peaks.[37]

The Ethiopian wolf uses all Afroalpine habitats, but has a preference for open areas containing short herbaceous and grassland communities inhabited by rodents, which are most abundant along flat or gently sloping areas with poor drainage and deep soils. Prime wolf habitat in the Bale Mountains consists of short Alchemilla herbs and grasses, with low vegetation cover. Other favourable habitats consist of tussock grasslands, high-altitude scrubs rich in Helichrysum, and short grasslands growing in shallow soils. In its northern range, the wolf's habitat is composed of plant communities characterised by a matrix of Festuca tussocks, Euryops bushes, and giant lobelias, all of which are favoured by the wolf's rodent prey. Although marginal in importance, the ericaceous moorlands at 3,200–3,600 m in Simien may provide a refuge for wolves in highly disturbed areas.[37]

In the Bale Mountains, the Ethiopian wolf's primary prey are big-headed African mole-rats, though it also feeds on grass rats, black-clawed brush-furred rats, and highland hares. Other secondary prey species include vlei rats, yellow-spotted brush-furred rats, and occasionally goslings and eggs. Ethiopian wolves have twice been observed to feed on rock hyraxes, and mountain nyala calves. It will also prey on reedbuck calves.[38] In areas where the big-headed African mole-rat is absent, the smaller Northeast African mole-rat is targeted.[39] In the Simien Mountains, the Ethiopian wolf preys on Abyssinian grass rats. Undigested sedge leaves have occasionally been found in Ethiopian wolf stomachs. The sedge possibly is ingested for roughage or for parasite control. The species may scavenge on carcasses, but is usually displaced by free-ranging dogs and African golden wolves. It typically poses no threat to livestock, with farmers often leaving herds in wolf-inhabited areas unattended.[4]

Six current Ethiopian wolf populations are known. North of the Rift Valley, the species occurs in the Simien Mountains in Gondar, in the northern and southern Wollo highlands, and in Guassa Menz in north Shoa. It has recently become extinct in Gosh Meda in north Shoa and Mount Guna, and has not been reported in Mount Choqa for several decades. Southeast of the Rift Valley, it occurs in the Arsi and Bale Mountains.[40]

The Ethiopian wolf has been considered rare since it was first recorded scientifically. The species likely has always been confined to Afroalpine habitats, so it was never widespread. In historical times, all of the Ethiopian wolf's threats are both directly and indirectly human-induced, as the wolf's highland habitat, with its high annual rainfall and rich fertile soils, is ideal for agricultural activities. Its proximate threats include habitat loss and fragmentation (subsistence agriculture, overgrazing, road construction, and livestock farming), diseases (primarily rabies and canine distemper), conflict with humans (poisoning, persecution, and road kills), and hybridisation with dogs.[42]

Rabies outbreaks, stemming from infected dogs, have killed many Ethiopian wolves over the 1990s and 2000s. Two well-documented outbreaks in Bale, one in 1991 and another in 2008–2009, resulted in the die-off or disappearance of 75% of known animals. Both incidents prompted reactive vaccinations in 2003 and 2008–2009, respectively. Canine distemper is not necessarily fatal to wolves, though a recent increase in infection has occurred, with outbreaks of canine distemper having been detected in 2005–2006 in Bale and in 2010 across subpopulations.[43]

During the 1990s, wolf populations in Gosh Meda and Guguftu became extinct. In both cases, the extent of Afroalpine habitat above the limit of agriculture had been reduced to less than 20 km2. The EWCP team confirmed the extinction of a wolf population in Mt. Guna in 2011, whose numbers had been in single figures for several years. Habitat loss in the Ethiopian highlands is directly linked to agricultural expansion into Afroalpine areas. In the northern highlands, human density is among the highest in Africa, with 300 people per km2 in some localities, with almost all areas below 3,700 m having been converted into barley fields. Suitable areas of land below this limit are under some level of protection, such as Guassa-Menz and the Denkoro Reserve, or within the southern highlands, such as the Arsi and Bale Mountains. The most vulnerable wolf populations to habitat loss are those within relatively low-lying Afroalpine ranges, such as those in Aboi Gara and Delanta in North Wollo.[44]

Some Ethiopian wolf populations, particularly those in North Wollo, show signs of high fragmentation, which is likely to increase with current rates of human expansion. The dangers posed by fragmentation include increased contact with humans, dogs, and livestock, and further risk of isolation and inbreeding in wolf populations. Although no evidence of inbreeding depression or reduced fitness exists, the extremely small wolf population sizes, particularly those north of the Rift Valley, raise concerns among conservationists. Elsewhere, the Bale populations are fairly continuous, while those in Simien can still interbreed through habitat corridors.[45]

In the Simien Mountains National Park, human and livestock populations are increasing by 2% annually, with further road construction allowing easy access to peasants into wolf home ranges; 3,171 people in 582 households were found to be living in the park and 1,477 outside the park in October 2005. Although the area of the park has since been expanded, further settlement stopped, and grazing restricted, effective enforcement may take years. As of 2011, about 30,000 people live in 30 villages around and two within the park, including 4,650 cereal farmers, herders, woodcutters, and many others. In Bale there are numerous villages in and around the area, comprising over 8,500 households with more than 12,500 dogs. In 2007, the estimate of households within wolf habitat numbered 1,756. Because of the high number of dogs, the risk of infection in local wolf populations is high. Furthermore, intentional and unintentional brush fires are frequent in the ericaceous moorlands wolves inhabit.[46]

Although wolves in Bale have learned to use cattle to conceal their presence when hunting for rodents, the level of grazing in the area can adversely affect the vegetation available for the wolves' prey. Although no declines in wolf populations related to overgrazing have occurred, high grazing intensities are known to lead to soil erosion and vegetation deterioration in Afroalpine areas such as Delanta and Simien.[47]

Direct killings of wolves were more frequent during the Ethiopian Civil War, when firearms were more available. The extinction of wolves in Mt. Choqa was likely due to persecution. Although people living close to wolves in modern times believe that wolf populations are recovering, negative attitudes towards the species persist due to livestock predation. Wolves were largely unmolested by humans in Bale, as they were not considered threats to sheep and goats. However, they are perceived as threats to livestock elsewhere, with cases of retaliatory killings occurring in the Arsi Mountains. The Ethiopian wolf has not been recorded to be exploited for its fur, though in one case, wolf hides were used as saddle pads. It was once hunted by sportsmen, though this is now illegal. Vehicle collisions killed at least four wolves in the Sanetti Plateau since 1988, while two others were left with permanent limps. Similar accidents are a risk in areas where roads cut across wolf habitats, such as in Menz and Arsi.[26]

Management plans for hybridization with dogs involve sterilization of known hybrids.[48] Incidences of Ethiopian wolf-dog hybridization have been recorded in Bale's Web Valley. At least four hybrids were identified and sterilized in the area. Although hybridization has not been detected elsewhere, scientists are concerned that it could pose a threat to the wolf population's genetic integrity, resulting in outbreeding depression or a reduction in fitness, though this does not appear to have taken place.[26] Due to the female's strong preference to avoid inbreeding, hybridization could be the result of not finding any males who are not close relatives outside of dogs.

Encounters with African golden wolves (Canis lupaster) are usually agonistic, with Ethiopian wolves dominating African wolves if the latter enter their territories, and vice versa. Although African golden wolves are inefficient rodent hunters and thus not in direct competition with Ethiopian wolves, it is likely that heavy human persecution prevents the former from attaining numbers large enough to completely displace the latter.[49]

The Ethiopian wolf is not listed on the CITES appendices, though it is afforded full official protection under Ethiopia's Wildlife Conservation Regulations of 1974, Schedule VI, with the killing of a wolf carrying a two-year jail sentence.[1]

The species is present in several protected areas, including three areas in South Wollo (Bale Mountains National Park, Simien Mountains National Park, and Borena Sayint Regional Park), one in north Shoa (Guassa Community Conservation Area), and one in the Arsi Mountains National Park. Areas of suitable wolf habitat have recently increased to 87%, as a result of boundary extensions in Simien and the creation of the Arsi Mountains National Park.[1]

Steps taken to ensure the survival of the Ethiopian wolf include dog vaccination campaigns in Bale, Menz, and Simien, sterilization programs for wolf-dog hybrids in Bale, rabies vaccination of wolves in parts of Bale, community and school education programs in Bale and Wollo, contributing to the running of national parks, and population monitoring and surveying. A 10-year national action plan was formed in February 2011.[1]

The species' critical situation was first publicised by the Wildlife Conservation Society in 1983, with the Bale Mountains Research Project being established shortly after. This was followed by a detailed, four-year field study, which prompted the IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group to produce an action plan in 1997. The plan called for the education of people in wolf-inhabited areas, wolf population monitoring, and the stemming of rabies in dog populations. The Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme was formed in 1995 by Oxford University, with donors including the Born Free Foundation, Frankfurt Zoological Society, and the Wildlife Conservation Network.[1]

The overall aim of the EWCP is to protect the wolf's Afroalpine habitat in Bale, and establish additional conservation areas in Menz and Wollo. The EWCP carries out education campaigns for people outside the wolf's range to improve dog husbandry and manage diseases within and around the park, as well as monitoring wolves in Bale, south and north Wollo. The program seeks to vaccinate up to 5,000 dogs a year to reduce rabies and distemper in wolf-inhabited areas.[1]

In 2016, the Korean company Sooam Biotech was reported to be attempting to clone the Ethiopian wolf using dogs as surrogate mothers to help conserve the species.[50]

The Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis), also called the Simien jackal and Simien fox, is a canine native to the Ethiopian Highlands. In southeastern Ethiopia it is also known as the horse jackal. It is similar to the coyote in size and build, and is distinguished by its long and narrow skull, and its red and white fur. Unlike most large canids, which are widespread, generalist feeders, the Ethiopian wolf is a highly specialised feeder of Afroalpine rodents with very specific habitat requirements. It is one of the world's rarest canids, and Africa's most endangered carnivore.

The species's current range is limited to seven isolated mountain ranges at altitudes of 3,000–4,500 m, with the overall adult population estimated at 360–440 individuals in 2011, more than half of them in the Bale Mountains.

The Ethiopian wolf is listed as endangered by the IUCN, on account of its small numbers and fragmented range. Threats include increasing pressure from expanding human populations, resulting in habitat degradation through overgrazing, and disease transference and interbreeding from free-ranging dogs. Its conservation is headed by Oxford University's Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme, which seeks to protect wolves through vaccination and community outreach programs.

Etiopia lupo (Canis simensis), ankaŭ konata kiel abisina lupo, abisina vulpo, ruĝa ŝakalo aŭ semiena ŝakalo estas specio de kanisedoj, endemia en Afriko. Abundeco de ĝiaj nomoj montras longan necertecon pri taksonomia pozicio de la specio, sed laŭ la plej modernaj genetikaj esploroj ĝi estas pli parenca al lupoj de genro Canis ol al vulpoj, al kiuj ĝi similas aspekte. Etiopa lupo preferas altecon de pli ol 3000 metroj en montaraj regionoj de Etiopio,[2] kaj estas la ĉefa rabobesto de tiu ekologia sistemo. Ekologie ĝi estas la plej minacata specio el ĉiuj kanisedoj[3] kaj havas nur 7 populaciojn kun suma nombro de ĉirkaŭ 550 plenkreskuloj. La plej granda populacio situas en Bale-montaro en Oromio, suda Etiopio, sed kelkaj pli malgrandaj populacioj ekzistas en Semien-montaro en la nordo de la lando kaj en kelkaj aliaj areoj. Klopodoj savi tiun specion estas plej forte asociataj kun nomo de Claudio Sillero-Zubiri, zoologiisto el Universitato de Oksfordo. Ekzemple, li produktis vakcinon kontraŭ rabio por protekti la lupojn kontraŭ la malsano, kiun ili ricevis de lokaj hundoj. En 1990 epidemio de rabio malpliigis la plej grandan populacion de etiopia lupo en Nacia Parko de Bale-montaro de 440 ĝis nur 160 plenkreskaj specianoj dum malpli ol du semajnoj. Laboron pri konservo de la specio subtenas brita fonduso Born Free Foundation.

Je komenco de molekula esploro estis sugestoj ke la etiopia lupo estas posteulo de griza lupo,[4] sed pli modernaj esploroj pruvas ke tio ne estas ĝuste tiel. Kvankam etiopia lupo estas vere parenca al aliaj lupoj, ĝi plej probable diverĝiĝis antaŭ 3 aŭ 4 jarmilionoj.[5]

Etiopia lupo estas mezgranda kanisedo, iom simila al kojoto je grando kaj aspekto, kun longaj kruroj kaj malvasta, akra muzelo.[6] Averaĝe ĝi pezas ĉirkaŭ 19 kilogramojn,[3] kaj la iĉoj estas 20% pli grandaj ol la inoj.[6] La kranio estas plateca, kun dika kaj malalta frunto, kaj la cerba parto estas preskaŭ cilindra kun bone disvolvitaj parietostoj. La dentoj estas malgrandaj kaj inter ili estas grandaj spacoj rezulte de adaptiĝo al ĉaso de roduloj. La denta formulo estas 3.1.4.3 3.1.4.2 {displaystyle {frac {3.1.4.3}{3.1.4.2}}}

La felo de etiopia lupo estas oĥra ĝis rust-ruĝa sur la vizaĝo, oreloj kaj dorso, kaj blanka ĝis pale-flava sur la ventraj partoj de la korpo. Blankaj makuloj ankaŭ estas sur la vangoj kaj sub la okuloj. Kontrasto de ruĝaj kaj blankaj partoj kreskas kun aĝo kaj socia rango, kaj inoj ĝenerale havas pli palajn kolorojn. Dorsa parto de la vosto havas rufan strion, kiu finiĝas je peniko de nigraj haroj ĉe la pinto. La felo havas mallongan superfelon kaj dikan subfelon, kiu ebligas la lupon komforte travivi malvarmon ĝis −15 °C.

Kvankam etiopiaj lupoj plej ofte ĉasas rodulojn sole, ili vivas en grupoj kaj defendas sian komunan teritorion. Tio diferencigas ilin de aliaj sociemaj kanisedoj, kiuj formigas grupojn por komuna ĉaso de granda predo. En areoj de malgranda homa influo la grupo de etiopiaj lupoj konsistas, averaĝe, je 6 plenkreskuloj, 1–6 adoleskuloj kaj 1–13 idoj. Iĉoj kutime restas en sia denaska grupo tutan sian vivon, sed la inoj ofte forlasas ĝin en la aĝo de 2 jaroj kaj aliaĝas al aliaj grupoj por interŝanĝo de la genoj.[6] Iu grupo enhavas preskaŭ ĉiujn iĉojn kaj ankaŭ 1–2 inojn naskitajn en ĝi, dum la aliaj inoj devenas el aliaj grupoj. Averaĝe, la seksa distribuo en la grupo estas po 2.6 iĉoj por ino.[3]

Dum pariĝa sezono okazas sociaj kunvenoj inter malsamaj grupoj. Tiam konfliktoj ne oftas. En aliaj tempoj, tamen, ofte okazas alfrontumoj inter grupoj de najbaraj teritorioj ĉe la limoj. Dum la konflikto, etiopiaj lupoj produktas multajn blekojn kaj voĉigoj, kaj pli granda (t.e., pli laŭta) grupo forpelas la oponantojn. Fizika lukto preskaŭ neniam okazas.[3]

Plej kutime dominanta ino de la grupo malpermesas pariĝon kun si al ĉiuj iĉoj de la grupo krom la plej dominanta. Ŝi, tamen, volonte respondos kaj pariĝos kun iu ajn vaganta iĉo de alia grupo. Entute ĝis 70% pariĝoj okazas kun iĉoj de aliaj grupoj. Ĉiuj membroj de la grupo helpas nutri kaj protekti junulojn. Iam malpli dominantaj inoj laktas al idoj de la pli dominanta. Iu aparta ino naskas ne pli ol unufoje po jaro, naskante ĉiufoje de 2 ĝis 6 idojn. La periodo de gravedeco daŭras ĉirkaŭ 2 monatojn, kaj la nasko okazas en fosita nestego, sub granda ŝtono aŭ en roka krevaĵo. Plenkreskuloj regule transmetas idojn inter nestegoj aŭ aliaj rifuĝejoj, iam tra distancoj ĝis 1300 m.[3]

La dieto de etiopia lupo konsistas preskuax nur de tagaj roduloj. La esploroj montras, ke ĝis 96% de tuta kvanto de predo de etiopiaj lupoj estas roduloj, inter kiuj la plej grava manĝa risurco estas endemia grandakapa talpo-rato (Tachyoryctes macrocephalus).[3] En areoj, kie grandakapaj talpo-ratoj ne vivas, la lupoj ĉasas orient-afrikan talpo-raton (Tachyoryctes splendens). Inter alia notita predo troveblas nigraunga malglata rato (Lophuromys melanonyx), flavmakula malglata rato (Lophuromys flavopunctatus), herba rato de Blick (Arvicanthis blicki), diversaj vlejaj ratoj (Otomys Spp.), etiopia monta leporo (Lepus starcki), roka prokavio (Procavia capensis), junaj idoj de griza silvikapro (Sylvicapra grimmia), monta redunko (Redunca fulvorufula) kaj monta njalo (Tragelaphus buxtoni), kaj ankaŭ malgrandaj birdoj. Krome, etiopiaj lupoj foje manĝas foliojn de ciperacoj por helpi digestadon.[6]

Estas du konataj subspecioj de tiu afrotropisa specio :[1]

Kvankam pasinte etiopiaj lupoj estas timataj rabobestoj de bruto,[7] nun oni plej ofte ne konsideras ilin serioza danĝero. Foje, oni povas vidi ŝafojn kaj kaprojn paŝtantajn memstare en areoj, kie la lupoj troveblas. En sudaj areoj, kie estas nur malgrandaj populacioj de etiopia lupo, ĝiaj atakoj al brutaro estas tiom raraj, ke perdoj estas neglektindaj kompare al atakoj de ŝakaloj kaj makulaj hienoj.[6]

Kvankam etiopia lupo oficie estas protektata specio, mortigoj de lupoj ade okazis dum la Etiopia Enlanda Milito (1974-1991) kaj sekva periodo de nestabileco. Etiopiaj lupoj plej ofte ne estas ĉasataj por felo, kvankam okaze en provinco Wollo oni uzis lupajn haŭtojn por seltapiŝoj.[6]

Malsimile al aliaj lupoj, etiopia lupo estas apenaŭ reprezentata en folkloro aŭ tradicioj de homaj kulturoj, kun kiuj ili kunekzistas. La sola konata kultura referenco estas uzo de ĝia hepato en tradicia medicino de nordaj regionoj de la lando. Ĝi, tamen, estis menciata en etiopia literaturo ekde 13-a jarcento. Nun ĝi estas oficie agnoskita nacia simbolo de Etiopio kaj aperis en du serioj de poŝtmarkoj.[6]

Etiopia lupo (Canis simensis), ankaŭ konata kiel abisina lupo, abisina vulpo, ruĝa ŝakalo aŭ semiena ŝakalo estas specio de kanisedoj, endemia en Afriko. Abundeco de ĝiaj nomoj montras longan necertecon pri taksonomia pozicio de la specio, sed laŭ la plej modernaj genetikaj esploroj ĝi estas pli parenca al lupoj de genro Canis ol al vulpoj, al kiuj ĝi similas aspekte. Etiopa lupo preferas altecon de pli ol 3000 metroj en montaraj regionoj de Etiopio, kaj estas la ĉefa rabobesto de tiu ekologia sistemo. Ekologie ĝi estas la plej minacata specio el ĉiuj kanisedoj kaj havas nur 7 populaciojn kun suma nombro de ĉirkaŭ 550 plenkreskuloj. La plej granda populacio situas en Bale-montaro en Oromio, suda Etiopio, sed kelkaj pli malgrandaj populacioj ekzistas en Semien-montaro en la nordo de la lando kaj en kelkaj aliaj areoj. Klopodoj savi tiun specion estas plej forte asociataj kun nomo de Claudio Sillero-Zubiri, zoologiisto el Universitato de Oksfordo. Ekzemple, li produktis vakcinon kontraŭ rabio por protekti la lupojn kontraŭ la malsano, kiun ili ricevis de lokaj hundoj. En 1990 epidemio de rabio malpliigis la plej grandan populacion de etiopia lupo en Nacia Parko de Bale-montaro de 440 ĝis nur 160 plenkreskaj specianoj dum malpli ol du semajnoj. Laboron pri konservo de la specio subtenas brita fonduso Born Free Foundation.

El lobo etíope, lobo abisinio, chacal del Semién o caberú (Canis simensis) es una de las especies de cánidos más raras y amenazadas del planeta, pues su población total no llega a 550 individuos que se encuentran en varias áreas aisladas de las montañas de Etiopía, por encima de los 3000 m s. n. m. (metros sobre el nivel del mar). Estas áreas se reúnen en dos grupos mayores separados por el Gran Valle del Rift, constituyendo dos subespecies separadas: C. s. simensis al noroeste y C. s. citernii al sureste.

Por su aspecto recuerda más a un perro doméstico primitivo como el dingo que al típico lobo de Eurasia. Mide entre 90 y 100 cm (centímetros) de largo y entre 25 y 34 de altura sobre los hombros. El peso es de 11,5 kg (kilogramos) en las hembras y de 14 a 18,5 kg en los machos. El cuerpo es grácil, dotado de morro, orejas y patas largas. El pelaje es rojizo-anaranjado en casi todo el cuerpo, tornándose blanco en el interior de las orejas, en torno a los ojos, boca, garganta, vientre, pies, cara interna de las patas y de la cola. Esta última es poco larga y poblada, de color negro desde la mitad a la punta y blanco y rojo en el resto.

El hábitat característico de esta especie es el prado de tipo afro-alpino. Se alimenta casi exclusivamente de roedores, destacándose entre estos las ratas-topo gigantes (Tachyoryctes macrocephalus), que constituyen cerca del 40 % de los alimentos que ingieren. Complementan su dieta con liebres y carroña, aunque en muy raras ocasiones algunos individuos cooperan para dar muerte a antílopes y pequeñas cabras y ovejas domésticas. Salvando estas circunstancias excepcionales, los lobos etíopes pasan el día acechando roedores o destruyendo sus madrigueras para capturarlos, siempre en solitario. En las zonas donde sufren la persecución humana, estos animales abandonan sus hábitos diurnos y se vuelven crepusculares o nocturnos.

Los lobos etíopes viven en pequeños grupos, de marcada estructura jerárquica, que se componen de dos o más hembras y unos cinco machos emparentados. Marcan su territorio (5-15 m² —metros cuadrados—) con orina y heces y lo defienden de los intrusos. Existe una pareja dominante que se reproduce cada año y a la que los individuos subordinados ayudan en la cría de su prole. En raras ocasiones, las hembras subordinadas también se reproducen.

El lobo abisinio se separó en tiempos recientes del lobo de Eurasia y Norteamérica (Canis lupus), su pariente más cercano, después de que sus ancestros llegaran a Abisinia procedentes de Arabia. La presencia de perros cazadores como los licaones o lobos pintados impidió que los nuevos inmigrantes colonizasen las vastas sabanas africanas, forzando al lobo etíope a convertirse en un depredador de montaña especializado en la caza de roedores. Considerado en peligro de extinción por la IUCN, el lobo etíope tiene sus mayores amenazas en la destrucción de su hábitat natural, la hibridación con perros asilvestrados, la persecución directa de los ganaderos que lo consideran un peligro para sus rebaños y la transmisión de enfermedades foráneas como la rabia. En 1990, la población del parque nacional de las montañas Bale se redujo de 440 a 160 ejemplares en sólo dos semanas, precisamente por esta razón. Debido a ello, el zoólogo Claudio Sillero Zubiri, de la Universidad de Oxford, está trabajando activamente en una vacuna oral que proteja a los lobos etíopes de esta enfermedad que les transmiten sus parientes domésticos.

El lobo etíope, lobo abisinio, chacal del Semién o caberú (Canis simensis) es una de las especies de cánidos más raras y amenazadas del planeta, pues su población total no llega a 550 individuos que se encuentran en varias áreas aisladas de las montañas de Etiopía, por encima de los 3000 m s. n. m. (metros sobre el nivel del mar). Estas áreas se reúnen en dos grupos mayores separados por el Gran Valle del Rift, constituyendo dos subespecies separadas: C. s. simensis al noroeste y C. s. citernii al sureste.

Por su aspecto recuerda más a un perro doméstico primitivo como el dingo que al típico lobo de Eurasia. Mide entre 90 y 100 cm (centímetros) de largo y entre 25 y 34 de altura sobre los hombros. El peso es de 11,5 kg (kilogramos) en las hembras y de 14 a 18,5 kg en los machos. El cuerpo es grácil, dotado de morro, orejas y patas largas. El pelaje es rojizo-anaranjado en casi todo el cuerpo, tornándose blanco en el interior de las orejas, en torno a los ojos, boca, garganta, vientre, pies, cara interna de las patas y de la cola. Esta última es poco larga y poblada, de color negro desde la mitad a la punta y blanco y rojo en el resto.

El hábitat característico de esta especie es el prado de tipo afro-alpino. Se alimenta casi exclusivamente de roedores, destacándose entre estos las ratas-topo gigantes (Tachyoryctes macrocephalus), que constituyen cerca del 40 % de los alimentos que ingieren. Complementan su dieta con liebres y carroña, aunque en muy raras ocasiones algunos individuos cooperan para dar muerte a antílopes y pequeñas cabras y ovejas domésticas. Salvando estas circunstancias excepcionales, los lobos etíopes pasan el día acechando roedores o destruyendo sus madrigueras para capturarlos, siempre en solitario. En las zonas donde sufren la persecución humana, estos animales abandonan sus hábitos diurnos y se vuelven crepusculares o nocturnos.

Los lobos etíopes viven en pequeños grupos, de marcada estructura jerárquica, que se componen de dos o más hembras y unos cinco machos emparentados. Marcan su territorio (5-15 m² —metros cuadrados—) con orina y heces y lo defienden de los intrusos. Existe una pareja dominante que se reproduce cada año y a la que los individuos subordinados ayudan en la cría de su prole. En raras ocasiones, las hembras subordinadas también se reproducen.

El lobo abisinio se separó en tiempos recientes del lobo de Eurasia y Norteamérica (Canis lupus), su pariente más cercano, después de que sus ancestros llegaran a Abisinia procedentes de Arabia. La presencia de perros cazadores como los licaones o lobos pintados impidió que los nuevos inmigrantes colonizasen las vastas sabanas africanas, forzando al lobo etíope a convertirse en un depredador de montaña especializado en la caza de roedores. Considerado en peligro de extinción por la IUCN, el lobo etíope tiene sus mayores amenazas en la destrucción de su hábitat natural, la hibridación con perros asilvestrados, la persecución directa de los ganaderos que lo consideran un peligro para sus rebaños y la transmisión de enfermedades foráneas como la rabia. En 1990, la población del parque nacional de las montañas Bale se redujo de 440 a 160 ejemplares en sólo dos semanas, precisamente por esta razón. Debido a ello, el zoólogo Claudio Sillero Zubiri, de la Universidad de Oxford, está trabajando activamente en una vacuna oral que proteja a los lobos etíopes de esta enfermedad que les transmiten sus parientes domésticos.

Canis simensis edo Etiopiako otsoa, abisiniako otsoa, txakal gorria edo simiar txakala, Etiopiako gune menditsuetan bizi den Canidae bat da.

Simieninsakaali[3][4] (Canis simensis) on punaturkkinen koiraeläin, joka elää Etiopian ylängöllä. Laji tunnetaan myös nimillä etiopiankettu[3][5], simeninsakaali[5], simiensakaali[6] ja etiopiansusi[6]. Nisäkäsnimistötoimikunta ehdottanut lajille uutta nimeä etiopiansakaali[4]. Laji on nykyisin erittäin uhanalainen, koska sitä uhkaavat metsästys, elinalueiden supistuminen ja koirien levittämä raivotauti.

Simieninsakaalilla on kapea kuono ja pystyt, teräväkärkiset korvat. Hampaat ovat pienet ja yläleuan viimeiset välihampaat ovat samanlaiset kuin sudella. Turkki on yleisväriltään punertava. Selästä se on kellanpunainen, takaosaa päin tummeneva, ja vatsa on vaalea. Väriraja erottuu hyvin. Kaulan sivulla on kaksi kellanpunaista poikkijuovaa. Tiheäkarvainen häntä on ylhäältä ja alapinnalta punertavanvalkoinen, keskeltä tumma. Uros on naarasta kookkaampi. Ruumiin pituus on noin metri. Uros painaa 15–19 kiloa ja naaras 11–14 kiloa.

Simieninsakaali on nimestään huolimatta lähempää sukua sudelle ja kojootille kuin saman mantereen kulta-, vaippa- ja juovasakaaleille.[6] Sen arvellaan kehittyneen susista, jotka viime jääkaudella noin 12 000 vuotta sitten tulivat Afrikkaan ja jäivät eristyksiin alueen vuoristoon.

Simieninsakaali elää vain Etiopian alpiinisilla vuoristoniityillä 3 000–4 000 metrin korkeudessa. Laji on hävinnyt Eritreasta ja sen kanta on supistunut myös Etiopiassa rajusti. Tärkeimmät elinpaikat ovat Bale- ja Simienvuoristo. Sitä tavataan muun muassa Simienin kansallispuistossa.

Simieninsakaali elää pieninä laumoina, joissa on vain yksi lisääntyvä naaras. Pennut ovat usein useamman vieraan koiraan jälkeläisiä. Lauma merkitsee noin kuuden neliökilometrin laajuisen reviirin hajumerkeillä, kuten ulosteilla. Reviirin rajat tarkastetaan päivittäin ja mahdolliset tunkeilijat ajetaan pois. Lauman jäsenet pitävät yhteyttä toisiinsa ulvomalla ja kertovat samalla olemassaolostaan muille laumoille. Varoittaessaan tai uhkaillessaan simieninsakaali päästää lyhyitä ja hermostuneita haukahduksia.

Simieninsakaalit syövät pääasiassa jyrsijöitä, joita on ylängöllä runsaasti, jopa neljä tonnia neliökilometriä kohden. Paras saalis on juurirotta, mutta niille kelpaa mikä tahansa alueen yli kymmenestä jyrsijälajista. Sorkkaeläinten kimppuun se käy harvoin. Simieninsakaalin lisääntyminen poikkeaa muiden Canis-suvun koiraeläinten lisääntymisestä. Naaraat parittelevat yleensä eri laumojen urosten kanssa välttääkseen sisäsiittoisuutta, koska moni koiras jää synnyinlaumaan. Naaras synnyttää 60–62 vuorokauden kantoajan jälkeen 3–7 pentua pesäluolaan. Naaraat ovat lisääntymiskykyisiä kaksivuotiaina.

Simieninsakaali on nykyään erittäin uhanalainen, ja sen kanta on enää noin 500 yksilöä. Kanta on jakautunut useisiin pienempiin populaatioihin. Suurin populaatio on Bale-vuorten kansallispuistossa, jossa elää noin 200 yksilöä. Toinen tärkeä elinalue on Simienin kansallispuisto, jossa elää 50–100 eläintä. Elinalueet ovat pienentyneet ihmisasutuksen levitessä.

Lajia uhkaa metsästys turkin takia sekä vaino karjarosvona, vaikka sen aiheuttamaa uhkaa karjalle on liioiteltu vahvasti. Simieninsakaalit eivät pelkää ihmistä ja päästävät muutaman metrin päähän. Myös karja saattaa heikentää jyrsijäkantoja, jopa kansallispuistoissa. Kaikkein pahin uhka on kuitenkin karjankasvattajien koirien levittämä raivotauti ja penikkatauti. Tilannetta on yritetty parantaa rokottamalla koiria, koska sakaalit ovat herkkiä rokotteen yliannostukselle. Koirat myös lisääntyvät sakaalien kanssa ja uhkaavat näin lajin geeniperimää. Ainakin naarassakaalin ja uroskoiran lisääntymisestä tiedetään.[7]

Simieninsakaali (Canis simensis) on punaturkkinen koiraeläin, joka elää Etiopian ylängöllä. Laji tunnetaan myös nimillä etiopiankettu, simeninsakaali, simiensakaali ja etiopiansusi. Nisäkäsnimistötoimikunta ehdottanut lajille uutta nimeä etiopiansakaali. Laji on nykyisin erittäin uhanalainen, koska sitä uhkaavat metsästys, elinalueiden supistuminen ja koirien levittämä raivotauti.

Canis simensis

Le loup d'Éthiopie (Canis simensis), encore appelé Loup d'Abyssinie[1] en raison de l'ancien nom utilisé pour désigner l'Éthiopie, Cabéru, Chacal du Simien ou même kebero en amharique, est le troisième canidé le plus rare au monde (après le Renard de Darwin et le Loup rouge) avec une population totale estimée à moins de 500 individus à l'état sauvage, dont 300 dans le parc national du mont Balé (au centre de l’Éthiopie) et aucun en captivité. À ce titre il est donc classé espèce « en danger » par l'Union internationale pour la conservation de la nature (UICN).

Le loup d'Éthiopie est une espèce endémique des hauts plateaux éthiopiens situés à 3 000 mètres d'altitude environ. Ce représentant de la famille des canidés mesure environ 60 cm au garrot. Les mâles pèsent de 14 à 19 kg et de 11 à 14 kg pour les femelles. Les portées sont de 6 à 12 petits[2].

Ces loups, qui se nourrissent essentiellement de rongeurs (notamment en chassant le rat-taupe géant) vivent en groupes familiaux. Les loups d’une même meute se regroupent pour la nuit, mais ils se dispersent la journée pour chasser en solitaire[2].

Une partie importante des derniers représentants de l'espèce ont été victimes dans le parc national du mont Balé d'une épizootie. Entre fin septembre 2003 et janvier 2004, la rage a tué 65 individus parmi les loups, soit plus des trois quarts de la population de la région de la vallée du Web. La rage pourrait avoir été introduite par les chiens de bergers qui viennent faire paître leurs troupeaux dans le parc.

Les loups étant gravement menacés par cette épizootie de rage, un programme de vaccination soutenu financièrement par la CEPA a été mis en place dans la vallée du Web dès novembre 2003 par le Programme de conservation du loup d'Éthiopie[3]. Nyala Productions "« edia for the protection of wildlife » tente de soutenir l'EWCP dans son travail via la publication de reportages photographiques, de mini-films, de conférence, entre autres. Un projet de livre de photographies sur la région du parc national du mont Balé est également en cours pour attirer l'attention sur la fragilité des écosystèmes de cette région de la corne de l'Afrique.

Leurs effectifs ont été considérablement diminués ces dernières années, principalement du fait des maladies transmises par les chiens et l'augmentation de l'activité pastorale sur les hauts plateaux. Il ne resterait à l'heure actuelle qu'une douzaine de meutes, représentant environ 500 individus[3].

Canis simensis

Le loup d'Éthiopie (Canis simensis), encore appelé Loup d'Abyssinie en raison de l'ancien nom utilisé pour désigner l'Éthiopie, Cabéru, Chacal du Simien ou même kebero en amharique, est le troisième canidé le plus rare au monde (après le Renard de Darwin et le Loup rouge) avec une population totale estimée à moins de 500 individus à l'état sauvage, dont 300 dans le parc national du mont Balé (au centre de l’Éthiopie) et aucun en captivité. À ce titre il est donc classé espèce « en danger » par l'Union internationale pour la conservation de la nature (UICN).

O lobo etíope ou abisinio, chacal do Semién ou caberú (Canis simensis) é unha das especies de cánidos máis raras e ameazadas do planeta, pois a súa poboación total non chega a 550 individuos que se atopan en varias áreas illadas das montañas de Etiopía, por riba dos 3.000 msnm de altitude. Estas áreas reúnense en dous grupos maiores separados polo Gran Val do Rift, constituíndo dúas subespecies separadas: C.s. simensis ao noroeste e C.s. citernii ao sueste.

Polo seu aspecto lembra máis a un can doméstico primitivo como o dingo que ao típico lobo de Eurasia. Mide entre 90 e 100 centímetros de longo e entre 25 e 34 de altura sobre os ombreiros. O peso é de 11,5 kg nas femias e de 14 a 18,5 kg nos machos. O corpo é grácil, dotado de morro, orellas e patas longas. O pelame é avermellado-alaranxado en case todo o corpo, tornándose branco no interior das orellas, arredor dos ollos, boca, garganta, ventre, pés, cara interna das patas e da cola. Esta última é pouco longa e poboada, de cor negra desde a metade á punta e branca e vermella no resto.

O hábitat característico desta especie é o prado de tipo afro-alpino. Aliméntase case exclusivamente de roedores, destacando entre estes as ratas-toupa xigantes (Tachyoryctes macrocephalus), que constitúen preto do 40% dos alimentos que inxiren. Complementan a súa dieta con lebres e preas, aínda que en moi raras ocasións algúns individuos cooperan para dar morte a antílopes e pequenas cabras e ovellas domésticas. Salvando estas circunstancias excepcionais, os lobos etíopes pasan o día axexando roedores ou destruíndo os seus tobos para capturalos, sempre en solitario. Nas zonas onde sofren a persecución humana, estes animais abandonan os seus hábitos diúrnos e vólvense crepusculares ou nocturnos.

Os lobos etíopes viven en pequenos grupos, de marcada estrutura xerárquica, que se compoñen de dúas ou máis femias e uns cinco machos emparentados. Marcan o seu territorio (5-15 m²) con ouriños e feces e deféndeno dos intrusos. Existe unha parella dominante que se reproduce cada ano e á que os individuos subordinados axudan na cría da súa prole. En raras ocasións, as femias subordinadas tamén se reproducen.

O lobo abisinio separouse en tempos recentes do lobo de Eurasia e Norteamérica (Canis lupus), o seu parente máis próximo, despois de que os seus devanceiros chegasen a Abisinia procedentes de Arabia. A presenza de cans cazadores como os licaóns ou lobos pintados impediu que os novos inmigrantes colonizasen as vastas sabanas africanas, forzando ao lobo etíope a converterse nun depredador de montaña especializado na caza de roedores. Considerado en perigo de extinción pola IUCN, o lobo etíope ten as súas maiores ameazas na destrución do seu hábitat natural, a hibridación con cans asilvestrados, a persecución directa dos gandeiros que o consideran un perigo para os seus rabaños e a transmisión de enfermidades foráneas como a rabia. En 1990, a poboación do Parque Nacional das montañas Bale reduciuse de 440 a 160 exemplares en só dúas semanas, precisamente por esta razón. Debido a iso, o zoólogo Claudio Sillero Zubiri, da Universidade de Oxford, está a traballar activamente nunha vacina oral que protexa aos lobos etíopes desta enfermidade que lles transmiten os seus parentes domésticos.

O lobo etíope ou abisinio, chacal do Semién ou caberú (Canis simensis) é unha das especies de cánidos máis raras e ameazadas do planeta, pois a súa poboación total non chega a 550 individuos que se atopan en varias áreas illadas das montañas de Etiopía, por riba dos 3.000 msnm de altitude. Estas áreas reúnense en dous grupos maiores separados polo Gran Val do Rift, constituíndo dúas subespecies separadas: C.s. simensis ao noroeste e C.s. citernii ao sueste.

Polo seu aspecto lembra máis a un can doméstico primitivo como o dingo que ao típico lobo de Eurasia. Mide entre 90 e 100 centímetros de longo e entre 25 e 34 de altura sobre os ombreiros. O peso é de 11,5 kg nas femias e de 14 a 18,5 kg nos machos. O corpo é grácil, dotado de morro, orellas e patas longas. O pelame é avermellado-alaranxado en case todo o corpo, tornándose branco no interior das orellas, arredor dos ollos, boca, garganta, ventre, pés, cara interna das patas e da cola. Esta última é pouco longa e poboada, de cor negra desde a metade á punta e branca e vermella no resto.

O hábitat característico desta especie é o prado de tipo afro-alpino. Aliméntase case exclusivamente de roedores, destacando entre estes as ratas-toupa xigantes (Tachyoryctes macrocephalus), que constitúen preto do 40% dos alimentos que inxiren. Complementan a súa dieta con lebres e preas, aínda que en moi raras ocasións algúns individuos cooperan para dar morte a antílopes e pequenas cabras e ovellas domésticas. Salvando estas circunstancias excepcionais, os lobos etíopes pasan o día axexando roedores ou destruíndo os seus tobos para capturalos, sempre en solitario. Nas zonas onde sofren a persecución humana, estes animais abandonan os seus hábitos diúrnos e vólvense crepusculares ou nocturnos.

Os lobos etíopes viven en pequenos grupos, de marcada estrutura xerárquica, que se compoñen de dúas ou máis femias e uns cinco machos emparentados. Marcan o seu territorio (5-15 m²) con ouriños e feces e deféndeno dos intrusos. Existe unha parella dominante que se reproduce cada ano e á que os individuos subordinados axudan na cría da súa prole. En raras ocasións, as femias subordinadas tamén se reproducen.