pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

Wolbachia és un gènere de bacteris que infecten espècies d'artròpodes, incloent una alta proporció d'insectes (~60% de les espècies). És un dels microbis paràsits més comuns del món i possiblement el més comú de la biosfera entre els paràsits reproductius. Segons un estudi més del 16% de les espècies d'insectes neotropicals porten aquest bacteri.[1] i s'estima que entre el 25-70% de tots els insectes en poden ser potencialment hostes.[2]

Aquest bacteri va ser identificat, el 1924, per Marshall Hertig i S. Burt Wolbach en Culex pipiens, una espècie de mosquit.[3] El 1971 es descobrí que els ous d'aquest mosquit els matava Wolbachia per incompatibilitat citoplasmàtica.[4] És un bacteri molt interessant per la seva distribució ubiqua i les moltes interaccions evolutives.

Wolbachia és un gènere de bacteris que infecten espècies d'artròpodes, incloent una alta proporció d'insectes (~60% de les espècies). És un dels microbis paràsits més comuns del món i possiblement el més comú de la biosfera entre els paràsits reproductius. Segons un estudi més del 16% de les espècies d'insectes neotropicals porten aquest bacteri. i s'estima que entre el 25-70% de tots els insectes en poden ser potencialment hostes.

Aquest bacteri va ser identificat, el 1924, per Marshall Hertig i S. Burt Wolbach en Culex pipiens, una espècie de mosquit. El 1971 es descobrí que els ous d'aquest mosquit els matava Wolbachia per incompatibilitat citoplasmàtica. És un bacteri molt interessant per la seva distribució ubiqua i les moltes interaccions evolutives.

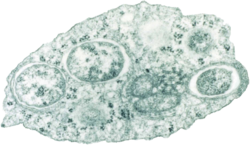

Wolbachia pipientis ist ein gramnegatives Bakterium und die einzige Art der Gattung Wolbachia innerhalb der Familie Ehrlichiaceae. Die pleomorphen Bakterien können als Bazillen von 0,5 bis 1,3 µm Länge, als Kokken von 0,25 bis 1,0 µm Durchmesser und als Riesenformen von 1 bis 1,8 µm Durchmesser auftreten. Das Bakterium hat sich in vitro und in vivo als empfindlich gegenüber Doxycyclin und Rifampicin erwiesen. Die Bakterien wachsen obligat in den Vakuolen der Zellen ihrer Wirte oder Symbionten und können nicht außerhalb dieser Umgebung kultiviert werden. Es gibt aber seit 1997 Zelllinien aus Eiern der Asiatischen Tigermücke (Aedes albopictus), mit und ohne Infektion mit Wolbachia pipientis.

Wolbachia pipientis ist erstmals in den Keimdrüsen der Gemeinen Stechmücke nachgewiesen worden. Bislang wurde das Bakterium in Insekten und anderen Gliederfüßern wie Krebstiere und Spinnentiere und in Filarien identifiziert. Dabei ist die Beziehung zwischen Wolbachia und ihren Wirten oder Symbionten vielgestaltig. Sie reicht von einer bei Arten von Drosophila beobachteten pathogenen Wirkung über Parasitismus und Mutualismus bis zur obligatorischen Symbiose. Wolbachia beeinflusst auf vielfältige Weise die Fortpflanzung der Wirte, wodurch insgesamt die weiblichen Tiere begünstigt und männlicher Nachwuchs im Embryonalstadium abgetötet oder phänotypisch feminisiert und so von der weiteren Reproduktion ausgeschlossen wird. Bei Insekten wird der Anteil infizierter Arten auf etwa 16 Prozent geschätzt.

Viele der betroffenen Wirte oder Symbionten sind Vektoren von Infektionskrankheiten. Zu ihnen gehören die Gelbfiebermücke, der Anopheles gambiae-Komplex und verschiedene Zecken. Unter den Filarien befinden sich bedeutende humanpathogene Parasiten wie Onchocerca volvulus, Wuchereria bancrofti und Brugia malayi. Wolbachia konnte nachgewiesen werden, dass sie die Erregerlast bei einigen Vektoren reguliert. Die Möglichkeit, die Reproduktion von Insektenvektoren durch das Aussetzen infizierter Männchen zu stören oder pathogene Filarien im Körper der erkrankten Tiere oder Menschen durch das Abtöten ihrer obligaten Symbionten Wolbachia zu bekämpfen ist Gegenstand jüngerer Forschungen.

Wolbachia pipientis ist ein gramnegatives und pleomorphes Bakterium. Die beschriebenen Formen sind Bazillen von 0,5 bis 1,3 µm Länge, Kokken von 0,25 bis 1,0 µm Durchmesser und Riesenformen von 1 bis 1,8 µm Durchmesser. Die Gattung Wolbachia unterscheidet sich von den Gattungen Anaplasma, Ehrlichia und Neorickettsia dadurch, dass sie keine Morulae bilden und nur Gliederfüßer und Filarien besiedeln. Sie unterscheidet sich von den Schwestertaxa auch durch ihre 16S rRNA, auf die sich heute die Systematik der Bakterien stützt.[1]

Von mehreren Stämmen von Wolbachia pipientis wurde bereits das Genom sequenziert. Der Stamm wMel (Supergruppe A, von Drosophila melanogaster) weist 1.267.782 Basenpaare und 1271 Protein-codierende Gene auf, während der Stamm wBm (Supergruppe D, von Brugia malayi) nur 1.080.084 Basenpaare und 806 Protein-codierende Gene hat. Ein gegenüber frei lebenden verwandten Arten verkleinertes Genom weisen auch Bakterien auf, die obligate Symbionten von Insekten sind. Beispiele sind Buchnera aphidicola, ein Symbiont der Erbsenlaus, Blochmannia sp. bei Rossameisen und Wigglesworthia glossinidia bei Tsetsefliegen. Das kleinere Genom der obligaten Symbionten bei Wolbachien wird als evolutionäre Anpassung verstanden. Demnach sind die bei parasitierenden Supergruppen noch vorhandenen Gene für Mechanismen des Eindringens in die Wirte und deren Manipulation als nutzlos verloren gegangen.[2][3][4]

Wolbachia lebt obligat in den Vakuolen der Zellen ihrer Wirte oder Symbionten, in denen sie sich durch Schizotomie vermehrt. In Gliederfüßern befinden sich die Wolbachien vorwiegend im Zytoplasma von Zellen der Geschlechtsorgane, aber auch von Nervenzellen und Blutkörperchen. Bei Filarien werden die Zellen der lateralen Nervenstränge und der weiblichen Fortpflanzungsorgane besiedelt. In allen Wirten erfolgt die vertikale Transmission von einer Generation zur nächsten, wobei männliche Wirte nur mittelbar oder gar nicht beteiligt sind.[1] Die große Verbreitung unter den Gliederfüßern und anderen Wirbellosen resultiert aus einer über lange Zeiträume immer wieder stattfindenden horizontalen Transmission zwischen den Wirten.[5]

Die Wirkungen von Wolbachia auf ihre Wirte werden jeweils als Strategien verstanden, die dem Bakterium eine hohe Übertragungsrate und eine weite Verbreitung sichert.[1]

Bei der Rollassel Armadillidium vulgare wird der Hormonhaushalt der Nachkommen gestört, so dass sich auch aus genotypisch männlichen Individuen phänotypische Weibchen entwickeln. Da zytoplasmische Merkmale, Mitochondrien und auch Wolbachien infizierter Tiere nur von Weibchen in die folgende Generation weitergegeben werden, ist mit der Feminisierung ein Vorteil für Wolbachia verbunden. Der Mechanismus besteht in der Unterdrückung der Entwicklung jener Drüsen, die männliche Sexualhormone produzieren. Die feminisierten genetischen Männchen stehen den nicht infizierten Männchen als Sexualpartner zur Verfügung, obwohl diese, wenn sie die Wahl haben, genetische Weibchen bevorzugen. Zudem ist die Feminisierung häufig unvollständig, die betroffenen Individuen weisen eine Mischung von männlichen und weiblichen Merkmalen auf. In feminisierten Populationen entsteht ein Mangel an männlichen Tieren, der teilweise durch größere sexuelle Aktivität der verbliebenen nicht infizierten Männchen kompensiert wird.[1][5]

Das einzige bislang bekannte Insekt, das eine feminisierende Wirkung von Wolbachien zeigt, ist der Tagfalter Eurema hecabe. Die Entfernung von Wolbachia durch die Gabe eines Antibiotikums führt dazu, dass die betroffenen Tiere nur noch männliche Nachkommen zeugen. Bei dem wirtschaftlich bedeutenden Pflanzenschädling Ostrinia scapulalis, einem Kleinschmetterling aus der Familie der Crambidae, wurde ebenfalls eine Feminisierung vermutet, tatsächlich wird die ausschließlich weibliche Nachkommenschaft infizierter Weibchen durch das Töten der männlichen Embryonen bewirkt.[5]

Da die vollständige Beseitigung fortpflanzungsfähiger genetischer Männchen in einer Population den Untergang sowohl des Wirtes, als auch seines Parasiten bewirken würde, gibt es eine Reihe von Mechanismen zum Erhalt der Arten. Bei der Mauerassel Oniscus asellus werden weniger als 88 Prozent der Nachkommen mit Wolbachia infiziert. Dadurch ist sichergestellt, dass sich in der folgenden Generation stets fortpflanzungsfähige Männchen befinden. Bei Insektenarten mit männlicher Heterogametie ist die Feminisierung mit einer hohen Sterblichkeit des Nachwuchses verbunden. Daher sind Gruppen wie die Hautflügler nicht von einer Feminisierung der Männchen betroffen.[5]

Eine weitere Strategie, weibliche Individuen als Überträger der Wolbachien zu begünstigen, besteht in der Parthenogenese. Weil sämtliche Nachkommen weiblich und Träger der Infektion sind, wird auch der Fortpflanzungserfolg des Bakteriums verdoppelt. Durch Wolbachien induzierte Parthenogenese wurde bislang in drei Ordnungen nachgewiesen, den Fransenflüglern (Thysanoptera) und Hautflüglern (Hymenoptera) bei den Insekten und den Trombidiformes bei den Spinnentieren. Damit konzentriert sich die Parthenogenese bei Wolbachia-infizierten Gliederfüßern auf Arten mit haplodiploider Geschlechtsdetermination.[5]

Unter den Rüsselkäfern wurde eine einzige parthenogenetische Art, Naupactus tesselatus, als Träger von Wolbachien identifiziert. Es ist jedoch noch nicht geklärt, ob das Bakterium bei der Entwicklung der Parthenogenese bei diesem und anderen parthenogenetischen Rüsselkäfern eine Rolle gespielt hat. Die bei einigen Arten der Gattung Drosophila nachgewiesenen Wolbachien scheinen nicht mit der Parthenogenese in Zusammenhang zu stehen. Wolbachien induzieren Parthenogenese auf unterschiedliche Weise. Es sind drei Wege beschrieben worden, zwei automiktische und ein apomiktische. Im Unterschied zu den Strategien der Feminisierung, des Male-Killing und der Zytoplasmischen Inkompabilität kann das Induzieren der Parthenogenese zum Erlöschen des männlichen Geschlechts führen. Es gibt aber auch Fälle, wie bei einigen Arten der Wespengattung Trichogramma, in denen infizierte und nicht infizierte Individuen koexistieren. Die infizierten unbefruchteten Weibchen vermehren sich parthenogenetisch und produzieren nur infizierte weibliche Nachkommen, während die nicht infizierten Weibchen unbefruchtet nicht infizierte weibliche Nachkommen und befruchtet nicht infizierte Männchen hervorbringen. Die Bevorzugung weiblicher Nachkommen kann Männchen selten werden lassen. Bei der Wespe Telenomus nawai (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) wurde eine Mutation festgestellt, die nicht infizierte Weibchen sowohl unbefruchtet als auch befruchtet in großer Zahl männlichen Nachwuchs produzieren lässt.[5]

Male Killing (MK) bezeichnet das Töten männlicher Nachkommen während der Embryogenese. Diese Strategie kann nur dann für die Wolbachien von Vorteil sein, wenn sie die infizierten Schwestern der absterbenden Männchen begünstigt. Das ist regelmäßig dort der Fall, wo Geschwister miteinander im Wettbewerb um knappe Ressourcen stehen. Man hat beobachtet, dass mit Wolbachia infizierte Weibchen des tropischen Schmetterlings Hypolimnas bolina ausschließlich weibliche Nachkommen hervorbringen. Zu den Insekten, bei denen die Infektion mit Wolbachien zum Tod der männlichen Nachkommen führt, gehört auch der Kleinschmetterling Ostrinia scapulalis. Während männliche Individuen als Larve absterben, sind weibliche Tiere zwingend auf Wolbachien angewiesen. Wenn das Bakterium mit Tetracyclin abgetötet wird, sterben auch die Weibchen. Im Experiment konnten infizierte Männchen durch die Mikroinjektion einer geringen Zahl von Wolbachien erzeugt werden. Auch die Tetracyclin-Behandlung von Weibchen kurz vor der Eiablage führte zur Entwicklung lebensfähiger infizierter männlicher Nachkommen, wenn sie in einem nicht tödlichen Ausmaß infiziert waren. Die Körper dieser Männchen wiesen eine Mischung männlicher und weiblicher Gewebe auf. Eine höhere Bakterienlast führte auch bei diesen Experimenten zum Absterben männlicher Larven.[5][6]

Weitere Insekten, in denen die Strategie des Male Killing verfolgt wird, sind die Taufliegen Drosophila bifasciata und Drosophila innublia, die Käfer Tribolium madens und Adalia bipunctata und der Schmetterling Acraea encedon. Auch der Pseudoskorpion Cordylochernes scorpioides gehört zu den betroffenen Arten.[5]

Die Zytoplasmische Inkompatibilität (CI) ist die am weitesten verbreitete Wirkung einer Infektion mit Wolbachien. Die Paarung eines infizierten Männchens mit einem Weibchen, das nicht oder mit einem anderen Stamm infiziert ist, führt zur gesteigerten Mortalität der Nachkommen. Im Extremfall sterben alle Nachkommen in der Embryonalphase ab. Durch diese Fehlpaarung werden die betroffenen Weibchen effektiv von der Fortpflanzung ausgeschlossen, nur die Überträgerinnen eines kompatiblen Bakterienstamms bringen mit infizierten Männchen lebensfähige infizierte Nachkommen hervor. Bezogen auf die Gesamtpopulation werden infizierte gegenüber nicht infizierten Weibchen im Fortpflanzungserfolg begünstigt.[1][7]

Der bezeichnete Effekt wurde nicht nur theoretisch vorhergesagt, sondern konnte in den 1980er Jahren bei der Ausbreitung von Wolbachien in einer ursprünglich nicht infizierten kalifornischen Population von Drosophila simulans beobachtet werden. Der genaue Wirkmechanismus ist noch unbekannt, die Spermien infizierter Männchen enthalten keine Wolbachien. Während der Spermatogenese müssen also die Spermien so manipuliert worden sein, dass sie bei der Befruchtung der Eier, abhängig vom Infektionsstatus des Weibchens, lebensfähige oder nicht lebensfähige Nachkommen zeugen.[5]

Die Zytoplasmische Inkompatibilität kann eine Reihe von phänotypischen Veränderungen bewirken, die auch bei Mutationen der Gene maternal haploid, ms(3)K81 und sésame der häufig in der Genetik als Modellorganismus genutzten Taufliege Drosophila melanogaster vorkommen. Auch bei der Untersuchung von Mutationen, die die Reproduktion beeinflussen, kann eine Infektion mit Wolbachien in entwicklungsbiologischen Laboren Untersuchungsergebnisse verfälschen. Ein großer Teil der in der Forschung genutzten Drosophila-Stämme ist mit Wolbachien infiziert.[5]

Die parasitoide Wespe Asobara tabida ist bei der Oogenese auf die Anwesenheit von Wolbachia pipientis angewiesen. Der Mechanismus ist noch nicht detailliert untersucht, aber die Behandlung mit Antibiotika zur Beseitigung der Wolbachien führt dazu, dass die Weibchen keine fruchtbaren Eier mehr produzieren. Damit wird der Ausschluss nicht infizierter Weibchen von der Fortpflanzung bewirkt. Asobara tabida ist stets mit Wolbachien dreier Stämme infiziert, wobei nur einer die oogenese beeinflusst und die beiden anderen zytoplasmische Inkompatibilität bewirkt.[8]

Wolbachia pipientis ist auf lebende Wirtszellen angewiesen und kann nicht alleine in einem Nährmedium am Leben erhalten werden. Es ist aber bereits 1997 gelungen, eine natürlich mit Wolbachia pipientis infizierte Zelllinie aus Eiern der Asiatischen Tigermücke (Aedes albopictus) zu kultivieren. Das Nährmedium war eine Mischung aus gleichen Teilen Mitsuhashi-Maramorosch-Insektenmedium und Schneiders Insektenmedium, dem 10 bis 15 Prozent Fetales Kälberserum zugefügt wurden. Dieser Wolbachia-Stamm wird auch nach dem Entwickler der Methode O’Neill-Stamm genannt und kann auch auf Kulturen von Fibroblasten aus humanem embryonalem Lungengewebe und auf einer anderen Zelllinie von Aedes albopictus in einem speziellen Nährmedium vermehrt werden.[1][9]

Eine Gruppe japanischer Molekulargenetiker entdeckte 2000 in Chromosomen verschiedener Stämme von Wolbachia genetisches Material des Bakteriophagen WO. Wie andere artspezifische Bakteriophagen spielt auch der Bakteriophage WO eine Rolle bei der Synthese eines mikrobiellen Toxins, indem er das genetische Material für die Toxinproduktion kodiert.[7]

Wolbachien infizieren eine große Bandbreite von Organismen. Dabei sind die Infektionen von Gliederfüßern meist parasitischer Natur, und die Infektionen von Nematoden eher symbiotischer Art. Wirbeltiere werden nicht infiziert.[5]

Die Schätzungen des Anteils der Insektenarten, die von Wolbachia pipientis infiziert werden, reichen von 16 bis 76 Prozent. Hinzu kommen zahlreiche weitere Arten von Gliederfüßern und Nematoden.[10] Die Verteilung innerhalb der taxonomischen Gruppen ist sehr unterschiedlich. Bei den Tierläusen scheinen Wolbachien fast alle Arten zu infizieren, während die als Vektoren zahlreicher Infektionskrankheiten bedeutenden Mücken der Gattung Anopheles frei von natürlichen Infektionen sind.[5]

Unter den Landasseln sind mehrere Arten mit Wolbachien der Supergruppe B infiziert, die eine Feminisierung männlicher infizierter Tiere bewirken.[5]

Einige humanpathogene Filarien wie Onchocerca volvulus, Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi und Brugia timori sind obligate Träger der endosymbiotisch lebenden Wolbachien. Eine veterinärmedizinisch bedeutende Art ist Dirofilaria immitis als Erreger der Herzwurmerkrankung des Hundes. Die Wolbachien werden mit den Eizellen in die jeweils nächste Generation weitergegeben und sind phylogenetischen Untersuchungen zufolge seit Millionen Jahren symbiotisch mit den Filarien verbunden. Die gemeinsame Evolution beider Arten und molekulargenetische Untersuchungen, die keine Hinweise auf Abwehrmechanismen gegen Wolbachia bei den Wirten und Reaktionen der Wolbachien darauf erkennen ließen, stützen die These der mutualistischen Beziehung.[11][2][12]

Die Verbreitung der Wolbachien bei den Filarien geht wahrscheinlich auf ein Infektionsereignis zurück, das die gemeinsamen Vorfahren der Unterfamilien Onchocercinae und Dirofilariinae betraf. Es ist noch ungeklärt, wie groß der Anteil von obligaten und fakultativen Trägern der Wolbachien unter den Arten der Filarien ist, und warum bei nahe verwandten Arten obligate Träger und Nicht-Träger vorkommen. Offenbar bietet Wolbachia den Trägern einen evolutionären Vorteil, der noch nicht identifiziert werden konnte. Bei einzelnen Arten ist die symbiotische Bindung an Wolbachia im Laufe der Evolution wieder verlorengegangen zu sein. Zu einem derartigen Verlust muss es in der Phylogenese der Onchocerciden mindestens sechs Mal gekommen sein.[2][13]

Die von diesen Filarien verursachten Erkrankungen des Menschen, die Onchozerkose der Haut und der Augen und die lymphatische Filariose mit der besonders schweren Form der Elephantiasis, gehören zu den schwersten und am weitesten verbreiteten Parasitosen. Die Erreger werden durch Mücken und Fliegen übertragen, die bei einer Blutmahlzeit von einem infizierten Wirt Mikrofilarien aufnehmen und sie bei den folgenden Wirten abgeben können. In den einer Neuinfektion folgenden zehn bis fünfzehn Jahren bei Onchocerca und fünf und mehr Jahren bei lymphatischer Filariose wachsen die Filarien im Wirt heran, vermehren sich millionenfach und können von Blutsaugern wieder aufgenommen und verbreitet werden. Zu Beginn des 21. Jahrhunderts waren weltweit 200 Millionen Menschen mit Filarien infiziert und mehr als eine Million Menschen exponiert.[11][14]

Bei Filarien infiziert Wolbachia die Zellen der lateralen Nervenstränge beider Geschlechter in allen Stadien, von den Mikrofilarien bis zum adulten Tier. Darüber hinaus werden die Geschlechtsorgane und die Eizellen der weiblichen Filarien und die Vorläufer der lateralen Nervenstränge in den Embryonalstadien infiziert, nicht jedoch die Geschlechtsorgane der männlichen Filarien. Vermutlich im Zusammenhang mit der Reproduktion kommt es in den Körpern der weiblichen Filarien kurz nach dem Befall eines Säugetierwirts zur Vervielfachung der Wolbachien. Da im Genom der Filarie Brugia malayi keine Gene identifiziert werden konnten, die bei anderen Tieren für die Produktion der Häme sorgen, wird den Wolbachien die Versorgung der Filarien mit Hämen zugeschrieben.[10][2]

Wolbachien tragen entscheidend zur Entwicklung, Fortpflanzung und pathogenen Wirkung der Filarien bei. Sie bewirken die Akkumulation und Aktivierung von neutrophilen Granulozyten um die Filarien und aktivieren Makrophagen. Die Neutrophilen sind wiederum am Abtöten und Abbauen der Mikrofilarien und am Entstehen der Onchozerkose als Ort der Kopulation geschlechtsreifer Onchocerca volvulus beteiligt. Im Mausmodell der Onchozerkose tragen Wolbachien und die von ihnen verursachte Reaktion der Neutrophilen entscheidend zur Keratitis als gravierendstem Symptom der Erkrankung bei, während die ebenfalls beteiligten eosinophilen Granulozyten durch die Anwesenheit der Mikrofilarien und die Makrophagen durch beide aktiviert werden.[11][15]

Der Verlust des Endosymbionten Wolbachia durch die Gabe von Antibiotika, Hitzeeinwirkung oder Entzug bestimmter Nährstoffe hat in Versuchen eine Vielzahl von Wirkungen auf den Wirt gezeigt: unvollständige Ausbildung abweichende Färbung des Exoskeletts, Kleinwüchsigkeit, Sterilität und Tod.[10]

Aedes aegypti und andere Mückenarten verlieren bei Infektion mit Wolbachia pipiens ihre Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit. Dies kann möglicherweise gezielt genutzt werden, indem man Wolbachia-infizierte männliche Mücken in großer Zahl in die Umwelt entlässt und der entstehende Nachwuchs aus gesunden weiblichen Tieren und infizierten männlichen Mücken nicht lebensfähig ist. Eine zweite Reproduktionsperiode erleben die Tiere nicht, so dass die Population dramatisch an Größe verliert. Die betroffenen Mückenarten sind Vektoren für verschiedene humanpathogene Arboviren, wie z. B. den Dengue-Virus[16][17] und den Malaria-Erreger Plasmodium.[18][19][20]

Die konventionelle Therapie der Filariosen besteht in der langfristigen Therapie mit filariziden Wirkstoffen wie Ivermectin, Albendazol und Diethylcarbamazin, meist in Kombination. Dabei werden die adulten Würmer nicht sicher abgetötet, so dass sich die Behandlung oft über mehrere Jahre bis zu ihrem natürlichen Tod erstrecken muss. Darüber hinaus führt die Therapie nach dem Absterben der Mikrofilarien zur Freisetzung von Wolbachien oder Lipopolysaccharid-ähnlichen Molekülen, die unerwünschte Immunreaktionen hervorrufen können.[21][22] Das Abtöten der Wolbachien durch den Einsatz von Antibiotika wie Doxycyclin könnte eine Möglichkeit der effektiven Bekämpfung der Filariosen sein. Der Verlust der Wolbachien führt zur langfristigen oder dauerhaften Sterilität der fortpflanzungsbereiten Filarien, so dass keine Fortpflanzung mehr stattfindet. Im Tierversuch wurde bei der Therapie der Rinder-Onchozerkose auch eine filarizide Wirkung beobachtet. Allerdings ist eine Therapie mit Doxycyclin bei Schwangeren, Stillenden und Kindern unter zehn Jahren kontraindiziert, so dass für diese Patienten weiter auf konventionelle Filarizide zurückgegriffen werden muss.[11][14]

Wolbachia wurde 1924 von den US-amerikanischen Mikrobiologen Marshall Hertig und Simeon Burt Wolbach entdeckt.[23] Die Erstbeschreibung erfolgte 1936 durch Hertig, wobei er die Gattung nach seinem Kollegen Wolbach benannte und das Artepithet an den wissenschaftlichen Namen des Typuswirts Culex pipiens anlehnte.[24][1]

Wolbachia wurde zunächst in die Tribus Wolbachieae der Familie Rickettsiaceae aufgenommen. Im Rahmen einer Revision der Ordnung Rickettsiales durch den US-amerikanischen Parasitologen Cornelius Becker Philip wurde sie 1956 mit den Gattungen Aegyptianella, Anaplasma, Ehrlichia und Neorickettsia in die Familie Anaplasmataceae gestellt. Diese Verwandtschaftsbeziehung wurde durch molekulargenetische Untersuchungen bestätigt.[1][25] Im Jahr 2020 erfolgte eine größere taxonomische Untersuchung der innerhalb der Alphaproteobacteria geführten taxonomischen Einteilung.[26] Hierbei wurde die Familie Anaplasmataceae aufgelöst und die Gattungen zu der wieder aufgestellten Familie Ehrlichiaceae gestellt.[27]

Wolbachia nimmt dabei eine Position zwischen den mit Würmern assoziierten Bakterien der Gattung Neorickettsia und den von Zecken übertragenen Anaplasma und Ehrlichia ein.[5]

In der zweiten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts wurden mehrere Arten der Gattung Wolbachia beschrieben, die mittlerweile in anderen Gattungen stehen oder lediglich Synonyme von Wolbachia pipientis sind:

Obgleich heute nur eine Art der Gattung Wolbachia anerkannt ist, wird innerhalb der Art eine hohe Diversität beobachtet. Diese Diversität wird nicht wie üblich in Form der Beschreibung weiterer Arten, sondern durch die Einteilung in Supergruppen zum Ausdruck gebracht.[2]

Aktuell werden bei Wolbachia pipientis 16 Supergruppen unterschieden, die mit den Buchstaben A bis Q bezeichnet werden und eine Klade bilden. Die Supergruppe G hat sich als eine Rekombination der Supergruppen A und B erwiesen.[33] Einer Beschreibung der von Höhlenspinnen der Gattung Telema isolierten Supergruppe R wurde 2016 widersprochen.[34][35] Ein Versuch, die Art Wolbachia pipientis in zahlreiche Arten aufzuspalten, wobei nur die Supergruppe B als Wolbachia pipientis erhalten bleiben sollte, stieß auf Ablehnung.[36][37][38]

Wolbachia pipientis wurde 1924 von den US-amerikanischen Entomologen Marshall Hertig und dem Pathologen Simeon Burt Wolbach entdeckt. Seinerzeit erforschten Hertig und Wolbach die Vektoren, die in den Vereinigten Staaten Rickettsien übertragen und Infektionskrankheiten wie Fleckfieber und Rocky-Mountain-Fleckfieber hervorrufen. Einer ihrer Funde war ein zunächst unbenannter Rickettsien-ähnlicher Mikroorganismus aus den Keimdrüsen der Gemeinen Stechmücke (Culex pipiens). erst 1936 veröffentlichte Hertig die Erstbeschreibung von Wolbachia pipientis.[23][24][10]

In den folgenden Jahrzehnten war Wolbachia ein weitgehend unbeachteter Mikroorganismus. In den 1960er und 1970er Jahren wurden von mehreren Forschern ungewöhnliche Strukturen in den Eizellen verschiedener Filarien beobachtet, die sie nicht identifizieren konnten. Erst 1995 wurden die Verursacher als Endosymbionten der Gattung Wolbachia erkannt. Mit den gesteigerten Bemühungen der Weltgesundheitsorganisation zur Beseitigung der Filariosen, die auch die Entschlüsselung der Genome humanpathogener Filarien einschlossen, kam es zu Funden bakterieller DNA, die zunächst als Kontamination der Proben gedeutet wurden. Auch sie waren durch Wolbachia pipientis verursacht.[10]

1973 wurden mit Armadillidium vulgare erstmals eine Landassel als Wirt von Wolbachia pipientis identifiziert. Weitere Arten folgten in den Jahren darauf. Die infizierten Asseln zeichnen sich dadurch aus, dass männliche Nachkommen infizierter Asseln feminisiert werden.[5]

1977 begann man zu verstehen, dass Wolbachien ihre Wirte in der Regel nicht parasitieren, sondern mit ihnen eine mutualistische Beziehung eingehen. Das wurde daraus gefolgert, dass insbesondere das Abtöten der Wolbachien in Filarien mit negativen Folgen für die Wirte bis hin zum Tod verbunden ist.[10]

2005 war das Genom von Wolbachia-Stämmen der Filarien entschlüsselt, so dass ein Vergleich mit dem Genom der Stämme von Arthropoden möglich wurde.[40]

Wolbachia pipientis ist ein gramnegatives Bakterium und die einzige Art der Gattung Wolbachia innerhalb der Familie Ehrlichiaceae. Die pleomorphen Bakterien können als Bazillen von 0,5 bis 1,3 µm Länge, als Kokken von 0,25 bis 1,0 µm Durchmesser und als Riesenformen von 1 bis 1,8 µm Durchmesser auftreten. Das Bakterium hat sich in vitro und in vivo als empfindlich gegenüber Doxycyclin und Rifampicin erwiesen. Die Bakterien wachsen obligat in den Vakuolen der Zellen ihrer Wirte oder Symbionten und können nicht außerhalb dieser Umgebung kultiviert werden. Es gibt aber seit 1997 Zelllinien aus Eiern der Asiatischen Tigermücke (Aedes albopictus), mit und ohne Infektion mit Wolbachia pipientis.

Wolbachia pipientis ist erstmals in den Keimdrüsen der Gemeinen Stechmücke nachgewiesen worden. Bislang wurde das Bakterium in Insekten und anderen Gliederfüßern wie Krebstiere und Spinnentiere und in Filarien identifiziert. Dabei ist die Beziehung zwischen Wolbachia und ihren Wirten oder Symbionten vielgestaltig. Sie reicht von einer bei Arten von Drosophila beobachteten pathogenen Wirkung über Parasitismus und Mutualismus bis zur obligatorischen Symbiose. Wolbachia beeinflusst auf vielfältige Weise die Fortpflanzung der Wirte, wodurch insgesamt die weiblichen Tiere begünstigt und männlicher Nachwuchs im Embryonalstadium abgetötet oder phänotypisch feminisiert und so von der weiteren Reproduktion ausgeschlossen wird. Bei Insekten wird der Anteil infizierter Arten auf etwa 16 Prozent geschätzt.

Viele der betroffenen Wirte oder Symbionten sind Vektoren von Infektionskrankheiten. Zu ihnen gehören die Gelbfiebermücke, der Anopheles gambiae-Komplex und verschiedene Zecken. Unter den Filarien befinden sich bedeutende humanpathogene Parasiten wie Onchocerca volvulus, Wuchereria bancrofti und Brugia malayi. Wolbachia konnte nachgewiesen werden, dass sie die Erregerlast bei einigen Vektoren reguliert. Die Möglichkeit, die Reproduktion von Insektenvektoren durch das Aussetzen infizierter Männchen zu stören oder pathogene Filarien im Körper der erkrankten Tiere oder Menschen durch das Abtöten ihrer obligaten Symbionten Wolbachia zu bekämpfen ist Gegenstand jüngerer Forschungen.

Wolbachia is a genus of intracellular bacteria that infects mainly arthropod species, including a high proportion of insects, and also some nematodes.[1][2] It is one of the most common parasitic microbes, and is possibly the most common reproductive parasite in the biosphere.[3] Its interactions with its hosts are often complex, and in some cases have evolved to be mutualistic rather than parasitic. Some host species cannot reproduce, or even survive, without Wolbachia colonisation. One study concluded that more than 16% of neotropical insect species carry bacteria of this genus,[4] and as many as 25 to 70% of all insect species are estimated to be potential hosts.[5]

The genus was first identified in 1924 by Marshall Hertig and Simeon Burt Wolbach in the common house mosquito. They described it as "a somewhat pleomorphic, rodlike, Gram-negative, intracellular organism [that] apparently infects only the ovaries and testes".[6] Hertig formally described the species in 1936, and proposed both the generic and specific names: Wolbachia pipientis.[7] Research on Wolbachia intensified after 1971, when Janice Yen and A. Ralph Barr of UCLA discovered that Culex mosquito eggs were killed by a cytoplasmic incompatibility when the sperm of Wolbachia-infected males fertilized infection-free eggs.[8][9] The genus Wolbachia is of considerable interest today due to its ubiquitous distribution, its many different evolutionary interactions, and its potential use as a biocontrol agent.

Phylogenetic studies have shown that Wolbachia persica (now Francisella persica) was closely related to species in the genus Francisella[10][11][12][13] and that Wolbachia melophagi (now Bartonella melophagi) was closely related to species in the genus Bartonella,[14][15][16] leading to a transfer of these species to these respective genera. Furthermore, unlike true Wolbachia, which needs a host cell to multiply, F. persica and B. melophagi can be cultured on agar plates.[17][16]

These bacteria can infect many different types of organs, but are most notable for the infections of the testes and ovaries of their hosts. Wolbachia species are ubiquitous in mature eggs, but not mature sperm. Only infected females, therefore, pass the infection on to their offspring. Wolbachia bacteria maximize their spread by significantly altering the reproductive capabilities of their hosts, with four different phenotypes:

Several host species, such as those within the genus Trichogramma, are so dependent on sexual differentiation of Wolbachia that they are unable to reproduce effectively without the bacteria in their bodies, and some might even be unable to survive uninfected.[25]

One study on infected woodlice showed the broods of infected organisms had a higher proportion of females than their uninfected counterparts.[26]

Wolbachia, especially Wolbachia-caused cytoplasmic incompatibility, may be important in promoting speciation.[27][28][29] Wolbachia strains that distort the sex ratio may alter their host's pattern of sexual selection in nature,[30][31] and also engender strong selection to prevent their action, leading to some of the fastest examples of natural selection in natural populations.[32]

The male killing and feminization effects of Wolbachia infections can also lead to speciation in their hosts. For example, populations of the pill woodlouse, Armadillidium vulgare which are exposed to the feminizing effects of Wolbachia, have been known to lose their female-determining chromosome.[33] In these cases, only the presence of Wolbachia can cause an individual to develop into a female.[33] Cryptic species of ground wētā (Hemiandrus maculifrons complex) are host to different lineages of Wolbachia which might explain their speciation without ecological or geographical separation.[34][35]

Wolbachia infection has been linked to viral resistance in Drosophila melanogaster, Drosophila simulans, and mosquito species. Flies, including mosquitoes,[36] infected with the bacteria are more resistant to RNA viruses such as Drosophila C virus, norovirus, flock house virus, cricket paralysis virus, chikungunya virus, and West Nile virus.[37][38][39]

In the common house mosquito, higher levels of Wolbachia were correlated with more insecticide resistance.[40]

In leafminers of the species Phyllonorycter blancardella, Wolbachia bacteria help their hosts produce green islands on yellowing tree leaves, that is, small areas of leaf remaining fresh, allowing the hosts to continue feeding while growing to their adult forms. Larvae treated with tetracycline, which kills Wolbachia, lose this ability and subsequently only 13% emerge successfully as adult moths.[41]

Muscidifurax uniraptor, a parasitoid wasp, also benefits from hosting Wolbachia bacteria.[42]

In the parasitic filarial nematode species responsible for elephantiasis, such as Brugia malayi and Wuchereria bancrofti, Wolbachia has become an obligate endosymbiont and provides the host with chemicals necessary for its reproduction and survival.[43] Elimination of the Wolbachia symbionts through antibiotic treatment therefore prevents reproduction of the nematode, and eventually results in its premature death.

Some Wolbachia species that infect arthropods also provide some metabolic provisioning to their hosts. In Drosophila melanogaster, Wolbachia is found to mediate iron metabolism under nutritional stress[44] and in Cimex lectularius, the Wolbachia strain cCle helps the host to synthesize B vitamins.[45]

Some Wolbachia strains have increased their prevalence by increasing their hosts' fecundity. Wolbachia strains captured from 1988 in southern California still induce a fecundity deficit, but nowadays the fecundity deficit is replaced with a fecundity advantage such that infected Drosophila simulans produces more offspring than the uninfected ones.[46]

Wolbachia often manipulates host reproduction and life-history in a way that favours its own propagation. In the Pharaoh ant, Wolbachia infection correlates with increased colony-level production of reproductives (i.e., greater reproductive investment), and earlier onset of reproductive production (i.e., shorter life-cycle). Infected colonies also seem to grow more rapidly.[47] There is substantial evidence that the presence of Wolbachia that induce parthenogenesis have put pressure on species to reproduce primarily or entirely this way.[48]

Additionally, Wolbachia has been seen to decrease the lifespan of Aedes aegypti, carriers of mosquito-borne diseases, and it decreases their efficacy of pathogen transmission because older mosquitoes are more likely to have become carriers of one of those diseases.[49] This has been exploited as a method for pest control.

The first Wolbachia genome to be determined was that of one that infects D. melanogaster fruit flies.[50] This genome was sequenced at The Institute for Genomic Research in a collaboration between Jonathan Eisen and Scott O'Neill. The second Wolbachia genome to be determined was one that infects Brugia malayi nematodes.[51] Genome sequencing projects for several other Wolbachia strains are in progress. A nearly complete copy of the Wolbachia genome sequence was found within the genome sequence of the fruit fly Drosophila ananassae and large segments were found in seven other Drosophila species.[52]

In an application of DNA barcoding to the identification of species of Protocalliphora flies, several distinct morphospecies had identical cytochrome c oxidase I gene sequences, most likely through horizontal gene transfer (HGT) by Wolbachia species as they jump across host species.[53] As a result, Wolbachia can cause misleading results in molecular cladistical analyses.[54] It is estimated that between 20 and 50 percent of insect species have evidence of HGT from Wolbachia—passing from microbes to animal (i.e. insects).[55]

Wolbachia species also harbor a bacteriophage called bacteriophage WO or phage WO.[56] Comparative sequence analyses of bacteriophage WO offer some of the most compelling examples of large-scale horizontal gene transfer between Wolbachia coinfections in the same host.[57] It is the first bacteriophage implicated in frequent lateral transfer between the genomes of bacterial endosymbionts. Gene transfer by bacteriophages could drive significant evolutionary change in the genomes of intracellular bacteria that were previously considered highly stable or prone to loss of genes over time.[57]

The small non-coding RNAs WsnRNA-46 and WsnRNA-59 in Wolbachia were detected in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and Drosophila melanogaster. The small RNAs (sRNAs) may regulate bacterial and host genes.[58] Highly conserved intragenic region sRNA called ncrwmel02 was also identified in Wolbachia pipientis. It is expressed in four different strains in a regulated pattern that differs according to the sex of the host and the tissue localisation. This suggested that the sRNA may play important roles in the biology of Wolbachia.[59]

Outside of insects, Wolbachia infects a variety of isopod species, spiders, mites, and many species of filarial nematodes (a type of parasitic worm), including those causing onchocerciasis (river blindness) and elephantiasis in humans, as well as heartworms in dogs. Not only are these disease-causing filarial worms infected with Wolbachia, but Wolbachia also seems to play an inordinate role in these diseases.

A large part of the pathogenicity of filarial nematodes is due to host immune response toward their Wolbachia. Elimination of Wolbachia from filarial nematodes generally results in either death or sterility of the nematode.[60] Consequently, current strategies for control of filarial nematode diseases include elimination of their symbiotic Wolbachia via the simple doxycycline antibiotic, rather than directly killing the nematode with often more toxic antinematode medications.[61]

Naturally existing strains of Wolbachia have been shown to be a route for vector control strategies because of their presence in arthropod populations, such as mosquitoes.[62][63] Due to the unique traits of Wolbachia that cause cytoplasmic incompatibility, some strains are useful to humans as a promoter of genetic drive within an insect population. Wolbachia-infected females are able to produce offspring with uninfected and infected males; however, uninfected females are only able to produce viable offspring with uninfected males. This gives infected females a reproductive advantage that is greater the higher the frequency of Wolbachia in the population. Computational models predict that introducing Wolbachia strains into natural populations will reduce pathogen transmission and reduce overall disease burden.[64] An example includes a life-shortening Wolbachia that can be used to control dengue virus and malaria by eliminating the older insects that contain more parasites. Promoting the survival and reproduction of younger insects lessens selection pressure for evolution of resistance.[65][66]

In addition, some Wolbachia strains are able to directly reduce viral replication inside the insect. For dengue they include wAllbB and wMelPop with Aedes aegypti, wMel with Aedes albopictus.[67] and Aedes aegypti.[68] A trial in an Australian city with 187,000 inhabitants plagued by dengue had no cases in four years, following introduction of mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia. Earlier trials in much smaller areas had been carried out, but the effect in a larger area had not been tested. There did not appear to be any environmental ill-effects. The cost was A$15 per inhabitant, but it was hoped that it could be reduced to US$1 in poorer countries with lower labor costs.[69] The "strongest evidence yet" to support the Wolbachia technique was found in its first randomized controlled trial, conducted between 2016 and 2020 in Yogyakarta, an Indonesian city of about 400,000 inhabitants. In August 2020, the trial's Indonesian lead scientist Adi Utarini announced that the trial showed a 77% reduction in dengue cases compared to the control areas.[70][71]

Wolbachia has also been identified to inhibit replication of chikungunya virus (CHIKV) in A. aegypti. The wMel strain of Wolbachia pipientis significantly reduced infection and dissemination rates of CHIKV in mosquitoes, compared to Wolbachia uninfected controls and the same phenomenon was observed in yellow fever virus infection converting this bacterium in an excellent promise for YFV and CHIKV suppression.[72]

Wolbachia also inhibits the secretion of West Nile virus (WNV) in cell line Aag2 derived from A. aegypti cells. The mechanism is somewhat novel, as the bacteria actually enhances the production of viral genomic RNA in the cell line Wolbachia. Also, the antiviral effect in intrathoracically infected mosquitoes depends on the strain of Wolbachia, and the replication of the virus in orally fed mosquitoes was completely inhibited in wMelPop strain of Wolbachia.[73]

The effect of Wolbachia infection on virus replication in insect hosts is complex and depends on the Wolbachia strain and virus species.[74] While several studies have indicated consistent refractory phenotypes of Wolbachia infection on positive-sense RNA viruses in Drosophila melanogaster,[75][76] the yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti[77] and the Asian tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus.[78][79] This effect is not seen in DNA virus infection[76] and in some cases Wolbachia infection has been associated or shown to increase single stranded DNA[80] and double-stranded DNA virus infection.[81] There is also currently no evidence that Wolbachia infection restricts any tested negative-sense RNA viruses[82][83][84][85] indicating Wolbachia would be unsuitable for restriction of negative-sense RNA arthropod borne viruses.

Wolbachia infection can also increase mosquito resistance to malaria, as shown in Anopheles stephensi where the wAlbB strain of Wolbachia hindered the lifecycle of Plasmodium falciparum.[86]

However, Wolbachia infections can enhance pathogen transmission. Wolbachia has enhanced multiple arboviruses in Culex tarsalis mosquitoes.[87] In another study, West Nile Virus (WNV) infection rate was significantly higher in Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes compared to controls.[88]

Wolbachia may induce reactive oxygen species–dependent activation of the Toll (gene family) pathway, which is essential for activation of antimicrobial peptides, defensins, and cecropins that help to inhibit virus proliferation.[89] Conversely, certain strains actually dampen the pathway, leading to higher replication of viruses. One example is with strain wAlbB in Culex tarsalis, where infected mosquitoes actually carried the west nile virus (WNV) more frequently. This is because wAlbB inhibits REL1, an activator of the antiviral Toll immune pathway. As a result, careful studies of the Wolbachia strain and ecological consequences must be done before releasing artificially-infected mosquitoes in the environment.[90]

In 2016 it was proposed to combat the spread of the Zika virus by breeding and releasing mosquitoes that have intentionally been infected with an appropriate strain of Wolbachia.[91] A contemporary study has shown that Wolbachia has the ability to block the spread of Zika virus in mosquitoes in Brazil.[92]

In October 2016, it was announced that US$18 million in funding was being allocated for the use of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes to fight Zika and dengue viruses. Deployment is slated for early 2017 in Colombia and Brazil.[93]

In July 2017, Verily, the life sciences arm of Google's parent company Alphabet Inc., announced a plan to release about 20 million Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in Fresno, California, in an attempt to combat the Zika virus.[94][95] Singapore's National Environment Agency has teamed up with Verily to come up with an advanced, more efficient way to release male Wolbachia mosquitoes for Phase 2 of its study to suppress the urban Aedes aegypti mosquito population and fight dengue.[96]

On November 3, 2017, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) registered Mosquito Mate, Inc. to release Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes in 20 US states and the District of Columbia.[97]

The enzyme aromatase is found to mediate sex-change in many species of fish. Wolbachia can affect the activity of aromatase in developing fish embryos.[98]

Wolbachia is a genus of intracellular bacteria that infects mainly arthropod species, including a high proportion of insects, and also some nematodes. It is one of the most common parasitic microbes, and is possibly the most common reproductive parasite in the biosphere. Its interactions with its hosts are often complex, and in some cases have evolved to be mutualistic rather than parasitic. Some host species cannot reproduce, or even survive, without Wolbachia colonisation. One study concluded that more than 16% of neotropical insect species carry bacteria of this genus, and as many as 25 to 70% of all insect species are estimated to be potential hosts.

Wolbachia aŭ Volbaĥio estas genro de bakterioj, kiuj parazitas krabojn, ĥeliceruloj (Chelicera), kaj precipe la insektojn, sed ankaŭ kelkajn fadenvermojn. Laŭ kalkuloj, ĉ. 18-30% de la insektoj estas infektita. La infektado de Wolbachia okazas tra la ovoĉelo en la mastrobesto.

La volbaĥio-specioj povas transformi la bestojn konvene al siaj bezonoj, ili kapablas do ekz.:

Pro la supre menciitaj, la volbaĥio-specioj baze influas la populacio-dinamikon de la insektoj kaj eĉ do influas ties evoluon.

Volbaĥia infektado okazas ankaŭ en la fadenvermoj, inter alie en la specioj de la afrika Onchocerca, kiuj estas la plej gravaj infektaj bestoj de la homo kaj bovo en la tropika Afriko. Tion oni povas trakti per uzo de antibiotikoj, ĉar la rilato inter la bakterio kaj vermo estas simbioza.

Laŭ sciencaj publikaĵoj de 2007, la volbaĥio eĉ transdonas genojn al la insektoj (oni trovis tutan genomon en la Drosophila ananassae, laŭ Science).

Wolbachia aŭ Volbaĥio estas genro de bakterioj, kiuj parazitas krabojn, ĥeliceruloj (Chelicera), kaj precipe la insektojn, sed ankaŭ kelkajn fadenvermojn. Laŭ kalkuloj, ĉ. 18-30% de la insektoj estas infektita. La infektado de Wolbachia okazas tra la ovoĉelo en la mastrobesto.

La volbaĥio-specioj povas transformi la bestojn konvene al siaj bezonoj, ili kapablas do ekz.:

femaligi la infektitajn masklajn mastrobestojn malhelpi, ke la infektita femalo demetu masklajn idojn, detrui la masklajn embriojn, devigi je partenogenezo malfekundigi infektitan masklonPro la supre menciitaj, la volbaĥio-specioj baze influas la populacio-dinamikon de la insektoj kaj eĉ do influas ties evoluon.

Volbaĥia infektado okazas ankaŭ en la fadenvermoj, inter alie en la specioj de la afrika Onchocerca, kiuj estas la plej gravaj infektaj bestoj de la homo kaj bovo en la tropika Afriko. Tion oni povas trakti per uzo de antibiotikoj, ĉar la rilato inter la bakterio kaj vermo estas simbioza.

Laŭ sciencaj publikaĵoj de 2007, la volbaĥio eĉ transdonas genojn al la insektoj (oni trovis tutan genomon en la Drosophila ananassae, laŭ Science).

Wolbachia es un género de bacterias gram negativas que infecta especies de artrópodos, en particular a una alta proporción de insectos, y también algunos nemátodos. Es uno de los microbios parásitos más comunes y es posiblemente el parásito reproductivo más común en la biosfera. Las interacciones con sus anfitriones son a menudo complejas, y en algunos casos han evolucionado para ser mutualistas en lugar de parasitarias. Algunas especies no pueden reproducirse, o incluso sobrevivir, sin ser colonizadas por la bacteria. Un estudio concluyó que más del 16% de las especies de insectos tropicales portan bacterias de este género y se estima que entre el 25 y el 70% de todas las especies de insectos son potenciales portadoras.[1]

La eliminación de Wolbachia de los nemátodos del filariasis generalmente los mata o los hace estériles.

Dentro de los artrópodos, Wolbachia es notable por el hecho que altera significativamente las capacidades reproductoras de sus hospedadores. Estas bacterias pueden infectar diferentes tipos de órganos, pero es muy notable en las infecciones de los testículos y ovarios de los mismos.

Se conocen Wolbachia para causar cuatro fenotipos diferentes:

Wolbachia está presente en los huevos maduros, pero no en el esperma maduro. Se infectan sólo hembras que pasan la infección en adelante a su descendencia. Se piensa que los fenotipos causados por Wolbachia, sobre todo la incompatibilidad citoplasmática, ha sido importante promoviendo la especiación. Un concepto central de las teorías de especiación es el de aislamiento reproductivo: los genes de dos poblaciones aisladas reproductivamente pueden divergir hasta alcanzar la incompatibilidad genética. En este punto, se considera que a partir de la especie original han surgido dos especies.

Según Werren, Wolbachia puede constituir un mecanismo idóneo para generar aislamiento reproductivo. Werren y sus colaboradores han observado que en una especie de insecto, tal aislamiento puede originarse entre dos poblaciones infectadas por distintas cepas de Wolbachia. Werren sugiere que el mapeo génico de la diversidad de insectos infectados y no infectados podría aportar pruebas a favor de esta teoría.

La bacteria se identificó primero en 1924 por Hertig y Wolbach en Culex pipiens, una especie de mosquito (Hertig y Wolbach, 1924). Finalmente, en 1971, Janice Yen y Ralph Barr (Universidad de California) establecieron que una bacteria del género Wolbachia es la culpable del fenómeno hoy conocido como incompatibilidad citoplasmática.

Más del 16% de especies de insectos de Panamá presentan esta bacteria.[cita requerida]

Cepas naturales de Wolbachia han demostrado ser un medio para las estrategias de control de vectores debido a su presencia en poblaciones de mosquitos.[2][3] Debido a los rasgos únicos de Wolbachia que causan incompatibilidad citoplasmática, algunas cepas son útiles como promotores de un direccionamiento genético dentro de una población de insectos. Las hembras infectadas con Wolbachia pueden producir descendencia con machos no infectados e infectados; sin embargo, las hembras no infectadas solo pueden producir descendencia viable con machos no infectados. Esto le da a las hembras infectadas una ventaja reproductiva que es mayor cuanto mayor es la frecuencia de Wolbachia en la población. Los modelos computacionales predicen que la introducción de cepas de Wolbachia en poblaciones naturales reducirá la transmisión de patógenos y reducirá la carga general de la enfermedad.[4] Un ejemplo incluye una cepa de Wolbachia que acorta la vida del mosquito y que puede usarse para controlar el virus del dengue mediante la eliminación de los insectos más viejos que contienen más parásitos.[5][6][7]

Además, algunas cepas de Wolbachia pueden reducir directamente la replicación viral dentro del insecto. Para el dengue, incluyen wAllbB y wMelPop con Aedes aegypti, y wMel con Aedes albopictus[8] y Aedes aegypti.[9] Un ensayo en una ciudad australiana de 187,000 habitantes plagada de dengue, no tuvo casos en cuatro años luego de la introducción de mosquitos infectados con Wolbachia. Se habían llevado a cabo ensayos anteriores en áreas mucho más pequeñas, pero no se había probado el efecto en un área de este tamaño. No se presentaron efectos ambientales negativos. El costo fue de A $ 15 por habitante, pero se esperaba que pudiera reducirse a US $ 1 en los países más pobres.[10] En junio de 2021 se informaron resultados alentadores en una prueba controlada aleatorizada realizada en la ciudad de Yogyakarta.[11]

Wolbachia es un género de bacterias gram negativas que infecta especies de artrópodos, en particular a una alta proporción de insectos, y también algunos nemátodos. Es uno de los microbios parásitos más comunes y es posiblemente el parásito reproductivo más común en la biosfera. Las interacciones con sus anfitriones son a menudo complejas, y en algunos casos han evolucionado para ser mutualistas en lugar de parasitarias. Algunas especies no pueden reproducirse, o incluso sobrevivir, sin ser colonizadas por la bacteria. Un estudio concluyó que más del 16% de las especies de insectos tropicales portan bacterias de este género y se estima que entre el 25 y el 70% de todas las especies de insectos son potenciales portadoras.

La eliminación de Wolbachia de los nemátodos del filariasis generalmente los mata o los hace estériles.

Wolbachia generoa bakterio Gram negatiboz osatuta dago, zelula barneko parasito hertsiak direnak. Intsektu eta beste artropodo batzuk infektatzen ditu, eta baita hainbat nematodo ere. Hainbat ikerketak intsektu guztien %25-%70aren artean bakterio honekin infektatuta egon litezkeela planteatzen dute [1]. Naturan oso hedatuta dagoen bakterio parasitoa da, beraz.

1924an bakterio hau lehenbizikoz identifikatu zuten S. Wolbach eta M. Hertig mikrobiologek eltxo baten gonadetan.

Zelula barneko parasito hertsia izanik, zaila da laborategian Wolbachia kultibatzea [2]

Intsektu eta artropodoen gonadak (obarioak eta barrabilak) infektatzen ditu Wolbachiak. Emeen kasuan, bakterio parasitoak obuluak infektatzen ditu, eta modu horretan bakterioaren transmisio bertikala gauzatzen da: Wolbachiak intsektu amarengandik ondorengo guztiengana pasatuko du.

Bakterioaren transmisioan, horrenbestez, emeek funtsezko zeregina burutzen dute. Ez da gauza bera gertatzen arrekin, inongo zerikusirik ez dutenak prozesu horretan (emeak estali izan ezik). Wolbachiak estrategia bereziak garatu ditu bere transmisioa ziurtatzeko: esaterako, eltxo ar infektatuek eme ez-infektatuak estaltzen badituzte ez da ondorengorik sortuko; baina ar infektatuek edo ez-infektatuek eme infektatuak estaltzen dituztenean ondorengoak agertuko dira inongo arazorik gabe [3]

Intsektu batzuetan egiaztatu da Wolbachiak partenogenesia eragiten duela eta baita arren feminizazioa ere (sexu-aldaketa, arrak emeak bihurtzen baitira) [4]. Bi prozesu hauen bitartez bakterioak bere biziraupena bermatzen du.

Gaixotasun infekzioso batzuen prebentzioan Wolbachia aliatu interesgarria izan liteke.

Esaterako, Wolbachiak filaria batzuk infektatzen ditu, gaitz larriak sortzen dituzten filariak (filariasiak). Nematodoen infekzioa ez da parasitarioa, sinbiotikoa baizik: bakterioak bitamina eta beste substantzia batzuk ematen dizkio harrari. Horregatik, Wolbachia gabe nematodoak ezin du bizi [5]. Menpekotasun hori kontuan hartuta, filariasien prebentzioan eta terapian Wolbachia hiltzen duten botikak erabiltzen dira. Horrek nematodoen desagerpena dakar eta baita filariasiaren hobekuntza, gaitz horietan agertzen den erantzun immunitario bortitza, antza, Wolbachiak eragiten duelako [6]

Filariasia ez ezik, dengea eta malaria prebenitzeko ere Wolbachiak laguntza handia ematen du. Gauza jakina da Aedes aegypti eltxoak ezin duela dengea transmititu Wolbachiaz infektatuta baldin badago. Horren zergatia ezezaguna da oraindik (dengearen birusa hilko du Wolbachiak?), baina aurkikuntzak potentzialitate handia dauka dengearen prebentzioan, eltxoak Wolbachiaz infektatuz. Beste hainbeste gertatzen da malaria transmititzen duten eltxoekin: Wolbachiaren infekzioak eltxoak malariaren eragilearekiko (Plasmodium falciparum) duten erresistentzia areagotzen du, antza [7]. Ikerketa ugari egiten ari dira arlo itxaropentsu horretan. Eltxoen aurkako intsektizidak erabili beharrean, dengea eta malaria prebenitzeko wolbachiaren erabilpena askoz eraginkorragoa izan liteke.

Wolbachia generoa bakterio Gram negatiboz osatuta dago, zelula barneko parasito hertsiak direnak. Intsektu eta beste artropodo batzuk infektatzen ditu, eta baita hainbat nematodo ere. Hainbat ikerketak intsektu guztien %25-%70aren artean bakterio honekin infektatuta egon litezkeela planteatzen dute . Naturan oso hedatuta dagoen bakterio parasitoa da, beraz.

1924an bakterio hau lehenbizikoz identifikatu zuten S. Wolbach eta M. Hertig mikrobiologek eltxo baten gonadetan.

Zelula barneko parasito hertsia izanik, zaila da laborategian Wolbachia kultibatzea

Intsektu eta artropodoen gonadak (obarioak eta barrabilak) infektatzen ditu Wolbachiak. Emeen kasuan, bakterio parasitoak obuluak infektatzen ditu, eta modu horretan bakterioaren transmisio bertikala gauzatzen da: Wolbachiak intsektu amarengandik ondorengo guztiengana pasatuko du.

Bakterioaren transmisioan, horrenbestez, emeek funtsezko zeregina burutzen dute. Ez da gauza bera gertatzen arrekin, inongo zerikusirik ez dutenak prozesu horretan (emeak estali izan ezik). Wolbachiak estrategia bereziak garatu ditu bere transmisioa ziurtatzeko: esaterako, eltxo ar infektatuek eme ez-infektatuak estaltzen badituzte ez da ondorengorik sortuko; baina ar infektatuek edo ez-infektatuek eme infektatuak estaltzen dituztenean ondorengoak agertuko dira inongo arazorik gabe

Intsektu batzuetan egiaztatu da Wolbachiak partenogenesia eragiten duela eta baita arren feminizazioa ere (sexu-aldaketa, arrak emeak bihurtzen baitira) . Bi prozesu hauen bitartez bakterioak bere biziraupena bermatzen du.

Wolbachia on Gram-negatiivisiin bakteereihin kuuluva obligaatti endosymbiontti, joka infektoi lukuisia niveljalkaisia ja sukkulamatoja.[1] Wolbachia-infektiot ovat luonnossa yleisiä, arvioiden mukaan jopa 40% maailman niveljalkaisista ja yli 65% kaikista hyönteislajeista ovat alttiita Wolbachia-infektiolle.[2] Wolbachia-infektio tapahtuu ensisijaisesti äidiltä jälkeläisille eli vertikaalisesti, mutta myös lajista-lajiin- ja ympäristöstä yksilöön- infektioita tapahtuu (ns. horisontaalinen infektio). Wolbachia-bakteerin suhde isäntähyönteisen kanssa riippuu lajista. Usein Wolbachian suhde isäntään on mutualistinen: bakteerin on tutkittu suojaavan isäntähyönteistä virusinfektioilta, tuottavan isännälle ravintoaineita ja sukkulamadoissa lisäävän isännän elinikää ja hedelmällisyyttä.[3] Niveljalkaisissa Wolbachia voi olla myös parasiitti. Wolbachian tiedetään niveljalkaisissa isäntähyönteisissä muuttavan merkittävästi isännän lisääntymisbiologiaa ja suuntaavan sukupuolivalintaa.[4]

Filariaparasiitit, kuten Burgia malayi, ovat yleisiä trooppisilla alueilla ja aiheuttavat vakavasti vammauttavia sairauksia (esimerkiksi elefanttitauti ja jokisokeus).[5] Wolbahcia-bakteeria esiintyy lähes kaikissa ihmislajia infektoivissa filariaparasiitteissa mutualistisena endosymbionttina. Wolbachia lisää filariamadon elinikää ja hedelmällisyyttä sekä osallistuu sikiönkehityksen ohjaamiseen. Wolbachia voidaan poistaa filariamadosta antibiooteilla. Ilman bakteeria filariamadon elinaika lyhenee kymmenistä vuosista muutamiin kuukausiin ja jälkeläisten kehityksessä esiintyy normaalia useammin häiriöitä.[6]

Wolbachia on Gram-negatiivisiin bakteereihin kuuluva obligaatti endosymbiontti, joka infektoi lukuisia niveljalkaisia ja sukkulamatoja. Wolbachia-infektiot ovat luonnossa yleisiä, arvioiden mukaan jopa 40% maailman niveljalkaisista ja yli 65% kaikista hyönteislajeista ovat alttiita Wolbachia-infektiolle. Wolbachia-infektio tapahtuu ensisijaisesti äidiltä jälkeläisille eli vertikaalisesti, mutta myös lajista-lajiin- ja ympäristöstä yksilöön- infektioita tapahtuu (ns. horisontaalinen infektio). Wolbachia-bakteerin suhde isäntähyönteisen kanssa riippuu lajista. Usein Wolbachian suhde isäntään on mutualistinen: bakteerin on tutkittu suojaavan isäntähyönteistä virusinfektioilta, tuottavan isännälle ravintoaineita ja sukkulamadoissa lisäävän isännän elinikää ja hedelmällisyyttä. Niveljalkaisissa Wolbachia voi olla myös parasiitti. Wolbachian tiedetään niveljalkaisissa isäntähyönteisissä muuttavan merkittävästi isännän lisääntymisbiologiaa ja suuntaavan sukupuolivalintaa.

Wolbachia est un genre de bactéries qui infectent essentiellement des arthropodes, environ 60 % des espèces[1], ainsi que certaines espèces de nématodes[2]. Cette large répartition en fait donc un des symbiotes les plus répandus du monde animal. Ces bactéries au mode de vie intracellulaire sont localisées au sein du cytoplasme des cellules de leurs hôtes. Elles se retrouvent en proportion importante dans l'appareil reproducteur (principalement les cellules germinales) et l’épithélium du système génital des arthropodes et nématodes.

Leur nom vient de Simeon Burt Wolbach (en) (1880-1954).

Wolbachia pipientis a été divisée en super-groupes nommés par des lettres: Les clades A, B, E, H infectent des arthropodes, les clades C, D, J attaquent des nématodes filaires, le clade S parasite des pseudoscorpions, le clade E des collemboles et le clade F infecte à la fois des arthropodes et des nématodes filaires[3],[4]. D'autres clades infectent des groupes d'arthropodes plus restreints, tel que le clade M qui infecte uniquement des pucerons, le groupe H qui parasite des termites ou le groupe I qui s'attaque aux puces[3].

La transmission de Wolbachia est essentiellement verticale : elles sont transmises de mère à descendants via le cytoplasme des ovocytes. Le spermatozoïde ne transmettant que son noyau lors de la fécondation, les mâles sont incapables de transmettre les bactéries à leur descendance. C'est pour cette raison que Wolbachia a pour particularité de manipuler la reproduction de leurs hôtes : la valeur sélective des femelles infectées est augmentée par différents effets, ce qui maximise la probabilité de transmission de Wolbachia.

Wolbachia pourrait également, dans certaines conditions, se transmettre de manière horizontale, d’une espèce à une autre. Par exemple, des drosophiles infectées par Wolbachia pourraient transmettre le parasite aux larves de la guêpe parasitoïde Nasonia vitripennis. Celle-ci dépose ses œufs dans une pupe de mouche, et la larve se contaminerait à l’intérieur de la mouche. Chez les crustacés isopodes terrestres, des études ont montré que les transferts horizontaux de Wolbachia peuvent s'effectuer par contacts infectieux. Via une blessure, l'hémolymphe d'un individu infecté peut être vecteur de Wolbachia et entraîner la contamination d'un individu auparavant sain[5].

Wolbachia est connu pour 4 effets principaux de manipulations de la reproduction.

Le plus connu : l'incompatibilité cytoplasmique a été définie en 1952 par Ghelelovitch chez le moustique commun, Culex pipiens. Elle se caractérise dans sa forme la plus simple par une réduction totale ou partielle du nombre de descendants viables lors du croisement entre un mâle infecté et une femelle non infectée. C’est l’incompatibilité cytoplasmique unidirectionnelle. Cet effet tend à diminuer la capacité de reproduction des femelles non-infectées, ce qui permet l’invasion des populations. L’incompatibilité cytoplasmique bidirectionnelle se caractérise par deux souches distinctes de Wolbachia qui vont être incompatibles entre elles, lorsqu’elles sont présentes dans des individus différents[6]. Cela va diminuer la capacité de reproduction des femelles se reproduisant avec un mâle infecté par une autre souche.

Selon les espèces qu’elle infecte, la présence de Wolbachia peut entraîner la dégénérescence des embryons mâles (par exemple chez certaines espèces de coccinelles), les féminiser en transformant les mâles génétiques en femelles fonctionnelles (par exemple chez le cloporte Armadillidium vulgare).

Chez les hyménoptères à développement haplodiploïde, la présence de Wolbachia entraîne une parthénogenèse thélytoque. En l'absence de Wolbachia, les œufs, issus d'oocytes fécondés, diploïdes, se développent en femelles tandis que les oocytes non fécondés, haploïdes, donnent des individus mâles. Chez les individus infectés, Wolbachia entraîne une diploïdisation du matériel génétique des oocytes non fécondés : la stratégie de Wolbachia est d’augmenter le nombre de femelles infectées car les mâles ne transmettent pas le parasite.

En rendant certains croisements stériles et en limitant ainsi le brassage génétique de ses hôtes, la bactérie Wolbachia pourrait participer à des phénomènes de spéciation (apparition de nouvelles espèces). Ce phénomène peut être mis à profit par certaines méthodes de lutte contre des maladies vectorielles transmises par les insectes[7].

En dehors des insectes, Wolbachia est capable d’infecter des acariens et des crustacés, mais également des nématodes (elle est même indispensable à leur survie) et notamment ceux responsables de l’onchocercose (Onchocerca volvulus) et de l’éléphantiasis (Wuchereria bancrofti) chez l’Homme. Une large part des symptômes de ces maladies sont dues aux nématodes parasites, mais la bactérie Wolbachia semble jouer un rôle dans ces maladies, notamment de par la réponse immunitaire qu’elle entraîne chez l’homme infecté par le couple nématode/bactérie. Des études récentes montrent qu’un traitement antibiotique permet d’éliminer la bactérie et de stériliser le nématode hébergeant la bactérie.

Des études en laboratoire ont montré que des moustiques Aedes aegypti infectés par des bactéries du genre Wolbachia résistaient mieux aux infections par des parasites tels que le paludisme ou les virus de la dengue ou celui du chikungunya[8] ou encore le virus Zika[9].

L'idée a donc germé d'utiliser ces infections dans un contexte de lutte biologique (dite dans ce cas « autocide »), en élevant et relâchant des moustiques infectés pour in fine diminuer la prévalence de maladies infectieuses chez les humains. Des modélisations semblent démontrer une possible éradication de la maladie par cette méthode[10]. Pour mieux disperser les moustiques infectés dans leur environnement[9] une expérience a consisté, à Townsville en Australie à associer 7 000 familles et des écoles qui ont été invitées à élever et libérer dans leur jardin ou environnement des moustiques (4 millions environ dans ce cas) après qu'ils eurent été infectés par une souche de bactérie Wolbachia réduisant leur capacité à transmettre la dengue, l'infection à virus Zika et le chikungunya[9],[11]. Cette stratégie s'est révélée être efficace en Indonésie où le relargage de moustiques infectés a permis la diminution substantielle des cas de dengue et des hospitalisations pour ce motif dans les secteurs concernés[12]. Elle a également été utilisée avec succès en Nouvelle-Calédonie entre 2019[11] et 2021[13].

Toutefois, cette stratégie consistant finalement à protéger les moustiques (bien que la bactérie puisse aussi limiter leur reproduction) a soulevé des questions car des modèles laissent penser qu'une évolution des parasites ainsi ciblés est possible, pouvant éventuellement les rendre plus virulents[14].

Il existe une autre stratégie de lutte biologique, consistant à utiliser la stérilité de la reproduction entre un mâle Aedes aegypti infecté et une femelle qui ne l'est pas. Dans cette démarche, on inonde un périmètre à traiter avec de très nombreux mâles infectés. Devenus bien plus nombreux que les moustiques mâles non infectés, ils empêchent la naissance d'une nouvelle génération. Le traitement réduit de façon radicale la population de moustiques, sans recours à des insecticides. Mais il doit être renouvelé régulièrement[15].

Wolbachia est un genre de bactéries qui infectent essentiellement des arthropodes, environ 60 % des espèces, ainsi que certaines espèces de nématodes. Cette large répartition en fait donc un des symbiotes les plus répandus du monde animal. Ces bactéries au mode de vie intracellulaire sont localisées au sein du cytoplasme des cellules de leurs hôtes. Elles se retrouvent en proportion importante dans l'appareil reproducteur (principalement les cellules germinales) et l’épithélium du système génital des arthropodes et nématodes.

Leur nom vient de Simeon Burt Wolbach (en) (1880-1954).

Wolbachia é un xénero de bacterias que infecta a artrópodos, incluíndo unha grande proporción das especies de insectos, e tamén a nematodos. É un dos microbios parasitos máis abundantes no mundo e posiblemente é o parasito reprodutivo máis común da biosfera. A súa interacción co hóspede é miúdo complexa, e nalgúns casos evolucionou para ser simbiótico en vez de parasito. Algunhas especies hóspedes non poden reproducirse, ou nin sequera sobrevivir, se non están infectadas por Wolbachia. Un estudo concluíu que máis do 16 % das especies de insectos neotropicais levan bacterias deste xénero,[1] e estímase que do 25 ao 70 % de todos as especies de insectos son hóspedes potenciais.[2]

O xénero identificouse por primeira vez en 1924 por Marshall Hertig e Simeon Burt Wolbach no mosquito Culex pipiens. Hertig describiu formalmente a especie en 1936 como Wolbachia pipientis.[3] En 1971, Janice Yen e A. Ralph Barr da UCLA descubriu que os ovos de Culex morrían debido a unha incompatibilidade citoplásmica cando o esperma dos machos infectados por Wolbachia fertilizaba ovos libres de infección.[4][5] En 1990, Richard Stouthamer da Universidade de California, Riverside descubriu que Wolbachia pode facer que os machos sexan prescindibles nalgunhas especies.[6] A especie segue sendo hoxe de grande interese debido a súa ubicua distribución e as súas moitas e variadas interaccións evolutivas.

Estas bacterias poden infectar diversos órganos, pero son máis notables polas infeccións que producen nos testículos e ovarios dos seus hóspedes. As especies de Wolbachia están presentes nos ovos maduros, pero non no esperma maduro. Isto fai que só as femias infectadas poidan transmitir a infección á súa descendencia. Wolbachia maximiza o seu espallamento ao alterar significativamente as capacidades reprodutivas dos seus hóspedes, por catro mecanismos posibles:

Varias especies son tan dependentes de Wolbachia, que non se poden reproducir se non teñen a bacteria nos seus corpos, e algunhas mesmo non poderían sobrevivir sen a bacteria.[10]

Un estudo sobre o crustáceo isópodo Oniscus asellus infectado mostrou que as liñaxes de individuos infectados tiñan unha maior proporción de femias que os seus conxéneres non infectados.[11]

Wolbachia, especialmente as Wolbachia que causan incompatibilidade citoplasmática, poden ser importantes para favorecer a especiación.[12][13][14] As cepas de Wolbachia que distorsionan a proporción de sexos poden alterar o patrón dos seus hóspedes de selección sexual na natureza,[15][16] e tamén orixinar unha forte selección para impedir a súa acción, dando lugar a algúns dos exemplos máis rápidos de selección natural nas poboacións.[17]

As infeccións por Wolbachia foron asociadas coa resistencia viral na mosca Drosophila melanogaster e en especies de mosquitos. As moscas infectadas pola bacteria son máis resistentes a virus de ARN como o virus de Drosophila C, Nora virus, nodavirus Flock house, virus da parálise do grilo, virus Chikungunya, e virus do Nilo occidental.[18][19][20] No mosquito común, unha densidade alta de Wolbachia foi correlacionada cunha maior resistencia aos insecticidas.[21] No insecto Phyllonorycter blancardella (unha couza minadora de folas), a bacteria Wolbachia axuda aos hóspedes a producir áreas illadas verdes en follas de árbore que están amarelando, o que permite aos adultos continuar alimentándose mentres crecen ata converterse en formas adultas. As larvas tratadas co antibiótico tetraciclina, que mata a Wolbachia, perden esta capacidade e en consecuencia só o 13% delas emerxe con éxito como couza adulta.[22] No nematodo parasito filarial Brugia malayi, Wolbachia converteuse nun endosimbionte obrigado e proporciona ao seu hóspede substancias químicas necesarias para sobrevivir.[23] Combater a bacteria con antibióticos é tamén un método indirecto moi efectivo contra o nematodo.

O primeiro xenoma de Wolbachia que foi determinado foi o da especie que infecta á mosca Drosophila melanogaster.[24] Este xenoma foi secuenciado en The Institute for Genomic Research nunha colaboración entre Jonathan Eisen e Scott O'Neill. O segundo xenoma de Wolbachia secuenciado foi o da especie que infecta ao nematodo Brugia malayi.[25] Están en marcha proxectos de secuenciación de xenomas doutras especies de Wolbachia. Unha copia case completa do xenoma de Wolbachia encontrouse dentro do xenoma da mosca Drosophila ananassae e grandes segmentos do mesmo atopáronse noutras sete especies de Drosophila.[26]

Aplicando a técnica do código de barras do ADN á identificación de especies de moscas Protocalliphora, atopouse que varias morfoespecies distintas tiñan secuencias do xene da citocromo c oxidase I idénticas, o que moi probablemente se debe a que se produciu unha transferencia horizontal de xenes desde as especies de Wolbachia aos hóspedes a medida que a bacteria pasou dunha especie de hóspede a outra.[27] Como resultado, Wolbachia pode causar resultados errados nas análises de cladística molecular.[28]

Pola súa parte, Wolbachia tamén alberga un bacteriófago temperado chamado WO.[29] As análises de secuencia comparativas do bacteriófago WO ofrecen algúns dos exemplos máis claros de transferencia horizontal de xenes a grande escala entre coinfeccións de Wolbachia no mesmo hóspede.[30] Este é o primeiro bacteriófago implicado na transferencia horizontal de xenes frecuente entre os xenomas de endosimbiontes bacterianos. A transferencia de xenes realizada por bacteriófagos pode producir un cambio evolutivo significativo nos xenomas das bacterias intracelulares.

Ademais de a insectos, Wolbachia infecta a varias especies de crustáceos isópodos, arácnidos, e moitas especies de vermes nematodos (filarias parasitas), entre as que se inclúen as que causan oncocercose (causada por Onchocerca volvulus ) e elefantíase en humanos e certas infestacións de vermes en cans (Dirofilaria immitis). A Wolbachia non se limita a infectar aos vermes, senón que a Wolbachia parece xogar un papel pouco común nestas doenzas humanas parasitarias. Unha grande parte da patoxenicidade destes nematodos débese á resposta do sistema inmunitario do hóspede contra a Wolbachia. A eliminación da Wolbachia dos nematodos orixina xeralmente a morte ou a esterilidade do verme.[31] En consecuencia, unha estratexia actual para o control das enfermidades producidas polos nematodos filariais é a eliminación de Wolbachia por medio do antibiótico doxiciclina en vez de utilizar medicacións antinematodos, que son máis tóxicas.[32]

Tamén se investigou o uso das cepas que existen na natureza de Wolbachia para controlar as poboacións de mosquitos.[33][34] Wolbachia pode ser utilizado para controlar o dengue e a malaria eliminando os insectos máis vellos que son os que conteñen máis parasitos. Permitir aos insectos máis novos sobrevivir e reproducirse diminúe a presión de selección que fai que evolucionen resistencias.[35][36] A infección por Wolbachia pode tamén incrementar a resistencia dos mosquitos á malaria, como se puido comprobar no mosquito Anopheles stephensi, no que a cepa wAlbB de Wolbachia perturba o ciclo vital do Plasmodium falciparum causante da malaria.[37]

Wolbachia é un xénero de bacterias que infecta a artrópodos, incluíndo unha grande proporción das especies de insectos, e tamén a nematodos. É un dos microbios parasitos máis abundantes no mundo e posiblemente é o parasito reprodutivo máis común da biosfera. A súa interacción co hóspede é miúdo complexa, e nalgúns casos evolucionou para ser simbiótico en vez de parasito. Algunhas especies hóspedes non poden reproducirse, ou nin sequera sobrevivir, se non están infectadas por Wolbachia. Un estudo concluíu que máis do 16 % das especies de insectos neotropicais levan bacterias deste xénero, e estímase que do 25 ao 70 % de todos as especies de insectos son hóspedes potenciais.

Wolbachia adalah salah satu genus bakteri yang hidup sebagai parasit pada hewan artropoda.[1] Infeksi Wolbachia pada hewan akan menyebabkan partenogenesis (perkembangan sel telur yang tidak dibuahi), kematian pada hewan jantan, dan feminisasi (perubahan serangga jantan menjadi betina).[1] Bakteri ini tergolong ke dalam gram negatif, berbentuk batang, dan sulit ditumbuhkan di luar tubuh inangnya.[2] Berdasarkan studi filogenomik, Wolbachia dikelompokkan menjadi 8 kelompok utama (A-H). Bakteri tersebut banyak terdapat di dalam jaringan dan organ reproduksi hewan serta pada jaringan somatik. Inang yang terinfeksi dapat mengalami inkompatibilitas (ketidakserasian) sitoplasma, yaitu suatu fenomena penyebaran faktor sitoplasma yang umumnya dilakukan dengan membunuh progeni (keturunan) yang tidak membawa/mewarisi faktor tersebut.[3]

Wolbachia adalah salah satu genus bakteri yang hidup sebagai parasit pada hewan artropoda. Infeksi Wolbachia pada hewan akan menyebabkan partenogenesis (perkembangan sel telur yang tidak dibuahi), kematian pada hewan jantan, dan feminisasi (perubahan serangga jantan menjadi betina). Bakteri ini tergolong ke dalam gram negatif, berbentuk batang, dan sulit ditumbuhkan di luar tubuh inangnya. Berdasarkan studi filogenomik, Wolbachia dikelompokkan menjadi 8 kelompok utama (A-H). Bakteri tersebut banyak terdapat di dalam jaringan dan organ reproduksi hewan serta pada jaringan somatik. Inang yang terinfeksi dapat mengalami inkompatibilitas (ketidakserasian) sitoplasma, yaitu suatu fenomena penyebaran faktor sitoplasma yang umumnya dilakukan dengan membunuh progeni (keturunan) yang tidak membawa/mewarisi faktor tersebut.

Wolbachia è un genere di batteri Gram-negativi, non sporigeni, parassiti intracellulari obbligati che infetta diverse specie di artropodi, inclusa un'alta porzione di insetti (circa il 60% delle specie), come pure alcuni nematodi.

È uno dei microbi parassiti più comuni del mondo ed è forse il più comune parassita della biosfera che agisca a livello del sistema riproduttivo. Uno studio è giunto alla conclusione che oltre il 16% delle specie di insetti siano portatori di questo batterio[1] ed addirittura il 25-70% di tutte le specie di insetti sia un potenziale ospite[2]. Le interazioni ospite-parassita sono spesso complesse e in molti casi evolute in senso simbiotico più che parassitico.

Il batterio è stato identificato nel 1924 da Marshall Hertig e S. Burt Wolbach nella zanzara comune (Culex pipiens). Hertig lo descrisse formalmente nel 1936 dandogli il nome di Wolbachia pipientis[3]. Tale scoperta rimase confinata in pochi ambienti, per lo scarso interesse, fino al 1971 quando Janice Yen e Ralph A. Barr della University of California a Los Angeles scoprirono che le uova di zanzara Culex venivano uccise per una particolare incompatibilità citoplasmatica quando lo sperma dei maschi proveniva da individui portatori di Wolbachia[4].