pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

Die Graptolithen (Schriftsteine) sind eine ausgestorbene Klasse polypenähnlicher, koloniebildender mariner Tiere, die gemeinhin bei den Kiemenlochtieren (Hemichordata) eingeordnet werden.

Fossil überliefert sind nur die Wohnröhren, die einen Kammeraufbau aufweisen. Die Hemichordaten-Verwandtschaft ergibt sich aus histologischen Untersuchungen und ist so eng, dass manche Forscher (wie Wladimir N. Beklemischew) die Pterobranchia geradezu als überlebende Graptolit(h)en auffassen. Nach der Entdeckung des Pterobranchen Cephalodiscus graptolitoides, der bei Neukaledonien in großer Tiefe gefunden wurde, sind andere Wissenschaftler der Ansicht, dass die Graptolithen bei den Pterobranchen eingeordnet werden müssen, da die fossilierbaren Teile von Cephalodiscus graptolithoides einem Graptolithen zum Verwechseln ähnlich sind, während der lebende Organismus ein gewöhnlicher Pterobranche ist.[1]

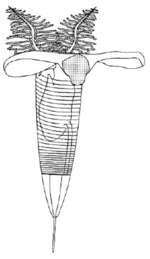

Die Lebensweise der Graptolithen war zu Beginn ihrer Stammesgeschichte sessil-benthisch. Im weiteren Verlauf ihrer Evolution entwickelten sich planktische Arten. Die Bauweise der Graptolithen wies ein Wachstum entlang einer oder mehrerer Achsen auf. Je nachdem, ob die Wohnkammern (Theken) entlang der Achsen einreihig oder mehrreihig angeordnet waren, werden Monograptiden (1 Reihe), Diplograptiden (2 Reihen) oder Phyllograptiden (4 Reihen) unterschieden. Die Kolonien hatten eine oder mehrere Achsen mit geraden oder gebogenen Wuchsformen.

Das möglicherweise einzigartige Strukturprotein (Skleroprotein, Gerüsteiweiß) dieser Tiergruppe ist das Graptin. Es ist in seinem Aufbau dem Chitin ähnlich. Erstmals beschrieben wurde es 1973 von Roman Kozłowski.[2]

Aufgrund der zeitlich raschen Entwicklung der Klasse, ihrer weiten Verbreitung und den makroskopisch leicht erkennbaren Fossilien sind die Graptolithen vorzügliche Leitfossilien vom Oberkambrium bis ins Unterdevon. Graptolithen sind vor allem in Schiefern (Graptolithenschiefer) überliefert.

Die Graptolithen werden in sechs Ordnungen unterteilt:

Die Graptolithen (Schriftsteine) sind eine ausgestorbene Klasse polypenähnlicher, koloniebildender mariner Tiere, die gemeinhin bei den Kiemenlochtieren (Hemichordata) eingeordnet werden.

Fossil überliefert sind nur die Wohnröhren, die einen Kammeraufbau aufweisen. Die Hemichordaten-Verwandtschaft ergibt sich aus histologischen Untersuchungen und ist so eng, dass manche Forscher (wie Wladimir N. Beklemischew) die Pterobranchia geradezu als überlebende Graptolit(h)en auffassen. Nach der Entdeckung des Pterobranchen Cephalodiscus graptolitoides, der bei Neukaledonien in großer Tiefe gefunden wurde, sind andere Wissenschaftler der Ansicht, dass die Graptolithen bei den Pterobranchen eingeordnet werden müssen, da die fossilierbaren Teile von Cephalodiscus graptolithoides einem Graptolithen zum Verwechseln ähnlich sind, während der lebende Organismus ein gewöhnlicher Pterobranche ist.

Die Lebensweise der Graptolithen war zu Beginn ihrer Stammesgeschichte sessil-benthisch. Im weiteren Verlauf ihrer Evolution entwickelten sich planktische Arten. Die Bauweise der Graptolithen wies ein Wachstum entlang einer oder mehrerer Achsen auf. Je nachdem, ob die Wohnkammern (Theken) entlang der Achsen einreihig oder mehrreihig angeordnet waren, werden Monograptiden (1 Reihe), Diplograptiden (2 Reihen) oder Phyllograptiden (4 Reihen) unterschieden. Die Kolonien hatten eine oder mehrere Achsen mit geraden oder gebogenen Wuchsformen.

Das möglicherweise einzigartige Strukturprotein (Skleroprotein, Gerüsteiweiß) dieser Tiergruppe ist das Graptin. Es ist in seinem Aufbau dem Chitin ähnlich. Erstmals beschrieben wurde es 1973 von Roman Kozłowski.

Aufgrund der zeitlich raschen Entwicklung der Klasse, ihrer weiten Verbreitung und den makroskopisch leicht erkennbaren Fossilien sind die Graptolithen vorzügliche Leitfossilien vom Oberkambrium bis ins Unterdevon. Graptolithen sind vor allem in Schiefern (Graptolithenschiefer) überliefert.

Graptolites are a group of colonial animals, members of the subclass Graptolithina within the class Pterobranchia. These filter-feeding organisms are known chiefly from fossils found from the Middle Cambrian (Miaolingian, Wuliuan) through the Lower Carboniferous (Mississippian).[3] A possible early graptolite, Chaunograptus, is known from the Middle Cambrian.[1] Recent analyses have favored the idea that the living pterobranch Rhabdopleura represents an extant graptolite which diverged from the rest of the group in the Cambrian.[2] Fossil graptolites and Rhabdopleura share a colony structure of interconnected zooids housed in organic tubes (theca) which have a basic structure of stacked half-rings (fuselli). Most extinct graptolites belong to two major orders: the bush-like sessile Dendroidea and the planktonic, free-floating Graptoloidea. These orders most likely evolved from encrusting pterobranchs similar to Rhabdopleura. Due to their widespread abundance, plantkonic lifestyle, and well-traced evolutionary trends, graptoloids in particular are useful index fossils for the Ordovician and Silurian periods.[4]

The name graptolite comes from the Greek graptos meaning "written", and lithos meaning "rock", as many graptolite fossils resemble hieroglyphs written on the rock. Linnaeus originally regarded them as 'pictures resembling fossils' rather than true fossils, though later workers supposed them to be related to the hydrozoans; now they are widely recognized as hemichordates.[4]

The name "graptolite" originates from the genus Graptolithus ("writing on the rocks"), which was used by Linnaeus in 1735 for inorganic mineralizations and incrustations which resembled actual fossils. In 1768, in the 12th volume of Systema Naturae, he included G. sagittarius and G. scalaris, respectively a possible plant fossil and a possible graptolite. In his 1751 Skånska Resa, he included a figure of a "fossil or graptolite of a strange kind" currently thought to be a type of Climacograptus (a genus of biserial graptolites).

Graptolite fossils were later referred to a variety of groups, including other branching colonial animals such as bryozoans ("moss animals") and hydrozoans. The term Graptolithina was established by Bronn in 1849, who considered them to represent orthoconic cephalopods. By the mid-20th century, graptolites were recognized as a unique group closely related to living pterobranchs in the genera Rhabdopleura and Cephalodiscus, which had been described in the late 19th century. Graptolithus, as a genus, was officially abandoned in 1954 by the ICZN.[5]

Each graptolite colony originates from an initial individual, called the sicular zooid, from which the subsequent zooids will develop. They are all interconnected by stolons, a true colonial system shared by Rhabdopleura but not Cephalodiscus. These zooids are housed within an organic structure comprising a series of tubes secreted by the glands on the cephalic shield. The colony structure has been known from several different names, including coenecium (for living pterobranchs), rhabdosome (for fossil graptolites), and most commonly tubarium (for both). The individual tubes, each occupied by a single zooid, are known as theca.[4] The composition of the tubarium is not clearly known, but different authors suggest it is made out of collagen or chitin. In some colonies, there are two sizes of theca, the larger autotheca and smaller bitheca, and it has been suggested that this difference is due to sexual dimorphism of zooids within a colony.[4]

Early in the development of a colony, the tubarium splits into a variable number of branches (known as stipes) and different arrangements of the theca, features which are important in the identification of graptolite fossils. Colonies can be classified by their total number of theca rows (biserial colonies have two rows, uniserial have one) and the number of initial stipes per colony (multiramous colonies have many stipes, pauciramous colonies have two or fewer). Each thecal tube is mostly made up by two series of stacked semicircular half-rings, known as fuselli (sing: fusellum). The fuselli resemble growth lines when preserved in fossils, and the two stacks meet along a suture with a zig-zag pattern. Fuselli are the major reinforcing component of a tubarium, though they are assisted by one or more additional layers of looser tissue, the cortex.

The earliest graptolites appeared in the fossil record during the Cambrian, and were generally sessile animals, with a colony attached to the sea floor. Several early-diverging families were encrusting organisms, with the colony developing horizontally along a substrate. Extant Rhabdopleura fall into this category, with an overall encrusting colony form combined with erect, vertical theca. Most of the erect, dendritic or bushy/fan-shaped graptolites are classified as dendroids (order Dendroidea). Their colonies were attached to a hard substrate by their own weight via an attachment disc. Graptolites with relatively few branches were derived from the dendroid graptolites at the beginning of the Ordovician period. This latter major group, the graptoloids (order Graptoloidea) were pelagic and planktonic, drifting freely through the water column. They were a successful and prolific group, being the most important and widespread macroplanktonic animals until they died out in the early part of the Devonian period. The dendroid graptolites survived until the Carboniferous period.

A mature zooid has three important regions, the preoral disc or cephalic shield, the collar and the trunk. In the collar, the mouth and anus (U-shaped digestive system) and arms are found; Graptholitina has a single pair of arms with several paired tentacles. As a nervous system, graptolites have a simple layer of fibers between the epidermis and the basal lamina, also have a collar ganglion that gives rise to several nerve branches, similar to the neural tube of chordates.[6] All this information was inferred by the extant Rhabdopleura, however, it is very likely that fossil zooids had the same morphology.[4]

Since the 1970s, as a result of advances in electron microscopy, graptolites have generally been thought to be most closely allied to the pterobranchs, a rare group of modern marine animals belonging to the phylum Hemichordata.[7] Comparisons are drawn with the modern hemichordates Cephalodiscus and Rhabdopleura. According to recent phylogenetic studies, rhabdopleurids are placed within the Graptolithina. Nonetheless, they are considered an incertae sedis family.[3]

On the other hand, Cephalodiscida is considered to be a sister subclass of Graptolithina. One of the main differences between these two groups is that Cephalodiscida species are not a colonial organisms. In Cephalodiscida organisms, there is no common canal connecting all zooids. Cephalodiscida zooids have several arms, while Graptolithina zooids have only one pair of arms. Other differences include the type of early development, the gonads, the presence or absence of gill slits, and the size of the zooids. However, in the fossil record where mostly tubaria (tubes) are preserved, it is complicated to distinguish between groups.

Phylogeny of Pterobranchia[3] Graptolithina EugraptolithinaGraptolithina includes several minor families as well as two main extinct orders, Dendroidea (benthic graptolites) and Graptoloidea (planktic graptolites). The latter is the most diverse, including 5 suborders, where the most assorted is Axonophora (biserial graptolites, etc.). This group includes Diplograptids and Neograptids, groups that had a great development during the Ordovician.[3] Old taxonomic classifications consider the orders Dendroidea, Tuboidea, Camaroidea, Crustoidea, Stolonoidea, Graptoloidea, and Dithecoidea but new classifications embedded them into Graptoloidea at different taxonomic levels.

Taxonomy of Graptolithina by Maletz (2014):[3][4]

Subclass Graptolithina Bronn, 1849

Graptolites were a major component of the early Paleozoic ecosystems, especially for the zooplankton because the most abundant and diverse species were planktonic. Graptolites were most likely suspension feeders and strained the water for food such as plankton.[8]

Inferring by analogy with modern pterobranchs, they were able to migrate vertically through the water column for feeding efficiency and to avoid predators. With ecological models and studies of the facies, it was observed that, at least for Ordovician species, some groups of species are largely confined to the epipelagic and mesopelagic zone, from inshore to open ocean.[9] Living rhabdopleura have been found in deep waters in several regions of Europe and America but the distribution might be biased by sampling efforts; colonies are usually found as epibionts of shells.

Their locomotion was relative to the water mass in which they lived but the exact mechanisms (such as turbulence, buoyancy, active swimming, and so forth) are not clear yet. One proposal, put forward by Melchin and DeMont (1995), suggested that graptolite movement was analogous to modern free-swimming animals with heavy housing structures. In particular, they compared graptolites to "sea butterflies" (Thecostomata), small swimming pteropod snails. Under this suggestion, graptolites moved through rowing or swimming via an undulatory movement of paired muscular appendages developed from the cephalic shield or feeding tentacles. However, in some species, the thecal aperture was probably so restricted that the appendages hypothesis is not feasible. On the other hand, buoyancy is not supported by any extra thecal tissue or gas build-up control mechanism, and active swimming requires a lot of energetic waste, which would rather be used for the tubarium construction.[9]

There are still many questions regarding graptolite locomotion but all these mechanisms are possible alternatives depending on the species and its habitat. For benthic species, that lived attached to the sediment or any other organism, this was not a problem; the zooids were able to move but restricted within the tubarium. Although this zooid movement is possible in both planktic and benthic species, it is limited by the stolon but is particularly useful for feeding. Using their arms and tentacles, which are close to the mouth, they filter the water to catch any particles of food.[9]

The study of the developmental biology of Graptholitina has been possible by the discovery of the species R. compacta and R. normani in shallow waters; it is assumed that graptolite fossils had a similar development as their extant representatives. The life cycle comprises two events, the ontogeny and the astogeny, where the main difference is whether the development is happening in the individual organism or in the modular growth of the colony.

The life cycle begins with a planktonic planula-like larva produced by sexual reproduction, which later becomes the sicular zooid who starts a colony. In Rhabdopleura, the colonies bear male and female zooids but fertilized eggs are incubated in the female tubarium, and stay there until they become larvae able to swim (after 4–7 days) to settle away to start a new colony. Each larva surrounds itself in a protective cocoon where the metamorphosis to the zooid takes place (7–10 days) and attaches with the posterior part of the body, where the stalk will eventually develop.[4]

The development is indirect and lecithotrophic, and the larvae are ciliated and pigmented, with a deep depression on the ventral side.[10][6] Astogeny happens when the colony grows through asexual reproduction from the tip of a permanent terminal zooid, behind which the new zooids are budded from the stalk, a type of budding called monopodial. It is possible that in graptolite fossils the terminal zooid was not permanent because the new zooids formed from the tip of latest one, in other words, sympodial budding. These new organisms break a hole in the tubarium wall and start secreting their own tube.[4]

In recent years, living graptolites have been used as a hemichordate model for Evo-Devo studies, as have their sister group, the acorn worms. For example, graptolites are used to study asymmetry in hemichordates, especially because their gonads tend to be located randomly on one side. In Rhabdopleura normani, the testicle is located asymmetrically, and possibly other structures such as the oral lamella and the gonopore.[11] The significance of these discoveries is to understand the early vertebrate left-right asymmetry due to chordates being a sister group of hemichordates, and therefore, the asymmetry might be a feature that developed early in deuterostomes. Since the location of the structures is not strictly established, also in some enteropneusts, it is likely that asymmetrical states in hemichordates are not under a strong developmental or evolutionary constraint. The origin of this asymmetry, at least for the gonads, is possibly influenced by the direction of the basal coiling in the tubarium, by some intrinsic biological mechanisms in pterobranchs, or solely by environmental factors.[11]

Hedgehog (hh), a highly conserved gene implicated in neural developmental patterning, was analyzed in Hemichordates, taking Rhabdopleura as a pterobranch representative. It was found that hedgehog gene in pterobranchs is expressed in a different pattern compared to other hemichordates as the enteropneust Saccoglossus kowalevskii. An important conserved glycine–cysteine–phenylalanine (GCF) motif at the site of autocatalytic cleavage in hh genes, is altered in R. compacta by an insertion of the amino acid threonine (T) in the N-terminal, and in S. kowalesvskii there is a replacement of serine (S) for glycine (G). This mutation decreases the efficiency of the autoproteolytic cleavage and therefore, the signalling function of the protein. It is not clear how this unique mechanism occurred in evolution and the effects it has in the group, but, if it has persisted over millions of years, it implies a functional and genetic advantage.[12]

Graptolites are common fossils and have a worldwide distribution. They are most commonly found in shales and mudrocks where sea-bed fossils are rare, this type of rock having formed from sediment deposited in relatively deep water that had poor bottom circulation, was deficient in oxygen, and had no scavengers. The dead planktic graptolites, having sunk to the sea floor, would eventually become entombed in the sediment and were thus well preserved.

These colonial animals are also found in limestones and cherts, but generally these rocks were deposited in conditions which were more favorable for bottom-dwelling life, including scavengers, and undoubtedly most graptolite remains deposited here were generally eaten by other animals.

Fossils are often found flattened along the bedding plane of the rocks in which they occur, though may be found in three dimensions when they are infilled by iron pyrite or some other minerals. They vary in shape, but are most commonly dendritic or branching (such as Dictyonema), sawblade-like, or "tuning fork"-shaped (such as Didymograptus murchisoni). Their remains may be mistaken for fossil plants by the casual observer, as it has been the case for the first graptolite descriptions.

Graptolites are normally preserved as a black carbon film on the rock's surface or as light grey clay films in tectonically distorted rocks. The fossil can also appear stretched or distorted. This is due to the strata that the graptolite is within, being folded and compacted. They may be sometimes difficult to see, but by slanting the specimen to the light they reveal themselves as a shiny marking. Pyritized graptolite fossils are also found.

A well-known locality for graptolite fossils in Britain is Abereiddy Bay, Dyfed, Wales, where they occur in rocks from the Ordovician Period. Sites in the Southern Uplands of Scotland, the Lake District and Welsh Borders also yield rich and well-preserved graptolite faunas. A famous graptolite location in Scotland is Dob's Linn with species from the boundary Ordovician-Silurian. However, since the group had a wide distribution, they are also abundantly found in several localities in the United States, Canada, Australia, Germany, China, among others.

Graptolite fossils have predictable preservation, widespread distribution, and gradual change over a geologic time scale. This allows them to be used to date strata of rocks throughout the world.[7] They are important index fossils for dating Palaeozoic rocks as they evolved rapidly with time and formed many different distinctive species. Geologists can divide the rocks of the Ordovician and Silurian periods into graptolite biozones; these are generally less than one million years in duration. A worldwide ice age at the end of the Ordovician eliminated most graptolites except the neograptines. Diversification from the neograptines that survived the Ordovician glaciation began around 2 million years later.[13]

The Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event (GOBE) influenced changes in the morphology of the colonies and thecae, giving rise to new groups like the planktic Graptoloidea. Later, some of the greatest extinctions that affected the group were the Hirnantian in the Ordovician and the Lundgreni in the Silurian, where graptolite populations were dramatically reduced (see also Lilliput effect).[4][14]

The following is a selection of graptolite and pterobranch researchers:[4]

Graptolites are a group of colonial animals, members of the subclass Graptolithina within the class Pterobranchia. These filter-feeding organisms are known chiefly from fossils found from the Middle Cambrian (Miaolingian, Wuliuan) through the Lower Carboniferous (Mississippian). A possible early graptolite, Chaunograptus, is known from the Middle Cambrian. Recent analyses have favored the idea that the living pterobranch Rhabdopleura represents an extant graptolite which diverged from the rest of the group in the Cambrian. Fossil graptolites and Rhabdopleura share a colony structure of interconnected zooids housed in organic tubes (theca) which have a basic structure of stacked half-rings (fuselli). Most extinct graptolites belong to two major orders: the bush-like sessile Dendroidea and the planktonic, free-floating Graptoloidea. These orders most likely evolved from encrusting pterobranchs similar to Rhabdopleura. Due to their widespread abundance, plantkonic lifestyle, and well-traced evolutionary trends, graptoloids in particular are useful index fossils for the Ordovician and Silurian periods.

The name graptolite comes from the Greek graptos meaning "written", and lithos meaning "rock", as many graptolite fossils resemble hieroglyphs written on the rock. Linnaeus originally regarded them as 'pictures resembling fossils' rather than true fossils, though later workers supposed them to be related to the hydrozoans; now they are widely recognized as hemichordates.

Los graptolitoideos (Graptolithina) o graptolitos (del griego γραπτή, graptí, 'escrito', y λίθος líthos, 'piedra') son una clase extinta del filo Hemichordata. Son fósiles de animales coloniales conocidos principalmente del Cámbrico Superior al Carbonífero Inferior (Misisípico). Un graptolito ligeramente más antiguo, Chaunograptus, se conoce desde el Cámbrico Medio.[1] El nombre viene del griego graptos, que significa "escrito" y lithos que significa "piedra", ya que muchos fósiles de graptolitos se asemejan a jeroglíficos escritos en la roca. Los graptolitos por lo general se consideran hemicordados, un raro grupo de animales marinos que comprenden los modernos pterobranquios. La relación se ha establecido sobre la base de comparaciones con los hemicordados modernos Cephalodiscus y Rhabdopleura.[2]

Cada colonia de graptolitos (conocida como rabdosoma) tiene un número variable de ramas (llamadas estipes) originadas desde un individuo inicial (llamado sícula). Los individuos subsiguientes (zooides) se alojan en una estructura tubular o con forma de copa. En algunas colonias hay dos tamaños de teca y se ha sugerido que esta diferencia podría estar debida al dimorfismo sexual. El número de las ramificaciones y la disposición de las tecas son características importantes para la identificación taxonómica de los fósiles de graptolitos.

La mayoría de los tipos dendríticos o con ramificaciones múltiples se clasifican en los graptolitos dendroideos (orden Dendroidea). Estos son los primeros, los más antiguos, que aparecen en el registro fósil (en el período Cámbrico), y en general fueron animales bentónicos (unidos al fondo marino por una base similar a una raíz). Los graptolitos dendroides sobrevivieron hasta el período Carbonífero.

Los graptolitos con relativamente pocas ramas (orden Graptoloidea) se derivaron a partir de los graptolitos dendroides al comienzo del período Ordovícico. Fueron pelágicos, flotando libremente sobre la superficie del antiguo mar, unidos a algas flotantes por medio de un delgado hilo o alguna especie de aceite de menor densidad. Este fue un prolífico y exitoso grupo, siendo los animales más importantes del plancton hasta que desaparecieron en la primera parte del Devónico, antes que los dendroides.

Los graptolitos son fósiles comunes y tienen una distribución mundial. La preservación, cantidad y cambio gradual permite que se usen como fósiles guía para datar los estratos de rocas en todo el mundo. Durante el Paleozoico los graptolitos evolucionaron rápidamente y dieron lugar a muchas especies diferentes. Los geólogos británicos pueden dividir las rocas de los períodos Ordovícico y Silúrico en biozonas de graptolitos; que por lo general tienen una duración menor de un millón de años. Una glaciación en todo el mundo al final del Ordovícico eliminó la mayoría de las especies de graptolitos que vivían entonces; las especies presentes durante el período Silúrico fueron el resultado de la diversificación de sólo una o dos especies que sobrevivieron a la glaciación del Ordovícico.[2] Los graptolitos también se utilizan para estimar la profundidad del agua y la temperatura en la que vivían estos organismos.

Los fósiles de graptolitos a menudo se encuentran en pizarras y arcillas donde los fósiles marinos son raros. Este tipo de roca se suele formar a partir de sedimentos depositados en aguas relativamente profundas con poca circulación, deficiente en oxígeno y carente de organismos excavadores. Los graptolitos planctónicos muertos, después de hundirse al fondo marino, se enterrarían en los sedimentos pobres en oxígeno y, por tanto, fueron bien conservados. Los graptolitos también se encuentran en calizas y sílex, pero en general estas rocas fueron depositadas en condiciones que son más favorables para la preservación de los organismos del fondo marino, incluyendo excavadores, y, sin duda, la mayoría de graptolitos depositados aquí fueron, en general, devorados por otros animales.

Los fósiles de graptolitos se encuentran a menudo aplastados dentro de las rocas, aunque algunos se pueden encontrar en tres dimensiones cuando se infiltran en pirita férrica. Varían en forma, pero son más comúnmente dendríticos o ramificados (como Dictoyonema), con hojas, o con forma de "diapasón" (como Didymograptus murchisoni). Sus restos puede confundirse con fósiles de plantas al observador casual.

Los graptolitos normalmente se conservan como una película negra carbonizada sobre la superficie de la roca o como una película gris clara de arcilla en rocas tectónicamente distorsionadas. A veces pueden ser difíciles de ver, pero puestos a luz de perfil se revelan como un marcado brillante. También se encuentran graptolitos fósiles piritizados.

Los graptolitoideos (Graptolithina) o graptolitos (del griego γραπτή, graptí, 'escrito', y λίθος líthos, 'piedra') son una clase extinta del filo Hemichordata. Son fósiles de animales coloniales conocidos principalmente del Cámbrico Superior al Carbonífero Inferior (Misisípico). Un graptolito ligeramente más antiguo, Chaunograptus, se conoce desde el Cámbrico Medio. El nombre viene del griego graptos, que significa "escrito" y lithos que significa "piedra", ya que muchos fósiles de graptolitos se asemejan a jeroglíficos escritos en la roca. Los graptolitos por lo general se consideran hemicordados, un raro grupo de animales marinos que comprenden los modernos pterobranquios. La relación se ha establecido sobre la base de comparaciones con los hemicordados modernos Cephalodiscus y Rhabdopleura.

Graptolithina

Les graptolites (Graptolithina)[note 1] sont une classe d'animaux vivant en colonies (de trois à plusieurs milliers d'individus) et rattachés à l'embranchement des Hemichordata. Ils ont été découverts dans les couches géologiques du Cambrien supérieur jusqu'au Dinantien (Carbonifère inférieur). Leur apparition dès le Cambrien moyen est possible, selon la classification exacte d'un genre de graptolite probable, Chaunograptus (en).

Ressemblant à des polypes de coraux composés de tubes enroulés et dentelés, ces animaux coloniaux sont réunis autour d'une tige principale sur laquelle sont fixées de petites alvéoles où vit chaque spécimen.

Animaux ayant évolué rapidement et retrouvés dans le monde entier, ils forment d'excellents fossiles stratigraphiques très utilisés pour la datation des couches d'une grande partie du Paléozoïque, ayant notamment permis une analyse très fine des assises siluriennes. Leur étude détaillée a été initiée par Charles Lapworth (1842-1920), qui a démontré leur intérêt en tant qu'index géologique. Les géologues continuent de l'utiliser comme marqueur paléoécologique et paléobiogéographique.

Considéré comme un groupe éteint depuis 300 millions d’années, des chercheurs ont toutefois découvert des organismes très semblables, en 1989 en Nouvelle-Calédonie près de l'île de Lifou. Ils sont attribués aux Graptolites (Cephalodiscus graptolitoides) en 1993 par le Professeur Dilly[1].

Les colonies de graptolites, appelées rhabdosomes, sont constituées à partir d'un individu initial appelé sicule (ou sicula). Un stolon chitinisé constitue l'axe central de la colonie ; il possède un nombre variable de branches, les stypes. Le stolon comporte une série de thèques, petites loges latérales où vivent les individus constituant la colonie. Leur taille va de 2 mm à 1 m de longueur[2].

Certains graptolites vivent à la surface des océans (forme planctonique fixée à un corps flottant ou libres), dérivant au gré des courants, d'autres munis d'un appareil de fixation (forme benthique, la plupart des Dendroïdes) sont rattachés à des algues par de fins filaments ou au fond des mers par des sortes de racines.

Leurs fossiles sont souvent trouvés dans des schistes noirs et fins, et de l'ardoise, correspondant à un dépôt en mer calme, de profondeur réduite. Dans ces couches les fossiles des fonds marins sont rares, ce type de couche se formant en eau relativement peu profonde, déficiente en oxygène et sans population d'animaux nécrophages[2].

Des graptolites bien conservés peuvent être trouvés dans du calcaire ou du grès, mais généralement ces roches se sont déposées dans des conditions favorables à une vie sur le fond marin incluant des nécrophages, aussi il n'y a guère de doutes que la plupart des graptolites morts y ont été dévorés avant de pouvoir se fossiliser[2].

Les fossiles sont aplatis dans le sens du dépôt des couches, en général en forme de dendrites ou de branches. Leurs restes peuvent être confondus avec des fossiles de plantes.

La classification des graptolites est encore sujette à caution. De nos jours ils sont considérés comme possédant un ancêtre commun avec les vertébrés.

La classe des Graptolithina se subdivise en deux ordres :

Les dendroïdes sont plus primitifs (Cambrien supérieur) et souvent « enracinés » sur le fond marin. Les Graptoloidea se sont séparés des dendroïdes (mode de vie planctonique) au début de l'Ordovicien, probablement en passant par des stades pseudo-planctoniques, et sont prolifiques jusqu'au début du Dévonien. À partir de ce système, seules les formes les plus primitives survivent, pour s’éteindre au Carbonifère inférieur.

Le nom graptolite provient du grec graptos et lithos, littéralement écrit sur la pierre, beaucoup de graptolites ressemblant à des hiéroglyphes écrits sur le roc.

Graptolithina

Les graptolites (Graptolithina) sont une classe d'animaux vivant en colonies (de trois à plusieurs milliers d'individus) et rattachés à l'embranchement des Hemichordata. Ils ont été découverts dans les couches géologiques du Cambrien supérieur jusqu'au Dinantien (Carbonifère inférieur). Leur apparition dès le Cambrien moyen est possible, selon la classification exacte d'un genre de graptolite probable, Chaunograptus (en).

Ressemblant à des polypes de coraux composés de tubes enroulés et dentelés, ces animaux coloniaux sont réunis autour d'une tige principale sur laquelle sont fixées de petites alvéoles où vit chaque spécimen.

Animaux ayant évolué rapidement et retrouvés dans le monde entier, ils forment d'excellents fossiles stratigraphiques très utilisés pour la datation des couches d'une grande partie du Paléozoïque, ayant notamment permis une analyse très fine des assises siluriennes. Leur étude détaillée a été initiée par Charles Lapworth (1842-1920), qui a démontré leur intérêt en tant qu'index géologique. Les géologues continuent de l'utiliser comme marqueur paléoécologique et paléobiogéographique.

Considéré comme un groupe éteint depuis 300 millions d’années, des chercheurs ont toutefois découvert des organismes très semblables, en 1989 en Nouvelle-Calédonie près de l'île de Lifou. Ils sont attribués aux Graptolites (Cephalodiscus graptolitoides) en 1993 par le Professeur Dilly.

I graptoliti, tra cui i Monograptus, sono fossili guida (organismi acquatici che hanno avuto un'ampia distribuzione geografica) del Paleozoico (570-225 milioni di anni fa). Sono molto comuni come fossili e si trovano spesso associati a sedimenti depositatisi in fondali marini.

Sono stati a lungo considerati solo resti organici e riconosciuti come veri e propri organismi animali nel 1821. Il loro nome ("scrittura di pietra") deriva dalla loro particolare forma, simile a una scrittura cuneiforme. I graptoliti sono un gruppo estinto di organismi marini coloniali, con esoscheletro chitinoso, vissuti dal Cambriano al Carbonifero. Gli animali (zooidi) avevano corpo molle, vermiforme, e alloggiavano in teche disposte su 1-2 file lungo i rami della colonia (rabdosomi). Dalle teche partiva un filamento (virgula) col quale l'organismo si fissava a un galleggiante (pneumatoforo).

Le colonie di Monograptus avevano un solo ramo che poteva assumere forme diverse (rettilinea, ricurva, spiralata) di grande importanza per la classificazione delle specie.

Os graptólitos foram organismos coloniais pertencentes à classe Graptolithina (do grego graptos, escrita + lithos, rocha) do filo Hemichordata, que habitaram os mares do Paleozoico. O grupo surgiu no Câmbrico superior e extinguiu-se no Carbónico inferior (ca. 523 – ca. 330 milhões de anos).

A colónia de graptólitos era constituida por um esqueleto colonial, o rabdossoma, composto por várias cápsulas denominadas tecas que albergavam os organismos indivíduais. As tecas eram compostas de colagénio e uniam-se umas às outras através do nema que suportava a estrutura. Os rabdossomas dos graptólitos podem apresentar uma ou várias estirpes, ou ramos, e são classificados pelos paleontólogos de acordo com a relação geométrica entre estirpes e nema. Devido à natureza proteica do esqueleto colonial, os fósseis de graptólitos são abundantes apenas em rochas sedimentares depositadas em ambientes calmos e anóxicos, como xistos ou calcários negros ricos em matéria orgânica. O colagénio das tecas devia ser destruido em ambientes sedimentares mais oxidados ou turbulentos.

Os graptólitos dendróides formavam colónias de rabdossoma simples que viviam fixas ao fundo do mar. No Ordovícico inferior, estas formas sésseis deram origem aos graptólitos graptolóides planctónicos. Graças ao modo de vida livre, os graptolóides são comuns nos sedimentos do Paleozoico inferior atribuíveis a águas profundas detende, por isso, enorme importância estratigráfica como fósseis de idade. Os gratolóides extinguiram-se mais cedo que os dendróides, no Devónico inferior.

A classe Graptolithina divide-se em seis ordens:

Os graptólitos foram organismos coloniais pertencentes à classe Graptolithina (do grego graptos, escrita + lithos, rocha) do filo Hemichordata, que habitaram os mares do Paleozoico. O grupo surgiu no Câmbrico superior e extinguiu-se no Carbónico inferior (ca. 523 – ca. 330 milhões de anos).

A colónia de graptólitos era constituida por um esqueleto colonial, o rabdossoma, composto por várias cápsulas denominadas tecas que albergavam os organismos indivíduais. As tecas eram compostas de colagénio e uniam-se umas às outras através do nema que suportava a estrutura. Os rabdossomas dos graptólitos podem apresentar uma ou várias estirpes, ou ramos, e são classificados pelos paleontólogos de acordo com a relação geométrica entre estirpes e nema. Devido à natureza proteica do esqueleto colonial, os fósseis de graptólitos são abundantes apenas em rochas sedimentares depositadas em ambientes calmos e anóxicos, como xistos ou calcários negros ricos em matéria orgânica. O colagénio das tecas devia ser destruido em ambientes sedimentares mais oxidados ou turbulentos.

Os graptólitos dendróides formavam colónias de rabdossoma simples que viviam fixas ao fundo do mar. No Ordovícico inferior, estas formas sésseis deram origem aos graptólitos graptolóides planctónicos. Graças ao modo de vida livre, os graptolóides são comuns nos sedimentos do Paleozoico inferior atribuíveis a águas profundas detende, por isso, enorme importância estratigráfica como fósseis de idade. Os gratolóides extinguiram-se mais cedo que os dendróides, no Devónico inferior.

필석(筆石) 또는 그라프톨라이트(Graptolite)는 고생대의 캄브리아기에 나타난 바다 동물의 일종이다. 필석을 논할 때에는 주로 멸종한 종류들을 대상으로 하여 고생대 생물로 인식되지만, 현생 반삭동물 간벽충(Rhabdopleura)을 현재는 필석아강의 일종으로 인정하는 경우가 많아 멸종한 분류라고 단정지을 수는 없다[1][2].

필석 화석은 주로 탄화물질의 얇은 막으로 나온다. 비교적 깊고, 용존산소가 적은 물에서 퇴적된 셰일이나 이암에서 많이 발견된다. 부유성 필석은 물 속을 떠다니기 때문에 분포가 넓고, 또한 종의 분화 속도가 빠르며 화석으로 그 과정이 잘 남기 때문에 표준화석으로 자주 쓰인다. 또한 종류에 따라 먼 바다에 살아 분포가 넓은 종도 있고, 얕은 바다에 살아 분포가 좁은 종도 있다. 이러한 차이가 나는 필석끼리는 시상화석으로도 이용된다.

필석은 마치 산호나 이끼벌레처럼 여러 개체가 껍데기로 덮힌 군집을 이루고 산다. 필석 화석은 이 군집 중에서도 껍데기가 남은 것이다.

군집은 하나의 개체에서 시작하는데, 이 개체의 껍데기를 시큘라(sicula)라고 한다. 시큘라의 오목한 쪽으로 마치 꼬리와 같이 가느다란 구조물이 나기도 하는데, 이는 네마(nema)라고 한다.

시큘라의 개체가 번식하면서 그 주위로 개체들이 하나둘씩 생겨나가고, 군집이 형성된다. 하나의 개체가 자리잡고 있는 껍데기를 포벽(theca, 복수형 thecae)이라고 하고, 포벽들이 나란히 이어져 하나의 줄을 이룰 때 그 줄을 스타이프(stipe)라고 한다[3]. 껍데기 속에 사는 각각의 개체는 일종의 줄기(stolon)로 이어져 있다고 생각된다.

포벽 안에 살고 있는 하나의 필석 개체는 개충(zooid)이라고 불린다. 필석은 일반적으로 껍데기만이 발견되기 때문에 우리가 필석 개충에 대해 아는 것은 얼마 없다.

화석화된 개충은 1978년 Bjerreskov에 의해 최초로 보고되었다. Bjerreskov는 필석 화석에 X선을 쬐어, 황철석이 포벽 주변으로 응집된 것을 발견했다. 그 학자는 이를 개충의 흔적으로 해석하였다[4]. 그 후로 프시그랍투스(Psigraptus)의 황철석으로 치환된 개충이 1984년에 보고되었다. 여기서는 개충과 개충 사이를 잇는 가는 실과 같은 것이 관찰되었는데, 이는 개체들을 연결하는 줄기로 해석되었다[5]. 줄기의 흔적은 이후 라트비아의 실루리아기 필석 화석에서도 보고되었다[6].

이처럼 필석의 개충은 화석으로 남은 기록이 아예 없는 것은 아니다. 그러나 개충의 신체 구조를 일일히 파악할 수 있을 정도로 살아 생전의 모습이 온전하게 보존된 것은 없다[7]. 필석 개충의 모델이나 복원도는 대부분 간벽충을 바탕으로 한 것이 현실이다. 멸종 필석의 경우 포벽, 특히 포벽 입구의 형태가 다양하기 때문에 개충의 형태 역시 다양했으리라고 유추할 수 있다[7].

필석아강에는 여러 하부 분류가 있는데, 그 중 대표적인 분류 두 개는 수지목(혹은 덴드로이드, Dendroidea)과 필석목(혹은 그랍톨로이드, Graptoloidea)이다. 수지목은 부착성 생물로, 캄브리아기에서 석탄기까지 화석이 발견된다. 단, Pseudocallograptus cf. salteri와 같은 일부 종은 별도로 부유성 생활을 터득했다고도 생각된다[2].

필석목은 반대로 물 속을 떠다니는 부유성 생활을 했다. 이들은 오르도비스기에서 데본기까지 화석이 발견된다. 필석목은 수지목 조상으로부터 오르도비스기 초기에 갈라져 나왔는데, 가장 원시적인 필석목인 아니소그랍투스과(Anisograptidae)의 경우 부유성이라고 생각되나 수지목과 유사하게 생겼다. 대체로 나중에 분화되고 번성한 종류일수록 포벽의 형태가 복잡하고, 스타이프의 개수가 적다[3]. 특히 실루리아기와 데본기에 번성한 모노그랍투스과(Monograptidae)의 경우 하나의 스타이프로만 이루어져 있다.