pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

The hide of the Saltwater crocodile is considered very valuable. Many people will pay large amounts of money to have crocodilian products, and Saltwater Crocodile leather products are the most prized. Farms are run for this specific purpose. The crocodile is raised until it is ready to be skinned for leather products. This is a contrversial topic as many people do not find it fit to kill the crocodiles to obtain a small amount of the hide, while the rest of the crocodile is thrown aside.

(Lanworn, 1972)

Although the population of saltwater crocodiles is not stable everywhere, it is in no immediate danger. However, in some countries where the crocodile once thrived, it is now rare or extirpated. Habitat loss associated with coastal development and intensive hunting for hides has drastically reduced populations throughout much of the range. In Sri Lanka and Thailand, habitat destruction is so rapid that the saltwater crocodile has been virtually unseen, with only two saltwater crocodiles being sighted in 1999. In southern Vietnam, where the species once thrived by the thousands, there are but an estimated 100 crocodiles alive in the wild. This is due to the rapid degradation of habitat and the poaching of the animal for leather products. The global population will not be stable until all the countries which have habitats that support the saltwater crocodile have laws that prevent poaching, and programs that create reserves.

A number of such programs have been begun to ensure that C. porosus will not become extinct. In India, a restocking program was introduced in Bhitarkinaka National Park. More than 1,400 saltwater crocodiles were released, with approximately 580 surviving. The population has now become moderately stable at around 1,000 total crocodiles in India. In Burma, crocodile farms are controlling the breeding and conservation of crocodiles. The Australian management program is the world's leader in conservation of the saltwater crocodile. This program focuses its attention on educating the public on precautions to take if they encounter a crocodile, thus discourage unnecessary killing. Crocodile farms were opened to maintain a breeding population, and national sanctuaries have been established, ensuring an undisturbed habitat. Yearly population counts are conducted, monitoring the number of saltwater crocodiles in Australia, making sure that the population does not become dangerously low. In New Papua Guinea, programs that ensure an undisturbed habitat stabilize the population. The Papua New Guinean management system involves a combination of wild cropping, egg and hatchling harvest, and ranching. (Britton, 1995; Carr, 1972)

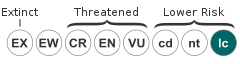

The IUCN rates the species as a whole as "Low Risk." The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service rates the Australian population of this species as "Threatened," does not rate the population in Papua New Guinea, and rates the populations in other countries as "Endangered." Saltwater crocodiles from Australia, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea are included in Appendix II of the CITES treaty, which limits international trade. Members of the species from all other countries are listed in Appendix I, which means they may not be traded internationally.

US Federal List: endangered; threatened

CITES: appendix i; appendix ii

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: lower risk - least concern

The Saltwater Crocodile can be a very dangerous animal to encounter, and humans are attacked and killed by this species every year. Many of these attacks could be prevented by increased awareness and education.

(Britton, 1995)

The Saltwater Crocodile is a predator and has many different types of prey. When young, Crocodylus porosus is restricted to smaller prey like insects, amphibians, crustaceans and small fish and reptiles. When they become an adult, they feed on larger prey such as mud crabs, turtles, snakes, birds, buffalo, wild boar, and monkeys. When the Saltwater Crocodile hunts for food, it usually hides in the water with only the nostrils, eyes, and part of the back exposed. When the prey approaches, it lunges out of the water and attacks, usually killing its prey with a single snap of the jaws. The Saltwater Crocodile then drags the prey under the water where it is more easily consumed.

(Britton, 1995)

Crocodylus porosus is most commonly found on the coasts of northern Australia, and the islands of New Guinea and Indonesia. It ranges west as far as the shores of Sri Lanka and eastern India, all along the shorelines and rivermouths of southeast Asia to central Vietnam, around Borneo and into the Philippines, and even out to Palau, Vanuatu, and the Solomon Islands. Saltwater Crocodiles are strong swimmers and can be found very far from land.

(Britton, 1995; Lanworn, 1972; Carr, 1972)

Biogeographic Regions: oriental (Native ); australian (Native ); indian ocean (Native ); pacific ocean (Native )

The Saltwater Crocodile shows a high tolerance for salinity, being found mostly in coastal waters or around rivers. It may also be found in freshwater rivers, billabongs and swamps.

Movement between habitats occurs during the wet season, when juveniles are raised in freshwater rivers. However, these juveniles are usually forced out of these areas, by dominant males who use the freshwater areas for breeding grounds, and into areas of low salinity. Males who are unable to establish a territory in the river system are either killed or forced out into the sea where they move around the coast in search of another river system.

(Britton, 1995; Pope, 1955)

Terrestrial Biomes: savanna or grassland

Aquatic Biomes: rivers and streams; coastal

Average lifespan

Sex: male

Status: captivity: 41.7 years.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 8.8 years.

Saltwater crocodiles are the largest reptilian species alive today. Adult males can reach up to sizes of 6 to 7 meters. Females are much smaller and do not generally exceed 3 meters, with 2.5 meters considered large. The head is very large and a pair of ridges run from the eyes along the center of the snout. The scales are oval in shape and the scutes are small compared to other species. Young saltwater crocodiles are pale yellow in color with black stripes and spots on the body and tail. This coloration lasts for several years until the crocodile matures into an adult. The color as an adult is much darker, with lighter tan or gray areas. The ventral surface is white or yellow in color. Stripes are present on the lower sides of the body but do not extend onto the belly. The tail is gray with dark bands. Saltwater crocodiles have a heavy set jaw which contains up to 68, and no less than 64, teeth.

Range mass: 1000 to 1200 kg.

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; heterothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: male larger

The Saltwater Crocodile breeds during the wet season which falls between the months of November and March. Despite the fact that the Saltwater Crocodile is normally found in saltwater areas, breeding grounds are established in fresh water. Males mark out their territory and become defensive if another male tries to enter.

Females reach sexual maturity at around 10 to 12 years old. Males, on the other hand, do not reach sexual maturity until the age of 16 years.

The female crocodile normally lays 40 to 60 eggs, but she can lay up to 90 eggs. The eggs are placed in mounded nests made from plant matter and mud and then buried. Since the eggs are laid during the wet season, the nests must be elevated to prevent loss due to floods.

The male does not stay until the eggs are hatched, but the female stays and protects the nest from predators and humans. After incubation for 90 days, the offspring are hatched, although this time varies with nest temperature. Sex determination is directly related to nest temperature. Males are produced around 31.6 degrees Celsius. If this temperature is increased or decreased just a little, females will be produced. The female unearths the eggs when she hears the chirping sounds the offspring make after they hatch. She then assists the offspring into the water by carrying them in her mouth and tends to them until they learn how to swim.

Range number of offspring: 40 to 90.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 10 to 12 years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 16 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; oviparous

Krokodýl mořský (Crocodylus porosus Schneider, 1821), známý také jako krokodýl pobřežní, je největší z dnes žijících krokodýlů a zároveň je dnes největším a nejmohutnějším plazem na světě. Dosahuje délky přes šest metrů a hmotnosti více než jedné tuny. Největší řádně změřený jedinec dosahoval délky 6,3 metru a hmotnosti asi 1,2 tuny, předpokládá se, že výjimečně může dorůst až 7 metrů a vážit okolo 2 tun.[2]

Obývá jižní a jihovýchodní Asii včetně Indonésie a objevuje se až u pobřeží severní Austrálie. Libuje si v mořích s teplejší vodou, nejraději ve vodách Indického a Tichého oceánu mezi Indií a Austrálii. Některé exempláře byly pozorovány na širém moři až tisíc kilometrů od břehů.

Přestože má na zadních končetinách mezi prsty plovací blány, tak je k plavání nepoužívá a plave pomocí vlnění svalnatého ocasu. Je to výborný plavec, udává se, že dokáže uplavat vzdálenost i více než 1000 km po moři. Přesto však nepatří k vysloveně mořským živočichům.[3]

V potravě krokodýl mořský vůbec není vybíravý. Mláďata se zprvu živí hmyzem, měkkýši a pulci. Dospělci loví zvířata od malých krabů a želv přes ryby a obojživelníky až po velké savce. Na kořist útočí bleskurychle z vody, popadne ji (většinou jde po krku) a stáhne do hloubky, kde ji utopí. Krokodýli loví kořist také zespoda ve vodě, to pak útočí na měkké břicho. Pak se do kořisti zakousne svými velkými čelistmi a otáčením z ní rve velké kusy masa. Je to nebezpečný dravec, při útoku dospělého jedince na člověka bývají zranění smrtelná, ročně má na svědomí zhruba 300 lidských životů. Dnes již není na pokraji vyhynutí. Lovci usilují o opětovné povolení lovu. Jeho vzácná kůže se využívá pro výrobu luxusních bot a kabelek. Po mase je poptávka v Asii.

Dospělosti a schopnosti rozmnožování dosahují samice v 10 letech, samci v 16 letech. Samice klade 25 až 60 vajec, která zahrabává asi půl metru hluboko do bahnité půdy ve vzdálenosti asi 50 až 60 metrů od břehu toku nebo nádrže. Na snůšku navrší kupu listí, větví a bahna vysokou téměř metr a v průměru měřící 7 až 9 m. Toto obrovské hnízdo samice hlídá až do vylíhnutí mláďat, ukrytá v louži, kterou si vyhrabe ve vlhké půdě. Mláďata se z vajec zahřívaných tlejícím materiálem líhnou obvykle po dvou měsících (teplota v hnízdě bývá až 32 °C), v nepříznivých podmínkách až po pěti měsících. Matka střeží i vylíhlá mláďata, která měří kolem 25 cm, po několik dní.

Krokodýl mořský (Crocodylus porosus Schneider, 1821), známý také jako krokodýl pobřežní, je největší z dnes žijících krokodýlů a zároveň je dnes největším a nejmohutnějším plazem na světě. Dosahuje délky přes šest metrů a hmotnosti více než jedné tuny. Největší řádně změřený jedinec dosahoval délky 6,3 metru a hmotnosti asi 1,2 tuny, předpokládá se, že výjimečně může dorůst až 7 metrů a vážit okolo 2 tun.

Obývá jižní a jihovýchodní Asii včetně Indonésie a objevuje se až u pobřeží severní Austrálie. Libuje si v mořích s teplejší vodou, nejraději ve vodách Indického a Tichého oceánu mezi Indií a Austrálii. Některé exempláře byly pozorovány na širém moři až tisíc kilometrů od břehů.

Deltakrokodillen (Crocodylus porosus), også kaldet listekrokodillen eller saltvandskrokodillen, er den største af alle nulevende krybdyr og den farligste for mennesker. Den lever i Sydøstasien og i det nordlige Australien.

Voksne hanner er typisk 5 meter lange, men enkelte kan blive 6-7 meter lange og veje mere end 1000 kg. En normal han vejer omkring 450 kg. Hunner er meget mindre end hanner med en længde typisk på 2,5 til 3 meter.

Deltakrokodillen (Crocodylus porosus), også kaldet listekrokodillen eller saltvandskrokodillen, er den største af alle nulevende krybdyr og den farligste for mennesker. Den lever i Sydøstasien og i det nordlige Australien.

Voksne hanner er typisk 5 meter lange, men enkelte kan blive 6-7 meter lange og veje mere end 1000 kg. En normal han vejer omkring 450 kg. Hunner er meget mindre end hanner med en længde typisk på 2,5 til 3 meter.

Das Leistenkrokodil (Crocodylus porosus), auch Salzwasserkrokodil genannt, ist das größte heute lebende Krokodil, gefolgt vom Nilkrokodil. Es handelt sich dabei um eine Art der Echten Krokodile (Crocodylidae). Wie auch die Spitzkrokodile können Leistenkrokodile sowohl im Salz-, als auch im Süßwasser leben. Das Leistenkrokodil ist die am weitesten in den Ozean vordringende Krokodilart, ist aber auch oft in Brackwasser, Flüssen und Sümpfen im Inland zu finden.

Männliche Leistenkrokodile erreichen meist eine Länge von 4,6–5,2 m, die Weibchen bleiben mit 3,1–3,4 m deutlich kleiner.[1] Insbesondere in durch menschlichen Einfluss angeschlagenen Populationen sind solche Maße bereits selten: Im Bentota Ganga (Sri Lanka) beobachtete Gramentz (2008) von 16 Exemplaren nur ein Exemplar von mehr als 2,5 m Länge.[2] Eine andere Studie untersuchte Leistenkrokodile aus Palau – keines von ihnen war größer als 3,3 m.[3] Oft werden für Leistenkrokodile Maximallängen deutlich über diesen Maßen genannt; praktisch sind jedoch fast nie Körperteile solcher Krokodile als Beweise überliefert. Angeblich erlegte ein Jäger in den 1950er Jahren ein Krokodil, das 8,5 m maß. Webb & Manolis (1989) halten diesen Rekord für die verlässlichste Rekordlänge.[1] Ein männliches Exemplar mit 6,17 m zumindest ist in jüngerer Zeit verbürgt.[4] 4 m lange Leistenkrokodile wiegen im Schnitt 240 kg,[1] extrem große Exemplare können rund 1 t wiegen.[5]

Der Körper ist sehr breit mit einer großen und breit ausgebildeten Schnauze, wodurch man es vom Gangesgavial und dem Australien-Krokodil gut unterscheiden kann. Von den Augen laufen zwei erhöht liegende Grate (Leisten) zur Mitte der Schnauze, die dem Leistenkrokodil seinen deutschen Namen gaben. Die ausgewachsenen Tiere sind grau bis graubraun oder goldbraun, es sind jedoch auch völlig schwarze (Melanismus) und weiße (Albinismus) Exemplare bekannt. Die Jungtiere sind heller und besitzen eine dunkle Zeichnung aus Flecken und Querbändern, die viele Tiere im Laufe des Alterns verlieren. Die Panzerung des Rückens ist sehr gleichmäßig und die Form der Einzelschuppen ist oval. Eine Panzerung direkt hinter dem Kopf fehlt. An Bauch und Schnauze besitzen sie Sinneszellen, mit denen Vibrationen des Wassers wahrgenommen werden können.

Detailansichten:

Das Verbreitungsgebiet ist sehr groß. Es reicht von Ostindien über Südostasien bis nach Nordaustralien und umfasst die gesamte ozeanische Inselwelt. Der genaue Umfang dieser Verbreitung ist noch nicht abschließend geklärt, selbst auf den Palauinseln,[3] den Kokosinseln, den Neuen Hebriden und auf Fidschi wurden diese Krokodile gesichtet. Bis Anfang des 19. Jahrhunderts kamen Leistenkrokodile auch im westlichen Indischen Ozean auf den Seychellen und auf Aldabra vor.[7] Damit ist es das Krokodil mit dem größten Verbreitungsgebiet überhaupt. Mit verantwortlich dafür ist sicher die „Reichweite“ der Art: es wurden Exemplare 1000 km vom Land entfernt auf hoher See gesehen. Ein Männchen der Spezies legte 1400 km von Palau bis nach Pohnpei in Mikronesien zurück. An manchen Vertretern dieser Art wurden sogar Seepocken gefunden, die ansonsten nur bei pelagischen Meerestieren gefunden werden.

Der eigentliche Lebensraum des Leistenkrokodils sind Flussmündungen und Mangrovensümpfe. Dabei handelt es sich meist um Brackwasserzonen; es dringt jedoch auch weit in Süßwasserflüsse ein und kann auch in großen Seen und Sümpfen im Landesinneren angetroffen werden.

Junge Leistenkrokodile ernähren sich vor allem von Insekten und kleinen Amphibien. Mit zunehmender Körpergröße werden vor allem Fische und Wasserschildkröten, aber auch Säugetiere und Vögel aller Art gefressen. Möglicherweise werden auch noch andere kleinere Krokodile wie das Siam-Krokodil erbeutet. Kannibalismus kommt öfter vor: Bei einer Leistenkrokodilpopulation nahe Darwin wurde beobachtet, wie sich die Population zunächst erholte, als die Jagd auf sie eingestellt wurde. Im zweiten Jahr sank die Population wieder, da die Jungtiere des ersten Jahres anfingen, die neue Generation zu fressen.

Leistenkrokodile verwenden mehrere Methoden, um ihre Beute zu erlegen:

Leistenkrokodile können bis zu einem Jahr ohne Nahrung leben und sich dabei nur von den Fettreserven in ihrem Schwanz versorgen. Diese Fähigkeit – wie auch ihre Ausdauer beim Durchqueren der Ozeane – verdanken sie ihrem extrem regulierbaren Stoffwechsel. Benötigen Säugetiere bis zu 80 Prozent ihrer Nahrung zur Aufrechterhaltung ihrer Körpertemperatur, kommen Krokodile mit zehn Prozent aus. Das Tier kann mit heruntergefahrenen Stoffwechsel auch einige Monate ohne Wasser überleben. Dazu gräbt es sich im Schlamm der letzten verbliebenen Wasserlöcher ein oder zieht sich in kühle Höhlen zurück.

Beim Tauchen machen Leistenkrokodile sich den von steigendem Umgebungsdruck und veränderten Sauerstoff- und Kohlendioxidanteilen im Blut ausgelösten Tauchreflex zunutze. Von Rezeptoren in der Nase, der Oberlippe, im Kiefer und der Zunge empfängt der Parasympathikus Reize, die bewirken, dass die Tiere ihren Puls auf zwei Herzschläge in drei Minuten senken können. Auf diese Weise können sie bis zu einer Stunde tauchen.[9]

Die Weibchen des Leistenkrokodils werden mit zehn Jahren geschlechtsreif, während Männchen im Alter von etwa 16 Jahren die Geschlechtsreife erreichen. Zu Anfang der Paarungszeit brüllen die Männchen, um Weibchen anzulocken, machen dies aber nicht so oft wie der Mississippi-Alligator, da sie in offener Landschaft leben. Das Territorialverhalten der Männchen steigt in dieser Zeit. Nach der Paarung verteidigt das Männchen das Revier weiterhin stark. Zur Fortpflanzungszeit in der feuchten Jahreszeit wird ein Hügelnest aus Pflanzenmaterialien gebaut, das eine Höhe von 30 bis 80 Zentimeter und einen Durchmesser von 120 bis 250 Zentimeter haben kann. Ein solches Nest umfasst 60 bis 80 Eier und wird bis zum Schlupf der Jungen bewacht. Durch die verrottenden Pflanzen entsteht Fäulniswärme, die das Ausbrüten der Eier beschleunigt.[10] Häufig wurde eine Brutfürsorge von bis zu drei Monaten beobachtet. Wenn die Jungen geschlüpft sind, wachen die Krokodile acht Wochen über ihre Brut, deren nahezu 70%ige Überlebenschance ebenfalls eine Ausnahme darstellt.

Die maximale Lebenserwartung von Leistenkrokodilen beträgt über 70 Jahre.

Jungtiere haben viele Feinde, zum Beispiel Störche, Greifvögel, große Fische und größere Artgenossen. Wenn Leistenkrokodile ausgewachsen sind, haben sie kaum noch natürliche Feinde. Manchmal werden kleine bis mittelgroße Krokodile von großen Pythons oder Tigern erbeutet. Des Weiteren wird Krokodilfleisch auch von Menschen verzehrt.

Im nördlichen Australien kommt es etwa zweimal pro Jahr zu einem belegten Krokodilangriff. Zwischen 1971 und 2004 wurden 62 unprovozierte Angriffe registriert, die in 17 Fällen tödlich verliefen.[11] So wurde zum Beispiel 2002 eine deutsche Touristin beim Baden im Kakadu-Nationalpark getötet.[12] Um solche Attacken zu vermeiden, werden Leistenkrokodile von Wildhütern an Badeplätzen eingefangen und fortgebracht. Zudem wird versucht, Badestrände mit Netzen zu schützen. Besonders aggressive Krokodile, die mehrfach angegriffen haben, werden als „rogue crocodiles“ („Schurken-Krokodile“) bezeichnet. Das wohl bekannteste „rogue crocodile“ war Sweetheart, das zwischen 1971 und 1979 15 Fischerboote schwer beschädigte, allerdings die Insassen weitgehend ignorierte und niemanden verletzte.

Im Rahmen des Pazifikkrieges 1941–1945 kam es angeblich zu einem tödlichen Desaster: Im Februar 1945 landeten englisch/indische Kampftruppen auf den noch von den Japanern besetzten Ramree-Inseln vor der Südküste Burmas. Ein Kapitulationsangebot lehnte der japanische Kommandant ab und beschloss mit seiner Truppe von ca. 1000 Mann den nächtlichen Ausbruch aus der Umzingelung quer durch die ausgedehnten Mangrovensümpfe zum offenen Meer. Dieser Entschluss sollte sich als fatal erweisen und endete in einer Katastrophe. In den Mangrovensümpfen lauerten Hunderte von Leistenkrokodilen, die ein Massaker unter den fliehenden Japanern angerichtet haben sollen. Lediglich 20 Japaner, die sich am nächsten Morgen den Engländern ergaben, hatten die Nacht überlebt. Im Guinness-Buch der Rekorde wird das Ereignis als größtes Desaster, das Tiere (hier: Leistenkrokodile) unter Menschen jemals angerichtet haben, geführt. Allerdings wird die Korrektheit dieser Darstellung bestritten und von anderen Autoren als ein moderner Mythos („urban legends“) bezeichnet, da es keinen wirklichen Nachweis für die Historizität des Vorfalls gibt.[13] Insbesondere finden sich keine Hinweise in den britischen Militärberichten und keiner der befragten japanischen und lokalen Zeitzeugen konnte den Vorfall bestätigen.[14]

Der Bestand an Leistenkrokodilen verringerte sich in den 1950er und 1960er Jahren, weil ihre Haut für die Lederproduktion geeignet ist und sie deswegen stark bejagt wurden.[15] Vor 20 Jahren erholte sich der Bestand wieder, da sie ihren Lebensraum weitgehend unberührt wieder aufgefunden haben.[16] Seit Leistenkrokodile durch das Washingtoner Artenschutzabkommen von 1973 geschützt sind, werden sie in Farmen für die Lederproduktion gezüchtet; das Fleisch wird in Australien als Nahrungsmittel verkauft.

Als Touristenattraktion dienen sie unter anderem am Adelaide River nahe Darwin im australischen Northern Territory: Von einem großen Boot aus werden Fleischstücke an einer Angel über das Wasser gehalten: Die Leistenkrokodile (Jumping Crocodiles) springen dann bis zu einigen Metern Höhe aus dem Wasser und schnappen sich die Fleischbrocken (siehe Foto). Weltweit bekannt wurden die Leistenkrokodile durch die Filme der Crocodile-Dundee-Serie.

In Osttimor wird das Leistenkrokodil als „Großvater Krokodil“ verehrt. Ursprung dafür ist die Legende des guten Krokodils, nach der die Insel Timor aus einem Krokodil entstanden ist. Seitdem die Jagd auf die Krokodile nach Abzug der indonesischen Besatzung eingestellt wurde, haben die Krokodilangriffe rapide zugenommen. CrocBITE, die Datenbank für Krokodilangriffe der Charles Darwin University, registrierte seit 2007 (Stand: Sep. 2016) 15 tödliche und fünf weitere Attacken in Osttimor, einem Land von der Größe Schleswig-Holsteins und mit etwas mehr als einer Million Einwohnern.[17]

Die Datenbank registrierte seit 1995 insgesamt 1024 Angriffe von Leistenkrokodilen auf Menschen, 591 davon tödlich. Etwa die Hälfte aller Krokodilattacken weltweit geht auf das Konto von Leistenkrokodilen. Das an zweiter Stelle stehende Nilkrokodil verursacht nur ein Viertel aller weltweiten Vorfälle, bei denen aber zwei Drittel tödlich für das Opfer endeten.[17]

Das Tier dient als Motiv für eine Anlagemünze aus Silber, das Australian Saltwater Crocodile, die 2014 von der australischen Prägeanstalt Perth Mint ausgegeben wurde, und für ähnliche Sammlermünzen des gleichen Herausgebers.

Warnschild an einem Fähranleger in Queensland (Australien)

Leistenkrokodil Max (1956–2015) im Zoo Dresden

Das Leistenkrokodil (Crocodylus porosus), auch Salzwasserkrokodil genannt, ist das größte heute lebende Krokodil, gefolgt vom Nilkrokodil. Es handelt sich dabei um eine Art der Echten Krokodile (Crocodylidae). Wie auch die Spitzkrokodile können Leistenkrokodile sowohl im Salz-, als auch im Süßwasser leben. Das Leistenkrokodil ist die am weitesten in den Ozean vordringende Krokodilart, ist aber auch oft in Brackwasser, Flüssen und Sümpfen im Inland zu finden.

Aɣucaf awlal (assaɣ usnan: Crocodylus porosus) d yiwen n uɣucaf ameqran imi d netta yakk id ameqran deg twacult n temraradin, Yettidir deg waṭas n yedgan, Seg ugafa n Ustṛalya ar uneẓel n usamar n Asya ar teftist tasamrant n Lhend

Aɣucaf awlal (assaɣ usnan: Crocodylus porosus) d yiwen n uɣucaf ameqran imi d netta yakk id ameqran deg twacult n temraradin, Yettidir deg waṭas n yedgan, Seg ugafa n Ustṛalya ar uneẓel n usamar n Asya ar teftist tasamrant n Lhend

Cirnîsa avê şor an tîmsahê Hindî (Crocodylus porosus), cureyekî cirnîsan (Crocodylus) e. Cirnîsê avê şor, ew bi rastî xijendeyê tewr girs û mestir ser rû yê erdê ku ta niha mayî ye.

Mezinahiya nêrê cirnîsê avê şor dighêje 7 m û bi dirêjî û 2000 kg bi giranî ye.[2]

Cirnîsa avê şor an tîmsahê Hindî (Crocodylus porosus), cureyekî cirnîsan (Crocodylus) e. Cirnîsê avê şor, ew bi rastî xijendeyê tewr girs û mestir ser rû yê erdê ku ta niha mayî ye.

Crocodylus porosus es un specie de Crocodylus.

Kiâm-chúi kho̍k-hî (Eng-gí miâ: saltwater crocodile; ha̍k-miâ: Crocodylus porosus) sī thong sè-kài siāng hêng-thé siāng toā ê kho̍k-hî, mā sī hiān-chûn siāng toā ê pâ-thiông-lūi tōng-bu̍t. In seng-oa̍h tī Lâm-iûⁿ kap Ìn-tō͘ tang hái-hoāⁿ kiam Australia pak hái-hoāⁿ. In ū-sî mā ē tùi hái-liû lâu khi pia̍t-ūi..

The sautwatter crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), an aa kent as the estuarine crocodile, Indo-Paceefic crocodile, marine crocodile, sea crocodile or informally as sautie,[2] is the lairgest o aw livin reptiles, as well as the lairgest riparian predator in the warld.

The sautwatter crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), an aa kent as the estuarine crocodile, Indo-Paceefic crocodile, marine crocodile, sea crocodile or informally as sautie, is the lairgest o aw livin reptiles, as well as the lairgest riparian predator in the warld.

Морскиот крокодил (Crocodylus porosus) е најголемиот од сите преживеани видови на крокодиловидни животни и рептили. Го среќаваме низ Југоисточна Азија, Северна Австралија и околните води.

Морскиот крокодил има подолга муцка од индискиот крокодил, и е двапати подолг во ширина [1].

Возрасен мажјак од морскиот крокодил најчесто расте помеѓу 4,9 и 5,5 метри и тежи од 640 до 1100 килограми [2]. Женките се помали од мажјаците (види полов диморфизам) и достигнуваат должина помеѓу 2,1 и 3 метри [3][4]. Најголемата регистрирана женка била со должина од 4,2 метри [5]. Морскиот крокодил има помалку коскени израстоци на вратот од останатите видови на крокодили и неговото широко тело е исто така поразлично од останатите, поради што на почетокот имало претпоставки дека се работи за алигатор [3].

Максималната големина која овие крокодили можат да ја достигнат е тема на бројни контроверзии. Најдолгиот крокодил некогаш измерен од муцката до опашката и проверен преку мерење на неговата кожа, бил долг 6,2 метри. Бидејќи кожите имаат тенденција да се смалат откако ќе се одвојат од месото, должината на крокодилот кога бил жив е проценета на 6,3 метри, и се претпоставува дека тежел околу 1200 килограми [6]. Нецелосни останки (череп на крокодил убиен во Ориса [7]) се декларирани дека се од крокодил дол 7,6 метри, но после експертската анализа на черепот заклучено е дека припаѓал на крокодил не подолг од 7 метри [6]. Има и бројни декларации за крокодили кои надминувале 9 метри, сепак анализата на черепите покажала дека убиените животни биле со должина помеѓу 6 и 6,6 метри [5].

Денес со обновата на живеалиштето на морскиот крокодил и со намалениот лов, можно е да има индивидуи со должина од 7 метри или повеќе [8]. Гинис прифатил тврдење за 7 метарски мажјак од морски крокодил, со проценета тежина од 2000 килограми, кој живее во паркот Бхитарканика во државата Ориса, Индија [7][9]. Сепак поради невозможната мисија за фаќање и мерење на толку голем жив крокодил, нековите димензии никогаш не биле прецизно измерени.

Еден крокодил убиен во Квинсленд во 1957 година бил пријавен со должина од 8,5 метри, но никогаш не се направени мерења за проверка, и не постојат било какви останки од овој крокодил. Реплика на овој крокодил е направена како туристичка атракција [10][11][12]. Постојат и многу други пријави за крокодили кои надминуваат 8 метри [13][14] меѓутоа овие се многу сомнителни и непроверени [6].

Морските крокодили се со намален број во повеќето региони и се смета дека се скоро изумрени во Тајланд (можно е да има неколку индивидуи во националните паркови) и Виетнам (со исклучок на повремени „доселеници“ од Камбоџа). Во Камбоџа постојат мал број на крокодили кои живеат во реките и мочуриштата. Статусот и бројноста на морските крокодили во Мијанмар е непознат, а се знае дека постојат во Бангладеш. Иако морските крокодили некогаш биле доста чести во делтата на Меконг (каде изумреле во 1980тите) и многу други речни системи, денес иднината на овие животни во југоисточна Азија не е многу светла. Сепак, опасноста од изумирање на овој вид е многу мала, поради неговата голема глобална распространетост и огромните популации во Северна Австралија и Нова Гвинеја. Во Индија е доста редок во повеќето региони, но е доста присутен во северо-источниот дел на земјата, односно во Ориса и Сундербанс. Постојат спорадични популации низ Индонезија и Малезија, каде во одредени делови постојат огромни популации (Борнео на пример), додека во други делови популациите се во опасност од изумирање (Филипини). Морскиот крокодил исто така е присутен и во одредени делови на јужниот Пацифик, со средна популација на Соломоновите острови, мала популација на Винуату (се претпоставува дека ќе исчезне во блиска иднина, бидејќи брои 3 индивидуи), и популација со солиден број индивидуи но под ризик на Палау [3]. Во северна Австралија (каде спаѓаат делови на Северна Територија, Западна Австралија и Квинсленд) популацијата на морски крокодили константно се зајакнува. Во овие региони се среќаваат и огромни индивидуи кои надминуваат 6 метри. Според груба проценка популацијата на Австралиски морски крокодил брои 100 000 – 200 000 индивидуи. Распространети се од Брум во Западна Австралија, преку целата Северна Територија, па се до Рокхамптон во Квинсленд. Овој вид многу често се среќава и во Нова Гвинеја, каде живее во крајбрежните води, некои речни системи, делти и мочуришта.

Морските крокодили некогаш го населувале и источниот брег на Африка и Сејшелските острови. Овие крокодили се верувало дека спаѓаат во видот на нилскиот крокодил, но потоа се докажало дека всушност се Crocodylus porosus [3].

Морските крокодили за време на тропската дождовна сезона ги населуваат слатководните мочуришта и реки, а за време на сувата сезона мигрираат кон делтите на реките и понекогаш навлегуваат во морето. Крокодилите жестоко се борат меѓу себе за територија, и доминантните мажјаци ги завземаат најдобрите простори од слатководните реки и потоци. Младите крокодили се приморани да живеат во маргиналните делови на речните системи, а понекогаш дури и во океанот. Ова ја објаснува огромната распространетост на овој вид крокодил (од источниот брег на Индија до северна Австралија), и фактот што понекогаш го среќаваме и на многу невообичаени места како Јапонското Море.

Морскиот крокодил е опортунистички предатор кој е способен да го улови било кое животно кое ќе навлезе на негова територија, без разлика дали на копно или во вода. Познато е дека овие крокодили напаѓаат и луѓе. Младите крокодили напаѓаат помали животни како инсекти, водоземци, ракови, мали рептили и риби. Колку крокодилот расте поголем, така расте и листата на животни кои се вклучени во неговата исхрана. Сепак поголем дел од нивната исхрана ја сочинуваат мали животни. Морските крокодили можат да се хранат со мајмуни, кенгури, диви свињи, динго, птици, гоани, домашна стока, воден бивол, гаури, ајкули [15][16] или луѓе [17][8], како и многу други животни. Домашната крава, коњ, вдниот бивол и гаурот, кои можат да тежат над тон, се сметаат за најголемиот плен кој може да биде уловен од мажјак морски крокодил. Единствена закана за возрасен морски крокодил претставуваат другите крокодили [5].

Генерално овие крокодили делуваат незаинтересирано – карактеристика која им овозможува да преживеат месеци кога нема храна. Најчесто овие крокодили го поминуваат денот безделничејќи во вода или сончајќи се на брегот, а ловат за време на ноќта. Кога напаѓаат, изведувааат многу брзи движења, без разлика дали напаѓаат на копно или од вода.

Бидејќи е предатор кој напаѓа од заседа, крокодилот најчесто чека пленот да се доближи до водата пред да нападне. Повеќето животни се усмртени од огромната сила на вилиците, додека некои се дават откако крокодилот ќе го одвлече пленот во вода. Морскиот крокодил е многу силно животно и без пролем може да одвлече во вода возрасно водно бафало.

Во неговиот најопасен напад, наречен „смртоносно превртување“, крокодилот го грабнува животното и се превртува. Ова е со цел да го го исфрли животното од рамнотежа со што може полесно да го одвлечка во водата. Ова движење го употребува и да растргнува веќе мртви големи животни.

Иако морските крокодили се многу опасни животни, сепак нападите на луѓе не се толку чести. Повеќето напади од возрасен крокодил се фатални, со оглед на големината и силата на ова животно. Во Австралија, нападите се доста ретки. Има не повеќе од 1-2 пријавени напади годишно во земјата [18]. Ниското ниво на напади, најверојатно се должи на многубројните предупредувања поставени од властите во близина на речиси секое мочуриште, река, езеро, па дури и на некои плажи, како и добрата информираност на населението. Во абориџинската заедница од Арнхемленд, која завзема одприлика половина од северниот дел на Северната Територија, можно е да има повеќе непријавени напади од крокодили. Во останатите делови каде што морскиот крокодил е распространет и каде не се превземени безбедносни мерки како во Австралија, бројот на напади е и до неколку илјади годишно. Најголемиот број од овие „непријавени“ напади се во Нова Гвинеја каде има огромни популации од овој вид. Регистрирани се и напади во Борнео, Суматра и Мијанмар.

Доктор Адам Бритон ја проучува интелигенцијата кај крокодиловидните животни. Тој тврди дека иако крокодилскиот мозок е доста помал од тој на цицачите (околу 0,05% од телесната тежина кај морскиот крокодил), овие животни се способни да учат тешки задачи. Тој укажува дека морските крокодили се паметни животни и дека најверојатно можат да учат многу побрзо од лабораториските глувци. Докажано е дека овие крокодили се способни да ја научат миграциската патека на нивниот плен за време на климатските промени.

Морскиот крокодил (Crocodylus porosus) е најголемиот од сите преживеани видови на крокодиловидни животни и рептили. Го среќаваме низ Југоисточна Азија, Северна Австралија и околните води.

खारे पानी का मगरमच्छ या एस्टूएराइन क्रोकोडाइल (estuarine crocodile) (क्रोकोडिलस पोरोसस) सबसे बड़े आकार का जीवित सरीसृप है। यह उत्तरी ऑस्ट्रेलिया, भारत के पूर्वी तट और दक्षिण-पूर्वी एशिया के उपयुक्त आवास स्थानों में पाया जाता है।

खारे पानी के मगरमच्छ की थूथन, मगर कहलाने वाले मगरमच्छ से अधिक लम्बी होती है: आधार पर इसकी लम्बाई चौड़ाई से दोगुनी होती है।[1] अन्य प्रकार के मगरमच्छों की तुलना में, खारे पानी के मगरमच्छ की गर्दन पर कवच प्लेटों की संख्या कम होती है और अधिकांश अन्य पतले शरीर के मगरमच्छों की तुलना में इसके शरीर का चौड़ा होना, इस असत्यापित मान्यता को जन्म देता है की सरीसृप एक एलीगेटर (घड़ियाल) था।[2]

एक वयस्क नर खारे पानी के मगरमच्छ का भार 600 से 1,000 किलोग्राम (1,300–2,200 पौंड) और लम्बाई सामान्यतया 4.1 से 5.5 मीटर (13–18 फीट) होती है। हालांकि परिपक्व नर की लम्बाई 6 मीटर (20 फीट) या अधिक और भार 1,300 किलोग्राम (2,900 पौंड) या अधिक भी हो सकता है।[3][4][5] किसी अन्य आधुनिक मगरमच्छ प्रजाति की तुलना में, इस प्रजाति में लैंगिक द्विरुपता सबसे अधिक देखने को मिलती है, इनमें मादा नर की तुलना में काफी छोटे आकार की होती है। एक प्रारूपिक मादा के शरीर के लम्बाई 2.1 से 3.5 मीटर (7–11 फीट) की रेंज में होती है।[2][3][6] अब तक दर्ज की गयी सबसे बड़े आकार की मादा की लम्बाई लगभग 4.2 मीटर (14 फीट) नापी गयी है।[5] पूरी प्रजाति का औसत भार मोटे तौर पर 450 किलोग्राम (1,000 पौंड) है।[7]

खारे पानी के मगरमच्छ का सबसे बड़ा आकार काफी विवाद का विषय है। अब तक थूथन से लेकर पूंछ तक मापी गयी सबसे लम्बे मगरमच्छ की लम्बाई 6.1 मीटर (20 फीट) थी, जो वास्तव में एक मृत मगरमच्छ की त्वचा थी।

चूंकि मृत त्वचा की परत के हटाये जाने के बाद (carcass) त्वचा थोड़ी सी सिकुड़ जाती है, इसलिए जीवित अवस्था में इस मगरमच्छ की अनुमानित लम्बाई 6.3 मीटर (21 फीट) रही होगी और संभवतया इसका वजन 1,200 किलोग्राम (2,600 पौंड) से अधिक रहा होगा। [8] ऐसा दावा किया गया है कि अधूरे अवशेष (उड़ीसा में शूट किये गए एक मगरमच्छ की खोपड़ी[9]) एक 7.6-मीटर (25 फीट) मगरमच्छ के हैं, परन्तु विशेषज्ञों के द्वारा किये गए परीक्षण बताते हैं कि इसकी लम्बाई 7 मीटर (23 फीट) से अधिक नहीं होगी। [8] 9-मीटर (30 फीट) की रेंज में मगरमच्छों के असंख्य दावे किये गए हैं: बंगाल की खाड़ी में 1940 में शूट किये गए एक मगरमच्छ को 10 मीटर (33 फीट) पर दर्ज किया गया; एक और मगरमच्छ को 1823 में फिलिपिन्स में ल्युज़ोन के प्रमुख द्वीप पर जलजला में मारा गया, इसे 8.2 मीटर (27 फीट) पर दर्ज किया गया; 7.6 मीटर (25 फीट) पर दर्ज किये गए एक मगरमच्छ को कलकत्ता के अलीपुर जिले में हुगली नदी में मारा गया। हालांकि, इन जानवरों की खोपड़ियों के परीक्षण वास्तव में इंगित करते हैं कि ये जानवर 6 से 6.6 मीटर (20–22 फीट) की रेंज से थे।

हाल ही में खारे पानी के मगरमच्छ के आवास की बहाली और शिकार को कम किये जाने के कारण, यह संभव हो पाया है कि 7-मीटर (23 फीट) मगरमच्छ आज जीवित हैं।[10] गिनीज ने इस दावे को स्वीकार किया है कि एक 7-मीटर (23 फीट) नर खारे पानी का मगरमच्छ भारत के उड़ीसा राज्य में भीतरकनिका पार्क में रहता है,[9][11] हालांकि, एक बहुत बड़े आकार के जीवित मगरमच्छ को पकड़ने और इसके मापन में होने वाली कठिनाई के कारण, इन आयामों की सटीकता का सत्यापन अब तक किया जाना बाकी है।

1957 में क्वींसलैंड में शूट किये गए एक मगरमच्छ की लम्बाई 8.5 मीटर (28 फीट) थी, लेकिन इस माप को सत्यापित नहीं किया गया और ना ही इस मगरमच्छ के कोई अवशेष अब मौजूद हैं। इस मगरमच्छ की एक "प्रतिकृति" बनाई गयी है जो पर्यटकों के आकर्षण का केंद्र बन गयी है।[12][13][14]

8 मीटर से अधिक लम्बे (28 फीट से लम्बे) कई मगरमच्छों को भी दर्ज किया गया है लेकिन इनकी पुष्टि नहीं हुई है,[15][16] और इनकी संभावना अत्यधिक कम है।

खारे पानी का मगरमच्छ भारत में पाई जाने वाली मगरमच्छ की तीन प्रजातियों में से एक है, इसके अलावा मगर कहे जाने मगरमच्छ और घड़ियाल पाए जाते हैं।[17]

भारत के पूर्वी तट के अलावा, यह मगरमच्छ भारतीय उपमहाद्वीप में अत्यंत दुर्लभ है। खारे पानी के मगरमच्छों की एक बड़ी आबादी (इनमें कई बड़े आकार के व्यस्क हैं, एक 7 मीटर की लम्बाई का नर भी शामिल है) उड़ीसा के भीतरकनिका वन्यजीव अभयारण्य में मौजूद है और ये सुंदरवन के भारतीय और बांग्लादेश के हिस्सों में कम संख्या में पाए जाते हैं।

उत्तरी ऑस्ट्रेलिया में (जिसमें उत्तरी क्षेत्र के उत्तरी हिस्से, पश्चिमी ऑस्ट्रेलिया और क्वीन्सलैंड शामिल हैं) खारे पानी के मगरमच्छ संख्या में खूब बढ़ रहें हैं, विशेष रूप से डार्विन के पास बहुल नदी प्रणाली में (जैसे एडिलेड, मेरी और डेली नदियां और इनके साथ इनसे जुडी हुई नदशाखाएं और ज्वारनदमुख) जहां बड़े आकार के जीव (6 मीटर से अधिक) आम हैं। ऑस्ट्रेलियाई खारे पानी के मगरमच्छों की आबादी अनुमानतः 100,000 और 200,000 वयस्कों के बीच है।

ये पूरे उत्तर क्षेत्री तट में पश्चिमी ऑस्ट्रेलिया में ब्रूम से लेकर क्वीन्सलैंड में नीचे रॉकहैम्प्टन तक फैले हुए हैं। ताजे पानी में पाए जाने वाले मगरमच्छों की तुलना में खारे पानी के मगरमच्छों के एलीगेटर से मिलते जुलते होने के कारण, उत्तरी ऑस्ट्रेलिया की एलीगेटर नदियों का नाम बदल गया है। ताजे पानी के मगरमच्छ उत्तरी क्षेत्र में भी रहते हैं।न्यू गिनी में भी वे आम हैं, जो सभी ज्वारनदमुख और मैंग्रोव सहित देश में लगभग सभी नदी प्रणालियों के तटीय क्षेत्रों में पाए जाते हैं। वे बिस्मार्क द्वीपसमूह, काई द्वीप, आरू द्वीप, मालुकु द्वीप और तिमोर क्षेत्र में आने वाले द्वीपों और टोरेस स्ट्रेट के भीतर अधिकांश द्वीपों में भी अलग अलग संख्या में पाए जाते हैं।

खारे पानी का मगरमच्छ ऐतिहासिक रूप से पूरे दक्षिण पूर्वी एशिया में पाया गया, लेकिन अब इस रेंज में से विलुप्त हो चुका है। इस प्रजाति को इंडोचाईना के अधिकांश भागों में दशकों से जंगलों में दर्ज नहीं किया गया है और थाईलैंड, लाओस, वियतनाम और संभवतः कम्बोडिया में यह विलुप्त हो चुकी है। म्यांमार एक अधिकांश हिसों में इस प्रजाति की स्थिति जटिल है, लेकिन इर्रवाड्डी डेल्टा में कई बड़े आकार के वयस्कों की एक स्थिर आबादी है।[18] यह संभव है कि म्यांमार इंडोचाइना में एकमात्र देश है जहां आज भी इस प्रजाति की जंगली आबादी मौजूद है। हालांकि एक समय था जब मेकोंग डेल्टा (जहां से वे 1980 के दशक में गायब हो गए) और अन्य नदी प्रणालियों में खारे पानी के मगरमच्छ बहुत आम थे, इंडोचाइना में इस प्रजाति का भविष्य खतरे में नज़र आ रहा है। हालांकि, इस बात की संभावना भी बहुत कम है कि मगरमच्छ पुरी दुनिया से विलुप्त हो जाये, क्योंकि इसका वितरण व्यापक है और उत्तरी ऑस्ट्रेलिया तथा न्यू गिनी में इसकी आबादी का आकार पूर्व-औपनिवेशिक प्रकार का है।

इंडोनेशिया और मलेशिया में इसकी आबादी छिटपुट है, जबकि कुछ क्षेत्रों में अधिक आबादी भी है (जैसे बोर्नियो) और कई अन्य स्थानों पर इसकी आबादी बहुत कम है, जो जोखिम (विलुप्त होने के कगार पर) पर है, (उदाहरण फिलिपीन्स). सुमात्रा और जावा में इस प्रजाति की स्थिति बड़े पैमाने पर अज्ञात है (हालांकि समाचार एजेंसियों और विश्वसनीय स्रोतों के द्वारा सुमात्रा के पृथक्कृत क्षेत्रों में बड़े मगरमच्छों के द्वारा मनुष्यों पर हमला किये जाने की रिपोर्टें हाल ही में दर्ज की गयी हैं).उत्तरी ऑस्ट्रेलिया के आस पास मगरमच्छों के पाए जाने के बावजूद, बाली में अब मगरमच्छ नहीं बचे हैं। खारे पानी का मगरमच्छ दक्षिण प्रशांत के बहुत सीमित हिस्से में भी पाया जाता है, सोलोमन द्वीप में इसकी आबादी औसत है, वानुअतु (जहां आबादी अधिकारिक तौर पर केवल तीन रह गयी है) में इसकी आबादी बहुत कम, आक्रामक और जल्दी ही विलुप्त होने वाली है और पलाऊ में यह आबादी आक्रामक नहीं है, परन्तु जोखिम पर है (जिसके बढ़ जाने की संभावना है).एक समय था जब खारे पानी के मगरमच्छ सेशेल्स द्वीप में अफ्रीका के उत्तरी तट से लेकर पश्चिम तक पाए जाते थे। ऐसा माना जाता था कि ये मगरमच्छ नील नदी की आबादी हैं, लेकिन बाद में यह प्रमाणित हो गया कि वे ये क्रोकोडिलस पोरोसस हैं।[2]

क्योंकि समुद्र में लम्बी दूरी की यात्रा करना इस प्रजाति की प्रवृति है, इसलिए कभी कभी ये मगरमच्छ ऐसे अजीब स्थानों पर भी देखे जाते हैं, जहां के वे स्थानीय निवासी नहीं हैं। आवार किस्म के जीव भी ऐतिहासिक रूप से न्यू कैलेडोनिया, लवो जिमा, फिजी और यहां तक कि जापान के अपेक्षाकृत उदासीन समुद्र (उनके स्थानीय आवास स्थान से हजारों मील दूर) में भी पाए गए हैं। 2008 के दशक के अंत /2009 के दशक के प्रारंभ में फ्रेजर द्वीप की नदी प्रणाली में कई वन्य खारे पानी के मगरमच्छ पाए गए, इन्हें इनकी सामान्य क्वीन्सलैंड रेंज से हजारों किलोमीटर दूर अधिक ठन्डे पानी में पाया गया। ऐसा पाया गया कि वास्तव में ये मगरमच्छ गर्म और नम मौसम के दौरान उत्तरी क्वीन्सलैंड से अप्रवास कर के दक्षिण में आ जाते थे और संभवतया तापमान गिरने पर फिर से उत्तर को लौट आते थे। फ्रेजर द्वीप की जनता में आश्चर्य के बावजूद, यह ज़ाहिर तौर पर कोई नया व्यवहार नहीं है और इससे पहले भी कई बार ऐसा पाया गया है कि वन्य मगरमच्छ गर्म नम मौसम के दौरान दक्षिण में जैसे ब्रिसबेन तक आ गए हों.

खारे पानी के मगरमच्छ आमतौर पर उष्णकटिबंधीय नम मौसम के दौरान दलदल और ताजे पानी की नदियों में पाए जाते हैं और शुष्क मौसम में नीचे की ओर ज्वारनदमुख की तरफ चले जाते हैं, कभी कभी बहुत दूर तक यात्रा करते हुए समुद्र के बाहर तक भी आ जाते हैं। मगरमच्छ को विशेष रूप से सबसे उपयुक्त ताजे पानी की नदियों में जगह पाने के लिए प्रभावी नर जीवों के साथ, खूब प्रतिस्पर्धा करनी पड़ती है। इस प्रकार से छोटे मगरमच्छ सीमांत नदी प्रणालियों और कभी कभी समुद्र में जाने कि लिए मजबूर हो जाते हैं। यह तथ्य इस जानवर के व्यापक वितरण को स्पष्ट करता है (यह भारत के पूर्वी तट से लेकर उत्तरी ऑस्ट्रेलिया तक पाया जाता है). साथ ही कभी कभी इसका अजीब स्थानों में पाया जाना भी इससे स्पष्ट हो जाता है (जैसे जापान के समुद्र में). खारे पानी के मगरमच्छ छोटे समूहों में तैरते हैं,15 से 18 मील प्रति घंटा (6.7 से 8.0 मी/से) लेकिन जब बड़े समूह में तैरने लगते हैं 2 से 3 मील/घंटा (0.9 से 1.3 मी/से)

खारे पानी का मगरमच्छ एक अवसरवादी शीर्ष शिकारी है जो इसके क्षेत्र में प्रवेश करने वाले लगभग किसी भी जानवर का शिकार कर सकता है, चाहे वह पानी में हो या शुष्क भूमि पर. वे इनके क्षेत्र में प्रवेश करने वाले मनुष्यों पर भी हमला करने के लिए जाने जाते हैं। किशोर जीवों को छोटे जानवरों का शिकार करने की मनाही होती है जैसे कीट, उभयचर, केंकड़े, छोटे सरीसृप और मछली.जैसे जैसे जानवर बड़ा होता जाता है, इसके आहार में कई प्रकार के जानवर शामिल होते जाते हैं, हालांकि अपेक्षाकृत छोटे आकार के शिकार भी एक व्यस्क के आहार का महत्वपूर्ण हिस्सा बनाते हैं। बड़े आकार के व्यस्क खारे पानी के मगरमच्छ अपनी रेंज में आने वाले किसी भी जानवर को खा सकते हैं, इसमें बन्दर, कंगारू, जंगली सूअर, डिंगो (एक प्रकार का कुत्ता), गोआना, पक्षी, घरेलू पशु, पालतू जानवर, मनुष्य, पानी की भैंस, गौर, चमगादड़ और यहां तक कि शार्क भी शामिल है।[10][19][20][21] घरेलू पशु, घोड़े, पानी की भैंस और गौर, वे सभी जिनका वजन एक टन से भी अधिक होता है, वे नर मगरमच्छ के द्वारा किये जाने वाले सबसे बड़े शिकार माने जाते हैं। आम तौर पर ये बहुत सुस्त होते हैं- यह एक ऐसी विशेषता है जिसकी वजह से ये कई महीनों तक भोजन के बिना जीवित रह सकते हैं- ये अक्सर पानी में मटरगश्ती करते हैं और दिन में धूप सेंकते हैं और रात में शिकार करना पसंद करते हैं। खारे पानी के मगरमच्छ जब पानी से हमला करते हैं तब विस्फोटक गति से आगे बढ़ते हैं।

मगरमच्छ की कहानियों को भूमि पर कम दूरी के लिए रेस के घोड़े की तुलना में अधिक जाना जाता है, ये शहरी कहानियों से कुछ बढ़कर हैं। पानी के किनारे पर, तथापि, वे दोनों पैरों और पूंछ से प्रणोदन गठजोड़ कर सकते हैं, इसका प्रत्यक्ष दर्शन दुर्लभ है।

हमला करने से पहले यह आमतौर पर इन्तजार करता है कि शिकार पानी के किनारे पर आ जाये, इसके बाद यह अपनी पूरी क्षमता से जानवर को पानी में खींच लेता है। ज्यादातर शिकार किये जाने वाले जानवरों को मगरमच्छ के जबड़े के दबाव से ही मार दिया जाता है, हालांकि कुछ जानवर संयोग से डूब जाते हैं। यह एक शक्तिशाली जानवर है, यह एक पूर्ण विकसित पानी की भैंस को नदी में घसीट सकता है, या पूर्ण विकसित बोविड को अपने जबड़ों से कुचल सकता है। इसकी शिकार की प्ररुपिओक तकनीक को "डेथ रोल" के रूप में जाना जाता है: यह जानवर को जकड का पूरी क्षमता के साथ रोल कर देता है। इससे किसी भी संघर्षरत जानवर का संतुलन बिगड़ जाता है, जिससे इसे पानी में खींचना आसान हो जाता है। "डेथ रोल" तकनीक का उपयोग एक मृत जानवर को फाड़ने के लिए भी किया जाता है।

खारे पानी के शिशु मगरमच्छ छिपकली, शिकारी मछली, पक्षी और कई अन्य शिकारियों का शिकार भी बन सकते हैं। किशोर अपनी रेंज के बंगाल टाइगर और तेंदुओं का भी शिकार बन सकते हैं, हालांकि यह दुर्लभ है।

एक शोधकर्ता, डॉ॰ एडम ब्रित्तन,[22] ने मगरमच्छों की होशियारी या सहजज्ञान पर अध्ययन किया है। उन्होंने ऑस्ट्रेलियाई मगरमच्छों के आवाजों के संग्रह को संकलित किया है,[23] और इन्हें उनके व्यवहार के साथ सम्बंधित किया है।

उनके अनुसार मगरमच्छ के मस्तिष्क का आकार स्तनधारियों की तुलना में काफी छोटा होता है (खारे पानी के मगरमच्छ में शरीर के भार का सिर्फ 0.05%), वे बहुत कम शर्तों के साथ बहुत मुश्किल काम को भी सीख सकते हैं। उन्होंने यह भी निष्कर्ष निकाला है कि मगरमच्छ की आवाज में भाषा की गहन क्षमता निहित है। जबकि वर्तमान में इस क्षमता को इतना अधिक स्वीकार नहीं किया गया है। उनका सुझाव है कि खारे पानी के मगरमच्छ चालाक जानवर हैं, जो प्रयोगशाला चूहों की तुलना में अधिक तेजी से सीख सकते हैं। वे मौसम में परिवर्तन के साथ अपने शिकार के अप्रवासी मार्ग का पता लगाना भी सीख लेते हैं।

ऑस्ट्रेलिया के बाहर हमलों के आंकड़े सीमित हैं। ऑस्ट्रेलिया में हमले दुर्लभ हैं और जब कभी ये हमले होते हैं, तो राष्ट्रीय समाचार प्रकाशनों में दिखाई देते हैं। देश में हर साल लगभग एक या दो घातक हमले दर्ज किये जाते हैं।[24] छोटे स्तर के हमले संभवतया ऑस्ट्रेलिया में वन्यजीव अधिकारीयों के द्वारा किये जाने वाले गहन प्रयासों के कारण होते हैं, जब वे कई जोखिम युक्त नदमुखों, नदियों, झीलों और समुद्र के किनारों पर चेतावनी के संकेत लगाने का काम कर रहे होते हैं। आर्न्हेम भूमि के बड़े आदिवासी समुदायों पर होने वाले हमले दर्ज ही नहीं किये जाते.[कृपया उद्धरण जोड़ें]

हाल ही में बोर्नियो,[25] सुमात्रा,[26] पूर्वी भारत (अंडमान द्वीप समूह)[27][28] और म्यांमार में हमले हुए हैं,[29] जिनका अधिक प्रचार नहीं हुआ।

19 फ़रवरी 1945 को रामरी द्वीप की लड़ाई में जब जापानी सैनिक लौट रहे थे, उस समय खारे पानी के मगरमच्छों ने उन पर हमला किया और इसमें 400 जापानी सैनिकों की मौत हो गयी। ब्रिटिश सैनिकों ने उस दलदल को घेर लिया, जहां से जापानी लौट रहे थे, एक रात के लिए जापानियों को उस मैंग्रोव में रुकना पड़ा, जहां हजारों की संख्या में खारे पानी के मगरमच्छ रहते थे।

रामरी के मगरमच्छ के इस हमले को गिनीज़ बुक ऑफ़ रिकॉर्ड्स में दर्ज किया गया है, इसका शीर्षक है "द ग्रेटेस्ट डिसास्टर सफर्ड फ्रॉम एनिमल्स".[30]

|isbn= के मान की जाँच करें: invalid character (मदद). Krokodile magarmach ias a best animal in attacing

खारे पानी का मगरमच्छ या एस्टूएराइन क्रोकोडाइल (estuarine crocodile) (क्रोकोडिलस पोरोसस) सबसे बड़े आकार का जीवित सरीसृप है। यह उत्तरी ऑस्ट्रेलिया, भारत के पूर्वी तट और दक्षिण-पूर्वी एशिया के उपयुक्त आवास स्थानों में पाया जाता है।

ਖਾਰੇ ਪਾਣੀ ਦਾ ਮਗਰਮੱਛ ਦੁਨੀਆਂ ਦਾ ਸਭ ਤੋਂ ਵੱਡਾ ਮਗਰਮੱਛ ਹੈ ਅਤੇ ਇਸ ਦੀ ਗਿਣਤੀ ਧਰਤੀ ’ਤੇ ਮੌਜੂਦ ਸਭ ਤੋਂ ਖਤਰਨਾਕ ਸ਼ਿਕਾਰੀਆਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਕੀਤੀ ਜਾਂਦੀ ਹੈ। ਇਹ ਮਗਰਮੱਛ ਬਿਹਤਰੀਨ ਤੈਰਾਕ ਹੁੰਦੇ ਹਨ ਅਤੇ ਸਮੁੰਦਰ ਦੇ ਬਹੁਤ ਦੂਰ-ਦਰਾਜ ਦੇ ਇਲਾਕਿਆਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਪਾਏ ਜਾਂਦੇ ਹਨ।[2] ਇਹ ਧਰਤੀ ਤੇ ਜ਼ਿੰਦਾ ਰਹਿਣ ਵਾਲਾ ਸਭ ਤੋਂ ਵੱਡਾ ਰੀਘਣਵਾਲਾ ਜੀਵ ਹੈ। ਨਰ ਮਗਰਮੱਛ ਦਾ ਲੰਬਾਈ 6.30 ਮੀ (20.7 ਫ਼ੁੱਟ) ਤੋਂ 7.0 ਮੀ (23.0 ਫ਼ੁੱਟ) ਤੱਕ ਹੋ ਸਕਦੀ ਹੈ। ਇਹਨਾਂ ਦਾ ਭਾਰ 1,000 to 1,200 kg (2,200–2,600 lb) ਤੱਕ ਹੋ ਜਾਂਦਾ ਹੈ। ਇਹ ਮਗਰਮੱਛ ਦੱਖਣੀ ਏਸ਼ੀਆ ਅਤੇ ਉੱਤਰੀ ਆਸਟਰੇਲੀਆ 'ਚ ਜ਼ਿਆਦਾ ਿਮਲਦੇ ਹਨ।

ਖਾਰੇ ਪਾਣੀ ਦਾ ਮਗਰਮੱਛ ਦੁਨੀਆਂ ਦਾ ਸਭ ਤੋਂ ਵੱਡਾ ਮਗਰਮੱਛ ਹੈ ਅਤੇ ਇਸ ਦੀ ਗਿਣਤੀ ਧਰਤੀ ’ਤੇ ਮੌਜੂਦ ਸਭ ਤੋਂ ਖਤਰਨਾਕ ਸ਼ਿਕਾਰੀਆਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਕੀਤੀ ਜਾਂਦੀ ਹੈ। ਇਹ ਮਗਰਮੱਛ ਬਿਹਤਰੀਨ ਤੈਰਾਕ ਹੁੰਦੇ ਹਨ ਅਤੇ ਸਮੁੰਦਰ ਦੇ ਬਹੁਤ ਦੂਰ-ਦਰਾਜ ਦੇ ਇਲਾਕਿਆਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਪਾਏ ਜਾਂਦੇ ਹਨ। ਇਹ ਧਰਤੀ ਤੇ ਜ਼ਿੰਦਾ ਰਹਿਣ ਵਾਲਾ ਸਭ ਤੋਂ ਵੱਡਾ ਰੀਘਣਵਾਲਾ ਜੀਵ ਹੈ। ਨਰ ਮਗਰਮੱਛ ਦਾ ਲੰਬਾਈ 6.30 ਮੀ (20.7 ਫ਼ੁੱਟ) ਤੋਂ 7.0 ਮੀ (23.0 ਫ਼ੁੱਟ) ਤੱਕ ਹੋ ਸਕਦੀ ਹੈ। ਇਹਨਾਂ ਦਾ ਭਾਰ 1,000 to 1,200 kg (2,200–2,600 lb) ਤੱਕ ਹੋ ਜਾਂਦਾ ਹੈ। ਇਹ ਮਗਰਮੱਛ ਦੱਖਣੀ ਏਸ਼ੀਆ ਅਤੇ ਉੱਤਰੀ ਆਸਟਰੇਲੀਆ 'ਚ ਜ਼ਿਆਦਾ ਿਮਲਦੇ ਹਨ।

ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀର ବା ଲୁଣା କୁମ୍ଭୀର (ଈଂରାଜୀରେ The Saltwater Crocodile, ଜୀବବିଜ୍ଞାନ ନାମ Crocodylus porosus) ଅନ୍ୟ ସମସ୍ତ ଜଳଚର ମାଂସଭୋଜୀ ଶିକାରୀ ଜୀବଙ୍କ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ଆକାରରେ ବୃହତ୍ତମ । ବର୍ତ୍ତମାନ ସମୟରେ ଦେଖାଯାଉଥିବା ସମସ୍ତ ସରୀସୃପଙ୍କ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ବି ଏହା ବଡ଼ । ବ୍ୟବହାରିକ ଈଂରାଜୀ ଭାଷାରେ ଏହାର ଅନେକ ଗୁଡ଼ିଏ ନାମ ରହିଛି, ଯଥା : estuarine crocodile (ମୁହାଣୁଆ କୁମ୍ଭୀର), Indo-Pacific crocodile (ଭାରତ-ପ୍ରଶାନ୍ତ ମହାସାଗରୀୟ କୁମ୍ଭୀର), marine crocodile (ସାମୁଦ୍ରିକ କୁମ୍ଭୀର), sea crocodile (ସମୁଦ୍ର କୁମ୍ଭୀର) ଅଥବା saltie (ଲୁଣା) ।[୨] ଏହି ପ୍ରଜାତିର ଅଣ୍ଡିରା କୁମ୍ଭୀରମାନେ ବଢ଼ି ପ୍ରାୟ ୭ ମିଟର୍ (୨୩ ଫୁଟ୍) ପର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ ଲମ୍ବା ହୋଇପାରନ୍ତି ।[୩] କିନ୍ତୁ ଏକ ବୟସ୍କ ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀର ୬ ମିଟର୍ (୧୯.୭ ଫୁଟ୍) ଟପିବା ଉଦାହରଣ କ୍ୱଚିତ୍ ଦେଖାଯାଏ ଓ ଏମାନଙ୍କ ଓଜନ ୧୦୦୦ରୁ ୧୨୦୦ କିଲୋଗ୍ରାମ୍ ପର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ ହୋଇପାରେ ।[୪] ମାଈ ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀରମାନେ ଆକାରରେ ଛୋଟ ଓ ପ୍ରାୟ ୩ ମିଟର୍ (୯.୮ ଫୁଟ୍) ପର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ ଲମ୍ବା ହୁଅନ୍ତି ।[୪]

ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀରମାନେ ସମୁଦ୍ରର ଲୁଣିଆ ପାଣିରେ ରହିପାରନ୍ତି । ତେବେ ଏହି ପ୍ରଜାତିର କୁମ୍ଭୀର ମୁଖ୍ୟତଃ ହେନ୍ତାଳ ବଣ ବା ଲୁଣା ଜଙ୍ଗଲର ନଦୀ ପାଣିରେ, ତ୍ରିକୋଣଭୂମି ଅଞ୍ଚଳରେ, ଲୁଣ ଓ ମଧୁର ପାଣି ମିଶା ହ୍ରଦରେ, ନଦୀ ମୁହାଣରେ ଦୃଶ୍ୟମାନ ହୁଅନ୍ତି । ବିଶ୍ୱର ସମସ୍ତ କୁମ୍ଭୀର ପ୍ରଜାତିମାନଙ୍କ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ଏହି ପ୍ରଜାତିର ଭୌଗୋଳିକ ବ୍ୟାପ୍ତି ସର୍ବାଧିକ । ଭାରତର ପୂର୍ବ ତଟରୁ ନେଇ, ଦକ୍ଷିଣ-ପୂର୍ବ ଏସିଆ, ଉତ୍ତର ଅଷ୍ଟ୍ରେଲିଆ ପର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀର ବସବାସ କରନ୍ତି । ପ୍ରାଚୀନ ସମୟରେ ଦକ୍ଷିଣ ଚୀନରେ ମଧ୍ୟ ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀର ବସବାସ କରୁଥିଲେ ।

ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀର ଏକ ବୃହତ୍ ଓ ସୁବିଧାବାଦୀ ଶିକାରୀ ଜୀବ । ନିଜ ପରିବାସରେ ଏହା ଖାଦ୍ୟ ଶୃଙ୍ଖଳର ଶୀର୍ଷରେ ରହିଥାଏ । ଛକି ରହି ଶିକାର ଉପରେ ଅତର୍କିତ ଭାବେ ଆକ୍ରମଣ କରି ଶିକାରକୁ ପାଣିରେ ବୁଡ଼ାଇ ମାରିଦେବା ପରେ ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀର ନିଜ ଶିକାରକୁ ଗୋଟା ଗିଳି ପକାଇଥାଏ । ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀର ନିଜ ଶିକାର କ୍ଷେତ୍ରର ପ୍ରାୟ ସମସ୍ତ ପ୍ରକାରର ଜୀବଙ୍କ ଶିକାର କରିପାରେ । ବଡ଼ ସାର୍କ୍ ମାଛ, ବିଭିନ୍ନ ଛୋଟ ବଡ଼ ମାଛ, ସରୀସୃପ, ପକ୍ଷୀ, ସ୍ତନ୍ୟପାୟୀ, ଅମେରୁଦଣ୍ଡୀ ସାମୁଦ୍ରିକ ଜୀବ ଏପରିକି ସମୟେ ସମୟେ ଏମାନେ ମଣିଷମାନଙ୍କୁ ମଧ୍ୟ ଆକ୍ରମଣ କରିବା ଦେଖାଯାଇଛି ।[୫][୬] ବଡ଼ ଆକାର, ଆକ୍ରମଣାତ୍ମକ ମନୋଭାବ ଓ ଭୌଗୋଳିକ ଦୃଷ୍ଟିରୁ ସର୍ବବ୍ୟାପ୍ତି ପାଇଁ ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀରମାନଙ୍କୁ ମନୁଷ୍ୟ ପାଇଁ ବିପଦ ବୋଲି ବିବେଚନା କରାଯାଏ । (ନୀଳ ନଦୀ କୁମ୍ଭୀରକୁ ମଧ୍ୟ ମନୁଷ୍ୟଙ୍କ ପାଇଁ ବିପଜ୍ଜନକ ବୋଲି କୁହାଯାଏ) ।[୭][୮]

ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀର ବା ଲୁଣା କୁମ୍ଭୀର (ଈଂରାଜୀରେ The Saltwater Crocodile, ଜୀବବିଜ୍ଞାନ ନାମ Crocodylus porosus) ଅନ୍ୟ ସମସ୍ତ ଜଳଚର ମାଂସଭୋଜୀ ଶିକାରୀ ଜୀବଙ୍କ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ଆକାରରେ ବୃହତ୍ତମ । ବର୍ତ୍ତମାନ ସମୟରେ ଦେଖାଯାଉଥିବା ସମସ୍ତ ସରୀସୃପଙ୍କ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ବି ଏହା ବଡ଼ । ବ୍ୟବହାରିକ ଈଂରାଜୀ ଭାଷାରେ ଏହାର ଅନେକ ଗୁଡ଼ିଏ ନାମ ରହିଛି, ଯଥା : estuarine crocodile (ମୁହାଣୁଆ କୁମ୍ଭୀର), Indo-Pacific crocodile (ଭାରତ-ପ୍ରଶାନ୍ତ ମହାସାଗରୀୟ କୁମ୍ଭୀର), marine crocodile (ସାମୁଦ୍ରିକ କୁମ୍ଭୀର), sea crocodile (ସମୁଦ୍ର କୁମ୍ଭୀର) ଅଥବା saltie (ଲୁଣା) । ଏହି ପ୍ରଜାତିର ଅଣ୍ଡିରା କୁମ୍ଭୀରମାନେ ବଢ଼ି ପ୍ରାୟ ୭ ମିଟର୍ (୨୩ ଫୁଟ୍) ପର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ ଲମ୍ବା ହୋଇପାରନ୍ତି । କିନ୍ତୁ ଏକ ବୟସ୍କ ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀର ୬ ମିଟର୍ (୧୯.୭ ଫୁଟ୍) ଟପିବା ଉଦାହରଣ କ୍ୱଚିତ୍ ଦେଖାଯାଏ ଓ ଏମାନଙ୍କ ଓଜନ ୧୦୦୦ରୁ ୧୨୦୦ କିଲୋଗ୍ରାମ୍ ପର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ ହୋଇପାରେ । ମାଈ ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀରମାନେ ଆକାରରେ ଛୋଟ ଓ ପ୍ରାୟ ୩ ମିଟର୍ (୯.୮ ଫୁଟ୍) ପର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ ଲମ୍ବା ହୁଅନ୍ତି ।

ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀରମାନେ ସମୁଦ୍ରର ଲୁଣିଆ ପାଣିରେ ରହିପାରନ୍ତି । ତେବେ ଏହି ପ୍ରଜାତିର କୁମ୍ଭୀର ମୁଖ୍ୟତଃ ହେନ୍ତାଳ ବଣ ବା ଲୁଣା ଜଙ୍ଗଲର ନଦୀ ପାଣିରେ, ତ୍ରିକୋଣଭୂମି ଅଞ୍ଚଳରେ, ଲୁଣ ଓ ମଧୁର ପାଣି ମିଶା ହ୍ରଦରେ, ନଦୀ ମୁହାଣରେ ଦୃଶ୍ୟମାନ ହୁଅନ୍ତି । ବିଶ୍ୱର ସମସ୍ତ କୁମ୍ଭୀର ପ୍ରଜାତିମାନଙ୍କ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ଏହି ପ୍ରଜାତିର ଭୌଗୋଳିକ ବ୍ୟାପ୍ତି ସର୍ବାଧିକ । ଭାରତର ପୂର୍ବ ତଟରୁ ନେଇ, ଦକ୍ଷିଣ-ପୂର୍ବ ଏସିଆ, ଉତ୍ତର ଅଷ୍ଟ୍ରେଲିଆ ପର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀର ବସବାସ କରନ୍ତି । ପ୍ରାଚୀନ ସମୟରେ ଦକ୍ଷିଣ ଚୀନରେ ମଧ୍ୟ ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀର ବସବାସ କରୁଥିଲେ ।

ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀର ଏକ ବୃହତ୍ ଓ ସୁବିଧାବାଦୀ ଶିକାରୀ ଜୀବ । ନିଜ ପରିବାସରେ ଏହା ଖାଦ୍ୟ ଶୃଙ୍ଖଳର ଶୀର୍ଷରେ ରହିଥାଏ । ଛକି ରହି ଶିକାର ଉପରେ ଅତର୍କିତ ଭାବେ ଆକ୍ରମଣ କରି ଶିକାରକୁ ପାଣିରେ ବୁଡ଼ାଇ ମାରିଦେବା ପରେ ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀର ନିଜ ଶିକାରକୁ ଗୋଟା ଗିଳି ପକାଇଥାଏ । ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀର ନିଜ ଶିକାର କ୍ଷେତ୍ରର ପ୍ରାୟ ସମସ୍ତ ପ୍ରକାରର ଜୀବଙ୍କ ଶିକାର କରିପାରେ । ବଡ଼ ସାର୍କ୍ ମାଛ, ବିଭିନ୍ନ ଛୋଟ ବଡ଼ ମାଛ, ସରୀସୃପ, ପକ୍ଷୀ, ସ୍ତନ୍ୟପାୟୀ, ଅମେରୁଦଣ୍ଡୀ ସାମୁଦ୍ରିକ ଜୀବ ଏପରିକି ସମୟେ ସମୟେ ଏମାନେ ମଣିଷମାନଙ୍କୁ ମଧ୍ୟ ଆକ୍ରମଣ କରିବା ଦେଖାଯାଇଛି । ବଡ଼ ଆକାର, ଆକ୍ରମଣାତ୍ମକ ମନୋଭାବ ଓ ଭୌଗୋଳିକ ଦୃଷ୍ଟିରୁ ସର୍ବବ୍ୟାପ୍ତି ପାଇଁ ବଉଳା କୁମ୍ଭୀରମାନଙ୍କୁ ମନୁଷ୍ୟ ପାଇଁ ବିପଦ ବୋଲି ବିବେଚନା କରାଯାଏ । (ନୀଳ ନଦୀ କୁମ୍ଭୀରକୁ ମଧ୍ୟ ମନୁଷ୍ୟଙ୍କ ପାଇଁ ବିପଜ୍ଜନକ ବୋଲି କୁହାଯାଏ) ।

செம்மூக்கு முதலை அல்லது செம்மூக்கன்[2] அல்லது உவர்நீர் முதலை (Crocodylus porosus) என்பது உயிர் வாழும் ஊர்வன இனங்கள் அனைத்திலும் மிகப் பெரியதாகும். இது வட அவுஸ்திரேலியா, இந்தியாவின் கிழக்குக் கரையோரம், இலங்கை, தென்கிழக்கு ஆசியாவின் பகுதிகள் என்பவற்றில் உள்ள பொருத்தமான வாழிடங்களில் பரவி வாழ்கிறது.

செம்மூக்கனின் முகப்பகுதி சாதாரண முதலையின் முகத்தைவிட நீண்டதாகும்: அதன் நீளம் அதன் தடிப்பிலும் இரு மடங்காகும்.[3] ஏனைய வகை முதலைகளை விடக் குறைவான அளவு செதில்களே உவர்நீர் முதலைகளின் கழுத்துப் பகுதியில் காணப்படுகிறது. இதன் காரணமாக, இவை முற்காலத்தில் அல்லிகேட்டர் வகை முதலையினமெனத் தவறாகக் கணிக்கப்பட்டது.[4]

வளர்ந்த ஒரு செம்மூக்கனின் நிறை 600-100 கிலோகிராம் ஆகவும் அதன் நீளம் 4.1-5.5 மீற்றர் ஆகவும் காணப்படும். எனினும், அவற்றின் நன்கு வளர்ச்சிடைந்த ஆண் முதலையொன்று 6 மீற்றர் நீளமும் 1300 கிலோகிராம் வரையான எடையும் கொண்டிருக்கலாம்.[5][6][7] இவ்வினம் தற்காலத்தில் வாழும் ஏனைய முதலை இனங்களிலும் பார்க்கக் கூடியளவான பாலியல் சார் நடத்தையைக் காட்டுகிறது. செம்மூக்கன்களின் பெண் உயிரினங்களின் உடலளவு 2.1-3.5 மீற்றர் ஆகும்.[4][5] இதுவரை பதிவு செய்யப்பட்ட மிகப் பெரிய பெண் செம்மூக்கனின் நீளம் 4.2 மீற்றர் ஆகும்.[7] பெண் செம்மூக்கனொன்றின் சாதாரண நிறை 450 கிலோகிராம் ஆகும்.[8]

இதுவரை அளவிடப்பட்ட மிகப் பெரிய செம்மூக்கனின் நீளம் அதன் முகத்திலிருந்து வால் நுனி வரை - அதன் தோலை அளந்ததன் படி - 6.1 மீற்றர் ஆகும். விலங்குகளின் தோல் அவற்றின் உடலிலிருந்து நீக்கப்பட்ட பின்னர் பொதுவாக சுருங்கும் தன்மையைக் கொண்டுள்ளமையால், மேற்படி முதலை உயிருடன் இருந்த போது 6.3 மீற்றர் நீளமும் 1200 கிலோகிராமுக்கு மேற்றபட்ட எடையும் கொண்டதாக இருந்துள்ளதென மதிப்பிடப்பட்டுள்ளது.[9] இந்தியாவின் ஒரிசா மாநிலத்தில்[10]) படம் பிடிக்கப்பட்ட ஒரு செம்மூக்கனின் மண்டையோடு, மேற்படி முதலை 7.6 மீட்டர் நீளமானதாக இருந்ததாகக் கூறப்பட்ட போதிலும் அது 7 மீட்டருக்கு மேற்பட்டிருக்காதென அறிஞர்கள் கூறுகின்றனர்.[9] செம்மூக்கன்கள் கிட்டத்தட்ட 9 மீற்றர் நீளமுள்ளனவாக இருந்ததாகவும் சிலர் கூறுகின்றனர்: 1840 ஆம் ஆண்டு வங்காள விரிகுடாவில் சுடப்பட்ட முதலையின் நீளம் 10 மீட்டராக இருந்தது; பிலிப்பீன்சு நாட்டில் 1823 ஆம் ஆண்டு கொல்லப்பட்ட முதலையின் நீளம் 8.2 மீட்டர் ஆகும்; கொல்கத்தா நகரின் ஹூக்லி ஆற்றில் கொல்லப்பட்ட முதலையின் நீளம் 7.6 மீட்டர் ஆகும். எனினும், மேற்படி முதலைகளின் மண்டையோடுகளைப் பரிசீலித்த பின்னர் அவை 6-6.6 மீட்டர் நீளமுள்ளனவாக இருந்ததிருக்கவே வாய்ப்புள்ளதாகக் கூறப்படுகிறது.

அண்மைக் காலத்தில் செம்மூக்கன்களுக்கான வாழிடங்களை வேறாக்கியுள்ளமையாலும் அவற்றை வேட்டையாடுதல் குறைவடைந்துள்ளமையாலும் தற்காலத்தில் 7 மீட்டர் நீளமான செம்மூக்கன்கள் உயிர் வாழக்கூடும்.[11] மிகச் சரியாக அளவிடப்படாவிடினும், கின்னஸ் உலக சாதனை அமைப்பு இந்தியாவின் ஒரிசா மாநிலத்திலுள்ள பிதார்கனிகா பூங்காவில் வாழும் ஏழு மீற்றர் முதலையைப் பதிவு செய்துள்ளது.[10][12].

1957 ஆம் ஆண்டு குயீன்ஸ்லாந்தில் சுடப்பட்ட முதலையொன்றின் நீளம் 8.5 மீட்டர் இருந்ததாகக் கூறப்பட்ட போதும் அதனைச் சரியாக அளவிட்டதாக உறுதிப்படுத்தப்படவில்லை என்பதுடன் அதன் எச்சங்களும் தற்போது காணப்படுவதில்லை. அங்கு அமைக்கப்பட்டுள்ள அம்முதலையின் உருவச்சிலை சுற்றுலாப் பயணிகளைக் கவரக்கூடியதாக உள்ளது.[13][14][15] 8 மீற்றரிலும் கூடிய முதலைகள் பற்றிப் பல்வேறு தகவல்கள் கூறினாலும் அவற்றிலெதுவும் உறுதிப்படுத்தப்படவில்லை.[16][17]

செம்மூக்கனானது சாதாரண முதலை, ஒடுங்கிய முதலை என்பவற்றுடன் சேர்த்து இந்தியாவில் காணப்படும் மூன்று முதலையினங்களில் ஒன்றாகும்.[18] இந்தியாவின் கிழக்குக் கரையோரப் பகுதிகளில் கணிசமாகக் காணப்பட்ட போதிலும் செம்மூக்கன்கள் இந்தியத் துணைக் கண்டத்தின் உட்பகுதிகளில் மிக அரிதாகவே காணப்படுகின்றன. இவை இந்தியாவின் ஒரிசா மாநிலத்தில் உள்ள பிதார்கனிகா வனவிலங்கு சரணாலயத்தில் பெருந்தொகையாகக் காணப்படும் அதே வேளை சுந்தரவனக் காடுகளின் இந்திய, வங்காள நாட்டுப் பகுதிகளிலும் ஏராளமாக வாழ்கின்றன.

அவுஸ்திரேலியாவின் வட பிராந்தியம், மேற்கு அவுஸ்திரேலியா, குயின்ஸ்லாந்து உள்ளிட்ட பகுதிகளின் மிக வடக்கான பகுதிகளில் செம்மூக்கன்கள் ஏராளமாகக் காணப்படுகின்றன. அங்கே 6 மீற்றரிலும் பெரிதான முதலைகள் சர்வசாதாரணமாகக் காணப்படுகின்றன. அவுஸ்திரேலிய செம்மூக்கன்களின் எண்ணிக்கை 100,000-200,000 இருக்கலாம் எனக் கணிக்கப்பட்டுள்ளது.

செம்மூக்கன்கள் தென்கிழக்காசியா முழுவதிலும் வாழ்ந்ததாக வரலாறு கூறிய போதிலும் அப்பகுதிகளில் இன்று அவை அருகிவிட்டன. செம்மூக்கன்கள் தாய்லாந்து, லாவோஸ், வியட்நாம், கம்போடியா ஆகிய நாடுகளில் முற்றாகவே அழிந்துவிட்டன. எனினும், இவை மியான்மர் நாட்டின் இராவாடி கழிமுகப் பகுதியில் ஏராளமாகக் காணப்படுகின்றன.[19] உவர்நீர் முதலைகளைக் கொண்டுள்ள இந்தோசீனப் பிராந்திய நாடு மியன்மார் மாத்திரமாக இருக்கலாம். இவை மேக்கொங் ஆற்றில் ஒரு காலத்தில் மிகப் பரவலாகக் காணப்பட்ட போதிலும் 1980களின் பின்னர் அவை பற்றிய தகவல்கள் கிடைக்கவில்லை. எனினும் அவை உலகளவில் முழுமையக அற்றுப் போவதற்கான வாய்ப்புக்கள் மிகக் குறைவாகவே காணப்படுகின்றன.

இந்தோனேசியா, மலேசியா ஆகிய நாடுகளின் போர்ணியோ தீவு போன்ற சில பகுதிகளில் இவை பெரும் எண்ணிக்கையிலும் பிலிப்பீன்சு போன்ற நாடுகளில் மிகக் குறைந்த எண்ணிக்கையிலும் காணப்படுகின்றன. சுமாத்திராவின் உட்பகுதிகளில் பெரிய அளவிலான முதலைகள் மனிதர்களைத் தாக்கியதாக அண்மையில் வெளிவந்த நம்பகமான தகவல்கள் இருப்பினும் சுமாத்திரா, சாவகம் போன்ற தீவுகளில் இவற்றின் எண்ணிக்கை பற்றிச் சரியாக அறியப்படவில்லை. முதலைகள் ஏராளமாகக் காணப்படும் வடக்கு அவுஸ்திரேலியாவுக்கு மிக அருகில் உள்ள போதிலும் பாலித் தீவில் உவர்நீர் முதலைகள் தற்போது காணப்படுவதில்லை. செம்மூக்கன்கள் தென்பசுபிக்குப் பிராந்தியத்தில் மிகக் குறைந்தளவில் காணப்படுகின்றன. ஆபிரிக்காவின் கிழக்குக் கரையோரம், சீசெல்சு ஆகிய இடங்களிலும் செம்மூக்கன்கள் ஒரு காலத்தில் பரவி வாழ்ந்தன.

செம்மூக்கு முதலை அல்லது செம்மூக்கன் அல்லது உவர்நீர் முதலை (Crocodylus porosus) என்பது உயிர் வாழும் ஊர்வன இனங்கள் அனைத்திலும் மிகப் பெரியதாகும். இது வட அவுஸ்திரேலியா, இந்தியாவின் கிழக்குக் கரையோரம், இலங்கை, தென்கிழக்கு ஆசியாவின் பகுதிகள் என்பவற்றில் உள்ள பொருத்தமான வாழிடங்களில் பரவி வாழ்கிறது.

ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಅಥವಾ ನದೀಮುಖದಲ್ಲಿರುವ ಮೊಸಳೆ ಯು (ಕ್ರಾಕಡೈಲಸ್ ಪೋರೋಸಸ್ ) ಎಲ್ಲಾ ಜೀವಂತ ಸರೀಸೃಪಗಳ ಪೈಕಿ ಅತಿದೊಡ್ಡದು ಎನಿಸಿಕೊಂಡಿದೆ. ಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾದ ಉತ್ತರಭಾಗ, ಭಾರತದ ಪೂರ್ವಭಾಗದ ಕರಾವಳಿ ಮತ್ತು ಆಗ್ನೇಯ ಏಷ್ಯಾದ ಭಾಗಗಳಲ್ಲಿನ ತನಗೆ ಸರಿಹೊಂದುವ ಆವಾಸಸ್ಥಾನಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಇದು ಕಂಡುಬರುತ್ತದೆ. ತಾನು ವಾಸಿಸುವಪ್ರದೇಶಗಳ ಸುತ್ತ ಮುತ್ತ ವಾಸಿಸುವ ಮನುಷ್ಯರ ಪಾಲಿಗೆ ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆ ಅತ್ಯಂತ ಅಪಾಯಕಾರಿ ಎನ್ನಲಾಗಿದೆ. ಮನುಷ್ಯರನ್ನು ಕೊಂದು ತಿಂದ ಹಲವು ಘಟನೆಗಳು ಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾದ ಕ್ವೀನ್ಸ್ಲೆಂಡ್, ನಾರ್ದರ್ನ್ ಟೆರಿಟರಿ ಹಾಗೂ ವೆಸ್ಟರ್ನಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾ ರಾಜ್ಯಗಳ ಉತ್ತರ ಕಡಲತೀರ ಪ್ರದೇಶಗಳಿಂದ ವರದಿಗಳು ಬಂದದ್ದುಂಟು.

ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಯು ಒಂದು ಉದ್ದನೆಯ ಮುಸುಡಿಯನ್ನು ಹೊಂದಿದ್ದು, ಅದು ಅಗಲ ಮುಸುಡಿಯ ಮೊಸಳೆಯದಕ್ಕಿಂತ ಉದ್ದವಾಗಿರುತ್ತದೆ: ಇದರ ಉದ್ದವು ತಳಭಾಗದಲ್ಲಿನ ಅದರ ಅಗಲಕ್ಕಿಂತ ದುಪ್ಪಟ್ಟು ಪ್ರಮಾಣದಲ್ಲಿರುತ್ತದೆ.[೧] ಮೊಸಳೆ ಜಾತಿಗೆ ಸೇರಿದ ಇತರ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳಿಗೆ ಹೋಲಿಸಿದಾಗ, ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಯು ಅಲ್ಪವೇ ಎನ್ನಬಹುದಾದ ರಕ್ಷಾಕವಚಗಳನ್ನು ತನ್ನ ಕುತ್ತಿಗೆಯ ಮೇಲೆ ಹೊಂದಿರುತ್ತದೆ. ಇದರ ಅಗಲವಾದ ಶರೀರವು ಬಹುಪಾಲು ಇತರ ತೆಳ್ಳಗಿನ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳ ಶರೀರಕ್ಕೆ ತದ್ವಿರುದ್ಧವಾಗಿದ್ದು, ಸದರಿ ಸರೀಸೃಪವು ಒಂದು ನೆಗಳು ಆಗಿತ್ತು ಎಂಬಂಥ, ದೃಢಪಡಿಸಲ್ಪಡದ ಆರಂಭಿಕ ಊಹೆಗಳಿಗೆ ಕಾರಣವಾಗುತ್ತದೆ.[೨]

ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ವಯಸ್ಕ ಗಂಡು ಮೊಸಳೆಯೊಂದರ ತೂಕವು 600 to 1,000 kilograms (1,300–2,200 lb)ನಷ್ಟಿರುತ್ತದೆ ಮತ್ತು ಉದ್ದವು ಸಾಮಾನ್ಯವಾಗಿ 4.1 to 5.5 metres (13–18 ft)ನಷ್ಟಿರುತ್ತದೆ; ಆದರೂ ಸಹ ಪ್ರೌಢ ಗಂಡು ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು 6 metres (20 ft)ನಷ್ಟು ಅಥವಾ ಅದಕ್ಕಿಂತ ಹೆಚ್ಚಿರಬಹುದು ಮತ್ತು 1,300 kilograms (2,900 lb)ನಷ್ಟು ಅಥವಾ ಅದಕ್ಕಿಂತ ಹೆಚ್ಚು ತೂಗಬಹುದು.[೩][೪][೫] ಆಧುನಿಕ ಯುಗದ ಮೊಸಳೆ ಜಾತಿಗೆ ಸೇರಿದ ಯಾವುದೇ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳ ಪೈಕಿ ಈ ಜಾತಿಯು ಮಹತ್ತರವಾದ ಲಿಂಗಾಧಾರಿತ ದ್ವಿರೂಪತೆಯನ್ನು ಹೊಂದಿದ್ದು, ಹೆಣ್ಣು ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಗಂಡು ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳಿಗಿಂತ ಸಾಕಷ್ಟು ಸಣ್ಣ ಗಾತ್ರದಲ್ಲಿರುತ್ತವೆ. ವಿಶಿಷ್ಟವಾದ ಹೆಣ್ಣು ಮೊಸಳೆಯ ಶರೀರದ ಉದ್ದವು 2.1 to 3.5 metres (7–11 ft)ರ ಶ್ರೇಣಿಯಲ್ಲಿ ಬರುತ್ತದೆ.[೨][೩][೬] ದಾಖಲೆಯಲ್ಲಿ ನಮೂದಾಗಿರುವ ಅತಿದೊಡ್ಡ ಹೆಣ್ಣು ಮೊಸಳೆಯು ಸುಮಾರು 4.2 metres (14 ft)ನಷ್ಟು ಅಳತೆಯನ್ನು ಹೊಂದಿತ್ತು.[೫] ಸಮಗ್ರವಾಗಿ ಹೇಳುವುದಾದರೆ, ಇದರ ಜಾತಿಯ ಸರಾಸರಿ ತೂಕವು ಸರಿಸುಮಾರಾಗಿ 450 kilograms (1,000 lb)ನಷ್ಟಿರುತ್ತದೆ.[೭]

ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ತಲುಪಬಲ್ಲ ಅತಿದೊಡ್ಡ ಗಾತ್ರವು, ಪರಿಗಣನಾರ್ಹ ವಿವಾದದ ವಿಷಯವಾಗಿದೆ. ಮುಸುಡಿಯಿಂದ-ಬಾಲದವರೆಗೆ ಅಳೆಯಲ್ಪಟ್ಟ ಮತ್ತು ಪರಿಶೀಲಿಸಲ್ಪಟ್ಟ ಇದುವರೆಗಿನ ಅತಿಉದ್ದದ ಮೊಸಳೆಯು, ಸತ್ತ ಮೊಸಳೆಯೊಂದರ ಚರ್ಮವಾಗಿದ್ದು ಇದು 6.1 metres (20 ft)ನಷ್ಟು ಉದ್ದವಿತ್ತು. ಮೃತದೇಹದಿಂದ ತೆಗೆದ ನಂತರ ಚರ್ಮಗಳು ಕೊಂಚಮಟ್ಟಿಗೆ ಮುದುರಿಕೊಳ್ಳುವ ಪ್ರವೃತ್ತಿಯನ್ನು ಹೊಂದಿರುತ್ತವೆಯಾದ್ದರಿಂದ, ಈ ಮೊಸಳೆಯು ಜೀವಂತವಿದ್ದಾಗಿನ ಉದ್ದವು 6.3 metres (21 ft)ನಷ್ಟಿತ್ತು ಎಂದು ಅಂದಾಜಿಸಲಾಯಿತು, ಮತ್ತು ಇದು ಪ್ರಾಯಶಃ 1,200 kilograms (2,600 lb)ಕ್ಕೂ ಹೆಚ್ಚು ತೂಗುತ್ತಿತ್ತು.[೮] ಅಪೂರ್ಣ ಅವಶೇಷಗಳು (ಒಡಿಶಾದಲ್ಲಿ[೯] ಗುಂಡಿಕ್ಕಿ ಸಾಯಿಸಲಾದ ಮೊಸಳೆಯೊಂದರ ತಲೆಬುರುಡೆ) 7.6-metre (25 ft)ನಷ್ಟಿರುವ ಮೊಸಳೆಯೊಂದರಿಂದ ಬಂದವಾಗಿವೆ ಎಂದು ಸಮರ್ಥಿಸಲ್ಪಟ್ಟಿದೆಯಾದರೂ, ಅದು 7 metres (23 ft)ಕ್ಕಿಂತ ಅಷ್ಟೇನೂ ಹೆಚ್ಚಿರದ ಒಂದು ಉದ್ದವನ್ನು ಹೊಂದಿತ್ತು ಎಂಬುದಾಗಿ ವಿದ್ವತ್ಪೂರ್ಣ ಅವಲೋಕನವು ಸೂಚಿಸಿತು.[೮] 9-metre (30 ft)ರ ಶ್ರೇಣಿಯಲ್ಲಿನ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳ ಕುರಿತಾಗಿ ಹಲವಾರು ಸಮರ್ಥನೆಗಳು ಮಂಡಿಸಲ್ಪಟ್ಟಿವೆ: 1840ರಲ್ಲಿ ಬಂಗಾಳ ಕೊಲ್ಲಿಯಲ್ಲಿ ಸಾಯಿಸಲ್ಪಟ್ಟ ಮೊಸಳೆಯು 10 metres (33 ft)ನಷ್ಟಿತ್ತೆಂದು ವರದಿಮಾಡಲ್ಪಟ್ಟಿತು; ಫಿಲಿಪೈನ್ಸ್ನಲ್ಲಿನ ಲುಜಾನ್ ಮುಖ್ಯದ್ವೀಪದಲ್ಲಿರುವ ಜಲಜಾಲ ಎಂಬಲ್ಲಿ 1823ರಲ್ಲಿ ಸಾಯಿಸಲ್ಪಟ್ಟ ಮತ್ತೊಂದು ಮೊಸಳೆಯು 8.2 metres (27 ft)ನಷ್ಟಿತ್ತೆಂದು ವರದಿಮಾಡಲ್ಪಟ್ಟಿತು; 7.6 metres (25 ft)ನಷ್ಟಿತ್ತೆಂದು ವರದಿಮಾಡಲ್ಪಟ್ಟ ಮೊಸಳೆಯೊಂದು ಕಲ್ಕತ್ತಾದ ಆಲಿಪೋರ್ ಜಿಲ್ಲೆಯಲ್ಲಿನ ಹೂಗ್ಲಿ ನದಿಯಲ್ಲಿ ಸಾಯಿಸಲ್ಪಟ್ಟಿತು. ಆದಾಗ್ಯೂ, ಈ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳ ತಲೆಬುರುಡೆಗಳನ್ನು ಅವಲೋಕಿಸಿದಾಗ, ಅವು 6 to 6.6 metres (20–22 ft)ನಷ್ಟು ವ್ಯಾಪ್ತಿಯನ್ನು ಹೊಂದಿದ್ದ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳಿಗೆ ಸೇರಿದ್ದವು ಎಂದು ಸದರಿ ಅವಲೋಕನಗಳು ಸೂಚಿಸಿದವು.

ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಯ ಆವಾಸಸ್ಥಾನವನ್ನು ಇತ್ತೀಚಿಗೆ ಪುನಃಸ್ಥಾಪನೆ ಮಾಡಿದ್ದರಿಂದಾಗಿ ಹಾಗೂ ಕಳ್ಳಬೇಟೆಯಾಡುವಿಕೆಯು ತಗ್ಗಿದ ಕಾರಣದಿಂದಾಗಿ, 7-metre (23 ft)ನಷ್ಟಿರುವ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಇಂದು ಜೀವಂತವಾಗಿರುವ ಸಾಧ್ಯತೆಯಿದೆ.[೧೦] ಭಾರತದ[೯][೧೧] ಒಡಿಶಾ ರಾಜ್ಯದಲ್ಲಿನ ಭಿತರ್ಕನಿಕಾ ಉದ್ಯಾನದ ವ್ಯಾಪ್ತಿಯೊಳಗೆ, 7-metre (23 ft)ನಷ್ಟಿರುವ ಒಂದು ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಗಂಡು ಮೊಸಳೆಯು ಜೀವಂತವಾಗಿರುವುದರ ಕುರಿತಾದ ಸಮರ್ಥನೆಯೊಂದನ್ನು ಗಿನ್ನೆಸ್ ಅಂಗೀಕರಿಸಿದೆಯಾದರೂ, ಅತ್ಯಂತ ದೊಡ್ಡದಾದ ಜೀವಂತ ಮೊಸಳೆಯೊಂದನ್ನು ಬಲೆಗೆ ಕೆಡವುವಿಕೆ ಮತ್ತು ಅಳೆಯುವಿಕೆಯ ಹಿಂದಿರುವ ಕ್ಲಿಷ್ಟತೆಯ ಕಾರಣದಿಂದಾಗಿ ಈ ಅಳತೆಗಳ ನಿಖರತೆಯನ್ನು ಇನ್ನೂ ಪರಿಶೀಲಿಸಬೇಕಾಗಿದೆ.

1957ರಲ್ಲಿ ಕ್ವೀನ್ಸ್ಲೆಂಡ್ನಲ್ಲಿ ಹೊಡೆದುರುಳಿಸಲಾದ ಮೊಸಳೆಯೊಂದು 8.5 metres (28 ft)ನಷ್ಟು ಉದ್ದವಿತ್ತೆಂದು ವರದಿಮಾಡಲ್ಪಟ್ಟಿತಾದರೂ, ಯಾವುದೇ ಪ್ರಮಾಣೀಕರಿಸಲ್ಪಟ್ಟ ಅಳತೆಗಳು ಲಭ್ಯವಾಗಲಿಲ್ಲ ಮತ್ತು ಈ ಮೊಸಳೆಯ ಅವಶೇಷಗಳು ಅಸ್ತಿತ್ವದಲ್ಲಿಲ್ಲ. ಈ ಮೊಸಳೆಯ "ಪ್ರತಿರೂಪ"ವೊಂದನ್ನು ಒಂದು ಪ್ರವಾಸಿ ಆಕರ್ಷಣೆಯನ್ನಾಗಿಸಲಾಗಿದೆ.[೧೨][೧೩][೧೪] 8+ ಮೀಟರುಗಳಷ್ಟು (28+ ಅಡಿ) ಉದ್ದದ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳ ಕುರಿತಾದ ಇತರ ಅನೇಕ ದೃಢಪಟ್ಟಿಲ್ಲದ ವರದಿಗಳು ಲಭ್ಯವಿವೆಯಾದರೂ,[೧೫][೧೬] ಇವು ತೀರಾ ಅಸಂಭವ ಎಂದು ಹೇಳಬಹುದು.

ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಯು ಭಾರತದಲ್ಲಿ ಕಂಡುಬರುವ ಮೂರು ಮೊಸಳೆ ಜಾತಿಗೆ ಸೇರಿದ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳ ಪೈಕಿ ಒಂದೆನಿಸಿದ್ದು, ಅಗಲ ಮುಸುಡಿಯ ಮೊಸಳೆ ಮತ್ತು ಏಷ್ಯಾದ ಉದ್ದಮೂತಿಯ ಮೊಸಳೆ ಉಳಿದೆರಡು ಬಗೆಗಳಾಗಿವೆ.[೧೭] ಭಾರತದ ಪೂರ್ವಭಾಗದ ಕರಾವಳಿಯನ್ನು ಹೊರತುಪಡಿಸಿ, ಈ ಮೊಸಳೆಯು ಭಾರತೀಯ ಉಪಖಂಡದಲ್ಲಿ ಅತ್ಯಂತ ಅಪರೂಪವಾಗಿದೆ. ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳ (7 ಮೀಟರು ಉದ್ದದ ಒಂದು ಗಂಡು ಮೊಸಳೆಯೂ ಸೇರಿದಂತೆ ಅನೇಕ ದೊಡ್ಡ ವಯಸ್ಕ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳನ್ನು ಒಳಗೊಂಡಿರುವ) ಒಂದು ಬೃಹತ್ ಸಂಖ್ಯೆಯು ಒಡಿಶಾದ ಭಿತರ್ಕನಿಕಾ ವನ್ಯಜೀವಿಕುಲ ಅಭಯಾರಣ್ಯದ ವ್ಯಾಪ್ತಿಯೊಳಗೆ ಅಸ್ತಿತ್ವದಲ್ಲಿದೆ ಮತ್ತು ಅವು ಸುಂದರಬನಗಳ ಭಾರತೀಯ ಭಾಗ ಮತ್ತು ಬಾಂಗ್ಲಾದೇಶ ಭಾಗಗಳಾದ್ಯಂತವೂ ಸಣ್ಣ ಸಂಖ್ಯೆಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಇವೆ ಎಂದು ಹೇಳಲಾಗುತ್ತದೆ.

ಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾದ ಉತ್ತರಭಾಗದಲ್ಲಿ (ಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾದ ಪಶ್ಚಿಮಭಾಗ, ಕ್ವೀನ್ಸ್ಲೆಂಡ್ ಮತ್ತು ಉತ್ತರಭಾಗದ ಪ್ರದೇಶದ (ನಾರ್ದರ್ನ್ ಟೆರಿಟರಿ (Northern Territory)) ಅತ್ಯಂತ ಉತ್ತರದಲ್ಲಿರುವ ಭಾಗಗಳನ್ನು ಇದು ಒಳಗೊಂಡಿದೆ) ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಯು ಹಸನಾಗಿ ವರ್ಧಿಸುತ್ತಿದೆ; ಅದರಲ್ಲೂ ನಿರ್ದಿಷ್ಟವಾಗಿ, ಡಾರ್ವಿನ್ ಸಮೀಪದಲ್ಲಿರುವ ಬಹುವಿಧದ ನದಿ ವ್ಯವಸ್ಥೆಗಳಲ್ಲಿ (ಅಡಿಲೇಡ್, ಮೇರಿ ಮತ್ತು ಡಾಲಿ ನದಿಗಳು, ಅವುಗಳ ಪಕ್ಕದ ತುಂಡುತೊರೆಗಳು ಮತ್ತು ನದೀಮುಖಗಳು ಇವೇ ಮೊದಲಾದವು) ಈ ವಿಶಿಷ್ಟತೆಯು ಕಂಡುಬಂದಿದ್ದು, ಇಲ್ಲಿ ದೊಡ್ಡ ಗಾತ್ರದ (6 ಮೀಟರು +) ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಸಾಮಾನ್ಯವಾಗಿವೆ. ಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾದ ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳ ಒಟ್ಟುಸಂಖ್ಯೆಯು 100,000 ಮತ್ತು 200,000ದಷ್ಟು ವಯಸ್ಕ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳಷ್ಟರ ನಡುವೆ ಇರಬಹುದು ಎಂದು ಅಂದಾಜಿಸಲಾಗಿದೆ. ಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾದ ಪಶ್ಚಿಮಭಾಗದಲ್ಲಿನ ಬ್ರೂಮೆಯಿಂದ ಮೊದಲ್ಗೊಂಡು ಉತ್ತರಭಾಗದ ಪ್ರದೇಶದ ಸಮಗ್ರ ಕರಾವಳಿಯ ಮೂಲಕ ಹಾದು, ಕ್ವೀನ್ಸ್ಲೆಂಡ್ನಲ್ಲಿನ ರಾಕ್ಹ್ಯಾಂಪ್ಟನ್ವರೆಗೆ ಅವುಗಳ ಶ್ರೇಣಿಯು ವ್ಯಾಪಿಸುತ್ತದೆ. ಉತ್ತರಭಾಗದ ಪ್ರದೇಶದಲ್ಲಿಯೂ ವಾಸಿಸುವ ಸಿಹಿನೀರಿನ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳಿಗೆ ಹೋಲಿಸಲ್ಪಟ್ಟಂತೆ, ನೆಗಳುಗಳಿಗೆ ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಯ ಹೋಲಿಕೆಯಿರುವುದರ ಕಾರಣದಿಂದಾಗಿ, ಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾದ ಉತ್ತರಭಾಗದ ನೆಗಳು ನದಿಗಳು ಆ ರೀತಿಯಲ್ಲಿ ತಪ್ಪಾಗಿ ಹೆಸರಿಸಲ್ಪಟ್ಟಿವೆ. ನ್ಯೂಗಿನಿಯಾದಲ್ಲಿ ಅವೂ ಸಹ ಸಾಮಾನ್ಯವಾಗಿದ್ದು, ವಸ್ತುತಃ ದೇಶದಲ್ಲಿನ ಪ್ರತಿಯೊಂದು ನದಿ ವ್ಯವಸ್ಥೆಯ ಕರಾವಳಿಯ ಅವಿಚ್ಛಿನ್ನ ಹರವುಗಳೊಳಗೆ, ಎಲ್ಲಾ ನದೀಮುಖಗಳು ಮತ್ತು ಮ್ಯಾಂಗ್ರೋವ್ಗಳ ಉದ್ದಕ್ಕೂ ಅವು ಕಂಡುಬರುತ್ತವೆ. ಬಿಸ್ಮಾರ್ಕ್ ದ್ವೀಪಸಮೂಹ, ಕಾಯ್ ದ್ವೀಪಗಳು, ಅರು ದ್ವೀಪಗಳು, ಮಲುಕು ದ್ವೀಪಗಳು ಹಾಗೂ ಟಿಮೋರ್ ಸೇರಿದಂತೆ ಪ್ರದೇಶದ ವ್ಯಾಪ್ತಿಯೊಳಗಿನ ಇತರ ಅನೇಕ ದ್ವೀಪಗಳು, ಮತ್ತು ಟೋರೆಸ್ ಜಲಸಂಧಿಯ ವ್ಯಾಪ್ತಿಯೊಳಗಿನ ಬಹುತೇಕ ದ್ವೀಪಗಳಾದ್ಯಂತವೂ, ಬದಲಾಗುತ್ತಿರುವ ಸಂಖ್ಯೆಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಅವು ಕಾಣಿಸಿಕೊಳ್ಳುತ್ತವೆ.

ಐತಿಹಾಸಿಕವಾಗಿ ಹೇಳುವುದಾದರೆ, ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಯು ಆಗ್ನೇಯ ಏಷ್ಯಾದ ಉದ್ದಗಲಕ್ಕೂ ಕಂಡುಬಂದಿತ್ತಾದರೂ, ಅದರ ಬಹುಪಾಲು ಶ್ರೇಣಿಯು ಈಗ ನಿರ್ನಾಮವಾಗಿದೆ. ಇಂಡೋಚೈನಾದ ಬಹುತೇಕ ಭಾಗಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಈ ಜಾತಿಯು ಕಾಡುಸ್ಥಿತಿಯಲ್ಲಿರುವುದು ದಶಕಗಳಿಂದಲೂ ವರದಿಮಾಡಲ್ಪಟ್ಟಿಲ್ಲ ಮತ್ತು ಥೈಲೆಂಡ್, ಲಾವೋಸ್, ವಿಯೆಟ್ನಾಂಗಳಲ್ಲಿ, ಹಾಗೂ ಪ್ರಾಯಶಃ ಕಾಂಬೋಡಿಯಾದಲ್ಲಿಯೂ ಇದು ನಿರ್ನಾಮವಾಗಿದೆ. ಮ್ಯಾನ್ಮಾರ್ನ ಬಹುತೇಕ ಭಾಗಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಈ ಜಾತಿಯ ಸ್ಥಿತಿಗತಿಯು ವಿಷಮಸ್ಥಿತಿಯನ್ನು ತಲುಪಿದೆಯಾದರೂ, ಇರಾವ್ಯಾಡಿ ನದೀ ಮುಖಜ ಭೂಮಿಯಲ್ಲಿ ಅಸ್ತಿತ್ವದಲ್ಲಿರುವ ಅನೇಕ ದೊಡ್ಡ ವಯಸ್ಕ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳಿಂದಾಗಿ ಅಲ್ಲೊಂದು ಸ್ಥಿರವಾದ ಸಮೂಹವಿದೆ ಎಂದು ತಿಳಿದುಬರುತ್ತದೆ.[೧೮] ಮ್ಯಾನ್ಮಾರ್ ದೇಶವು ಈ ಜಾತಿಯ ಕಾಡುಪ್ರಭೇದದ ಸಮೂಹಕ್ಕೆ ಈಗಲೂ ಆಶ್ರಯ ಕೊಟ್ಟಿರುವ ಇಂಡೋಚೈನಾ ವಲಯದ ಏಕೈಕ ದೇಶವಾಗಿರುವ ಸಂಭವವಿದೆ. ಮೆಕಾಂಗ್ ನದೀ ಮುಖಜ ಭೂಮಿಯಲ್ಲಿ (1980ರ ದಶಕದಲ್ಲಿ ಈ ಪ್ರದೇಶದಿಂದ ಅವು ಕಣ್ಮರೆಯಾದವು) ಮತ್ತು ಇತರ ನದಿ ವ್ಯವಸ್ಥೆಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಹಿಂದೊಮ್ಮೆ ಅತ್ಯಂತ ಸಾಮಾನ್ಯವಾಗಿದ್ದವಾದರೂ, ಇಂಡೋಚೈನಾದಲ್ಲಿನ ಈ ಜಾತಿಯ ಭವಿಷ್ಯವು ಈಗ ಕರಾಳವಾಗಿ ಕಾಣಿಸುತ್ತಿದೆ. ಆದಾಗ್ಯೂ, ಮೊಸಳೆ ಜಾತಿಗೆ ಸೇರಿದ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳ ವ್ಯಾಪಕ ಹರಡಿಕೆಯ ಕಾರಣದಿಂದಾಗಿ ಮತ್ತು ಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾದ ಉತ್ತರಭಾಗ ಹಾಗೂ ನ್ಯೂಗಿನಿಯಾಗಳಲ್ಲಿನ ಹೆಚ್ಚೂಕಮ್ಮಿ ವಸಾಹತಿನ-ಪೂರ್ವದ ಸಂಖ್ಯಾಗಾತ್ರಗಳ ಕಾರಣದಿಂದಾಗಿ, ಈ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳು ಜಾಗತಿಕವಾಗಿ ನಿರ್ನಾಮವಾಗುವ ಸ್ಥಿತಿಯನ್ನು ತಲುಪುವ ಸಾಧ್ಯತೆ ಕಡಿಮೆ ಎನ್ನಬಹುದು.

ಇಂಡೋನೇಷಿಯಾ ಮತ್ತು ಮಲೇಷಿಯಾಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಇವುಗಳ ಒಟ್ಟುಸಂಖ್ಯೆಯು ವಿರಳವಾಗಿದ್ದರೆ, ಕೆಲವೊಂದು ಪ್ರದೇಶಗಳು (ಉದಾಹರಣೆಗೆ, ಬೋರ್ನಿಯೊ) ದೊಡ್ಡದಾದ ಸಮೂಹಕ್ಕೆ ಆಶ್ರಯ ಕೊಟ್ಟಿವೆ ಹಾಗೂ ಇತರ ಪ್ರದೇಶಗಳು ತೀರಾ ಸಣ್ಣದೆನ್ನಬಹುದಾದ, ಅಪಾಯದಲ್ಲಿರುವ ಸಮೂಹಕ್ಕೆ ಆಶ್ರಯನೀಡಿವೆ (ಉದಾಹರಣೆಗೆ, ಫಿಲಿಪೈನ್ಸ್). ಸುಮಾತ್ರಾ ಮತ್ತು ಜಾವಾ ವಲಯಗಳ ವ್ಯಾಪ್ತಿಯೊಳಗೆ ಈ ಜಾತಿಯ ಸ್ಥಿತಿಗತಿಯೇನಾಗಿದೆ ಎಂಬುದು ಬಹುಮಟ್ಟಿಗೆ ತಿಳಿದುಬಂದಿಲ್ಲ (ಆದರೂ, ಸುಮಾತ್ರಾದ ಪ್ರತ್ಯೇಕಿಸಲ್ಪಟ್ಟ ಪ್ರದೇಶಗಳ ವ್ಯಾಪ್ತಿಯೊಳಗೆ ದೊಡ್ಡ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಮಾನವರ ಮೇಲೆ ದಾಳಿಗಳನ್ನು ಮಾಡಿರುವುದರ ಕುರಿತಾಗಿ ಸುದ್ದಿ ಸಂಸ್ಥೆಗಳು ಇತ್ತೀಚೆಗೆ ವರದಿಗಳನ್ನು ನೀಡಿದ್ದು, ಅವು ವಿಶ್ವಾಸಾರ್ಹವೆಂದು ಭಾವಿಸಲ್ಪಟ್ಟಿವೆ). ಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾದ ಉತ್ತರಭಾಗದ ಮೊಸಳೆಯ ಆವಾಸಸ್ಥಾನಕ್ಕೆ ಅತಿ ಸಾಮೀಪ್ಯವನ್ನು ಹೊಂದಿದ್ದರೂ ಸಹ, ಬಾಲಿಯಲ್ಲಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಕಂಡುಬರುತ್ತಿಲ್ಲ. ದಕ್ಷಿಣ ಪೆಸಿಫಿಕ್ನ ಅತ್ಯಂತ ಸೀಮಿತ ಭಾಗಗಳಲ್ಲಿಯೂ ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಕಂಡುಬರುತ್ತವೆ; ಸಾಲೊಮನ್ ದ್ವೀಪಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಇವು ಒಂದು ಸಾಧಾರಣವೆನ್ನಬಹುದಾದ ಒಟ್ಟುಸಂಖ್ಯೆಯಿದ್ದರೆ, ವನುವಾಟುವಿನಲ್ಲಿ ಒಂದು ಅತ್ಯಂತ ಸಣ್ಣ, ಆಕ್ರಮಣಶೀಲ ಮತ್ತು ಕೆಲವೇ ದಿನಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ನಿರ್ನಾಮವಾಗಲಿರುವ ಸಮೂಹವಿದೆ (ಇಲ್ಲಿ ಒಟ್ಟುಸಂಖ್ಯೆಯು ಅಧಿಕೃತವಾಗಿ ಕೇವಲ ಮೂರಕ್ಕೆ ನಿಲ್ಲುತ್ತದೆ) ಮತ್ತು ಪಲಾವು ಎಂಬಲ್ಲಿ ಒಂದು ತಕ್ಕಮಟ್ಟಿನ ಆದರೆ ಅಪಾಯದಲ್ಲಿರುವ ಒಟ್ಟುಸಂಖ್ಯೆಯನ್ನು (ಇದು ಮರಳುತ್ತಿರಬಹುದು) ಕಾಣಬಹುದು. ಆಫ್ರಿಕಾದ ಪೂರ್ವ ಕರಾವಳಿಯಿಂದ ಸೆಷೆಲ್ಸ್ ದ್ವೀಪಗಳಲ್ಲಿನ ಪಶ್ಚಿಮ ಕರಾವಳಿಯಷ್ಟು ದೂರದವರೆಗೆ ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಹಿಂದೊಮ್ಮೆ ವ್ಯಾಪಿಸಿದ್ದವು. ಈ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ನೈಲ್ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳ ಒಂದು ಸಮೂಹವೆಂದು ಒಮ್ಮೆ ನಂಬಲಾಗಿತ್ತು, ಆದರೆ ಅವು ಕ್ರಾಕಡೈಲಸ್ ಪೋರೋಸಸ್ ಎಂಬುದಾಗಿ ನಂತರದಲ್ಲಿ ಸಾಬೀತಾಯಿತು.[೨]

ಸಮುದ್ರದಲ್ಲಿ ಅತ್ಯಂತ ಸುದೀರ್ಘ ಅಂತರಗಳವರೆಗೆ ಸಂಚರಿಸುವ ಈ ಜಾತಿಯ ಪ್ರವೃತ್ತಿಯಿಂದಾಗಿ, ಪ್ರತ್ಯೇಕ ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ತಾವು ಸ್ಥಳೀಕವಾಗಿಲ್ಲದ ಊಹಿಸಲಾಗದ ಘಟನಾ ಪ್ರದೇಶಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಸಾಂದರ್ಭಿಕವಾಗಿ ಕಾಣಿಸಿಕೊಳ್ಳುತ್ತವೆ. ಅಲೆದಾಡುವ ಪ್ರತ್ಯೇಕ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ನ್ಯೂ ಕ್ಯಾಲೆಡೋನಿಯಾ, ಇವೋ ಜಿಮಾ, ಫಿಜಿಯಲ್ಲಿ ಮತ್ತು ತುಲನಾತ್ಮಕವಾಗಿ ಕಡುಚಳಿಯನ್ನು ಹೊಂದಿರುವ ಜಪಾನ್ನ ಸಮುದ್ರದಲ್ಲಿಯೂ (ತಮ್ಮ ಸ್ಥಳೀಕ ಪ್ರದೇಶದಿಂದ ಸಾವಿರಾರು ಮೈಲುಗಳಷ್ಟು ದೂರದಲ್ಲಿ) ಐತಿಹಾಸಿಕವಾಗಿ ವರದಿಮಾಡಲ್ಪಟ್ಟಿವೆ. 2008ರ ಅಂತ್ಯಭಾಗ/2009ರ ಆರಂಭಿಕ ಭಾಗದಲ್ಲಿ, ಫ್ರೇಸರ್ ದ್ವೀಪದ ನದಿ ವ್ಯವಸ್ಥೆಗಳ ವ್ಯಾಪ್ತಿಯಲ್ಲಿ ಒಂದು ಕೈಬೆರಳೆಣಿಕೆಯಷ್ಟು ಕಾಡುಸ್ಥಿತಿಯ ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ವಾಸಿಸುತ್ತಿರುವುದಾಗಿ ಪ್ರಮಾಣೀಕರಿಸಲ್ಪಟ್ಟವು; ಈ ಪ್ರದೇಶವು ಆ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳ ಸಾಮಾನ್ಯ ಕ್ವೀನ್ಸ್ಲೆಂಡ್ ವ್ಯಾಪ್ತಿಯಿಂದ ನೂರಾರು ಕಿಲೋಮೀಟರುಗಳಷ್ಟು ದೂರವಿರುವ ಪ್ರದೇಶವಾಗಿದ್ದು, ಇಲ್ಲಿನ ನೀರು ಬಹಳಷ್ಟು ತಂಪಾಗಿರುತ್ತದೆ. ಬೆಚ್ಚಗೆ ಮಾಡುವ ಮಳೆಯ ಋತುವಿನ ಅವಧಿಯಲ್ಲಿ ಕ್ವೀನ್ಸ್ಲೆಂಡ್ನ ಉತ್ತರಭಾಗದದಿಂದ ದಕ್ಷಿಣದ ದ್ವೀಪಕ್ಕೆ ಈ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಅವಶ್ಯವಾಗಿ ವಲಸೆಹೋಗುತ್ತಿದ್ದವು ಮತ್ತು ಕಾಲೋಚಿತ ತಾಪಮಾನ ಕುಸಿತದ ನಂತರ ಉತ್ತರ ಭಾಗಕ್ಕೆ ಸಂಭಾವ್ಯವಾಗಿ ಮರಳುತ್ತಿದ್ದವು ಎಂಬುದು ಪತ್ತೆಯಾಯಿತು. ಫ್ರೇಸರ್ ದ್ವೀಪ ಸಾರ್ವಜನಿಕರಲ್ಲಿ ಕಂಡುಬರುತ್ತಿದ್ದ ಅಚ್ಚರಿ ಮತ್ತು ಆಘಾತದ ಹೊರತಾಗಿಯೂ, ಇದು ಕಣ್ಣಿಗೆ ಕಾಣುವಂತೆ ಹೊಸ ವರ್ತನೆಯಾಗಿರಲಿಲ್ಲ ಹಾಗೂ ಬಹಳ ಹಿಂದಿನ ಕಾಲದಲ್ಲಿ, ಬೆಚ್ಚಗೆ ಮಾಡುವ ಮಳೆಯ ಋತುವಿನ ಅವಧಿಯಲ್ಲಿ, ಬ್ರಿಸ್ಬೇನ್ನಷ್ಟು ದೂರದ ದಕ್ಷಿಣ ಪ್ರದೇಶದಲ್ಲಿ ಕಾಡು ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಸಾಂದರ್ಭಿಕವಾಗಿ ಕಾಣಿಸುತ್ತಿದ್ದವು ಎಂದು ವರದಿಯಾಗಿತ್ತು.

ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ವಿಪರೀತಕಾವಿನ ಮಳೆಯ ಋತುವನ್ನು ಸಿಹಿನೀರಿನ ಜವುಗು ಪ್ರದೇಶಗಳು ಮತ್ತು ನದಿಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಸಾಮಾನ್ಯವಾಗಿ ಕಳೆಯುತ್ತವೆ; ಶುಷ್ಕ ಋತುವಿನಲ್ಲಿ ಅವು ನದಿಯ ಹರಿವಿನ ದಿಕ್ಕಿನಲ್ಲಿ ನದೀಮುಖಗಳಿಗೆ ಚಲಿಸುತ್ತವೆ ಮತ್ತು ಕೆಲವೊಮ್ಮೆ ಬಹಳ ದೂರಕ್ಕೆ ಸಮುದ್ರದೆಡೆಗೆ ಸಂಚರಿಸುತ್ತವೆ. ಅಸ್ತಿತ್ವದ ಪ್ರದೇಶಕ್ಕಾಗಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಪರಸ್ಪರರೊಂದಿಗೆ ಉಗ್ರವಾಗಿ ಪೈಪೋಟಿ ನಡೆಸುತ್ತವೆ; ಅದರಲ್ಲೂ ನಿರ್ದಿಷ್ಟವಾಗಿ, ಶಕ್ತಿಯುತ ಗಂಡು ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಸಿಹಿನೀರಿನ ತೊರೆಗಳು ಮತ್ತು ಹೊಳೆಗಳ ಅತ್ಯಂತ ಯೋಗ್ಯವಾದ ವಿಸ್ತರಣಗಳನ್ನು ಆಕ್ರಮಿಸಿಕೊಳ್ಳುತ್ತವೆ. ಈ ರೀತಿಯಾಗಿ ಕಿರಿಯ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಎಲ್ಲೆಗೆ ಅತಿ ಸಮೀಪವಿರುವ ನದಿ ವ್ಯವಸ್ಥೆಗಳಿಗೆ ಮತ್ತು ಕೆಲವೊಮ್ಮೆ ಸಾಗರದೊಳಗೆ ತಳ್ಳಲ್ಪಡುತ್ತವೆ. ಈ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಯ ವಿಸ್ತೃತ ಹರಡಿಕೆಯನ್ನು (ಭಾರತದ ಪೂರ್ವ ಕರಾವಳಿಯಿಂದ ಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾದ ಉತ್ತರಭಾಗದವರೆಗೆ ವ್ಯಾಪಿಸುವಿಕೆ) ಮಾತ್ರವೇ ಅಲ್ಲದೇ ಒಮ್ಮೊಮ್ಮೆ ಊಹಿಸಲಾಗದ ಸ್ಥಳಗಳಲ್ಲಿನ (ಜಪಾನ್ನ ಸಮುದ್ರದಂಥದು) ಕಾಣಿಸಿಕೊಳ್ಳುವಿಕೆಯನ್ನೂ ಇದು ವಿವರಿಸುತ್ತದೆ. ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಕ್ಲುಪ್ತವಾದ ಕ್ಷಣಕಾಲದ ರಭಸಗಳಲ್ಲಿ 15 to 18 miles per hour (6.7 to 8.0 m/s)ನಷ್ಟು ಈಜಬಲ್ಲವು, ಆದರೆ ಸಾಧಾರಣ ವೇಗದಲ್ಲಿ ಚಲಿಸುವಾಗ 2 to 3 mph (0.9 to 1.3 m/s)ನಷ್ಟು ಚಲಿಸುತ್ತವೆ.

ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಯು ಸಮಯಸಾಧಕತನದ ಒಂದು ಪರಮಾವಧಿಯ ಪರಭಕ್ಷಕನಾಗಿದ್ದು, ನೀರಿನಲ್ಲಿನ ಅಥವಾ ಶುಷ್ಕ ಭೂಮಿಯ ಮೇಲಿನ ತನ್ನ ಪ್ರದೇಶವನ್ನು ಪ್ರವೇಶಿಸುವ ಬಹುತೇಕವಾಗಿ ಯಾವುದೇ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಯನ್ನು ಎಳೆದುಕೊಂಡು ಹೋಗುವಷ್ಟು ಸಮರ್ಥವಾಗಿರುತ್ತದೆ. ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳ ಪ್ರಾಣಿ ಪ್ರದೇಶಕ್ಕೆ ಪ್ರವೇಶಿಸುವ ಮಾನವರ ಮೇಲೆ ಅವು ದಾಳಿಮಾಡುವುದು ಚಿರಪರಿಚಿತ ಸಂಗತಿಯೇ ಆಗಿದೆ. ಎಳೆ ಹರೆಯದ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಸಣ್ಣ ಗಾತ್ರದ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳ ಮೇಲೆ ಮಾತ್ರವೇ ದಾಳಿಮಾಡುತ್ತವೆ. ಅವುಗಳೆಂದರೆ, ಕೀಟಗಳು, ನೆಲೆಜಲವಾಸಿಗಳು, ಕಠಿಣಚರ್ಮಿಗಳು, ಸಣ್ಣ ಸರೀಸೃಪಗಳು, ಮತ್ತು ಮೀನುಗಳು. ಮೊಸಳೆಯ ದೊಡ್ಡದಾದಷ್ಟೂ ಅದು ತನ್ನ ಆಹಾರಕ್ರಮದಲ್ಲಿ ಸೇರ್ಪಡೆಮಾಡಿಕೊಳ್ಳುವ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳ ವೈವಿಧ್ಯತೆಯು ಮಹತ್ತರವಾಗಿರುತ್ತದೆಯಾದರೂ, ತುಲನಾತ್ಮಕವಾಗಿ ಸಣ್ಣಗಾತ್ರದಲ್ಲಿರುವ ಬೇಟೆಯು ವಯಸ್ಕ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳಲ್ಲಿಯೂ ಸಹ ಆಹಾರಕ್ರಮದ ಒಂದು ಪ್ರಮುಖ ಭಾಗವೆನಿಸಿಕೊಳ್ಳುತ್ತದೆ. ದೊಡ್ಡದಾದ ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ವಯಸ್ಕ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ತಮ್ಮ ವ್ಯಾಪ್ತಿಯೊಳಗೆ ಬರುವ ಯಾವುದೇ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳನ್ನು ಸಮರ್ಥವಾಗಿ ತಿನ್ನಬಲ್ಲವು. ಅಂಥ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳೆಂದರೆ: ಕೋತಿಗಳು, ಕಾಂಗರೂಗಳು, ಕಾಡು ಹಂದಿ, ಕಾಡುನಾಯಿಗಳು, ವರನಸ್ ಕುಲದ ದೊಡ್ಡ ಹಲ್ಲಿಗಳು, ಪಕ್ಷಿಗಳು, ಸಾಕಿದ ಜಾನುವಾರು, ಮುದ್ದಿನ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳು, ಮಾನವರು, ನೀರೆಮ್ಮೆ, ವನವೃಷಭಗಳು, ಬಾವಲಿಗಳು, ಮತ್ತು ಅಷ್ಟೇ ಏಕೆ ಶಾರ್ಕ್ಗಳೂ ಸಹ ಈ ಪಟ್ಟಿಯಲ್ಲಿ ಸೇರಿವೆ.[೧೦][೧೯][೨೦][೨೧] ಒಂದು ಟನ್ನಿಗಿಂತಲೂ ಹೆಚ್ಚು ತೂಗುವ ಸಾಕಿದ ದನ, ಕುದುರೆಗಳು, ನೀರೆಮ್ಮೆ, ಮತ್ತು ವನವೃಷಭ ಇವೇ ಮೊದಲಾದ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳು ಅತಿದೊಡ್ಡ ಬೇಟೆ ಎಂದು ಪರಿಗಣಿಸಲ್ಪಟ್ಟಿದ್ದು, ಗಂಡು ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಇವನ್ನು ಸರಾಗವಾಗಿ ಎಳೆದುಕೊಂಡು ಹೋಗುತ್ತವೆ. ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಯು ಸಾಮಾನ್ಯವಾಗಿ ಅತ್ಯಂತ ಆಲಸಿಯಾಗಿರುತ್ತದೆ; ಕೆಲವೊಮ್ಮೆ ಆಹಾರವಿಲ್ಲದೆಯೇ ತಿಂಗಳುಗಟ್ಟಲೇ ಅದು ಉಳಿದಿರುವಲ್ಲಿ ಈ ವಿಶೇಷ ಲಕ್ಷಣವು ನೆರವಾಗುತ್ತದೆ. ತನ್ನ ಜಡಸ್ವಭಾವದಿಂದಾಗಿ ಇದು ಸೋಮಾರಿಯಂತೆ ನೀರಿನಲ್ಲಿ ಅಲ್ಲಲ್ಲೇ ಸುತ್ತಾಡುತ್ತಾ ವಿಶಿಷ್ಟವಾಗಿ ಕಾಲ ಕಳೆಯುತ್ತದೆ ಅಥವಾ ದಿನದ ಬಹುಭಾಗದಲ್ಲಿ ಸೂರ್ಯನ ಬೆಳಕಿನಲ್ಲಿ ಬಿಸಿಲು ಕಾಯಿಸಿಕೊಳ್ಳುತ್ತದೆ, ಮತ್ತು ರಾತ್ರಿ ವೇಳೆಯಲ್ಲಿ ಬೇಟೆಯಾಡುವುದಕ್ಕೆ ಆದ್ಯತೆ ನೀಡುತ್ತದೆ. ನೀರಿನಲ್ಲಿದ್ದುಕೊಂಡು ಅಲ್ಲಿಂದ ಒಂದು ದಾಳಿಗೆ ಚಾಲನೆ ನೀಡುವ ಸಂದರ್ಭ ಬಂದಾಗ, ಸ್ಫೋಟಕವೆಂಬಂಥ ವೇಗದ ಕ್ಷಣಕಾಲದ ರಭಸಗಳನ್ನು ಹೊಮ್ಮಿಸುವ ಸಾಮರ್ಥ್ಯವನ್ನು ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಹೊಂದಿರುತ್ತವೆ. ಮೈದಾನದಲ್ಲಿನ ಅಲ್ಪ ಅಂತರಗಳನ್ನು ದಾಟುವ ಸಂದರ್ಭದಲ್ಲಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಒಂದು ರೇಸಿನ ಕುದುರೆಗಿಂತಲೂ ವೇಗವಾಗಿರುತ್ತವೆ ಎಂಬಂಥ ಕಥೆಗಳು ನಗರ ಪ್ರದೇಶದ ದಂತಕಥೆಗಿಂತಲೂ ಸ್ವಲ್ಪವೇ ಹೆಚ್ಚೆನಿಸುತ್ತದೆ. ಆದಾಗ್ಯೂ, ಪಾದಗಳು ಮತ್ತು ಬಾಲ ಈ ಎರಡರಿಂದಲೂ ಮುನ್ನೂಕುವಿಕೆಯನ್ನು ಅವು ಸಂಯೋಜಿಸಬಲ್ಲಂಥ ನೀರಿನ ಅಂಚಿನಲ್ಲಿ, ಪ್ರತ್ಯಕ್ಷದರ್ಶಿ ದಾಖಲೆಗಳು ಅಪರೂಪವಾಗಿವೆ.

ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಯು ದಾಳಿಮಾಡುವುದಕ್ಕೆ ಮುಂಚಿತವಾಗಿ ತನ್ನ ಬೇಟೆಯು ನೀರಿನ ಅಂಚಿಗೆ ನಿಕಟವಾಗಿ ಬರಲಿ ಎಂದು ಸಾಮಾನ್ಯವಾಗಿ ಕಾಯುತ್ತದೆ; ನಂತರ ಬೇಟೆಯನ್ನು ನೀರಿಗೆ ಮರಳಿ ಎಳೆದುಕೊಂಡು ಹೋಗುವಲ್ಲಿ ಅದರ ಮಹಾನ್ ಬಲವು ಈ ನಿಟ್ಟಿನಲ್ಲಿ ಅದಕ್ಕೆ ನೆರವಾಗುತ್ತದೆ. ಬಹುತೇಕ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳು ಮೊಸಳೆಯು ಹೊಂದಿರುವ ಮಹತ್ತರವಾದ ದವಡೆಯ ಒತ್ತಡದಿಂದಲೇ ಸಾಯಿಸಲ್ಪಡುತ್ತವೆಯಾದರೂ, ಕೆಲವೊಂದು ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳನ್ನು ಮೊಸಳೆಯು ಪ್ರಾಸಂಗಿಕವಾಗಿ ಮುಳುಗಿಸಿ ಉಸಿರುಕಟ್ಟಿ ಸಾಯಿಸುತ್ತದೆ. ಇದೊಂದು ಶಕ್ತಿಯುತ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಯಾಗಿದ್ದು, ಸಂಪೂರ್ಣವಾಗಿ ಬೆಳೆದ ನೀರೆಮ್ಮೆಯೊಂದನ್ನು ಒಂದು ನದಿಯೊಳಗೆ ಎಳೆದುಕೊಂಡು ಹೋಗುವುದಕ್ಕೆ ಬೇಕಿರುವ ಬಲವನ್ನು ಹೊಂದಿರುತ್ತದೆ, ಅಥವಾ ಸಂಪೂರ್ಣವಾಗಿ-ಬೆಳೆದ ಕಾಡೆತ್ತಿನ ತಲೆಬುರುಡೆಯನ್ನು ತನ್ನ ದವಡೆಗಳ ನಡುವೆ ಸಿಕ್ಕಿಸಿಕೊಂಡು ಪುಡಿಮಾಡಬಲ್ಲ ಸಾಮರ್ಥ್ಯವನ್ನು ಹೊಂದಿರುತ್ತದೆ. ವಿಶಿಷ್ಟವೆನಿಸಿರುವ ಇದರ ಬೇಟೆಯಾಡುವಿಕೆಯ ಕೌಶಲವು "ಸಾವಿನ ಉರುಳಾಟ" ಎಂದು ಕರೆಯಲ್ಪಟ್ಟಿದೆ: ಪ್ರಾಣಿಯ ಮೇಲೆ ಗಬಕ್ಕನೇ ಹಾರಿ ಇದು ಥಟ್ಟನೆ ಹಿಡಿದುಕೊಳ್ಳುತ್ತದೆ ಹಾಗೂ ಶಕ್ತಿಯುತವಾಗಿ ಅದನ್ನು ಸುರಳಿ ಸುತ್ತಿದಂತೆ ಸುತ್ತಿ ಉರುಳಿಸುತ್ತದೆ. ಇದರಿಂದಾಗಿ, ಹೆಣಗಾಡುತ್ತಿರುವ ಯಾವುದೇ ದೊಡ್ಡದಾದ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಯು ತನ್ನ ಸಮತೋಲನವನ್ನು ಕಳೆದುಕೊಳ್ಳುವಂತಾಗುತ್ತದೆ ಮತ್ತು ಆ ಬೇಟೆಯನ್ನು ನೀರಿನೊಳಗೆ ಎಳೆದುಕೊಂಡು ಹೋಗುವ ಕಾರ್ಯವು ಸರಾಗವಾಗಿ ಪರಿಣಮಿಸುತ್ತದೆ. ದೊಡ್ಡಗಾತ್ರದ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳು ಸತ್ತ ನಂತರ ಅವನ್ನು ಹರಿದು ಚಿಂದಿಮಾಡುವುದಕ್ಕಾಗಿಯೂ ಈ "ಸಾವಿನ ಉರುಳಾಟ"ದ ತಂತ್ರವು ಬಳಸಲ್ಪಡುತ್ತದೆ.

ಮೊಸಳೆ ಸೂಚಕ ಹಲ್ಲಿಗಳು, ಪರಭಕ್ಷಕ ಮೀನುಗಳು, ಪಕ್ಷಿಗಳು, ಮತ್ತು ಇತರ ಅನೇಕ ಪರಭಕ್ಷಕ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳಿಗೆ ಎಳೆಯವಯಸ್ಸಿನ ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಬೇಟೆಯಾಗಿ ಸಿಕ್ಕಿಬೀಳಬಹುದು. ಎಳೆ ಹರೆಯದ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಕೂಡಾ ಅವುಗಳ ವ್ಯಾಪ್ತಿಯಲ್ಲಿನ ನಿಶ್ಚಿತ ಭಾಗಗಳಲ್ಲಿರುವ ಬಂಗಾಳ ಹುಲಿಗಳು ಮತ್ತು ಚಿರತೆಗಳಿಗೆ ಬೇಟೆಯಾಗಿ ಸಿಕ್ಕಿಬೀಳಬಹುದಾದರೂ, ಇದು ಅಪರೂಪವೆನಿಕೊಂಡಿದೆ.

ಡಾ. ಆಡಂ ಬ್ರಿಟನ್[೨೨] ಎಂಬ ಓರ್ವ ಸಂಶೋಧಕನು ಮೊಸಳೆ ಜಾತಿಗೆ ಸೇರಿದ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳ ಬುದ್ಧಿಸೂಕ್ಷ್ಮತೆಯ ಕುರಿತು ಅಧ್ಯಯನ ಮಾಡುತ್ತಿದ್ದಾನೆ. ಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾದ ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳ ಕೂಗುವಿಕೆಗಳ[೨೩] ಒಂದು ಸಂಗ್ರಹವನ್ನು ಅವನು ಸಂಕಲಿಸಿದ್ದು, ಅವುಗಳಿಗೂ ಮತ್ತು ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳ ವರ್ತನೆಗಳಿಗೂ ಅವನು ಈ ಮೂಲಕ ಸಂಬಂಧ ಕಲ್ಪಿಸಿದ್ದಾನೆ. ಸಸ್ತನಿಗಳ ಮಿದುಳುಗಳ ಗಾತ್ರಕ್ಕಿಂತಲೂ ಮೊಸಳೆ ಜಾತಿಗೆ ಸೇರಿದ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳ ಮಿದುಳುಗಳು ಬಹಳಷ್ಟು ಸಣ್ಣವಾಗಿದ್ದರೂ ಸಹ (ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಯಲ್ಲಿ ಶರೀರ ತೂಕದ 0.05%ನಷ್ಟು ಇರುತ್ತದೆ), ಅತ್ಯಂತ ಅಲ್ಪಪ್ರಮಾಣದಲ್ಲಿ ರೂಢಿಮಾಡಿಸಿದರೂ ಕಷ್ಟಕರವಾದ ಕಾರ್ಯಭಾರಗಳನ್ನು ಅವು ಕಲಿಯಬಲ್ಲವಾಗಿವೆ ಎಂಬುದು ಅವನ ನಿಲುವಾಗಿದೆ. ಮೊಸಳೆಯ ಕೂಗುವಿಕೆಗಳು ಪ್ರಸಕ್ತವಾಗಿ ಅಂಗೀಕರಿಸಲ್ಪಟ್ಟ ಪ್ರಮಾಣಕ್ಕಿಂತ ಆಳವಾಗಿರುವ ಒಂದು ಭಾಷಾ ಸಾಮರ್ಥ್ಯವನ್ನು ಅದು ಹೊಂದಿರುವುದರ ಸುಳುಹನ್ನು ನೀಡುತ್ತದೆ ಎಂಬುದು ಅವನ ತೀರ್ಮಾನವಾಗಿದೆ. ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಬುದ್ಧಿವಂತ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳಾಗಿದ್ದು ಪ್ರಯೋಗಗಳಿಗೆ ಒಳಪಡಿಸುವ ಇಲಿಗಳಿಗಿಂತಲೂ ಪ್ರಾಯಶಃ ಹೆಚ್ಚು ವೇಗವಾಗಿ ಅವು ಕಲಿಯುತ್ತವೆ ಎಂದು ಅವನು ಸೂಚಿಸುತ್ತಾನೆ. ಋತುಗಳು ಬದಲಾಗುತ್ತಿದ್ದಂತೆ ಬದಲಾಗುವ ತಮ್ಮ ಬೇಟೆಯ ವಲಸೆಯ ಮಾರ್ಗವನ್ನು ಜಾಡುಹಿಡಿಯುವ ಕಲೆಯನ್ನೂ ಅವು ಸಿದ್ಧಿಸಿಕೊಂಡಿವೆ.

ದಾಳಿಗಳ ಕುರಿತಾದ ಮಾಹಿತಿಯು ಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾದ ಹೊರಭಾಗಕ್ಕೆ ಸೀಮಿತವಾಗಿದೆ. ಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾದಲ್ಲಿ ದಾಳಿಗಳು ಅಪರೂಪವಾಗಿದ್ದು, ಅವು ಸಂಭವಿಸಿದಾಗ ರಾಷ್ಟ್ರೀಯ ಸುದ್ದಿ ಪ್ರಕಟಣೆಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಸಾಮಾನ್ಯವಾಗಿ ಕಾಣಿಸುತ್ತವೆ. ದೇಶದಲ್ಲಿ ಪ್ರತಿ ವರ್ಷ ಸರಿಸುಮಾರಾಗಿ ಒಂದರಿಂದ ಎರಡು ಮಾರಣಾಂತಿಕ ದಾಳಿಗಳು ವರದಿಯಾಗುತ್ತವೆ.[೨೪] ಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾದಲ್ಲಿನ ವನ್ಯಜೀವಿಕುಲ ಇಲಾಖೆಯ ಅಧಿಕಾರಿಗಳು ಅಪಾಯದ ತಾಣಗಳೆನಿಸಿರುವ ಅನೇಕ ತುಂಡುತೊರೆಗಳು, ನದಿಗಳು, ಸರೋವರಗಳು ಮತ್ತು ಸಮುದ್ರ ತೀರಗಳ ಪ್ರದೇಶದಲ್ಲಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಯಿರುವುದರ ಕುರಿತಾದ ಎಚ್ಚರಿಕೆ ಚಿಹ್ನೆಗಳನ್ನು ಲಗತ್ತಿಸುವ ಮೂಲಕ ವ್ಯಾಪಕ ಪ್ರಯತ್ನಗಳನ್ನು ಕೈಗೊಳ್ಳುತ್ತಿರುವುದರಿಂದಾಗಿ ದಾಳಿಗಳ ಮಟ್ಟವು ತಗ್ಗಿರಬಹುದು. ಆರ್ನ್ಹೆಮ್ ಲ್ಯಾಂಡ್ನ ದೊಡ್ಡ ಮೂಲನಿವಾಸಿ ಸಮುದಾಯದಲ್ಲಿ ದಾಳಿಗಳು ವರದಿಮಾಡಲ್ಪಡದಿರುವ ಸಾಧ್ಯತೆಗಳಿವೆ. ಬೋರ್ನಿಯೊ,[೨೫] ಸುಮಾತ್ರಾ,[೨೬] ಭಾರತದ ಪೂರ್ವಭಾಗ (ಅಂಡಮಾನ್ ದ್ವೀಪಗಳಲ್ಲಿ),[೨೭][೨೮] ಮತ್ತು ಮ್ಯಾನ್ಮಾರ್ನಲ್ಲಿ ಇತ್ತೀಚೆಗೆ ದಾಳಿಗಳು ಸಂಭವಿಸಿವೆಯಾದರೂ ಅದು ಅಷ್ಟಾಗಿ ಬಹಿರಂಗಗೊಂಡಿಲ್ಲ.[೨೯]

1945ರ ಫೆಬ್ರುವರಿ 19ರಂದು, ರಾಮ್ರೀ ದ್ವೀಪದ ಕದನದಲ್ಲಿ ಜಪಾನಿಯರನ್ನು ಹಿಮ್ಮೆಟ್ಟಿಸುವ ಸಂದರ್ಭದಲ್ಲಿ ಸಂಭವಿಸಿದ 400 ಮಂದಿ ಜಪಾನಿ ಸೈನಿಕರ ಸಾವುಗಳಿಗೆ ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳು ಹೊಣೆಗಾರರಾಗಿರಬಹುದು ಎಂದು ಭಾವಿಸಲಾಗಿದೆ. ಜಪಾನಿ ಸೈನಿಕರು ಹಿಮ್ಮೆಟ್ಟುವಾಗ ತೂರಿಕೊಂಡ ಜವುಗು ಪ್ರದೇಶವನ್ನು ಬ್ರಿಟಿಷ್ ಸೈನಿಕರು ಸುತ್ತುವರೆದಾಗ, ಜಪಾನಿ ಸೈನಿಕರು ಒಂದು ರಾತ್ರಿಯ ಮಟ್ಟಿಗೆ ಮ್ಯಾಂಗ್ರೋವ್ಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಉಳಿಯಬೇಕಾಗಿ ಬಂತು; ಇದು ಸಾವಿರಾರು ಸಂಖ್ಯೆಯ ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆಗಳ ಆವಾಸಸ್ಥಾನವಾಗಿತ್ತು. ಗಿನ್ನೆಸ್ ದಾಖಲೆಗಳ ಪುಸ್ತಕದಲ್ಲಿ[೩೦] "ದಿ ಗ್ರೇಟೆಸ್ಟ್ ಡಿಸಾಸ್ಟರ್ ಸಫರ್ಡ್ ಫ್ರಂ ಅನಿಮಲ್ಸ್" ಎಂಬ ತಲೆಬರಹದ ಅಡಿಯಲ್ಲಿ ರಾಮ್ರೀ ಮೊಸಳೆ ದಾಳಿಗಳು ಪಟ್ಟಿಮಾಡಲ್ಪಟ್ಟಿವೆ.

|isbn= value: invalid character (help). ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಅಥವಾ ನದೀಮುಖದಲ್ಲಿರುವ ಮೊಸಳೆ ಯು (ಕ್ರಾಕಡೈಲಸ್ ಪೋರೋಸಸ್ ) ಎಲ್ಲಾ ಜೀವಂತ ಸರೀಸೃಪಗಳ ಪೈಕಿ ಅತಿದೊಡ್ಡದು ಎನಿಸಿಕೊಂಡಿದೆ. ಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾದ ಉತ್ತರಭಾಗ, ಭಾರತದ ಪೂರ್ವಭಾಗದ ಕರಾವಳಿ ಮತ್ತು ಆಗ್ನೇಯ ಏಷ್ಯಾದ ಭಾಗಗಳಲ್ಲಿನ ತನಗೆ ಸರಿಹೊಂದುವ ಆವಾಸಸ್ಥಾನಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಇದು ಕಂಡುಬರುತ್ತದೆ. ತಾನು ವಾಸಿಸುವಪ್ರದೇಶಗಳ ಸುತ್ತ ಮುತ್ತ ವಾಸಿಸುವ ಮನುಷ್ಯರ ಪಾಲಿಗೆ ಸಮುದ್ರವಾಸಿ ಮೊಸಳೆ ಅತ್ಯಂತ ಅಪಾಯಕಾರಿ ಎನ್ನಲಾಗಿದೆ. ಮನುಷ್ಯರನ್ನು ಕೊಂದು ತಿಂದ ಹಲವು ಘಟನೆಗಳು ಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾದ ಕ್ವೀನ್ಸ್ಲೆಂಡ್, ನಾರ್ದರ್ನ್ ಟೆರಿಟರಿ ಹಾಗೂ ವೆಸ್ಟರ್ನಆಸ್ಟ್ರೇಲಿಯಾ ರಾಜ್ಯಗಳ ಉತ್ತರ ಕಡಲತೀರ ಪ್ರದೇಶಗಳಿಂದ ವರದಿಗಳು ಬಂದದ್ದುಂಟು.

Al cocodréll marèin (Crocodylus porosus, Schneider 1801) l'è al pió grôs cocodréll vivèint, cun 'na lunghèża màsima ażertèda ed 6,3 méter e 'na lunghèza màsima prubàbil ed pió ed 7 mèter; tòttavia, l'è prubàbil c'agh sìen anch d'i esemplèri lónghi pió ed 8 mèter.

Al pês al pò tuchêr e superêr la tunelèda. In generêl, i mâs'c lónghi pió ed 6 mèter, i én di mòndi rèri. I fèmni i crássen ed méno (in mèdia 2 o 3 mèter).

Al cocodréll marèin al vîv prevalentemèint in d'al mêr e in d'i estuàri d'i fiómm. La diéta l'e piutòst vèria: i żôven i màgnen insètt, páss e luzértli; i adùlti i préden gròsi erbìvori, gròsi páss e, d'al vòlti, anch animèli da bestiâm.

Al cocodréll marèin (Crocodylus porosus, Schneider 1801) l'è al pió grôs cocodréll vivèint, cun 'na lunghèża màsima ażertèda ed 6,3 méter e 'na lunghèza màsima prubàbil ed pió ed 7 mèter; tòttavia, l'è prubàbil c'agh sìen anch d'i esemplèri lónghi pió ed 8 mèter.

Al pês al pò tuchêr e superêr la tunelèda. In generêl, i mâs'c lónghi pió ed 6 mèter, i én di mòndi rèri. I fèmni i crássen ed méno (in mèdia 2 o 3 mèter).

Al cocodréll marèin al vîv prevalentemèint in d'al mêr e in d'i estuàri d'i fiómm. La diéta l'e piutòst vèria: i żôven i màgnen insètt, páss e luzértli; i adùlti i préden gròsi erbìvori, gròsi páss e, d'al vòlti, anch animèli da bestiâm.

The saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) is a crocodilian native to saltwater habitats, brackish wetlands and freshwater rivers from India's east coast across Southeast Asia and the Sundaic region to northern Australia and Micronesia. It has been listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List since 1996.[2] It was hunted for its skin throughout its range up to the 1970s, and is threatened by illegal killing and habitat loss. It is regarded as dangerous to humans.[4]

The saltwater crocodile is considered to be the largest living reptile.[5][6][7] Males can grow up to a length of 6 m (20 ft), rarely exceeding 6.3 m (21 ft), and a weight of 1,000–1,500 kg (2,200–3,300 lb).[8][9][10][11] Females are much smaller and rarely surpass 3 m (10 ft).[12][13] It is also called the estuarine crocodile, Indo-Pacific crocodile, marine crocodile, sea crocodile, and, informally, the saltie.[14] A large and opportunistic hypercarnivorous apex predator, they ambush most of their prey and then drown or swallow it whole. They will prey on almost any animal that enters their territory, including other predators such as sharks, varieties of freshwater and saltwater fish including pelagic species, invertebrates such as crustaceans, various amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, including humans.[15][16]

Crocodilus porosus was the scientific name proposed by Johann Gottlob Theaenus Schneider who described a zoological specimen in 1801.[17] In the 19th and 20th centuries, several saltwater crocodile specimens were described with the following names:

Currently, the saltwater crocodile is considered a monotypic species.[24] However, based largely on morphological variability, it is thought possible that the taxon C. porosus comprises a species complex. Borneo crocodile C. raninus specimens can reliably be distinguished both from saltwater and Siamese crocodiles (C. siamensis) on the basis of the number of ventral scales and on the presence of four postoccipital scutes, which are often absent in true saltwater crocodiles.[25][26]

Fossil remains of a saltwater crocodile excavated in northern Queensland were dated to the Pliocene.[27][28] The saltwater crocodile's closest extant (living) relatives are the Siamese crocodile and the mugger crocodile.[29][30][31][32]

The genus Crocodylus likely originated in Africa and radiated outwards towards Southeast Asia and the Americas,[32] although an Australian/Asian origin has also been considered.[33] Phylogenetic evidence supports Crocodylus diverging from its closest recent relative, the extinct Voay of Madagascar, around 25 million years ago, near the Oligocene/Miocene boundary.[32]

Below is a cladogram based on a 2018 tip dating study by Lee & Yates simultaneously using morphological, molecular (DNA sequencing), and stratigraphic (fossil age) data,[31] as revised by the 2021 Hekkala et al. paleogenomics study using DNA extracted from the extinct Voay.[32]

CrocodylinaeVoay†

CrocodylusCrocodylus Tirari Desert†

Asia+AustraliaCrocodylus johnstoni Freshwater crocodile ![]()

Crocodylus novaeguineae New Guinea crocodile

Crocodylus mindorensis Philippine crocodile

Crocodylus porosus Saltwater crocodile ![]()

Crocodylus siamensis Siamese crocodile ![]()