pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

Antarctic minke whales feed mainly on krill (Euphausia superba). Euphausia superba comprises 100% of stomach contents of minke whales caught at the ice edge and 94% (by weight) of the stomach contents of minke whales in the offshore zone. Euphausia crystarollophias was also found in smaller quantities in the stomachs of Antarctic minke whales caught in coastal areas. Other prey include Euphasi frigida and Thysanoessa macrura. This is in contrast to common minke whales, which feed on a more diverse array of fish and invertebrates. Antarctic minke whales feed primarily in the early morning and late evening and most feeding activity is observed at the edge of pack ice. Daily food consumption in the summer was estimated at 3.6 to 5.3% of body weight, representing an important proportion of krill biomass in the study area. It is likely that Antarctic minke whales eat much smaller quantities of food during the austral winter or perhaps forage very little at all on wintering grounds (Best 1982 as cited in Reilly et al., 2008). The blubber layer thickens as the feeding season progresses but mean blubber thickness in individuals has decreased over the 18 year period between 1987 and 2005. This might suggest a decrease in food availability in Antarctic waters.

Animal Foods: aquatic crustaceans; zooplankton

Foraging Behavior: filter-feeding

Primary Diet: carnivore (Eats non-insect arthropods); planktivore

Antarctic minke whales used to be considered a subspecies of Balaenoptera acutorostrata, B. a. bonaerensis. In the late 1990s, however, it came to be recognized as a separate species, Balaenoptera bonaerensis (Burmeister, 1867). Phylogenetic analysis of the mitochondrial DNA control region led Àrnason et al. (1993) to elevate B. bonaerensis to full species status. Their analysis also led to the conclusion that B. bonaerensis and B. acutorostrata are sister taxa more closely related to each other than to any other species of the genus Balaenoptera.

Although the geographic ranges of both minke whale species overlap in the Southern Hemisphere, Balaenoptera bonaerensis is numerically dominant in high southern latitudes (south of 60ºS). By analysis of mitochondrial DNA, Pastene et al. (2007) estimated the divergence of B. acutorostrata and B. bonaerensis to have occurred about 5 million years ago in a period of global warming during the Pliocene.

A relatively large amount of research has been conducted on the reproductive biology of Antarctic minke whales. Tetsuka et al. (2004) found that there was a very high level of variation in the size of ovaries of the 94 immature females they captured. In addition, they found that ovarian size almost doubled during the prepubertal period. Over time, the developed ovary contains larger but less abundant follicles. Some researchers have even attempted to perform in vitro maturation of Antarctic minke whale oocytes (Iwayama et al., 2005).

Balaenoptera acutorostrata in the North Atlantic produces an extensive range of sounds. Mellinger and Carson (2000) analyzed pulse trains of minke whales in the Caribbean and classified them into two categories: the “speed-up” trains and the less common “slow-down” trains. Pulse trains are sequences of pulses produced at regular or irregular intervals. There is limited information, however, as to whether this type of vocalization is also present in B. bonaerensis and what function it serves in B. acutorostrata.

Communication Channels: acoustic

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; ultrasound ; chemical

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) currently lists the species as “Data Deficient”. However, it has been suggested that the species has declined by about 60% between the periods 1978–91 and 1991–2004. If the decline is shown to be an artifact or to have been transient, the species would then be classified as “Least Concern” whereas it would be classified as “Endangered” if it was demonstrated to be an actual decline. The Peru population was added to Appendix I of CITES in 1986 and withdrawn from it in 2001. The predicted substantial decline in the extent of Antarctic sea ice may dramatically effect krill populations and the Antarctic minke whale populations that depend on them.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: appendix i

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: data deficient

There are no recognized direct negative impacts of Antarctic minke whales on human populations. One could hypothesize, however, that potential food competition with other economically important whale species, such as blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus), could have a negative economic impact on their harvest. Larger whale species are considered more valuable in that they provide more meat per unit catch.

Since 1986, commercial whaling has been prohibited by the International Whaling Commision. Balaenoptera bonaerensis is currently taken for scientific whaling by the Japanese. The animals caught in that process can then be sold on the market for food. Before the decline of larger whale species, such as fin and blue whales (Balaenoptera physalus and Balaenoptera musculus, respectively), B. bonaerensis was rarely targeted by whalers due to its comparatively smaller size. Consequently, whaling on Antarctic minke whales has only started relatively recently, since 1971 (IWC 2006 as cited in Reilly et al., 2008).

Positive Impacts: food ; research and education

Antarctic minke whales are predators of krill, mainly Euphasia superba and are preyed on by killer whales (Orcinus orca). They may compete with other mammals and birds feeding on krill, such as penguins (Spheniscidae), crabeater seals (Lobodon carcinophaga), and blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus). Antarctic minke whales may also be the host of several types of microorganisms. For instance, they are often observed to have a film of diatoms on their skin. The extent of this film is thought to be correlated with the amount of time a whale has spent in cold waters.

Balaenoptera bonaerensis occurs in polar to tropical waters of the southern hemisphere. It occurs in large numbers south of 60º S, throughout the Antarctic. The distribution is more difficult to assess north of the Antarctic because of its co-occurrence with Balaenoptera acutorostrata. As a result, the boundaries of the species’ winter distributions remain largely undefined. Balaenoptera bonaerensis is observed off the coast of Brazil and South Africa and there have been occasional sightings in Peru. An unknown proportion of the species remains in Antarctic waters during the winter.

Biogeographic Regions: antarctica (Native ); indian ocean (Native ); atlantic ocean (Native ); pacific ocean (Native )

Balaenoptera bonaerensis can be found in marine waters from polar to tropical regions, generally within 160 km of the edge of pack ice. While mostly found at the ice edge, B. bonaerensis can also be found within the pack ice and in polynyas. Association with pack ice is especially pronounced during winter.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; tropical ; polar ; saltwater or marine

Aquatic Biomes: pelagic ; coastal

In an 18-year study of energy storage in Antarctic minke whales, Konishi et al. (2008) aged a total of 4,268 mature whales (mature males and pregnant females). They used measurement of the earplug, a layered keratinized and fatty structure inside the external auditory canal, to determine age. The oldest whale aged in their study was 73 years old according to this technique.

Range lifespan

Status: wild: 73 (high) years.

Antarctic minke whales seem to be the main prey for type-A killer whales in Antarctica (Orcinus orca). Antarctic minke whales also represent a large proportion of Japanese whaling catches and have become an increasingly important in recent years with the decline of larger Balaenoptera species populations.

Known Predators:

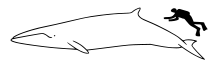

Balaenoptera bonaerensis is among the smallest rorqual species. Mature males average 8.36 m in length and weigh 6.85 tons, but they can reach a total length of 9.63 m and a weight of 11.05 tons. Females are slightly longer with a mean total length of 7.57 m and a maximum measured length of 10.22 m. On average, B. bonaerensis is slightly longer than all forms of B. acutorostrata. Similar to common minke whales, Antarctic minke whales are dark grey on the back with a pale ventral side. The main recognition character that allows for the distinction of Antarctic minke whales from common minke whales is the absence of a white patch on the flippers in Antarctic minke whales. The rostrum is narrow and pointed. The dorsal fin is hook-shaped and located about two-thirds the length of the body from the anterior. Baleen plates are black on the left side and on the posterior 2/3 of the right side, while the remaining baleen plates are white. The baleen plate filaments average about 3.0 mm in diameter. Antarctic minke whales have larger skulls than common minke whales.

Range length: 6.32 to 10.22 m.

Average length: Males: 8.36; Females:8.89 m.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: female larger

Lucena (2006) suggested that Antarctic minke whales are polygamous, judging by the structure of groups in breeding grounds. Little is known about mating behavior in any rorqual.

Mating System: polygynandrous (promiscuous)

Kasamatsu et al. (1995) found that minke whales (probably Balaenoptera bonaerensis) migrate far north but their main breeding areas are probably between 10º and 20º S. Breeding populations may be relatively dispersed and do not seem to be associated with the coast. The generation time is estimated to be about 22 years.

Antarctic minke whales, like common minke whales, have a gestation period of 10 months, after which a single young is born at about 2.7 meters long. Calves stay with their mother for up to 2 years and may nurse for 3 to 6 months.

In Antarctic minke whales, the age at which sexual maturity is reached has been shown to have decreased from an average of age 11 in the cohorts of 1950’s to about 7 years old in the 1970’s cohorts.

Breeding interval: Antarctic minke whale females can breed up to every year, although it is more common for them to breed less often.

Breeding season: It is thought that the breeding season occurs during the austral summer.

Average number of offspring: 1.

Average gestation period: 10 months.

Range weaning age: 3 to 6 months.

Range time to independence: 2 (high) years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 7 years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 7 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; viviparous

Female Antarctic minke whales gestate, nurse, and protect their young for up to two years. Males do not provide parental care. The milk of their close relatives, common minke whales (Balaenoptera acutorostrata), contains lactose and several other oligosaccharides, some of which have never been found in any other mammalian species. These new oligosaccharides may have a function in the immunity of the neonate.

Parental Investment: precocial ; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-independence (Protecting: Female)

Bio-duck is the nickname given to a strange, quack-like sound which has baffled researchers since the 1960s, when. the first bio-duck sounds were reported by sonar operators on Oberon class submarines.

New research has revealed"conclusive evidence"that the culprit behind these mysterious sounds is the Antarctic minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis).

Until recently, minke whales were considered as a single species, butmitochondrial DNA testinghas differentiated between the common minke whale and the Antarctic minke whale.

The Antarctic minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis)is the larger species of minke whale.However, in whale terms, they are still relatively small – usually less than 10 meters in length and weighing onaverage 9 tonnes.These whales can be found in all oceans in the southern hemisphere.

In the polar regions, they are commonly found within160 kmof pack ice especially during winter. Antarctic minke whales sometimes use their rostrum to break ice to create breathing holes.Most minke whales seem to migrate between summer and winter grounds but some populations appear to remain in Antarctic waters throughout the year.Population distribution north of Antarctica is difficult to assess as there is significant overlap with common minke whales.

Antarctic minke whales can be solitary or form small groups of2 – 4 individuals.Minke whales are notorious for their curiosity and are one of the most frequently observedBalaenopterabecause of their habit of approaching stationary boats.

Antarctic minke whales are baleen whales that feed primarily on Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba).Krill comprises 100% of stomach contents of Antarctic minke whales caught at the ice edge and 94% of the stomach contents of minke whales in the offshore zone.Feeding at the ice edge is more common in the early morning.

TheIUCN Red Listclassifies Antarctic minke whales as a data deficient species as there is no formal estimate of population abundance.

For more information on MammalMAP, visit the MammalMAPvirtual museumorblog.

Kiçik Cənub Zolaqlı balinası[2] (lat. Balaenoptera bonaerensis) — Zolaqlı balinalar fəsiləsinə aid balina növü.

Kiçik Cənub Zolaqlı balinası Zolaqlı və Bığlı balinalara daxil olan ən kiçik nümayyətdədir. Bu canlıların uzunluğu 7,2—10,7 metr, çəkisi isə 5,8 - 9,1 t arasında dəyişir. Orta ölçülü dişilər erkəklərdən bir metr iri olurlar. Yeni doğulan balaların uzunluğu 2,4—2,8 meyrdir.[3] Bel nahiyyəsi tünd-boz, qarın nahiyəsi isə ağ rəngdə olur.

Cənub yarımkürəsində yerləşən bütün okeanlarda yaşaya bilirlər. Yay ayları hətta Antarktida sahillərində belə görünürlər.

Kiçik Cənub Zolaqlı balinası (lat. Balaenoptera bonaerensis) — Zolaqlı balinalar fəsiləsinə aid balina növü.

Balaenoptera bonaerensis és una espècie de balena franca del subordre dels misticets. És un dels rorquals més petits i també una de les balenes més petites. Entre els rorquals, només el rorqual d'aleta blanca és més petit i entre les balenes també és més petita la balena franca pigmea també és més petita. La longitud és d'entre 7,2-10,7 metres i el pes varia entre 5,8-9,1 tones.[1] De mitjana, les femelles són aproxidament un metre més llargues que els mascles.[1] Les cries mesuren entre 2,4-2,8 meters.[1]

Balaenoptera bonaerensis és una espècie de balena franca del subordre dels misticets. És un dels rorquals més petits i també una de les balenes més petites. Entre els rorquals, només el rorqual d'aleta blanca és més petit i entre les balenes també és més petita la balena franca pigmea també és més petita. La longitud és d'entre 7,2-10,7 metres i el pes varia entre 5,8-9,1 tones. De mitjana, les femelles són aproxidament un metre més llargues que els mascles. Les cries mesuren entre 2,4-2,8 meters.

Plejtvák jižní (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) je druh plejtváka z podřádu kosticovců a čeledi plejtvákovitých, blízce příbuzný plejtváku malému (lat. Balaenoptera acutorostrata). Obývá vody jižní polokoule a poprvé byl přírodovědecky popsán v roce 1867. Dříve byl považován za poddruh plejtváka malého, ale po rozhodnutí Mezinárodní velrybářské komise (zkr. IWC, anglicky The International Whaling Commission) v červnu 2000 byly tyto dva druhy od sebe odděleny.[2]

Plejtvák jižní měří na délku 7,2 až 10,7 metrů a váží mezi 5,8 a 9,1 tunami. V průměru měří samice o metr víc než samci. Délka novorozených mláďat se pohybuje mezi 2,4 až 2,8 metry. Hřbet plejtváka jižního je tmavě šedý, zatímco jeho břicho je bílé.

Plejtvák jižní může vydávat zvuky podobné kachnám. Jeho zpěv, oceánografům známý již od 60. let 20. století, bývá pravidelně slyšet hydrofony umístěnými v chladných vodách Jižního oceánu. Až v roce 2013 byl ovšem zpěv přiřazen k tomuto druhu plejtváka. Zpočátku byl přisuzován ponorkám, ale jelikož byl zaznamenáván pouze v zimě a na jaře, došli vědci posléze k závěru, že se jedná o přírodní a sezónní jev. Mikrofony umístěny na dva jedince plejtváka jižního byly schopny zaregistrovat jejich zpěv, vydávaný většinou v blízkosti hladiny a často chvíli před potopením do hlubin.

Tloušťka vrstvy tuku těchto savců, měřena na více místech Jižního oceánu, slábne. Toto oslabení může poukazovat na zhoršující se zdravotní stav plejtváků nebo na problémy s výživou (například nedostatek krilu), protože tloušťka vrstvy tuku je považována za jeden z ukazatelů dobrého zdravotního stavu u velryb.

V tomto článku byl použit překlad textu z článku Petit rorqual de l'Antarctique na francouzské Wikipedii.

Plejtvák jižní (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) je druh plejtváka z podřádu kosticovců a čeledi plejtvákovitých, blízce příbuzný plejtváku malému (lat. Balaenoptera acutorostrata). Obývá vody jižní polokoule a poprvé byl přírodovědecky popsán v roce 1867. Dříve byl považován za poddruh plejtváka malého, ale po rozhodnutí Mezinárodní velrybářské komise (zkr. IWC, anglicky The International Whaling Commission) v červnu 2000 byly tyto dva druhy od sebe odděleny.

Der Südliche Zwergwal (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) ist eine Art der Furchenwale, die in den großen Weltmeeren auf der Südhemisphäre der Erde zwischen 20° und 65°S lebt.

Der Südliche Zwergwal wird 7,2 bis 10,7 Meter lang, 5,8 bis 9,1 t schwer und ist damit kräftiger und größer als der Nördliche Zwergwal. Weibchen können bis zu einen Meter länger werden als die Männchen. Der Körper ist schlank und stromlinienförmig, die auf dem hinteren Körperdrittel sitzende Finne relativ hoch, sichelförmig und beim Schwimmen nur kurz an der Wasseroberfläche sichtbar. Die Schnauze ist spitz, der Oberkiefer von oben gesehen dreieckig und trägt in der Mitte eine scharfe Rostrumleiste.

Der Rücken ist dunkelgraubraun, fast schwarz erscheinend, die Seiten blaugrau, der Bauch heller. Der Übergang zwischen dunklem Rücken und den Körperseiten ist wellenförmig und verschwommen. Hinter dem Kopf können sich oberhalb der Flipper einige helle Winkel zeigen, die in der Natur aber nur bei guter Sicht zu sehen sind. Die oberseits dunklen Flipper besitzen weiße Vorderkanten.

Die Barten des vorderen rechten Kiefers sind weiß, die übrigen Barten sind dunkel. Damit sind die Barten des Südlichen Zwergwals im Unterschied zu denen anderer Bartenwalen asymmetrisch gefärbt.

Der Südliche Zwergwal lebt auf der Südhalbkugel der Erde, vor allem zwischen 20° und 65°S. Die größten Bestände finden sich im Südatlantik und im südlichen Indischen Ozean, weniger häufig ist die Art im Südpazifik. Die Tiere wandern zwischen äquatornahen Regionen, wo sie sich vor allem in flachen Küstengewässern aufhalten und der Antarktis. Wahrscheinlich trennen sich die Geschlechter dabei zeitweise. Die Fortpflanzung findet im Winter zwischen 10° und 30°S statt. Im Sommer ziehen die Wale in die Futtergründe der Antarktis. Während einige Individuen sich dabei nur bis zum 42°S bewegen, wandern andere bis in das Rossmeer (72°S).

Der Südliche Zwergwal lebt einzeln oder in lockeren Gruppen, die manchmal hunderte von Tieren umfassen können. Er ernährt sich von pelagischen Krebstieren und von kleinen Schwarmfischen, in der Antarktis vor allem von Krill. Die lange Paarungszeit der Südlichen Zwergwale liegt im Südwinter und reicht von Juni bis Dezember (Kernzeit August bis September). Das Walkalb wird nach einer Tragzeit von etwa 14 Monaten mit einer Länge von 2,4 bis 2,8 Meter vom späten Mai bis August vor allem in wärmeren Gewässern geboren.

Beim Auftauchen der Südlichen Zwergwale erscheint zunächst der Kopf in einem niedrigen Winkel, dann der Blas. Die Finne wird erst nach dem Verschwinden des Blas sichtbar. Das Abtauchen geschieht mit einer hohen Rollbewegung. Vor dem tiefen Tauchen stellt sich der Südliche Zwergwal fast senkrecht und zeigt dabei Schwanzstiel und Finne, aber keinen Flukenschlag. Er kann mindestens 15 Minuten tauchen. Der Blas steigt senkrecht empor, ist säulenförmig, mittelhoch (2–3 Meter) und schwach aber gut sichtbar. Ein Wal bläst etwa 5 bis 8 Mal in Abständen von weniger als einer Minute. Gegenüber kleinen Booten ist der Südliche Zwergwal neugierig.

Der Südliche Zwergwal ist für das Bio-Duck-Geräusch verantwortlich, welches vorwiegend im südlichen Winter vorkommt. Dieses Geräusch wurde zum ersten Mal in den 1960er Jahren mit Hilfe eines Sonars der Oberon-Klasse entdeckt und bio-duck genannt, da es an eine schnatternde Ente erinnerte.[1] Die Quelle des Geräuschs blieb bis zum Jahr 2014 unbekannt.[2]

Der Südliche Zwergwal wurde bereits 1867 durch den deutschen Naturwissenschaftler Hermann Burmeister beschrieben. In den meisten Veröffentlichungen vor 1990 ging man jedoch von einer einzigen, weltweit lebenden Zwergwalart aus (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) und die südliche Population wurde als konspezifisch mit der nördlichen angesehen. Seit 2000 registrierte das Scientific Committee der International Whaling Commission (IWC) den Südlichen Zwergwal als eigenständige Art, die vom Nördlichen Zwergwal (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) und dessen die Südhalbkugel bewohnende noch kleinerer Zwergpopulation getrennt ist. Beide Zwergwalarten bilden wahrscheinlich die Schwestergruppe zu den übrigen Balaenoptera-Arten.[3]

Die Gesamtpopulation des Südlichen Zwergwals geht in die Hunderttausende. Die IUCN führt die Art in der Kategorie Near Threatened (potenziell gefährdet). Der Bestand in den Jahren 1986–1991 wird von der IWC auf 720.000 Tiere geschätzt, von 1993 bis 2002 auf 515.000 Tiere, allerdings überlappen sich die Konfidenzintervalle der Schätzungen. Die IWC konnte keine eindeutigen Gründe für den Rückgang der Population finden. Es gibt Hinweise, dass die Population vor dem Beginn des Walfangs größer war als die der letzten Jahre, aber auch Hinweise auf eine gleichbleibende oder größere Population.[4]

Der Südliche Zwergwal (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) ist eine Art der Furchenwale, die in den großen Weltmeeren auf der Südhemisphäre der Erde zwischen 20° und 65°S lebt.

The Antarctic minke whale or southern minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) is a species of minke whale within the suborder of baleen whales. It is the second smallest rorqual after the common minke whale and the third smallest baleen whale. Although first scientifically described in the mid-19th century, it was not recognized as a distinct species until the 1990s. Once ignored by the whaling industry due to its small size and low oil yield, the Antarctic minke was able to avoid the fate of other baleen whales and maintained a large population into the 21st century, numbering in the hundreds of thousands.[5] Surviving to become the most abundant baleen whale in the world, it is now one of the mainstays of the industry alongside its cosmopolitan counterpart the common minke. It is primarily restricted to the Southern Hemisphere (although vagrants have been reported in the North Atlantic) and feeds mainly on euphausiids.

In February 1867, a fisherman found an estimated 9.75 m (32.0 ft) male rorqual floating in the Río de la Plata near Belgrano, about ten miles from Buenos Aires, Argentina. After bringing it ashore he brought it to the attention of the German Argentine zoologist Hermann Burmeister, who described it as a new species, Balaenoptera bonaerensis, the same year.[6] The skeleton of another specimen, a 4.7 m (15 ft) individual taken off Otago Head, South Island, New Zealand, in October 1873, was sent by Professor Frederick Hutton, keeper of the Otago Museum in Dunedin, to the British Museum in London, where it was examined by the British zoologist John Edward Gray, who described it as a new species of "pike whale" (minke whale, B. acutorostrata) and named it B. huttoni.[7][8] Both descriptions were largely ignored for a century.

Gordon R. Williamson was the first to describe a dark-flippered form in the Southern Hemisphere, based on three specimens, a pregnant female taken in 1955 and two males taken in 1957, all brought aboard the British factory ship Balaena. All three had uniformly pale gray flippers and bicolored baleen, with white plates in the front and gray plates in the back.[9] Further studies in the 1960s supported his description.[10] In the 1970s osteological and morphological studies suggested it was at least a subspecies of the common minke whale, which was designated B. a. bonaerensis, after Burmeister's specimen.[11][12] In the 1980s further studies based on external appearance and osteology suggested there were in fact two forms in the Southern Hemisphere, a larger form with dark flippers and a "diminutive" or "dwarf form" with white flippers, the latter of which appeared to be more closely related to the common form of the Northern Hemisphere.[13][14] This was strengthened by genetic studies using allozyme and mitochondrial DNA analyses, which proposed there were at least two species of minke whale, B. acutorostrata and B. bonaerensis, with the dwarf form being more closely related to the former species.[15][16][17][18] One study, in fact, suggested that sei whales and the offshore form of Bryde's whale were more closely related to one another than either species of minke whale were to each other.[15] The American scientist Dale W. Rice supported these conclusions in his seminal work on marine mammal taxonomy, giving what he called the "Antarctic minke whale" (B. bonaerensis, Burmeister, 1867), full specific status[19] – this was followed by the International Whaling Commission a few years later. Other organizations followed suit.

Antarctic and common minke whales diverged from each other in the Southern Hemisphere 4.7 million years ago, during a prolonged period of global warming in the early Pliocene which disrupted the Antarctic Circumpolar Current and created local pockets of upwelling, facilitating speciation by fragmenting populations.[20]

There have been two confirmed hybrids between Antarctic and common minke whales. Both were caught in the northeastern North Atlantic by Norwegian whaling vessels. The first, an 8.25 m (27.1 ft) female taken off western Spitsbergen () on 20 June 2007, was the result of a pairing between a female Antarctic minke and a male common minke. The second, a pregnant female taken off northwestern Spitsbergen () on 1 July 2010, on the other hand, had a common minke mother and an Antarctic minke father. Her female fetus, in turn, was fathered by a North Atlantic common minke, demonstrating that back-crossing is possible between hybrids of the two species.[21][22]

The Antarctic minke is among the smallest of the baleen whales, with only the common minke and the pygmy right whale being smaller. The longest caught off Brazil were an 11.9 metres (39.0 feet) female taken in 1969 and an 11.27 metres (37.0 feet) male taken in 1975, the former four feet longer than the second longest females and the latter five feet longer than the second longest males.[23] Off South Africa, the longest measured were a 10.66 metres (35.0 feet) female and a 9.75 metres (32.0 feet) male.[24] The heaviest caught in the Antarctic were a 9 metres (29.5 feet) female that weighed 10.4 metric tons (11.5 short tons)[25] and an 8.4 metres (27.6 feet) male that weighed 8.8 metric tons (9.7 short tons).[26] At physical maturity, females average 8.9 metres (29.2 feet) and males 8.6 metres (28.2 feet). At sexual maturity, females average 7.59 metres (24.9 feet) and males 8.11 metres (26.6 feet). Calves are estimated to be 2.74 metres (9 feet) at birth.[24]

Like their close relative the common minke, the Antarctic minke whale is robust for its genus. They have a narrow, pointed, triangular rostrum with a low splashguard. Their prominent, upright, falcate dorsal fin – often more curved and pointed than in common minkes –is set about two-thirds the way along the back. About half of individuals have a light gray flare or patch on the posterior half of the dorsal fin, similar to that seen in species of dolphins in the genus Lagenorhynchus. They are dark gray dorsally and clean white ventrally. The lower jaw projects beyond the upper jaw and is dark gray on both sides.[27] Antarctic minkes lack the light gray rostral saddle present in the common and dwarf forms.[28] All individuals possess pale, thin blowhole streaks trailing from the blowhole slits, which first veer left and then right – particularly the right streak. These streaks appear to be more prominent and consistent on this species than on either the common or dwarf minke. Most also have a variably colored – light gray, light gray with dark edges, or simply dark – ear streak trailing behind the opening for the auditory meatus, which widens and becomes more diffuse posteriorly. A light gray variably shaped double chevron or W-shaped pattern (analogous to a similar pattern seen on their larger cousin the fin whale)[28] lies between the flippers. This broadens to form a light gray shoulder patch above the flippers. Like common and dwarf minkes, they have two light gray to whitish swaths, called the thorax and flank patches, the former running diagonally up from the axilla and diagonally down again to form a triangular intrusion into the dark gray of the thorax and the latter rising more vertically along its anterior edge and extending further dorsally before gradually sloping posteriorly to merge with the white of the ventral side of the caudal peduncle. A dark gray, roughly triangular thorax field separates the two, while a narrower dark gray shoulder infill separates the thorax patch from the shoulder patch. Two light gray, forward directed caudal chevrons extend from the dark gray field above, forming a whitish peduncle blaze between them. The smooth sided flukes, usually about 2.6 to 2.73 m (8.5 to 9.0 ft) wide, are dark gray dorsally and clean white (occasionally light gray to gray) ventrally with a thin, dusky margin. Some small, dark gray speckling may be present on the body.[13][29]

Antarctic minkes lack the bright white, transverse flipper band of the common minke and the white shoulder blaze and bright white flipper patch (occupying the proximal two-thirds of the flipper) of the dwarf minke. Instead, their narrow, pointed flippers, about one-sixth to one-eighth of the total body length, are normally either a plain light gray with an almost white leading edge and a darker gray trailing edge or two-toned, with a thin light gray or dark band separating the darker gray of the proximal third of the flipper from the lighter gray of the distal two-thirds. Unlike the dwarf minke, the dark gray between the eye and flipper does not extend unto the ventral grooves of the throat to form a dark throat patch; there is instead an irregularly shaped line running from about the level of the eye to the anterior insertion of the flipper, merging with the light gray of the shoulder patch.[13][14][28][29][30]

The longest baleen plates average 25 to 27 cm (9.8 to 10.6 in) in length and about 12.5 to 13.5 cm (4.9 to 5.3 in) in breadth and number 155 to 415 pairs (average 273). They are two-toned, with a dark gray outer margin on the posterior plates and a white outer margin on the anterior plates – though there may be some rows of dark plates amongst the white plates.[29] There is a degree of asymmetry, with a smaller number of white plates on the left side than on the right (12% on average for the left versus 34% on average for the right). The dark gray border occupies about one third of the width of the plates (ranging from about one-seventh to over half of its width), with the average width being greater on the left side than on the right. In contrast, dwarf minkes have smaller baleen plates of only 20 cm (7.9 in) in length, have a greater number of white plates (over 54%, often 100%) that lack this asymmetrical coloration, and have a narrow dark gray border (when present) of less than 6% of the width of the plate. Antarctic minkes have an average of 42 to 44 thin, narrow ventral grooves (range 32 to 70) that extend to about 48% of the length of the body – well short of the umbilicus.[13][31]

Antarctic minke whales occur throughout much of the Southern Hemisphere. In the western South Atlantic, they have been recorded off Brazil from 0°53'N to 27°35'S (nearly year-round),[32][33][34] Uruguay,[32] off central Patagonia in Argentina (November–December),[35] and in the Strait of Magellan and Beagle Channel of southern Chile (February–March),[36] while in the eastern South Atlantic they have been recorded in the Gulf of Guinea off Togo,[37] off Angola,[38] Namibia (February),[39][40] and Cape Province, South Africa.[24] In the Indian and Pacific Oceans, they have been recorded off Natal Province, South Africa,[24] Réunion (July),[41] Australia (July–August),[14] New Zealand, New Caledonia (June),[42] Ecuador (2°S, October),[43] Peru (12°30'S, September–October),[44] and the northern fjords of southern Chile.[45] Vagrants have been reported in Suriname – an 8.2 metres (26.9 feet) female was killed 45 km (28 mi) upstream the Coppename River in October 1963;[46] the Gulf of Mexico, where a 7.7 metres (25.3 feet) female was found dead off the US state of Louisiana in February 2013;[47] and off Jan Mayen (June) in the northeastern North Atlantic.[21]

They appear to disperse into offshore waters during the breeding season. In the spring (October–December), Japanese sighting surveys from 1976 to 1987 recorded relatively high encounter rates of minke whales off South Africa and Mozambique (20° – 30°S, 30° – 40°E), off Western Australia (20° – 30°S, 110° – 120°E), around the Gambier Islands of French Polynesia (20° – 30°S, 130° – 140°W), and in the eastern South Pacific (10° – 20°S, 110° – 120°W).[48] Later surveys, which distinguished between Antarctic and dwarf minke whales, showed that most of these were Antarctic minke whales.[3]

They have a circumpolar distribution in the Southern Ocean (where they have been recorded year-round),[49] including the Bellingshausen, Scotia,[50] Weddell and Ross Seas.[51] They are most abundant in the MacKenzie Bay-Prydz Bay area (60° – 80°E, south of 66°S) and relatively numerous off Queen Maud Land (0° – 20°E, 66° – 70°S), in the Davis (80° – 100°E, south of 66°S) and Ross Seas (160°E – 140°W, south of 70°S), and in the southern Weddell Sea (20° – 40°W, south of 70°S).[52] Like their larger cousin the blue whale, they have a particular affinity for the pack ice. In the spring (October–November), they occur widely throughout the pack ice zone to near the edge of the fast ice, where they have been observed between belts of pack ice and in leads and polynyas – often in heavy ice cover.[53] Some individuals have become trapped in the ice and were forced to overwinter in the Antarctic – for example, up to 120 "lesser rorquals" were trapped in a small breathing hole with sixty killer whales and an Arnoux's beaked whale in Prince Gustav Channel, east of the Antarctic Peninsula and west of James Ross Island, in August 1955.[54]

Two Antarctic minke whales marked with "Discovery tags" – 26 cm (10 in) stainless steel tubes with an inscription and number engraved on them – in the Southern Ocean during the austral summer (January) were recovered a few years later off northeastern Brazil (6° – 7°S, 34°W) during the austral winter (July and September, respectively). The first was marked off Queen Maud Land () and the second southeast of the South Orkney Islands (). Over twenty individuals marked with these Discovery tags showed large-scale movements around the Antarctic continent, each moving more than 30 degrees of longitude – two, in fact, had moved over 100 degrees of longitude. The first was marked off the Adélie Coast () and recovered the following season off the Princess Ragnhild Coast (), a minimum of 114 degrees of longitude. The second was marked north of Cape Adare () and recovered nearly six years later northwest of the Riiser-Larsen Peninsula (), a minimum of over 139 degrees of longitude. Both were marked and recovered in January.[55]

On 20 January 1972, a 49.5 cm (19.5 in) broken-off bill of a marlin (Makaira sp.) was found embedded in the rostrum of a minke whale caught in the Southern Ocean at , providing indirect evidence of migration to the warmer tropical or subtropical waters of the Indian Ocean.[56]

Earlier estimates suggested that there were several hundred thousand minke whales in the Southern Ocean.[5][57] In 2012, the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission agreed upon a best estimate of 515,000. The Report of the Scientific Committee acknowledged that this estimate is subject to some degree of negative bias because some minke whales would have been outside the surveyable ice edge boundaries.[58]

Antarctic minke whales become sexually mature at 5 to 8 years of age for males and 7 to 9 years of age for females. Both become physically mature at about 18 years of age. After a gestation period of about 10 months, a single calf of 2.73 m (9.0 ft) is born – twin and triplet fetuses have been reported, but are rare. After a lactation period of about six months, the calf is weaned at a length of 4.6 m (15 ft). The calving interval is estimated to be about 12.5 to 14 months. Peak calving is from May to June, while peak conception is from August to September. Females may live up to 43 years of age.[24][59][60]

Antarctic minke whales feed almost exclusively on euphausiids. In the Southern Ocean, over 90% of individuals fed on Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba); E. crystallorophias also formed an important part of the diet in some areas, particularly in the relatively shallow waters of Prydz Bay. Rare and incidental items include calanoid copepods, the pelagic amphipod Themisto gaudichaudii, Antarctic sidestripes (Pleuragramma antarcticum), the crocodile icefish Cryodraco antarcticus, nototheniids, and myctophids.[61][62][63] The majority of individuals examined off South Africa had empty stomachs. The few that did have food in their stomachs had all preyed on euphausiids, mainly Thysanoessa gregaria and E. recurva.[24]

Antarctic minke whales are the main prey item of Type A killer whales in the Southern Ocean.[64] Their remains have been found in the stomachs of killer whales caught by the Soviets,[65] while individuals caught by the Japanese exhibited damaged flippers with tooth rake scars and parallel scarring on the body suggestive of killer whale attacks.[24] Large groups of killer whales have also been observed chasing, attacking, and even killing Antarctic minke whales.[51][64][66][67] Most attacks involve Type A killer whales, but on one occasion, in January 2009, a group of ten Type B or pack ice killer whales, which normally preyed on Weddell seals in the area by wave-washing them off ice floes, were observed to attack, kill, and feed on a juvenile Antarctic minke whale in Laubeuf Fjord, between Adelaide Island and the Antarctic Peninsula.[68]

Little has been published on the parasitic and epibiotic fauna of Antarctic minke whales. Individuals were often found with orange-brown to yellowish patches of the diatom Cocconeis ceticola on their bodies – 35.7% off South Africa and 67.5% in the Antarctic. Of a sample of whales caught by a Japanese expedition along the ice edge, one-fifth was infested with cyamids (those from one whale were identified as Cyamus balaenopterae). Several hundred of these whale lice can be found on a single whale, with an average of 55 per individual – most are found at the end of the ventral grooves and around the umbilicus. The copepod Pennella was found on only one whale. Cestodes were commonly found in the intestines (one example was identified as Tetrabothrius affinis).[24]

Antarctic minke whales are more gregarious than their smaller counterparts, the common and dwarf minke whale. The average group size in the Antarctic was about 2.4 (adjusted downwards for observer bias), with about a quarter of the sightings consisting of singles and one-fifth of pairs; the largest aggregation consisted of 60 individuals.[69] Off South Africa, the average group size was about two, with singles (nearly 46%) and pairs (31%) being the most common – the largest was 15.[24] Off Brazil, most sightings were of singles (32.6%) or pairs (31.5%), with the largest group consisting of 17 individuals.[23]

Like common minke whales, Antarctic minkes exhibit a great deal of spatial and temporal segregation by sex, age class, and reproductive condition. Off South Africa, immature animals predominate from April to May, while mature whales (mainly males) dominate from June onwards – in August and September mature males often accompany cow-calf pairs.[24] Off Brazil, a good proportion of the individuals are immature (particularly for females) in July and August, but by September most are mature, and by October and November nearly all are mature.[31] Females outnumber males two to one off Brazil, while the opposite is true off South Africa, where males outnumber females nearly two to one. Over a quarter of the females off South Africa were found to be lactating, whereas lactating females are very rare in the Antarctic – though a cow-calf pair was observed in the austral winter (August) in the Lazarev Sea.[49] In the sub-Antarctic and Antarctic, immature animals are normally solitary and occur in lower latitudes further offshore, while mature whales are typically found in mixed groups (usually one sex outnumbers the other, and groups composed solely of males or females are occasionally found) and occur in higher latitudes. Mature males dominate in middle latitudes, while mature females predominate in the higher latitudes of the pack ice zone – from two-thirds to three-quarters of the whales in the Ross Sea consist of pregnant females.[25][70][71][72][73][74][75][76]

An immature Antarctic minke whale was observed briefly associating with four dwarf minke whales on the Great Barrier Reef in July 2000.[28]

Unlike common minke whales, they often have a prominent blow, which is particularly visible in the calmer waters near the pack ice.[69] In the narrow holes and cracks in the pack ice they have been observed spyhopping – raising their head vertically – to expose their blowholes to breathe; individuals have even been seen to break breathing holes through sea ice in the winter (July–August), rising in a similar manner.[49][51][53] When traveling fast in open water they can create larger versions of the "roostertail" of spray created by their smaller cousin, the Dall's porpoise.[27] During bouts of feeding they will lunge multiple times onto their side (either left or right) into a dense patch of prey with mouth agape and ventral pleats expanded as their gular pouch fills with prey-laden water. After making a series of shorter dives during which they will surface anywhere from two to fifteen times, they will make a longer dive of up fourteen minutes.[51] Shallower dives of normally less than 40 m (130 ft) are made at night (from about 8 p.m. to about 2 am) while deeper dives that can be over 100 m (330 ft) deep are made during the day (from about 2 a.m. to about 8 pm).[77]

Antarctic minke whales produce a variety of sounds, including whistles, calls reminiscent of a clanging bell, clicks, screeches, grunts, downsweeps,[51] and a sound called bio-duck.[77] Downsweeps are intense, low frequency calls that sweep down from about 130 to 115 Hz to about 60 Hz,[78] with a peak frequency of 83 Hz. Each sweep has a duration of 0.2 seconds and an average source level of about 147 decibels at a reference pressure of one micropascal at one metre. The bio-duck call, first described in the 1960s and named by sonar operators on Oberon-class submarines for its purported resemblance to the quack of a duck, consist of a series of anywhere from three to a dozen pulse trains that range from 50 to 200 Hz and have a peak frequency of about 154 Hz – they sometimes also possess harmonics of up to 1 kHz. They are repeated about every 1.5 to 3 seconds and have a source level of 140 decibels at a reference pressure of one micropascal at one metre. Their source remained a mystery for decades until attributed to the Antarctic minke whale in a paper published in 2014 – though it had been suggested to originate from this species as early as the mid-2000s.[79] It has been recorded in the Ross and Lazarev Seas, over Perth Canyon, off Western Australia from late June to early December,[80] and in the King Haakon VII Sea from April to December.[81] The sound seems to be made near the surface before foraging dives, but nothing is known of its function.[77][82]

The barque Antarctic, sent by whaling pioneer Svend Foyn and led by Henrik Johan Bull, managed to harpoon at least three minke whales in the Antarctic between December 1894 and January 1895. Two were saved, both being used for fresh meat (one had only yielded two barrels of blubber).[83] In December 1923, when the men of the first modern whaling expedition to visit the Ross Sea saw "a number of spouts" after leaving the ice edge they were soon disgusted to find out that they from lowly minke whales.[84] The few caught by the British in the 1950s were taken more for curiosity than anything else. The chemist Christopher Ash, who had served on the British factory ship Balaena during this time, stated that they were small enough to be lifted by their tails using a 10-ton spring balance and weighed entire. "Generally this is done when there are no other whales about and the deck empty except for a crowd of sightseers," Ash explained, "but this crowd quickly scatters when the whale is just hanging free and starts to spin around and swing from side to side, as it almost always does." Like Bull before him, Ash commented on their meat, which he described as "fine-textured in comparison with the other whales, and if properly cooked almost indistinguishable from beef."[85]

They were primarily exploited for this very reason – their high quality meat – in later years, which fetched as much as two dollars a pound in 1977.[86] With the larger blue, fin, and sei whales depleted, whaling nations focused their attention on the smaller, but more numerous, minke whales. Though the Soviets had caught several hundred in the 1950s, it was not until 1971–72 that a significant catch was made, with over 3,000 being taken (nearly all by a single Japanese expedition).[87] Not wanting to repeat the same mistakes it had made with previous species, the International Whaling Commission set a quota of 5,000 for the following season, 1972–73. Despite these precautions, the quota was exceeded by 745 – later quotas would be as high as 8,000.[88]

During the commercial whaling era, from 1950 to 1951 to 1986–87, 97,866 minke whales (the vast majority probably Antarctic minkes) were caught in the Southern Ocean – mainly by the Japanese and Soviets – with a peak of 7,900 being reached in 1976–77.[89] Harpoon guns of lesser caliber and "cold harpoons" (harpoons without explosive shells) had to be used due to their small size, while no air was pumped into the carcasses when they were tied alongside for towing to ensure the greatest quality of meat.[86][90] While an expedition or two was fitted out each year specifically for minke whales – the Jinyo Maru in 1971–72, the Chiyo Maru from 1972 to 1973 to 1974–75, and the Kyokusei Maru in 1973–74 – most expeditions, which targeted other species, ignored minkes during the peak of the whaling season (November–December and late February to early March) and only caught them on whaling grounds relatively close to those of larger ones – the minke whaling grounds were much further south (south of 60°S) than those for fin and sei whales.[87][91][92]

From 1987 to the present, Japan has been sending a fleet consisting of a single factory ship and several catcher/spotting vessels to the Southern Ocean to catch Antarctic minkes under Article VIII of the IWC, which allows the culling of whales for scientific research. The first research program, Japanese Research Program in the Antarctic (JARPA), began in 1987–88, when 273 Antarctic minkes were caught. The quota and catch soon increased to 330 and 440. In 2005–06, the second research program, JARPA II, began. In its first two years, in what Japan called its "feasibility study", 850 Antarctic minkes, as well as 10 fin whales, were to be taken each season (2005–06 and 2006–07). The quota was reached in the first season, but due to a fire, only 508 Antarctic minkes were caught in the second. In 2007–08, because of constant harassment from environmental groups, they failed to reach the quota again, with a catch of only 551 whales.

Beginning in 1968, larger numbers of minke whales were caught off Natal, South Africa, mainly to supplement the dwindling supply of larger species, particularly the sei whale. A total of 1,113 whales (nearly all Antarctic minke, but a few dwarf minke as well) were caught off the province between 1968 and 1975, with a peak of 199 in 1971. They were taken by whale catchers of 539 to 593 gross tons with 90 mm harpoon guns mounted on their bows, which brought them to the whaling station at Durban () for processing. Gunners refused to take minkes early in the day, because sharks devoured any minke carcasses that were flagged, forcing the catchers to tow them during the chasing of other whales and thus slowing them down. They also could not use asdic, as it frightened them and lead to protracted chases. The season lasted from February to September, with a peak in the last month of the season.[24][93]

In 1966, minke whales became the target of whaling operations off northeastern Brazil (6° – 8°S) due, once again, to the decline of sei whales. Over 14,000 were caught between 1949 and 1985, with a peak of 1,039 in 1975. They were caught by a succession of whale catchers – the 367-ton Koyo Maru 2 (1966–1971), the 306-ton Seiho Maru 2 (1971–1977), and the 395-ton Cabo Branco (also called Katsu Maru 10, 1977–1985) – up to 100 miles offshore and brought to the whaling station at Costinha, operated by the Compania de Pesca Norte do Brasil (COPESBRA) since 1911. The season lasted from June to December, with a peak in either September or October.[31][94][95]

An 8.2 m (27 ft) male Antarctic minke whale (confirmed by genetics) was caught west of Jan Mayen () in the northeastern North Atlantic on 30 June 1996.[21]

Entanglement in fishing gear and probably ship strikes are other sources of mortality. The former have been reported off Peru and Brazil, and the latter off South Australia. All involved calves or juveniles.[32][44][96]

The Antarctic minke whale is currently considered Near Threatened by the IUCN red list. However, the IUCN states that the population size is "clearly in the hundreds of thousands".[3]

The Antarctic minke whale is listed on Appendix II[97] of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). It is listed on Appendix II[97] as it has an unfavourable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organised by tailored agreements.

In addition, the Antarctic minke whale is covered by the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region.[98]

The Antarctic minke whale or southern minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) is a species of minke whale within the suborder of baleen whales. It is the second smallest rorqual after the common minke whale and the third smallest baleen whale. Although first scientifically described in the mid-19th century, it was not recognized as a distinct species until the 1990s. Once ignored by the whaling industry due to its small size and low oil yield, the Antarctic minke was able to avoid the fate of other baleen whales and maintained a large population into the 21st century, numbering in the hundreds of thousands. Surviving to become the most abundant baleen whale in the world, it is now one of the mainstays of the industry alongside its cosmopolitan counterpart the common minke. It is primarily restricted to the Southern Hemisphere (although vagrants have been reported in the North Atlantic) and feeds mainly on euphausiids.

El rorcual austral o Minke antártico (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) es una especie de cetáceo misticeto de la familia Balaenopteridae.

La traducción del latín de Balaenoptera bonaerenses sería “ballena alada bonaerense”. En cuanto a su nombre común, recibe el nombre de rorcual austral debido a que es común verle en los meses de verano en aguas de la Antártida. Otro nombre por el que se le conoce, Minke antártico, se debe a una curiosa historia. Según esta, en un barco ballenero noruego, capitaneado por Svend Foyn, un marinero apellidado Meincke dio la voz de alarma al avistar a lo lejos un rorcual azul, sin embargo, grande fue la sorpresa del resto de la tripulación al ver que se trataba de estas pequeñas especies que rondan los 7 metros de longitud. A causa de esto, y como forma broma, los balleneros comenzaron a llamar a estos pequeños animales "rorcuales de Meincke", que al pasar el tiempo se trasformó en rorcuales Minke.[2][3][4]

El rorcual austral junto con el rorcual aliblanco son las especies más pequeñas de rorcuales (la ballena franca pigmea es el cetáceo misticeto más pequeño que existe). Su longitud varía de 7,2 a 11 metros y su peso oscila entre 5,8 y 9,1 toneladas. En promedio, las hembras son aproximadamente 1 metro más largas que los machos. Su dorso es gris oscuro y el vientre blanco.

El rorcual austral habita en todos los océanos del hemisferio sur. Durante el verano se encuentra cerca de la Antártida, pero se mueve más hacia el norte en invierno, superponiendo su rango de distribución con el rorcual aliblanco (la otra variedad de rorcual Minke).

Los datos sobre el estado de conservación del rorcual antártico se consideran insuficientes en la lista roja de UICN, por ser “incapaces de proporcionar estimaciones confíables y actualizadas”.[1]

El rorcual austral o Minke antártico (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) es una especie de cetáceo misticeto de la familia Balaenopteridae.

Balaenoptera bonaerensis Balaenoptera generoko animalia da. Artiodaktiloen barruko Balaenopteridae familian sailkatuta dago.

Balaenoptera bonaerensis Balaenoptera generoko animalia da. Artiodaktiloen barruko Balaenopteridae familian sailkatuta dago.

Balaenoptera bonaerensis

Le petit rorqual de l'Antarctique ou Baleine de Minke[2] (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) est une baleine étroitement apparentée à B. acutorostrata et qui se rencontre dans les mers et océans de l'hémisphère Sud. Cette espèce a été scientifiquement décrite en 1867[1]. C'est une espèce qui a été abondamment chassée par la pêche baleinière japonaise, qui a dû en échange de dérogation au moratoire sur la chasse aux cétacés (« permis spécial ») proposer des méthodes plus "humaines" de mise à mort[3] et fournir des données scientifiques sur l'espèce, dont sur leur santé[4] et sur les teneurs de la chair et de certains organes en métaux lourds[5] ou organochlorés[6].

Balaenoptera bonaerensis mesure de 7,2 à 10,7 m pour un poids de 5,8 à 9,1 t. En moyenne les femelles mesurent un mètre de plus que les mâles. Cette espèce se nourrit principalement de krill[7]. Les nouveau-nés mesurent de 2,4 à 2,8 m et pèsent environ 400 kg. Son dos est gris foncé et son ventre est blanc.

Il peut émettre un son qui ressemble à celui du canard[8].

Ce chant répétitif, régulièrement entendu par les hydrophones placés dans les eaux froides de l'océan Austral était connu des océanographes depuis les années 1960. Mais ce n'est qu'en 2013 qu'on l'a identifié comme émis par Balaenoptera bonaerensis. Il avait d'abord été attribué à des sous-marins, mais ils n'étaient émis qu'au printemps et en hiver, ce qui a fait évoqué un phénomène naturel saisonnier. Des microphones posés sur deux rorquals B. bonaerensis ont pu enregistrer 32 de ces appels qui semblent généralement émis près de la surface et fréquemment juste avant une plongée de l'animal.

L'épaisseur de la couche de lard de mammifère marin de cette espèce, mesurée dans plusieurs secteurs de l'océan austral dans le cadre des pêches dites "scientifiques" du Japon semble en diminution[9], ce qui pourrait indiquer un mauvais état de santé ou une difficulté à s'alimenter (manque de krill par exemple), cette couche grasse étant considéré comme un indicateur de bonne santé chez les baleines[10].

Balaenoptera bonaerensis

Le petit rorqual de l'Antarctique ou Baleine de Minke (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) est une baleine étroitement apparentée à B. acutorostrata et qui se rencontre dans les mers et océans de l'hémisphère Sud. Cette espèce a été scientifiquement décrite en 1867. C'est une espèce qui a été abondamment chassée par la pêche baleinière japonaise, qui a dû en échange de dérogation au moratoire sur la chasse aux cétacés (« permis spécial ») proposer des méthodes plus "humaines" de mise à mort et fournir des données scientifiques sur l'espèce, dont sur leur santé et sur les teneurs de la chair et de certains organes en métaux lourds ou organochlorés.

O rorcual austral, Balaenoptera bonaerensis, é un unha especie de mamífero mariño da orde dos cetáceos, suborde dos misticetos e familia dos balenoptéridos, unha das sete que integran o xénero Balaenoptera.

É un cetáceo de pequeno tamaño estreitamente emparentado coa especie Balaenoptera acutorostrata que habita nas augas do hemisferio austral, de aí o seu nome vulgar.

A especie foi descrita por primeira vez en 1867 polo naturalista, paleontólogo e zoólogo alemán, nacionalizado arxentino, Hermann Burmeister, en Actas Soc. Paleo., Buenos Aires: XXIV.[2]

Ademais de polo nome que lle deu Burmeister, e actualmente válido, a especie coñeceuse tamén polos sinónimos:[3]

O nome específico, bonaerensis, significa 'bonaerense', é dicir, 'de Buenos Aires'. Porén, o epíteto vulgar co que se coñece, austral, é debido a que é común velo nos meses de verán en augas da Antártida. Ademais, dise así por oposición ao seu próximo parente (durante moitos anos pensouse que eran conespecíficos), o Balaenoptera acutorostrata, que se distribúe polo hemisferio boreal.

O rorcual austral, xunto co Balaenoptera acutorostrata son sas especies máis pequenas de rorcuais (a balea anana é o cetáceo misticeto máis pequeno que existe).

A súa lonxitud varía de 7,2 a 11 m, e o seu peso oscila entre 5,8 e 9,1 t. En promedio, as femias son aproximadamente 1 m máis longas que os machos.

A coloración do seu dorso é gris escura, e o ventre, branco.

O rorcual austral habita en todos os océanos do hemisferio sur. Durante o verán se encontra cerca da Antártida, pero se move máis cata ao norte en inverno, superponendo parcialmente así a súa área de distribución coa do Balaenoptera acutorostrata.

É unha especie que foi cazada extensivamente pola frota baleeira xaponesa, que tiña, a cambio da derrogación da moratoria sobre a caza de baleas (un "permiso especial") a cambio de ofrecer métodos más 'humanos' para a morte deste animal, e de subministrar información científica sobre a especie, especialmente sonre a súa saúde e o contido na súa carne e en certos órganos de metais pesados e compostos organoclorados.[4][5][6][7]

Os datos sobre o estado de conservación do rorcual antártico considéranse insuficientes na lista vermella da UICN, por seren «incapaces de proporcionar estimacións confiábeis e actualizada».[1]

O rorcual austral, Balaenoptera bonaerensis, é un unha especie de mamífero mariño da orde dos cetáceos, suborde dos misticetos e familia dos balenoptéridos, unha das sete que integran o xénero Balaenoptera.

É un cetáceo de pequeno tamaño estreitamente emparentado coa especie Balaenoptera acutorostrata que habita nas augas do hemisferio austral, de aí o seu nome vulgar.

La balenottera minore antartica (Balaenoptera bonaerensis Burmeister, 1867), o balenottera minore australe, è una delle specie più comuni della famiglia dei Balenotteridi[2].

Secondo studi recenti il misterioso suono ritmico rilevato da anni nei mari attorno all'Antartide sarebbe riconducibile proprio a questa specie.

La balenottera minore antartica è uno dei rappresentanti più piccoli della famiglia dei Balenotteridi, nonché uno dei Misticeti di minori dimensioni. Tra i Balenotteridi solamente la balenottera minore comune è più piccola, e tra i Misticeti la caperea ha dimensioni ancora inferiori. La sua lunghezza varia tra i 7,2 e i 10,7 metri e il peso tra le 5,8 e le 9,1 tonnellate[3]. In media le femmine sono circa un metro più lunghe dei maschi[3]. Alla nascita misurano tra i 2,4 e i 2,8 metri[3].

Il dorso è di colore grigio scuro e il ventre è bianco. Su entrambi i fianchi è presente una striscia di colore grigio più chiaro estesa dal dorso al ventre. Le natatoie sono di colore scuro, con il margine anteriore bianco[3].

La balenottera minore antartica si differenzia da quella comune sotto vari aspetti. Ha dimensioni leggermente maggiori e, a differenza dell'altra, non ha la banda bianca sulle natatoie. Presenta inoltre differenze meno evidenti nella colorazione e nella forma del corpo[3].

La balenottera minore antartica viene avvistata generalmente da sola o in coppie, ma nelle zone di alimentazione sono state registrate anche aggregazioni di centinaia di esemplari. La sua dieta consiste soprattutto di krill, e a sua volta viene predata dalle orche (Orcinus orca)[4].

La balenottera minore antartica raggiunge la maturità sessuale a 7-8 anni, e vive in media circa 50 anni. L'accoppiamento avviene in inverno. Dopo una gestazione di dieci mesi, la femmina partorisce generalmente un unico piccolo, sebbene talvolta avvengano anche parti gemellari o addirittura trigemini. Il piccolo viene svezzato a cinque mesi di età, e rimane con la madre fino a due anni[4].

La balenottera minore antartica può nuotare anche a velocità di 20 km orari e immergersi per 20 minuti, nonostante le sue immersioni durino in media solo pochi minuti. È una specie piuttosto curiosa, nota per avvicinarsi frequentemente alle imbarcazioni[4].

Diffusa in tutti gli oceani dell'emisfero australe, la balenottera minore antartica può talvolta oltrepassare l'Equatore ed essere avvistata nell'emisfero boreale. In estate, si raduna in gruppi numerosi nelle acque antartiche per alimentarsi, mentre in inverno si sposta verso nord per riprodursi in acque tropicali o temperate. Tuttavia, non tutte le balenottere migrano: alcune trascorrono tutto l'anno in Antartide[4].

È presente sia in acque costiere che in aperto oceano. Durante l'estate, si raduna ai margini della banchisa o tra il pack e il polynya[4].

La prima cattura di quella che probabilmente era una balenottera minore antartica (il rapporto stilato non indica se si trattava di una caperea o di questa specie, ma era quasi sicuramente quest'ultima) venne effettuata da balenieri britannici durante la stagione di caccia in Antartide del 1950-51. Nel 1957-58, il numero di esemplari catturati era salito a 493 capi. Le catture furono relativamente poche e poco più che sporadiche nelle stagioni seguenti, fino al 1967-68, quando ne vennero catturate 605. Nel 1971-72 ne vennero prese 3021. Non volendo incappare negli stessi errori fatti in precedenza con altre specie, la International Whaling Commission (IWC) stabilì una quota di 5000 esemplari per la stagione successiva, 1972-73. Nonostante queste precauzioni, ne vennero catturati 745 esemplari in più[5].

La quota stabilita per il 1973-74 fu ancora di 5000 capi, ma Giappone e Unione Sovietica, le uniche due nazioni che allora potevano cacciare balene in acque antartiche, protestarono, e la quota fu portata a 7713 capi (tutti catturati). Da allora le catture annue fluttuarono tra i 5000 e i 7000 capi (con un massimo di 7900 nel 1976-77) fino al 1986-87, quando nei mari antartici ebbe fine lo sfruttamento commerciale di questa specie[5].

Dal 1987 a oggi, il Giappone ha inviato ogni anno nell'oceano Australe una flotta composta da un'unica nave officina e da alcune baleniere all'apposito scopo di catturare balenottere minori antartiche, come stabilito nell'Articolo VIII della IWC, che consente la cattura di balene per ricerche scientifiche. Il primo programma di ricerca, il Japanese Research Program in the Antarctic (JARPA), ebbe inizio nel 1987-88, con la cattura di 273 esemplari. Le quote e le catture vennero ben presto portate da 330 a 440. Nel 2005-06, ebbe inizio il secondo programma di ricerca, il JARPA II. Durante i primi due anni (2005-06 e 2006-07), in quelli che il Giappone chiamò «studi di attuabilità», vennero stabilite quote per la cattura di 850 balenottere minori antartiche e 10 balenottere comuni. La quota venne raggiunta nella prima stagione, ma, a causa di un incendio, nella seconda vennero catturati solo 508 individui. Nel 2007-08, a causa dell'ostilità dei gruppi ambientalisti, la quota non venne nuovamente raggiunta, e vennero catturate solo 551 balenottere[5].

Nel 2012 il comitato scientifico della International Whaling Commission ha stimato il numero totale di esemplari in 515.000 unità[6].

La balenottera minore antartica (Balaenoptera bonaerensis Burmeister, 1867), o balenottera minore australe, è una delle specie più comuni della famiglia dei Balenotteridi.

Secondo studi recenti il misterioso suono ritmico rilevato da anni nei mari attorno all'Antartide sarebbe riconducibile proprio a questa specie.

De Antarctische dwergvinvis (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) is een walvis uit de familie der vinvissen (Balaenopteridae), die enkel op het zuidelijk halfrond voorkomt. De Antarctische dwergvinvis wordt vaak als een ondersoort van de dwergvinvis (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) gezien, maar onder andere door de Internationale Walvisvaartcommissie beschouwd als een aparte soort.

De Antarctische dwergvinvis is een van de kleinste soorten vinvissen. Hij wordt tussen de 10 en 11 meter lang en 9 à 10 ton zwaar. Vrouwtjes worden groter dan mannetjes. Bij de meeste Antarctische dwergvinvissen ontbreekt de bleke band, die bij de meeste gewone dwergvinvissen over de borstvinnen loopt. De schouder is licht- tot donkergrijs van kleur.

Hij voedt zich voornamelijk met krill, aangevuld met in scholen levende vissen. Jagen doen ze in open zee, maar eveneens onder oppervlakte-ijs.[2]

Op het zuidelijk halfrond leeft naast de Antarctische dwergvinvis nog een kleinere vorm dwergvinvis. Deze vorm is nauwer verwant aan de gewone dwergvinvis, die verder alleen op het noordelijk halfrond voorkomt, dan aan de Antarctische dwergvinvis en is mogelijk een ondersoort van de gewone dwergvinvis.

De Antarctische dwergvinvis komt waarschijnlijk op het gehele zuidelijk halfrond voor, en kan worden aangetroffen van de polaire tot de tropische wateren. Hij komt voornamelijk voor in kustwateren, onder andere in de wateren rond Antarctica en de Australische kust, maar wordt ook op open zee waargenomen. Rond Antarctica komt hij voor tot de rand van het pakijs. De Antarctische dwergvinvis is vooral 's zomers rond Antarctica te vinden, waar de voedselgronden liggen. 's Winters, in het voortplantingsseizoen, brengen ze verder noordwaarts door, tussen de 7° en 35° zuiderbreedte.

De Antarctische dwergvinvis is waarschijnlijk de meest algemene soort baleinwalvis. Hij is in het verleden ook zwaar bejaagd, voornamelijk rond de Antarctische wateren door Japan en Sovjet-Unie, en voor de kust van Brazilië, waar tussen 1965 en 1985 ongeveer 14.600 dieren werden gedood. Er wordt nog steeds door Japan op de soort gejaagd, onder het mom van wetenschappelijk onderzoek. Ze vangen jaarlijks zo'n driehonderd dieren.

Bronnen, noten en/of referentiesDe Antarctische dwergvinvis (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) is een walvis uit de familie der vinvissen (Balaenopteridae), die enkel op het zuidelijk halfrond voorkomt. De Antarctische dwergvinvis wordt vaak als een ondersoort van de dwergvinvis (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) gezien, maar onder andere door de Internationale Walvisvaartcommissie beschouwd als een aparte soort.

Sørlig vågehval (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) er en art i finnhvalslekten, en slekt som inkluderer åtte arter og tilhører finnhvalfamilien, som totalt inkluderer tre slekter og ni eller ti (det hersker en viss uenighet) bardehvaler.

Sørlig vågehval ble tidligere regnet som en underart av vågehval, men etter en avgjørelse i IWC i juni 2000 regnes disse nå som separate arter.[1]

Sørlig vågehval blir noe større enn den nordlige, og hunnene kan trolig bli nærmere 11 meter lange og veie opp mot 14 metriske tonn på det meste. Hunnene er generelt noe større enn hannene, som trolig ikke blir over 10 meter lange. Gjennomsnittsstørrelsen er imidlertid langt mindre for begge kjønn, trolig omkring 6-9 meter i lengde og 4-6 tonn i vekt. I sør finnes det også en dvergform at denne arten.

Sørlig vågehval er utbredt i en sirkulær omkrets på den sørlige halvkule, fra ekvator og sør mot Antarktis. Dvergformen har en mindre sirkulær utbredelse lenger mot sør. Det finnes ingen sikre estimater for totalbestanden av sørlig vågehval. IWC antydet tidlig på 1990-tallet at den kunne være på omkring 760 000 dyr, men dette har kommisjonen senere trukket tilbake. Det finnes derfor ingen sikre anslag for populasjonen av sørlig vågehval på den sørlige halvkule. Discovery Channel anslo i 2009 en bestand på 650 000.

Sørlig vågehval (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) er en art i finnhvalslekten, en slekt som inkluderer åtte arter og tilhører finnhvalfamilien, som totalt inkluderer tre slekter og ni eller ti (det hersker en viss uenighet) bardehvaler.

Sørlig vågehval ble tidligere regnet som en underart av vågehval, men etter en avgjørelse i IWC i juni 2000 regnes disse nå som separate arter.

Sørlig vågehval blir noe større enn den nordlige, og hunnene kan trolig bli nærmere 11 meter lange og veie opp mot 14 metriske tonn på det meste. Hunnene er generelt noe større enn hannene, som trolig ikke blir over 10 meter lange. Gjennomsnittsstørrelsen er imidlertid langt mindre for begge kjønn, trolig omkring 6-9 meter i lengde og 4-6 tonn i vekt. I sør finnes det også en dvergform at denne arten.

Sørlig vågehval er utbredt i en sirkulær omkrets på den sørlige halvkule, fra ekvator og sør mot Antarktis. Dvergformen har en mindre sirkulær utbredelse lenger mot sør. Det finnes ingen sikre estimater for totalbestanden av sørlig vågehval. IWC antydet tidlig på 1990-tallet at den kunne være på omkring 760 000 dyr, men dette har kommisjonen senere trukket tilbake. Det finnes derfor ingen sikre anslag for populasjonen av sørlig vågehval på den sørlige halvkule. Discovery Channel anslo i 2009 en bestand på 650 000.

Płetwal antarktyczny[3] (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) – gatunek ssaka z rodziny płetwalowatych (Balaenopteridae) występujący we wszystkich oceanach na południe od równika. Wcześniej uznawany za podgatunek płetwala karłowatego. Na podstawie badań mitochondrialnego DNA ustalono, że gatunki te prawdopodobnie oddzieliły się od siebie 5 milionów lat temu, w pliocenie.

Długość zwierzęcia wynosi od ok. 6 do ok. 10,2 m. Przeciętna masa ciała to ok. 7 ton, maksymalna 11 ton. Podobny do, nieco mniejszego od niego, płetwala karłowatego. Grzbiet ciemnoszary, brzuch jasny. Od płetwala karłowatego odróżnia go brak białej plamy na płetwach, a także nieco większa czaszka.

Mogą żyć samotnie, ale zazwyczaj tworzą grupy składające się z 2–4 osobników. Pływają dość szybko – osiągają prędkość 20 km/h. Zazwyczaj na powierzchnię wody wypływają co 2–6 minut, by zaczerpnąć 5-8 oddechów, mogą jednak przebywać pod wodą do 20 minut. Żywią się krylem, zwłaszcza krylem antarktycznym. W ich żołądkach znajdowano także kryle z gatunków Euphasia frigida i Thysanoessa macrura. Zwyczaje żywieniowe odróżniają je od żywiących się rybami płetwali karłowatych. Pożywiają się zazwyczaj wczesnym rankiem i późnym wieczorem.

Niewiele wiadomo o zwyczajach rozrodczych tych waleni. Rozmnażają się w lecie. Samica po 10-miesięcznej ciąży rodzi jedno młode, które karmi mlekiem przez 3–6 miesięcy. Samce nie biorą udziału w wychowaniu potomstwa. Młode opuszcza matkę w wieku 2 lat, dojrzałość płciową osiąga w wieku 7 lat. Najstarszy znany osobnik żył 73 lata.

Głównym naturalnym wrogiem tych zwierząt jest orka. Często poławiane są także przez japońskich wielorybników. Dane dotyczące liczebności gatunku nie są znane, jednak prawdopodobnie spadła ona znacznie pod koniec XX wieku.

Płetwal antarktyczny (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) – gatunek ssaka z rodziny płetwalowatych (Balaenopteridae) występujący we wszystkich oceanach na południe od równika. Wcześniej uznawany za podgatunek płetwala karłowatego. Na podstawie badań mitochondrialnego DNA ustalono, że gatunki te prawdopodobnie oddzieliły się od siebie 5 milionów lat temu, w pliocenie.

A baleia-minke-antártica ou baleia-minke-austral (nome científico: Balaenoptera bonaerensis) é uma espécie de cetáceo da família Balaenoptera. Está distribuída em todos os oceanos do Hemisfério Sul. Foi considerada coespecífica com a Balaenoptera acutorostrata, sendo tratada como uma subespécie, entretanto análises moleculares (DNA mitocondrial) demonstraram que ambas não são mais próximas do que qualquer outra espécie do gênero.[3]

A baleia-minke-antártica ou baleia-minke-austral (nome científico: Balaenoptera bonaerensis) é uma espécie de cetáceo da família Balaenoptera. Está distribuída em todos os oceanos do Hemisfério Sul. Foi considerada coespecífica com a Balaenoptera acutorostrata, sendo tratada como uma subespécie, entretanto análises moleculares (DNA mitocondrial) demonstraram que ambas não são mais próximas do que qualquer outra espécie do gênero.

Antarktisk vikval (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) är en art i familjen fenvalar som i sin tur tillhör underordningen bardvalar.

Tidigare betraktades vanlig vikval och antarktisk vikval som en enda art och vissa zoologer har fortfarande denna uppfattning. Nyare studier av individernas mitokondriellt DNA förespråkar en uppdelning i två arter. Undersökningar bekräftade dessutom att antarktisk vikval är vikvalens närmaste släkting och att de tillsammans bildar en klad.[2]

Antarktisk vikval förekommer i alla havsområden söder om ekvatorn. Under sommaren vistas individerna nära Antarktis men under vintern förekommer de längre norrut och utbredningsområdet överlappar delvis med dvärgformen av den vanliga vikvalen.[1]

Antarktisk vikval är en av de minsta fenvalarna och även en av de minsta bardvalar. Bland fenvalarna är endast den vanliga vikvalen mindre och bland bardvalar är dessutom dvärgrätvalen mindre. Antarktisk vikval når en längd mellan 7,2 och 10,7 meter samt en vikt mellan 5,8 och 9,1 ton. I genomsnitt är honor en meter längre än hannar. Nyfödda ungar är 2,4 till 2,8 meter långa.[3]

Valen är på ovansidan mörkgrå och på undersidan vitaktig. Bröstfenorna är mörka med vita kanter. På så sätt skiljer sig arten från den vanliga vikvalen som har en vit strimma i mitten av bröstfenorna. Även i färgsättningen av andra kroppsdelar skiljer de sig lite från varandra.[3]

Se även: Valfångst

Den första individen av antarktisk vikval fångades (det registrerades inte om den var en vanlig vikval eller en antarktisk vikval, men det var troligen den senare) av ett brittiskt fartyg under säsongen 1950/51. Antalet ökade och under säsongen 1957/58 dödades 493 individer. Liknande antal fångades under de följande åren med undantag av säsongen 1967/68 med en fångst på 605 valar. 1971/72 dödades 3 021 antarktiska vikvalar. För att bevara beståndet bestämde den internationella valfångstkommissionen (IWC) en kvot på 5 000 individer för säsongen 1972/73 men värdet överskreds med 745 valar.

Antarktisk vikval (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) är en art i familjen fenvalar som i sin tur tillhör underordningen bardvalar.

Antarktika minke balinası (Balaenoptera bonaerensis), oluklu balinagiller (Balaenopteridae) familyasına ait balina türü.

Bayağı minke balinasından biraz daha küçüktür. 7.2 - 10.7 m uzunluğunda ve 5.8 - 9.1 ton ağırlığındadır. Dişileri erkeklerden yaklaşık 1 m daha uzundur. Yenidoğan yavrular 2.4 - 2.8 m dir. Sırtı koyu gri karnı ise beyazdır

Güney Yarıküre okyanuslarında yayılım gösterir.

Antarktika minke balinası (Balaenoptera bonaerensis), oluklu balinagiller (Balaenopteridae) familyasına ait balina türü.

Середня довжина самців: 8,5 м, вага — 6,85 тонн, максимальна довжина: 9.63 м. Середня довжина самиць: 9 м, максимальна довжина: 10.7 м, вага до 10 тонн.

Верхня сторона тіла темно-сіра, підчерев'я білого кольору, зі світлими прожилками на боках і блідими плавниками. Рострум вузький і загострений. Спинний плавець крючковидий і знаходиться приблизно на 2/3 довжини тіла від переду. Антарктичні смугачі мають більші черепа, ніж смугач малий.

Знайдений у всіх океанах південної півкулі; живе в прибережних і морських водах. У літню пору цей вид зустрічається поблизу кромки льоду або серед дрейфуючих льодів і в ополонках. Протягом літа, цей вид збирається з високою щільністю в антарктичних водах, щоб харчуватися, в той час як протягом зими він рухається на північ, в більш тропічні або помірні води, щоб розмножуватися. Не всі антарктичні смугачі мігрують і деякі з них можуть зимувати в Антарктиці.

Зустрічається поодинці або парами, хоча скупчення у сотню китів може відбутися під час годівлі. Дієта складається в основному з криля (близько 94 % за вагою, інша здобич — Euphasi frigida і Thysanoessa macrura). У свою чергу на них можуть полювати косатки (Orcinus orca). B. bonaerensis може плавати зі швидкістю до 20 кілометрів на годину і може занурюватися під воду до 20 хвилин, хоча його занурення зазвичай тривають всього кілька хвилин. Це допитливий вид і, як відомо, часто підходить до човнів. Для комунікації виробляє широкий спектр звуків.

Період розмноження: зима. Період вагітності становить десять місяців. Як правило народжується одне дитинчати, хоча близнюки і трійнята можуть іноді траплятися. Дитинчата звичайно ссуть молоко протягом п'яти місяців і залишаються з матір'ю на строк до двох років. Молодь досягає статевої зрілості у віці від 7 до 8 років. Тривалість життя близько 50 років. Найстарішому дослідженому антарктичному смугачу було 73 років.