pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

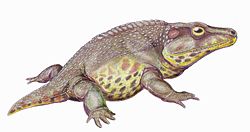

Els dissoròfids (Dissorophidae) són un tàxon extint d'amfibis temnospòndils de mida mitjana que van prosperar a Europa i Nord-amèrica a principis del Permià. Malgrat que eren amfibis, sembla que estaven ben adaptats a la vida sobre la terra, amb potes ben desenvolupades, vèrtebres sòlides, i una filera de plaques d'armadura fetes d'os dèrmic, que protegia l'animal i n'enrobustia l'esquena.

Un gènere ben conegut és Cacops, un animal de finals del Permià Inferior, i que vivia a Texas. Tenia un cap relativament gran, i la típica filera d'armadura a l'esquena. En el gènere similar però més gran i més especialitzat, Platyhystrix, que vivia a Utah, Colorado i Nou Mèxic, l'armadura va desenvolupar-se en una mena de vela.

Hi ha algunes formes relacionades que semblen haver estat més aquàtiques, conegudes del Permià Superior de Rússia i el Triàsic Inferior de Gondwana.

S'ha suggerit que els dissoròfids poden estar relacionats amb els avantpassats de les granotes, a través de formes intermèdies com Doleserpeton.

Els dissoròfids (Dissorophidae) són un tàxon extint d'amfibis temnospòndils de mida mitjana que van prosperar a Europa i Nord-amèrica a principis del Permià. Malgrat que eren amfibis, sembla que estaven ben adaptats a la vida sobre la terra, amb potes ben desenvolupades, vèrtebres sòlides, i una filera de plaques d'armadura fetes d'os dèrmic, que protegia l'animal i n'enrobustia l'esquena.

Un gènere ben conegut és Cacops, un animal de finals del Permià Inferior, i que vivia a Texas. Tenia un cap relativament gran, i la típica filera d'armadura a l'esquena. En el gènere similar però més gran i més especialitzat, Platyhystrix, que vivia a Utah, Colorado i Nou Mèxic, l'armadura va desenvolupar-se en una mena de vela.

Hi ha algunes formes relacionades que semblen haver estat més aquàtiques, conegudes del Permià Superior de Rússia i el Triàsic Inferior de Gondwana.

S'ha suggerit que els dissoròfids poden estar relacionats amb els avantpassats de les granotes, a través de formes intermèdies com Doleserpeton.

Dissorophidae is an extinct family of medium-sized, temnospondyl amphibians that flourished during the late Carboniferous and early Permian periods. The clade is known almost exclusively from North America.

Dissorophidae is a diverse clade that was named in 1902 by George A. Boulenger. Junior synonyms include Otocoelidae, Stegopidae, and Aspidosauridae.[1] Early in the study of dissorophoids when the relationships of different taxa were not well-resolved and most taxa had not been described, Dissorophidae sometimes came to include taxa that are now not regarded as dissorophids and may have excluded earlier described taxa that are now regarded as dissorophids. Amphibamiforms were widely regarded as small-bodied dissorophids,[2] and at one point, Dissorophidae was also suggested to also include Trematopidae.[3]

In 1895, American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope named Dissorophus from the early Permian of Texas. This was the first dissorophid to be described as such, although Parioxys, named by Cope in 1878, and Zygosaurus, named by the Russian paleontologist Karl von Eichwald in 1848, have also been regarded as dissorophids. A second species of Dissorophus as well as both species of the genus Otocoelus that were all named in 1896 by Cope in two papers are now regarded as junior synonyms of the type species of Dissorophus, D. multicinctus.

The early 20th century saw a large expansion in the study of dissorophids. In 1904, German paleontologist Ferdinand Broili named the first species of Aspidosaurus, A. chiton, from the early Permian of Texas. Additional species of Aspidosaurus were named shortly thereafter, including Aspidosaurus glascocki from the early Permian of Texas and Aspidosaurus novomexicanus from the late Carboniferous of New Mexico. A third species, "Aspidosaurus crucifer" described by American paleontologist E.C. Case is now regarded as an indeterminate aspidosaurine. In 1910, two of the best-known dissorophid genera were named: Cacops aspidephorus[4] and Platyhystrix (as a species of Ctenosaurus;[5] proper name erected in 1911). Case also provided new information on Dissorophus in 1910.[6] In 1911, Case named Alegeinosaurus aphthitos from the early Permian of Texas.[7] In 1914, Samuel W. Williston described the first species of Broiliellus, B. texensis.[8] Additional information on Parioxys ferricolus was provided in two studies by Egyptian paleontologist Y.S. Moustafa in 1955.[9][10]

The 1960s were a particular productive time for dissorophid research. In two separate papers published in 1964, Canadian paleontologist Robert L. Carroll named four new taxa: Brevidorsum profundum, Broiliellus brevis, and Parioxys bolli from the early Permian of Texas and Conjunctio multidens from the early Permian of New Mexico.[11][12] Conjunctio was named from a specimen originally referred to Aspidosaurus novomexicanus by Case et al. (1913)[13] that was also placed in Broiliellus by American paleontologist Wann Langston in 1953[14] before being divided again by Carroll. In 1965, American paleontologist E.C. Olson described the first and only middle Permian dissorophid from North America, Fayella chickashaensis, on the basis of an isolated braincase and isolated fragments. A large postcranial skeleton from a different locality was referred to this taxon by Olson in 1972. In 1966, American paleontologist Robert E. DeMar named a new taxon, "Longiscitula houghae" from the early Permian of Texas;[15] this is now regarded as a junior synonym of Dissorophus multicinctus by British paleontologist Andrew Milner.[16] DeMar also provided the first synthesis of the morphological diversity and possible function of dissorophid osteoderms in 1966[17] and named two new species of Broiliellus in 1967, B. arroyoensis and B. olsoni,[18] and completed a detailed revision of D. multicinctus in 1968.[19]

In 1971, American paleontologist Peter Vaughn described one of the few dissorophids outside of New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma, Astreptorhachis ohioensis from the late Carboniferous of Ohio, represented by a series of fused neural spines and osteoderms.[20] American paleontologist John Bolt published a survey of dissorophid osteoderms in 1974 with an emphasis on taxonomic utility and differentiation and reports of material from the early Permian Richards Spur locality in Oklahoma;[21] in 1977, Bolt reported Cacops from the locality.[22] In 1980, Russian paleontologist Yuri Gubin described two new middle Permian dissorophids from Russia: Iratusaurus vorax and Kamacops acervalis.[23] The most complete cranial material of Platyhystrix rugosus was described in 1981 by a team led by American paleontologist David Berman.[24] Additional postcranial material of Platyhystrix, primarily the characteristic hyperelongate spines, was also periodically reported.[25][26][27] The revision of Ecolsonia cutlerensis in 1985 by Berman and colleagues placed the taxon as a dissorophid, but this taxon is more often recovered as a trematopid.[28] In 1999, Chinese paleontologists Li Jinling and Cheng Zhengwu described the first and only dissorophid from eastern Asia, the middle Permian Anakamacops petrolicus from China.[29]

In 2003, American paleontologists Berman and Spencer G. Lucas named a new species of Aspidosaurus from Texas, A. binasser.[30] Two papers on the osteoderm biomechanics of Cacops aspidephorus and Dissorophus multicinctus, led by Canadian paleontologist David Dilkes, were published in 2007 and 2009.[31][32] In 2009, a team led by Canadian paleontologist Robert Reisz described a new species of Cacops, C. morrisi, from the Richards Spur locality;[33] additional material of this taxon was described in 2018 by American paleontologist Bryan M. Gee and Reisz.[34] A second species from the locality was described in 2012 by German paleontologist Nadia B. Fröbisch and Reisz, C. woehri;[35] additional material of Cacops woehri was described in 2015 by a team led by Fröbisch.[36] A team led by German paleontologist Florian Witzmann published a comparative histology study that sampled a number of dissorophids in 2010.[37] May et al. (2011) described material of Aspidosaurus from the late Carboniferous of the mid-continent of North America.[38] The first phylogenetic review of the Dissorophidae was published in 2012 by Schoch.[39] In 2013, three new dissorophids were named in a festschrift dedicated to Reisz in Comptes Rendus Palévol: Broiliellus reiszi from the early Permian of New Mexico in a study led by Canadian paleontologist Robert Holmes;[40] Scapanops neglecta from the early Permian of Texas in a study by German paleontologists Schoch and Hans-Dieter Sues, re-evaluating a specimen historically referred to as the Admiral Taxon;[41] and Reiszerpeton renascentis from the early Permian of Texas in a review of material referred to the amphibamiform Tersomius texensis by a team led by Canadian paleontologist Hillary C. Maddin.[42] In 2018, Chinese paleontologist Liu Jun provided an updated osteology of Anakamacops based on substantially more complete material and erected the tribe Kamacopini to group the middle Permian dissorophids from Eurasia.[43] Two separate studies led by Gee were also published that year, one reappraising the early Permian Alegeinosaurus aphthitos from Texas, which he suggested to be a junior synonym of Aspidosaurus,[44] and another reappraising the middle Permian Fayella chickashaensis from Oklahoma, in which the authors determined that the holotype was a nomen dubium but that the referred specimen was sufficiently distinct to warrant erecting a new taxon, Nooxobeia gracilis.[45] Also in 2018, Gee and Reisz reported postcrania of a large indeterminate dissorophid from Richards Spur,[46] which was followed by another study the following year by a team led by Gee that reported extensive new material from several dissorophids from Richards Spur, including the first documentation of Aspidosaurus and Dissorophus from the locality.[47]

Dissorophids are most readily recognized for their distinctive osteoderms, although these are not unique to either dissorophids among temnospondyls or to temnospondyls among early tetrapods. It is also debated whether Platyhystrix has true osteoderms or simply ornamented neural spines with similar morphology to the ornamentation of osteoderms in other taxa. There is also great variability in the osteoderms, both in the number of series and in the overall proportions and anatomy. Dissorophines like Dissorophus typically possess wide osteoderms in contrast to eucacopines like Cacops.[32] Both groups have two series of osteoderms that are relatively flat, in contrast to aspidosaurines, which purportedly a single series that is dorsally keeled to form an inverted-V morphology; it has been suggested, based on CT data, that at least some aspidosaurines may actually have two series of osteoderms but that one is largely obscured.[47] Although osteoderm morphology has been shown to not exert a discernible influence on dissorophid phylogeny,[39] osteoderms remain a major hallmark used to differentiate major clades within Dissorophidae and remain useful for establishing the monophyly of the group within Dissorophoidea. Schoch & Milner (2014) list several features that diagnose dissorophids, but most of these are only useful for differentiating the clade from the closely related trematopids, and some are outdated in light of newer research: (1) maxillary tooth row terminating at or anterior to the posterior orbital margin; (2) basipterygoid region firmly sutured; (3) no prefrontal-postfrontal contact; (4) absence of denticles on the basal plate of the parasphenoid; (5) no pterygoid-vomer contact; (6) short postorbital; (7) long and parallel-sided choana; and (8) absence of a supinator process.[1]

Aspidosaurines and platyhystricines are represented largely by postcranial material, and thus features such as osteoderms are some of the only differentiators for these taxa, but dissorophines and eucacopiens also have many cranial differences, such as the relative proportions of the skull. Most dissorophids are medium-sized, being intermediate between the small amphibamiforms and the larger trematopids, but Dissorophidae includes the largest known dissorophoids, all from the middle Permian of Eurasia, with skull lengths exceeding 30 cm.

Below is a timeline of the known fossil ranges of dissorophids.[48]

Four subfamilies comprise the various dissorophids. Eucacopine (sensu Schoch & Sues, 2013) was traditionally referred to as Cacopinae and includes Cacops and the middle Permian Eurasian taxa (Anakamacops, Iratusaurus, Kamacops, Zygosaurus).[41][43] Dissorophinae[4] includes Dissorophus and all four species of Broiliellus. These are the two most widely utilized distinctions within Dissorophidae, although Aspidosaurinae[8] (which includes only Aspidosaurus and indeterminate Aspidosaurus-like material) was recently revived along with the erection of the new Platyhystricinae (Platyhystrix and Astreptorhachis).[1] The placement of some more poorly known (Brevidorsum) or anatomically distinct (Scapanops) taxa is less resolved.

Below is a cladogram from Schoch (2012):[49]

Dissorophoidea Micromelerpetontidae Amphibamidae Olsoniformes Trematopidae Dissorophidae Dissorophinae EucacopinaeAdmiral taxon (Scapanops)

Rio Arriba taxon (Conjunctio)

Platyhystrix rugosus, a platyhystricine of the very late Carboniferous to early Permian of North America

Nooxobeia gracilis, an unusually long-legged dissorophid of the early Permian of Oklahoma

Broiliellus olsoni, a dissorophine of the early Permian of Texas

Cacops aspidephorus, a eucacopine of the early Permian of Texas

Zygosaurus lucius, a eucacopine of the middle Permian of Russia

Kamacops acervalis, a eucacopine of the middle Permian of Russia

Anakamacops petrolicus, a eucacopine of the middle Permian of China

{{cite book}}: |last= has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) {{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Dissorophidae is an extinct family of medium-sized, temnospondyl amphibians that flourished during the late Carboniferous and early Permian periods. The clade is known almost exclusively from North America.

Dissorophidae es un grupo extinto de temnospóndilos que florecieron desde finales del período Carbonífero hasta finales del período Pérmico, distribuyéndose en lo que hoy es Norteamérica y Rusia. Estaban bien adaptados al medio terrestre, con desarrolladas y robustas extremidades, vértebras sólidas y una fila de placas a modo de armadura en la región dorsal. Se ha sugerido que Dissorophoidea puede corresponder a los ancestros de los anuros o incluso de todos los lisanfibios, con formas intermedias representadas por géneros como Doleserpeton.

Dissorophidae es un grupo extinto de temnospóndilos que florecieron desde finales del período Carbonífero hasta finales del período Pérmico, distribuyéndose en lo que hoy es Norteamérica y Rusia. Estaban bien adaptados al medio terrestre, con desarrolladas y robustas extremidades, vértebras sólidas y una fila de placas a modo de armadura en la región dorsal. Se ha sugerido que Dissorophoidea puede corresponder a los ancestros de los anuros o incluso de todos los lisanfibios, con formas intermedias representadas por géneros como Doleserpeton.

Dissorophidae ou dissophoridés est une famille d'amphibiens fossiles de l'ordre des Temnospondyli. C'était des animaux de taille moyenne qui ont prospéré à la fin du Pennsylvanien et au début du Permien dans ce qui est maintenant l'Amérique du Nord et l'Europe. Même s'il s'agissait d'amphibiens, ils semblent avoir été bien adaptés à la vie sur terre, avec des membres bien développés, des vertèbres solides, et une rangée de plaques dermiques qui tout à la fois protégeait l'animal et renforçait la colonne vertébrale.

Un genre bien connu est Cacops, un genre d'animal trapu ayant vécu à la fin du début du Permien (à l'Artinskien) dans le Groupe de Clear Fork au Texas. Il avait une tête relativement énorme et une rangée de plaques de blindage sur le dos. Dans un genre similaire mais légèrement plus grand et plus spécialisé, Platyhystrix, dont les restes fossiles ont été trouvés dans le Groupe Cutler en Utah, Colorado et au Nouveau-Mexique, l'armure se présentant sous la forme d'une crête ou d'une voile.

Tous les Dissorophidés n'étaient pas de grands animaux au corps trapu avec de grosses têtes. Le genre Fayella, ayant vécu à la fin de l'Artinskien dans l'Oklahoma, était de construction légère avec de longs membres, s'appuyant de toute évidence sur la vitesse plutôt que sur le blindage comme moyen de défense contre les prédateurs.

Il y a également un certain nombre de formes apparentées qui semblent avoir été plus aquatiques. Celles-ci sont connues pour avoir vécu à la fin du Permien en Russie et au Trias inférieur au Gondwana.

On a suggéré que les Dissorophidae peuvent avoir été proches des ancêtres des grenouilles, via des formes intermédiaires, comme Doleserpeton.

Dissorophidae ou dissophoridés est une famille d'amphibiens fossiles de l'ordre des Temnospondyli. C'était des animaux de taille moyenne qui ont prospéré à la fin du Pennsylvanien et au début du Permien dans ce qui est maintenant l'Amérique du Nord et l'Europe. Même s'il s'agissait d'amphibiens, ils semblent avoir été bien adaptés à la vie sur terre, avec des membres bien développés, des vertèbres solides, et une rangée de plaques dermiques qui tout à la fois protégeait l'animal et renforçait la colonne vertébrale.

Un genre bien connu est Cacops, un genre d'animal trapu ayant vécu à la fin du début du Permien (à l'Artinskien) dans le Groupe de Clear Fork au Texas. Il avait une tête relativement énorme et une rangée de plaques de blindage sur le dos. Dans un genre similaire mais légèrement plus grand et plus spécialisé, Platyhystrix, dont les restes fossiles ont été trouvés dans le Groupe Cutler en Utah, Colorado et au Nouveau-Mexique, l'armure se présentant sous la forme d'une crête ou d'une voile.

Tous les Dissorophidés n'étaient pas de grands animaux au corps trapu avec de grosses têtes. Le genre Fayella, ayant vécu à la fin de l'Artinskien dans l'Oklahoma, était de construction légère avec de longs membres, s'appuyant de toute évidence sur la vitesse plutôt que sur le blindage comme moyen de défense contre les prédateurs.

Il y a également un certain nombre de formes apparentées qui semblent avoir été plus aquatiques. Celles-ci sont connues pour avoir vécu à la fin du Permien en Russie et au Trias inférieur au Gondwana.

On a suggéré que les Dissorophidae peuvent avoir été proches des ancêtres des grenouilles, via des formes intermédiaires, comme Doleserpeton.

Dissorophidea é un taxón extinguido de anfibios Temnospondyli de medida mediana que prosperaron en Europa e América do Norte a principios do Permiano. Malia que eran anfibios, parece que estaban ben adaptados á vida sobre a terra, con patas ben desenvolvidas, vértebras sólidas, e unha fileira de placas de armadura feitas de óso dérmico, que protexía o animal e robustecía as costas.

I dissorofidi (Dissorophidae) sono una famiglia di anfibi estinti, vissuti tra il Carbonifero superiore e il Permiano superiore (310 – 250 milioni di anni fa). I loro resti sono stati rinvenuti in Nordamerica ed Europa.

Di dimensioni relativamente piccole (di norma non superavano i 60 centimetri di lunghezza), i dissorofidi possedevano caratteristiche notevolmente diverse da quelle degli altri anfibi tipici del Carbonifero e del Permiano. Nonostante i loro parenti prossimi fossero giganteschi predoni semiacquatici come Eryops, i dissorofidi svilupparono zampe corte ma potenti, adatte alla locomozione terrestre, e i loro corpi erano piccoli e compatti. La testa, al contrario, era eccezionalmente grossa in rapporto al resto del corpo, ed era armata di ampie fauci.

Il cranio era dotato di una notevole incisura otica, che indica la presenza di una notevole membrana timpanica e quindi di un ottimo udito. La maggior parte dei dissorofidi, inoltre, era dotata di una spessa corazza lungo il dorso, che garantiva una protezione contro predatori terrestri quali gli sfenacodonti. Probabilmente i dissorofidi erano piccoli predatori terrestri, che catturavano invertebrati e piccoli vertebrati grazie a rapidi movimenti.

Tra le forme più conosciute, da ricordare Cacops, presente nei terreni del Permiano nordamericano, così come l'insolito Platyhystrix munito di “vela”. Dissorophus, che dà il nome alla famiglia, è leggermente più antico. Non tutti i dissorofidi avevano un corpo compatto e zampe corte: Nooxobeia, ad esempio, era snello e leggero; le sue zampe allungate gli permettevano di affidarsi alla velocità, e non all'armatura, per sfuggire ai predatori.

In Russia, in strati del Permiano medio e superiore, sono state rinvenute numerose forme di dimensioni piuttosto cospicue che potrebbero appartenere a questa famiglia: tra queste Zygosaurus e Kamacops, particolarmente affine a Cacops. I dissorofidi potrebbero essere sopravvissuti all'estinzione di fine Permiano, se è vero che i resti di un animale, denominato Micropholis stowi e risalente al Triassico inferiore del Sudafrica, appartengono a questa famiglia. In ogni caso, sembra che queste ultime forme fossero più legate all'ambiente acquatico.

Alcuni scienziati ritengono che i dissorofidi fossero vicini all'origine delle rane (Anura); in particolare alcune forme intermedie, come Doleserpeton, potrebbero essere le dirette antenate degli odierni anfibi.

I dissorofidi (Dissorophidae) sono una famiglia di anfibi estinti, vissuti tra il Carbonifero superiore e il Permiano superiore (310 – 250 milioni di anni fa). I loro resti sono stati rinvenuti in Nordamerica ed Europa.

Dissorophidae – rodzina wymarłych płazów z rzędu Temnospondyli. Żyły one w późnym pensylwanie i wczesnym permie na lądach dziś znanych jako Europa i Ameryka Północna. Mimo że zalicza się je do płazów, dobrze przystosowały się do środowiska lądowego, wykształcając dobrze rozwinięte kończyny, solidne kręgi, a także rząd płyt na grzbiecie chroniący zwierzę i wzmacniający kręgosłup.

Dobrze znany rodzaj stanowi Cacops, przysadziste solidnie zbudowane zwierzę z wczesnego permu (artinsk) z Teksasu. Miał on względnie dużą głowę i wspomniany już rząd płyt na grzbiecie. Bardzo podobny, ale nieco większy i bardziej wyspecjalizowany był Platyhystrix, którego skamieniałości znaleziono w Utah, Kolorado i Nowym Meksyku. Nosił on na grzbiecie żagiel z płyt.

Nie wszystkie zwierzęta z tej grupy były przysadzistymi dużogłowymi stworzeniami. Fayella z późnego artinska z Oklahomy posiadała lekką budowę i długie łapy. To raczej prędkość, a nie ochronne płyty chroniły ją przed drapieżnikami.

Wiele spokrewnionych form wydaje się być bardziej wodnymi, pochodzą z późnego permu (dzisiejsza Rosja), a nawet wczesnego triasu z Gondwany.

Zasugerowano, że stworzenia te mogły być blisko spokrewnione z przodkami dzisiejszych żab, za formy pośrednie uchodzą takie zwierzęta, jak Doleserpeton.

Dissorophidae – rodzina wymarłych płazów z rzędu Temnospondyli. Żyły one w późnym pensylwanie i wczesnym permie na lądach dziś znanych jako Europa i Ameryka Północna. Mimo że zalicza się je do płazów, dobrze przystosowały się do środowiska lądowego, wykształcając dobrze rozwinięte kończyny, solidne kręgi, a także rząd płyt na grzbiecie chroniący zwierzę i wzmacniający kręgosłup.

Dobrze znany rodzaj stanowi Cacops, przysadziste solidnie zbudowane zwierzę z wczesnego permu (artinsk) z Teksasu. Miał on względnie dużą głowę i wspomniany już rząd płyt na grzbiecie. Bardzo podobny, ale nieco większy i bardziej wyspecjalizowany był Platyhystrix, którego skamieniałości znaleziono w Utah, Kolorado i Nowym Meksyku. Nosił on na grzbiecie żagiel z płyt.

Nie wszystkie zwierzęta z tej grupy były przysadzistymi dużogłowymi stworzeniami. Fayella z późnego artinska z Oklahomy posiadała lekką budowę i długie łapy. To raczej prędkość, a nie ochronne płyty chroniły ją przed drapieżnikami.

Wiele spokrewnionych form wydaje się być bardziej wodnymi, pochodzą z późnego permu (dzisiejsza Rosja), a nawet wczesnego triasu z Gondwany.

Zasugerowano, że stworzenia te mogły być blisko spokrewnione z przodkami dzisiejszych żab, za formy pośrednie uchodzą takie zwierzęta, jak Doleserpeton.

Dissorophidae é uma família extinta de anfíbios temnospondyli de tamanho médio que viveram durante os últimos períodos carbonífero e inicial do Permiano. O clado é conhecido quase exclusivamente da América do Norte.

Dissorophidae é um clado diverso que foi nomeado em 1902 por George A. Boulenger. Os sinônimos júnior incluem Otocoelidae, Stegopidae e Aspidosauridae.[1] No início do estudo dos dissorofídeos, quando as relações de diferentes táxons não estavam bem resolvidas e a maioria dos táxons não havia sido descrita, às vezes Dissorophidae passou a incluir táxons que agora não são considerados dissorofídeos e podem ter excluído táxons descritos anteriormente que agora são considerados dissorofídeos. Os anfibamiformes foram amplamente considerados dissorofídeos de corpo pequeno[2] e, a certa altura, Dissorophidae também foi sugerido para incluir também Trematopidae.[3]

Em 1895, o paleontólogo americano Edward Drinker Cope nomeou Dissorophus do início do Permiano do Texas. Este foi o primeiro dissorofídeo a ser descrito como tal, embora Parioxys, nomeado por Cope em 1878, e Zygosaurus, nomeado pelo paleontólogo russo Karl von Eichwald em 1848, também tenham sido considerados dissorofídeos. Uma segunda espécie de Dissorophus, bem como as duas espécies do gênero Otocoelus que foram nomeadas em 1896 por Cope em dois artigos, são agora consideradas sinônimos juniores da espécie de espécie de Dissorophus, D. multicinctus.

O início do século 20 viu uma grande expansão no estudo dos dissorofídeos. Em 1904, o paleontólogo alemão Ferdinand Broili nomeou a primeira espécie de Aspidosaurus, A. chiton, do início do Permiano do Texas. Outras espécies de Aspidosaurus foram nomeadas logo depois, incluindo Aspidosaurus glascocki, do Permiano do Texas e Aspidosaurus novomexicanus, do Carbonífero do Novo México. Uma terceira espécie, "Aspidosaurus crucifer", descrita pelo paleontologista americano E. C. Case, é agora considerada uma aspidosaurina indeterminada. Em 1910, dois dos gêneros dissorofídeos mais conhecidos foram nomeados: Cacops aspidephorus[4] e Platyhystrix (como uma espécie de Ctenosaurus;[5] nome próprio erigido em 1911). Case também forneceu novas informações sobre Dissorophus em 1910.[6] Em 1911, Case nomeou Alegeinosaurus aphthitos do início do Permiano do Texas.[7] Em 1914, Samuel W. Williston descreveu a primeira espécie de Broiliellus, B. texensis.[8] Informações adicionais sobre Parioxys ferricolus foram fornecidas em dois estudos pelo paleontólogo egípcio Y.S. Moustafa em 1955.[9][10]

A década de 1960 foi um período produtivo específico para pesquisas dos dissorofídeos. Em dois artigos publicados em 1964, o paleontólogo canadense Robert L. Carroll nomeou quatro novos táxons: Brevidorsum profundum, Broiliellus brevis e Parioxys bolli, do Permiano do Texas e Conjunctio multidens, do Permiano do Novo México.[11][12] Conjunção foi nomeada a partir de um espécime originalmente referido como Aspidosaurus novomexicanus por Case et al. (1913)[13] que também foi colocado em Broiliellus pelo paleontólogo americano Wann Langston em 1953[14] antes de ser dividido novamente por Carroll. Em 1965, o paleontólogo americano E.C. Olson descreveu o primeiro e único dissorofídeo permiano médio da América do Norte, Fayella chickashaensis, com base em uma base cerebral isolada e fragmentos isolados. Um grande esqueleto pós-craniano de uma localidade diferente foi referido por Olson em 1972. Em 1966, o paleontólogo americano Robert E. DeMar nomeou um novo táxon, "Longiscitula houghae", do início do Permiano do Texas;[15] agora isso é considerado um sinônimo júnior de Dissorophus multicinctus pelo paleontólogo britânico Andrew Milner.[16] DeMar também forneceu a primeira síntese da diversidade morfológica e possível função dos osteodérmicos dissorofídeos em 1966[17] e nomeou duas novas espécies de Broiliellus em 1967, B. arroyoensis e B. olsoni[18] e concluiu uma revisão detalhada de D. multicinctus em 1968.[19]

Em 1971, o paleontólogo americano Peter Vaughn descreveu um dos poucos dissorofídeos fora do Novo México, Texas e Oklahoma, Astreptorhachis ohioensis, do falecido Carbonífero de Ohio, representado por uma série de espinhas neurais e osteodermes fundidos.[20] O paleontólogo americano John Bolt publicou uma pesquisa sobre osteodérmicos dissorofídeos em 1974, com ênfase na utilidade taxonômica, diferenciação e relatórios de material da antiga localidade de Permian Richards Spur em Oklahoma;[21] em 1977, Bolt relatou Cacops da localidade.[22] Em 1980, o paleontólogo russo Yuri Gubin descreveu dois novos dissorofídeos do Permiano da Rússia: Iratusaurus vorax e Kamacops acervalis.[23] O material craniano mais completo do Platyhystrix rugosus foi descrito em 1981 por uma equipe liderada pelo paleontólogo americano David Berman.[24] Também foi relatado periodicamente material pós-craniano adicional de Platyhystrix, principalmente as espinhas hiperelongadas características.[25][26][27] A revisão de Ecolsonia cutlerensis em 1985 por Berman e colegas colocou o táxon como um dissorofídeo, mas esse táxon é mais frequentemente recuperado como um trematopídeo.[28] Em 1999, os paleontólogos chineses Li Jinling e Cheng Zhengwu descreveram o primeiro e único dissorofídeo do leste da Ásia, o Permiano Anakamacops petrolicus da China.[29]

Em 2003, os paleontólogos americanos Berman e Spencer G. Lucas nomearam uma nova espécie de Aspidosaurus do Texas, A. binasser.[30] Dois artigos sobre a biomecânica osteoderma de Cacops aspidephorus e Dissorophus multicinctus, liderados pelo paleontólogo canadense David Dilkes, foram publicados em 2007 e 2009.[31][32] Em 2009, uma equipe liderada pelo paleontólogo canadense Robert Reisz descreveu uma nova espécie de Cacops, C. morrisi, da localidade Richards Spur;[33] material adicional deste táxon foi descrito em 2018 pelo paleontólogo americano Bryan M. Gee e Reisz.[34] Uma segunda espécie da localidade foi descrita em 2012 pela paleontóloga alemã Nadia B. Fröbisch e Reisz, C. woehri;[35] material adicional de Cacops woehri foi descrito em 2015 por uma equipe liderada por Fröbisch.[36] Uma equipe liderada pelo paleontologista alemão Florian Witzmann publicou um estudo comparativo de histologia que amostrou vários dissorofídeos em 2010.[37] May et al. (2011) descreveram material do Aspidosaurus do Carbonífero tardio do meio-continente da América do Norte.[38] A primeira revisão filogenética dos Dissorophidae foi publicada em 2012 por Schoch.[39] Em 2013, três novos dissorofídeos foram nomeados em uma festa dedicada a Reisz no Comptes Rendus Paleovol: Broiliellus reiszi, do início do Permiano do Novo México, em um estudo liderado pelo paleontólogo canadense Robert Holmes;[40] Scapanops neglecta, do início do Permiano do Texas, em um estudo dos paleontólogos alemães Schoch e Hans-Dieter Sues, reavaliando um espécime historicamente chamado de Almirante Taxon;[41] e Reiszerpeton renascentis, do início do Permiano do Texas, em uma revisão do material referido ao anfibamiforme Tersomius texensis por uma equipe liderada pela paleontologista canadense Hillary C. Maddin.[42] Em 2018, o paleontólogo chinês Liu Jun forneceu uma osteologia atualizada de Anakamacops com base em material substancialmente mais completo e ergueu a tribo Kamacopini para agrupar os dissorofídeos do Permiano Médio da Eurásia.[43] Dois estudos separados liderados por Gee também foram publicados naquele ano, um reavaliando os primeiros Alegeinosaurus aphthitos de Permiano do Texas, que ele sugeriu ser um sinônimo júnior de Aspidosaurus,[44] e outro reavaliando o Permiano Médio Fayella chickashaensis de Oklahoma, no qual o os autores determinaram que o holótipo era um nomen dubium, mas que o espécime referido era suficientemente distinto para garantir a construção de um novo táxon, Nooxobeia gracilis.[45] Também em 2018, Gee e Reisz relataram pós-grânulos de um grande dissorofídeo indeterminado de Richards Spur,[46] seguido por outro estudo no ano seguinte por uma equipe liderada por Gee que relatou um extenso material novo de vários dissorofídeos de Richards Spur, incluindo o primeira documentação de Aspidosaurus e Dissorophus da localidade.[47]

Abaixo está uma linha do tempo das faixas fósseis conhecidas de dissorofídeos.[48]

Quatro subfamílias compreendem os vários dissorofídeos. A eucacopina (sensu Schoch & Sues, 2013) era tradicionalmente referida como Cacopinae e inclui Cacops e os táxons da Eurásia do Permiano Médio (Anakamacops, Iratusaurus, Kamacops, Zygosaurus).[41][43] Dissorophinae[4] inclui Dissorophus e todas as quatro espécies de Broiliellus. Essas são as duas distinções mais amplamente utilizadas em Dissorophidae, embora Aspidosaurinae[8] (que inclui apenas Aspidosaurus e material indeterminado semelhante a Aspidosaurus) tenha sido recentemente revivido juntamente com a ereção da nova Platyhystricinae (Platyhystricinae e Astreptorhachis).[1] A colocação de alguns táxons mais pouco conhecidos (Brevidorsum) ou anatomicamente distintos (Scapanops) é menos resolvida.

Abaixo está um cladograma de Schoch (2012):[49]

Dissorophoidea MicromelerpetontidaeAdmiral taxon (Scapanops)

Rio Arriba taxon (Conjunctio)

Dissorophidae é uma família extinta de anfíbios temnospondyli de tamanho médio que viveram durante os últimos períodos carbonífero e inicial do Permiano. O clado é conhecido quase exclusivamente da América do Norte.

Диссорофиды (Dissorophidae) — семейство темноспондилов позднего карбона — перми. Наиболее наземные из всех темноспондилов. Скелет массивный, тело короткое, конечности длинные, сильные. Голова огромная относительно размеров тела. Череп высокий и широкий, огромные глазницы, крупное теменное отверстие. Огромные ушные вырезки, судя по строению окружающей кости, содержали барабанную перепонку. Затылочный мыщелок парный. Челюстное сочленение на уровне затылочного. Скульптура черепа гребнистая. Края орбит и теменного отверстия окружены костными валиками, что предполагает толстую кожу. У большинства известен дермальный панцирь на спине из парных рядов костных пластин, приросших к остистым отросткам позвонков, у какопса пластины лежали в два слоя (внутренний слой прирастал к позвонкам). Кожа, по-видимому, мягкая, следов чешуи не выявлено. Хвост короткий. Вероятно, прибрежные амфибиотические и полуназемные хищники. Есть свидетельства (следы зубов на костях), что крупные диссорофиды могли питаться и падалью.

Не менее 15 родов, из позднего карбона — средней перми Северного полушария. Большинство родов описано из ранней перми Северной Америки.

Наиболее известен род какопс (Cacops) с единственным видом C. aspidephorus, описанным Сэмюэлем Виллистоном в 1910 году из ранней перми (клир-форк) Техаса. Скелет часто изображают в литературе. Длина черепа около 20 см, общая длина до 50 см. Виллистон считал какопса ночным животным из-за очень крупных глазниц. Череп слегка удлинённый, высокий, сжатый с боков. Ноздри крупные, сближенные. Огромные ушные вырезки. Есть пре- и постхоанные небные клыки, наружная крыловидная кость без зубов. 21 предкрестцовый позвонок, 2 крестцовых, 21—22 хвостовых. Пластинки спинного панциря соединены друг с другом и с остистыми отростками, слегка шире позвонков.

Описанный в 1980 году Ю. М. Губиным камакопс (Kamacops acervalis) из средней перми Пермской области (очёрская фауна) — ближайший родственник какопса. От своего американского родича отличается более крупными размерами (череп до 25—30 см длиной), меньшим размером глазниц, скульптурой черепа. Глазницы направлены скорее вверх, чем в стороны. Вероятно, камакопс больше времени проводил в воде. Панцирный щиток американского рода Alegeinosaurus известен из местонахождения Усть-Коин в республике Коми. Он относится к нижнеказанскому веку (голюшерминский субкомплекс).

Большой исторический интерес представляет крупный диссорофид зигозавр (Zygosaurus lucius). Его череп был обнаружен майором фон Кваленом в 1847 году в Ключевском руднике в Оренбургской области. Род описан Эдуардом Эйхвальдом в 1848 году. Это одна из первых находок позвоночных в медистых песчаниках Приуралья. Череп зигозавра высокий, удлиненно-овальный, сильно скульптированный, длина черепа до 17 см (по Эйхвальду — «длина 4 вершка, ширина 3 вершка»). Череп резко сужается впереди глазниц, расширяется в височной области и вновь сужается к затылку. Огромное теменное отверстие. Крупные конические зубы.

По возрасту он принадлежит к ишеевскому комплексу — это последний из известных диссорофид. Кроме черепа, других костей этого темноспондила не обнаружено.

К диссорофидам принадлежит крайне необычное животное — платигистрикс (Platyhystrix rugosus). У этого диссорофида, достигавшего 70 см длины имелись необычно высокие скульптированные остистые отростки спинных позвонков. Концы этих выростов расширены и уплощены (наподобие хоккейной клюшки), покрыты бугорками. Вид описан Кейзом в 1910 году как пеликозавр Ctenosaurus rugosus (по остаткам позвонков, из-за сходства в строении с эдафозаврами), в особый род выделен Виллистоном в 1911 году. Остатки этого животного известны из позднекарбоновых — раннепермских (формация Або/Катлер) отложений Нью-Мексико и Техаса. Судя по всему, отростки образовывали «парус». В отличие от «паруса» пеликозавров, у платигистрикса на остистых отростках нет следов выраженной васкуляризации, поэтому его «парус» вряд ли служил для терморегуляции.

Диссорофиды часто рассматриваются как предки бесхвостых земноводных, но они были слишком специализированы. Больше сходны с возможными предками анур мелкие диссорофоиды — амфибамиды, бранхиозавриды, микрофолиды.

Диссорофиды (Dissorophidae) — семейство темноспондилов позднего карбона — перми. Наиболее наземные из всех темноспондилов. Скелет массивный, тело короткое, конечности длинные, сильные. Голова огромная относительно размеров тела. Череп высокий и широкий, огромные глазницы, крупное теменное отверстие. Огромные ушные вырезки, судя по строению окружающей кости, содержали барабанную перепонку. Затылочный мыщелок парный. Челюстное сочленение на уровне затылочного. Скульптура черепа гребнистая. Края орбит и теменного отверстия окружены костными валиками, что предполагает толстую кожу. У большинства известен дермальный панцирь на спине из парных рядов костных пластин, приросших к остистым отросткам позвонков, у какопса пластины лежали в два слоя (внутренний слой прирастал к позвонкам). Кожа, по-видимому, мягкая, следов чешуи не выявлено. Хвост короткий. Вероятно, прибрежные амфибиотические и полуназемные хищники. Есть свидетельства (следы зубов на костях), что крупные диссорофиды могли питаться и падалью.

Не менее 15 родов, из позднего карбона — средней перми Северного полушария. Большинство родов описано из ранней перми Северной Америки.

Наиболее известен род какопс (Cacops) с единственным видом C. aspidephorus, описанным Сэмюэлем Виллистоном в 1910 году из ранней перми (клир-форк) Техаса. Скелет часто изображают в литературе. Длина черепа около 20 см, общая длина до 50 см. Виллистон считал какопса ночным животным из-за очень крупных глазниц. Череп слегка удлинённый, высокий, сжатый с боков. Ноздри крупные, сближенные. Огромные ушные вырезки. Есть пре- и постхоанные небные клыки, наружная крыловидная кость без зубов. 21 предкрестцовый позвонок, 2 крестцовых, 21—22 хвостовых. Пластинки спинного панциря соединены друг с другом и с остистыми отростками, слегка шире позвонков.

Описанный в 1980 году Ю. М. Губиным камакопс (Kamacops acervalis) из средней перми Пермской области (очёрская фауна) — ближайший родственник какопса. От своего американского родича отличается более крупными размерами (череп до 25—30 см длиной), меньшим размером глазниц, скульптурой черепа. Глазницы направлены скорее вверх, чем в стороны. Вероятно, камакопс больше времени проводил в воде. Панцирный щиток американского рода Alegeinosaurus известен из местонахождения Усть-Коин в республике Коми. Он относится к нижнеказанскому веку (голюшерминский субкомплекс).

Большой исторический интерес представляет крупный диссорофид зигозавр (Zygosaurus lucius). Его череп был обнаружен майором фон Кваленом в 1847 году в Ключевском руднике в Оренбургской области. Род описан Эдуардом Эйхвальдом в 1848 году. Это одна из первых находок позвоночных в медистых песчаниках Приуралья. Череп зигозавра высокий, удлиненно-овальный, сильно скульптированный, длина черепа до 17 см (по Эйхвальду — «длина 4 вершка, ширина 3 вершка»). Череп резко сужается впереди глазниц, расширяется в височной области и вновь сужается к затылку. Огромное теменное отверстие. Крупные конические зубы.

По возрасту он принадлежит к ишеевскому комплексу — это последний из известных диссорофид. Кроме черепа, других костей этого темноспондила не обнаружено.

К диссорофидам принадлежит крайне необычное животное — платигистрикс (Platyhystrix rugosus). У этого диссорофида, достигавшего 70 см длины имелись необычно высокие скульптированные остистые отростки спинных позвонков. Концы этих выростов расширены и уплощены (наподобие хоккейной клюшки), покрыты бугорками. Вид описан Кейзом в 1910 году как пеликозавр Ctenosaurus rugosus (по остаткам позвонков, из-за сходства в строении с эдафозаврами), в особый род выделен Виллистоном в 1911 году. Остатки этого животного известны из позднекарбоновых — раннепермских (формация Або/Катлер) отложений Нью-Мексико и Техаса. Судя по всему, отростки образовывали «парус». В отличие от «паруса» пеликозавров, у платигистрикса на остистых отростках нет следов выраженной васкуляризации, поэтому его «парус» вряд ли служил для терморегуляции.

Диссорофиды часто рассматриваются как предки бесхвостых земноводных, но они были слишком специализированы. Больше сходны с возможными предками анур мелкие диссорофоиды — амфибамиды, бранхиозавриды, микрофолиды.

ディッソロフス科(学名:Dissorophidae)は、古生代石炭紀後期からペルム紀中期にかけて、ヨーロッパと北米に生息していた迷歯亜綱分椎目に属する絶滅両生類である。

非常に陸生傾向の強いグループで、強靭な脊椎、頑丈で短い胴、短い尾、長い四肢、大きく幅広く丈の高い頭部を有する。

背部に脊椎に沿って皮骨性の装甲板の列があり、重力へ対抗する構造物と外敵への防御の役割を果たしていた。

大きな耳切痕を持つ。十分細く振動を伝えることができる鐙骨が存在することから、鼓膜が張られ聴覚器官としての役割を果たしていたと思われる。一部の種では後端が閉じて孔状になっており、現生の無尾目と共通する構造になっている。そのことから、無尾目の祖先とする論者もいるが、それにしては特殊化しすぎているという反論も強い。

少なくとも15の属が知られている。そのうち多くはペルム紀前期の北米に生息していた。