pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

Triton (lat. Triturus), quyruqlular (Caudata) dəstəsindən suda-quruda yaşayanlar cinsi.

Triturus je rod obojživelníků patřící do čeledi mlokovití (Salamandridae). Původně čítal většinu čolků žijících v Evropě, některé rody, například Ichthyosaura, Lissotriton a Ommatotriton však byly odděleny a tak je rod Triturus složen z těchto druhů: Triturus anatolicus, Triturus carnifex (čolek dravý), Triturus cristatus (čolek velký), Triturus dobrogicus (čolek dunajský), Triturus ivanbureschi, Triturus karelinii (čolek balkánský), Triturus macedonicus, Triturus pygmaeus (čolek portugalský) a vyhynulého Triturus opalinus. Jednotlivé druhy navzájem mohou tvořit hybridy.

Členové rodu se vyskytují na území od Velké Británie, přes většinu kontinentální Evropy až k Sibiři, Anatolii a Kaspickému moři. Jedná se o velké druhy mloků, dosahují velikosti 10 až 16 cm, některé z nich i 20 cm. Velikost je závislá na pohlaví a životním prostředí. Zbarvení je tmavohnědé, s černými skvrnami na bocích, u některých druhů se vyskytují světlé tečky. Břicho je zbarveno žlutě až žlutooranžově s černými skvrnami. Během období rozmnožování hlavně samci čolků změní své zbarvení.

Čolci draví se vyvíjejí ve vodě jako larvy a pak se zde každoročně vracejí za účelem rozmnožování. U čolků dochází k vnějšímu oplození ve vejcovodu. Samice klade vajíčka na vodní rostliny a za dva až pět týdnů se z nich vylíhnou larvy. Dospělci se z nich stanou za dva až čtyři týdny.

Nebezpečí pro čolky představuje převážně ztráta přirozeného prostředí. Mezi přirozené nepřátele pak patří například vodní ptáci, dravé ryby, užovka obojková a různí savci.

V tomto článku byl použit překlad textu z článku Triturus na anglické Wikipedii.

Triturus je rod obojživelníků patřící do čeledi mlokovití (Salamandridae). Původně čítal většinu čolků žijících v Evropě, některé rody, například Ichthyosaura, Lissotriton a Ommatotriton však byly odděleny a tak je rod Triturus složen z těchto druhů: Triturus anatolicus, Triturus carnifex (čolek dravý), Triturus cristatus (čolek velký), Triturus dobrogicus (čolek dunajský), Triturus ivanbureschi, Triturus karelinii (čolek balkánský), Triturus macedonicus, Triturus pygmaeus (čolek portugalský) a vyhynulého Triturus opalinus. Jednotlivé druhy navzájem mohou tvořit hybridy.

Členové rodu se vyskytují na území od Velké Británie, přes většinu kontinentální Evropy až k Sibiři, Anatolii a Kaspickému moři. Jedná se o velké druhy mloků, dosahují velikosti 10 až 16 cm, některé z nich i 20 cm. Velikost je závislá na pohlaví a životním prostředí. Zbarvení je tmavohnědé, s černými skvrnami na bocích, u některých druhů se vyskytují světlé tečky. Břicho je zbarveno žlutě až žlutooranžově s černými skvrnami. Během období rozmnožování hlavně samci čolků změní své zbarvení.

Čolci draví se vyvíjejí ve vodě jako larvy a pak se zde každoročně vracejí za účelem rozmnožování. U čolků dochází k vnějšímu oplození ve vejcovodu. Samice klade vajíčka na vodní rostliny a za dva až pět týdnů se z nich vylíhnou larvy. Dospělci se z nich stanou za dva až čtyři týdny.

Nebezpečí pro čolky představuje převážně ztráta přirozeného prostředí. Mezi přirozené nepřátele pak patří například vodní ptáci, dravé ryby, užovka obojková a různí savci.

Triturus ist eine Gattung der Schwanzlurche aus der Familie der Echten Salamander und Molche (Salamandridae). Traditionell enthält sie ca. 15 Arten, darunter auch alle in Mitteleuropa heimischen Wassermolche. Infolge molekulargenetischer und morphologischer Verwandtschaftsanalysen werden nunmehr nur noch die Kammmolche und die beiden Arten der Marmormolche in die Gattung Triturus gestellt und die übrigen Arten werden drei separaten Gattungen zugewiesen.

Das Wort „Triturus“ ist zusammengesetzt aus zwei altgriechischen Wörtern:

„Triturus“ bedeutet demnach so viel wie geschwänzter Wassergott. Der Name wurde 1815 vom US-amerikanischen Biologen Constantine Samuel Rafinesque-Schmaltz eingeführt als Ersatz für den bis dahin gebräuchlichen, vom österreichischen Naturforscher Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti im Jahre 1768 geprägten Gattungsnamen Triton. Dieser wurde bereits 10 Jahre zuvor vom berühmten Carl von Linné an eine vermeintliche Weichtiergattung vergeben* und war deshalb für die Lurche nicht mehr frei.

Die Vertreter der Gattung Triturus verbringen einen Teil des Jahres an Land, suchen jedoch zumindest zur Fortpflanzung Gewässer auf. Dabei entwickeln die Männchen eine arttypische Wassertracht, die meist durch leuchtende Körperfarben und/oder einen flexiblen Hautkamm auf Rücken und Schwanz geprägt ist. Wassermolche zeigen ein charakteristisches Balzverhalten, bei dem das Männchen das weitgehend passive Weibchen umwirbt. Gewöhnlich befächelt dabei das Männchen mit seiner eingeschlagenen Schwanzspitze das Weibchen und versetzt ihm zwischendurch einen peitschenartigen Schlag. Schließlich setzt es ein Samenpaket, eine sogenannte Spermatophore, auf dem Grund ab, über die sich das Weibchen bewegt, um sie mit der Kloake aufzunehmen (indirekte innere Befruchtung). Es legt später die Eier in der Regel einzeln ab, wobei diese an Wasserpflanzen oder an am Gewässerboden liegende Blätter geheftet und dabei „eingewickelt“ werden.

Triturus

„Triturus“

vittatus (= Ommatotriton)

Mesotriton (= Ichthyosaura)

Lissotriton

Traditionell werden folgende Arten und Unterarten der Gattung Triturus zugerechnet (diese wissenschaftlichen Namen werden aber auch heute noch oft von taxonomisch eher konservativen Herpetologen verwendet; zzgl. neu abgegrenzter Taxa):

Schon mehrfach in der herpetologischen Geschichte hatte es Versuche gegeben, die Gattung Triturus taxonomisch weiter zu differenzieren. Naheliegend erscheint eine engere Verwandtschaft einerseits der kleinwüchsigen Arten wie Teichmolch, Fadenmolch oder Italienischer Wassermolch, andererseits der großen Kammmolche und Marmormolche. So schlug István József Bolkay 1928 vor die Gattung Triturus in drei Untergattungen namens Paleotriton, Mesotriton und Neotriton zu gliedern.

Im Jahr 2004 empfahl ein spanisches Autorenkollektiv aufgrund der Ergebnisse molekulargenetischer Verwandtschaftsanalysen die Klassifizierung der kleinwüchsigen Molche und des Bergmolches als jeweils eigenständige Gattungen, einhergehend mit einer Wiederbelebung der bereits im 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhundert geprägten Namen Lissotriton bzw. Mesotriton.[1]

Ein anderer Vorschlag erfolgte im Jahr 2005.[2] Auch dieser sieht die Stellung des Bergmolches in eine eigene Gattung Mesotriton vor und will die Kammmolch- und Marmormolch-Arten weiterhin in der Gattung Triturus belassen. Allerdings sollen die kleinen Molche nicht Lissotriton, sondern Lophinus heißen und zudem soll der Bandmolch als Ommatotriton in den Gattungsrang erhoben werden und seine beiden bisherigen Unterarten Artstatus erhalten – mit Ommatotriton vittatus als Name für die südliche und Ommatotriton ophryticus als Name für die nördliche Population.

Inzwischen (2009/2010) scheint sich bis auf weiteres eine Mischung aus diesen Vorschlägen durchgesetzt zu haben, wobei beim Bergmolch nach der Auswertung historischer Literatur nochmal eine Korrektur seines Gattungsnamens von Mesotriton auf das ältere und damit prioritäre Ichthyosaura gefordert wurde.[3]

Demnach verteilen sich die traditionellen Triturus-Arten nebst inzwischen neu beschriebener Taxa auf folgende Gattungen:

Triturus ist eine Gattung der Schwanzlurche aus der Familie der Echten Salamander und Molche (Salamandridae). Traditionell enthält sie ca. 15 Arten, darunter auch alle in Mitteleuropa heimischen Wassermolche. Infolge molekulargenetischer und morphologischer Verwandtschaftsanalysen werden nunmehr nur noch die Kammmolche und die beiden Arten der Marmormolche in die Gattung Triturus gestellt und die übrigen Arten werden drei separaten Gattungen zugewiesen.

Triton (vodenjak, mrmoljak) (Triturus) je rod repatih vodozemaca iz porodice daždevnjaka (Salamandridae). Vrste ovog roda imaju duguljasto tijelo sa slabim i kratkim nogama. Rep je lateralno spljošten i ima značajnu ulogu u plivanju. Imaju sposobnost regeneracije izgubljenih i oštećenih dijelova tijela kao što su noge, rep i oči. Tritoni su zaštićeni i široko rasprostranjeni u Bosni i Hercegovini. Historijski većina evropskih tritona (vodenjaka) je bila uključena u rod Triturus, međutim prema savremenoj klasifikaciji, taksonomi su ovaj rod podijelili u tri roda: Ichtyosaura (alpski tritoni), Lissotriton (mali tritoni) i Ommatotriton.[1]

Tritoni u proljeće borave u vodi (slatkovodne stajaćice - bare ili jezera). Kasnije izlaze na kopno, gdje i prezime u fazi zimskog mirovanja, skriveni pod kamenjem ili granjem. Široko su rasprostranjeni u Evropi.

Tritoni su grabežljivi, i hrane se puževima, glistama te larvama insekata. Doba parenja je u proljeće. Jaja polažu u vodu, na listove barskih biljaka. Njihove larve liče na punoglavce koji isprva nemaju noge, a kasnije izgledaju kao mali tritoni sa škrgama na bočnim stranama glave, koje nalikuju malim pramenovima perja. Metamorfoza larvi završava pretvaranjem škrga u pluća. U doba parenja, mužjacima nekih vrsta, duž leđa naraste greben, a kod većine vrsta donji dio tijela postane intenzivno narančaste do crvene boje. Neke vrste život provode u neotenom stadiju.

Vrste roda Triturus, prema novoj klasifikaciji, podijeljene su u rodove Ichtyosaura, Lissotriton i Ommatotriton.[2][3]

Ichtyosaura:

Lissotriton:

Ommatotriton:

Triton (vodenjak, mrmoljak) (Triturus) je rod repatih vodozemaca iz porodice daždevnjaka (Salamandridae). Vrste ovog roda imaju duguljasto tijelo sa slabim i kratkim nogama. Rep je lateralno spljošten i ima značajnu ulogu u plivanju. Imaju sposobnost regeneracije izgubljenih i oštećenih dijelova tijela kao što su noge, rep i oči. Tritoni su zaštićeni i široko rasprostranjeni u Bosni i Hercegovini. Historijski većina evropskih tritona (vodenjaka) je bila uključena u rod Triturus, međutim prema savremenoj klasifikaciji, taksonomi su ovaj rod podijelili u tri roda: Ichtyosaura (alpski tritoni), Lissotriton (mali tritoni) i Ommatotriton.

Lu trituni è n'anfibbiu nicu dû gèniri Triturus o dû gèniri Euproctus.

Triturus is e geslacht van salamanders uut de familie van d' echte salamanders (Salamandridae).

Der zyn teegnwoordig acht soort'n, die allemolle leevn in grôte dêeln van Europa. 't Zyn typische amfibien; in de lente en e dêel van de zomer leevn z' in 't woater. De reste van 't joar kruup'n z' over 't land en zien ze der anders uut, klinder, dounkerder, e ruw vel en gin zichtboare rikkam.

Triturus ye un chenero d'amfibios urodelos en a familia Salamandridae, subfamilia Pleurodelinae. A suya aria de destribución se troba en Europa, y seguntes a suya clasificación scientifica en fan parte siet especies, que se citan contino:

Triturus is e geslacht van salamanders uut de familie van d' echte salamanders (Salamandridae).

Der zyn teegnwoordig acht soort'n, die allemolle leevn in grôte dêeln van Europa. 't Zyn typische amfibien; in de lente en e dêel van de zomer leevn z' in 't woater. De reste van 't joar kruup'n z' over 't land en zien ze der anders uut, klinder, dounkerder, e ruw vel en gin zichtboare rikkam.

Triturus ye un chenero d'amfibios urodelos en a familia Salamandridae, subfamilia Pleurodelinae. A suya aria de destribución se troba en Europa, y seguntes a suya clasificación scientifica en fan parte siet especies, que se citan contino:

Triturus carnifex (Laurenti, 1768). Triturus cristatus (Laurenti, 1768). Triturus dobrogicus (Kiritzescu, 1903). Triturus karelinii (Strauch, 1870). Triturus macedonicus (Karaman, 1922). Triturus marmoratus (Latreille, 1800). Triturus pygmaeus (Wolterstorff, 1905).Οι χτενοτρίτωνες αποτελούν μια ομάδα μεγάλου μεγέθους τριτώνων του γένους Triturus στην οικογένεια Salamandridae. Έξι είδη απαντώνται στην Ευρώπη, δύο από τα οποία εντοπίζονται και στην Ελλάδα[1]: Ο Βαλκανικός χτενοτρίτωνας, Triturus ivanbureschi Arntzen & Wielstra, 2013[2] και ο Μακεδονικός χτενοτρίτωνας, Triturus macedonicus (Karaman, 1922)[3].

Οι χτενοτρίτωνες αποτελούν μια ομάδα μεγάλου μεγέθους τριτώνων του γένους Triturus στην οικογένεια Salamandridae. Έξι είδη απαντώνται στην Ευρώπη, δύο από τα οποία εντοπίζονται και στην Ελλάδα: Ο Βαλκανικός χτενοτρίτωνας, Triturus ivanbureschi Arntzen & Wielstra, 2013 και ο Μακεδονικός χτενοτρίτωνας, Triturus macedonicus (Karaman, 1922).

Мрморец или тритон (лат. Triturus) — род од редот опашестите водоземци (Caudata; Urodela), кои се помали од дождовниците (Salamandra). Во времето на парењето, мажјакот развива кожен набор на грбната страна, кој може да помине и на опашката, по што јасно се разликува од женката. Некои видови живеат постојано во вода, а други само при парењето и полагањето на јајца, а потоа се повлекуваат на копно, каде што и презимуваат.

Кај нас живеат 4 видови мрморци, и тоа се:

Македонска Енциклопедија. Скопје, Македонија: Македонска академија на науките и уметностите. 2009. стр. 1511. ISBN 978-608-203-023-4.

Мрморец или тритон (лат. Triturus) — род од редот опашестите водоземци (Caudata; Urodela), кои се помали од дождовниците (Salamandra). Во времето на парењето, мажјакот развива кожен набор на грбната страна, кој може да помине и на опашката, по што јасно се разликува од женката. Некои видови живеат постојано во вода, а други само при парењето и полагањето на јајца, а потоа се повлекуваат на копно, каде што и презимуваат.

Кај нас живеат 4 видови мрморци, и тоа се:

планински мрморец (Triturus alpestris), македонски мрморец (Triturus carnifex macedonicus), балкански мрморец (Triturus karelinii) и мал мрморец (Triturus vulgaris)Тритондор, сайгычтуулар (Triturus) - куйруктуу жерде-сууда жашоочулардын саламандралар тукумундагы уруусу.

Денесинин уз. 18 эмче. Куйругу капталынан кысыңкы. Тритондордун 10 түрү Европада, Азиянын Европага чектеш жагында кездешет. Түздүктө, тоодо, көбүнчө токойдо жашайт. Кургакта негизинен кемирүүчүлөрдүн ийининде, чириндилердин астында кыштайт. Жазында жумурткасын таштоо жана уруктануу үчүн көлмөлөргө келет. Личинкасы 3-5 айдан кийин, кээде кийинки жылы Тритондорго айланат. Тритондор майда рак сымалдар, моллюскалар, суу курт-кумурскасы, сөөлжан, чымын-чиркей ж. б. менен азыктанат. Лабораторияда пайдаланылат

Кыргыз Совет Энциклопедиясы. Башкы редактор Б. О. Орузбаева. -Фрунзе: Кыргыз Совет Энциклопедиясынын башкы редакциясы, 1980. Т. 6. Тоо климаты - Яшма. -656 б.

Тритондор, сайгычтуулар (Triturus) - куйруктуу жерде-сууда жашоочулардын саламандралар тукумундагы уруусу.

Денесинин уз. 18 эмче. Куйругу капталынан кысыңкы. Тритондордун 10 түрү Европада, Азиянын Европага чектеш жагында кездешет. Түздүктө, тоодо, көбүнчө токойдо жашайт. Кургакта негизинен кемирүүчүлөрдүн ийининде, чириндилердин астында кыштайт. Жазында жумурткасын таштоо жана уруктануу үчүн көлмөлөргө келет. Личинкасы 3-5 айдан кийин, кээде кийинки жылы Тритондорго айланат. Тритондор майда рак сымалдар, моллюскалар, суу курт-кумурскасы, сөөлжан, чымын-чиркей ж. б. менен азыктанат. Лабораторияда пайдаланылат

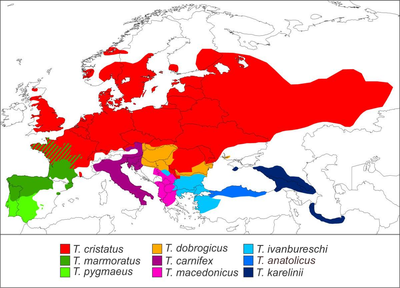

Triturus is a genus of newts comprising the crested and the marbled newts, which are found from Great Britain through most of continental Europe to westernmost Siberia, Anatolia, and the Caspian Sea region. Their English names refer to their appearance: marbled newts have a green–black colour pattern, while the males of crested newts, which are dark brown with a yellow or orange underside, develop a conspicuous jagged seam on their back and tail during their breeding phase.

Crested and marbled newts live and breed in vegetation-rich ponds or similar aquatic habitats for two to six months and usually spend the rest of the year in shady, protection-rich land habitats close to their breeding sites. Males court females with a ritualised display, ending in the deposition of a spermatophore that is picked up by the female. After fertilisation, a female lays 200–400 eggs, folding them individually into leaves of water plants. Larvae develop over two to four months before metamorphosing into land-dwelling juveniles.

Historically, most European newts were included in the genus, but taxonomists have split off the alpine newts (Ichthyosaura), the small-bodied newts (Lissotriton) and the banded newts (Ommatotriton) as separate genera. The closest relatives of Triturus are the European brook newts (Calotriton). Two species of marbled newts and seven species of crested newts are accepted, of which the Anatolian crested newt was only described in 2016. Their ranges are largely contiguous but where they do overlap, hybridisation may take place.

Although not immediately threatened, crested and marbled newts suffer from population declines caused mainly by habitat loss and fragmentation. Both their aquatic breeding sites and the cover-rich, natural landscapes upon which they depend during their terrestrial phase are affected. All species are legally protected in Europe, and some of their habitats have been designated as special reserves.

The genus name Triturus was introduced in 1815 by the polymath Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, with the northern crested newt (Triturus cristatus) as type species.[2] That species was originally described as Triton cristatus by Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti in 1768, but Linnaeus had already used the name Triton for a genus of sea snails ten years before, making a new genus name for the newts necessary.[3][5]

Triturus included most European newt species until the end of the 20th century, but was substantially revised after it was shown to be polyphyletic.[3] Three separate genera now accommodate former members of the genus: the small-bodied newts (Lissotriton), the banded newts (Ommatotriton), and the alpine newt (Ichthyosaura). The monophyly of the genus Triturus in the strict sense is supported by molecular data[1] and synapomorphies such as a genetic defect causing 50% embryo mortality (see below, Egg deposition and development).

As of 2020, the genus contains seven species of crested newts and two species of marbled newts.[3][6] Both groups were long considered as single species, Triturus cristatus and T. marmoratus, respectively. Substantial genetic differences between subspecies were, however, noted and eventually led to their recognition as full species, with the crested newts often collectively referred to as "T. cristatus superspecies".[3] The Balkan and the Anatolian crested newt, the most recent species formally described (2013 and 2016, respectively), were only recognised through genetic data; together with the Southern crested newt, they form a cryptic species complex with no morphological differences known.[7][4]

Triturus is a genus of rather large-bodied newts. They typically have a total length of between 10 and 16 cm (3.9 and 6.3 in), with some crested newts of up to 20 cm (8 in) described. Size depends on sex and the environment: females are slightly larger and have a proportionally longer tail than males in most species, and the Italian crested newt seems to be larger in colder parts of its range.[8]: 12–15 [9]: 142–147

Crested newts are dark brown, with black spots on the sides, and white stippling in some species. Their belly is yellow to orange with black blotches, forming a pattern characteristic for individuals. Females and juveniles of some species have a yellow line running down their back and tail. During breeding phase, crested newts change in appearance, most markedly the males. These develop a skin seam running along their back and tail; this crest is the namesake feature of the crested newts and can be up to 1.5 cm high and very jagged in the northern crested newt. Another feature of males at breeding time is a silvery-white band along the sides of the tail.[8]: 12–15 [9]: 142–147

Marbled newts owe their name to their green–black, marbled colour pattern. In females, an orange-red line runs down back and tail. The crest of male marbled newts is smaller and fleshier than that of the crested newts and not indented, but marbled newt males also have a whitish tail band at breeding time.[9]: 142–147

Apart from the obvious colour differences between crested and marbled newts, species in the genus also have different body forms. They range from stocky with sturdy limbs in the Anatolian, Balkan and the southern crested newt as well as the marbled newts, to very slender with short legs in the Danube crested newt.[7] These types were first noted by herpetologist Willy Wolterstorff, who used the ratio of forelimb length to distance between fore- and hindlimbs to distinguish subspecies of the crested newt (now full species); this index however sometimes leads to misidentifications.[8]: 10 The number of rib-bearing vertebrae in the skeleton was shown to be a better species indicator. It ranges from 12 in the marbled newts to 16–17 in the Danube crested newt and is usually observed through radiography on dead or sedated specimens.[10][11]

The two marbled newts are readily distinguished by size and colouration.[12] In contrast, separating crested newt species based on appearance is not straightforward, but most can be determined by a combination of body form, coloration, and male crest shape.[8]: 10–15 The Anatolian, Balkan, and southern crested newt however are cryptic, morphologically indistinguishable species.[4] Triturus newts occupy distinct geographical regions (see Distribution), but hybrid forms occur at range borders between some species and have intermediate characteristics (see Hybridisation and introgression).

Based on the books of Griffiths (1996)[9] and Jehle et al. (2011),[8] with additions from articles on recently recognised species.[4][7][12] NRBV = number of rib-bearing vertebrae, values from Wielstra & Arntzen (2011).[10] Triturus anatolicus, T. ivanbureschi and T. karelinii are cryptic species and have only been separated through genetic analysis.[7][4]

Like other newts, Triturus species develop in the water as larvae, and return to it each year for breeding. Adults spend one half to three quarters of the year on land, depending on the species, and thus depend on both suitable aquatic breeding sites and terrestrial habitats. After larval development in the first year, juveniles pass another year or two before reaching maturity; in the north and at higher elevations, this can take longer. The larval and juvenile stages are the riskiest for the newts, while survival is higher in adults. Once the risky stages passed, adult newts usually attain an age of seven to nine years, although individuals of the northern crested newts have reached 17 years in the wild.[8]: 98–99

The aquatic habitats preferred by the newts are stagnant, mid- to large-sized, unshaded water bodies with abundant underwater vegetation but without fish, which prey on larvae. Typical examples are larger ponds, which need not be of natural origin; indeed, most ponds inhabited by the northern crested newt in the UK are human-made.[8]: 48 Examples of other suitable secondary habitats are ditches, channels, gravel pit lakes, garden ponds, or (in the Italian crested newt) rice paddies. The Danube crested newt is more adapted to flowing water and often breeds in river margins, oxbow lakes or flooded marshland, where it frequently co-occurs with fish. Other newts that can be found in syntopy with Triturus species include the smooth, the palmate, the Carpathian, and the alpine newt.[8]: 44–48 [9]: 142–147 [13]

Adult newts begin moving to their breeding sites in spring when temperatures stay above 4–5 °C (39–41 °F). This usually occurs in March for most species, but can be much earlier in the southern parts of the distribution range. Southern marbled newts mainly breed from January to early March and may already enter ponds in autumn.[14] The time adults spend in water differs among species and correlates with body shape: while it is only about three months in the marbled newts, it is six months in the Danube crested newt, whose slender body is best adapted to swimming.[8]: 44 Triturus newts in their aquatic phase are mostly nocturnal and, compared to the smaller newts of Lissotriton and Ichthyosaura, usually prefer the deeper parts of a water body, where they hide under vegetation. As with other newts, they occasionally have to move to the surface to breathe air. The aquatic phase serves not only for reproduction, but also offers the animals more abundant prey, and immature crested newts frequently return to the water in spring even if they do not breed.[8]: 52–58 [9]: 142–147

During their terrestrial phase, crested and marbled newts depend on a landscape that offers cover, invertebrate prey and humidity. The precise requirements of most species are still poorly known, as the newts are much more difficult to detect and observe on land. Deciduous woodlands or groves are in general preferred, but conifer woods are also accepted, especially in the far northern and southern ranges. The southern marbled newt is typically found in Mediterranean oak forests.[15] In the absence of forests, other cover-rich habitats, as for example hedgerows, scrub, swampy meadows, or quarries, can be inhabited. Within such habitats, the newts use hiding places such as logs, bark, planks, stone walls, or small mammal burrows; several individuals may occupy such refuges at the same time. Since the newts in general stay very close to their aquatic breeding sites, the quality of the surrounding terrestrial habitat largely determines whether an otherwise suitable water body will be colonised.[8]: 47–48, 76 [13][16]

Juveniles often disperse to new breeding sites, while the adults in general move back to the same breeding sites each year. The newts do not migrate very far: they may cover around 100 metres (110 yd) in one night and rarely disperse much farther than one kilometre (0.62 mi). For orientation, the newts likely use a combination of cues including odour and the calls of other amphibians, and orientation by the night sky has been demonstrated in the marbled newt.[17] Activity is highest on wet nights; the newts usually stay hidden during daytime. There is often an increase in activity in late summer and autumn, when the newts likely move closer to their breeding sites. Over most of their range, they hibernate in winter, using mainly subterranean hiding places, where many individuals will often congregate. In their southern range, they may instead sometimes aestivate during the dry months of summer.[8]: 73–78 [13]

Like other newts, Triturus species are carnivorous and feed mainly on invertebrates. During the land phase, prey include earthworms and other annelids, different insects, woodlice, and snails and slugs. During the breeding season, they prey on various aquatic invertebrates, and also tadpoles of other amphibians such as the common frog or common toad, and smaller newts.[8]: 58–59 Larvae, depending on their size, eat small invertebrates and tadpoles, and also smaller larvae of their own species.[13]

The larvae are themselves eaten by various animals such as carnivorous invertebrates and water birds, and are especially vulnerable to predatory fish.[13] Adults generally avoid predators through their hidden lifestyle but are sometimes eaten by herons and other birds, snakes such as the grass snake, and mammals such as shrews, badgers and hedgehogs.[8]: 78 They secrete the poison tetrodotoxin from their skin, albeit much less than for example the North American Pacific newts (Taricha).[18] The bright yellow or orange underside of crested newts is a warning coloration which can be presented in case of perceived danger. In such a posture, the newts typically roll up and secrete a milky substance.[8]: 79

A complex courting ritual performed underwater characterises the crested and marbled newts. Males are territorial and use leks, or courtship arenas, small patches of clear ground where they display and attract females. When they encounter other males, they use the same postures as described below for courting to impress their counterpart. Occasionally, they even bite each other; marbled newts seem more aggressive than crested newts. Males also frequently disturb the courting of other males and try to guide the female away from their rival. Pheromones are used to attract females, and once a male has found one he will pursue her and position himself in front of her. After this first orientation phase, courtship proceeds with display and spermatophore transfer.[8]: 80–89 [9]: 58–63

Courtship display serves to emphasise the male's body and crest size and to waft pheromones towards the female. A position characteristic for the large Triturus species is the "cat buckle", where the male's body is kinked and often rests only on the forelegs ("hand stand"). He will also lean towards the female ("lean-in"), rock his body, and flap his tail towards her, sometimes lashing it violently ("whiplash"). If the female shows interest, the ritual enters the third phase, where the male creeps away from her, his tail quivering. When the female touches his tail with her snout, he deposits a packet of sperm (a spermatophore) on the ground. The ritual ends with the male guiding the female over the spermatophore, which she then takes up with her cloaca. In the southern marbled newt, courtship is somewhat different from the larger species in that it does not seem to involve male "cat buckles" and "whiplashes", but instead slower tail fanning and undulating of the tail tip (presumably to mimic a prey animal and lure the female).[8]: 80–89 [9]: 58–63 [14]

Females usually engage with several males over a breeding season. The eggs are fertilised internally in the oviduct. The female deposits them individually on leaves of aquatic plants, such as water cress or floating sweetgrass, usually close to the surface, and, using her hindlegs, folds the leaf around the eggs as protection from predators and radiation. In the absence of suitable plants, the eggs may also be deposited on leaf litter, stones, or even plastic bags. In the northern crested newt, a female takes around five minutes for the deposition of one egg. Crested newt females usually lay around 200 eggs per season, while the marbled newt (T. marmoratus) can lay up to 400. Triturus embryos are usually light-coloured, 1.8–2 mm in diameter with a 6 mm jelly capsule, which distinguishes them from eggs of other co-existing newt species that are smaller and darker-coloured. A genetic particularity in the genus causes 50% of the embryos to die: their development is arrested when they do not possess two different variants of chromosome 1 (i.e., when they are homozygous for that chromosome).[8]: 61–62 [9]: 62–63, 147 [19][6]

Larvae hatch after two to five weeks, depending largely on temperature. In the first days after hatching, they live on their remaining embryonic yolk supply and are not able to swim, but attach to plants or the egg capsule with two balancers, adhesive organs on their head. After this period, they begin to ingest small invertebrates, and actively forage about ten days after hatching. As in all salamanders and newts, forelimbs—already present as stumps at hatching—develop first, followed later by the back legs. Unlike smaller newts, Triturus larvae are mostly nektonic, swimming freely in the water column. Just before the transition to land, the larvae resorb their external gills; they can at this stage reach a size of 7 centimetres (2.8 in) in the larger species. Metamorphosis takes place two to four months after hatching, but the duration of all stages of larval development varies with temperature. Survival of larvae from hatching to metamorphosis has been estimated at a mean of roughly 4% for the northern crested newt, which is comparable to other newts. In unfavourable conditions, larvae may delay their development and overwinter in water, although this seems to be less common than in the small-bodied newts. Paedomophic adults, retaining their gills and staying aquatic, have occasionally been observed in several crested newt species.[8]: 64–71 [9]: 73–74, 144–147

Crested and marbled newts are found in Eurasia, from Great Britain and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to West Siberia and the southern Caspian Sea region in the east, and reach north to central Fennoscandia. Overall, the species have contiguous, parapatric ranges; only the northern crested newt and the marbled newt occur sympatrically in western France, and the southern crested newt has a disjunct, allopatric distribution in Crimea, the Caucasus, and south of the Caspian Sea.[7]

The northern crested newt is the most widespread species, while the others are confined to smaller regions, e.g. the southwestern Iberian Peninsula in the southern marbled newt,[15] and the Danube basin and some of its tributaries in the Danube crested newt.[20] The Italian crested newt (T. carnifex) has been introduced outside its native range in some European countries and the Azores.[21] In the northern Balkans, four species of crested newt occur in close vicinity, and may sometimes even co-exist.[8]: 11

Triturus species usually live at low elevation; the Danube crested newt for example is confined to lowlands up to 300 m (980 ft) above sea level.[20] However, they do occur at higher altitudes towards the south of their range: the Italian crested newt is found up to 1,800 m (5,900 ft) in the Apennine Mountains,[22] the southern crested newt up to 2,000 m (6,600 ft) in the southern Caucasus,[22] and the marbled newt up to around 2,100 m (6,900 ft) in central Spain.[23]

The closest relatives of the crested and marbled newts are the European brook newts (Calotriton).[1][25] Phylogenomic analyses resolved the relationships within the genus Triturus: The crested and the marbled newts are sister groups, and within the crested newts, the Balkan–Asian group with T. anatolicus, T. karelinii and T. ivanbureschi is sister to the remaining species. The northern (T. cristatus) and the Danube crested newt (T. dobrogicus), as well as the Italian (T. carnifex) and the Macedonian crested newt (T. macedonicus), respectively, are sister species.[10][24] These relationships suggest evolution from a stocky build and mainly terrestrial lifestyle, as today found in the marbled newts, to a slender body and a more aquatic lifestyle, as in the Danube crested newt.[24]

A 24-million-year-old fossil belonging to Triturus, perhaps a marbled newt, shows that the genus already existed at that time.[1] A molecular clock study based on this and other fossils places the divergence between Triturus from Calotriton at around 39 mya in the Eocene, with an uncertainty range of 47 to 34 mya.[1] Based on this estimation, authors have investigated diversification within the genus and related it to paleogeography: The crested and marbled newts split between 30 and 24 mya, and the two species of marbled newts have been separated for 4.7–6.8 million years.[10]

The crested newts are believed to have originated in the Balkans[26] and radiated in a brief time interval between 11.5 and 8 mya: First, the Balkan–Asian group (the Anatolian, Balkan and southern crested newt) branched off from the other crested newts, probably in a vicariance event caused by the separation of the Balkan and Anatolian land masses. The origin of current-day species is not fully understood so far, but one hypothesis suggests that ecological differences, notably in the adaptation to an aquatic lifestyle, may have evolved between populations and led to parapatric speciation.[10][27] Alternatively, the complex geological history of the Balkan peninsula may have further separated populations there, with subsequent allopatric speciation and the spread of species into their current ranges.[26]

At the onset of the Quaternary glacial cycles, around 2.6 mya, the extant Triturus species had already emerged.[10] They were thus affected by the cycles of expansion and retreat of cold, inhospitable regions, which shaped their distribution. A study using environmental niche modelling and phylogeography showed that during the Last Glacial Maximum, around 21,000 years ago, crested and marbled newts likely survived in warmer refugia mainly in southern Europe. From there, they recolonised the northern parts after glacial retreat. The study also showed that species range boundaries shifted, with some species replacing others during recolonisation, for example the southern marbled newt which expanded northwards and replaced the marbled newt. Today's most widespread species, the northern crested newt, was likely confined to a small refugial region in the Carpathians during the last glaciation, and from there expanded its range north-, east- and westwards when the climate rewarmed.[27][28]

The northern crested newt and the marbled newt are the only species in the genus with a considerable range overlap (in western France). In that area, they have patchy, mosaic-like distributions and in general prefer different habitats.[23][29] When they do occur in the same breeding ponds, they can form hybrids, which have intermediate characteristics. Individuals resulting from the cross of a crested newt male with a marbled newt female had mistakenly been described as distinct species Triton blasii de l'Isle 1862, and the reverse hybrids as Triton trouessarti Peracca 1886. The first type is much rarer due to increased mortality of the larvae and consists only of males, while in the second, males have lower survival rates than females. Overall, viability is reduced in these hybrids and they rarely backcross with their parent species. Hybrids made up 3–7% of the adult populations in different studies.[30]

Other Triturus species only meet at narrow zones on their range borders. Hybridisation does occur in several of these contact zones, as shown by genetic data and intermediate forms, but is rare, supporting overall reproductive isolation. Backcrossing and introgression do however occur as shown by mitochondrial DNA analysis.[31] In a case study in the Netherlands, genes of the introduced Italian crested newt were found to introgress into the gene pool of the native northern crested newt.[32] The two marbled newt species can be found in proximity in a narrow area in central Portugal and Spain, but they usually breed in separate ponds, and individuals in that area could be clearly identified as one of the two species.[12][33] Nevertheless, there is introgression, occurring in both directions at some parts of the contact zone, and only in the direction of the southern marbled newt where that species had historically replaced the marbled newt[34] (see also above, Glacial refugia and recolonisation).

Most of the crested and marbled newts are listed as species of "least concern" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, but population declines have been registered in all assessed species.[21][35][36][37] The Danube crested newt and the southern marbled newt are considered "near threatened" because populations have declined significantly.[15][20] Populations have been affected more heavily in some countries and species are listed in some national red lists.[13] The Anatolian, Balkan and the Macedonian crested newt, recognised only recently, have not yet been evaluated separately for conservation status.[38]

The major threat for crested and marbled newts is habitat loss. This concerns especially breeding sites, which are lost through the upscaling and intensification of agriculture, drainage, urban sprawl, and artificial flooding regimes (affecting in particular the Danube crested newt). Especially in the southern ranges, exploitation of groundwater and decreasing spring rain, possibly caused by global warming, threaten breeding ponds. Aquatic habitats are also degraded through pollution with agricultural pesticides and fertiliser. Introduction of crayfish and predatory fish threatens larval development; the Chinese sleeper has been a major concern in Eastern Europe. Exotic plants can also degrade habitats: the swamp stonecrop replaces natural vegetation and overshadows waterbodies in the United Kingdom, and its hard leaves are unsuitable for egg-laying to crested newts.[9]: 106–110 [13]

Land habitats, equally important for newt populations, are lost through the replacement of natural forests by plantations or clear-cutting (especially in the northern range), and the conversion of structure-rich landscapes into uniform farmland. Their limited dispersal makes the newts especially vulnerable to fragmentation, i.e. the loss of connections for exchange between suitable habitats.[9]: 106–110 [13] High concentrations of road salt have been found to be lethal to crested newts.[39]

Other threats include illegal collection for pet trade, which concerns mainly the southern crested newt, and the northern crested newt in its eastern range.[13][36] The possibility of hybridisation, especially in the crested newts, means that native species can be genetically polluted through the introduction of close species, as it is the case with the Italian crested newt introduced in the range of the northern crested newt.[32] Warmer and wetter winters due to global warming may increase newt mortality by disturbing their hibernation and forcing them to expend more energy.[8]: 110 Finally, the genus is potentially susceptible to the highly pathogenic fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans, introduced to Europe from Asia.[40]

The crested newts are listed in Berne Convention Appendix II as "strictly protected", and the marbled newts in Appendix III as "protected".[41] They are also included in Annex II (species requiring designation of special areas of conservation; crested newts) and IV (species in need of strict protection; all species) of the EU habitats and species directive.[42] As required by these frameworks, their capture, disturbance, killing or trade, as well as the destruction of their habitats, are prohibited in most European countries.[41][42] The EU habitats directive is also the basis for the Natura 2000 protected areas, several of which have been designated for the crested newts.[13]

Habitat protection and management is seen as the most important element for the conservation of Triturus newts. This includes preservation of natural water bodies, reduction of fertiliser and pesticide use, control or eradication of introduced predatory fish, and the connection of habitats through sufficiently wide corridors of uncultivated land. A network of aquatic habitats in proximity is important to sustain populations, and the creation of new breeding ponds is in general very effective as they are rapidly colonised when other habitats are nearby. In some cases, entire populations have been moved when threatened by development projects, but such translocations need to be carefully planned to be successful.[8]: 118–133 [9]: 113–120 [13] Strict protection of the northern crested newt in the United Kingdom has created conflicts with local development projects; at the same time, the charismatic crested newts are seen as flagship species, whose conservation also benefits a range of other amphibians.[13]

Triturus is a genus of newts comprising the crested and the marbled newts, which are found from Great Britain through most of continental Europe to westernmost Siberia, Anatolia, and the Caspian Sea region. Their English names refer to their appearance: marbled newts have a green–black colour pattern, while the males of crested newts, which are dark brown with a yellow or orange underside, develop a conspicuous jagged seam on their back and tail during their breeding phase.

Crested and marbled newts live and breed in vegetation-rich ponds or similar aquatic habitats for two to six months and usually spend the rest of the year in shady, protection-rich land habitats close to their breeding sites. Males court females with a ritualised display, ending in the deposition of a spermatophore that is picked up by the female. After fertilisation, a female lays 200–400 eggs, folding them individually into leaves of water plants. Larvae develop over two to four months before metamorphosing into land-dwelling juveniles.

Historically, most European newts were included in the genus, but taxonomists have split off the alpine newts (Ichthyosaura), the small-bodied newts (Lissotriton) and the banded newts (Ommatotriton) as separate genera. The closest relatives of Triturus are the European brook newts (Calotriton). Two species of marbled newts and seven species of crested newts are accepted, of which the Anatolian crested newt was only described in 2016. Their ranges are largely contiguous but where they do overlap, hybridisation may take place.

Although not immediately threatened, crested and marbled newts suffer from population declines caused mainly by habitat loss and fragmentation. Both their aquatic breeding sites and the cover-rich, natural landscapes upon which they depend during their terrestrial phase are affected. All species are legally protected in Europe, and some of their habitats have been designated as special reserves.

Trituro (science:Triturus)[1] estas genro de amfibioj el la ordo de urodeloj, familio de salamandredoj, kun 5 fingroj sur ĉiu piedo kaj kun flanke plata vosto, ofte vivantaj en akvo.

Tiu genro uzis kiel indikospecio ĉar lia ĉeesto aŭ foresto povas indiki la sanon de la medio, ekz la pH de akvo aŭ iom poluadoj.

Tiuj amfibioj havas longan maldikan korpon, mallongajn krurojn, sen interfingrajn membranojn kaj bone evoluinta flanke platigita vosto. Ĝenerale, la trituroj estas pli malgrandaj ol salamandroj kaj plejparto de lia vivo estas en la akvo. Estas iom miopa en la akvo kaj havas tre klaran miopecon en tero.[2]

Havas larĝajn kaj platajn kraniojn, kun kunfanditajn parietalojn kaj provizita kun kurbigitaj dentoj en ambaŭ makzeloj. Ilia pelvo zono estas pliparte kartilaga. Kontraste ranoj, trituroj havas neniun meza orelo.[3]

Familio veraj salamandroj (Salamandridae); brankoj ekzistas nur en la larva stadio, ĉe la plenkreskaj bestoj mankas. Ili havas lacertosimilan korpon kaj 4 mallongajn, malfortajn krurojn. Jen kelkaj specioj:

Trituro (science:Triturus) estas genro de amfibioj el la ordo de urodeloj, familio de salamandredoj, kun 5 fingroj sur ĉiu piedo kaj kun flanke plata vosto, ofte vivantaj en akvo.

Tiu genro uzis kiel indikospecio ĉar lia ĉeesto aŭ foresto povas indiki la sanon de la medio, ekz la pH de akvo aŭ iom poluadoj.

Triturus es un género de anfibios caudados de la familia Salamandridae, compuesto por una serie de especies de Europa y Asia que se encuentran en cuerpos de agua, como estanques poco profundos, lagunas, arroyos y aguas profundas tranquilas; y terrestres, como páramos, pantanos y bosques.

Este género se ha usado como especie indicadora debido a que su presencia o ausencia puede indicar la salud del ambiente, por ejemplo el pH del agua y otros contaminantes.

Es considerado por la IUCN como una especie de preocupación menor; sin embargo, las poblaciones de las distintas especies han ido decreciendo y en otras se encuentran estables.[cita requerida]

Son animales bilaterales, triploblásticos, celomados y con dimorfismo sexual. Estos anfibios tienen un cuerpo largo y delgado, patas cortas, sin membranas interdigitales y una cola bien desarrollada y aplanada lateralmente. En general, los tritones son más pequeños que las salamandras y la mayor parte de su vida están en el agua. Son ligeramente miopes en el agua y tienen una miopía muy pronunciada en tierra. Poseen cráneos anchos y planos dorso-ventralmente con huesos parietales fusionados y provistos de dientes curvados en ambas mandíbulas. Presentan una cintura pélvica, en su mayor parte cartilaginosa, careciendo de una cintura escapular dérmica. A diferencia de las ranas, los tritones no tienen oído medio.

Hibernan enterrados en el lodo, debajo de hojas, de piedras o en el suelo y sufren modificaciones fisiológicas como la baja producción de glóbulos rojos y blancos durante este periodo. Además, los glóbulos aparecen agrupados en la zona submesotelial del hígado, decrece el número de eosinófilos y aumenta la proliferación de células pigmentadas en áreas parenquimal y hematopoyética, posiblemente para protegerlas de sustancias citotóxicas durante la inactividad del hígado. Cuando llega la primavera, si los individuos son adultos sexualmente maduros, empieza el cortejo (los machos tienen colores más vivos y llamativos que las hembras) y reproducción en los cuerpos de agua. Las larvas tienen branquias de apéndices ramificados que abarcan una gran superficie. Cuando son adultos su respiración es pulmonar y cutánea.

Los adultos producen toxinas que son secretadas por la piel como mecanismo de defensa contra depredadores naturales, como culebras; la toxina solo tiene efecto si se ingiere y no cuando se tiene contacto con el animal. Las larvas presentan una mayor tasa de depredadores, por ejemplo larvas de ranas, larvas de insectos, ditíscicos adultos y tritones adultos.

Tienen la capacidad de regenerar el eje principal del cuerpo principal y estructuras, como los ojos, la cola y las extremidades, perdidas en enfrentamientos con otros tritones, escapando del depredador o en algún accidente.

En su estadio de larva, los tritones tienen una dieta más limitada que los adultos, siendo ambos estadios carnívoros; sin embargo, el desarrollo de dientes en esta etapa hace que pueda alimentarse de larvas de urodelos e invertebrados, entre estos tenemos a rotíferos, zooplancton, moluscos, ácaros y larvas de otros insectos. El adulto se alimenta de invertebrados acuáticos, como gasterópodos, bivalvos, crustáceos, nematodos, anélidos y larvas de insectos, y de invertebrados terrestres,como arácnidos, crustáceos, ciempiés, insectos, larvas, huevos y adultos de algunos anfibios.

Es posible encontrar las larvas en estanques poco profundos, lagunas, arroyos y aguas profundas tranquilas. Los adultos son principalmente nocturnos, pero pueden tener actividad diurna si viven adyacentes a un cuerpo de agua o la humedad relativa ambiental es alta. En tierra, se han observado en bosques caducidófilos o mixtos, donde las temperaturas medias anuales se encuentran en un rango entre 12 °C y 16 °C. Se han observado, también, en biotopos asociados a los bosques con matorrales, pantanos, praderas y cultivos. Está presente tanto en zonas a nivel del mar hasta 1500 msnm.

Se encuentran distribuidas principalmente en Europa y oeste de Asia, aunque algunas especies habitan en América, limitadas por las montañas de Norteamérica y una especie, Triturus cristalinus, en Suramérica y norte de África.

Durante la reproducción, la cual es variable dependiendo de la altitud, latitud y condiciones hídricas, los machos sufren cambios morfológicos más evidentes que las hembras, pero en ambos sexos la piel es más brillante y los pliegues labiales se desarrollan más. Las hembras son más grandes que los machos y cuando empieza el periodo de vitalogénesis el abdomen se abulta y se pueden observar los ovocitos transparentes. Los machos desarrollan una cresta dorsal prominente y continua hasta la cola con colores llamativos.El cortejo suele iniciarse con un reconocimiento olfativo previo de los sexos; el macho corteja a la hembra en tres fases principales: orientación, exhibición y deposición del espermatóforo. Una misma hembra puede recibir espermatóforos de diferentes machos antes de iniciar la ovoposición.

La fecundación es interna, por tanto las hembras buscan lugares para realizar la puesta, la cual la realizan en plantas con hojas sumergidas, flexibles y anchas, doblando las hojas una vez ha hecho la ovoposición (por cada hoja un huevo). Cuando las larvas se desprenden de los huevos presentan unos filamentos a los lados de la cabeza llamados balancines, que le ayudan a mantener el equilibrio durante la natación, y branquias poco desarrolladas. A los pocos días desaparecen los balancines, crecen las branquias y se forma una cresta dorso-ventral. La madurez sexual y la longevidad dependen de la especie y el hábitat en el que se desarrolle el individuo.

Como se describió previamente, los tritones tienen la capacidad de regenerar epimórficamente. Este tipo de regeneración se comprobó experimentalmente en 1768 cuando Spallanzani mutiló las extremidades de salamandras y tritones y estas estructuras crecían nuevamente con funcionalidad normal. Se ha identificado, molecularmente, algunas proteínas que ayudan al proceso de regeneración, por ejemplo, el receptor de crecimiento TFP (ThreeFingerProtein) al cual se une la proteína Prod 1 que se encuentra en células del blastema y confiere la identidad próximo-distal en la estructura regenerada.

En 1779, Charles Bonnet comprobó que los tritones podían regenerar los ojos, para esto extirpó el cristalino derecho y observó el proceso de regeneración completa del mismo. En el embrión, el desarrollo del cristalino proviene de la capa embrionaria ectodérmica, más específicamente, de la superficie del ectodermo; mientras que, en el proceso de regeneración, el cristalino se forma a partir del borde del iris. El biólogo alemán Gustav Wolf eligió la extirpación del ojo en sus experimentos debido a que este tipo de mutilación no se da accidentalmente en la naturaleza, por lo cual el proceso de regeneración en el ojo no podía verse elegido por selección natural.

En la zona periférica de la retina se han observado células precursoras poco diferenciadas, neuroblastos no diferenciados y/o células germinales neuroepiteliales. Si estas células no están presentes, la regeneración empieza por el epitelio pigmentario de la retina, en donde las células del epitelio se despigmentan y empieza la proliferación. La zona de crecimiento determina el potencial crecimiento del ojo y aquí actúa el Factor de Crecimiento del Fibroblasto(FGF) que estimula la diferenciación de células ganglionares de la retina y ayuda a la expresión diferencial de los genes del cristalino. La vitamina A es importante para la formación de la rodopsina en los bastones de la retina.

La trombina tiene un rol importante en el desarrollo del cristalino, pero es inhibida en la formación del iris. Así mismo, la expresión de BMP ocurre en el iris y en todos los estadios de la regeneración del cristalino. Otra proteína que ayuda a la señalización de la formación del ojos es Wnt la cual es esencial en la diferenciación del epitelio del cristalino a células de fibra del cristalino, aumentando el marcador β-cristalino y la pérdida de función de β-catenina.

Los factores de transcripción Pax-6 y Six-3 median cascadas de señalización downstream en el desarrollo y la regeneración del cristalino. Pax-6 se ha considerado un gen de alta jerarquía debido a que es necesario y suficiente para la formación del cristalino en el desarrollo embrionario, pero no se conoce su rol en el proceso de regeneración a pesar de su expresión y se cree que ayuda a la proliferación del iris y la regulación en la síntesis del cristalino. Six-3 también se considera un gen de alta jerarquía y se expresa, junto con ácido retinoico, en el epitelio del cristalino en estadios tardíos del desarrollo del cristalino.

Se ha observado la expresión de genes homéoticos, como Pitx2,que codifica para un factor de transcripción que regula la expresión del gen lisil hidrolasa (enzima necesaria en la estabilización del colágeno hidrolizando la lisina); este último está involucrado en el desarrollo del ojo, dientes y órganos abdominales. Cuando Pitx2 se encuentra presente hace que se inhiba la formación del eje izquierda-derecha por lo que los órganos, como el corazón, el estómago y los ojos, son asimétricos. La expresión del gen homeótico está regulada por lo enhancers intrónicos ASE y Nodal.

La clasificación taxonómica del género Triturus ha dado origen a controversias, debido a que uno de los miembros ha sido clasificado de dieciocho especies. Además, se ha dividido en cuatro géneros: Lissotriton, Ommatotriton, Mesotriton y Triturus.

Se reconocen las siguientes especies:

1.Frost, Darrel R. 2013. Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 5.6 (9 de enero de 2013). Electronic Database accessible at http://research.amnh.org/vz/herpetology/amphibia/?action=references&id=32437. American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA.

2.Barni, S., Bertone, V., Croce, AC., Bottiroli, G., Bernini & F., Gerzeli, G. (1999). Increase in liver pigmentation during natural hibernation in some amphibians. Journal of Anatomy. 195: 19-25.

3.Barni, S., Nano, R. &Vignola, C. (1993). Changes of haemopoietic activity and characteristics of circulating blood cells in Trituruscarnifex and Triturusalpestris during the winter period. Comparative Haematology International. 3:159-163

4.Bely, A. & Nyber, K. (2010). Evolution of animal regeneration: re-emerge of a field. Trends in Ecology&Evolution. 25:161-170.

5.Díaz-Paniagua. C. (1986). Selección de plantas para la ovoposición en Triturusmarmoratus. Revista Española de Herpetología. 1: 317-328.

6.Discover life 2012, Discover life. Version 2012.2. http://www.discoverlife.org>. Downloaded on 23 November 2012

7.Duellman, W. E. &Trueb, L. (1994) Biology of Amphibians. Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore. ISBN 978-0-8018-4780-6.

8.Fasola, M., & Canova, L. (1992). Feeding habits of Triturus vulgaris, T. cristatus and T. alpestris(Amphibia, Urodela) in the northern Apennines (Italy). Bolletino di zoologia. 59: 273-280.

9.García-Cardenete, L., González de la Vega, J. P., Barnestein, J. A. M., Pérez-Contreras, J. (2003). Consideraciones sobre los límites de distribución en altitud de anfibios y reptiles en la Cordillera Bética (España), y registros máximos para cada especie. Acta Granatense. 2: 93-101.

10.Garza-García, A. Driscoll, P. &Brockes, J. (2010). Evidence for the Local Evolution of Mechanisms Underlying Limb Regeneration in Salamanders. Intregative and Comparative Biology. 50: 528-535. DOI 10.1093/icb/icq022.

11.Gilbert, 2005. Biología del desarrollo, Séptima edición. Sinauer Associates. Sunderland.

12.Groog, M., Call, M. &Tsonnis, P. (2006). Signaling during lens regeneration. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 17: 753-758.

13.Hidalgo-Villa, J., Pérez-Santigosa, N., Díaz-Paniagua, C. (2002). The sexual behaviour of the pygnmy newt, Trituruspygmaeus. Amphibia-Reptilia. 23: 393-405.

14.IUCN 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. . Downloaded on 24 November 2012.

15.Manteuffel, G. &Himstedt, W. (1978). The aerial and aquatic visual acuity of the optomotor response in the crested newt (Trituruscristatus). Journal of comparative physiology. 128: 359-365. DOI 10.1007/BF00657609.

16.Mitashov, V. (1996). Mechanisms of retina regeneration in urodeles. The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 40: 833-844.

17.NCBI 2012. NCBI National Center of Biotechnology Information (Taxonomy Broswer).Version 2012.2 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov>. Downloaded on 24 November 2012

18.Papavero, N., Puyol-Luz, JR. & Llorente, J. (2001). Historia de la Biología Comparada Desde el Génesis Hasta el Siglo de Las Luces. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Vol2. ISBN 978-968-36-9008-1.

19.Parker,T. &Haswell, W. (1991). Zoología. Cordados. Editorial Reverté. Barcelona. ISBN 84-291-1839.

20.Reques, R. (2000). Anfibios. Ecología y conservación. Serie Recursos Naturales de Córdoba. Diputación de Córdoba. Delegación de medio Ambiente y Protección Civil. 140pp.

21.Reques, R. (2004). Hábitats reproductivos de anfibios en la provincia de Cádiz: perspectivas para su conservación. Revista de la Sociedad Gaditana de Historia Natural. 4: 83-13.

22.Reques, R. (2009). Tritón pigmeo- Tritón pygmaeus. Enciclopedia Virtual de lo Vertebrados Españoles. Disponible en http://www.vertebradosibericos.org

23.Salvador, A. (1974). Guía de los anfibios y reptiles españoles. ICONA, Madrid.

24.Sheldrake, R. (2009). A new science of life. Kairós, S. A. Barcelona.

25.Shiratori, H., Yashiro, K., Shen MM. & Hamada, H. (2006). Conserved regulation and role of Pitx2 in situs-specific morphogenesis of visceral organs. Development. 133:3015–25. DOI 10.1242/dev.02470.

Triturus es un género de anfibios caudados de la familia Salamandridae, compuesto por una serie de especies de Europa y Asia que se encuentran en cuerpos de agua, como estanques poco profundos, lagunas, arroyos y aguas profundas tranquilas; y terrestres, como páramos, pantanos y bosques.

Este género se ha usado como especie indicadora debido a que su presencia o ausencia puede indicar la salud del ambiente, por ejemplo el pH del agua y otros contaminantes.

Es considerado por la IUCN como una especie de preocupación menor; sin embargo, las poblaciones de las distintas especies han ido decreciendo y en otras se encuentran estables.[cita requerida]

Vesilik ehk triiton (Triturus) on salamanderlaste sugukonda arvatud perekond kahepaikseid.

Loode-Euroopast on neid leitud 5 liiki,[1] Eestis elab 2 liiki: tähnikvesilik (Triturus vulgaris) ja harivesilik (Tritulus cristatus).

Vesilik ehk triiton (Triturus) on salamanderlaste sugukonda arvatud perekond kahepaikseid.

Triturus anfibio genero bat da, Caudata ordenaren barruko Salamandridae familian sailkatua.

Triturus anfibio genero bat da, Caudata ordenaren barruko Salamandridae familian sailkatua.

Triturus est un genre d'urodèles de la famille des Salamandridae[1].

Selon Amphibian Species of the World (7 mars 2014)[2] :

Les espèces de Triturus sont des grands tritons à la peau plus ou moins granuleuse. Ils mesurent de 12 à 18 cm de long selon les espèces. Comme les autres tritons ils sont munis d'une queue aplatie latéralement, à la différence de leurs cousines salamandres. Ces espèces présentent un dimorphisme sexuel assez marqué, le mâle et la femelle étant différents morphologiquement. Lors de la période de reproduction le mâle est différent de son apparence du reste de l'année et arbore une crête dorsale, dentée chez les tritons crêtés mais non denté chez les tritons marbrés. La femelle est plus grande que le mâle.

Les membres du genre Triturus passent une partie de l'année sur la terre ferme, mais sont aquatiques durant une partie de l'année autour de la période de reproduction. Ces tritons effectuent une parade nuptiale : le mâle nuptial se place devant la femelle et agite la queue le long de son corps, en direction de la femelle. Par ces mouvements, il diffuse vers la femelle des phéromones sécrétées par des glandes dorsales et cloacales, dans le but de séduire la femelle. Au contraire de nombreuses espèces d'amphibiens Anoures (grenouilles, crapauds et rainettes), les tritons, comme les autres membres de l'ordre des Urodèles, ne chantent pas lors de la période de reproduction.

À la fin de la parade nuptiale, le mâle dépose sur le fond un spermatophore, petite capsule blanche de forme allongée, comprenant les spermatozoïdes, que la femelle va recueillir par son cloaque. La fécondation sera alors interne. La femelle, après la maturation des œufs, les déposera un par un en général sur la face inférieure des feuilles de plantes aquatiques, qu'elle replie sur l'œuf avec ses pattes arrière. Quelques centaines d'œufs seront ainsi déposés. En quelques semaines les œufs éclosent et les larves (on ne parle pas de "têtards", ce terme étant réservés aux anoures) commencent leur développement. Strictement aquatiques au départ, les larves sont munies dans un premier temps de branchies externes souvent bien visibles. Elles acquerront au cours de leur développement des poumons, permettant aux adultes de vivre sur la terre ferme. plusieurs sont nécessaires aux larves afin d'accomplir la métamorphose.

Le genre Triturus est un ancien genre qui a connu de nombreuses évolutions. Il était jusqu'à récemment plus étendu qu'il ne l'est aujourd'hui, mais les études de classification phylogénétique des années 2000 ont montré que ce genre était polyphylétique[4],[5], ce qui a conduit à redistribuer de nombreuses espèces dans de nouveaux genres. Auparavant, plusieurs tentatives avaient déjà été faites par les herpétologues afin de classer plus précisément les espèces du genre à partir de la morphologie.

Steinfartz et. al[4] proposent la classification actuelle, en partie fondée sur des études précédentes[6],[7], où le genre Triturus est scindé en quatre genres dont trois nouveaux :

De nouvelles espèces sont ensuite distinguées et des sous-espèces sont élevées au rang d'espèce.

La nouvelle version restreinte du genre Triturus ne contient donc plus que le complexe des « tritons crêtés » (avec actuellement Triturus cristatus, Triturus carnifex, Triturus dobrogicus, Triturus macedonicus, Triturus ivanbureschi, Triturus karelinii et Triturus anatolicus) et celui des « triton marbrés » (Triturus marmoratus et Triturus pygmaeus).

Certains taxons du genre ont longtemps posé des problèmes aux taxonomistes, par exemple Triturus karelinii qui a été classé de dix huit façons différentes.

Les neuf espèces de ce genre se rencontrent surtout en Europe, et dans quelques régions du Moyen-Orient autour de la Mer Noire et de la Mer Caspienne, et jusqu'en qu'en Sibérie occidentale[1].

Le nom de ce genre vient de Triton, dieu grec fils de Poséidon, et du grec οὐρά Oura signifiant queue.

Triturus est un genre d'urodèles de la famille des Salamandridae.

Triturus é un xénero de anfibios caudados da familia dos salamándridos, composto por unha serie de especies presentes en toda Europa coa excepción da maior parte de Escandinavia, e na parte occidental de Rusia, Asia Menor ao longo da costa do mar Negro e na costa sur do mar Caspio.

Encóntranse en corpos de auga, como estanques pouco profundos, lagoas e regatos, e tamén en augas profundas tranquilas, e en zonas terrestres, como páramos, pantanos e bosques.

Especies deste xénero usáronse como indicadoras debido a que a súa presenza ou ausencia pode indicar a saúde do ambiente, por exemplo, o pH da auga e a presenza de contaminantes.

Triturus é un xénero de anfibios caudados da familia dos salamándridos, composto por unha serie de especies presentes en toda Europa coa excepción da maior parte de Escandinavia, e na parte occidental de Rusia, Asia Menor ao longo da costa do mar Negro e na costa sur do mar Caspio.

Encóntranse en corpos de auga, como estanques pouco profundos, lagoas e regatos, e tamén en augas profundas tranquilas, e en zonas terrestres, como páramos, pantanos e bosques.

Especies deste xénero usáronse como indicadoras debido a que a súa presenza ou ausencia pode indicar a saúde do ambiente, por exemplo, o pH da auga e a presenza de contaminantes.

Vodenjaci (mrmoljak, triton) (Triturus) su rod repatih vodozemaca iz porodice daždevnjaka (Salamandridae). Dugoljasta je tijela sa slabim i kratkim nogama. Na nogama ima jastučiće sa zrakom koji mu omogućuju hod po vodi. Ima rep koji je stisnut sa strane te mu to uvelike pomaže tijekom plivanja. Vodenjaci imaju veliku sposobnost regeneracije izgubljenih dijelova tijela, a to su najčešće noge, rep i oči. Zaštićen je te ga često susrećemo na hrvatskom prostoru.

Vodenjaci u proljeće borave u vodi (slatkovodne stajaćice - bare ili jezera). Kasnije izlaze i na kopno, gdje skrivajući se pod kamenjem, zimuju. Tijekom zimovanja, vodenjaci miruju i troše zalihe hrane iz tijela.

Doba parenja vodenjaka je u proljeće. Vodenjaci moraju svoja jaja položiti u vodu. Ženke svoja jaja, jedno po jedno, snesu na listove barskih biljaka. Njihove ličinke naliče na punoglavce koji u prvo vrijeme nemaju noge, a kasnije izgledaju kao mali vodenjaci te na glavi, sa strane, imaju škrge koje nalikuju malim pramenovima perja. Završna preobrazba ličinki je potpuna te im se škrge pretvaraju u pluća. U doba parenja, mužjacima nekih vrsta vodenjaka (veliki vodenjak), duž leđa naraste greben, a u većini vrsta donji dio tijela postane narančast.

Vodenjaci su grabežljivi, pa se i zbog toga hrane puževima, glistama te ličinkama kukaca. Hrane se slično kao i ribe.

Veliki vodenjak (Triturus cristatus) je dugačak oko 16 cm, na leđima je tamnozelenkast, a trbuh mu je žut s crnim pjegama. On nemože proizvoditi glas za privlačenje ženke, ali u proljeće, u doba parenja, na leđnoj strani tijela ima greben. Njihova je oplodnja unutarnja, a u koži imaju otrovne žlijezde kojima se štite od napadača. Imaju sposobnost i samosakaćenja jer u opasnosti mogu ostaviti rep napadaču. Taj se rep još miče te zbog toga zavarava neprijatelje koji misle da je to vodenjak.

Mali vodenjak (obični vodenjak, Lissotriton vulgaris, stari naziv Triturus vulgaris) i planinski vodenjak ( Lissotriton alpestris, stari naziv Triturus alpestris), iako u imenu imaju naziv "vodenjak", ne spadaju u ovaj rod.

Vodenjaci (mrmoljak, triton) (Triturus) su rod repatih vodozemaca iz porodice daždevnjaka (Salamandridae). Dugoljasta je tijela sa slabim i kratkim nogama. Na nogama ima jastučiće sa zrakom koji mu omogućuju hod po vodi. Ima rep koji je stisnut sa strane te mu to uvelike pomaže tijekom plivanja. Vodenjaci imaju veliku sposobnost regeneracije izgubljenih dijelova tijela, a to su najčešće noge, rep i oči. Zaštićen je te ga često susrećemo na hrvatskom prostoru.

Triturus 1815 è un genere di anfibi caudati della famiglia Salamandridae, comunemente noti come tritoni.

I tritoni hanno un corpo gracile e allungato, concluso da una lunga coda compressa lateralmente e provvista di lamina natatoria. La lingua è protrattile, i denti sono sia mascellari che vomero-palatini.

Possiede una spiccata capacità di rigenerazione degli arti e della coda.

Le uova vengono deposte singolarmente e fissate alle foglie delle piante acquatiche.

Le larve di tritone, e in genere di tutti gli urodeli, possiedono branchie ramificate che sporgono dai lati della testa, non coperte da opercolo come avviene invece nelle larve degli anuri.

Il genere è diffuso negli ambienti umidi di Europa e Asia occidentale.[1]

I tritoni, vivendo negli stagni con acqua ferma e paludosa e nei corsi d'acqua a lento scorrimento, si nutrono di larve di zanzare e altri piccoli insetti che cadono nell'acqua. In inverno si rifugiano sotto le radici degli alberi, nei boschi.

A primavera i tritoni abbandonano la terra per occupare le acque stagnanti, in vista dell'accoppiamento. In questo periodo i maschi assumono il carattere sessuale secondario della cresta sulla coda, che talvolta si prolunga sul dorso, come nel caso del Triturus cristatus.

Il tritone è uno degli anfibi il cui genoma è di dimensione maggiore di quello dei mammiferi (e dell'uomo in particolare, superando di cinque volte il numero di coppie di basi azotate di DNA).[2]

Comprende le seguenti specie:[1]

Sono conosciuti altresì col nome comune di tritone anche diversi altri anfibi urodeli appartenenti ai generi Ichthyosaura, Ommatotriton, Lissotriton :

Il tritone può essere allevato in acquario, preferibilmente in una vasca monospecifica in quanto non tutte le specie possono vivere pacificamente con altri animali, mentre vanno d'accordissimo con i loro conspecifici, tranne che nel periodo dell'accoppiamento.

Alcuni esemplari si possono abituare a vivere esclusivamente in acqua non compiendo la muta delle branchie. La soluzione migliore è tuttavia quella di allevarlo in un'acqua-terrario, in modo da rispettare la sua natura di anfibio.

In Italia il genere Triturus è considerato particolarmente protetto e la detenzione e l'allevamento sottoposti a stretto controllo o vietati, avendo l'Italia ratificata la Convenzione di Berna e i relativi allegati (Legge 503 del 05/08/1981 pubblicata su GURI n. 250 dell'11/09/1981[3]), nonché le successive modifiche (GURI n. 122 del 28/05/1998[4] e GURI n. 146 del 24/06/1999[5]).

In dettaglio sono richiamati:

Triturus 1815 è un genere di anfibi caudati della famiglia Salamandridae, comunemente noti come tritoni.

Triturus est genus amphibium Salamandridarum familiae.

Tritonai (lot. Triturus) – salamandrinių (Salamandridae) šeimos varliagyvių gentis.

Tritonai (lot. Triturus) – salamandrinių (Salamandridae) šeimos varliagyvių gentis.

Watersalamanders[1] (Triturus) zijn een geslacht van salamanders uit de familie echte salamanders (Salamandridae).[2] De groep werd voor het eerst wetenschappelijk beschreven door Constantine Samuel Rafinesque-Schmaltz in 1815.

Deze dieren hebben een lange en sterk afgeplatte staart en een uitgerekt, vis-achtig lichaam.

De salamanders zijn typische amfibieën; in de lente en deel van de zomer bevinden ze zich in het water, de rest van het jaar kruipen ze over het land en zien ze er anders uit; kleiner, donkerder, een ruwe huid en geen zichtbare rugkam.

Het geslacht Triturus omvat de bekende Europese salamandersoorten; Ze worden ook wel echte watersalamanders of kamsalamanders genoemd, hoewel onder deze laatste benaming niet T. marmoratus en T. pygmaeus vallen. Alle soorten komen voor in grote delen van Europa.[3]

Er zijn tegenwoordig negen soorten, inclusief de pas in 2016 wetenschappelijk beschreven soort Triturus anatolicus. Vijf soorten zijn ondergebracht in het geslacht Lissotriton, waaronder de bekende kleine watersalamander (L. vulgaris) maar deze wijziging is in de (niet recente) literatuur nog niet aangepast. De bandsalamander behoorde tot recentelijk ook tot dit geslacht, maar deze soort werd in 2004 bij het geslacht Ommatotriton ingedeeld.

Geslacht Triturus

Referenties

Bronnen

Watersalamanders (Triturus) zijn een geslacht van salamanders uit de familie echte salamanders (Salamandridae). De groep werd voor het eerst wetenschappelijk beschreven door Constantine Samuel Rafinesque-Schmaltz in 1815.

Triturus – rodzaj płazów ogoniastych z rodziny salamandrowatych. Obejmuje kilka gatunków traszek. Występuje od Wielkiej Brytanii poprzez większą część kontynentalnej Europy do zachodnich krańców Syberii, Anatolii i regionu Morza Kaspijskiego.

Traszki te zamieszkują i rozmnażają się w stawach o bogatej roślinności lub podobnych im siedliskach wodnych przez okres od dwóch do sześciu miesięcy w roku, resztę czasu spędzając w cienistych, bogatych w schronienia siedliskach lądowych w pobliżu miejsc ich rozrodu. Samce uwodzą samice w zrytualizowanych pokazach, pozostawiając pod koniec spermatofor podnoszony przez samice. Po zapłodnieniu samica składa od 200 do 400 jaj, zawijając je w liście roślin wodnych. Z jaj wylęgają się larwy rozwijające się w wodzie przez od dwóch do czterech miesięcy, nim ulegną przeobrażeniu w żyjące na lądzie osobniki młodociane.

Historycznie do omawianego rodzaju zaliczano większość europejskich traszek. Jednak taksonomowie podzielili go, wyróżniając rodzaje Ichthyosaura (traszka górska), Lissotriton i Ommatotriton. Natomiast najbliższymi krewnymi Triturus są przedstawiciele rodzaju Calotriton. Do Triturus zalicza się 8 gatunków zwierząt, podejrzewa się istnienie dziewiątego. Ich zasięgi występowania zachodzą na siebie. Może zachodzić krzyżowanie.

Choć nie grozi im wyginięcie w niedalekiej przyszłości, liczebność ich populacji zmalała, głównie z powodu utraty i fragmentacji siedlisk. Ucierpiały zarówno ich miejsca rozrodu, jak i bogate w kryjówki naturalne siedliska lądowe. W Europie wszystkie gatunki objęto ochroną prawną, podobnie jak niektóre ich siedliska.

Nazwę rodzajową Triturus wprowadził w 1815 polihistor Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, określając nią gatunek uznany za typowy Triturus cristatus (traszka grzebieniasta)[2], opisany już wcześniej pod nazwą Triton cristatus przez Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti w 1768. Jednakże Karol Linneusz wykorzystał nazwę Triton już 10 lat wcześniej na określenie ślimaków morskich (obecnie Charonia), wobec czego potrzebna była inna nazwa rodzajowa na określenie traszek[15][17].

Przed końcem XX wieku do Triturus włączano większość europejskich traszek. Wykazano jednak jego polifiletyzm i przeprowadzono zasadniczą rewizję[15]. Jego niektórych wcześniejszych przedstawicieli przeniesiono do trzech oddzielnych rodzajów: Lissotriton, Ommatotriton i Ichthyosaura. Monofiletyzm w ten sposób zredukowanego rodzaju Triturus wspierają dane molekularne[18] i synapomorfie, jak defekt genetyczny powodujący śmierć zarodków homomorficznych względem długiej lub krótkiej formy chromosomu 1[19].

Obecnie wyróżnia się 9 gatunków[15]:

Traszki określane po angielsku jako marbled newts i jako crested newts były długo uznawane za pojedyncze gatunki, określane nazwami naukowymi odpowiednio T. marmoratus i T. cristatus. Jednakże pomiędzy wyróżnianymi w ich obrębie podgatunkami zauważono znaczne różnice genetyczne, co doprowadziło do uznania ich za odrębne gatunki. Natomiast crested newts często opisuje się łącznie jako nadgatunek T. cristatus[15]. W ten sposób z Triturus marmoratus wydzielono T. pygmaeus, której status jako odrębnego gatunku potwierdzono w kolejnych badaniach[20]. Triturus ivanbureschi, opisany w 2013, prawdopodobnie stanowi w rzeczywistości dwa odrębne gatunki[16]. Wielstra i Arntzen (2016) przenieśli populacje traszek żyjące na północy azjatyckiej części Turcji (pierwotnie uznawane za traszki z gatunku T. ivanbureschi) do odrębnego gatunku Triturus anatolicus[21].

Triturus stanowi rodzaj raczej dużych traszek. Ich całkowita długość ciała zazwyczaj mieści się w przedziale pomiędzy 12 a 16 cm. Niekiedy dochodzi do 20 cm. Wyjątek stanowi Triturus pygmaeus o długości jedynie od 10 do 12 cm[30]. Wielkość zależy od płci i środowiska, w którym żyją. Samice większości gatunków są nieznacznie większe i mają proporcjonalnie dłuższy od samców ogon. T. carnifex wydaje się być większa w chłodniejszych rejonach swego zasięgu występowania[31][32].

Crested newts są ciemnobrązowe, z czarnymi plamkami po bokach i białymi kropkami u niektórych gatunków. Brzuch jest żółty do pomarańczowego z czarnymi plamami tworzącymi wzór charakterystyczny dla danego osobnika. Samice i osobniki młodociane pewnych gatunków cechują się żółtą linią biegnącą wzdłuż boku i ogona. Podczas okresu rozrodu następuje zmiana wyglądu, najsilniej zaznaczona u samców. Pojawia się grzebień skórny biegnący wzdłuż grzbietu i ogona, od którego bierze się nazwa traszki grzebieniastej. Może on osiągać 1,5 cm wysokości i u traszki grzebieniastej jest bardzo powyszczerbiany. Ponadto w sezonie rozrodczym samiec wykształca srebrzystobiały pasek wzdłuż boku i ogona[31][32].

Marbled newts zawdzięczają swą angielską nazwę ich zielono-czarnemu marmurkowanemu wzorowi ubarwienia. U samic pomarańczowoczerwona linia biegnie wzdłuż grzbietu i ogona. Grzebień samca jest mniejszy i bardziej mięsisty, niż u nadgatunku T. cristatus. Nie występują w nim też zazębienia. W czasie rozrodu traszki te mają także białawy pasek na ogonie[32].