pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

Macaca sylvanus inhabits Morocco, Algeria, and Gibraltar. The majority of M. sylvanus are found in the Middle and High Atlas mountains and in the Rif mountain regions of Morocco. A smaller population is located in the Tellian Atlas mountains of Algeria. Within the Atlas mountains, M. sylvanus is restricted to the Grand Kabylie mountains, the Petit Kabylie mountains, and the Chiffa Gorges. In Gibraltar, a population of about 200 are maintained by constant reintroduction of new animals. They are the only non-human primates in Europe.

Biogeographic Regions: palearctic (Native )

Barbary macaques prefer habitats consisting of high altitude mountains, cliffs, and gorges. Although they prefer high altitude habitats, up to 2600 m, they can also be found at sea level. Their primary habitat is cedar forests, but they are also found in mixed forests of cedar and holm-cork oak, pure oak forests, shrubby rock outcrops along coasts, and occasionally in grasslands at low elevations. During the winter they are highly arboreal, but become more terrestrial during summer.

Range elevation: 0 to 2600 m.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: savanna or grassland ; forest ; scrub forest ; mountains

Barbary macaques typically live 22 years in the wild. Males rarely live more than 25 years, and females appear to live slightly longer than males. Infants have a 10% mortality rate in the wild. No data has been reported for captive Barbary macaques.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 22 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 22 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 22.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 20.0 years.

Average lifespan

Sex: male

Status: captivity: 17.0 years.

Barbary macaques are covered in thick fur that presumably helps protect them from cold temperatures. Body color ranges from yellowish-gray to darker grayish-brown. Their chests and stomachs are much lighter than the rest of their bodies while their faces are often dark pink. Barbary macaques have noticeably short tails, ranging from 1 to 2 cm long. Females average 450 mm from head to tail, weigh about 11 kg, and display estrus with large anogenital swellings. Males are larger, weighing 16 kg and range in length from 550 to 600 mm. Like all cercopithecids, Barbary macaques have large cheek pouches for carrying food. The dental formula of a Barbary macaque is I2/2, C1/1, P2/2, M3/3.

Range mass: 11 to 16 kg.

Range length: 450 to 600 mm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: male larger; sexes colored or patterned differently

Due to dramatic changes in climate in the mountains throughout the year, the diet of Barbary macaques changes seasonally. During spring, they eat various vegetation and feast on caterpillars that live in oak tress. By summer, fruits are plentiful along with other small seeds, roots, and fungi. Barbary macaques become terrestrial foragers during spring and summer to acquire these foods. Occasionally, they also eat small vertebrates such as frogs and tadpoles. Oaks produce acorns during fall, which Barbary macaques feed on during this time. During periods of particularly high mast production, macaques may subsist on acorns for more than half the year. During winter, ground forage becomes limited and Barbary macaques become arboreal again. Arboreal forage during winter consists of the leaves, seeds, and bark of evergreens.

Animal Foods: amphibians; insects

Plant Foods: leaves; roots and tubers; wood, bark, or stems; seeds, grains, and nuts; fruit; flowers

Other Foods: fungus

Primary Diet: omnivore

Macaca sylvanus is omnivorous and consumes insects, fruit, and other plant materials. This species is an important seed disperser in the mountains where they reside. They are also an important prey item for eagles, golden jackals, and red foxes. Macaca sylvanus is host to a number of ecto- and endoparasites including flatworms, roundworms, sucking lice, parasitic Protozoa (Giardia), and the viruses that cause canine distemper (Paramyxoviridae) and encephalomyocarditis (Picornaviridae), which can sometimes be fatal in M. sylvanus.

Ecosystem Impact: disperses seeds

Commensal/Parasitic Species:

Due to their low numbers in the wild, Barbary macaques are not commonly used in labs, but some labs still utilize them for biomedical research. There is also a small illegal pet trade for them. In Gibraltar they attract a large number of tourists.

Positive Impacts: pet trade ; ecotourism ; research and education

Barbary macaques Macaca sylvanus occasionally raid gardens or farms, which has led to trapping and illegal poaching.

Negative Impacts: crop pest

The primary predator of Barbary macaques are large eagles that patrol the mountains for prey. At least one troop member is constantly vigilant for danger. Barbary macaques give a special high-frequency "ah-ah" alarm call when eagles are spotted. Upon hearing this call, they quickly escape to the lower canopy to hide. Less common predators consist of golden jackals and red foxes.

Known Predators:

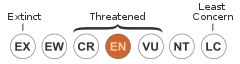

Barbary macaques are listed as endangered on teh IUCN's Red List of Threatened Species. In Morocco and Algeria they are a federally protected species, but are still in danger of local extinction. Their greatest threat is habitat loss, predominantly from logging. As a result, macaques are pushed farther up mountains into nutrient poor areas where survival is more difficult. Resource competition with domestic goats has become an increasing problem as well. Recently, Barbary macaques have changed their feeding patterns to incorporate more bark and flowers so they can survive. Minor threats include trapping, illegal poaching, and death by herding dogs. About 300 infants are taken out of Morocco annually for pet trade. Barbary macaques are listed under Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

CITES: appendix ii

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: endangered

Barbary macaques display a variety of facial expressions to show emotions. Females show rounded-mouth threats towards other females as a sign of aggression and dominance. Bared teeth show submission. Lip-smacking and teeth-chattering are signs of appeasement which are often directed at a dominant individual or towards infants. Barbary macaques also display relaxed, open-mouthed, play faces which are thought express happiness.

Sounds is a crucial part of communication in primates. Barbary macaques scream and grunt at trespassing troops. They also use a loud, high-pitched "ah-ah" call to warn troop members of potential danger. Mating calls from females during copulation have been shown to increase the likelihood of ejaculation in males. Barbary macaques are capable of recognizing individuals by calls, and mothers can recognize their infants by their cries. Young cry a string of high-pitched calls at dusk, presumably to find their mother in sleeping clusters. Troops are familiar with the vocalizations of neighboring troops as well. Studies have shown calls are learned through experience and different social groups may use different dialects.

Communication Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Barbary macaques are polygynandrous, as males and females have multiple mates. Females display estrus with large anogenital swellings. Females initiate and terminate matings and compete with each other for mates by interrupting copulation. Male rank has little effect which individuals females choose to mate with. By the time estrus is complete, each female has mated with all or nearly all males in her troop. Often, females continue to copulate even when conception is impossible. At the end of breeding season, the combined number of copulations by all the females in a troop can number in the hundreds. Female promiscuity is thought to mask the true identity of an infant's father resulting in paternal support from more than one male.

Although male Barbary macaques have little influence over who they mate with, dominant individuals tend to mate more often than subordinates and tend to mate more with dominant females. Despite competition for females, male Barbary macaques show high tolerance for each other. They compensate for intense sperm competition by having large testical-size to body-size ratios. Older males have more breeding success than younger individuals. Males use three mating strategies when attracting females. Individuals using "proximity-possession" remain in close proximity to a female, which usually ensures one's opportunity to mate. Others use the "pertinacious strategy", where they closely follow a female until they are noticed and allowed to mate. Lastly, lowest ranking males use a "peripheralize and attract strategy", where they stay far away from the female, but shake branches or carry other infants in full view of the female in order to attract her attention. Successful males then mate with a female, only mounting her once for a short period of time before both part ways.

Barbary macaques are very social. Once infants are born, the entire troop takes part in caring for infants (i.e., cooperative breeding).

Mating System: polygynandrous (promiscuous) ; cooperative breeder

Mating season of Barbary macaques begins in November and ends in December. Gestation last for 164.2 days, on average, and one offspring is usually born between April and June. Barbary macaques typically reach sexual maturity around 46 months of age, regardless of gender. Females remain in estrus for about 1 month and have their first offspring around 5 years of age. Interbirth interval ranges from 13 to 36 months, and the first offspring is generally smaller than subsequent offspring. Females reach menopause during the last 5 years of their lives, though estrus may continue for a few more years. Females often continue to copulate, even when conception is no longer possible.

Although no formal research has been conducted on Barbary macaque infants, in general, newborn primates are altricial and require intense care. Female rhesus macaque, a close relative to Barbary macaques, stay in close contact with their newborns for the first 3 months after birth. In young macaques, weight is often used as a substitute for age. Rhesus macaques are weaned between 1,300 to 1,400 grams. Depending on environmental conditions and resource abundance, infants can be weaned between 200 to 362 days. Average birth weight for Barbary macaques is 450 g.

Breeding interval: Barbary macaques breed once a year.

Breeding season: November to December

Range number of offspring: 1 to 2.

Average number of offspring: 1.

Range gestation period: 158 to 170 days.

Average gestation period: 164.2 days.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 46 months.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 46 months.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization ; viviparous

Average birth mass: 450 g.

Average number of offspring: 1.5.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

Sex: male: 2007 days.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

Sex: female: 1399 days.

Barbary macaques live in matrilineal societies with youngest daughter ascendancy, thus newborn females outrank everyone else in the immediate family except their mothers. Alloparenting is common among Barbary macaques. The entire troop shows interest in newborns and displays friendly teeth-chattering or lip-smacking towards infants. Unlike many primates, Barbary macaques actively take care of unweaned infants more than weaned infants. Females often help "baby-sit" infants of other females. Infants of closely related females and of the highest ranking female usually receive the most attention. Nulliparous females (i.e., females without offspring) engage in infant-carrying more than other females, but this has not been linked to an increase in the survival of their own infants. Females who have recently lost infants are also more likely to carry others' infants. Research suggests that extensive infant handling may allow females to rise in rank. Infants receiving extra care do not experience higher survival rates than those who do not receive extra care.

Due to the promiscuous mating system of Barbary macaques, males have no way of knowing which infant is theirs. As a result, they provide paternal care to infants in their troop. For example, adult males group around infants to protect them from approaching predators. In general, males appear to show preference to male infants. Young-adult males tend to develop strong bonds with male infants, and older adult males prefer to take care of any infants from high-ranking females. Females appear to show mating preference to males that provide the most paternal care to their offspring.

Parental Investment: altricial ; male parental care ; female parental care ; pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Male, Female); pre-independence (Protecting: Male); post-independence association with parents; extended period of juvenile learning; maternal position in the dominance hierarchy affects status of young

Ar makak golf(Daveoù a vank) a zo ur makak, Macaca sylvanus an anv skiantel anezhañ.

Ar makak nemetañ an hini eo hag a vev en Afrika[1] : e gavout a c'heller e menezioù Atlas Aljeria ha Maroko. Kavet e vez ivez e Jibraltar m'eo bet degaset, ar pezh a ra dezhañ ar primat nemetañ en Europa, a-gevret gant Homo sapiens evel-just.

Ar makak golf(Daveoù a vank) a zo ur makak, Macaca sylvanus an anv skiantel anezhañ.

La mona de Gibraltar (Macaca sylvanus) és un simi del gènere Macaca que només presenta un rudiment de cua. Es troba a les muntanyes de l'Atles d'Algèria i Marroc amb una petita població probablement introduïda, a Gibraltar; és un dels simis més ben coneguts. Al seu lloc d'origen viu entre els boscos d'alzines.

El seu pelatge és de color marró-groguenc a gris, amb les parts de sota més clares; creix fins a un màxim de 75 cm i arriba a pesar uns 13 kg. El seu rostre és rosa fosc i la seva cua és vestigial. Els braços són més llargs que les cames. Les femelles són una mica més petites que els mascles.

Habiten els boscos de cedres, pins i alzines. Es troba més freqüentment a partir dels 2.100 metres d'altitud. És un animal diürn arborícola i terrestre. És principalment herbívor, però també insectívor. És gregari matriarcal, de 10 a 30 individus. La temporada d'aparellament va de novembre a març i el període de gestació és de 147 a 192 dies. Arriben a la maduresa sexual als tres o quatre anys i poden viure 20 anys o més.

Està amenaçat el seu hàbitat; s'estima que en llibertat n'hi ha de 12.000 a 21.000.[1]

Prosperen a Gibraltar amb uns 230 individus, a més hi ha la llegenda que, mentre n'hi hagi, Gibraltar serà una colònia britànica.

La mona de Gibraltar (Macaca sylvanus) és un simi del gènere Macaca que només presenta un rudiment de cua. Es troba a les muntanyes de l'Atles d'Algèria i Marroc amb una petita població probablement introduïda, a Gibraltar; és un dels simis més ben coneguts. Al seu lloc d'origen viu entre els boscos d'alzines.

Makak magot či magot bezocasý (Macaca sylvanus) je opice z čeledi kočkodanovitých. Jde o jedinou opici (mimo člověka), jejíž areál přirozeného výskytu zasahuje na evropský kontinent. Jediná evropská kolonie těchto opic se nachází na Gibraltaru. Patří mezi tzv. opice Starého světa (úzkonosé opice).

Magot – z port. magot, a to z hebr. Magog,[2] názvu biblické země a kmene, symbolizující nepřítele Božího království na konci časů; někdy chápáno jako synonymum k Babylónu.[3] Ve středověkých romancích bylo tohoto výrazu užíváno jako symbolu ošklivosti.[4]

Makak magot je chován v takřka 150 evropských zoo.[5] V rámci Česka jsou k vidění ve dvou zoo:

Makak magot či magot bezocasý (Macaca sylvanus) je opice z čeledi kočkodanovitých. Jde o jedinou opici (mimo člověka), jejíž areál přirozeného výskytu zasahuje na evropský kontinent. Jediná evropská kolonie těchto opic se nachází na Gibraltaru. Patří mezi tzv. opice Starého světa (úzkonosé opice).

Berberaben (Macaca sylvanus) er en haleløs makakabe, der findes i skovene i Atlasbjergene i Algeriet og Marokko. Desuden findes en lille population i Gibraltar, men det er usikkert hvorvidt de er blevet indført af mennesker hertil. På grund af denne forekomst omtales berberaben undertiden som gibraltaraben. Udover mennesket er det den eneste primatart der i dag lever vildt i Europa.

Pelsen på denne abeart er typisk gulbrun eller grå med en lysere underside. De største eksemplarer bliver op til 75 cm høje og vejer indtil 13 kg. Hunner når normalt en størrelse der er mindre end hannernes. Ansigtet er farvet mørk-lyserød, mens halen er reduceret til et rudiment, og forlemmerne er længere end baglemmerne.

Berberaber bebor skovområderne med fyr, eg og cedertræer i de nordafrikanske bjerge og kan findes i op til 2.100 meters højde. Derved er det den eneste makak-art der lever udenfor Asien. Det er et dagaktivt dyr som i løbet af dagen både opholder sig i træerne og på jorden. Det er et flokdyr som danner blandede grupper der består af mellem 10 og 30 hanner og hunner. Flokken ledes af en matriark og hierarkiet bestemmes ud fra slægtskabet til hende. I modsætning til de fleste arter af primater deltager hannerne i yngelplejen, og de tilbringer meget tid med at lege og pleje dem; derved opbygges der stærke sociale bånd også mellem hannerne og deres afkom.

Berberaber er primært planteædende og føden består hovedsageligt af blade, rødder og frugt, men de tager indimellem også insekter. I dagtimerne patruljerer flokken deres territorium, der kan strække sig over flere kvadratkilometer. Normalt lever berberaben fredeligt ved siden af andre primatarter, og kan fx dele vandhuller med dem uden der opstår konflikter. Berberaber bevæger sig energisk rundt på alle fire lemmer, men kan rejse sig på bagbenene; fx for at undersøge omgivelserne for farer.

Parringssæsonen løber fra november til marts, og efter en drægtighedsperiode på 147 til 192 dage føder hunnen typisk én unge; tvillinger er en sjældenhed. Aberne bliver kønsmodne efter 3 til 4 år og kan blive 20 år gamle eller ældre.

Berberabernes habitat i Atlasbjergene er truet af især træfældning; arten er derfor betegnet som sårbar på IUCN's Rødliste. Lokale bønder betragter også aberne som skadedyr og jages derfor. Derfor findes der i dag kun mellem 1.200 og 2.000 eksemplarer tilbage i naturen, hvor arten tidligere har været vidt udbredt over hele Nordafrika og måske Sydeuropa.

Den eneste vilde bestand af berberaber i Europa findes i Gibraltar, den udgøres af omkring 230 individder, men er i modsætning til den nordafrikanske bestand ikke truet. Dette skyldes primært den intensive vildtpleje som Gibraltars myndigheder har iværksat.

Aberne regnes som Gibraltars vigtigste seværdighed, og den mest populære kaldes Queen's Gate og holder til ved The Apes' Den. Ved at tage op med svævebanen Cable Car Gibraltar kommer turisterne her ganske tæt på aberne, der med tiden er blevet vænnet til menneskelig kontakt; dog vil de reagere med bid, hvis de generes.[1] Den efterhånden ganske intensive interaktion med mennesker førte dog til at flokkene socialt brød sammen, da dyrene blev afhængige af mennesker. De begyndte at finde føde i byen og ødelagde dermed ofte genstande, køretøjer og tøj i deres jagt på mad. Derfor er det i dag forbudt at fodre aberne i Gibraltar.[2]

En populær myte fortæller at så længe berberaberne findes på Gibraltarklippen, så vil den forblive et britisk territorium, områdets status er genstand for en disputs mellem Spaniens og Storbritanniens regeringer. I 1942 da population var svundet ind til en håndfuld på syv aber beordrede Winston Churchill derfor at deres antal skulle suppleres med nye eksemplarer hentet i Marokko og Algeriet.[3]

En anden historie fortæller at aberne kender en 24 km lang undersøisk tunnel der forbinder Gibraltar med Afrika. Og de skulle have benyttet den til at nå frem til Gibraltar.

Igennem historien er berberaben i flere tilfælde blevet brugt som substitut for mennesker. Især indenfor lægevidenskaben. Eksempelvis skyldes de fejlagtige antagelser, som den antikke og i middelalderen autoriattive anatom Galen, gjorde om den menneskelige anatomi, at han benyttede berberaber i sine studier, da han ikke havde adgang til lig fra mennesker; dengang i romersk lov var det forbudt at dissekere menneskekroppe.

Berberaben (Macaca sylvanus) er en haleløs makakabe, der findes i skovene i Atlasbjergene i Algeriet og Marokko. Desuden findes en lille population i Gibraltar, men det er usikkert hvorvidt de er blevet indført af mennesker hertil. På grund af denne forekomst omtales berberaben undertiden som gibraltaraben. Udover mennesket er det den eneste primatart der i dag lever vildt i Europa.

Der Berberaffe (Macaca sylvanus), auch Magot genannt, ist eine Makakenart aus der Familie der Meerkatzenverwandten. Er ist vor allem dafür bekannt, dass er außer dem Menschen die einzige freilebende Primatenart Europas ist.

Berberaffen erreichen eine Kopfrumpflänge von 55 bis 63 Zentimetern und ein Gewicht von 9,9 bis 14,5 Kilogramm. Männchen werden deutlich schwerer als Weibchen und haben deutlich längere Eckzähne als die Weibchen. Das Fell dieser Tiere ist einheitlich gelblich-braun oder graubraun gefärbt, das Gesicht ist dunkelrosa. Wie alle Makaken haben sie Backentaschen zum Verstauen der Nahrung. Berberaffen sind schwanzlos.[1]

Berberaffen leben als einzige Makakenart nicht in Asien, sondern im Rifgebirge und im Mittleren Atlas in Marokko und in der großen und kleinen Kabylei in Algerien, in Höhen von 400 bis 2300 Metern über dem Meeresspiegel, sowie in Gibraltar. Die dortige Population wurde jedoch vom Menschen eingeführt. Lebensraum dieser Tiere sind Eichen-, Tannen- und Zedernwälder, mit Atlas-Zeder, Spanischer Tanne, Algerischer Eiche, Korkeiche, Portugiesischer Eiche und Steineiche als dominierende Baumarten.[2] Der Berberaffe kommt auch mit felsigem, zerklüftetem Terrain gut zurecht.[1]

In den Warmzeiten des Mittel- und Altpleistozän kam der Berberaffe auch im südlichen, westlichen und mittleren Europa vor. Fossile Nachweise der Art gibt es unter anderem aus Norditalien[3], von Sardinien, aus Deutschland, Kroatien, Österreich, dem westlichen Rumänien, aus der Slowakei, Tschechien, Ungarn[4] und vom Grund der damals noch trockenen Nordsee.[5]

Berberaffen können gut klettern, verbringen aber einen Großteil des Tages auf dem Boden. Wie alle Altweltaffen sind sie tagaktiv.

Sie leben wie alle Makaken in Gruppen, deren Größe variabel ist, die übliche Größe beläuft sich auf 12 bis 88 Tiere. Berichten zufolge spalten sich Gruppen in kleinere Einheiten auf, wenn sie zu groß werden. Da die Weibchen zeitlebens in ihrer Geburtsgruppe bleiben, bilden in der Regel einige nahe verwandte Weibchen den Kern der Gruppe. Die Männchen etablieren eine Hierarchie durch Kämpfe, die stärksten und beliebtesten Männchen werden dominant und leiten die Gruppe. Dominante Männchen genießen Vorrechte beim Futter und bei der Paarung, prinzipiell kann sich aber jedes Männchen fortpflanzen. Es sind territoriale Tiere, die Größe des Revieres ist variabel und hängt unter anderem vom Nahrungsangebot und von menschlichen Störungen ab.[1]

Berberaffen sind Allesfresser, die Früchte, Samen, Blätter, Kräuter, Knospen, Flechten, Pilze und Wurzeln, aber auch gelegentlich Insekten (Ameisen, Käfer, Motten, Schmetterlinge, Raupen, Termiten, Wasserläufer), Vogeleier, Würmer, Tausendfüßer, Spinnen oder auch Skorpione zu sich nehmen. Die Nahrungssuche nimmt etwa ein Viertel ihrer aktiven Zeit in Anspruch.[2] In den kühleren Wintermonaten bilden Rinde und Baumnadeln einen wichtigen Nahrungsbestandteil.[1]

Vorrangig paaren sich die Weibchen mit den höhergestellten Männchen, obwohl sich vielfach alle männlichen Tiere fortpflanzen. Es gibt keine feste Paarungszeit; diese hängt von den klimatischen Bedingungen ab. Nach einer rund 165-tägigen Tragzeit bringt das Weibchen meist ein einzelnes Jungtier, sehr selten aber auch Zwillinge, zur Welt. Die Neugeborenen wiegen rund 500 Gramm und haben ein dünnes, schwarzes Fell, das sich innerhalb von 4 Monaten hellbraun umfärbt, bis sie die Farbe der Erwachsenen haben.

Bedingt durch das promiskuitive Paarungsverhalten kümmern sich auch die Männchen um die Jungtiere. Sie pflegen deren Fell, tragen sie herum und spielen mit ihnen, ohne zu wissen, ob sie tatsächlich der Vater sind.

Nach rund sechs bis zwölf Monaten werden die Jungtiere entwöhnt. Weibchen werden mit 4 bis 6 Jahren und Männchen mit 5 bis 8 Jahren geschlechtsreif; die Männchen müssen zu diesem Zeitpunkt ihre Geburtsgruppe verlassen. Berberaffen können 20 bis 30 Jahre alt werden. Am Affenberg Salem in Deutschland, wo 200 Individuen in 3 Clans und ein Teil der Weibchen mit hormoneller Empfängnisverhütung leben, wurde eine Lebenserwartung von 25 Jahren für Männchen und etwa 30 für Weibchen beobachtet.

Schriftliche Bemerkungen über den Berberaffen gibt es schon in der Antike durch Ägypter, Phönizier, Etrusker und Griechen (u. a. durch Aristoteles).[6] Conrad Gessner erwähnte die Art 1551 im ersten Band seiner Historia animalium (Quadrupedes vivipares). Der schwedische Naturwissenschaftler Carl von Linné, der mit der binären Nomenklatur die Grundlagen der modernen botanischen und zoologischen Taxonomie schuf, benannte die Art 1758 in seiner Systema Naturæ unter dem Namen Simia sylvanus und gilt damit als Autor der Erstbeschreibung. Der Berberaffe zweigte als erste Art von der Hauptentwicklungslinie der Makaken ab und ist damit die basale Schwesterart aller asiatischer Arten[7]. Innerhalb der Art werden keine rezenten Unterarten unterschieden.[1] Einige im Pliozän in Europa vorkommenden Makakenformen werden dagegen von einigen Autoren als Unterarten von Macaca sylvanus klassifiziert. Dabei handelt es sich um Macaca sylvanus florentina (spätes Pliozän, Süd- und Mitteleuropa), M. s. prisca (mittleres Pliozän, Süd- und Mitteleuropa) und M. s. major (spätes Pliozän, Sardinien).[8]

In Nordafrika gibt es nach einer Schätzung aus dem Jahr 2013 weniger als 7000 Tiere;[1] der Bestand geht aufgrund der Zerstörung ihres Lebensraumes weiter zurück. In Libyen und Ägypten sind sie schon um 1800 ausgerottet worden, heute leben rund 70 % aller Berberaffen in Marokko. Die IUCN listet sie als „stark gefährdet“ (endangered).[9]

Obwohl Fossilienfunde darauf schließen lassen, dass die iberische Halbinsel in vorgeschichtlicher Zeit von Berberaffen besiedelt war, geht die heutige Population auf dem Felsen von Gibraltar mit hoher Wahrscheinlichkeit auf den Einfluss des Menschen und dessen Reiseverhalten zurück. Denkbar ist eine Einführung während der arabischen Herrschaft in Südspanien zwischen 711 und 1492; die ersten schriftlichen Berichte stammen aus dem Jahr 1704. Da einer Legende zufolge Gibraltar solange in britischer Hand bleibt, solange dort Berberaffen leben und der Bestand 1942 auf wenige Tiere gesunken war, ließ Winston Churchill einige Tiere aus Marokko auf der Halbinsel aussetzen. Genetische Untersuchungen brachten das Ergebnis, dass die derzeitige Population auf zwei Wurzeln zurückzuführen ist, eine algerische und eine marokkanische. Heute leben in Gibraltar rund 240 Tiere.

1969 wurde der Tierpark La Montagne des Singes in der Gemeinde Kintzheim in der Region Elsass in Frankreich als Attraktion für Touristen eröffnet. Die Berberaffen adaptierten sich im dortigen Klima schnell und die vielen Geburten sorgten dafür, dass bald weitere Freigehege nach demselben Konzept angelegt werden konnten, von denen jedes etwa 150 bis 250 Tiere beherbergt:

Die mehrmonatige Winterpause (etwa Mitte November bis Mitte März) ist besucherfrei und dient als Paarungszeit.

Der Berberaffe (Macaca sylvanus), auch Magot genannt, ist eine Makakenart aus der Familie der Meerkatzenverwandten. Er ist vor allem dafür bekannt, dass er außer dem Menschen die einzige freilebende Primatenart Europas ist.

iddew amaziɣ (Assaɣ ussnan: Macaca sylvanus) d talmest n iɣersiwen yeṭṭafaren tawsit n iddew

Iddew amaziɣ d yiwen n iddew ur nli (ur nesɛi) asallaf yettidir deg idurar n Aṭlas deg tmurt n Iqbayliyen d Lezzayer d Umeṛṛuk d Gibraltar

Deg waṭas n tutlayin yettwanefk-as-d uglam n Amaziɣ (Barbary) acku yettidir deg wakal n imaziɣen akken daɣen ila (yesɛa) ismawen n iden s Tmaziɣt amdya (Abaɣus, Azeɣṭuṭ, Abiddaw ...)

Ini n yiddew amaziɣ d aras imal ar tewṛeɣ ma d idis-is adday imal ar uzunɣid, Ini n wudem-is d azwawaɣ yeɣman (qessiḥen), Tiddi-ynes tafellayt i yezmer ad igmu 75 cm. Ma d azuk-is 13 kg, teɣzi n ifassen-is tugar agla n iṭarren-is

Tasemhuyt n umercel n telmest-a tettili-d gar n wember ar Meɣres, Tawtemt tettarew-d anagar yiwen n iddew seld Tadist yettaṭafen gar n 147 ar 192 n wussan, iddew amaziɣ yezmer ad idder ar 20 n iseggasen

iddew amaziɣ (Assaɣ ussnan: Macaca sylvanus) d talmest n iɣersiwen yeṭṭafaren tawsit n iddew

Iddew amaziɣ d yiwen n iddew ur nli (ur nesɛi) asallaf yettidir deg idurar n Aṭlas deg tmurt n Iqbayliyen d Lezzayer d Umeṛṛuk d Gibraltar

A mona de Berbería u macaco de Berbería (Macaca sylvanus (L., 1758)) ye una especie de primates d'a familia Cercopithecidae que se distribuye por Marruecos, Archelia y Chibraltar. Representa chunto con a especie humana a sola especie de primate salvache no introdueita en o continent europeu, a on que ye present en o Pleistoceno (plegaba en os periodos interglaciars dica Alemanya y Gran Bretanya). Tamién ye o solo miembro d'o suyo chenero present fuera d'Asia. En Espanya, por estar o suyo solo reducto d'habitat en Europa en o penyón de Chibraltar, se la conoix tamién como mona de Chibraltar.

Ye conoixida fosil de la zona pirenenca d'o Pleistoceno inferior (chacimiento de Montousé) y d'o Pleistoceno meyo (chacimiento de Montsaunès) correspondendo a la fin d'o Mindel u a lo interglaciar Mindel-Riss, fósils que en primeras fuoron descritos baixo o nombre de Macaca tolosanus.

Magòt, makak magòt (Macaca sylvanus) – to je môłpa z rodzëznë makakòwatëch. Òn żëjë ni leno w ekwatorowim lasu wiedno zelonym, ale téż w Eùropie.

Li mårticot d' Djibraltar[1] u mårticot amazir[2], c' est l' seu séndje d' Urope, ki dmeure dins les rotches des falijhes di Djibraltar, mins k' i gn aveut eto, divins l' tins e l' Andalouzeye.

No d' l' indje e sincieus latén : Macaca sylvanus

C' est on ptit rabodjou séndje, sins cawe.

Li trô do nez s' drove ådzeu d' on rond muzea.

Li nez n' est waire bricant, mins les årvôs des sorcis bén.

Il a des longs pwels, e-n on spès poyaedje (po poleur sopoirter les iviers), pus påle sol vinte et les costés dvintrins des mimbes; les poys del figueure sont pus court; li biesse est pelêye åtoû des ouys.

Li toû do cou est et l' påme des pates est rôze djaenåsse.[3]

A Djibraltar, end a sol pegnon, çou ki fwait l' plaijhi des tourisses.

E l' Afrike bijhrece, on l' ritrove coranmint ezès bwès d' montagne (mins nén a Nonne), la k' i sierveut d' nouriteure å liyon d' l' Atlasse et al pantere di l' Atlasse.

E Marok, metans, end a dins l' Mîtrin Atlasse diski dins l' Mîtrin Grand Atlasse (Ayites Bou Oulli). Adon-pwis, dins l' Rif, aprume e payis Jbala (a Nonne di Tandjî).[4]

Li no d' ene aiwe d' Andalouzeye, dilé Aldjezirasse, Guadalcorte, e-n arabe "واد القرص" (ouwed el qard) vout dire l' aiwe ås mårticots.

Li mårticot d' Djibraltar u mårticot amazir, c' est l' seu séndje d' Urope, ki dmeure dins les rotches des falijhes di Djibraltar, mins k' i gn aveut eto, divins l' tins e l' Andalouzeye.

No d' l' indje e sincieus latén : Macaca sylvanus

Берберско макаки (науч. Macaca sylvanus)[3] — вид на макаки единствено кое се наоѓа на територија надвор од Азија и има закржлавена опашка.[4] Може да се сретна на падините на планината Атлас во Алжир и Мароко и малубројна популација која била пренесена од Мароко до Гибралтар, берберското макаки е најдобро познат мајмун од Европа species.[5]

Берберското макаки е од интерес бидејќи мажјаците имаат нетипична улога да се грижат за младите. Поради несигурноста наза татковството, мажјаците подеднакво се грижат за сите младенчиња. Општо, Берберските макаки од сите возрасти и пол придонесуваат за грижата на младите.[6]

Исхраната на макикито се содржи претежно од растенија и инсекти во зависност од животната средина. Мажјаците живеат и до 25 години додека пак женките можат да живеат и 30 години.[4] Покрај луѓето, тие се единствените слободни примати во Европа. Иако видот вообичаено се нарекува „Берберски примат“, берберското макаки е всушност вистински мајмун. Неговото име потекнува од Берберското крајбрежје во северозападна Африка.

Берберските макаки кои живеат во Гибралтар се единствената група која живее надвор од Северна Африка и единствените диви мајмуни на тлото на Европа. Во Гибралтар живеат отприлика 230 макаки.[7]

Овој мајмун има жолто-кафена боја па се до сива со посветло обоен стомачен дел. Берберското макаки има должина на телото од 556,8 мм кај женките и 634,3 мм кај мажјаците со измерени тежини од 9,9±1.03 кг кај женките и околу 14,5 кг кај мажјаците.[4] Лицето е темно розово и има закржлавена опашка, со должина од 4 до 22 мм.[4] Мажјаците почесто имаат подолги опашки. Предните екстремитети на овој мајмун се подолги од задните екстремитети. Женките се помали од мажјаците.[8]

Берберското макаки главно е распострането на падините на венецот Атлас и планината Риф кои се протегаат на териториите на Мароко и Алжир. Станува збор за единствениот вид на макаки кој живее надвор од Азија.[4] Овие животни можат да живеат во различни жиотни средини, како што се кедрови, елови и дабови шуми, како и пасишта, грмушки, каменести предели со растителна вегетација. Повеќето берберски макаки живеат во кедрови шуми во пределот на планината Атлас, сепак, ова само го прикажува моменталното живеалиште, наместо живеалиштето во кое тие го одбрале да живеат.[4]

Исхраната на берберското макаки се состои од мешавина на билки и инсекти.[4] Тие се хранат со бројни голосеменици и скриеносеменици. Се хранат со целото растение, цветови, плод, семиња, никулци, лисје, стебленца, кора, смола, гранки, корења, пупки, и желади.[4] Чест животински плен на берберското макаки се полжавите, црвите, скорпиите, пајаците, стоногалките, многуножци, скакулци, термити, водени дрвеници, тврдокрилци, бумбари, пеперутки, молци, мравки, па дури и со полноглавци.[4]

Нивни грабливци се леопардите, орлите, и домашните кучиња.[4] Приближувањето на орлите или пак домашните кучиња доведува до тоа мајмуните да сигнализираат еден вид на аларм за приближувањето на овие грабливци.[4]

Берберско макаки (науч. Macaca sylvanus) — вид на макаки единствено кое се наоѓа на територија надвор од Азија и има закржлавена опашка. Може да се сретна на падините на планината Атлас во Алжир и Мароко и малубројна популација која била пренесена од Мароко до Гибралтар, берберското макаки е најдобро познат мајмун од Европа species.

Берберското макаки е од интерес бидејќи мажјаците имаат нетипична улога да се грижат за младите. Поради несигурноста наза татковството, мажјаците подеднакво се грижат за сите младенчиња. Општо, Берберските макаки од сите возрасти и пол придонесуваат за грижата на младите.

Исхраната на макикито се содржи претежно од растенија и инсекти во зависност од животната средина. Мажјаците живеат и до 25 години додека пак женките можат да живеат и 30 години. Покрај луѓето, тие се единствените слободни примати во Европа. Иако видот вообичаено се нарекува „Берберски примат“, берберското макаки е всушност вистински мајмун. Неговото име потекнува од Берберското крајбрежје во северозападна Африка.

Берберските макаки кои живеат во Гибралтар се единствената група која живее надвор од Северна Африка и единствените диви мајмуни на тлото на Европа. Во Гибралтар живеат отприлика 230 макаки.

Магот (лат. Macacus sylvanus) — макак маймылдардын бир түрү.

Магот або Бэрбэрыйскі макак (Macaca sylvanus) — адзіная малпа, якая жыве ў дзікім выглядзе на тэрыторыі Эўропы (у Гібральтары). Акрамя таго, магот — адзіная макака, якая жыве не ў Азіі.

Магот — беcхвостая вузканосая малпа. Цела пакрыта густой бура-жоўтай поўсьцю, часта з чырванаватым адценьнем. Рост самцоў даходзіць да 75-80 сантымэтраў, а вага — 13-15 кіляграмаў. Саміцы нашмат драбнейшыя. Да 4-5 гадоў маготы дасягаюць палаваспеласьці, жывуць каля 20 гадоў.

Магот або Бэрбэрыйскі макак (Macaca sylvanus) — адзіная малпа, якая жыве ў дзікім выглядзе на тэрыторыі Эўропы (у Гібральтары). Акрамя таго, магот — адзіная макака, якая жыве не ў Азіі.

Магот — беcхвостая вузканосая малпа. Цела пакрыта густой бура-жоўтай поўсьцю, часта з чырванаватым адценьнем. Рост самцоў даходзіць да 75-80 сантымэтраў, а вага — 13-15 кіляграмаў. Саміцы нашмат драбнейшыя. Да 4-5 гадоў маготы дасягаюць палаваспеласьці, жывуць каля 20 гадоў.

The Barbary macaque (Macaca sylvanus), also known as Barbary ape, is a macaque species native to the Atlas Mountains of Algeria, Libya, Tunisia and Morocco, along with a small introduced population in Gibraltar.[2] It is the type species of the genus Macaca. The species is of particular interest because males play an atypical role in rearing young. Because of uncertain paternity, males are integral to raising all infants. Generally, Barbary macaques of all ages and sexes contribute in alloparental care of young.[5]

The diet of the Barbary macaque consists primarily of plants and insects and they are found in a variety of habitats. Males live to around 25 years old while females may live up to 30 years.[6][7] Besides humans, they are the only free-living primates in Europe. Although the species is commonly referred to as the "Barbary ape", the Barbary macaque is actually a true monkey. Its name refers to the Barbary Coast of Northwest Africa.

The population of the Barbary macaques in Gibraltar is the only one outside Northern Africa and the only population of wild monkeys in Europe. Barbary macaques were once widely distributed in Europe, as far north as England, from the Early Pliocene (Zanclean) to the Late Pleistocene.[8] About 300 macaques live on the Rock of Gibraltar. This population appears to be stable or increasing, while the North African population is declining.[2]

The Barbary macaque is first described in scientific literature by Aristotle in the fourth century BCE work History of Animals. He writes of an ape, "Πίθηκος" (/pɪˈθiːkəs/), with "arms like a man, only covered with hair", "feet [which] are exceptional in kind ... like large hands", and "a tail as small as small can be, just a sort of indication of a tail". It is likely that Galen (129–c.216) dissected the Barbary macaque in the second century CE, presuming the internal structure to be the same as a human. Such was the authority of his work, some mistakes he made were not corrected until Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) proved otherwise over a thousand years later.[9] The Barbary macaque was included in the grouping Simia by Conrad Gessner in his 1551 work Historia Animalium,[9] a name which he claimed was already in use by the Greeks.[10] Gessner's Simia was subsequently used as one of Carl Linnaeus' four primate genera when he published Systema Naturae in 1758. Linnaeus proposed the scientific name Simia sylvanus for the Barbary macaque.[3] During the next 150 years primate taxonomy was subject to great changes and the Barbary macaque was placed in over thirty different taxa.[7] The confusion over the use of Simia became so great that the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) suppressed its use in 1929.[10][7] This meant the Barbary macaque was placed in the next oldest genus assigned to it, Macaca, described by Bernard Germain de Lacépède in 1799.[7]

The Barbary macaque is the most basal macaque species.[11][12] Phylogenetic and molecular analyses show it is a sister group to all Asian macaque species. The results of a phylogenetic analysis show that the chromosomes of Barbary macaque resemble those of the rhesus macaque with the exception of chromosomes 1, 4, 9, and 16. It was also discovered that chromosome 18 in the Barbary macaque is homologous to chromosome 13 in humans.[7]

Polymerase chain reaction studies have found Alu element insertions, small pieces of genetic code in genomes, can infer primate phylogenetic relationships. Using this method the phylogenetic relationship of ten species within the genus Macaca has been resolved, showing the Barbary macaque to be a sister group to all other macaques.[11]

Barbary macaque fossils have been found across Europe, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Black Sea, dating from the Early Pliocene (5.3-3.6 million years ago) to the Late Pleistocene, assigned to various subspecies including M. s. sylvanus, M. s. pliocena and M. s. florentina. The insular dwarf M. majori endemic to Sardinia-Corsica during the Early Pleistocene, usually considered to have derived from M. sylvanus, is generally considered a distinct species. Remains from Norfolk, England, dating to the Middle Pleistocene, at 53 degrees latitude, are amongst the northernmost records of non-human primates. The youngest known remains of Barbary macaques in Europe are from Hunas, Bavaria, Germany, dated to 85-40,000 years ago. The distribution of Barbary macaques in Europe was likely strongly controlled by climate, only extending into Northern Europe during interglacial intervals.[8]

The Barbary macaque has a dark pink face with a pale buff to golden brown to grey pelage and a lighter underside. The colour of mature adults changes with ages.[13][7] In adults and subadults the fur on the back is variegated pale and dark which is due to banding on individual hairs. In spring to early summer, as the temperatures rise, the adult macaques moult their thick winter fur. The species shows sexual dimorphism with males larger than females. The mean head-body length is 55.7 cm (21.9 in) in females and 63.4 cm (25.0 in) in males. The boneless vestigial tail is greatly reduced compared with other macaque species and, if not absent, measures 4–22 mm (0.16–0.87 in). Males may have a more prominent tail, though data is scarce.[7] The average body weight is 9.9–11 kg (22–24 lb) in females and 14.5–16 kg (32–35 lb) in males.[7][14]

Like all Old World monkeys, the Barbary macaque has well-developed sitting pads (ischial callosities) on its rear.[14] Females exhibit an exaggerated anogenital swelling,[15][16] which increases in size during oestrus.[17][18] It has cheek pouches and high-crowned bilophodont molars (molars with two ridges); the third molar is elongated.[14] The diploid chromosome number of the Barbary macaque is 42, like other members of the Old World monkey tribe Papionini.[7]

The Barbary macaque is the only macaque species found outside Asia, and only African primate that survives north of the Sahara Desert.[13][2] It lives mainly in fragmented areas of the Rif and the Middle and High Atlas mountain ranges of Morocco and the Grande and Petite Kabylie mountain region of Algeria. It has been recorded at elevations of 400–2,300 m (1,300–7,500 ft), though it seems to prefer higher elevations. The Moroccan and Algerian populations are around 700 km (430 mi) apart, although the gap was smaller during the Holocene.[7]

The Barbary macaque also occurs in the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar at the southern tip of Europe's Iberian Peninsula. Gibraltar historian Alonso Hernández del Portillo noted in the early 17th century that the macaques had been present "from time immemorial".[19] Most likely, the Moors introduced macaques from North Africa to Gibraltar during the Middle Ages.[20] During World War II, Winston Churchill ordered for more Barbary macaques to be introduced to Gibraltar to reverse population declines.[19] Today, there are around 300 Barbary macaques in Gibraltar.[2]

It can live in a variety of habitats, such as cedar, fir, and oak forests, grasslands, thermophilous scrub, and rocky ridges full of vegetation in Mediterranean climate with seasonal extremes of temperature.[7][13] In Morocco, most Barbary macaques inhabit Atlas cedar (Cedrus atlantica) forests, but this could reflect the present habitat availability rather than a specific preference for this habitat.[7] In Algeria, the Barbary macaque inhabits mainly Grande and Petite Kabylia, ranges that form part of the Tell Atlas mountain chain, but there is also an isolated population in Chréa National Park.[21][2] It lives in mixed cedar and holm oak forests, humid Portuguese and cork oak forests, and scrub-covered gorges.[21]

Fossil evidence indicates the species inhabited southern Europe and all of North Africa. Historically, it occurred across North Africa from Libya to Morocco.[2] A Tunisian population was mentioned in the works of ancient Greek writer Herodotus, indicating the species has become extinct there within the last 2,500 years.[7]

The Barbary macaque is gregarious, forming mixed groups of several females and males. Troops can have 10 to 100 individuals and are matriarchal, with their hierarchy determined by lineage to the lead female.[22] Unlike other macaques, the males participate in rearing the young.[22] Males may spend a considerable amount of time playing with and grooming infants. In this way, a strong social bond is formed between males and juveniles, both the male's own offspring and those of others in the troop. This may be a result of selectivity on the part of the females, who may prefer highly parental males.[5]

The mating season runs from November through March. The gestation period is 147 to 192 days, and females usually have only one offspring per pregnancy. Females rear twins in rare instances. Offspring reach maturity at three to four years of age, and may live for 20 years or more.[23]

Grooming other Barbary macaques leads to lower stress levels for the individuals that do the grooming.[24] While stress levels do not appear to be reduced in animals that are groomed, grooming more individuals leads to even lower stress levels; this is a benefit that might outweigh the costs to the groomer, which include less time to participate in other activities such as foraging. The mechanism for reducing stress may be explained by the social relationships (and support) that are formed by grooming.[24]

Male Barbary macaques interfere in conflicts and form coalitions with other males, usually with related males rather than with unrelated males. These relationships suggest that males do so in order to indirectly increase their own fitness. Furthermore, males form coalitions with closely related kin more often than they do with distantly related kin.[25] These coalitions are not permanent and may change frequently as male ranking within the group changes. Although males are more likely to form coalitions with males who have helped them in the past, this is not as important as relatedness in determining coalitions.[25] Males avoid conflicting with higher ranking males and will more frequently form coalitions with the higher ranking male in a conflict.[25] Close grouping of males occur when infant Barbary macaques are present. Interactions between males are commonly initiated when a male presents an infant macaque to an adult male who is not caring for an infant, or when an unattached male approaches males who are caring for infants. This behaviour leads to a type of social buffering, which reduces the number of antagonistic interactions among males in a group.[22]

An open mouth display by the Barbary macaque is used most commonly by juvenile macaques as a sign of playfulness.[26]

The main purpose of calls in Barbary macaques is to alert other group members to possible dangers such as predators. Barbary macaques can discriminate calls by individuals in their own group from those by individuals in other groups of conspecific macaques. Neither genetic variation nor habitat differences are likely causes of acoustic variation in the calls of different social groups. Instead, minor variations in acoustic structure among groups similar to the vocal accommodation seen in humans are the likely cause. However, acoustic characteristics such as pitch and loudness are varied based on the vocalizations of individuals they associate with, and social situations play a role in the acoustic structure of calls.[27][28]

Barbary macaque females have the ability to recognize their own offspring's calls through a variety of acoustic parameters. Because of this, infant calls do not have to differ dramatically for mothers to be able to recognize their own infant's call. Mothers demonstrate different behaviours on hearing the calls of other infant macaques as opposed to the calls of their own offspring. More parameters for vocalizations lead to more reliable identification of calls in both infants and in adult macaques so it is not surprising that the same acoustic characteristics that are heard in infant calls are also heard in adult calls.[29]

Although Barbary macaques are sexually active at all points during a female's reproductive cycle, male Barbary macaques determine a female's most fertile period by sexual swellings on the female.[30] Mating is most common during a female's most fertile period. The swelling size of the female reaches a maximum around the time of ovulation, suggesting that size helps a male predict when he should mate. This is further supported by the fact that male ejaculation peaks at the same time that female sexual swelling peaks. Change in female sexual behaviour around the time of ovulation is insufficient to demonstrate to the male that the female is fertile. The swellings, therefore, appear necessary for predicting fertility.[18]

Barbary macaque females differ from other nonhuman primates in that they often mate with a majority of the males in their social group. While females are active in choosing sexual associations, the mating behaviour of macaque social groups is not entirely determined by female choice.[30] These multiple matings by females decrease the certainty of paternity of male Barbary macaques and may lead them to care for all infants within the group. For a male to ensure his reproductive success, he must maximize his time spent around the females in the group during their fertile periods. Injuries to male macaques peak during the fertile period, which points to male-male competition as an important determinant of male reproductive success.[30] Not allowing a female to mate with other males, however, would be costly to the male, since doing so would not allow him to mate with more females.[30]

Barbary macaques from all age and sex groups participate in alloparental care of infants. Male care of infants has been of particular interest to research because high levels of care from males are uncommon in groups where paternity is highly uncertain. Males even act as true alloparents of infant macaques by carrying them and caring for them for hours at a time as opposed to just demonstrating more casual interactions with the infants. The social status of females plays a role in female alloparental interactions with infants. Higher-ranking females have more interactions, whereas younger, lower-ranking females have less access to infants.[5]

The diet of the Barbary macaque consists of a mixture of plants and insect prey. It consumes a large variety of gymnosperms and angiosperms. Almost every part of the plant is eaten, including flowers, fruits, seeds, seedlings, leaves, buds, bark, gum, stems, roots, bulbs, and corms. Common prey caught and consumed by Barbary macaques are snails, earthworms, scorpions, spiders, centipedes, millipedes, grasshoppers, termites, water striders, scale insects, beetles, butterflies, moths, ants, and even tadpoles.[7]

Barbary macaques can cause major damage to the trees in their prime habitat, the Atlas cedar forests in Morocco. Since deforestation in Morocco has become a major environmental problem in recent years, research has been conducted to determine the cause of the bark stripping behaviour demonstrated by these macaques. Cedar trees are also vital to this population of Barbary macaques as an area with cedars can support a much higher density of macaques than one without them. A lack of a water source and exclusion of monkeys from water sources are major causes of cedar bark stripping behaviour in Barbary macaques. Density of macaques, however, is less correlated with the behaviour than the other causes considered.[31]

The Barbary macaque's main predators are the domestic dog,[7] leopard and eagles; the golden eagle may only prey on cubs, since it is morphologically not adapted to hunt primates.[32] The approach of eagles and domestic dogs is known to elicit an alarm call response.[7]

Wild populations of Barbary macaques have suffered a major decline in recent years to the point of being declared an endangered species on the IUCN Red List since 2008. The Barbary macaque is threatened by fragmentation and degradation of forest habitat, and poaching for the illegal pet trade; it is also killed in retaliation for raiding crops.[2][33] Today, no accurate data exists on the location and number of individuals out of their natural habitat. An unknown number of individuals are living in zoological collections, at other institutions, in private hands, in quarantine, or waiting to be relocated to appropriate destinations.[2]

The habitat of the Barbary macaque is under threat from increased logging activity.[34] Local farmers regard the Barbary macaque as pest and engage in its extermination. Once common throughout northern Africa and southern Mediterranean Europe, only an estimated 12,000 to 21,000 Barbary macaques are left in Morocco and Algeria. Once, its distribution was much more extensive, spreading east through Algeria, Tunisia and Libya, and north to the United Kingdom. Its range is no longer continuous, with only isolated areas of range remaining. By the Pleistocene, it inhabited the warmer Mediterranean regions of Europe, from the Balearic Islands and mainland Iberia and France in the west, east to Italy, Sicily, Malta, and as far north as Germany and Norfolk in the British Isles.[35] The species decreased with the arrival of the last Last Glacial Period, going functionally extinct on the Iberian Peninsula except for Gibraltar around 30,000 years ago.[36]

The Barbary macaque is threatened by habitat loss, overgrazing, and illegal capture. In Morocco, tourists interact with Barbary macaques in many regions. Information collected in the interviews with inhabitants in the High Atlas of Morocco indicated that the capture of macaques occurs in these regions. Conflict between local people and wild macaques is one of the greatest challenges to Barbary macaque conservation in Morocco. The main threats to the survival of Barbary macaques in this region have been found to be habitat destruction and the impact of livestock grazing, but problems of conflict with inhabitants are also increasing due to crop raiding and the illegal capture of macaques. Human–macaque conflict is mainly due to crop raiding. In the High Atlas of Morocco, macaques attract a large number of tourists every year, and they are favoured for their potential benefits to tourism. In addition, macaques have some ecological roles; for example, they are the predators of several destructive insects and pests of plants and participate in seed dispersal in many plant species.[37][38][39][40][41][42]

In the Central High Atlas, the Barbary macaque occurs in relatively small and fragmented areas restricted to the main valleys at elevations of 700–2,400 m (2,300–7,900 ft). In a 2013 study, researchers reported that they found Barbary macaques in relatively small and fragmented habitats in 10 sites, and that the species no longer occurred in four localities. This could be attributed to habitat degradation, hunting activities, the impact of livestock grazing, and disturbance by people. As deforestation for agriculture and overgrazing continues, the remaining forest becomes increasingly fragmented. Consequently, the Barbary macaque is now restricted to small, fragmented relict habitats.[37]

Many of the mistaken ideas about human anatomy contained in the writings of Galen are apparently due to his use of the Barbary macaque, the only anthropoid available to him, in dissections.[43] Strong cultural taboos of his time prevented his performing any actual dissections of human cadavers, even in his role as physician and teacher of physicians.[44]

Macaques in Morocco are frequently used as photo props, despite their protected status.[45] Tourists are encouraged to take photos with the animals for a fee. Macaques are also sold as pets in Morocco and Algeria, and exported to Europe to be used as pets and fighting monkeys, both in physical marketplaces and online.[45][46]

Tourists interact with wild monkeys across the globe, and in some situations, tourists may be encouraged to feed, photograph, and touch the monkeys. Although tourism has the potential to bring in money towards conservation goals and provides an incentive for the protection of natural habitats, close proximity and interactions with tourists can also have significant psychological impacts on the Barbary macaques. Fecal samples and stress-indicating behaviours, such as belly scratching, indicate that the presence of tourists has a negative impact on the macaques. Human activities such as taking photographs cause the animals stress, possibly because the people come too close to the animals and make prolonged eye contact (a sign of aggression in many primates). Macaques that live in areas close to human contact have more parasites and lower overall health than those that live in wilder environments, at least in part due to the unhealthy diets they receive as a result of feeding from humans.[47][48]

Several groups of Barbary macaques can be found in tourist sites, where they are affected by the presence of visitors providing food to them. Researchers comparing two such groups in the central High Atlas mountains in 2008 found that the tourist group of Barbary macaques spent significantly more time engaged in resting and aggressive behaviour, and foraged and moved significantly less than the wild group. The tourist group spent significantly less time per day feeding on herbs, seeds, and acorns than the wild group. Human food accounted for 26% of the daily feeding records for the tourist group, and 1% for the wild-feeding group.[39] Scientists who collected data on the seasonal activity budget and diet composition of the endangered Barbary macaque group inhabiting a tourist site in Morocco found that activity budgets and diet of the study group varied markedly among seasons and habitats. The percentage of daily time spent in foraging and moving was lowest in spring, and the daily time spent in resting was highest in spring and summer. The time budget devoted to aggressive display was highest in spring than the other three seasons. There is an increase in the daily feeding time spent eating flowers and fruits in summer, seeds, acorns, roots and barks in winter and autumn, herbs in spring and summer, and a clear increase in consumption of the human food in spring.[38] The tourist and the wild groups did not differ in the proportion of daily records devoted to terrestrial feeding, but the tourist group spent a significantly lower percentage of daily records in terrestrial foraging, moving and resting, while performing more terrestrial aggressive displays more than the wild group. There was no significant difference between the two groups in the proportion of terrestrial feeding records spent eating fruits; but the tourist group had lower daily percentages of terrestrial feeding on leaves, seeds and acorns, roots and barks, and herbs, while it spent higher daily percentages of terrestrial feeding on human food.[40]

Barbary macaques were traded or perhaps given as diplomatic gifts as long ago as the Iron Age, as indicated by remains found in such sites as Emain Macha in Ireland, dating to no later than 95 BC; an Iron Age hillfort, the Titelberg in Luxembourg; and two Roman sites in Britain.[49]

The Barbary macaque (Macaca sylvanus), also known as Barbary ape, is a macaque species native to the Atlas Mountains of Algeria, Libya, Tunisia and Morocco, along with a small introduced population in Gibraltar. It is the type species of the genus Macaca. The species is of particular interest because males play an atypical role in rearing young. Because of uncertain paternity, males are integral to raising all infants. Generally, Barbary macaques of all ages and sexes contribute in alloparental care of young.

The diet of the Barbary macaque consists primarily of plants and insects and they are found in a variety of habitats. Males live to around 25 years old while females may live up to 30 years. Besides humans, they are the only free-living primates in Europe. Although the species is commonly referred to as the "Barbary ape", the Barbary macaque is actually a true monkey. Its name refers to the Barbary Coast of Northwest Africa.

The population of the Barbary macaques in Gibraltar is the only one outside Northern Africa and the only population of wild monkeys in Europe. Barbary macaques were once widely distributed in Europe, as far north as England, from the Early Pliocene (Zanclean) to the Late Pleistocene. About 300 macaques live on the Rock of Gibraltar. This population appears to be stable or increasing, while the North African population is declining.

Magoto (Macaca sylvanus) estas senvosta makako, speco de simio. Ĝi troviĝas en la Atlasa Montaro de Alĝerio kaj Maroko kun eta eble enportita loĝantaro en Ĝibraltaro. Krom homoj, magotoj estas la solaj primatoj, kiuj libere vivas en Eŭropo.

Ekzistas legendo, ke Ĝibraltaro restados brita dum magotoj vivas tie. Parte pro tio la makakoj estas sub speciala gardado de la reĝa ŝiparo de Britio.

Magoto (Macaca sylvanus) estas senvosta makako, speco de simio. Ĝi troviĝas en la Atlasa Montaro de Alĝerio kaj Maroko kun eta eble enportita loĝantaro en Ĝibraltaro. Krom homoj, magotoj estas la solaj primatoj, kiuj libere vivas en Eŭropo.

Ekzistas legendo, ke Ĝibraltaro restados brita dum magotoj vivas tie. Parte pro tio la makakoj estas sub speciala gardado de la reĝa ŝiparo de Britio.

El macaco de Berbería (Macaca sylvanus), también llamado mono de Gibraltar y mona rabona, es una especie de primate catarrino de la familia Cercopithecidae que se encuentra actualmente en algunas zonas reducidas de los Montes Atlas del norte de África y en el peñón de Gibraltar, en el sur de la península ibérica. Es el único primate —con excepción de los humanos— que puede encontrarse actualmente en libertad en Europa, y el único miembro del género Macaca que vive fuera de Asia.

Es un cuadrúpedo de escaso tamaño, nunca superior a los 75 cm de longitud y los 13 kg de peso. El cuerpo está recubierto de pelo pardo-amarillento, ligeramente grisáceo en algunos individuos. La cara, pies y manos son de color rosado, y la cola vestigial y poco apreciable a distancia. Los machos son mayores que las hembras.

Los macacos de Berbería son animales diurnos y omnívoros, que viven en bosques mixtos hasta algo más de 2100 metros sobre el nivel del mar. Se mueven constantemente a la búsqueda de frutas, hojas, raíces o insectos, en grupos de entre 10 y 30 individuos de estructura matriarcal dirigidos por una hembra. Tras cuatro o cinco meses de gestación, las hembras paren una cría (dos en casos excepcionales) que son cuidadas tanto por el padre como por la madre. Maduran a los 3 o 4 años de edad y pueden vivir una veintena.

Se estima que la población total es de 1200 a 2000 ejemplares. La especie baja conforme se talan los bosques del Atlas, su hábitat principal, y actualmente se la considera en estado de peligro. Mientras que en el norte de África se la considera casi una alimaña y es perseguida por ello (en gran parte debido a los prejuicios islámicos contra estos monos, reflejados en el Corán), en Gibraltar se considera casi como una mascota no oficial, donde pasea sin inmutarse por los parques y tejados de las casas y es alimentada tanto por las autoridades como los lugareños. El origen de esta población es un misterio, pero parece claro que ha sido introducida. Aunque durante el Pleistoceno hubo momentos en que esta especie habitó en toda Europa (llegando por el norte hasta Alemania e Inglaterra) y las costas mediterráneas, decreció rápidamente con la llegada de las glaciaciones hasta extinguirse en la península ibérica hace unos 30 000 años. Se cree que pudo volver en estado domesticado y luego se asilvestró. En cualquier caso, su presencia en el Peñón está documentada antes de que fuera capturado por los ingleses en 1704.

Como parte del patrimonio de Gibraltar, la alimentación y supervivencia de los macacos ha sido responsabilidad de la Royal Navy hasta que fue cedida al gobierno gibraltareño en 1991. La tradición popular dice que mientras las monas persistan en Gibraltar, este seguirá bajo dominio británico, por lo que se ha llegado al punto de que durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, cuando se temía una posible invasión hispano-germana, el propio primer ministro británico Winston Churchill ordenó traer varias docenas de ejemplares del norte de África para asegurar su exigua población.[cita requerida] Hoy la población de monos ha aumentado, llegando a unos 300 ejemplares.

El macaco de Berbería (Macaca sylvanus), también llamado mono de Gibraltar y mona rabona, es una especie de primate catarrino de la familia Cercopithecidae que se encuentra actualmente en algunas zonas reducidas de los Montes Atlas del norte de África y en el peñón de Gibraltar, en el sur de la península ibérica. Es el único primate —con excepción de los humanos— que puede encontrarse actualmente en libertad en Europa, y el único miembro del género Macaca que vive fuera de Asia.

Magot ehk berberi makaak (Macaca sylvanus) on Põhja-Aafrika Atlase mägedes ja Gibraltari kaljudel karjadena elutsev pärdiklane makaagi perekonnast.

Magot on oma perekonna ainus sabata liik ja ühtlasi ainus ahv, kelle levila ulatub Euroopasse. Osa teadlasi peab Gibraltari asurkonda jäänukiks varasemast laiemalt levinud populatsioonist, osa aga Aafrikast ammusel ajal sissetooduks.

Berberia makakoa edo Gibraltarreko tximua (Macaca sylvanus), Mundu Zaharreko tximua da, eta gaur egun, Atlas mendietako zona konkretuetan eta Gibraltarreko haitzean, Iberiar penintsularen hegoaldean, bizi da. Gizakiaz gain, Europan askatasunean bizi den primate bakarra da, eta Asiatik kanpo bizi den Macaca generoaren animalia bakarra da.

Tamaina txikiko lauoinekoa da, inoiz ez ditu 75 zentimetroko luzera eta 13 kilogramoko pisua gainditzen. Marroi-horixka koloreko ileaz estalita du gorputza, baita kasu batzuetan grisa ere. Aurpegia, oinak eta eskuak arrosa kolorekoak dira. Arrak, emeak baino handiagoak dira. Berberiako tximinoak egunezko animalia orojaleak dira, baso mixtoetan bizi dira, itsas mailatik 2.100 metroraino.

Gaur egun munduan 1200-2000 inguruko berberiar makako gelditzen dira. Espeziearen habitat nagusia Atlas mendietan dago. Egoera ahulean bezala sailkatuta dago. Afrikako iparraldean, orokorrean, piztia bezala dago ikusita, batez ere Islamaren aurreiritzien ondorioz zeren eta, Koranen jasotzen den bezala, tximuak beti mespretxuz tratatuak izan baitira. Bestealdetik animalien trafikatzaileek talde askorekin bukatu dute eta espeziaren etorkizuna arriskuan jarri dute.[1] Gizakien jasarkundetik kanpo, desforestazioa da espezieak pairatzen duen arazo nagusia.

Gibralatarren, bestetik, beste populazio finkoa dago baina han egoera oso desberdina da. Makakoak oso apreziatuak dira eta ia lurraldearen ikus ezofiziala dira. Inguru horretan jendearekin bizitzen ohitu dira eta herrian zehar problemarik gabe mugitzen dira, turistentzat benetako erreklamoa izanik. Multzo honen jatorria benetako misterioa da baina, itxura guztien arabera, berandu sartuak izan ziren nahiz eta espezie hau Pleistozenoan zenbait momentutan espeziea Europa osoan zabaldu izan;animalia hauen aztarnak, besteak beste, Alemanian eta Ingalaterran aurkitu izan dira. Makako hauen kopurua erabat jaitsi zen glaziazioen ondorioz. Iberiar Penintsulan 30.000 urte dira erabat desagertu zela. Gibraltarren, antza denez, domestikatuta itzuliko zen eta, gero, basatu egin zen. Dena dela, haien presentzia haitza ingelesen etorreraren aurrekoa da, hau da, 1704 baino aurrekoa. Gaur egun makako honen Gibraltarreko taldea, 300 animalien ingurukoa, Europako bakarra da.

Barberiar makakoa Gibraltarreko ondarearen partea da gaur egun. Hasiera batean haien babesa eta mantenimendua Royal Navyren ardura zen. 1991an lan hori Gibraltarreko gobernuaren esku gelditu zen. Herriaren tradizioaren arabera, makakoak haitzan dauden bitartean hau britaniarren esku egongo da. Kondaira hori zela eta, Bigarren Mundu Gerran, alemaniarren eta espainiarren inbasioaren beldurrez Winston Churchill lehen ministroak Afrikatik eramandako animaliekin bertako populazioa indartzeko agindua eman zuen.

Berberia makakoa edo Gibraltarreko tximua (Macaca sylvanus), Mundu Zaharreko tximua da, eta gaur egun, Atlas mendietako zona konkretuetan eta Gibraltarreko haitzean, Iberiar penintsularen hegoaldean, bizi da. Gizakiaz gain, Europan askatasunean bizi den primate bakarra da, eta Asiatik kanpo bizi den Macaca generoaren animalia bakarra da.

Magotti eli berberiapina (Macaca sylvanus) on Pohjois-Afrikassa ja Gibraltarilla elävä makakien sukuun kuuluva apinalaji. Se on Euroopan ainoa luonnonvarainen apinalaji ihmisen lisäksi.

Magotti on noin 70-senttinen ja 8–10 kilon painoinen. Magotin häntä on lähes näkymätön, 1–2 sentin nypykkä. Turkki antaa vantteran olemuksen, vaikka se on melko lyhytkarvainen. Lajin raajat ovat tanakat ja sen pää on iso. Magotilla on isot pakarat, jotka ovat lisääntymisaikana voimakkaan väriset. Turkki on väriltään ruskehtava, selän ja raajojen turkki on kellertävänruskea tai ruskehtavanharmaa. Pää on tummempi ja vatsapuoli on vaalea.

Magotteja elää Pohjois-Afrikan Marokossa ja Algeriassa, joissa elää yhteensä noin 10 000 yksilöä, eniten Marokossa. Lisäksi Espanjan eteläpuolella Gibraltarin niemellä elää noin 200 puolivillin yksikön kanta[2]. Magotteja on aikoinaan elänyt Euroopassa myös pohjoisemmassa, jopa Keski-Saksassa ja Irlannissa saakka[2].

Ennen magotteja eli myös Libyassa ja Egyptissä. Mahdollisesti levinneisyys on ulottunut myös Aasiaan asti.

Magotit elävät Pohjois-Afrikassa enimmäkseen Atlasvuoriston mänty-, tammi-, ja setrimetsissä 2 100 metrin korkeuteen asti. Alueella sataa joka vuosi lunta. Laji elää myös pensaikko- ja kalliomailla. Koska muutamia yhteisöjä elää myös alavilla mailla, magottien on ajateltu eläneen aiemmin tasangoillakin. Lisääntyvän asutuksen takia ne olisivat säilyneet lähinnä vuorilla. Gibraltarin apinat elävät kahdenlaisessa ympäristössä, merenrantakallioilla ja kaupunkiympäristössä.

Magotit elävät 7–40 yksilön laumoina. Naaraat pysyvät synnyinlaumassa koko ikänsä, mutta koiraat lähtevät etsimään aikuistuttuaan uutta laumaa. Magotit ovat hyvin sosiaalisia ja rauhallisia apinoita. Naaraat antavat usein turvallisiksi tuntevansa uroksen hoitaa poikastaan ja koiraat käyttävät niitä joskus puskureina muita uroksia vastaan. Laumassa on tarkka arvojärjestys. Magotit tyytyvät varsin vähään ja syövät jopa puun kaarnaa. Tavallisempaa ravintoa ovat kuitenkin siemenet, hedelmät ja lehdet. Eläinravintoa ne syövät harvoin, mutta pitävät erityisesti muurahaisen munista. Poikaset syntyvät heinä-elokuussa vajaan puolen vuoden kantoajan jälkeen. Poikasia tulee yksi kerrallaan. Magotit voivat elää yli 20 vuotta.

Magottien elintila on vuosisatojen aikana kaventunut metsien hakkuun ja metsästyksen vuoksi. Alueen metsiä on hakattu jo Rooman valtakunnan ajoilta asti ja maanviljely ja karjanhoito alueella on aloitettu heti arabien tulon jälkeen. Karja estää usein puiden taimien kasvun, jos niitä on suurina määrinä.

Nykyään magottien suurin uhka on laiton kauppa. Viimeisen kolmenkymmenen vuoden aikana kanta on puolittunut ja laji on uhanalainen. Vuosittain noin 300 apinanpoikasta myydään laittomasti lemmikeiksi ja sirkuksiin. Niitä käytetään hyväksi myös turistikohteissa, missä niitä kuvautetaan maksusta turistin kanssa[2].

1950-luvulla Gibraltarilla lajia oli joskus jopa liikaakin. Toisen maailmansodan aikana Winston Churchill määräsi, että apinoita on tuotava Afrikasta lisää, koska vanhan tarun mukaan englantilaiset joutuvat luopumaan Gibraltarista, jos magotit häviävät.Lähteet Viitteet

Aiheesta muualla

![]() Kuvia tai muita tiedostoja aiheesta Magotti Wikimedia Commonsissa

Kuvia tai muita tiedostoja aiheesta Magotti Wikimedia Commonsissa

Magotti eli berberiapina (Macaca sylvanus) on Pohjois-Afrikassa ja Gibraltarilla elävä makakien sukuun kuuluva apinalaji. Se on Euroopan ainoa luonnonvarainen apinalaji ihmisen lisäksi.

Macaca sylvanus • Magot

Le macaque de Barbarie (Macaca sylvanus), également appelé magot ou macaque berbère, est un singe catarhinien de la famille des cercopithécidés.

Il est le seul macaque vivant sur le continent africain, à l'état sauvage dans les forêts relictuelles du Maroc et de l'Algérie, ainsi que sur le rocher de Gibraltar, où il a été introduit il y a plusieurs siècles et représente avec l'humain (Homo sapiens) le seul primate d'Europe en liberté[1].

Les autres espèces du genre Macaca vivant principalement en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est, il est considéré comme l'une des formes ancestrales du rameau des macaques qui sont apparus en Afrique il y a 5,5 millions d'années. Néanmoins, sa morphologie et son écologie témoignent d'une réelle adaptation aux conditions de vie dans l'Atlas au Maghreb et donc, bien que l'espèce soit toujours restée sur le continent des origines, elle diffère grandement des premiers macaques apparus.

L'espèce figure sur la liste rouge des espèces menacées d'extinction. Complètement disparue en Tunisie, elle est en déclin en Algérie et au Maroc[2].

Le pelage est de couleur ocre-fauve à presque noir, selon la saison et les individus. De manière générale la face ventrale est beaucoup plus claire que la face dorsale et l'extrémité des membres plus foncés. Le faciès est glabre et peut présenter une grande variété de taches et de pigmentation selon les individus.

Le macaque berbère présente un certain nombre d'adaptations morphologiques au froid liées à l'environnement montagnard où il vit, tempéré l'été et rigoureux l'hiver. De telles adaptations sont rares chez les primates et témoignent de la grande faculté d'adaptation des macaques, puisqu'on en connaît un autre exemple fameux avec le macaque japonais (Macaca fuscata), capable de survivre dans une épaisse neige. Les adaptations morphologiques du magot sont une réduction de la longueur de la queue et des doigts sur les quatre membres (qui pourraient geler s'ils étaient plus longs, la queue est, elle, quasi inexistante), un allongement relatif de la longueur de la colonne vertébrale par rapport aux membres (qui permet de maintenir la température du corps grâce à une posture en boule lors de la recherche alimentaire) et bien sûr d'un fort épaississement du pelage en saison froide.

Comme chez tous les macaques, les mâles sont plus lourds et plus puissants que les femelles, présentent un dimorphisme sexuel quant à la longueur des canines et ne restent pas toute leur vie dans le groupe social où ils sont nés. À l'inverse, les femelles demeurent toute leur vie au sein de leur groupe de naissance sauf en cas de scission du groupe en plusieurs sous-groupes.

À l'état sauvage, les groupes comportent de 12 à 59 individus avec une valeur médiane de 24. Chaque membre du groupe tient une position hiérarchique particulière dans l'échelle de dominance sociale du groupe. Bien que les femelles magots étudiées en semi-liberté soient capables de dominer les femelles plus âgées de lignées maternelles de rang moins élevé (système matrilinéaire classique d'acquisition du rang de dominance), elles ne le font pas systématiquement, voire rarement, par rapport à leurs propres sœurs plus âgées comme c'est le cas chez les femelles macaque rhésus Macaca mulatta ou macaque japonais Macaca fuscata élevées dans des conditions similaires. Ceci est dû à une différence de soutien reçu lors des conflits pouvant opposer les jeunes sœurs à leurs aînées. En effet, les jeunes femelles macaques berbères, si elles reçoivent autant de soutien de la part des individus apparentés, en reçoivent beaucoup moins de la part des membres non apparentés dans de tels conflits que chez les macaques rhésus ou japonais. Il en résulte que chez le macaque berbère au sein d'une lignée maternelle, les femelles le plus âgées sont les plus dominantes alors que c'est le contraire chez les deux autres espèces de macaque mentionnées.

La migration des mâles a été bien documentée pour cette espèce. La plupart des migrations depuis le groupe natal vers un autre groupe ont lieu entre 5 et 8 ans, autour du moment de la puberté, mais, dans les groupes étudiés, seulement un tiers de l'ensemble des mâles effectuent cette migration. Le transfert a lieu principalement lors de la saison de reproduction d'octobre à décembre où ils cherchent d'emblée à interagir avec des femelles en œstrus. Une seconde migration dans la vie d'un individu est possible mais rare. Tous les mâles migrants rejoignent un autre groupe social et ne transitent pas par un groupe de mâles ni ne demeurent solitaires comme c'est parfois le cas chez d'autres macaques. Les taux de migration sont plus hauts lorsque le ratio des individus adultes par rapport à l'ensemble du groupe est élevé.

Les migrants ont une forte préférence pour les groupes sociaux où le nombre de mâles de leur âge est moins élevé que dans leur groupe natal, voire nul. Les études montrent que c'est plus l'évitement de la consanguinité que la compétition entre mâles qui est le moteur de ces migrations, car ce ne sont généralement pas des mâles dominés qui migrent ; par contre, les migrants ont souvent beaucoup de sœurs ou de femelles apparentées dans le groupe d'origine. Les mâles sans femelles apparentées n'émigrent quasiment jamais, et aucun indice ne prouve que les mâles migrants soient écartés du groupe par les autres membres. Le taux de mortalité n'est pas plus important parmi les migrants que chez les autres mâles. Le succès reproductif des migrants est similaire à celui des mâles natifs. La scission du groupe est une autre solution pour éviter la consanguinité, les mâles choisissant plus volontiers le sous-groupe comportant le moins de femelles apparentées.