pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

As in all snakes, African rock pythons have a well-developed vomeronasal (Jacobson's) organ system, supplied by the tongue. This allows perception of chemicals (odors) in the environment, such as prey odors and pheromones produced by other pythons. Pythons also possess heat-sensing pits in the labial scales that detect infrared (heat) patterns given off by endothermic predators and prey.

Communication Channels: visual ; tactile ; chemical

Other Communication Modes: pheromones ; scent marks

Perception Channels: visual ; infrared/heat ; tactile ; acoustic ; vibrations ; chemical

African rock pythons are no longer as widespread as they once were. Python natalensis is now restricted mainly to hunting reserves, national parks and secluded sections of the African savannah. Reduction in available prey animals and hunting for its meat and skin has caused this species to decline in numbers over the years. Larger individuals are increasingly rare in many areas. African rock pythons have been placed on Appendix II of CITES and are legally protected in certain countries where populations have become increasingly vulnerable (such as South Africa).

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: appendix ii

African rock python eggs are laid in hollows and protected by the coils of their mother during development. Once the young hatch they are independent.

These snakes sometimes will feed on livestock and pets of local human residents, particularly if natural prey has become scarce. In the past, rock pythons have been observed feeding on dogs, goats, poultry and other livestock that are important to the livelihood of the native peoples.

African rock pythons can also be a danger to humans. Although it is rare that a python will attack without provocation, there are several reports of rock python attacks on humans. Often, a human will startle a snake, causing it to bite. More rarely, the python may even constrict a human to death, and smaller humans have been eaten in extremely unusual circumstances. Although people are occasionally killed by pythons, the pythons are not always killed in retaliation. The offending snake may be transported to a different area where it is less likely to come into contact with humans.

Negative Impacts: injures humans (bites or stings)

Humans exploit Python natalensis in a number of ways. The most lucrative use is its skin and meat. The skin especially is highly desired by consumers, with the number of skins exported reaching near 9,300 in 2002. Humans also attempt to make pets out of African rock pythons. While a captive born python may be docile if accustomed to handling, wild-caught individuals do not make good pets because of their aggression. Another benefit provided to humans comes from juvenile snakes. Since younger African rock pythons eat rats, they help to control pests in areas of human habitation. Pythons are venerated and protected in some cultures.

Positive Impacts: pet trade ; food ; body parts are source of valuable material; controls pest population

These snakes are predators on small to moderately large vertebrates. As ectotherms, they feed infrequently compared to endothermic predators (such as mammalian predators), and over-all effects on prey populations are presumably minimal in comparison.

Juvenile pythons are prey for numerous predators; adults are much less vulnerable but are occasionally killed by larger mammals.

African rock pythons are carnivores and feed primarily on terrestrial vertebrates. As juveniles, these pythons feed on small mammals, especially rats. Once adult sized, they will move onto larger prey, such as monkeys, crocodiles, large lizards, and antelope. They will sometimes take fish as well. If African rock pythons live near humans, family pets and livestock may be eaten.

African rock pythons generally hunt at twilight using their heat-sensing pits. Once a prey item has been found, the python will sit patiently or move slowly toward the prey. Once in range, the python will strike with devastating speed and accuracy, sinking its long curved teeth into the prey's flesh and coiling around it. The power of these snakes is incredible. A large adult snake can tackle an antelope weighing up to 59 kg.

African rock pythons constrict their prey as do other members of the family Boidae (boas, pythons and anacondas). Contrary to popular belief, large constricting snakes do not crush their prey to death, but rather asphyxiate or compress them until they die of cardiovascular shock. As the prey breathes out, the snake tightens its coils so that the prey cannot breathe in again. Eventually, the prey suffocates or expires from heart failure and is swallowed whole. These snakes can go long periods of time between meals if necessary. A captive specimen reportedly fasted for over 2.5 years.

Animal Foods: birds; mammals; reptiles; fish

Primary Diet: carnivore (Eats terrestrial vertebrates)

African rock pythons occur throughout sub-Saharan Africa, although they avoid the driest deserts and the coolest mountain elevations. Two subspecies are recognized: Python sebae sebae, northern African rock pythons, and Python natalensis, southern African rock pythons. The northern subspecies is found from south of the Sahara to northern Angola, and from Senegal to Ethiopia and Somalia. The southern subspecies is found from Kenya, Zaire and Zambia south to the Cape of Good Hope. The two subspecies overlap in some areas of Kenya and northern Tanzania. Some authorities recognize them as full species, P. sebae and P. natalensis.

Biogeographic Regions: ethiopian (Native )

African rock pythons prefer evergreen forests or moist, open savannahs. These snakes often frequent rocky outcrops that can be utilized for hiding purposes, or they may use mammal burrows in less rocky areas. African rock pythons reportedly have a close association with water and often are found near rivers and lakes. The highest elevation at which an African rock python was observed is 2300 meters, although most pythons are found well below that elevation.

Range elevation: 0 to 2300 m.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; tropical ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: savanna or grassland ; forest

Other Habitat Features: riparian

African rock pythons can live for up to 30 years in captivity.

Range lifespan

Status: captivity: 30 (high) years.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 18.0 years.

Average lifespan

Sex: female

Status: captivity: 27.3 years.

The largest snake in Africa, Python natalensis averages 3 to 5 m in length. There are reports of much larger African rock pythons, including a record from the Ivory Coast of a 7.5 m specimen, and a questionable report of another individual from the same country reaching a length of 9.8 m. Hatchlings are approximately 35 to 45 cm in length. As adults, African rock pythons average 44 to 55 kg in weight, with reports of some reaching well over 91 kg (200 lbs).

African rock pythons have a relatively small, triangular head that is covered in irregular scales that are typically blackish to brownish-gray in color. The head also has two light-colored bands that form a spearhead shape from the snout to the back of the head just above the eyes, as well as a yellow, inverted V under each eye. There are two heat-sensing pits on the supralabial scales on the upper lip and four to six more pits on the infralabial scales. The body is yellowish, gray-brown, or gray-green, with dark blotches that form a staircase-like pattern on the back. Belly scales are a white color with black specks producing a salt-and-peppery pattern. On the tip of the tail, there are two dark bands that are separated by a lighter band. Juveniles are more brightly marked than adults.

It has been noted that individuals found in the central and western parts of Africa are somewhat more brightly marked than their northern, eastern and southern counterparts. Of the two subspecies, P. s. sebae, of northern and western Africa, is generally larger, has larger head scales, and is more brightly colored than P. s. natalensis.

Range mass: 44 to 91 kg.

Average mass: 55 kg.

Range length: 4 to 7.5 m.

Other Physical Features: heterothermic

Sexual Dimorphism: female larger

Aside from humans, adult African rock pythons have few natural predators due to their large size. However, during long digestion periods a python may become vulnerable to predation by hyenas or African wild dogs.

Juveniles are probably subject to attack by more predators.

Known Predators:

Anti-predator Adaptations: cryptic

Some authors have reported large, seasonal congregations of African rock pythons and have suggested that these are mating aggregations, but little is known about mating in the wild.

Male and female African rock pythons reach sexual maturity at three to five years of age. Males will begin breeding at a size of 1.8 m, while females will wait until they have exceeded at least 2.7 m. Breeding usually takes place between November and March. Declining temperature and changing photoperiod act as signals for snakes to begin breeding. During the breeding season, both males and females cease feeding, with females continuing to fast until the eggs hatch. The female lays her eggs about three months after copulation. Clutches are, on average, 20 to 50 eggs in number, although a large female can lay as many as 100 eggs in a single clutch. The eggs are quite large, often weighing 130 to 170 grams, and about 100 mm in diameter.

Breeding interval: African rock pythons breed once yearly.

Breeding season: Breeding usually takes place between November and March.

Range number of offspring: 20 to 100.

Average number of offspring: 20-50.

Range gestation period: 65 to 80 days.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 3 to 5 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 3 to 5 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; sexual ; oviparous

The female will lay her eggs in a tree hollow, termite nest or mammal burrow and coil around them. This coiling behavior may be largely for protection, as the female does not "shiver" to create extra heat for incubation as reported for some other python species. However, a Cameroon specimen had a body temperature 6.5 degrees C higher than ambient temperature. Desired incubation temperature is 31 to 32 degrees C (88 to 90 degrees F). In 65 to 80 days the eggs will hatch, at which time the female will leave the young to fend for themselves. Hatchlings average 450 to 600 mm in length.

Parental Investment: pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female)

Die Afrika-rotsluislang (Python sebae) is 'n slangsoort van die familie luislange (Pythonidae) en word by die genus egte luislange (Python) ingedeel. Hy verskil wat velpatroon en skubbe betref van die Suider-Afrikaanse luislang. Met 'n bevestigde lengte van meer as vyf meter is die Afrika-rotsluislang een van die grootste slange ter wêreld. Sy verspreidingsgebied strek in Afrika besuide die Sahara van die weskus tot die ooskus en suidwaarts tot in die noorde van Angola. Hier woon hy in 'n verskeidenheid tropiese en subtropiese landskappe nooit te ver van water nie. Hy is baie aanpasbaar en bewoon as kultuurvolger[1] ook landbougrond en nedersettings.

Die dieet bestaan uit 'n verskeidenheid gewerwelde diere. In die gebiede met 'n hoë aantal soogdiere, vreet groot individue heel dikwels wildsbokkies wat selde meer as 30 kilogram weeg.

Die jong, onvolgroeide slange is baie slank gebou, maar ontwikkel met toenemende ouderdom 'n baie kragtige lyf. By groot volwasse rotsluislange word die silindriese lyf tot 'n geringe mate afgeplat. Die breë, driehoekige, effens afgeplatte en groot kop is duidelik van die nek onderskeibaar. Die snoet is op die bokant teen die punt toe afgerond. Hier sit die neusgate skuins tussen die bo- en die sykante van die kop. Die spitstoelopende grypstert maak by die wyfies tussen 9 en 14 % en by die mannetjies tussen 11 en 16% van hul totale lengte uit.

Die gebit bestaan uit dun, langwerpige tande wat deurgaans skerp en na die keel teruggebuig is en van die snoet na die keel toenemend kleiner word. Teen die middel van die boonste mondholte loop voor op die bokaak die verhemeltebeen en verder agtertoe die vlerkbeen parallel met mekaar. Simmetriesgesproke is daar aan elke kant 2 tussenkaaksbeen-, 13 tot 16 bokaak-, 6 tot 7 verhemeltebeen-, 8 tot 9 vlerkbeen- en 13 tot 17 onderkaaktande.[2] Die slang het dus altesaam tussen 84 en 102 tande.

By slange word na skubbe dikwels as skilde verwys. 'n Skild is 'n skub met 'n spesiale beskermende funksie.[3]

Die bokant van die kop is kenmerkend met groot skilde bedek: die nasale skilde (neusskilde) word deur een paar vierkantige internasale skilde (tussenneusskilde) van mekaar geskei. Die aangrensende opvallend uitgeboude paar prefontale skilde (voor-voorhoofskilde) word deur 'n ry minder, onreëlmatige skilde agter die volgende groot paar frontale skilde (voorhoofskilde) geskei. Die laasgenoemde paar kan soms gedeeltelik of heeltemal saamgesmelt wees. Die supraokulêre skilde (bo-oogse skilde) is groot en geskei in twee dele. Van die kant af is tussen die oog en neusgat minstens drie tot vier loreale skilde (leiselsskilde) van verskillende groottes asook twee preokulêre skilde (vooroogskilde), waarvan die onderste klein en onreëlmatig gevorm is. Daar is weerskante twee tot vier postokulêre skilde (agteroogskilde). Die rostrale skild (snoetskild) het, soos by die meeste ander luislange, twee diep labiaalgroewe (lipholtes). Van die 13 tot 16 supralabiale skilde (bolipskilde) is die tweede en derde voorstes van fyn lipgroewe of lipkuiltjies voorsien. Die 19 tot 25 infralabiale skilde (onderlipskilde) raak na die snoetpunt se kant toenemend kleiner. Die twee voorstes en die drie tot vier agterstes is met fyn lipkuiltjies bedek.[4] Die aantal ventrale skilde (pensskubbe) wissel na gelang van die individu tussen 265 en 283; die aantal rugskildrye in die middellyf is gewoonlik tussen 76 en 98. Vanaf die kloaak tot by die stertpunt kan 62 tot 76 pare subkoudale skilde (onderstertskubbe) gevind word.[5] Die anale skild kan heel of verdeel wees.[4]

Die grondkleur wissel van geel, beige, ligbruin tot grys.[4] Op die rug loop groot, onreëlmatige, uiterlike bruin rugvlekke wat verskil van individu tot individu. Hulle is swartrandig en word rondom geskei deur 'n breë, ligte gaping van die grondkleur. Op die flanke het die rugvlekke gedeeltelik lengteverbindinge met mekaar en sluit so baie groot, uitgestrekte, helder dele op die rug in.[5] Op die flanke loop, variërend na rugpatroon, bruin, vierkantige vlekke met 'n helder middelpunt. Op die agterlyf word die flankvlekke toenemend dunner en versmelt dikwels met die rugvlekke.[4] By die meeste slange bly daar tussen die donker patroon van die stertbokant in die middel 'n lang, ligbruin streepvormige gedeelte oop. Die pens is gryserig tot gelerig en met donker kolle bedek.[5]

Die kop is kenmerkend kontrasterend van kleur. Op die kante van die kop by die meeste slange loop 'n ligte streep vanaf die onderhelfte van die neus skuins agtertoe na die tweede bolipskild. Dan volg 'n helder donker vlek tussen die oog en neus. Daarna word twee wit bande onder die oog getrek na die bolip en omsluit in die middel 'n donker driehoek. Agter die oog tot by die mondhoek loop 'n donkerbruin streep wat kenmerkend helderder as by die oogdeursnit is. Die bokant van die kop het 'n pylvormige, bruin patroon, wat van die neus oor die oog tot by die nek loop en in die middel 'n ligte vlek vertoon. Die onderlip het meestal donker vlekke. Die res van die onderkant van die kop is wit, maar net agter die keel grens sterk, donker vlekke van die keelonderkant. In die bruinerige iris is die swart pupil duidelik sigbaar.[5]

Die Afrika-rotsluislang word gemiddeld tussen 2,7 en 4,6 meter lank.[6] Dit word bevestig deur 'n studie in Suidoos-Nigerië, waar die gemiddelde kop-romplengte van 39 uitgegroeide mannetjies gemiddeld 2,47 meter was. Die 51 ondersoekte volwasse wyfies was, met 'n gemiddelde kop-romplengte van 4,15 meter, aansienlik langer. Die grootste was omtrent 5 meter lank.[7] Gestaafde gegewens oor die maksimum liggaamslengte van hierdie soort bestaan nie. Volgens Villiers (1950) is daar glo in 1932 in Bingerville aan die Ivoorkus 'n individu van 9,8 meter geskiet.[8] Volgens Branch (1984)[9] en Sprawls et al. (2002)[10] is dit 'n onbetroubare en ongeloofwaardige oorlewering. Daarbenewens is daar ander ongegronde uitsprake van luislange wat oor die 7 meter lank is. In die verlede is massiewe uitgerekte slangvelle herhaaldelik by optekening gebruik, wat die historiese syfers onakkuraat maak. So het Loveridge (1927)[11] in Oos-Afrika 'n 9,1 meter lange slangvel gemeet. Hoewel hierdie vel moontlik met meer as 'n kwart verrek is, kon dit tog oorspronklik dié van 'n 6,5 m-lange Afrika-rotsluislang gewees het.[12] Die langste Afrika-rotsluislang wat tot dusver wetenskaplik korrek opgeteken is, is uit Uganda afkomstig. Dit was, volgens Pitman (1974), gesamentlik 5,5 meter (18 vt.) lank.[6]

Die verspreidingsgebied van die Afrika-rotsluislang wissel suid van die Sahara vanaf die Wes-Afrikaanse kuste ooswaarts oor 6 600 kilometer amper tot by die sogenaamde Horing van Afrika. In Wes-Afrika word die spesie in Suid-Mauritanië,[13] Senegal, Gambië, Guinee-Bissau, Guinee, Sierra Leone, Liberië, die Ivoorkus, Suid-Mali, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Suid-Niger en Nigerië aangetref. In Sentraal-Afrika is hul tuis in Suid-Tsjad, in Kameroen, die Sentraal-Afrikaanse Republiek, Ekwatoriaal-Guinee, Gaboen, die Republiek van die Kongo, die Demokratiese Republiek van die Kongo en Noord-Angola. In die ooste kry mens hierdie luislang in Suid-Soedan, in Etiopië, Somalië, Kenia, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi en Tanzanië.[5]

Daar word vermoed dat die Suider-Afrikaanse luislang eens noordwaarts al langs die westelike en oostelike valleie van die Groot Skeurvallei versprei het waar Python sebae oorheersend is.[14] In Kenia is daar 40 km noordwes van Mwingi vandag nog 'n gebied waar die twee luislangspesies se habitats oorvleuel. Ook in Burundi en in die ooste van die Kivuprovinsie van die Demokratiese Republiek van die Kongo bestaan daar nog oorblywende bevolkings. In Tanzanië oorvleuel die verspreidingsgebiede van beide spesies oor 'n ruim 900 kilometer.[14] Vorige ondersoeke in Angola toon 'n volledig ruimtelike skeiding van al twee spesies.[5]

Die Afrika-rotsluislang is woonagtig in verskeie onderskeie habitats in die trope en subtrope, waaronder wortelboomwoude, oerwoude, permanent oorstroomde moeraswoude, sekondêre moeraswoude,[15] digte en oop droëwoude,[2] grasland en sandvlaktes. As kultuurvolger bewoon hy ook dikwels kassawe-, pynappel-, patat- en oliepalmplantasies asook landerye. Heel dikwels kan hy ook relatief onopsigtelik in die buitewyke van nedersettings woon. Die slang hou altyd naby water en bewoon daarom meestal gebiede langs permanente damme(tjies), mere, spruitjies, riviere en soms ook brakwater.[7] In Suid-Mauritanië woon hy egter ook in vleilande waar water jaarliks heeltemal opdroog en dan net 'n paar kolletjies oewerplantegroei as skuilplek bied.[13] Hierdie slang vermy baie vogtige gebiede. So is hierdie spesie in die reënwoud maar skaars te vinde.[16] In Rwanda kan die slangsoort se habitat hoogtes van meer as 1 350 meter bo seespieël bereik en in Uganda is hul al selfs op 2 250 meter bo seespieël aangeteken. In Kenia en Noord-Tanzanië, waar die Afrika-rotsluislang en die Suider-Afrikaanse luislang se verspreidingsgebiede oorvleuel, is die Afrika-rotsluislang hoofsaaklik in die laer dele teenwoordig.[5]

Die Afrika-rotsluislang is oorwegend grondbewonend en kan hom hier selfs as volgroeide slang nog taamlik vinnig[6] voortbeweeg. As bobaas-klimdier hou hy ook gereeld in bome om te jag of roofvyande te ontwyk. Veral jong en onvolgroeide Afrika-rotsluislange met 'n liggaamslengte van onder 1,8 meter is dikwels in bome en struike te vinde. Volgroeide slange word as minder gereelde klimmers beskou. Volgroeide luislange met 'n totale lengte van meer as 2,5 meter is goeie swemmers en bring dikwels lang tye in die water deur. Inligting oor die jong luislange se deurbring in die water ontbreek.[7] By die Victoriameer lê hierdie luislange soms aansienlike afstande af deur tussen die eilande en die vasteland te swem en terug.[6] Verder is hy waarskynlik ook in staat om selfs in die see enkele kilometers swemmend af te lê. Dit verklaar byvoorbeeld die aanwesigheid van die slangsoort op die nabygeleë Chula-eiland van die Bajuni-eilande in Suid-Somalië.[2] In Uganda word die water veral gedurende die warm dae van die droë seisoen benut om die lyf in vlak water af te koel, met net die neusgate en oë wat bo die wateroppervlakte uitsteek.[6] Riviere en spruitjies word ook deur hierdie slang benut om bewoonde gebiede binne te dring, op soek na kos. Die water word daarmee beskou as die beginpunt om voedsel te soek en as veilige skuilplek vir die slang om heen te vlug.[7]

In gebiede soos Suidoos-Nigerië, waar die klimaat onderhewig is aan seisoensveranderinge, toon die spesie deur die jaar heen wisselende aktiwiteitspatrone. Die slang word op sy aktiefste gedurende die droëtyd in Januarie en tydens die laaste fase van die reëntyd vanaf Augustus tot September waargeneem.[7] In die lande aan die ewenaar geleë, by name Kenia en Uganda, word hierdie luislange as oorwegend skemer- en nagdiere beskryf, maar kan by geleentheid ook bedags waargeneem word wanneer hulle in die son bak of kos soek.[6][10] 'n Noukeurige ondersoek in sommige noordelike dele van Suidoos-Nigerië het geblyk dat die Afrika-rotsluislang in gebiede afgesonder van mense hoofsaaklik dagdiere is. Die meeste slange word hier in die namiddag tussen 15:00 tot 17:30 waargeneem. In digbeboste gebiede, veral langs spruite en riviere, is die luislangspesie van vroegoggend tot die middag op sy bedrywigste. In teenstelling hiermee is die Afrika-rotsluislange wat in die nabyheid van menslike nedersettings en stedelike gebiede voorkom oorwegend skemer- en nagdiere; hulle is op hul bedrywigste teen aandskemering.[7]

Tydens die onaktiewe fases soek hierdie luislange wegkruipplekke, byvoorbeeld in digte bosse, oewerplantegroei, water, bome, rotsskeure, hol boomstamme[16] en verlate gate van vlakvarke, erdvarke[2] of ystervarke. Hier krul die slang hom gewoonlik in 'n bondel op, met sy kop wat heeltemal bo-op rus.[10]

Inligting omtrent die beweegruimte en habitatwisseling is tot dusver slegs by een individu in Suidwes-Kameroen opgeteken. Oor meer as 'n jaar heen is 'n wyfie met 'n kop-romplengte van 2,4 meter en 'n massa van 3,7 kilogram deur middel van 'n opspoortoestel waargeneem. Hierdie dier het hoofsaaklik binne 'n kerngebied van 2,4 hektaar beweeg, meestal nooit verder as 10 meter van water nie en het dikwels en herhaaldelik tussen verskillende habitats verwissel. Sy was in die bos, water, op landbougrond asook in digbevolkte gebiede, byvoorbeeld onder 'n baie gebruikte houtbrug, waargeneem.[16]

Jong Afrika-rotsluislange swerf dikwels ver rond op soek na kos en klim heel dikwels in bome om neste te bereik. Soos die slang groter word raak hy meer geneig om sy prooi in te wag. Meer dikwels is hy op die uitkyk vir prooi in die takke, op die rivieroewers of versteek naby die rand van 'n wildspaadjie. Soos alle luislange byt die Afrika-rotsluislang sy prooi en versmoor dit met sy dooddrukkende kronkels.[10]

Die prooi bestaan uit 'n verskeidenheid werweldiere, waaronder hoofsaaklik soogdiere en voëls, en tot 'n geringe mate ook reptiele en amfibieë. Die prooigrootte korreleer met die liggaamsgrootte van die luislange.[10] Navorsing in Suid-Nigerië het getoon dat daar in die natuurlike habitats van luislange met 'n totale liggaamslengte van onder 1,5 meter muissoorte, boomeekhorings, soneekhorings en vrugtevlermuise gevreet word. Individue onder 2,5 meter vang muskeljaatkatte, Mona-ape, reuserotte, rietrotte en duikers. Luislange van meer as 2,5 meter vang benewens dieselfde prooi ook dwergkrokodille en waterlikkewane.[17]

Verder vreet hierdie slangsoort ook verskeie paddaspesies,[10] diverse voëls soos die slanghalsvoël, duiker, rooibekkwelea, grootlangtoon, dwerggans, tarentaal, vinkspesies, rotspatrys, pelikaan[10] en kolgans en soogdiere soos die springhaas,[10] ystervark,[6] varkspesies[6] soos jong vlakvarke,[10] die husaaraap, Wes-Afrikaanse rooi stompaap en die Ethiopiese blouaap.[2] In gebiede met 'n hoë aantal soogdiere is groot Afrika-rotsluislange ook beduidende predatore van wildsbokke,[10] waar die slange van 4,5 meter lank nou en dan selfs prooidiere van meer as 30 kilogram kan baasraak.[6] Dit sluit in die Thompson-gaselle,[2] rooiboklammers, bosbokke, waterkoedoes en Bohorrietbokke asook die lammers van kobs en waterbokke.[6]

In die bewoonde gebiede van Suid-Nigerië vreet die Afrika-rotsluislange, met 'n totale lengte van minder as 2 meter, rotte as voorkeur, dié van 2 meter hoofsaaklik hoenders en die individue van meer as 3 meter selde ook honde en bokke. Luislange, wat in bewoonde gebiede jag, bereik deur hierdie prooi-inname gewoonlik 'n kleiner maksimumlengte as die slange in ongerepte areas.[17]

As gevolg van die groot verspreidingsgebied is die voortplantingstyd van die Afrika-rotsluislang uiteraard onderhewig aan geografiese variasie. Op die hoogtes van die ewenaar rondom die Victoriameer plant hierdie luislange weens geringe seisoenale klimaatskommelinge deur die jaar voort,[6] terwyl hulle in die lande in die noordweste, by name Kameroen en Gambië, tot die koel wintermaande beperk is.[2]

In Gambië is daar al groepe bestaande uit tot 6 slange oordag waargeneem wat styf aan mekaar geklou en oor mekaar gekruip het. Of slegs die een geslag (hetsy manlik of vroulik) betrokke was, kon nie vasgestel word nie. Volgens gevangenskapwaarneming baklei die Afrika-rotsluislangmannetjies in hierdie tyd deur hul koppe op te lig, hul nekke en lywe om mekaar te kronkel terwyl hulle mekaar grond toe probeer druk en met hul spore probeer krap.[2]

In gevangenskap duur die draagtyd tussen 30 tot 120 dae.[2] Voor die eiers gelê word, wat byvoorbeeld in Togo[18] met die reëntyd korreleer, soek die wyfie 'n skaduryke, veilige skuilplek in die nabyheid van water.[6] Hiervoor dien dikwels verlate gate van soogdiere, ou termiethope en diep rotsskeure. Indien sulke nesmaakplekke ontbreek, sal bosse, digte gras of blaarhope ook soms deug.[2]

Die broeiselgrootte is grootliks van die grootte en toestand van die wyfie afhanklik en bestaan gewoonlik uit 30 tot 50 wit eiers.[6] In Kameroen is selfs 'n legsel van 73 eiers[2] bekend en in die Londense Dieretuin het 'n baie groot wyfie in 1861 selfs omtrent 100 eiers[19] gelê. Die legsel van 'n gemiddelde 90 x 60 millimeter en ongeveer 150 gram eiers word deur die wyfie op 'n hopie gestapel. Sy kronkel dan om die broeisel om dit teen die nesrowers te beskerm en sal slegs sporadies die nes verlaat om water te gaan drink.[6][10] Deur die kronkels word vogtigheid en warmte gereguleer. Of die Afrika-rotsluislang deur spierbewing die inkubasietemperatuur kan beïnvloed, bly 'n twispunt. Die gegewens dui daarop dat die spesie, in teenstelling met die Suider-Afrikaanse luislang, daartoe in staat is.[20]

In Kenia[6] duur die broeityd ongeveer 60 dae, in Uganda[6] 90 dae en in Togo[18] word 70 tot 100 dae aangegee. Eiers wat teen 'n konstante temperatuur van 28 tot 32 ºC en 'n relatiewe humiditeit van 90% tot 100% kunsmatig geïnkubeer word, neem 50 tot 75 dae en dié teen laer temperature tot so 100 dae voor uitbroeiing.[2] Die pas uitgebroeide luislangetjies is gewoonlik 50 tot 65 sentimeter lank, weeg 75 tot 140 gram en is helderder en die patrone duideliker as die volgroeide luislange.[4] In 'n nes by die Tanganjika-meer in Tanzanië het die jong slangetjies ná die uitbroei nog enkele dae in die nes in 'n verlate ietermagôgat gebly, terwyl die wyfie 'n dag later die nes verlaat het. In pare of klein groepe bak die luislangetjies daagliks in die son; nooit verder as 4 meter van die gat af nie. Na die eerste vervelling ná sowat ses dae verlaat die eerste luislangetjies dan die nes.[21]

In gevangenskap bereik die slange geslagsrypheid binne drie tot vyf jaar en 'n totale lengte tussen twee en drie meter.[18] In Suidoos-Nigerië tree die geslagsrypheid in by 'n gemiddelde kop-romplengte van 1,70 meter.[7]

Inligting oor die gemiddelde en maksimumouderdom van vrylewende individue is onbekend. In gevangenskap word Afrika-rotsluislange in die reël 20 tot 25 jaar oud. In San Diego Dieretuin het 'n eksemplaar 27 jaar, 4 maande en 20 dae lank geleef.[6]

In sommige lande binne sy verspreidingsgebied word die Afrika-rotsluislang vir die leernywerheid gevang en verwerk. Party volkstamme nuttig hierdie spesie ook as voedselbron. Daarbenewens bestaan daar, ten minste in Nigerië, kommersiële handel met die vleis en internasionale handel met die afval vir die tradisionele medisyne.[17] Tot 'n mindere mate word ook lewendige Afrika-rotsluislange uitgevoer. In Togo is daar byvoorbeeld reptielplase begin. In praktyk word hoofsaaklik dragtige wyfies in die natuur gevang, tot net ná die broeityd aangehou en dan weer vrygelaat. Op hierdie wyse word die eiers kunsmatig uitgebroei en die uitgebroeide slangetjies verkoop.[18]

Die toenemende dorheid van die steeds uitbreidende Sahelstreek veroorsaak dat die verspreidingsgebied van die Afrika-rotsluislang al hoe meer inkrimp.[4] Die voortdurende mensgemaakte habitatsvernietiging en -verandering dra ook hiertoe by. Deur die konstante groeiende olienywerheid in Suid-Nigerië word daar byvoorbeeld in die Afrika-rotsluislang se habitat, die wortelboomwoude, ontgin. Die ontploffings, bou van kanale, strate en pypleidings verklein en vernietig hierdie habitat voortdurend. Alhoewel hierdie luislang baie aanpasbaar is en baie gebiede wat deur die mens verander is kan bewoon, is sy bevolkingstal in sommige lande aan die agteruitgaan.[7]

CITES beskou hierdie luislang as bedreig, is gelys in Bylae II en is onderhewig aan handelsbeperkings.[22]

Die Afrika-rotsluislang se wetenskaplike naam, Python sebae, vereer die Duits-Nederlandse natuurversamelaar, Albert Seba.

Die verwantskap tussen die groot Afrikaanse luislange, Python sebae (Gmelin 1789), Python natalensis (Smith 1840) en Python saxuloides (Miller&Smith 1979)[23] was lank onduidelik. Daar was 'n gebrek aan eksemplare van elke spesie, veral uit die plekke waar hul simpatries[24] of parapatries[25] voorkom. Daarom is hierdie luislange in die 20ste eeu grotendeels slegs as 'n eensoortige spesie erken, naamlik Python sebae.[20] Aan die hand van 'n groot dataversameling kon Broadley (1984) luislange in 'n noordelike en 'n suidelike verspreidingsgebied afkamp, hoofsaaklik op grond van die fragmenteringssterkte van die skilde van die bokant van die kop en die patroon van die sykant van die kop. Vanweë moontlike kruisings in die oorvleuelende verspreidingsgebiede klassifiseer hy al twee groepe as subspesies en benoem die noordelike vorm Python sebae en die suidelike vorm Python sebae natalensis. Python saxuloides blyk toe 'n afwykende Keniaanse bevolking van Python sebae natalensis te wees en word met laasgenoemde gelykgestel.[5] In 1999 ken Broadley beide subspesies 'n spesiestatus toe, omdat nuwe akkurater gegewens uit die gebiede met uitgebreide simpatrie in Burundi, Kenia en Tanzanië op geen kruising dui nie.[14] In 2002 word egter berig van hibriedes naby die Tanzaniese stad Morogoro.[20] Die klassifikasie van die twee afsonderlike spesies is egter nog op grond van die huidige gegewens van krag. Daar moet verdere bewyse van hibridisering gevind of 'n genetiese ontleding verkeerd bewys word om die spesiestatus ongedaan te maak.[20]

Onder die egte luislange (Pythons) is Python sebae en die Suider-Afrikaanse luislang die nouste verwant aan die Suid- en Suidoos-Asiese Indiese en Birmaanse luislang. Dit blyk uit 'n onlangse molekulêrgenetiese ondersoek van Python sebae en die Indiese en Birmaanse luislang.[26]

Wildlewende Afrika-rotsluislange vermy konfrontasie met mense. Kom hulle wel 'n mens teë, soek hulle gewoonlik skuilplek of vlug die water in.[7] By groter verontrusting, veral wanneer hul in 'n hoek gedryf word, gaan party slange egter vinnig tot die verdediging oor en byt met hul lang voortande heftig en herhaaldelik, wat tot diep en septiese wonde lei.[6] Sommige individue laat mens egter ook baie naby aan hul naderkom en verstar op die plek, of kruip stadig weg.[2] Daar bestaan enkele gerugte dat die Afrika-rotsluislang in die natuur mense sou aangeval en gedood het. Daar is egter geen betroubare bewyse hiervoor nie.[9]

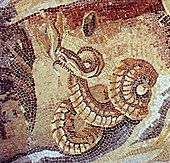

Reeds in die Oudheid word aan die Afrika-rotsluislang aandag geskenk. So het die ou Grieke reeds 'n paar eeue v.C. geweet van die reuseslange in Nubië. Die Grieke beskou hierdie slange as tipies van daardie plaaslike diereryk en glo dat die luislange soms selfs olifante sou vreet. Ptolemeus II, wat van 282 tot 246 v.C. die tweede Ptolemeuse koning van Egipte was, belas 'n groep van 100 man, bestaande uit jagters, perderuiters, slingeraars, trompetblasers en boogskutters om een van die grootstes van hierdie slange te vang en lewendig na sy wyd bekende dieretuin te bring. In Suid-Nubië, waar die Afrika-rotsluislang toe nog verspreid was, het die mans toe na verskeie pogings daarin geslaag om 'n uiters weerbare individu met 'n totale lengte van glo oor die 13 meter te vang en na die koning te bring. Hierdie "ondier" is toe in die dieretuin gevoer en getem en was Ptolemeus se buitengewoonste en bekendste dier. Die Afrika-rotsluislang was ook herhaaldelik die onderwerp in mosaïekwerke. In die Nylmosaïek van Palestrina, wat omstreeks 200 v.C. ingeleg is, word 'n groot luislang wat om 'n rots kronkel uitgebeeld. In dieselfde mosaïekwerk is daar 'n tweede luislang te sien wat langs die Nyloewer 'n voël regop insluk.[27] Op 'n ander mosaïekstuk van die voormalige Romeinse Kartago, wat tussen die tweede en vierde eeu n.C. geskep is, is 'n luislang te sien wat met 'n olifant baklei.[2]

In die ou Romeinse Ryk is gedurende die sirkusspele dikwels slange ten toon gestel. Die halfgetemde Afrika-rotsluislang het daarby ook as aantreklikheid gedien.[28]

Voor kolonialisering het daar reeds in sommige Wes-Afrikaanse kulture 'n slangkultus bestaan. Die Afrika-rotsluislang en die koningsluislang word as heilig beskou, in slangtempels aangehou en aanbid. Tydens seremonies bring hul aan die Afrika-rotsluislang talle geskenke en paai hom met die offer van 'n hoender of lam.[28] Hierdie luislang het byvoorbeeld in Nigerië so 'n hoë waarde, dat selfs een van die eerste verdrae tussen die Engelse koloniste en stamhoofde rondom die beskerming van hierdie slangsoort handel.[7] Tot op datum word hierdie slangspesie in baie dele van sy verspreidingsgebied verafgod. In Suid-Soedan glo byvoorbeeld die Dinka, Sjilloek en Bari dat sekere individuele slange afgestorwe siele beliggaam. Hierdie luislange geniet daar die allergrootste respek, word offergawes aan gebring en daar word tot hul gebid om ellende, siekte, droogte en hongersnood te besweer.[29]

In sommige plaaslike gemeenskappe is die geloof wydverspreid dat ná die doding van 'n Afrika-rotsluislang geen reën meer sal val nie.[6] Sommige groepe, insluitend ook diegene wat slegs enkele individue verafgod, dood Afrika-rotsluislange om voedsel en vir tradisionele medisyne.[29] In byvoorbeeld die Demokratiese Republiek van die Kongo word hulle met spiese gejag of by die ingang van hul wegkruipplekke met strikke gevang. Die vleis is smaaklik, proe soos Atlantiese kabeljou, en die luislangvet het na bewering merkwaardige geneeskragte om talryke siektes te genees.[6]

Op die Adamawa-plato in Kameroen, naby Ngaoundéré, is daar die sonderlinge (maar ook sterwende) gebruik by die Gbaya om die gbagok – groot slang – uit sy gate te jag. Daar word geglo dat die luislang, die koning van die slange, aan die begin van die wêreld as afstammeling van 'n draak uitgebroei het. Die luislange word gejag vir hul vleis en vel. In die droë seisoen, wat strek vanaf November tot Maart, seil die luislange na uitgediende erdvarkgate om in 'n rustende toestand te verkeer of om hul eiers te lê.

Die jagtog word voorafgegaan deur die ruigte bo die gate af te brand. Net voor die jagtog word 'n hoender geslag en die bloed op die jagter se mes en spies gesprinkel om voorspoed van die voorouers te vra. Die luislangspoor in die as word gevolg, waarna die jagter met flitse (meestal brandende strooi as fakkel) al swetend langs die nou erdvarkgangetjies "inseil". Indien die tonnel te nou of steil is, moet die jagters 'n reeks gate in die klipharde grond grawe, soms tot 4,572 m (15 vt.) diep, om die kamer te vind waar die Afrika-rotsluislang opgekrul lê.

In die regterhand word die vlam as afskrikmiddel gebruik. Die linkerhand van die jagter word met bokvel beskerm om later die luislang se oë te bedek wanneer net agter die kop vasgegryp word. Die meeste luislange is dan, vreemd genoeg, redelik onaggressief. Sodra die luislang stewig met al twee hande vasgevat is, kruip die jagter stadig agteruit. Omrede die luislang geleidelik (en blindelings) teruggetrek word, bly die slang kalm en bied geen weerstand nie. Sodra die slang uit sy wegkruipplek gesleep is, poog hy met moeite om terug na die gat te keer of kronkel om die vyand. Om hierdie aksie te verhoed, pen die jagter die slang se kop met 'n gevurkte stok teen die grond vas, terwyl sy handlanger aan die slang se stert trek. Die luislang se keel word uiteindelik op so 'n wyse afgesny dat die slangvel nie beskadig word nie. Hierdie vel word naby 'n kampvuur gespan om droog te word. Die vleis en vel was in 1997 omtrent VS$60,00 werd.

Sou die jagter die vleis na 'n ouer persoon bring, sal laasgenoemde die jagter se hande vashou en daarin spoeg as seëngebaar.[30][31]

Die Afrika-rotsluislang (Python sebae) is 'n slangsoort van die familie luislange (Pythonidae) en word by die genus egte luislange (Python) ingedeel. Hy verskil wat velpatroon en skubbe betref van die Suider-Afrikaanse luislang. Met 'n bevestigde lengte van meer as vyf meter is die Afrika-rotsluislang een van die grootste slange ter wêreld. Sy verspreidingsgebied strek in Afrika besuide die Sahara van die weskus tot die ooskus en suidwaarts tot in die noorde van Angola. Hier woon hy in 'n verskeidenheid tropiese en subtropiese landskappe nooit te ver van water nie. Hy is baie aanpasbaar en bewoon as kultuurvolger ook landbougrond en nedersettings.

Die dieet bestaan uit 'n verskeidenheid gewerwelde diere. In die gebiede met 'n hoë aantal soogdiere, vreet groot individue heel dikwels wildsbokkies wat selde meer as 30 kilogram weeg.

Krajta písmenková (Python sebae) je jedním z největších hadů světa dorůstajících délky až 7 m a hmotnosti kolem 100 kg. Většinou však dorůstají pouze 3 - 4,5 metru, samci necelé 4 metry.

Tento mohutný had obývá převážně západní Afriku od tropické oblasti (Zaire, Uganda, Súdán a Etiopie), až po jižní okraj Sahary. V dospělosti vyhledává spíše sušší biotopy, otevřené roviny savanového typu a řídké křoviny. Krajta písmenková je aktivní spíše v noci, kdy nejčastěji loví.

Zbarvení krajty písmenkové je hnědé až šedohnědé, s červenohnědými až černými skvrnami na zádech. Skvrny jsou od středu světlé, a směrem k okrajům tmavší, až černé. Podobné, pravidelné skvrny tvaru půlměsíce se táhnou i po bocích hada. Klínovitá hlava s dvěma světlými pruhy u oka, a výraznými receptory na horní i dolní čelisti, je jen nevýrazně oddělena od těla.

Její kořistí se stávají převážně potkani, zajíci a ptáci, opice, některé druhy antilop a divoká prasata. Na kořist většinou číhá z vyvýšeného místa, odkud se jí bleskovým výpadem zmocní. Doma chovaní hadi přijímají potkany, králíky a morčata, občas můžeme zpestřit jídelníček slepicí. Velcí jedinci s chutí vezmou i zvíře velikosti 10 kg selete.

Kořist zabíjí uškrcením, jako většina krajt.

Tak jako všichni velcí hadi, potřebuje i krajta písmenková velké, dobře zajištěné terárium, jehož délka by měla tvořit alespoň polovinu délky chovaného hada. Jako substrát můžeme použít např. směs písku a štěrku, nebo zvolit tzv. sterilní chov, kdy podlahu terária tvoří dřevěný rošt, nebo jiný hladký a omyvatelný materiál. Nezbytná je bytelná a velká vodní nádrž, kterou krajta písmenková často navštěvuje. Teplotu udržujeme na 25 - 32 °C přes den, v noci můžeme nechat klesnout teplotu až k 18 °C. Jedinci z přírody - zvláště z jihu Afriky by měli 2 - 4 měsíce zimovat.

K páření dochází zhruba v listopadu až březnu. Dospělé hady můžeme k páření stimulovat snížením teploty asi na 22 °C a zkrácením dne na 8 - 10 hodin při častém, ale jemném rosení. Samice naklade asi 20 - 80 vajec (podle velikosti samice), které po vzoru mnohých krajt zahřívají vlastním tělem. Mláďata se líhnou při inkubační teplotě 30 °C za 70 - 80 dní. Jsou kolem 70 cm dlouhá a ihned po prvním svlečení s chutí loví dospělé myši. Zdržují se převážně v okolí vodních zdrojů. Bývají kousavá a s přibývajícím věkem se to většinou nelepší. Pohlavní dospělosti dosahují už ve 2 - 4 letech, pářit se začínají přibližně ve velikosti těsně přes 2 metry.

Pro chov krajty písmenkové je nutné povolení. Vzhledem ke své agresivitě a kousavosti ji nelze doporučit pro chov v bytech a její chov by měl být omezen na zkušené teraristy a kompetentní pracoviště. Všeobecně se má zato, že tento had je nejagresivnější ze všech krajt a ani mláďata odchovaná v zajetí na tom nebývají až na výjimky o mnoho lépe.

Krajta písmenková (Python sebae) je jedním z největších hadů světa dorůstajících délky až 7 m a hmotnosti kolem 100 kg. Většinou však dorůstají pouze 3 - 4,5 metru, samci necelé 4 metry.

Klippepytonen (Python sebae) stammer fra Afrika, og anses for at være en af de største slangearter i verden. Klippepytonen er en udbredt art, som er fast etableret i Florida, da slangerne er blevet holdt som kæledyr siden firserne. Efter et par år i fangeskab bliver slangerne for store som kæledyr, derfor bliver de skyllet ud i kloakken når de opnår for stor en størrelse. Klimaet i Florida er nogenlunde lig med det Østafrikanske klima, så slangen har nemt kunne overleve i sumpområderne uden for storbyen. Det har skabt store problemer, ikke mindst for andre dyrearter, men også for menneskenes sikkerhed. Heldigvis ramte en historisk sjælden snestorm Florida, hvor en stor mænge slanger blev udryddet.

Der Nördliche Felsenpython (Python sebae), auch kurz Felsenpython, zählt zur Familie der Pythons (Pythonidae) und wird dort in die Gattung der Eigentlichen Pythons (Python) gestellt. Er unterscheidet sich durch Beschuppungs- und Musterungsmerkmale vom Südlichen Felsenpython. Mit gesicherten Längen über fünf Meter gehört der Nördliche Felsenpython zu den größten Schlangen der Welt. Sein Verbreitungsgebiet erstreckt sich in Afrika südlich der Sahara von der Westküste bis zur Ostküste und südlich bis in den Norden von Angola. Hier bewohnt er eine Vielzahl tropischer und subtropischer Landschaften in nicht zu großer Entfernung von Gewässern. Er ist sehr anpassungsfähig und besiedelt als Kulturfolger auch landwirtschaftliche Nutzflächen und Siedlungen.

Die Nahrung besteht aus einer Vielzahl unterschiedlicher Wirbeltiere. In Gebieten mit hohen Säugerbeständen erbeuten große Individuen relativ häufig kleine Antilopen, die selten sogar über 30 Kilogramm schwer sein können. Der Python tötet seine Beute durch Erwürgen.

Juvenile Tiere sind recht schlank gebaut, werden jedoch mit zunehmendem Alter von immer kräftigerer Statur. Bei großen adulten Nördlichen Felsenpythons plattet sich der zylindrische Körper geringfügig ab. Der breite, dreieckige, leicht abgeflachte, große Kopf ist deutlich vom Hals abgesetzt. Die Schnauze ist auf der Oberseite gegen die Spitze hin abgerundet. Ihr sitzen die Nasenlöcher schräg zwischen Kopfoberseite und Kopfseite auf. Der spitz zulaufende Greifschwanz macht bei Weibchen zwischen 9 und 14 % und bei Männchen zwischen 11 und 16 % der Gesamtlänge aus.

Das Gebiss besteht aus dünnen, länglichen Zähnen, die durchgehend spitz und zum Rachen hin gebogen sind und von der Maulspitze zum Rachen hin zunehmend kleiner werden. Am vorderen Teil der oberen Mundhöhle befindet sich das Zwischenkieferbein mit zwei kleinen Zähnen. Die Oberkieferknochen tragen jeweils 13 bis 16 Zähne. Gegen die Mitte der oberen Mundhöhle liegen parallel zu den Oberkieferknochen vorne das Gaumenbein und weiter hinten das Flügelbein. Das erstgenannte hat 6 bis 7 und das andere 8 bis 9 Zähne. Die Unterkiefer tragen jeweils 13 bis 17 Zähne.[1]

Die Kopfoberseite ist charakteristischerweise von großen Schuppen bedeckt: Die Nasalia (Nasenschilde) sind voneinander durch ein Paar viereckiger Internasalia (Zwischennasenschilde) getrennt. Das anschließende markant ausgebildete Paar Präfrontalia (Vorstirnschilde) wird durch eine Reihe weniger, unregelmäßiger Schilde vom dahinter folgenden großen Paar Frontalia (Stirnschilde) separiert. Letzteres Paar kann gelegentlich partiell oder komplett fusioniert sein. Das Supraoculare (Überaugenschild) ist groß und vereinzelt zweigeteilt. Seitlich befinden sich zwischen Auge und Nasenloch mindestens drei bis vier Lorealia (Zügelschilde) von unterschiedlicher Größe sowie zwei Präocularia (Voraugenschilde), von denen das untere klein und unregelmäßig geformt ist. Postocularia (Hinteraugenschilde) existieren beidseits zwei bis vier. Das Rostrale (Schnauzenschild) hat, wie bei den meisten anderen Pythons auch, zwei tiefe Labialgruben. Von den 13 bis 16 Supralabialia (Oberlippenschilden) sind das zweite und dritte mit feinen Labialgruben versehen. Die 19 bis 25 Infralabialia (Unterlippenschilde) werden zur Schnauzenspitze hin zunehmend kleiner. Die zwei vordersten und die drei bis vier hintersten tragen feine Labialgruben.[2] Die Anzahl der Ventralia (Bauchschilde) variiert je nach Herkunft der Individuen zwischen 265 und 283, die Anzahl der dorsalen Schuppenreihen in der Körpermitte zwischen 76 und 98. Von der Kloake bis zur Schwanzspitze finden sich 62 bis 76 paarige Subcaudalia (Schwanzunterseitenschilde).[3] Das Anale (Analschild) kann ungeteilt oder geteilt sein.[2]

Die Grundfarbe reicht von gelb, beige, hellbraun bis grau.[2] Auf dem Rücken verlaufen große, unregelmäßige, von Individuum zu Individuum im Aussehen variierende braune Sattelflecken. Sie besitzen schwarze Ränder und werden ringsum durch eine breite helle Aussparung von der Grundfarbe abgegrenzt. Auf der Flankenseite haben die Sattelflecken teilweise Längsverbindungen zueinander und schließen so zahlreiche große, ausgedehnte, helle Areale auf dem Rücken ein.[3] Auf den Flanken verlaufen alternierend zur Rückenmusterung braune, rechteckige Flecken mit aufgehelltem Zentrum. In der hinteren Körperhälfte werden die Flankenflecken zunehmend dünner und verschmelzen häufig mit den Sattelflecken.[2] Bei den meisten Tieren bleibt zwischen der dunklen Musterung der Schwanzoberseite zentral eine lange, hellbraune streifenförmige Aussparung frei. Die Bauchseite ist gräulich bis gelblich und mit dunklen Punkten versehen.[3]

Der Kopf ist kontrastreich gezeichnet. Auf den Kopfseiten verläuft bei den meisten Tieren ein heller Streifen von unterhalb der Nase schräg nach hinten auf den zweiten Oberlippenschild. Dahinter folgt zwischen Nase und Auge ein breiter dunkler Fleck. Anschließend ziehen zwei weiße Bänder unterhalb des Auges bis zur Oberlippe und schließen in ihrer Mitte ein dunkles Dreieck ein. Hinter dem Auge bis zum Maulwinkel verläuft ein dunkelbrauner Streifen, der typischerweise breiter als der Augendurchmesser ist. Die Kopfoberseite trägt ein pfeilspitzenförmiges, braunes Muster, das von der Nase über die Augen bis zum Nacken zieht und in seiner Mitte einen hellen Punkt aufweist. Die Unterlippe trägt meist dunkle Flecken. Der Rest der Kopfunterseite ist weiß, erst hinter der Kehle grenzen kräftige dunkle Flecken der Halsunterseite an. In der bräunlichen Iris ist die schwarze Pupille gut erkennbar.[3]

Nördliche Felsenpythons erreichen durchschnittlich eine Gesamtlänge zwischen 2,7 und 4,6 Meter.[4] Dies bestätigt eine Studie in Südost-Nigeria, wo die durchschnittliche Kopf-Rumpf-Länge von 39 adulten Männchen im Mittel 2,47 Meter betrug. Die 51 untersuchten adulten Weibchen waren mit einer durchschnittlichen Kopf-Rumpf-Länge von 4,15 Meter signifikant größer. Das größte unter ihnen war zirka 5 Meter lang.[5] Gesicherte Angaben zur maximalen Körperlänge dieser Art gibt es nicht. Gemäß Villiers (1950) soll 1932 in Bingerville an der Elfenbeinküste ein Individuum mit 9,8 Meter Gesamtlänge erlegt worden sein.[6] Nach Branch (1984)[7] und Spawls et al. (2002)[8] handelt es sich dabei aber um eine unseriöse, unglaubwürdige Überlieferung. Daneben existieren weitere unbelegte Angaben von über 7 Meter langen Tieren. Wiederholt wurden auch massiv überdehnte Häute für Längenrekorde gehalten. So hat Loveridge 1927[9] in Ostafrika eine 9,1 Meter lange Haut vermessen. Wenngleich diese Haut vermutlich um mehr als ein Viertel gedehnt war, könnte sie doch ursprünglich einem Nördlichen Felsenpython von über 6,5 Meter Gesamtlänge gehört haben.[10] Der längste bisher offenbar seriös vermessene Nördliche Felsenpython stammt aus Uganda und hatte laut Pitman (1974) eine Gesamtlänge von 5,5 Meter (18 ft).[4]

Das Verbreitungsgebiet des Nördlichen Felsenpythons reicht südlich der Sahara von der westafrikanischen Küste nach Osten über 6600 Kilometer fast bis zum sogenannten Horn der Ostküste. In Westafrika wurde die Art in Südmauretanien,[11] Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, der Elfenbeinküste, Südmali, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Südniger und Nigeria nachgewiesen. In Zentralafrika ist sie im Südtschad, in Kamerun, der Zentralafrikanischen Republik, Äquatorialguinea, Gabun, der Republik Kongo, der Demokratischen Republik Kongo und Nordangola zuhause. Im Osten findet man diesen Python im Südsudan, in Äthiopien, Somalia, Kenia, Uganda, Ruanda, Burundi und Tansania.[3]

Es wird vermutet, dass sich der Südliche Felsenpython einst nordwärts entlang des westlichen und östlichen Tales des Großen Afrikanischen Grabenbruchs in vom Nördlichen Felsenpython dominierte Areale ausgebreitet hat.[12] In Kenia überschneiden sich 40 Kilometer nordwestlich von Mwingi heute noch immer die Gebiete der beiden Arten. Auch in Burundi und im Osten der Kivu-Provinz der Demokratischen Republik Kongo sind Reliktpopulationen vorhanden. In Tansania besteht eine extensive Überlappung der Verbreitungsgebiete der beiden Arten auf etwa 900 Kilometer.[12] In Angola weisen bisherige Untersuchungen auf eine vollständige räumliche Trennung der beiden Arten hin.[3]

Der Nördliche Felsenpython bewohnt eine Vielzahl unterschiedlicher Habitate der Tropen und Subtropen, darunter Mangrovenwald, Buschland, permanent überfluteten Sumpfwald, sekundären Sumpfwald, dichten und aufgelockerten Trockenwald,[1] Grasland und Sandebenen. Als Kulturfolger bewohnt er oft Maniok-, Ananas-, Süßkartoffel- und Ölpalmplantagen sowie Felder. Ziemlich häufig lässt er sich auch relativ unauffällig an Stadtrandsiedlungen nieder. Voraussetzung für eine Besiedlung aller Lebensräume ist stets Gewässernähe. So bewohnt er meist Areale entlang von permanenten Weihern, Seen, Bächen, Flüssen und teilweise auch Brackwasser.[5] In Süd-Mauretanien lebt er jedoch auch in Feuchtgebieten, wo Gewässer jährlich komplett austrocknen können und dann nur noch fleckenweise Ufervegetation als Rückzugsgebiete zur Verfügung steht.[11] Sehr feuchte Gebiete werden von dieser Schlange gemieden. So ist diese Spezies im Regenwald kaum zu finden.[13] In Ruanda erreicht die Art Höhenlagen von mehr als 1350 Meter über Meer und in Uganda ist sie sogar schon auf 2250 Meter über Meer nachgewiesen worden. In Kenia und Nord-Tansania, wo sich die Verbreitung des Nördlichen- und Südlichen Felsenpythons überschneiden, ist die nördliche Art primär in niedrigeren Höhenlagen präsent.[3]

Der Nördliche Felsenpython ist vorwiegend bodenbewohnend und kann sich hier selbst als großes erwachsenes Tier noch ziemlich zügig[4] fortbewegen. Als guter Kletterer hält er sich regelmäßig auch auf Bäumen auf, um zu jagen oder Raubfeinden auszuweichen. Insbesondere junge und subadulte Nördliche Felsenpythons von unter 1,8 Meter Gesamtlänge sind oft in Bäumen und Sträuchern zu finden. Erwachsene Tiere gelten als weniger häufig kletternd. Adulte Pythons mit einer Gesamtlänge von über 2,5 Meter sind gute Schwimmer und verbringen oft längere Perioden im Wasser. Über das Vorkommen von Jungtieren in Gewässern liegen bisher keine Erkenntnisse vor.[5] Am Victoriasee legen diese Pythons gelegentlich beachtliche Strecken frei schwimmend zwischen Inseln und dem Festland zurück.[4] Des Weiteren sind sie vermutlich fähig, selbst im Meer mehrere Kilometer schwimmend zurücklegen. Hierdurch wird beispielsweise das Vorkommen auf der küstennahen Chula-Insel der Bajuni-Inseln in Süd-Somalia erklärt.[1] In Uganda wird das Wasser insbesondere während der heißen Tage der Trockenzeit genutzt, um den Körper im seichten Wasser, nur mit den Nasenlöchern über die Wasseroberfläche ragend, zu kühlen.[4] Flüsse und Bäche werden von dieser Schlange auch benutzt, um auf der Suche nach Beute in besiedeltes Gebiet vorzudringen. Das Gewässer gilt dabei als Ausgangspunkt für die Futtersuche und beim Rückzug als schützendes Versteck.[5]

In Gebieten wie Südost-Nigeria, wo das Klima jahreszeitlichen Schwankungen unterliegt, zeigt die Art ein über das Jahr hinweg variables Aktivitätsmuster. Aktivitätsmaxima werden während der Trockenzeit im Januar und während der letzten Phase der Regenzeit von August bis September beobachtet.[5] In den äquatorial gelegenen Ländern Kenia und Uganda werden diese Pythons als überwiegend dämmerungs- und nachtaktiv beschrieben, wobei sie gelegentlich auch tagsüber beim Sonnen oder Futtersuchen beobachtet werden.[4][8] Eine genauere Untersuchung im etwas nördlicheren Südost-Nigeria hat ergeben, dass Nördliche Felsenpythons in menschenfernen Arealen hauptsächlich tagaktiv sind. Die meisten Tiere werden hier am Nachmittag zwischen 15:00 bis 17:30 Uhr beobachtet. In stark bewaldeten Gebieten, besonders entlang von Bächen und Flüssen, ist die Art vom frühen Morgen bis zum Mittag am bewegungsfreudigsten. Hingegen sind Nördliche Felsenpythons in der Nähe von menschlichen Siedlungen und Stadtgebieten vorwiegend dämmerungs- und nachtaktiv mit Aktivitätsmaxima während der Abenddämmerung.[5]

Während der inaktiven Phasen sucht sich diese Schlange Versteckplätze beispielsweise im dichten Gebüsch, in Ufervegetation, im Wasser, auf Bäumen, in Felsspalten, in hohlen Baumstämmen[13] und verlassenen Höhlen von Warzenschweinen, Erdferkeln[1] oder Stachelschweinen. Dabei ringelt sich der Python meist zu einem Knäuel zusammen, wobei sein Kopf zuoberst ruht.[8]

Angaben zu Aktionsräumen und Habitatwechseln wurden bisher nur bei einem Individuum in Südwest-Kamerun erhoben. Es handelte sich um ein über ein Jahr hinweg mittels Peilsender beobachtetes Weibchen mit einer Kopf-Rumpf-Länge von 2,4 Meter und einer Masse von 3,7 Kilogramm. Dieses Tier bewegte sich primär in einem Kernareal von 2,4 Hektar, entfernte sich meist nicht weiter als 10 Meter von Gewässern und wechselte häufig und wiederholt zwischen mehreren unterschiedlichen Lebensräumen. Es wurde sowohl im Wald, am und im Wasser, auf Farmland als auch in stark besiedeltem Gebiet, beispielsweise unter einer aktiv genutzten Holzbrücke, gesichtet.[13]

Juvenile Nördliche Felsenpythons wandern auf der Suche nach Beute oft weit umher und klettern häufig auf Bäume, um Nester zu erreichen. Mit zunehmender Größe tendiert die Art immer mehr zur Lauerjagd, wobei die Beute oft aus Verstecken am Rande von Wildtierpfaden oder gut getarnt am Ufer von Gewässern abgepasst wird. Wie alle Riesenschlangen verbeißt sich der Nördliche Felsenpython dann in die Beute und erstickt sie durch Umschlingen.[8]

Das Beutespektrum besteht aus einer Vielzahl unterschiedlicher Wirbeltiere, darunter hauptsächlich Säugetiere und Vögel, zu einem geringen Teil auch Reptilien und Amphibien. Die Beutegröße korreliert dabei mit der Körpergröße des Pythons.[8] Eine Studie in Süd-Nigeria hat gezeigt, dass hier in natürlichen Habitaten von Pythons mit einer Gesamtlänge unter 1,5 Meter Mäuseartige, Rotschenkelhörnchen, Sonnenhörnchen und Flughunde gefressen werden. In Individuen unter 2,5 Meter wurden Ginsterkatzen, Monameerkatzen, Riesenhamsterratten, Rohrratten und Ducker nachgewiesen. Tiere von über 2,5 Meter Gesamtlänge erbeuteten neben den Beutetieren der unter 2,5 Meter langen Individuen auch Stumpfkrokodile und Nilwarane.[14]

Des Weiteren frisst die Art auch mehrere Froscharten,[8] diverse Vögel wie Afrikanische Schlangenhalsvögel, Kormorane, Blutschnabelweber, Blaustirn-Blatthühnchen, Afrikanische Zwergenten, Helmperlhühner, Webervögel, Felsenrebhühner, Pelikane[8] und Nilgänse und Säugetiere wie Springhasen,[8] Stachelschweine,[4] Vertreter Echter Schweine,[4] darunter junge Warzenschweine,[8] Husarenaffen, Westafrikanische Stummelaffen und Äthiopische Grünmeerkatzen.[1] In Gebieten mit hohen Säugerbeständen sind große Nördliche Felsenpythons auch signifikante Prädatoren von Antilopen,[8] die bei Individuen ab Gesamtlängen von 4,5 Meter mitunter sogar über 30 Kilogramm schwer sein können.[4] Dazu zählen Thomson-Gazellen,[1] Jungtiere von Impalas, Buschböcken, Sitatungas und Riedböcken sowie Kitze von Kobs und Wasserböcken.[4]

In bewohnten Gebieten Süd-Nigerias ernähren sich Nördliche Felsenpythons mit einer Gesamtlänge von unter 2 Meter bevorzugt von Ratten, solche ab 2 Meter primär von Hühnern und Individuen mit einer Gesamtlänge von über 3 Meter selten auch von Hunden und Ziegen. Pythons, die in bewohnten Gebieten jagen, erreichen durch dieses Beuteangebot gewöhnlich eine kleinere maximale Gesamtlänge als Tiere in unberührten Arealen.[14]

Aufgrund des großen Verbreitungsgebietes unterliegt die Fortpflanzungszeit des Nördlichen Felsenpythons offenbar geografischer Variation. Auf Höhe des Äquators rund um den Victoriasee pflanzen sich diese Pythons auf Grund der geringen saisonalen Klimaschwankungen über das ganze Jahr hinweg fort,[4] während aus den nordwestlicher gelegenen Ländern Kamerun und Gambia von einer auf die kühlen Wintermonate beschränkten Paarungszeit berichtet wird.[1]

In Gambia konnten dabei schon Gruppen von bis zu 6 Tieren beobachtet werden, die sich untertags dicht aneinander schmiegten und übereinander hinwegkrochen. Um was für eine Geschlechterverteilung es sich dabei gehandelt hat, konnte nicht eruiert werden. Gefangenschaftsbeobachtungen zufolge liefern sich Nördliche Felsenpythonmännchen in dieser Zeit Kommentkämpfe, wobei die Kontrahenten ihre Köpfe anheben, gegenseitig ihre Hälse umschlingen und versuchen, den Gegner zu Boden zu drücken. Dies kann auch in ausgedehntes Körperumwickeln mit Zudrücken sowie Kratzen mittels Afterspornen übergehen.[1]

In Gefangenschaft dauert die Tragzeit zwischen 30 und 120 Tage.[1] Für die Eiablage, die beispielsweise in Togo[15] mit der Regenzeit korreliert, sucht sich das Weibchen ein schattiges, geschütztes Versteck in der Nähe eines Gewässers.[4] Oft dienen dazu verlassene Höhlen von Säugetieren, alte Termitenhügel und tiefe Felsspalten. Wenn solche Nistorte fehlen, werden gelegentlich auch Gebüsche, dichtes Gras und Laubhaufen akzeptiert.[1]

Die Gelegegröße ist stark von der Größe und Verfassung des Weibchens abhängig und umfasst gewöhnlich zwischen 30 und 50 weißliche Eier.[4] Aus Kamerun ist sogar ein Gelege mit 73 Eiern[1] bekannt und im Londoner Zoo soll ein sehr großes Weibchen 1861 sogar an die 100 Eier[16] gelegt haben. Die Gelege aus durchschnittlich 90 × 60 Millimeter messenden, etwa 150 Gramm schweren Eiern werden vom Weibchen zu einem Haufen geformt, umringelt, vor Nesträubern beschützt und nur sporadisch verlassen, um zu trinken.[4][8] Durch die Schlingenanordnung werden Feuchtigkeit und Wärme reguliert. Ob Nördliche Felsenpythons zum Muskelzittern befähigt sind und dadurch die Inkubationstemperatur beeinflussen können, wird kontrovers diskutiert. Einiges deutet darauf hin, dass die Art im Gegensatz zum Südlichen Felsenpython dazu im Stande ist.[17]

In Kenia[4] dauert die Brutzeit zirka 60 Tage, in Uganda[4] 90 Tage und in Togo[15] wird von 70 bis 100 Tagen berichtet. Eier, die künstlich bei einer konstanten Temperatur von 28 bis 32 °C und einer relativen Luftfeuchtigkeit von 90 bis 100 % inkubiert wurden, benötigen 50 bis 75 Tage und solche unter niedrigeren Temperaturen bis zu 100 Tage bis zum Schlupf.[1] Die Schlüpflinge messen meist 50 bis 65 Zentimeter, wiegen 75 bis 140 Gramm und sind heller und deutlicher gemustert als adulte Tiere.[2] Bei einem Gelege am Tanganjikasee in Tansania blieben Jungtiere nach ihrem Schlupf noch mehrere Tage am Nistplatz in einem verlassenen Schuppentierbau zurück, während die Mutter schon einen Tag später das Nest verließ. In Paaren bis kleinen Gruppen wärmten sich die Jungtiere täglich, nicht weiter als vier Meter von der Höhle entfernt, ausgiebig an der Sonne. Nach der ersten Häutung nach zirka sechs Tagen verließen dann die ersten Jungtiere das Nest.[18]

In Gefangenschaft wird die Geschlechtsreife mit drei bis fünf Jahren und einer Gesamtlänge zwischen zwei und drei Meter erreicht.[15] In Südost-Nigeria trat die Geschlechtsreife bei einer durchschnittlichen Kopf-Rumpf-Länge von 1,70 Metern ein.[5]

Angaben zum Durchschnitts- und Maximalalter freilebender Individuen sind unbekannt. In Gefangenschaft werden Nördliche Felsenpythons regelmäßig 20 bis 25 Jahre alt. Im San Diego Zoo hat ein Exemplar 27 Jahre, 4 Monate und 20 Tage gelebt.[4]

In einigen Ländern seines Verbreitungsgebietes wird der Nördliche Felsenpython für die Ledergewinnung gefangen und verarbeitet. Gewisse Volksstämme nutzen die Art auch als Nahrungsquelle. Daneben existiert, zumindest in Nigeria, ein kommerzieller Handel mit dem Fleisch und ein internationaler Handel mit den Innereien für die traditionelle Medizin.[14] In kleinen Mengen werden auch lebendige Nördliche Felsenpythons exportiert. In Togo haben sich beispielsweise Reptilienfarmen etabliert. Hier werden primär trächtige Weibchen aus der Natur gefangen, bis zur Eiablage in Gehegen untergebracht und dann wieder ausgesetzt. Die so gewonnenen Eier werden künstlich ausgebrütet und die geschlüpften Jungtiere verkauft.[15]

Die zunehmende Dürre der sich stetig ausbreitenden Sahelzone schränkt das Verbreitungsgebiet des Nördlichen Felsenpythons immer mehr ein.[2] Hinzu kommt die fortlaufende Umstrukturierung und Zerstörung von Habitaten durch den Menschen. Durch die stetig wachsende Ölindustrie Süd-Nigerias werden beispielsweise die vom Nördlichen Felsenpython bevorzugt bewohnten Mangrovenwälder ausgebeutet. Sprengungen, der Bau von Kanälen, Straßen und Pipelines beschränken und zerstören dieses Habitat fortlaufend. Obwohl dieser Python sehr anpassungsfähig ist und viele vom Menschen veränderte Areale bewohnen kann, ist sein Bestand in einigen Ländern rückläufig.[5]

Als gefährdet wird der Nördliche Felsenpython im Washingtoner Artenschutzübereinkommen in Anhang II gelistet und unterliegt daher Handelsbeschränkungen.[19]

Der Nördliche Felsenpython erhielt zu Ehren des deutsch-holländischen Naturaliensammlers Albert Seba seinen wissenschaftlichen Namen Python sebae.[3]

Die Verwandtschaftsbeziehungen zwischen den großen afrikanischen Pythons: Python sebae (Gmelin 1789), Python natalensis (Smith 1840) und Python saxuloides (Miller & Smith 1979)[20] waren lange Zeit ungeklärt. Es mangelte an Belegexemplaren für die einzelnen Arten, insbesondere von Orten, wo sie in Sympatrie oder Parapatrie vorkommen. Daher wurden diese Pythons im 20. Jahrhundert größtenteils nur als eine monotypische Art anerkannt und unter dem Namen Python sebae geführt.[17] Anhand einer großen Datensammlung grenzte Broadley 1984 Felsenpythons mit nördlicherem und südlicherem Verbreitungsgebiet voneinander ab, primär auf Basis der Fragmentierungsstärke der Kopfoberseitenschilde und auf Grund der Musterung der Kopfseite. Wegen allfälliger Hybridisierungen in Überschneidungsgebieten wies er den beiden Gruppen nur Unterartstatus zu und benannte die nördliche Form mit Python sebae sebae und die südliche Form mit Python sebae natalensis. Python saxuloides stellte sich als eine etwas abweichende kenianische Population von Python sebae natalensis heraus und wurde mit letzterem gleichgesetzt.[3] 1999 wies Broadley den beiden Unterarten Artstatus zu, da neue präzisere Daten aus Gebieten mit extensiver Sympatrie in Burundi, Kenia und Tansania auf keinerlei Hybridisierungen hinwiesen.[12] 2002 wurde jedoch von Mischlingen in der Nähe der tansanischen Stadt Morogoro berichtet.[8] Dennoch gilt die Einteilung in zwei separate Arten auf Grund der momentanen Datenlage noch als zutreffend. Es müssten weitere Belege für Hybridisierungen folgen oder eine genetische Analyse negativ ausfallen, um den Artstatus rückgängig zu machen.[17]

Unter den Eigentlichen Pythons sind der Nördliche und der Südliche Felsenpython am nächsten verwandt mit dem in Süd- und Südostasien beheimateten Tigerpython. Dies geht aus einer neueren molekulargenetischen Untersuchung hervor, die den Nördlichen Felsenpython und den Tigerpython einschließt.[21]

Wildlebende Nördliche Felsenpythons meiden die Konfrontation mit Menschen. Kommt ihnen ein Mensch zu nahe, versuchen sie gewöhnlich in ein Versteck oder ins Wasser zu flüchten.[5] Bei größerer Beunruhigung, besonders wenn sie in die Enge getrieben werden, gehen gewisse Tiere jedoch schnell zur Abwehr über und beißen mit ihren langen Vorderzähnen heftig und wiederholt zu, was zu tiefen infektiösen Wunden führt.[4] Einige Individuen lassen Menschen aber auch sehr nahe an sich herankommen und erstarren dabei nur oder kriechen langsam weg.[1] Es existieren wenige Berichte, wonach der Nördliche Felsenpython in der Wildnis Menschen attackiert und getötet haben soll. Seriöse Belege hierfür gibt es jedoch nicht.[7]

Schon in der Antike wurde dem Nördlichen Felsenpython Aufmerksamkeit geschenkt. So wussten die alten Griechen bereits mehrere Jahrhunderte v. Chr. von riesigen Schlangen in Nubien, betrachteten diese als typisch für die dortige Fauna und glaubten, dass sie teilweise sogar Elefanten fressen würden. Ptolemaios II., der von 282 bis 246 v. Chr. zweiter ptolemäischer König von Ägypten war, beauftragte extra eine zirka 100 Männer umfassende Gruppe aus Jägern, Reitern, Schleuderern, Trompetern und Bogenschützen, eine der größten dieser Schlangen zu fangen und lebendig in seine weithin berühmte Menagerie zu bringen. In Süd-Nubien, wo der Nördliche Felsenpython damals noch verbreitet war, soll es den Männern dann nach mehreren Anläufen gelungen sein, ein äußerst wehrhaftes Individuum mit einer Gesamtlänge von angeblich über 13 Meter zu fangen und dem König zu überbringen. Dieses „Biest“ wurde dann in der Menagerie gefüttert und gezähmt und galt als Ptolemaios’ II. außergewöhnlichstes und berühmtestes Tier. Der Nördliche Felsenpython war auch wiederholt das Sujet in Mosaiken. Im Nilmosaik von Palestrina, das um 200 v. Chr. entstand, wurde ein großer Python, der sich um einen Felsen schlängelt, und ein zweiter, der gerade am Nilufer einen Vogel erbeutet, dargestellt.[22] Auf einem weiteren Mosaik aus dem ehemaligen römischen Karthago, das zwischen dem zweiten und vierten Jahrhundert n. Chr. entstand, ist ein Python zu sehen, der mit einem Elefanten kämpft.[1]

Im alten Römischen Reich wurden während der Zirkusspiele oft Schlangen zur Schau gestellt. Dabei galten auch die teilweise gezähmten Nördlichen Felsenpythons als attraktiv.[23]

In einigen westafrikanischen Kulturen gab es vor der Kolonialisierung einen Schlangenkult. Insbesondere der Nördliche Felsenpython und der Königspython wurden als heilig betrachtet, in Schlangentempeln gehalten und verehrt. In Zeremonien überbrachte man dem Nördlichen Felsenpython zahlreiche Geschenke und stellte ihn mit dem Opfern eines Huhnes oder Lammes zufrieden.[23] Dieser Python hatte beispielsweise in Nigeria einen so hohen Stellenwert, dass schon einer der ersten Verträge zwischen englischen Invasoren und Stammesführern den Schutz dieser Schlangen regelte.[5] Bis heute wird diese Art in vielen Teilen ihres Verbreitungsgebietes vergöttert. Im Südsudan glauben beispielsweise die Völker der Dinka, Schilluk und Bari, dass bestimmte Einzeltiere Träger der Seelen Verstorbener sind. Diese Pythons genießen dort den allergrößten Respekt, werden mit Opfergaben beschenkt und es wird zu ihnen gebetet, um Elend, Krankheit, Dürren und Hungersnöte abzuwenden.[24] In einigen lokalen Gesellschaften ist der Glaube weit verbreitet, es werde nach dem Töten eines Nördlichen Felsenpythons kein Regen mehr fallen.[4] Manche Gruppen, darunter auch solche, die nur Einzelindividuen vergöttern, töten Nördliche Felsenpythons zu Nahrungszwecken und für die traditionelle Medizin.[24] Beispielsweise in der Demokratischen Republik Kongo werden sie hierfür mit Speeren gejagt oder am Eingang ihrer Verstecke mit Schlingfallen gefangen. Das Fleisch gilt als schmackhaft, dem Dorschfleisch ähnlich, und dem Pythonfett werden wundersame Heilkräfte zum Kurieren zahlreicher Krankheiten nachgesagt.[4]

Der Nördliche Felsenpython (Python sebae), auch kurz Felsenpython, zählt zur Familie der Pythons (Pythonidae) und wird dort in die Gattung der Eigentlichen Pythons (Python) gestellt. Er unterscheidet sich durch Beschuppungs- und Musterungsmerkmale vom Südlichen Felsenpython. Mit gesicherten Längen über fünf Meter gehört der Nördliche Felsenpython zu den größten Schlangen der Welt. Sein Verbreitungsgebiet erstreckt sich in Afrika südlich der Sahara von der Westküste bis zur Ostküste und südlich bis in den Norden von Angola. Hier bewohnt er eine Vielzahl tropischer und subtropischer Landschaften in nicht zu großer Entfernung von Gewässern. Er ist sehr anpassungsfähig und besiedelt als Kulturfolger auch landwirtschaftliche Nutzflächen und Siedlungen.

Die Nahrung besteht aus einer Vielzahl unterschiedlicher Wirbeltiere. In Gebieten mit hohen Säugerbeständen erbeuten große Individuen relativ häufig kleine Antilopen, die selten sogar über 30 Kilogramm schwer sein können. Der Python tötet seine Beute durch Erwürgen.

The Central African rock python (Python sebae) is a species of large constrictor snake in the family Pythonidae. The species is native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is one of 10 living species in the genus Python.

Africa's largest snake and one of the eight largest snake species in the world (along with the green anaconda, reticulated python, Burmese python, Southern African rock python, Indian python, yellow anaconda and Australian scrub python), specimens may approach or exceed 6 m (20 ft). The southern species is generally smaller than its northern relative but in general, the Central African rock python is regarded as one of the longest species of snake in the world.[3] The snake is found in a variety of habitats, from forests to near deserts, although usually near sources of water. The snake becomes dormant during the dry season. The Central African rock python kills its prey by constriction and often eats animals up to the size of antelope, occasionally even crocodiles. The snake reproduces by egg-laying. Unlike most snakes, the female protects her nest and sometimes even her hatchlings.

The snake is widely feared, though it is nonvenomous and very rarely kills humans. Although the snake is not endangered, it does face threats from habitat reduction and hunting. Some cultures in sub-Saharan Africa consider it a delicacy, which may pose a threat to its population.

The Central African rock python is in the genus Python, large constricting snakes found in the moist tropics of Asia and Africa.

P. sebae was first described by Johann Friedrich Gmelin, a German naturalist, in 1789.[4] Therefore, he is also the taxon author of the species.

The generic name Python is a Greek word referring to the enormous serpent at Delphi slain by Apollo in Greek mythology. The specific name sebae is a latinization of the surname of Dutch zoologist, Albertus Seba.[5][6] Common name usage varies with the species referred to as the African rock python or simply the rock python.

Africa's largest snake species[7][8] and one of the world's largest,[5] the Central African rock python adult measures 3 to 3.53 m (9 ft 10 in to 11 ft 7 in) in total length (including tail), with only unusually large specimens likely to exceed 4.8 m (15 ft 9 in). Reports of specimens over 6 m (19 ft 8 in) are considered reliable, although larger specimens have never been confirmed.[9][10][11] Weights are reportedly in the range of 55 to 65 kg (121 to 143 lb) or more.[12] Exceptionally large specimens may weigh 91 kg (201 lb) or more.[13][14][15] On average, large adults of Central African rock pythons are quite heavily built, perhaps more so than most specimens of the somewhat longer reticulated as well as Indian and Burmese pythons and far more so than the amethystine python, although the species is on average less heavily built than the green anaconda. The species may be the second heaviest living snake with some authors agreeing that it can exceptionally exceed 90 kg (200 lb).[16][17][18] One specimen, reportedly 7 m (23 ft 0 in) in length, was killed by K. H. Kroft in 1958 and was claimed to have had a 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) juvenile Nile crocodile in its stomach.[19] An even larger specimen considered authentic was shot in the Gambia and measured 7.5 m (24 ft 7 in).[10][11]

The snake varies considerably in body size between different areas. In general, it is smaller in highly populated regions, such as in southern Nigeria, only reaching its maximum length in areas such as Sierra Leone, where the human population density is lower. Males are typically smaller than females.[10]

The Central African rock python's body is thick and covered with colored blotches, often joining up in a broad, irregular stripe. Body markings vary between brown, olive, chestnut, and yellow, but fade to white on the underside.[20][8] The head is triangular and is marked on top with a dark brown “spear-head” outlined in buffy yellow. Teeth are many, sharp, and backwardly curved.[21][8] Under the eye, there is a distinctive triangular marking, the subocular mark.[20] Like all pythons, the scales of the African rock python are small and smooth.[8][22] Those around the lips possess heat-sensitive pits, which are used to detect warm-blooded prey, even in the dark.[21][22][23] Pythons also possess two functioning lungs, unlike more advanced snakes, which have only one, and also have small, visible pelvic spurs, believed to be the vestiges of hind limbs.[22][23]

The Southern African rock python and the Central African rock python differ in the following ways:

The Central African rock python is found throughout almost the whole of sub-Saharan Africa,[29] from Senegal east to Ethiopia and Somalia and south to Namibia and South Africa.[30][8] P. sebae ranges across central and western Africa, while P. natalensis has a more eastern and southerly range, from southern Kenya to South Africa.[7]

In 2009, a Central African rock python was found in the Florida Everglades.[31] It is feared to be establishing itself as an invasive species alongside the already-established Burmese python. Feral rock pythons were also noted in the 1990s in the Everglades.[9]

The Central African rock python inhabits a wide range of habitats, including forest, savanna, grassland, semidesert, and rocky areas. It is particularly associated with areas of permanent water,[20][32] and is found on the edges of swamps, lakes, and rivers.[7][8] The snake also readily adapts to disturbed habitats, so is often found around human habitation,[29] especially cane fields.[5]

Central African rock python, Senegal National Park

Like all pythons, the Central African rock python is non-venomous and kills by constriction.[21][23] After gripping the prey, the snake coils around it, tightening its coils every time the victim breathes out. Death is thought to be caused by cardiac arrest rather than by asphyxiation or crushing.[21] The African rock python feeds on a variety of large rodents, monkeys, warthogs, antelopes, vultures, fruit bats, monitor lizards, crocodiles, and more in forest areas,[8] and on rats, poultry, dogs, and goats in suburban areas. It will sometimes take fish as well.[33] Occasionally, it may eat the cubs of big cats such as leopards, lions, and cheetahs, cubs of hyenas, and puppies of wild dogs such as jackals and Cape hunting dogs.. However, these encounters are very rare, as the adult cats can easily kill pythons or fend them off.[34][11] On March 1, 2017, a 3.9-m (12-ft 10-in) African rock python was filmed eating a large adult male spotted hyena weighing 70 kg (150 lb). This encounter suggests that the snake might very well be capable of hunting and killing larger and more dangerous animals than previously thought.[35] The largest ever recorded meal of any snake was when a 4.9m African Rock Python consumed a 59-kg impala.[36]

Reproduction occurs in the spring.[5] Central African rock pythons are oviparious, laying between 20 and 100 hard-shelled, elongated eggs in an old animal burrow, termite mound, or cave.[7][8] The female shows a surprising level of maternal care, coiling around the eggs, protecting them from predators, and possibly helping to incubate them, until they hatch around 90 days later.[7][21][8] The female guards the hatchlings for up to two weeks after they hatch from their eggs to protect them from predators in a manner unusual for snakes in general and pythons in particular.[37]

Hatchlings are between 45 and 60 cm (17.5 and 23.5 in) in length and appear virtually identical to adults, except with more contrasting colors.[5] Individuals may live over 12 years in captivity.[38]

Documented attacks on humans are exceptionally rare, despite the species being common in many regions of Africa, and living in diverse habitats including those with agricultural activity.[29] Few deaths are well-substantiated, with no reports of a human being consumed.[29] Large specimens (which are more common in Western Africa) "would have no difficulty in eating adult humans",[29] though it would have to be a small adult human.

As the mammalian and avian game populations are gradually depleted in the Congo Basin, the proportion of large-bodied snakes offered at rural bushmeat markets increases. Consequently, a large proportion of the human population faces the threat of Armillifer armillatus infections, a python-borne zoonotic disease.[51]