pt-BR

nomes no trilho de navegação

Greater adjutants are large birds, ranging in height from 120 to 152 cm with an impressive 250 cm wingspan. A long, thick yellow bill precedes the sparsely feathered, yellow to pink head and neck. The head is typically dappled with dark scabs of dried blood and characterized by the presence of a pendulous, inflatable gular pouch. The legs are naturally dark in color but frequently appear ashen due to regular defecation on the legs. When in flight, greater adjutants are recognizable by their white underside feathers and tendency to retract their necks like a heron. A mixture of white and gray feathers, which appear darker during the non-breeding season, adorn the rest of the body. Juvenile greater adjutants resemble adults, but have duller plumage and more feathers around the neck. The mass of these birds is unknown in the wild, but is estimated to be the heaviest of the storks.

Range length: 120 to 152 cm.

Average wingspan: 250 cm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: sexes alike; ornamentation

Although the longest lifespan of a captive greater adjutant was 43 years, the longevity of these birds in the wild remains unknown.

Range lifespan

Status: captivity: 43 (high) years.

Greater adjutants (Leptoptilos dubius) have been observed in a variety habitats including marshes, lakes and jheels (shallow expansive lakes) as well as dry grasslands and fields. These birds are most frequently associated with slaughter houses and refuse sites near human settlements and were formerly common on the streets and rooftops of Calcutta. They typically nest in large trees and rock pinnacles near human settlements.

Habitat Regions: tropical ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: savanna or grassland ; forest

Aquatic Biomes: lakes and ponds; temporary pools

Wetlands: marsh

Other Habitat Features: urban ; suburban ; riparian

Greater adjutants (Leptoptilos dubius) are exceedingly rare in their range from Northern India to Indochina and may breed exclusively in the Brahmaputra Valley of Assam. In the early part of the 20th century, large breeding populations of greater adjutants were common throughout Northern India, Bangladesh, Nepal and Southern Vietnam.

Biogeographic Regions: oriental (Native )

In their native range, where they are primarily scavengers of large carrion, greater adjutants are known by the name "hargila," meaning bone swallower. They were once prevalent in Calcutta, where their tendency to consume human corpses left to rot in the streets was valued. One record indicates that a single greater adjutant effortlessly swallowed two buffalo vertebrae, measuring approximately 30 cm in length, in less than five minutes. Greater adjutants are most commonly found scavenging in mixed flocks near human garbage dumps or large carcasses. They can also be seen foraging independently near drying pools where they hunt insects, frogs, large fish, crustaceans and injured waterfowl. When foraging, greater adjutants use a method of tactile foraging where they hold their beaks open underwater and patiently wait for a prey item to swim between the open mandibles.

Animal Foods: birds; mammals; amphibians; fish; carrion ; insects; aquatic crustaceans

Primary Diet: carnivore (Scavenger )

Greater adjutants are important scavengers of large carrion and likely contribute to sanitation and disease control in the environment. Like many birds, greater adjutants are hosts to avian lice including Colpocephalum cooki and Ciconiphilus temporalis.

Ecosystem Impact: biodegradation

Commensal/Parasitic Species:

Greater adjutants are valuable scavengers of discarded human waste, including unburied corpses as well as other large carrion. This service may have a role in preventing the spread of disease.

Greater adjutants lack vocal muscles so they rely on unique behaviors and tactile forms of communication to interact with each other. Males often utilize beak clattering to advertise their territory and ward off other males. Males attract mates by presenting them with fresh twigs and later holding their beaks close to the female. Breeding pairs also perform head bobbing rituals that likely reinforce their pair-bond. Like all birds, greater adjutants perceive their environments through visual, auditory, tactile, and chemical stimuli.

Communication Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Many consider greater adjutants to be the most endangered stork in the world. Captive breeding programs have failed thus far, but efforts to protect natural habitats are active. Unfortunately, their tendency to nest near human settlements may prove fatal.

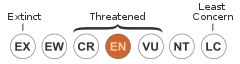

In the early part of the 20th century, the population size of greater adjutants is said to have numbered in the millions. They were common in Northern India, Bangladesh, Nepal and Southern Vietnam. Beginning in the mid 1980's the population began to decline heavily. Today an estimated 1,000 birds remain and likely breed only in the politically unstable Assam state of northern India. Populations are still declining and the IUCN red list lists greater adjutants as endangered.

Felling of large nesting trees, pollution of freshwater systems and a decline in the disposal of human corpses in public trash dumps are all thought to contribute to the rapid loss of this species. In Assam, recent reports of disease in this species also seems to be a contributing factor in its decline. Results of a survey of Assam residents revealed that only 30% of those polled knew greater adjutants are endangered. Greater community awareness of this unique species may help in its recovery.

CITES: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: endangered

While greater adjutants pose no threat to humans they are often looked upon with disgust because of their general appearance, habit of defecating on their own legs, as well as diet of carrion.

No natural predators have been reported for this species. Unhealthy or young birds are likely preyed upon by local carnivores.

Other storks are known to be monogamous, but not always paired for life. It is thought that greater adjutants follow this mating system. Great adjutants are colonial nesters and will build many nests in the canopy of a single tree. Males claim suitable nesting branches and advertise their territory by perching on the branch with bills upward and exhibiting bill-clattering. When females perch nearby, males will present them with twigs as part of courtship. Courtship rituals consist more of courtship postures, where males will hold their beaks close to potential mates or tuck the females heads under their chins. Pairs also perform up-down bobbing motions together.

Greater adjutants nest in large, broad-limbed trees with sparse foliage. This choice of nesting tree is thought to facilitate landing and take-off for the large adult birds. Nests are constructed out of sticks and several pairs will often occupy the same tree. While females lay 3 eggs per season, an average of 2.2 chicks per pair are fledged successfully each year. Both parents participate in incubating eggs until they hatch after 28 to 30 days. Chicks fledge at 5 months of age.

Breeding interval: Greater adjutants breed once a year.

Breeding season: Greater adjtants breed during the dry season from October to June.

Average eggs per season: 3.

Range time to hatching: 28 to 30 days.

Average fledging age: 5 months.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; oviparous

Both male and female greater adjutants participate in nest building. After the eggs are laid, both parents also incubate the clutch for 28 to 30. The altricial chicks are cared for by both parents until they fledge at 5 months old.

Parental Investment: altricial ; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Male, Female, Protecting: Male, Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Male, Female, Protecting: Male, Female); pre-independence (Provisioning: Male, Female, Protecting: Male, Female)

Ar marabou argala a zo un evn hirc'harek, Leptoptilos dubius an anv skiantel anezhañ.

Bevañ a ra al labous e biz India[1].

a vo kavet e Wikimedia Commons.

Ar marabou argala a zo un evn hirc'harek, Leptoptilos dubius an anv skiantel anezhañ.

El marabú caragroc[1] (Leptoptilos dubius) és un ocell de la família dels cicònids que hom pot observar en zones d'aiguamolls, cultius inundats, llacs i boscos poc densos al nord-est de l'Índia i Bangla Desh, Birmània, Tailàndia i Indoxina.[2]

El marabú caragroc (Leptoptilos dubius) és un ocell de la família dels cicònids que hom pot observar en zones d'aiguamolls, cultius inundats, llacs i boscos poc densos al nord-est de l'Índia i Bangla Desh, Birmània, Tailàndia i Indoxina.

Aderyn a rhywogaeth o adar yw Ciconia mawr India (sy'n enw gwrywaidd; enw lluosog: ciconiaid mawr India) a adnabyddir hefyd gyda'i enw gwyddonol Leptoptilos dubius; yr enw Saesneg arno yw Greater adjutant stork. Mae'n perthyn i deulu'r Ciconiaid (Lladin: Ciconiidae) sydd yn urdd y Ciconiformes.[1]

Talfyrir yr enw Lladin yn aml yn L. dubius, sef enw'r rhywogaeth.[2]

Mae'r ciconia mawr India yn perthyn i deulu'r Ciconiaid (Lladin: Ciconiidae). Dyma rai o aelodau eraill y teulu:

Rhestr Wicidata:

rhywogaeth enw tacson delwedd Ciconia Abdim Ciconia abdimii Ciconia amryliw Mycteria leucocephala Ciconia bach India Leptoptilos javanicus Ciconia du Ciconia nigra Ciconia gwyn Ciconia ciconia Ciconia gyddfwyn Ciconia episcopus Ciconia magwari Ciconia maguari Ciconia marabw Leptoptilos crumenifer Ciconia mawr India Leptoptilos dubius Ciconia melynbig Affrica Mycteria ibis Ciconia melynbig y Dwyrain Mycteria cinerea Ciconia pig agored Affrica Anastomus lamelligerus Ciconia pig agored Asia Anastomus oscitans Ciconia Storm Ciconia stormi Jabiru mycteria Jabiru mycteriaAderyn a rhywogaeth o adar yw Ciconia mawr India (sy'n enw gwrywaidd; enw lluosog: ciconiaid mawr India) a adnabyddir hefyd gyda'i enw gwyddonol Leptoptilos dubius; yr enw Saesneg arno yw Greater adjutant stork. Mae'n perthyn i deulu'r Ciconiaid (Lladin: Ciconiidae) sydd yn urdd y Ciconiformes.

Talfyrir yr enw Lladin yn aml yn L. dubius, sef enw'r rhywogaeth.

Marabu indický (Leptoptilos dubius) je velký pták z čeledi čápovitých. Patří do rodu Leptoptilos spolu s marabu africkým a marabu indomalajským.

Jižní a jihovýchodní Asie.

Marabu indický je 145–150 cm vysoký s rozpětím křídel cca 250 cm. Křídla jsou šedá a kontrastní s jinak černou horní stranou těla. Břicho a ocas jsou světle šedé, nohy jsou bílé. Olysalá hlava je růžová a mohutný zobák je žlutý.

Potrava se skládá z žab, velkého hmyzu, ještěrek a hlodavců, ale nepohrdne i mršinami a lidskými odpadky.

Žije v tropických mokřinách často v malých koloniích až s 30 hnízdy. Dvě až tři vajíčka jsou inkubována oběma rodiči po dobu 28–30 dnů.

![]() Galerie marabu indický ve Wikimedia Commons

Galerie marabu indický ve Wikimedia Commons

![]() Obrázky, zvuky či videa k tématu marabu indický ve Wikimedia Commons

Obrázky, zvuky či videa k tématu marabu indický ve Wikimedia Commons

Marabu indický (Leptoptilos dubius) je velký pták z čeledi čápovitých. Patří do rodu Leptoptilos spolu s marabu africkým a marabu indomalajským.

Adjudant (latin: Leptoptilos dubius) er en storkefugl, der lever i det nordøstlige Indien og det centrale Indokina.

Adjudant (latin: Leptoptilos dubius) er en storkefugl, der lever i det nordøstlige Indien og det centrale Indokina.

Der Große Adjutant oder Argala-Marabu (Leptoptilos dubius) ist ein großer Schreitvogel aus der Familie der Störche. Im Verbreitungsgebiet wird er (auch) Hargila genannt.

Der Große Adjutant wird 145–150 cm lang und hat eine Flügelspannweite von 250 cm. Die grauen großen Oberflügeldecken und Schirmfedern kontrastieren deutlich zur ansonsten schwarzen Oberseite. Bauch und Schwanzunterseite sind hellgrau, die Halskrause ist weiß. Der unbefiederte Kopf ist rosa und der mächtige Schnabel gelb gefärbt.

Während der Große Adjutant früher in Südasien von Indien und Sri Lanka bis nach Borneo brütete, beschränkt sich heute das Brutgebiet auf Assam und Kambodscha. Der Vogel überwintert in Vietnam, Thailand und Myanmar. Er besiedelt Seeufer und Salzwassersümpfe, aber auch lichte Wälder und trockene Graslandschaften.

Die Nahrung besteht aus Fröschen, großen Insekten, Jungvögeln, Eidechsen und Nagern, aber auch Aas und menschlicher Müll werden von diesem Storch nicht verschmäht. Der Große Adjutant brütet in tropischen Feuchtgebieten oft in kleinen Brutkolonien mit bis zu 30 Nestern. Zwei bis drei Eier werden von beiden Elternvögeln 28–30 Tage bebrütet.

Während der Vogel im 19. Jahrhundert in Indien und Birma häufig war, ist die Zahl heute auf weniger als 1000 Tiere zurückgegangen. Gründe dafür sind die Zerstörung von Brut- und Futtergebieten durch Trockenlegung von Feuchtgebieten, Einsatz von Pestiziden, sowie Bejagung und das Sammeln von Eiern.

Der Große Adjutant oder Argala-Marabu (Leptoptilos dubius) ist ein großer Schreitvogel aus der Familie der Störche. Im Verbreitungsgebiet wird er (auch) Hargila genannt.

धेनुक (अंगरेजी: Greater adjutant, बै॰:Leptoptilos dubius) चिरइन के स्टॉर्क परिवार के एगो प्रजाति बाटे।

राजगरुड नेपालमा पाइने एक प्रकारको चराको प्रजाति हो। यो चरालाई एक भ्रमणकारी चराका रूपमा पनि लिन सकिन्छ। यो प्रकारको चराहरूको मुख्य बसोबासको क्षेत्रका रूपमा एसिया तथा अफ्रिका लाई लिन सकिन्छ। यो जातिको चराको सबैभन्दा ठूलो बसोबास क्षेत्रका रूपमा भारतलाई लिन सकिन्छ। भारतको आसाममा निकै ठूलो सङ्ख्यामा रहेको यस राजगरुड जातिको चरा भारतकै बगलपुरमा पनि लगभग ४०० को दरमा रहेको छ। यस्तै कम्बोडियामा समेत राजगरुडको सङ्ख्या केही रूपमा वृद्धि हुँदै गइरहेको छ।

राजगरुड एउटा ठूलो शारीरिक बनोट हुने विशाल खाले चरा हो। यस चराको औसत उचाइ लगभग १४५–१५० सेमी (५७–५९ इन्च) हुने गर्दछ। भने औसत लम्बाई १३६ सेमी (५४ इन्च) हुने गर्दछ। यस्तै यो चरा उड्ने क्रममा पखेता फिजाउँदा २५० सेमी (९८ इन्च) लामो हुने गर्दछ। यस राजगरुडको औसत तौल लगभग ८ बाट ११ किग्रा (१८ बाट २४ पाउन्ड) जति हुने गर्दछ।

राजगरुड नेपालमा पाइने एक प्रकारको चराको प्रजाति हो। यो चरालाई एक भ्रमणकारी चराका रूपमा पनि लिन सकिन्छ। यो प्रकारको चराहरूको मुख्य बसोबासको क्षेत्रका रूपमा एसिया तथा अफ्रिका लाई लिन सकिन्छ। यो जातिको चराको सबैभन्दा ठूलो बसोबास क्षेत्रका रूपमा भारतलाई लिन सकिन्छ। भारतको आसाममा निकै ठूलो सङ्ख्यामा रहेको यस राजगरुड जातिको चरा भारतकै बगलपुरमा पनि लगभग ४०० को दरमा रहेको छ। यस्तै कम्बोडियामा समेत राजगरुडको सङ्ख्या केही रूपमा वृद्धि हुँदै गइरहेको छ।

হাড়গিলা (ইংৰাজী: Greater Adjutant, বৈজ্ঞানিক নাম: Leptoptilos dubius) চিক'নিডি (Ciconiidae) পৰিয়ালৰ অন্তৰ্ভুক্ত বগলী জাতীয় এবিধ চৰাই৷ পূৰ্বতে ইয়াক সমগ্ৰ দক্ষিণ এছিয়াতে পোৱা গৈছিল যদিও বৰ্তমান বিভিন্ন কাৰণত ইয়াৰ জনসংখ্যা হ্ৰাস পাই মাত্ৰ দুটা প্ৰজনন কাৰী গোটত বৰ্ত্তি আছে৷ তাৰে এটা ভাৰতৰ অসমত আৰু আনটো কম্বোডিয়া (Cambodia)ত আছে৷ হাড়গিলাৰ আকাৰ যথেষ্ট ডাঙৰ, ঠোঁটৰ আকাৰো বৃহৎ, মূৰটৌ নোমহীন আৰু ডিঙিত এটা বৈশিষ্ট্যপূৰ্ণ টোপোলা (neck pouch) থাকে৷ ইহঁতে মিলিটেৰী আৰ্হিত দিয়া খোজৰ লগত সাদৃশ্য ৰাখি ইয়াৰ ইংৰাজী নামটো উদ্ভৱ হৈছে৷ বৰ্তমান ইয়াৰ ক্ৰমান্বয়ে হৰাস পাই অহা জনসংখ্যালৈ লক্ষ্য ৰাখি ইয়াক সংকটাপন্ন প্ৰজাতি (endangered) বুলি আখ্যা দিয়া হৈছে৷ 2008 চনৰ পিয়ল অনুসৰি ইয়াৰ জনসংখ্যা এহাজাৰ মান বুলি ঠাৱৰ কৰা হৈছে৷

হাড়গিলা এটা বৃহৎ আকাৰৰ চৰাই৷ ইয়াৰ উচ্চতা প্ৰায় ১৪৫-১৫০ ছে: মি:৷ ইয়াৰ দেহৰ গড় দৈৰ্ঘ্য প্ৰায় ১৩৬ ছে: মি: আৰু ডেউকা প্ৰায় ২৫০ ছে: মি: হয়৷ [4] হাড়গিলাৰ বৃহৎ ঠোঁটৰ দৈৰ্ঘ্য প্ৰায় ৩২.২ ছে:মি: আৰু ৰং শেঁতা মুগা বৰণৰ হয়৷[5] হাড়গিলাৰ হালধীয়া বা ৰঙচুৱা ডিঙিৰ গুৰিতে থকা বগা বৰণৰ কলাৰৰ দৰে অংশটোৰ বাবে ইয়াক দেখাত শগুণৰ দৰে লাগে৷ প্ৰজননৰ কালত ডিঙি আৰু তাত থকা টোপোলাটো উজ্জ্বল কমলা বৰণৰ আৰু মটিয়া ঠেং দুখনো ৰঙচুৱা হৈ পৰে৷ পূৰ্ণবয়স্ক হাড়গিলাৰ সৰু পাখিবোৰ পাতল মটিয়া আৰু ডেউকা ডাঠ ৰঙৰ৷ ইয়াৰ দেহৰ তলৰ অংশ বগা বৰণৰ আৰু মতা-মাইকীৰ মাজত বিশেষ পাৰ্থক্য দেখা পোৱা নাযায়৷ পোৱালী হাড়গিলাবোৰ পূৰ্ণবয়স্ক চৰাইতকৈ শেঁতা বৰণৰ হয়৷ ডিঙিৰ টোপোলাটোৱে ইহঁতক শ্বাস-প্ৰশ্বাসত সহায় কৰে৷ পাচক তন্ত্ৰৰ লগত ইয়াৰ কোনো সম্পৰ্ক নাই৷ হাড়গিলাৰ লগত প্ৰায়েই সামঞ্জস্য দেখা পোৱা অন্যবিধ চৰাইৰ প্ৰজাতি হ'ল বৰটোকোলা ( Lesser Adjutant), টোপোলা নাথাকে৷ [6][7][8]

অন্যন্য বগলী জাতীয় চৰাইৰ দৰেই হাড়গিলাৰ শব্দৰ মাংসপেশী (vocal muscles) নাথাকে আৰু সেইবাবে ই কেৱল ঠোঁটেৰে শব্দ সৃষ্টি কৰিব পাৰে৷ [2][8][9]

জন লাথাম (John Latham) নামৰ পক্ষীবিদ গৰাকীয়ে তেওঁৰ ১৭৭৩ চনত প্ৰকাশ পোৱা 'ভয়েজ টু ইণ্ডিয়া' ("Voyage to India") নামৰ গ্ৰন্থত কলকাতা দেখা পোৱা চৰাই সমূহৰ বৰ্ণনা দিছীল আৰু ইয়াতে পোনপ্ৰথমে হাড়গিলাৰ উল্লেখ পোৱা যায়৷ এই ভ্ৰমণৰ ভিত্তিতে তেওঁ "General Synopsis of Birds"নামৰ গ্ৰন্থ খনত হাড়গিলাকো অন্তৰ্ভুক্ত কৰিছিল৷ লাথামে ইয়াক 'Gigantic Crane' বুলি অভিহিত কৰিছিল আৰু স্মিথমেন (Smeathman) নামৰ এগৰকী আফ্ৰিকান ভ্ৰমণকাৰীয়ে পশ্চিম আফ্ৰিকাত দেখা পোৱা একেধৰণৰ এবিধ চৰাইৰ বৰ্ণনাও ইয়াত অন্তৰ্ভুক্ত কৰিছিল৷ জ'হান ফ্ৰেডৰিক মেলিন (Johann Friedrich Gmelinএ লাথামৰ এই বৰ্ণনাৰ আধাৰত ভাৰতীয় চৰাইবিধক ১৭৮৯ চনত Ardea dubia নামেৰে অভিহিত কৰে৷ অৱশ্যে পৰৱৰ্ত্তী সময়ত লাথামে Ardea argala নামলৈ ইয়াক সলনি কৰে৷ কনৰাড জেকব টেমিন্কে (Temminck) এ আকৌ ১৮২৪ চনত এই নামটো সলাই চেনিগাল (Senegal) ত আফ্ৰিকাত পোৱা একেধৰণৰ চৰাইবিধৰ বাবে ব্যৱহাৱ কৰা নাম অনুযায়ী Ciconia marabou নামটো প্ৰৱৰ্ত্তন কৰে৷ পিছলৈ ইয়াক ভাৰতৰ বৰটোকোলাৰ বাবেও ব্যৱহাৰ কৰিবলৈ লয়৷ কিন্তু ই ভাৰতীয় আৰু আফ্ৰিকান চৰাইৰ প্ৰজাতি দুটাৰ সম্পৰ্কত ষথেষ্ট বেমেজালিৰ সৃষ্টি কৰে৷ [10][11] যদিও আফ্ৰিকাৰ মাৰাবাও ষ্টৰ্ক (Marabou Stork) নামৰ চৰাইবিধৰ দেখাত হাড়গিলাৰ সৈতে কিছু মিল আছে ইয়াৰ ঠোঁটৰ গঠন, গাৰ বৰণ আৰু প্ৰদৰ্শনৰ আচৰণ ইত্যদিয়ে ইয়াক পৃথক প্ৰজাতি বুলিহে অধিক তথ্য প্ৰদান কৰে৷ [12]

প্ৰায়ভাগ বগলী জাতীয় চৰায়ে ডিঙি মেলি উৰে কিন্তু হাড়গিলাই ইয়াৰ ডিঙি কিছু কোঁচ খুৱাইহে উৰে৷ [8] খোজ কঢ়াৰ সময়ত ই পোন হৈ মিলিটেৰী কায়দাত লৰচৰ কৰে বাবে ইয়াৰ ইংৰাজী নামত "adjutant" শব্দটো যোগ হ'ল৷[6]

হাড়গিলা এসময়ত উত্তৰ ভাৰতৰ নদীকাষৰীয়া অঞ্চল সমূহত উভৈনদীকৈ আছিল যদিও ইহঁতৰ বিতৰণ সম্পৰ্কে বহুদিনলৈকে কোনো প্ৰমাণ্য তথ্য নাছিল৷ ১৮৭৭ চনত ম্যনমাৰত পেগু (Pegu) ত এটা বৃহৎ হাড়গিলাৰ কলনি (nesting colony) আৱিস্কাৰ হয়৷ ই প্ৰমাণ কৰে ভাৰতীয় চৰাইবিধে তাতো বাহ সাজি পোৱালি জগায়৷ [13][14] দুখৰ বিষয়, এই কলনিটোৰ জনসংখ্যা ক্ৰমাৎ হ্ৰাস পাবলৈ ধৰে আৰু ১৯৩০ৰ আশে পাশে ই সম্পূৰ্ণ নোহোৱা হৈ যায়৷ [15] তাৰ পিছৰ পৰা অন্য নতুন ঠাই আৱিস্কৃত হোৱাৰ পুৰ্বলৈকে কাজিৰঙা ৰাষ্ট্ৰীয় উদ্যান ত পোৱা বাহ সজা অঞ্চলটোকে হাড়গিলাৰ একমাত্ৰ আশ্ৰয়স্থলী বুলি গণ্য কৰা হৈছিল৷ ১৯৮৯ চনৰ পিয়ল মতে অসমত হাড়গিলাৰ জনসংখ্যা আছিল ১১৫ টা চৰাই৷ [15][16][17][18] ১৯৯৪ ৰ পৰা ১৯৯৬ পৰ্যন্ত ব্ৰহ্মপুত্ৰ উপত্যকাত হাড়গিলাৰ জনসংখ্যা ৬০০ বুলি ধাৰণা কৰা হৈছিল৷ [19][20] ২০০৬ চনতভগলপুৰ ৰ ওচৰত হাড়গিলাৰ এটা সৰু কলনি আৱিস্কৃত হৈছে৷ [1][21]

প্ৰজনন নোহোৱা কাল (non-breeding season)ত হাড়গিলাই যথেষ্ট অঞ্চললৈ পৰিভ্ৰমণ কৰে৷ [22] ১৮০০ ৰ সময়ত গ্ৰীষ্ম কালত কলকাতা নগৰৰ আশে পাশে প্ৰায়ে হাড়গিলাৰজাক দেখা গৈছিল বুলি জনা যায়৷ কিন্তু ১৯০০ৰ আশে পাশে ই এই অঞ্চল সমূহৰ পৰা সম্পুৰ্ণকৈ বিলুপ্ত হৈ পৰিল৷ হাড়গিলাৰ বিলুপ্তিত স্থাস্থ্যসন্মত নিস্কাষণ (sanitation)ও অন্যতম কাৰণ বুলি ধাৰণা কৰা হয়৷ [7][8][23]

হাড়গিলা সাধাৰণতে অকলশৰে বা সৰু গোটত বাস কৰে৷ ই প্ৰধানকৈ কম পানী থকা বিলম হ্ৰদ আদি বা জাবৰৰ দ'মত খাদ্যৰ সন্ধান কৰে৷ ইয়াক প্ৰায়ে চিলনী বা শগুণৰ সৈতে চৰি ফুৰা দেখা যায়৷ [8] ই উষ্ণতা নিয়ন্ত্ৰণৰ বাবে ডেউকা দুখন কেতিয়াবা মেলি থৈ দিয়ে৷ [25]

শীতকাল ত হাড়গিলাই ডাঙৰ কলনিত গোট খাই খাদ্যৰ সন্ধান কৰে আৰু বাহ সাজে ৷ ইয়াৰ বাহৰ আকাৰ ডাঙৰ আৰু ই প্ৰধানকৈ গছৰ ডালিৰে গঠিত হয়৷ [13] অসমৰ নগাওঁ ত থকাহাড়গিলাৰ বাহবোৰ প্ৰধানত ওখ Alstonia scholaris আৰু Anthocephalus cadamba গছত আছে৷ [26] প্ৰজনন কালৰ আৰম্ভণিতে কেইবাটাও হাড়গিলা চৰায়ে লগ হৈ গছত বাহ সজাৰ স্থানৰ বাবে ইটোৱে সিটোৰ পৰা ঠাই অধিকাৰ কৰাৰ চেষ্টা কৰে৷ বিজয়ী মতা চৰাইটোৱে নিজৰ বাহৰ অধিকাৰ ক্ষেত্ৰ (nesting territories)ৰ চিন ৰাখে আৰু আনবোৰক খেদি পঠিয়ায়৷ ওচৰে পাজৰে মাইকী হাড়গিলা এজনীৰ আগমণ হ'লে মতাটোৱে সতেজ গছৰ ডালি আনি মাইকী জনীৰ সন্মুখত থয়হি৷ নাইবা মতা চৰাইটোৱে কেতিয়াবা মাইকী জনীৰ ঠেঙত নিজৰ ঠোঁট লগাই দিয়ে বা মাইকী জনীৰ ঠোঁট ত নিজৰটো লগাই দিয়ে৷ পশন্দ হ'লে মাইকী চৰাইজনীয়ে নিজৰ ঠোঁটটো আৰু মূৰ মতা টোৰ বুকুৰ কাষত ৰাখে৷ অন্যান্য প্ৰদৰ্শনবোৰ হ'ল মতা আৰু মাইকী হাড়গিলাই একেলগে ঠোঁট ওপৰ তল কৰা৷ এবাৰত ৩-৪ টা কণী পাৰে৷ [13]মতা-মাইকী উভয়ে মিলি উমনি দিয়ে৷ [27]

হাড়গিলা এবিধ সৰ্বভক্ষী (omnivorous) চৰাইৰ প্ৰজাতি৷ ইয়াৰ প্ৰধান খাদ্যৰ ভিতৰত ভেকুলী, পোক-পতংগ,চৰাই, সৰীসৃপ আৰু নিগনি আদিয়ে প্ৰধান৷ তাৰোপৰি ই বনৰীয়া হাঁহজাতীয় চৰাইক আক্ৰমণ কৰি গপোটেগোটে গিলি খোৱাৰো তথ্য পোৱা যায়৷ [28] অৱশ্যে ই প্ৰধানকৈ মৰা জীৱ-জন্তু খাই জীয়াই থাকে আৰু তাৰ বাবে ইয়াৰ উদং মূৰ আৰু ডিঙি বিশেষভাৱে অভিযোজিত৷ ইহঁতক প্ৰায়ে জাৱৰৰ দ'মত দেখা যায়, ই তাৰ পৰা মানুহ বা অন্য জীৱ-জন্তুৰ মল খাই জীয়াই থাকে৷ [29] ১৯ শতিকাত কলকাতা চহৰত ইহঁতে গংগাত বিসৰ্জন দিয়া মানুহৰ মৰাশও খোৱা বুলি জনা যায় ৷ [30]

জলাশয় সমূহ শুকাই যোৱাৰ ফলত বাহ সজাৰ আৰু চৰাৰ স্থানৰ অভাৱত তথা প্ৰদুষণ আদিৰ প্ৰভাৱত হাড়গিলাৰ জনসংখ্যা বিপদজনক ভাৱে হ্ৰাস পাই আহিছে৷ ২০০৮ চনত সমগ্ৰ বিশ্বতে আহাজাৰতকৈ কম হাড়গিলা আছে বুলি জনা গৈছে৷ সেয়ে আই.ইউ. চি. এনৰ ৰেড লিষ্টত ইয়াক সংকটাপন্ন প্ৰজাতি ( Endangered) বুলি আখ্যা দিয়া হৈছে৷ [1]

বৰ্তমান হাতত লোৱা বিভিন্ন ধৰণৰ সংৰক্ষণৰ পসক্ষেপ সমূহৰ ভিতৰত কৃত্ৰিম পৰিৱেশত প্ৰজননৰ ব্যৱস্থা , পোৱালীৰ মৃত্যুৰ হাৰ হ্ৰাস কৰা ইত্যদি উল্লেখযোগ্য৷ [31][32] তথ্য অনুসৰি বাহৰ পৰা তললৈ পৰি অনাহাৰত প্ৰায় ১৫% পোৱালিৰ মৃত্যু হয়৷ ইয়াক ৰোধ কৰিবলৈও প্ৰকৃতিপ্ৰেমী সকলে বিশেষ ব্যৱস্থা হাতত লৈছে৷ [4]

এসময়ত কলকাতাত হাড়গিলাক পাকৈত জামাদাৰ বুলি গণ্য কৰা হৈছিল আৰু ইয়াক চিকাৰ কৰিকে পঞ্চাছ টকাৰ জৰিমণা বিহাৰ ব্যৱস্থা কৰি এখন আইনো বলবৎ কৰা হৈছিল৷ [33][34][35] কলকাতা মিউনিচিপাল কৰপৰেশ্যনৰ পূৰ্বৰ প্ৰতীকচিহ্নত দুটা হাড়গিলা চৰাই মূখামুখিকৈ থকা প্ৰতিচ্ছবি আছিল৷ [36]

মোগলৰ ৰাজত্ব কালত গঢ় লোৱা এটা জনশ্ৰুতি মতে হাড়গিলাৰ খোলাৰ ভিতৰত এটা যাদুকৰী সাপ মৰা শিল আছে যাৰ সহায়ত সকলো সাপৰ বিষকে নোহোৱা কৰিব পৰা যায়৷ [6][37] এই বিশেষ শিলটো পাকৈত চিকাৰীয়ে হে আহৰণ কৰিব পাৰে বিলি ধাৰণা কৰা হৈছিল কাৰণ ইয়াক পাবৰে বাবে হাড়গিলা চৰাইটোৰ ঠোঁটে ভূমি স্পৰ্শ নকৰাকৈ মাৰিব লাগে৷ তাৰোপৰি পানৰ সৈতে হাড়গিলা মাংস নিয়মীয়াকৈ খালে কুষ্ঠৰোগৰো নিৰাময় হয় বুলি জনমানসত বিশ্বাস আছিল৷ [38]

হাড়গিলা (ইংৰাজী: Greater Adjutant, বৈজ্ঞানিক নাম: Leptoptilos dubius) চিক'নিডি (Ciconiidae) পৰিয়ালৰ অন্তৰ্ভুক্ত বগলী জাতীয় এবিধ চৰাই৷ পূৰ্বতে ইয়াক সমগ্ৰ দক্ষিণ এছিয়াতে পোৱা গৈছিল যদিও বৰ্তমান বিভিন্ন কাৰণত ইয়াৰ জনসংখ্যা হ্ৰাস পাই মাত্ৰ দুটা প্ৰজনন কাৰী গোটত বৰ্ত্তি আছে৷ তাৰে এটা ভাৰতৰ অসমত আৰু আনটো কম্বোডিয়া (Cambodia)ত আছে৷ হাড়গিলাৰ আকাৰ যথেষ্ট ডাঙৰ, ঠোঁটৰ আকাৰো বৃহৎ, মূৰটৌ নোমহীন আৰু ডিঙিত এটা বৈশিষ্ট্যপূৰ্ণ টোপোলা (neck pouch) থাকে৷ ইহঁতে মিলিটেৰী আৰ্হিত দিয়া খোজৰ লগত সাদৃশ্য ৰাখি ইয়াৰ ইংৰাজী নামটো উদ্ভৱ হৈছে৷ বৰ্তমান ইয়াৰ ক্ৰমান্বয়ে হৰাস পাই অহা জনসংখ্যালৈ লক্ষ্য ৰাখি ইয়াক সংকটাপন্ন প্ৰজাতি (endangered) বুলি আখ্যা দিয়া হৈছে৷ 2008 চনৰ পিয়ল অনুসৰি ইয়াৰ জনসংখ্যা এহাজাৰ মান বুলি ঠাৱৰ কৰা হৈছে৷

ਬਢੀੰਗ (en:greater adjutant) (Leptoptilos dubius) ਇੱਕ ਸਾਰਸ ਸ਼੍ਰੇਣੀ ਦਾ ਪੰਛੀ ਹੈ।ਇਸਨੂੰ ਗਿਲੜ੍ਹ ਵੀ ਕਿਹਾ ਜਾਂਦਾ ਹੈ।

ਬਢੀੰਗ (en:greater adjutant) (Leptoptilos dubius) ਇੱਕ ਸਾਰਸ ਸ਼੍ਰੇਣੀ ਦਾ ਪੰਛੀ ਹੈ।ਇਸਨੂੰ ਗਿਲੜ੍ਹ ਵੀ ਕਿਹਾ ਜਾਂਦਾ ਹੈ।

பெருநாரை[3] (Greater Adjutant, Leptoptilos dubius) என்பது பெயருக்கு ஏற்றபடியே நாரைக் குடும்பத்தைச் சேர்ந்த பெரிய பறவையாகும். இவை ஒரு காலத்தில் தெற்காசியா முழுவதும் (குறிப்பாக இந்தியாவில்) பரவலாக காணப்பட்டன. ஆனால், தற்போது இந்தியாவின் கிழக்கிலிருந்து போர்னியோ வரை காணப்படுகின்றன. இவை இந்தியாவில் குறிப்பிடும்படியாக அசாத்தில் காணப்படுகின்றன. இவற்றின் அலகுகள் மஞ்சள் நிறத்தில் ஆப்புப் போன்ற நான்குபக்க வடிவில் இருக்கும். இதன் நெஞ்சில் ஒரு தனித்துவமான செந்நிறப் பை தனித்த அடையாளமாக உள்ளது. இந்தப் பை மூச்சுடன் சம்பந்தப்பட்ட காற்றுப்பையாகும். இவை சிலசமயம் இறந்த விலங்குகளை உண்ணும் கழுகுகளுடன் இணைந்து உணவு உண்ணும். இவை தரையில் நடக்கும் போது சிப்பாய் போல மிடுக்குடன் நடக்கும்.

இப்பறவைகள் 145-150 செ. மீ. (57-60 அங்குலம்) உயரம் உள்ளவை. சராசரி நீளம் 136 செ.மீ (54 அங்குலம்) ஆகும். இறகு விரிந்த நிலையில் 250 செ. மீ. (99 அங்குலம்) அகலம் இருக்கும். சிவப்பு நிறமுள்ள கழுத்தும் முடிகளற்ற, செந்நிறத் தலையும் கொண்ட இவற்றின் மேற்புறம் அழுக்குக் கருப்பு நிறத்திலும் கீழ்புறம் அழுக்கு வெள்ளை நிறத்திலும் இருக்கும். இதனுடைய கூடுகளை உயர்ந்த பாறை இடுக்குகளிலோ உயர்ந்த மரங்களின் மீதோ கட்டும்.

பெருநாரை (Greater Adjutant, Leptoptilos dubius) என்பது பெயருக்கு ஏற்றபடியே நாரைக் குடும்பத்தைச் சேர்ந்த பெரிய பறவையாகும். இவை ஒரு காலத்தில் தெற்காசியா முழுவதும் (குறிப்பாக இந்தியாவில்) பரவலாக காணப்பட்டன. ஆனால், தற்போது இந்தியாவின் கிழக்கிலிருந்து போர்னியோ வரை காணப்படுகின்றன. இவை இந்தியாவில் குறிப்பிடும்படியாக அசாத்தில் காணப்படுகின்றன. இவற்றின் அலகுகள் மஞ்சள் நிறத்தில் ஆப்புப் போன்ற நான்குபக்க வடிவில் இருக்கும். இதன் நெஞ்சில் ஒரு தனித்துவமான செந்நிறப் பை தனித்த அடையாளமாக உள்ளது. இந்தப் பை மூச்சுடன் சம்பந்தப்பட்ட காற்றுப்பையாகும். இவை சிலசமயம் இறந்த விலங்குகளை உண்ணும் கழுகுகளுடன் இணைந்து உணவு உண்ணும். இவை தரையில் நடக்கும் போது சிப்பாய் போல மிடுக்குடன் நடக்கும்.

The greater adjutant (Leptoptilos dubius) is a member of the stork family, Ciconiidae. Its genus includes the lesser adjutant of Asia and the marabou stork of Africa. Once found widely across southern Asia and mainland southeast Asia, the greater adjutant is now restricted to a much smaller range with only three breeding populations; two in India, with the largest colony in Assam, a smaller one around Bhagalpur; and another breeding population in Cambodia. They disperse widely after the breeding season. This large stork has a massive wedge-shaped bill, a bare head and a distinctive neck pouch. During the day, it soars in thermals along with vultures with whom it shares the habit of scavenging. They feed mainly on carrion and offal; however, they are opportunistic and will sometimes prey on vertebrates. The English name is derived from their stiff "military" gait when walking on the ground. Large numbers once lived in Asia, but they have declined (possibly due to improved sanitation) to the point of endangerment. The total population in 2008 was estimated at around a thousand individuals. In the 19th century, they were especially common in the city of Calcutta, where they were referred to as the "Calcutta adjutant" and included in the coat of arms for the city. Known locally as hargila (derived from the Assamese words "har" means bone and "gila" means swallower, thus "bone-swallower") and considered to be unclean birds, they were largely left undisturbed but sometimes hunted for the use of their meat in folk medicine. Valued as scavengers, they were once depicted in the logo of the Calcutta Municipal Corporation.

The greater adjutant was described in 1785 by the English ornithologist John Latham as the "giant crane" in his book A General Synopsis of Birds. Lathan based his own description on that given by Edward Ives in his A Voyage from England to India that was published in 1773. Ives had shot a specimen near Calcutta. In his account Latham also mentioned that he had learned from the traveller Henry Smeathman that a similar species was found in Africa.[4][5] When in 1789 the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin revised and expanded Carl Linnaeus's Systema Naturae, he included the greater adjutant, coined the binomial name Ardea dubia and cited Latham's work.[6] Gmelin did not mention the coloured plate of the bird that Latham included in his 1787 Supplement to the General Synopsis of Birds. Latham based his plate on a drawing in the collection of Lady Impey that had been made of a live bird in India.[7]

There was some confusion as to whether the African marabou stork represented a separate species. In 1790 Latham in his Index Ornithologicus repeated his earlier description of the Indian species but gave the location as Africa and coined the binomial name Ardea argala.[8] Finally, in 1831 the French naturalist René Lesson described the differences between the two species and coined Circonia crumenisa for the marabou stork.[9][10]

The greater adjutant is now placed with the lesser adjutant and the marabou stork in the genus Leptoptilos that was introduced in 1831 by the French naturalist René Lesson.[11][12] The species is monotypic: no subspecies are recognised.[12]

The marabou stork of Africa looks somewhat similar but their disjunct distribution ranges, differences in bill structure, plumage, and display behaviour support their treatment as separate species.[13]

Most storks fly with their neck outstretched, but the three Leptoptilos species retract their neck in flight as herons do, possibly due to the heavy bill.[14] When walking on the ground, it has a stiff marching gait from which the name "adjutant" is derived.[15]

The greater adjutant is a huge bird, standing tall at 145–150 cm (4 ft 9 in – 4 ft 11 in). The average length is 136 cm (4 ft 6 in) and average wingspan is 250 cm (8 ft 2 in), it may rival its cousin the marabou stork (Leptoptilos crumeniferus) as the largest winged extant stork.[16] While no weights have been published for wild birds, the greater adjutant is among the largest of living storks, with published measurements overlapping with those of the jabiru (Jabiru mycteria), saddle-billed stork (Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis) and marabou stork (Leptoptilos crumeniferus). Juvenile greater adjutant storks in captivity weighed from 8 to 11 kg (18 to 24 lb).[17] A greater adjutant after recuperating in captivity from after injury during nest collapse was found to weigh 4.71 kg (10.4 lb) as a nestling and to weigh 8 kg (18 lb) after reaching maturity and ready for re-release.[18] For comparison, the heaviest known wild stork was a marabou stork scaling 8.9 kg (20 lb), with adult marabou ranging from 4–6.8 kg (8.8–15.0 lb) (females) and 5.6–8.9 kg (12–20 lb) (males).[19][20] The huge bill, which averages 32.2 cm (12.7 in) long, is wedge-like and is pale grey with a darker base. The wing chord averages 80.5 cm (31.7 in), the tail 31.8 cm (12.5 in) and the tarsus 32.4 cm (12.8 in) in length. With the exception of the tarsus length, the standard measurements of the greater adjutant are on average greater than that of other stork species.[21] A white collar ruff at the base of its bare yellow to red-skinned neck gives it a vulture-like appearance. In the breeding season, the pouch and neck become bright orange and the upper thighs of the grey legs turn reddish. Adults have a dark wing that contrasts with light grey secondary coverts. The underside of the body is whitish and the sexes are indistinguishable in the field. Juveniles are a duller version of the adult. The pendant inflatable pouch connects to the air passages and is not connected to the digestive tract. The exact function is unknown, but it is not involved in food storage as was sometimes believed. This was established in 1825 by Dr. John Adam, a student of Professor Robert Jameson, who dissected a specimen and found the two-layered pouch filled mainly with air.[22] The only possible confusable species in the region is the smaller lesser adjutant (Leptoptilos javanicus), which lacks a pouch, prefers wetland habitats, has a lighter grey skull cap, a straighter edge to the upper mandible, and lacks the contrast between the grey secondary coverts and the dark wings.[15][23][14]

Like others storks, it lacks intrinsic muscles in the syrinx[24] and produces sound mainly by bill-clattering, although low grunting, mooing or roaring sounds are made especially when nesting.[2][14][25] The bill-clattering display is made with the bill raised high and differs from that of the closely related African marabou which holds the bill pointed downwards.[15][26]

This species was once a widespread winter visitor in the riverine plains of northern India. However, their breeding areas were largely unknown for a long time until a very large nesting colony was finally discovered in 1877 at Shwaygheen on the Sittaung River, Pegu, Burma. It was believed that the Indian birds bred there.[27][28] This breeding colony, which also included spot-billed pelicans (Pelecanus philippensis), declined in size and entirely vanished by the 1930s.[29] Subsequently, a nest site in Kaziranga was the only known breeding area until new sites were discovered in Assam, the Tonle Sap lake and in the Kulen Promtep Wildlife Sanctuary. In 1989, the breeding population in Assam was estimated at 115 birds,[29][30][31][32] and between 1994 and 1996 the population in the Brahmaputra valley was considered to be about 600.[33][34] A small colony with about 35 nests was discovered near Bhagalpur in 2006. The number increased to 75 nests in 2014.[1][35] Fossil evidence suggests that the species possibly (since there were several other species in the genus that are now extinct) occurred in northern Vietnam around 6000 years ago.[36]

During the non-breeding season, storks in the Indian region disperse widely, mainly in the Gangetic Plains. Sightings from the Deccan region are rare.[38] Records of flocks from further south, near Mahabalipuram, have been questioned.[29][39] In the 1800s, adjutant storks were extremely common within the city of Calcutta during the summer and rainy season. These aggregations along the Ghats of Calcutta, however, declined and vanished altogether by the early 1900s. Improved sanitation has been suggested as a cause of their decline.[23][14][40] Birds were recorded in Bangladesh in the 1850s, breeding somewhere in the Sundarbans, but have not been recorded subsequently.[41][42][43]

The greater adjutant is usually seen singly or in small groups as it stalks about in shallow lakes or drying lake beds and garbage dumps. It is often found in the company of kites and vultures and will sometimes sit hunched still for long durations.[14] They may also hold their wings outstretched, presumably to control their temperature.[44] They soar on thermals using their large outstretched wings.[2]

The greater adjutant breeds during winter in colonies that may include other large waterbirds such as the spot-billed pelican. The nest is a large platform of twigs placed at the end of a near-horizontal branch of a tall tree.[27] Nests are rarely placed in forks near the center of a tree, allowing the birds to fly easily from and to the nests. In the Nagaon nesting colony in Assam, tall Alstonia scholaris and Anthocephalus cadamba were favourite nest trees.[45] The beginning of the breeding season is marked by several birds congregating and trying to occupy a tree. While crowding at these sites, male birds mark out their nesting territories, chasing away others and frequently pointing their bill upwards while clattering them. They may also arch their body and hold their wings half open and drooped. When a female perches nearby, the male plucks fresh twigs and places it before her. The male may also grasp the tarsus of the female with the bill or hold his bill close to her in a preening gesture. A female that has paired holds the bill and head to the breast of the male and the male locks her by holding his bill over her neck. Other displays include simultaneous bill raising and lowering by a pair. The clutch, usually of three or four white eggs,[27] is laid at intervals of one or two days and incubation begins after the first egg is laid. Both parents incubate[46] and the eggs hatch at intervals of one or two days, each taking about 35 days from the date of laying. Adults at the nest have their legs covered with their droppings and this behaviour termed as urohidrosis is believed to aid in cooling during hot weather. Adults may also spread out their wings and shade the chicks. The chicks are fed at the nest for about five months.[47] The chicks double in size in a week and can stand and walk on the nest platform when they are a month old. At five weeks, the juveniles leap frequently and can defend themselves. The parent birds leave the young along for longer periods at nest at this stage. The young birds leave the nest and fly around the colony when about four months but continue to be fed occasionally by the parents.[17]

The greater adjutant is omnivorous and although mainly a scavenger, it preys on frogs and large insects and will also take birds, reptiles and rodents. It has been known to attack wild ducks within reach, swallowing them whole.[48] Greater adjutants also capture many fish, with 36 fish prey species documented in Assam, and many fish taken were large, weighing about 2 to 3 kg (4.4 to 6.6 lb).[49] Their main diet however is carrion, and like the vultures their bare head and neck is an adaptation. They are often found on garbage dumps and will feed on animal and human excreta.[50] In 19th-century Calcutta, they fed on partly burnt human corpses disposed along the Ganges river.[51] In Rajasthan, where it is extremely rare, it has been reported to feed on swarms of desert locusts (Schistocerca gregaria)[52] but this has been questioned.[39]

At least two species of bird lice, Colpocephalum cooki[53] and Ciconiphilus temporalis[54] have been found as ectoparasites. Healthy adult birds have no natural predators, and the only recorded causes of premature mortality are due to the direct or indirect actions of humans; such as, poisoning, shooting, or electrocution such as when the birds accidentally fly into telephone lines.[33] Captive birds have been found to be susceptible to avian influenza, (H5N1) and a high mortality rate was noted at a facility in Cambodia, with two-thirds of infected birds dying.[55] The longest recorded life span in captivity was 43 years.[56]

Loss of nesting and feeding habitat through the draining of wetlands, pollution and other disturbances, together with hunting and egg collection in the past has caused a massive decline in the population of this species. The world population was estimated at less than 1,000 individuals in 2008. The greater adjutant is listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.[1]

Conservation measures have included attempts to breed them in captivity and to reduce fatalities to young at their natural nesting sites.[47][57] Nearly 15% of the chicks are killed when they fall off the nests and die of starvation, so some conservationists have used nets positioned below the nests to prevent injuries to falling young. These fallen birds are then fed and raised in enclosures for about five months and then released to join their wild siblings.[17]

In Kamrup district, Assam, which is home to one of the few large colonies of greater adjutants, outreach efforts including cultural and religious programming, especially aimed at village women, have rallied residents to conserve the birds. The locals, who formerly regarded the birds as pests, now see the storks as special and take pride in protecting them and the trees in which they breed. Locals have even added prayers for the safety of the storks to hymns, and included stork designs to the motifs used in traditional weaving. Similar measures have been used with success in other parts of India where adjutants breed.[58]

Aelian described the bird in 250 AD in his De Natura Animalium as the kilas (κηλας), a large bird from India with a crop that looks like a leather bag.[59] Babur described it in his memoirs under the name of ding.[60] In Victorian times the greater adjutant was known as the gigantic crane and later as the Asiatic marabou. It was very common in Calcutta during the rainy season and large numbers could be seen at garbage sites and also standing on the top of buildings. In Bihar, the bird is associated with the mythical bird garuda.[35] Its name hargila in Bengal and Assam is said to be derived from the Sanskrit roots had for "bone" and gila – "to swallow"- and describes the bird as a "bone swallower".[61][62] John Latham used the Latinized form as the species epithet in the binomial name, Ardea argala.[63] Young British soldiers were known to harass these birds for fun, even blowing up birds by feeding them meat containing bones packed with a cartridge and fuse.[64] The birds in Calcutta were considered to be efficient scavengers and an act was passed to protect them. Anyone who injured or killed a bird had to pay a hefty fine of fifty rupees.[65][66][67] The coat of arms of the city of Calcutta issued through two patents on 26 December 1896 included two adjutant birds with serpents in their beaks and charged on their shoulder with an Eastern Crown as supporters. The motto read "Per ardua stabilis esto", Latin for "steadfast through trouble".[68] The arms were included in the logo of official bodies such as the Calcutta Municipal Corporation and the Calcutta Scottish regiment.[69] Captured birds, probably from Calcutta, reached menageries in Europe during this period.[70][71][72][73]

The undertail covert feathers taken from adjutant were exported to London during the height of the plume trade under the name of Commercolly (or Kumarkhali, now in Bangladesh) or "marabout".[74] Since the birds were protected by law, plume collectors would ambush the birds roosting atop buildings, grabbing their undertail feathers which would come off when the birds took to flight. Along with egret plumes, these were the most valuable of feather exports.[75] Specimens of tippets, victorines and boas made from these feathers were displayed at the Great Exhibition of 1851.[76]

An Indian myth recorded by the Moghul emperor Babur was that a magic "snake-stone" existed inside the skull of the bird, being an antidote for all snake venoms and poisons.[15][77] This "stone" was supposed to be extremely rare as it could only be obtained by a hunter with great skill, for the bird had to be killed without letting its bill touch the ground since that would make the "stone" evaporate instantly. Folk-medicine practitioners believed that a piece of stork flesh chewed daily with betel could cure leprosy.[78]

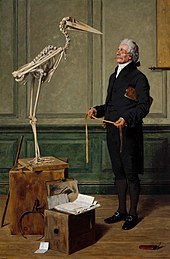

The English artist Henry Stacy Marks (1829-1888) took a special interest in birds. Many of his paintings were based on birds in the London Zoo with several depicting greater adjutants including Convocation (1878), Science is Measurement (1879), Half hours at the Zoo, and An Episcopal Visitation.[79]

The greater adjutant (Leptoptilos dubius) is a member of the stork family, Ciconiidae. Its genus includes the lesser adjutant of Asia and the marabou stork of Africa. Once found widely across southern Asia and mainland southeast Asia, the greater adjutant is now restricted to a much smaller range with only three breeding populations; two in India, with the largest colony in Assam, a smaller one around Bhagalpur; and another breeding population in Cambodia. They disperse widely after the breeding season. This large stork has a massive wedge-shaped bill, a bare head and a distinctive neck pouch. During the day, it soars in thermals along with vultures with whom it shares the habit of scavenging. They feed mainly on carrion and offal; however, they are opportunistic and will sometimes prey on vertebrates. The English name is derived from their stiff "military" gait when walking on the ground. Large numbers once lived in Asia, but they have declined (possibly due to improved sanitation) to the point of endangerment. The total population in 2008 was estimated at around a thousand individuals. In the 19th century, they were especially common in the city of Calcutta, where they were referred to as the "Calcutta adjutant" and included in the coat of arms for the city. Known locally as hargila (derived from the Assamese words "har" means bone and "gila" means swallower, thus "bone-swallower") and considered to be unclean birds, they were largely left undisturbed but sometimes hunted for the use of their meat in folk medicine. Valued as scavengers, they were once depicted in the logo of the Calcutta Municipal Corporation.

La Argalo, Argala marabuo aŭ Hinda marabuo (Leptoptilos dubius), estas birdospecio membro de la familio de cikonioj nome Cikoniedoj. Ties genro inkludas ankaŭ la speciojn de la Azia marabuo kaj de la Afrika marabuo. Iam troviĝis amplekse tra suda Azio, ĉefe en Hindio de kio la nomo Hinda marabuo, sed ankaŭ etende oriente al Borneo, kaj nun estas limigita al multe pli malgranda teritorio kun nur du malgrandaj reproduktaj populacioj; en Barato kun la plej granda kolonio en Asamo kaj la alia en Kamboĝo. Populacioj disiĝas post la reprodukta sezono. Iam vivis grandaj nombroj en Azio, sed ili grande malpliiĝis, eble pro plibonigita higieno, ĝis punkto ke ili iĝis endanĝerita. La totala populacio en 2008 estis ĉirkaŭkalkulata nur je ĉirkaŭ milo da individuoj. En la 19a jarcento, ili estis speciale komunaj en la urbo Kalkato, kie ili estis nomataj "Calcutta Adjutant" (milita helpoficiro). Konataj surloke kiel Hargila (de kio Argalo, devena el la sanskrita vorto por "ostenglutanto") kaj konsiderataj malpuraj birdoj, ili estis dumlonge lasataj neĝenate sed foje ĉasataj por la uzado de ties viando en populara medicino. Valorataj kiel kadavromanĝantoj, ili estis iam uzataj kiel simbolo de la kalkata municipo.

Tiu granda cikonio havas amasan kojnforman bekon, nudan (senpluman) kapon kaj distingan kolsakon (gorĝosako). Dumtage ili ŝvebas sur termikoj kun vulturoj kun kiuj ili kunhavas kutimaron de kadavromanĝo. Ili manĝas ĉefe kadavraĵojn kaj rubaĵojn; tamen ili estas oportunemaj kaj foje predas vertebrulojn.

La Argalo estas granda birdo, stare alta 145–150 cm. La averaĝa longo estas 136 cm kaj averaĝa enverguro estas de 250 cm. Neniom oni publikigis pri la pezo de la naturaj birdoj, sed la Argalo estas inter la plej grandaj el vivantaj cikonioj, kun publikitaj mezuroj koincide kun tiuj de la Jabiruo, la Selbekulo kaj la Marabuo. Junuloj en kaptiveco pezis 8 al 11 kg.[1] La granda beko, kiu estas averaĝe 32.2 cm longa, estas kojnforma kaj helgriza kun pli malhela bazo. La enverguro averaĝas 80.5 cm, la vosto 31.8 cm kaj la tarso 32.4 cm longaj. Kun la escepto de la tarsa longo, la standardaj mezuroj de la Argalo estas averaĝe pli grandaj ol tiuj de aliaj specioj de cikonioj.[2] Blanka kolumo baze de ties nuda flavec- al ruĝec-haŭta kolo havigas vulturecan aspekton. En la reprodukta sezono, la sako kaj kolo iĝas briloranĝaj kaj la supraj femuroj de la grizaj kruroj iĝas ruĝecaj. Plenkreskuloj havas malhelajn flugilojn kiuj kontrastas kun helgrizaj duarangaj flugilkovriloj. La subaj partoj estas blankecaj kaj ambaŭ seksoj estas nedistingeblaj en naturo.

Junuloj estas iome senkolora versio de plenkreskulo. La penda pufigebla gorĝosako konektas al aerpasiloj kaj ne estas konektata kun la digesta sistemo. Ties preciza funkcio estas nekonata, sed ĝi ne rilatas al manĝostokado kiel oni supozis foje.

La ununura konfuzebla specio en la regiono estas la Azia marabuo, kiu ne havas sakon, preferas habitatojn de humidejoj, havas pli helgrizan kronon, pli rektan (ne subenkurban) bordon de supra makzelo kaj ne havas la kontraston inter la grizaj duarangaj kovriloj kaj la malhelaj flugiloj.[3][4][5]

Kiel ĉe aliaj cikonioj, ĝi ne havas voĉajn muskolojn kaj produktas sonon ĉefe per bekofrapado, kvankam ili faras ankaŭ mallaŭtajn gruntojn, muĝojn aŭ rorojn ĉefe dum nestumado.[6][5][7] La bekofrapada memmontrado estas farata per altelevata beko kaj diferencas el tiu de la tre proksima rilata Afrika marabuo kiu tenas la bekon suben.[3][8]

John Latham verkis pri la birdo trovata en Kalkato baze sur priskriboj de la verko de Ives "Voyage to India" publikita en 1773 kaj inkludita en ilustraĵo en la unua suplemento al lia "General Synopsis of Birds". La ilustraĵo estis bazata sur pentraĵo de la kolekto de Lady Impey kaj Latham nomis la birdon Giganta gruo kaj inkludis observojn de afrika veturinto nome Smeathman kiu priskribis similan birdon el okcidenta Afriko. Johann Friedrich Gmelin uzis la priskribon de Latham kaj priskribis la hindian birdon kiel Ardea dubia en 1789 dum Latham poste uzis la nomon Ardea argala por la hindia birdo. Temminck uzis la nomon de Ciconia marabou en 1824 baze sur la loka nomo uzata en Senegalio por la afrika birdo kaj tio estis ankaŭ aplikita al la hindia specio. Tio kondukis al konsiderinda konfuzo inter la afrika kaj la hindia specioj.[9][10] La Marabuo de Afriko ŝajnas iome pli simila sed ties disaj distribuadaj teritorioj, diferencoj en bekostrukturo, plumaro, kaj memmontrada kutimaro subtenas ties traktado kiel separataj specioj.[11]

Plej cikonioj flugas havante kolon etende, sed la tri specioj de Leptoptilos kuntiras siajn kolojn dumfluge kiel ardeoj faras, eble pro la fortika beko.[5] Dum piedirado surgrunde, ĝi havas tre rektan sintenon el kiu devenas la nomo de "adjutant" (adjutanto aŭ helpoficiro).[3]

Tiu specio estis iam disvastigita en la ĉeriveraj ebenaĵoj de norda Barato, tamen ties reproduktaj areoj estis dumlonge nekonataj ĝis kiam oni malkovris tre grandan nestokolonion en 1877 en Shwaygheen ĉe la rivero Sittaung, Pegu, Birmo, kaj oni supozis, ke la hindiaj birdoj reproduktiĝas tie.[12][13] Tiu reprodukta kolonio, kiu inkludis ankaŭ la specion de la Makulbeka pelikano, malpliiĝis kaj poste tute formortis en la 1930-aj jaroj.[14] Sekve, nestoloko en Kaziranga estis la ununura konata reprodukta areo ĝis kiam oni malkovris novajn lokojn en Asamo, nome en lago Tonlesapo kaj en la Naturrezervejo Kulen Promtep. En 1989, la reprodukta populacio en Asamo estis ĉirkaŭkalkulata je ĉirkaŭ 115 birdoj[14][15][16][17] kaj inter 1994 kaj 1996 la populacio en la valo Brahmaputro estis konsiderata de ĉirkaŭ 600.[18][19] Oni malkovris malgrandan kolonion kun ĉirkaŭ 35 nestoj ĉe Bagalpur en 2006.[20][21]

For de la reprodukta sezono, la cikonioj de la hindia regiono disiĝas amplekse, ĉefe en la Gangaj Ebenaĵoj kaj krome estas ankaŭ raraj registroj el la regiono Dekka.[22] Oni pridubis registrojn de aroj el pli sudo ĉe Mahabalipuram.[14][23] En la 1800-aj jaroj, la Argaloj esti tre komunaj ene de la urbo Kalkato dum la somero kaj la pluvsezono. Tiuj koncentroj laŭlonge de la riverdeklivoj de Kalkato tamen malpliiĝis kaj malaperis komence de la 1900-aj jaroj. Plibonigita higienkondiĉaro estis sugestita kiel kaŭzo de ties malpliiĝo.[4][5][24] Birdoj estis registritaj en Bangladeŝo en la 1850-aj jaroj, reprodukte ie ĉe Sundarbanoj, sed ne estis registritaj poste.[25][26][27]

La Argalo estas kutime vidata sola aŭ en malgrandaj grupoj dum ĝi vagadas ĉe neprofundaj lagoj aŭ ĉe sekiĝantaj lagejoj kaj rubejoj. Ĝi ofte troviĝas kun milvoj kaj vulturoj kaj foje staras kurbadorse dumlonge.[5] Ili povas ankaŭ malfermi siajn flugilojn, plej verŝajne por kontroli sian temperaturon.[29] Ili ŝvebas sur termikoj uzante siajn grandajn etendajn flugilojn.[6]

La Argalo reproduktiĝas dum vintro en kolonioj kiuj povas inkludi aliajn grandajn akvobirdojn kiaj la Makulbeka pelikano. La nesto estas granda platformo el bastonetoj situanta ĉe la fino de preskaŭ horizontala branĉo de alta arbo.[12] Nestoj estas rare lokitaj en forkoj kaj libera kanopea pinto permesas la birdojn flugi facile el kaj al la nestoj. En la nestokolonio de Nagaon en Asamo, altaj arboj Alstonia scholaris kaj Anthocephalus cadamba estis favorataj nestarboj.[30] La komenco de la reprodukta sezono estas markata de kelkaj birdaj koncentroj kaj klopodoj okupi arbon. Dum ariĝo ĉe tiuj lokoj, maskloj markas siajn nestajn teritoriojn, forpelante aliulojn kaj ofte indike per siaj bekoj supren dum bekofrapado. Ili povas ankaŭ arkigi siajn korpojn kaj tenas siajn flugilojn duonmalferme kaj subenigite. Kiam ino ripoziĝas proksime, la masklo plukas freŝan bastoneton kaj lokas ĝin antaŭ ŝi. La masklo povas ankaŭ alpreni la tarson de ino per sia beko aŭ tenas sian bekon proksime al ŝi kun sinteno de plumaranĝado. Ino kiu pariĝis metas sian bekon kaj kapon al la brusto de la masklo kaj la masklo prenas ŝin per meto de sia beko super ŝia kolo. Aliaj memmontradaj ceremonioj estas samtempa beko-levado kaj mallevado fare de la paro.

La ovaro, kutime de 3 aŭ 4 blankaj ovoj,[12] estas demetata laŭ intertempoj de unu aŭ du tagoj kaj kovado komencas post la ovodemeto de la unua ovo. Ambaŭ gepatroj kovas[31] kaj eloviĝo okazas ankaŭ je intertempoj de unu aŭ du tagoj, ĉiu post ĉirkaŭ 35 tagojn post la ovodemeto. Plenkreskuloj ĉe nestoj havas siajn krurojn kovritajn el fekaĵoj kaj tiu kutimaro termine kiel urohidrozo oni supozas, ke helpas al malvarmigo dum varma vetero. Plenkreskuloj povas ankaŭ etendi siajn flugilojn por ombroŝirmi la idojn. La idoj estas manĝigataj ĉeneste dum ĉirkaŭ kvin monatoj.[32]

La Argalo estas ĉiomanĝanto kaj kvankam estas ĉefe kadavromanĝanto, ĝi foje predas ranojn kaj grandajn insektojn kaj eĉ kaptas birdojn, reptiliojn kaj rodulojn. Ili povas ataki atingeblajn naturajn anasojn kaj engluti ilin entute.[33] Ties ĉefa dieto tamen estas kadavraĵoj kaj kiel ĉe vulturoj ties nudaj (senplumaj) kapo kaj kolo estas adapto. Ili troviĝas ofte ĉe rubejoj kaj manĝas animalajn kaj homajn fekaĵojn.[34] En Kalkato en la 19a jarcento ili manĝis parte bruligitajn homajn kadavraĵojn disponigitajn laŭlonge de la rivero Gango.[35] En Raĝastano, kie ĝi estas tre rara, oni registris ĝin manĝe svarmojn de dezertaj akridoj (Schistocerca gregaria)[36] sed tio estis pridubita.[23]

Oni trovis almenaŭ du speciojn de birdolaŭsoj, Colpocephalum cooki[37] kaj Ciconiphilus temporalis[38] kiel ektoparazitoj. Sanaj plenkreskuloj ne havas naturajn predantojn, kaj la ununuraj registritaj kaŭzoj de tro frua morto estas pro rekta aŭ nerekta agado de homoj; kiaj venenado, pafado aŭ elektrofrapo kiam la birdoj akcidente flugas kontraŭ altaj elektraj kabloj.[18] Oni trovis, ke kaptivaj birdoj povas suferi pro birda gripo (H5N1) kaj oni notis altan mortindicon ie en Kamboĝo, kie du trionoj de infektitaj birdoj mortis.[39] La plej londaŭra registrita vivodaŭro en kaptiveco estis de 43 jaroj.[40]

Perdo de nesto- kaj manĝohabitato pro sekigado de humidejoj, poluado kaj ĝenado, kune kun ĉasado kaj ovokolektado en pasinto kaŭzis amasan malpliiĝon de la populacio de tiu specio. La monda populacio estis ĉirkaŭkalkulata je malpli da 1,000 individuoj en 2008. La Argalo estis taksata kiel Endanĝerita en la IUCN Ruĝa Listo de Minacataj Specioj.[41]

Konservadaj klopodoj celis bredi ilin kaptivece kaj malpliigi mortojn de junuloj ĉe ties naturaj nestolokoj.[32][42] Preskaŭ 15% el idoj estas mortigataj kiam ili elfalas el la nestoj kaj mortas pro malsatego, kaj tiele konservadistoj metas retojn sub la nestoj por eviti vundojn al falintaj junuloj kaj poste portas tiujn falitajn birdojn al birdejoj kie ili restas dum ĉirkaŭ kvin monatoj antaŭ liberigi ilin por kunigi al ties naturaj parencoj.[1]

En viktoria epoko la Argalo estis konata kiel la Giganta gruo kaj poste kiel la Azia marabuo. Ĝi estis tre komuna en Kalkato dum la pluvsezono kaj oni povis vidi grandajn nombrojn ĉe rubejoj kaj ankaŭ stare sur pintoj de konstruaĵoj. Ties loka nomo hargila devenas el sanskrita hadda-gilla, kio signifas "osto-manĝanto",[43] kaj John Latham donis al la specio la dunoman nomon, Ardea argala.[44] Tiam oni kredis, ke ĝi estas protektata de la animoj de mortintaj brahmanoj. Tiuj birdoj en la urbo Kalkato estis konsiderataj kiel efikaj kadavromanĝantoj kaj oni aprobis leĝon por protekti ilin: ĉiu ajn kiu mortigis tiun birdon devis pagi monpunon de kvindek rupiojn.[45][46][47] La malnova simbolo de la Kalkata Municipa Konsilantaro inkludis du Argalojn frontantajn unu la alian.[48] Kaptitaj birdoj, probable el Kalkato atingis birdejojn en Eŭropon dum tiu periodo.[49][50][51][52]

Hindia mito registrita de la mogola imperiestro Babur estis ke magia "serpento-ŝtono " ekzistis ene de la kranio de tiu birdo, kaj funkciis kiel kontraŭveneno kontraŭ ĉiuj venenoj el serpentoj.[3][53] Tiu "ŝtono" supozeble estis tre rara ĉar estis akirebla nur de ĉasisto ege lerta, ĉar tiu birdo estu mortigata evitante ke ties beko tuŝu la grundon ĉar tiukaze la "ŝtono" malaperus subitege. Popularaj medicinistoj kredis ke peco de marabua viando maĉita ĉiutage kun betelo kuracas lepron.[54]

La Argalo, Argala marabuo aŭ Hinda marabuo (Leptoptilos dubius), estas birdospecio membro de la familio de cikonioj nome Cikoniedoj. Ties genro inkludas ankaŭ la speciojn de la Azia marabuo kaj de la Afrika marabuo. Iam troviĝis amplekse tra suda Azio, ĉefe en Hindio de kio la nomo Hinda marabuo, sed ankaŭ etende oriente al Borneo, kaj nun estas limigita al multe pli malgranda teritorio kun nur du malgrandaj reproduktaj populacioj; en Barato kun la plej granda kolonio en Asamo kaj la alia en Kamboĝo. Populacioj disiĝas post la reprodukta sezono. Iam vivis grandaj nombroj en Azio, sed ili grande malpliiĝis, eble pro plibonigita higieno, ĝis punkto ke ili iĝis endanĝerita. La totala populacio en 2008 estis ĉirkaŭkalkulata nur je ĉirkaŭ milo da individuoj. En la 19a jarcento, ili estis speciale komunaj en la urbo Kalkato, kie ili estis nomataj "Calcutta Adjutant" (milita helpoficiro). Konataj surloke kiel Hargila (de kio Argalo, devena el la sanskrita vorto por "ostenglutanto") kaj konsiderataj malpuraj birdoj, ili estis dumlonge lasataj neĝenate sed foje ĉasataj por la uzado de ties viando en populara medicino. Valorataj kiel kadavromanĝantoj, ili estis iam uzataj kiel simbolo de la kalkata municipo.

Tiu granda cikonio havas amasan kojnforman bekon, nudan (senpluman) kapon kaj distingan kolsakon (gorĝosako). Dumtage ili ŝvebas sur termikoj kun vulturoj kun kiuj ili kunhavas kutimaron de kadavromanĝo. Ili manĝas ĉefe kadavraĵojn kaj rubaĵojn; tamen ili estas oportunemaj kaj foje predas vertebrulojn.

El marabú argala[1] (Leptoptilos dubius) es una especie de ave ciconiforme de la familia Ciconiidae de gran tamaño en peligro de extinción, ya que se halla solo en Assam (India) y Camboya, con un total de menos de 1000 parejas.[2]

El marabú argala (Leptoptilos dubius) es una especie de ave ciconiforme de la familia Ciconiidae de gran tamaño en peligro de extinción, ya que se halla solo en Assam (India) y Camboya, con un total de menos de 1000 parejas.

Leptoptilos dubius Leptoptilos generoko animalia da. Hegaztien barruko Ciconiidae familian sailkatua dago.

Leptoptilos dubius Leptoptilos generoko animalia da. Hegaztien barruko Ciconiidae familian sailkatua dago.

Leptoptilos dubius

Le marabout argala (Leptopilos dubius), parfois nommé "grand adjudant", est une espèce d'échassier de la famille des Ciconiidae.

Il niche dans le sud de l'Asie, du Pakistan à l'Inde, ainsi que dans l'est du Sri Lanka et à Bornéo. Deux petites populations ont été identifiées dans l'Assam et au Cambodge. En hiver, il migre vers le sud, au Vietnam, en Thaïlande ou en Birmanie.

Le marabout argala est un immense oiseau mesurant de 130 à 150 cm de hauteur et de 240 à 290 cm d'envergure. S'il n'y a jamais eu de grandes campagnes de pesage des oiseaux sauvages, il est probablement le plus lourd de tous les échassiers. Son dos et ses ailes sont de couleur noire mais son ventre et le dessous de sa queue sont gris pâle. La tête et le cou roses sont déplumés comme ceux des vautours. Le bec jaune est long et massif. Les jeunes ont des couleurs plus ternes que leurs parents.

La plupart des grands échassiers volent avec le cou déployé mais le Marabout argala, comme les autres espèces du genre Leptoptilos, vole avec le cou rétracté tels les hérons.

Le marabout argala niche dans les régions humides. Il construit un grand nid de branchages dans les arbres et pond de deux à quatre œufs, couvés à tour de rôle par les deux parents pendant 28 à 30 jours jusqu'à éclosion. Ces nids forment souvent de petites colonies.

Le marabout argala comme nombre de ses parents se nourrit essentiellement de grenouilles ou de gros insectes mais aussi d'oisillons, de lézards ou de rongeurs. Il mange occasionnellement des charognes, occupation pour laquelle sa tête et son cou dénudés sont parfaitement adaptés, ou encore pille les décharges d'ordures humaines.

La perte de ses habitats de nidification et d'alimentation par l'agriculture, l'urbanisation ou la pollution, la chasse et le ramassage des œufs a causé un déclin massif de l'espèce. La population totale est estimée à moins de 1000 individus. Le marabout argala est classé espèce menacée sur la liste rouge de l'UICN.

Leptoptilos dubius

Le marabout argala (Leptopilos dubius), parfois nommé "grand adjudant", est une espèce d'échassier de la famille des Ciconiidae.

Il marabù asiatico (Leptoptilos dubius (Gmelin, 1789)) è una specie della famiglia dei Ciconiidi (Ciconiidae). Al suo genere appartengono anche il marabù minore dell'Asia e il marabù dell'Africa. Un tempo diffuso in gran parte dell'Asia meridionale, specialmente in India, ma presente ad est fino al Borneo, il marabù asiatico è ora relegato a un areale molto più piccolo, con appena tre popolazioni nidificanti: due in India, una più numerosa nell'Assam e una più piccola nei dintorni di Bhagalpur, e una in Cambogia. Una volta terminata la stagione della nidificazione, tuttavia, la specie si disperde su un areale più ampio. Questa grossa cicogna ha un massiccio becco a forma di cuneo, una testa glabra e una caratteristica sacca sul collo. Durante il giorno è solito librarsi sulle correnti ascensionali assieme agli avvoltoi, con i quali condivide le abitudini spazzine. Si nutre soprattutto di carogne e scarti di macelleria, ma è una specie opportunista che alle volte cattura prede vertebrate. Deve il nome inglese di adjutant, cioè «aiutante», alla sua rigida andatura «militare» quando cammina al suolo. In passato in Asia era presente un gran numero di questi animali, ma da allora la popolazione è crollata drasticamente (forse anche a causa della messa in atto di programmi di sanificazione), al punto che oggi la specie è in pericolo di estinzione. Nel 2008 la popolazione complessiva venne stimata in circa un migliaio di individui. Nel XIX secolo erano particolarmente comuni nella città di Calcutta: ci si riferiva ad essi come Calcutta adjutant e figuravano addirittura sullo stemma della città. Conosciuti localmente come hargila (un termine derivato dalle parole bengali-assamesi che significano «mangiatore di ossa») e considerati animali impuri, erano per lo più lasciati indisturbati, ma a volte venivano cacciati per l'impiego della loro carne nella medicina popolare. Apprezzati come spazzini, una volta erano raffigurati nel logo della Calcutta Municipal Corporation.

Il marabù asiatico è un uccello imponente, alto fino a 145-150 cm. La sua lunghezza media è di 136 cm e l'apertura alare di 250 cm. Anche se non sono mai stati pubblicati dati sul peso degli esemplari selvatici, il marabù asiatico è una delle cicogne più grandi del mondo: le sue dimensioni sono paragonabili a quelle dello jabirù (Jabiru mycteria), della cicogna becco a sella (Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis) e del marabù africano (Leptoptilos crumeniferus). Esemplari giovani allevati in cattività pesavano tra gli 8 e gli 11 kg[4]. Un esemplare cresciuto in cattività dopo essere rimasto ferito in seguito alla distruzione del nido pesava 4,71 kg quando era un nidiaceo e 8 kg al raggiungimento della maturità sessuale, quando era pronto per essere rilasciato in natura[5]. Al confronto, la cicogna selvatica più pesante di cui siamo a conoscenza era un marabù africano del peso di 8,9 kg: presso questa specie le femmine pesano 4-6,8 kg, i maschi 5,6-8,9 kg[6][7]. L'enorme becco, che misura in media 32,2 cm di lunghezza, è a forma di cuneo e di colore grigio, con la base più scura. La corda alare misura 80,5 cm, la coda 31,8 cm e il tarso 32,4 cm. Fatta eccezione per la lunghezza del tarso, tutte le misure standard del marabù asiatico sono generalmente superiori a quelle delle altre specie di cicogna[8]. Un collare di piume bianche alla base del collo glabro, di colore dal giallo al rosso, conferisce a questa specie l'aspetto di un avvoltoio. Durante la stagione riproduttiva, il collo e la sacca assumono una colorazione arancio brillante, mentre la parte superiore delle cosce, che generalmente è grigia come tutto il resto della zampa, diventa rossastra. Gli adulti hanno ali scure sulle quali spicca il grigio chiaro delle copritrici secondarie. La parte ventrale del corpo è biancastra e i sessi sono indistinguibili sul campo. I giovani sono una versione più sbiadita degli adulti. La sacca gonfiabile e pendula è collegata ai sacchi aeriferi, ma non all'apparato digerente. La sua esatta funzione è sconosciuta, ma non serve a immagazzinare il cibo come talvolta è stato creduto. Tale ipotesi venne affermata già nel 1825 dal dottor John Adam, uno studente del professor Robert Jameson, che, dissezionando un esemplare, trovò questa sacca a due strati riempita principalmente d'aria[9]. L'unica specie della regione con cui è possibile confonderlo è il più piccolo marabù minore (Leptoptilos javanicus), che però è privo di sacca, predilige habitat umidi, ha la calotta cranica di un grigio più chiaro, il margine della mandibola superiore più diritto e non presenta il contrasto tra il grigio delle copritrici secondarie e le ali scure[10][11][12].

Come le altre cicogne, è privo di muscoli intrinseci nella siringe[13] e produce suoni soprattutto sbattendo il becco, sebbene emetta anche bassi grugniti, muggiti o ruggiti, soprattutto durante la nidificazione[2][12][14]. Quando sbatte il becco, il marabù asiatico solleva quest'ultimo verso l'alto, mentre il marabù africano, suo parente stretto, lo tiene rivolto verso il basso[10][15].

John Latham scrisse di questo uccello presente a Calcutta basandosi sulle descrizioni fatte da Ives nel suo Voyage to India pubblicato nel 1773 e ne incluse un'illustrazione nel primo supplemento alla sua General Synopsis of Birds. L'illustrazione si basava su un disegno presente nella collezione di Lady Impey. Latham lo chiamò gigantic crane, «gru gigante», e aggiunse le osservazioni di un viaggiatore africano di nome Smeathman che aveva descritto un uccello simile presente nell'Africa occidentale. Johann Friedrich Gmelin, utilizzando la descrizione di Latham, descrisse l'uccello indiano come Ardea dubia nel 1789, mentre Latham, successivamente, lo chiamò Ardea argala. Temminck, nel 1824, usò il nome Ciconia marabou sulla base del nome locale usato in Senegal per indicare l'uccello africano, che venne applicato anche alla specie indiana. Ciò portò a una certa confusione tra la specie africana e indiana[16][17]. Il marabù dell'Africa è simile al marabù asiatico sotto molti aspetti, ma il loro areale disgiunto, le differenze nella struttura del becco, nel piumaggio e nel comportamento di display ne convalidano il riconoscimento come specie separate[18].

La maggior parte delle cicogne vola con il collo teso in avanti, ma le tre specie di Leptoptilos ritraggono il collo in volo come fanno gli aironi, forse a causa del peso del becco[12]. Quando si sposta sul terreno, questa specie procede con un'andatura rigida che gli ha fatto guadagnare il nome inglese di adjutant, «aiutante»[10].

Una volta questa specie era un visitatore invernale ampiamente diffuso nelle pianure rivierasche dell'India settentrionale. Tuttavia, i siti di nidificazione rimasero sconosciuti per molto tempo, fino a quando, nel 1877, non venne scoperta una colonia nidificante molto numerosa a Shwaygheen, una località vicino a Pegu sul fiume Sittaung, in Birmania. Con la sua scoperta, gli studiosi credettero che gli esemplari indiani si riproducessero qui[19][20]. Questa colonia riproduttiva, nella quale nidificava anche un gran numero di pellicani grigi (Pelecanus philippensis), diminuì sempre più di dimensioni fino a scomparire completamente durante gli anni '30[21]. Successivamente un sito di nidificazione a Kaziranga rimase per molto tempo l'unico territorio riproduttivo noto fino a quando non furono scoperti altri siti nell'Assam, sul lago Tonlé Sap e nel santuario naturale di Kulen Promtep. Nel 1989 la popolazione riproduttiva dell'Assam venne stimata in circa 115 esemplari[21][22][23][24] e tra il 1994 e il 1996 la popolazione nella valle del Brahmaputra venne valutata in circa 600 esemplari[25][26]. Una piccola colonia costituita da circa 35 nidi è stata scoperta vicino a Bhagalpur nel 2006. Il loro numero era salito a 75 nel 2014[1][27]. I resti fossili suggeriscono che la specie forse era presente nel Vietnam settentrionale intorno a 6000 anni fa (anche se non è possibile stabilire con certezza che si trattasse proprio di questa, dal momento che sono vissute altre specie appartenenti a questo genere, oggi estinte)[28].

Al di fuori della stagione riproduttiva, i marabù della regione indiana si disperdono ampiamente sul territorio, specialmente nelle pianure gangetiche. Gli avvistamenti provenienti dalla regione del Deccan sono rari[30]. La validità delle segnalazioni di stormi avvistati molto più a sud, nei pressi di Mahabalipuram, è stata messa in discussione[21][31]. Nel XIX secolo i marabù erano estremamente comuni nella città di Calcutta durante l'estate e la stagione delle piogge. Queste aggregazioni lungo i ghat della città, tuttavia, andarono diminuendo, fino a scomparire del tutto agli inizi del XX secolo. Come possibile causa del loro declino è stato tirato in ballo il miglioramento dei servizi igienico-sanitari[11][12][32]. Negli anni '50 del XIX secolo la presenza di questi uccelli venne segnalata in Bangladesh, dove forse nidificavano da qualche parte nelle Sundarbans, ma da allora non sono più stati avvistati nell'area[33][34][35].

Il marabù asiatico viene avvistato di solito da solo o in piccoli gruppi mentre si aggira in laghi poco profondi, nel letto di laghi asciutti o nelle discariche. Spesso viene visto in compagnia di nibbi e avvoltoi e a volte resta immobile per lunghi periodi[12]. Quando resta immobile può anche tenere le ali aperte, probabilmente per tenere sotto controllo la temperatura del corpo[36]. Quando è in volo, plana sulle correnti ascensionali tenendo le grandi ali spiegate[2].

Il marabù asiatico si riproduce durante l'inverno in colonie che possono ospitare altri grandi uccelli acquatici, come il pellicano grigio. Il nido consiste in una grande piattaforma di ramoscelli posta all'estremità di un ramo quasi orizzontale di un albero alto[19]. Solo raramente esso viene collocato presso le biforcazioni al centro dell'albero, e questo consente agli uccelli di volare facilmente da e verso il nido. Nella colonia riproduttiva di Nagaon, nell'Assam, gli alti Alstonia scholaris e Neolamarckia cadamba erano gli alberi prediletti per costruire il nido[37]. All'inizio della stagione riproduttiva diversi uccelli si rinuiscono insieme e cercano di occupare un albero. Mentre si affollano in questi siti, i maschi dichiarano il possesso del loro nido: scacciano gli altri marabù e spesso sbattono il becco puntandolo verso l'alto. Possono anche inarcare il corpo e tenere le ali semiaperte e abbassate. Quando una femmina si appollaia nelle vicinanze, il maschio raccoglie dei ramoscelli freschi e li mette davanti a lei. Il maschio può anche trattenere il tarso della femmina con il becco o lisciarle il piumaggio con quest'ultimo. Una femmina che si è accompagnata ad un maschio tiene il becco e la testa vicine al petto del maschio e il maschio la blocca tenendole il becco sul collo. Un altro tipo di attività proprio della coppia consiste nel sollevare e abbassare simultaneamente il becco. Le uova, bianche e generalmente in numero di tre o quattro[19], vengono deposte a intervalli di uno o due giorni e covate subito dopo che è stato deposto il primo. Entrambi i genitori partecipano alla cova[38] e le uova si schiudono a intervalli di uno o due giorni, circa 35 giorni dopo essere state deposte. Quando sono nel nido, gli adulti hanno le zampe ricoperte dai propri escrementi: si ritiene che questo comportamento, chiamato uroidrosi, aiuti a rinfrescarli durante la stagione calda. Gli adulti possono anche allargare le ali e fare ombra ai pulcini. Questi vengono nutriti nel nido per circa cinque mesi[39]; raddoppiano le dimensioni di settimana in settimana e possono stare in piedi e camminare sulla piattaforma del nido quando hanno un mese. A cinque settimane, i giovani effettuano frequenti saltelli e sono in grado di difendersi. Raggiunta questa fase dello sviluppo, i genitori iniziano a lasciarli soli nel nido per periodi più lunghi. I giovani lasciano il nido e volano intorno alla colonia quando hanno circa quattro mesi, ma continuano a essere nutriti occasionalmente dai genitori[4].

Il marabù asiatico è onnivoro e, benché sia soprattutto uno spazzino, dà la caccia a rane e grossi insetti, così come a uccelli, rettili e roditori. Attacca le anatre selvatiche che ha a portata di mano e le inghiotte intere[40], e cattura anche molti pesci: nell'Assam sono state documentate ben 36 specie di pesci che figurano sul suo menu, compresi individui di grandi dimensioni, del peso di circa 2-3 kg[41]. Questa specie, tuttavia, si nutre prevalentemente di carogne, e la testa e il collo nudi costituiscono un adattamento a questa dieta, come nel caso degli avvoltoi. Nelle zone in cui abitano è facile trovarli nelle discariche, dove si nutrono anche di escrementi animali e umani[42]. Nella Calcutta del XIX secolo, i marabù si nutrivano dei cadaveri umani parzialmente bruciati disposti lungo il fiume Gange[43]. Secondo alcuni autori, nel Rajasthan, dove sono estremamente rari, si nutrirebbero degli sciami di locuste del deserto (Schistocerca gregaria)[44], ma la validità di tale affermazione è stata messa in dubbio[31].

Almeno due specie di pidocchi, Colpocephalum cooki[45] e Ciconiphilus temporalis[46], sono risultate essere ectoparassiti del marabù asiatico. Gli esemplari adulti in piena salute non hanno predatori naturali e le uniche cause note di mortalità prematura sono dovute ad azioni dirette o indirette dell'uomo, ad esempio avvelenamento, uccisioni con arma da fuoco o elettrocuzione, quando questi uccelli sbattono accidentalmente contro le linee telefoniche[25]. È stato riscontrato che gli esemplari in cattività possono essere colpiti dall'influenza aviaria (H5N1) e presso una struttura in Cambogia si è registrato un alto tasso di mortalità: due terzi degli esemplari infettati, infatti, sono morti[47]. La longevità massima registrata in cattività è stata di 43 anni[48].

La perdita dei terreni di nidificazione e di alimentazione a causa del prosciugamento delle zone umide, dell'inquinamento e di altri fattori antropici, insieme alla caccia e alla raccolta di uova in passato, ha causato un massiccio calo della popolazione di questa specie. Nel 2008 la popolazione complessiva è stata valutata in meno di 1000 individui. Il marabù asiatico è classificato come «specie in pericolo» nella lista rossa della IUCN[1].

Tra le misure di conservazione che sono state prese per scongiurare l'estinzione della specie figurano tentativi di riproduzione in cattività e di riduzione delle vittime tra i giovani presso i siti di nidificazione naturali[39][49]. Dal momento che quasi il 15% dei pulcini rimane ucciso quando cade dal nido, a seguito delle ferite riportate o per inedia, alcuni conservazionisti hanno posizionato delle reti sotto i nidi per impedire che i giovani che cadono si feriscano. Gli uccelli caduti vengono quindi nutriti e allevati in recinti per circa cinque mesi e poi rilasciati in natura, in modo che possano ricongiungersi ai loro fratelli selvatici[4].

Nel distretto di Kamrup, nell'Assam, dove si trova una delle poche grandi colonie rimaste di marabù asiatici, i programmi di sensibilizzazione della popolazione locale, facendo presa anche sulle coscienze culturali e religiose, soprattutto delle donne dei villaggi, hanno ottenuto il successo sperato e ora i residenti hanno fatto fronte comune per proteggere la specie. La gente del posto, che in passato considerava questi uccelli alla stregua di animali nocivi, ora vede i marabù come creature speciali ed è orgogliosa di proteggere loro e gli alberi su cui si riproducono. I locali hanno addirittura aggiunto delle preghiere per la protezione dei marabù ai propri inni e hanno incluso la sagoma di questi animali ai motivi usati nella tessitura tradizionale. Misure simili sono state attuate con successo anche in altre parti dell'India dove i marabù nidificano[50].

Eliano parlò del marabù nel suo De Natura Animalium del 250 d.C.: lo chiamò kilas (κηλας) e lo descrisse come un grosso uccello indiano dal gozzo simile a una sacca di cuoio[51]. Anche Babur ne parlò nelle sue memorie, chiamandolo ding[52]. In epoca vittoriana il marabù asiatico divenne noto inizialmente come gru gigante e solo più tardi come marabù asiatico. Era molto comune a Calcutta durante la stagione delle piogge e si poteva vederne un gran numero presso gli immondezzai o anche in cima agli edifici. Nel Bihar, la specie viene associata al mitologico uccello Garuḍa[27]. Si dice che il nome hargila, con cui è noto in Bengala e Assam, derivi dalle radici sanscrite had, «osso», e gila, «ingoiare», e significherebbe pertanto «mangiatore di ossa»[53][54]. John Latham utilizzò la forma latinizzata del nome come epiteto specifico quando assegnò alla specie il nome scientifico Ardea argala[55]. A quel tempo si credeva che i marabù fossero protetti dalle anime dei bramini morti. I giovani soldati britannici erano soliti molestare questi uccelli per divertimento: in alcuni casi arrivavano perfino a farli saltare in aria dando loro da mangiare pezzi di carne e ossa contenenti una cartuccia dotata di miccia[56]. Essi rimanevano calmi al passaggio dei locali, ma strillavano allarmati non appena vedevano qualcuno che indossava abiti europei[57]. I marabù di Calcutta erano considerati degli efficienti spazzini e fu addirittura promulgata una legge per proteggerli: chiunque avesse ferito o ucciso un marabù doveva pagare una multa di cinquanta rupie[58][59][60]. Lo stemma della città di Calcutta, rilasciato attraverso due brevetti il 26 dicembre 1896, rappresentava due marabù con dei serpenti nel becco e una corona all'antica sulle spalle. Il motto recitava «Per ardua stabilis esto», cioè «risoluto nelle difficoltà» in latino[61]. Lo stemma venne in seguito inserito nel logo di enti ufficiali come la Calcutta Municipal Corporation e il reggimento Calcutta Scottish[62]. Durante questo periodo, alcuni esemplari, provenienti probabilmente da Calcutta, raggiunsero i serragli europei[63][64][65][66]

All'apice del commercio mondiale delle piume, le penne copritrici sottocaudali dei marabù venivano esportate a Londra sotto il nome di Commercolly (o Kumarkhali, dal nome di una località dell'attuale Bangladesh) o «marabout»[67]. Dal momento che questi uccelli erano protetti dalla legge e non potevano essere uccisi, i raccoglitori di piume si avvicinavano di soppiatto ai marabù appollaiati in cima agli edifici, afferrando le piume del sottocoda che si staccavano quando questi prendevano il volo. Insieme alle piume di garzetta, quelle di marabù erano considerate tra le più preziose ad essere esportate[68]. Mantelline, stole e boa fatti con queste piume vennero addirittura esposti alla Grande Esposizione del 1851[69].

Secondo un mito indiano riportato dall'imperatore moghul Babur, all'interno del cranio di questo uccello si troverebbe una «pietra del serpente» magica, antidoto contro tutti i morsi di serpente e altri tipi di veleno[10][70]. Questa «pietra» doveva essere estremamente rara, in quanto un cacciatore poteva impossessarsene solo dando prova di grande abilità: il marabù doveva essere ucciso senza che il suo becco toccasse il suolo, poiché ciò avrebbe fatto evaporare istantaneamente la «pietra». Coloro che facevano affidamento sulla medicina popolare credevano che un pezzo di carne di marabù masticato quotidianamente assieme al betel potesse curare la lebbra[71].