en

names in breadcrumbs

Hoary marmots are mostly herbivorous. Vetches, sedges, fleabanes, fescues, mosses, lichens, and willows collectively comprise about 90% of the overall diet of populations living on the Kenai Peninsula, while populations from mountainous regions prefer flowers and flower heads (Barash 1989, Hansen 1975). Marmot populations from different regions have similar diet-habitat characteristics even if less plant biomass is available. Hoary marmots do not select vegetation in proportion to the amount available, but rather show a preference for certain plants. Hoary marmots spend most of their above-ground time foraging. They appear to prefer each other’s company, feeding in groups. Feeding groups of up to 8 animals can occur. However, these groups are loosely organized and dynamic in terms of membership (Barash 1989).

Plant Foods: leaves; flowers

Primary Diet: herbivore (Folivore )

Hoary marmots are eaten by a variety of predators, including golden eagles, lynx, coyotes, grizzlies, and wolverines. Predator avoidance appears to exert a strong influence on foraging patterns, and marmots have been known to remain in their burrows for many hours following the appearance of a predator (Barash 1989). They also use alarm calls to alert one another if a predator has entered their foraging area.

Known Predators:

Hoary marmots weigh 8 to 10 kg and are from 45 to 57 cm in length, with males being slightly larger than females (Kyle et al. 2007). Tail length is 7 to 25 cm. Their coats are mostly black and white with hoary tips to the fur, base fur color varies geographically (Barash 1989, Hoffmann et al. 1979). They have a white patch between the eyes and across the rostrum, and the tips of their noses are white. Hoary marmots differ from other marmots in that they have black feet. This is the basis of the species’ name caligata, which means “booted” (Hoffmann et al. 1979). They also have a black cap on their head that is larger than similar caps found in other species of marmots. Marmots generally undergo a single annual molt. The onset of the molt varies, but can happen as soon as emergence from hibernation. By midsummer, molting is advanced in all individuals except the young of the year (Barash 1989). Hoary marmots have small eyes and small, rounded, furred ears. They have well-developed claws on their front feet for burrowing and 5 pats on their forepaws, 6 on their hind paws.

Range mass: 8 to 10 kg.

Average length: 50 cm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: male larger

Weight at hibernation is significantly related to overwinter mortality, which is highest among young of the year. Winter mortality during hibernation is often more predictable than predation, and the mortality of males is higher than that of females (Barash 1989).

Range lifespan

Status: captivity: 12.1 (high) years.

Hoary marmots occupy areas with rocky talus slopes and alpine tundra vegetation (Kyle et al. 2007) and dig their burrows in these areas. Burrows provide shelter from predators and weather, marmots spend about 80% of their lives in them (Barash 1989). Entrances to marmot burrows are not easily identified because they simply appear as spaces between and/or under large boulders (Karels et al. 2004). The elevational range of hoary marmot habitats varies latitudinally; they are found at sea level in Alaska and only at higher elevations in the southern portions of their range.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: tundra ; mountains

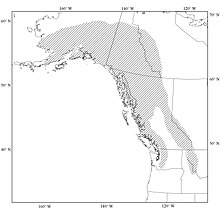

Hoary marmots are one of the most widespread alpine mammals in North America, ranging from Alaska south through northwest Canada to Washington, Idaho, and Montana (Karels et al. 2004). They have a wide distribution in Alaska, including the Alaska Peninsula, Alaska Range, and White Mountains. In Canada, hoary marmots inhabit the Ogilvie Mountains in the Yukon Territory. They are found in the Cascades Mountain range, northern and central Rocky Mountains, the Beaverhead and Flint Creek Mountains of northwestern Montana, and the Salmon River mountains of central Idaho (Hoffmann et al. 1979).

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native )

Hoary marmots are good candidates as indicator species because alpine ecosystems are particularly vulnerable to climate change (Krajick 2004). Compared to other alpine species, they have little commercial value in North America and hardly experience any human-related mortality. Changes in their populations could be indicative of other large-scale impacts. Long-term population dynamics of hoary marmots may also provide an indication of changes in alpine snowpack, plant phenology and abundance, or predators (Karels et al. 2004).

The feces of hoary marmots are important to pikas, which have been observed consuming these droppings. Dried fecal pellets of hoary marmots have been found in haypiles made by pikas (MacDonald and Jones 1987). Marmot feces may be important for soil as well. Soil surrounding marmot burrows is thought to be quite high in nutrients because marmots tend to deposit fecal matter in these areas (Bowman and Seastedt 2001).

Ecosystem Impact: soil aeration

Hoary marmot hides were prized by northwestern Native Americans, mainly for clothing. Marmots were hunted after the molt, and their hides were used in potlatch ceremonies. Their hides were also used as a sort of currency, measuring wealth among Tlingit and Gitksan tribes (Armitage 2003).

Positive Impacts: food ; body parts are source of valuable material

There are no known negative impacts associated with hoary marmots. Hoary marmots inhabit areas with low human population densities.

Hoary marmots have a stable population trend and are considered a species of least concern. The state of Alaska, however, considers two subspecies of hoary marmots to be of conservation concern: Montague Island marmots (M. c. sheldoni) and Glacier Bay marmots (M. c. vigilis). Montague Island marmots were last seen at the turn of the 20th century and are considered a species of concern because of lack of sightings. Because these marmots are endemic to Montague Island, they may face a higher risk of extinction. The state of Alaska also considers Glacier Bay marmots to be a subspecies of concern due to its endemism and presumed small population size. In addition, there is lingering taxonomic uncertainty regarding both of these subspecies.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

Hoary marmot alarm calls tend to be loud, relatively short, and are associated with predators or agitation (Barash 1989, Blumstein and Armitage 1997). Hoary marmots also use visual signals to communicate. The clearest visual signal is an upraised tail, which appears to signal aggression towards other members of the colony (Barash 1989).

Communication Channels: visual ; acoustic

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Recent studies have shown that fecal pellet counts can provide an accurate estimate of group size in hoary marmots, thus allowing for better monitoring of population changes (Karels et al. 2004).

Mating occurs shortly after emergence in the spring. Typical mating behavior involves the male approaching the female, sniffing her (possibly to determine if she is reproductive), then mounting her dorsoventrally. The female, when mounted, lifts her tail and holds it to one side. Successful mounts may last 30 seconds to 8 minutes. Non-reproductive females usually fight against an attempted mount, while reproductive females are more tolerant (Barash 1989). Sniffing, fighting, and chasing are all examples of marmot reproductive behavior. Originally, northern populations of hoary marmots were thought to be predominantly monogamous, while southern populations were thought to be both monogamous and polygynous. Recent studies suggest that mating among hoary marmots is more flexible than previously thought, varying between monogamy and polygyny. This may reflect local variation and resource availability (Kyle et al. 2007).

Mating System: monogamous ; polygynous

Females reproduce every other year, with an average litter size of 3.3, range 2 to 5 (Barash 1989, Armitage 2003). Yearlings remain in their natal colony and disperse the following year as two-year-olds, which is the age of sexual maturity. The reproductive cycle lasts 10 weeks, and gestation lasts about 4 weeks. Estrous in reproductive females occurs about 1 to 2 weeks after emergence from the hibernation and only occurs once yearly (Barash 1989).

Breeding interval: Hoary marmot females breed once every two years, although they go into estrous each year.

Breeding season: Hoary marmots breed in the early spring, shortly after emergence from hibernation.

Range number of offspring: 2 to 5.

Average number of offspring: 3.3.

Average gestation period: 4 weeks.

Average weaning age: 2 weeks.

Average time to independence: 2 years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 2 years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 2 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; viviparous

Average gestation period: 29 days.

Average number of offspring: 4.2.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

Sex: female: 908 days.

As the breeding season progresses, adult males and females become less closely associated. When the young of the year are born, females provide more parental care than males and are the most watchful during the two-week period of their young’s emergence (Barash 1989). Young of the year are born blind and naked, except for vibrissae and short hair on the muzzle, chin, and head. Crawling (backward and forward) and teat seeking are the first movements to occur (Armitage 2003). Young of the year are weaned between the third week of July and the first week of August. Even though adult males are larger than adult females, increases in size are relatively constant between sexes during development. Hair gradually develops from head to tail, and more rapidly on the back than on the belly (Armitage 2003).

Parental Investment: altricial ; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); post-independence association with parents

The hoary marmot (Marmota caligata) is a species of marmot that inhabits the mountains of northwest North America. Hoary marmots live near the tree line on slopes with grasses and forbs to eat and rocky areas for cover.

It is the largest North American ground squirrel and is often nicknamed "the whistler" for its high-pitched warning issued to alert other members of the colony to possible danger. The animals are sometimes called "whistle pigs". Whistler, British Columbia, originally London Mountain because of its heavy fogs and rain, was renamed after these animals to help make it more marketable as a resort.[3] The closest relatives of the species are the yellow-bellied, Olympic, and Vancouver Island marmots, although the exact relationships are unclear.[4][5]

The hoary marmot is a large, bulky, ground squirrel, with short, heavy limbs, and a broad head. Adults range from 62 to 82 cm (24 to 32 in) in total length, including a 17 to 25 cm (6.7 to 9.8 in) tail. The species is sexually dimorphic, with males being significantly larger than females in most subspecies. Because of their long winter hibernation, during which they survive on fat reserves, the weight of the animals varies considerably over the course of the year, from an average of 3.75 kg (8.3 lb) in May to around 7 kg (15 lb) in September, for a fully grown adult.[6] A few fall adult males can commonly range up to a weight of 10 kg (22 lb).[7] The record sized autumn male specimen attained a mass of nearly 13.5 kg (30 lb), possibly the largest size known for any marmot.[8] Going on its average size relative to other marmot species, it is slightly smaller on average than the Olympic marmot, similar in size to the Vancouver marmot and broadly overlaps in size with several lesser-known Asian marmot species as well.[6][9][10][11]

The word "hoary" refers to the silver-gray fur on their shoulders and upper back; the remainder of the upper parts have drab- or reddish-brown fur. The head is black on the upper surface, with a white patch on the muzzle, white fur on the chin and around the lips, and grizzled black or brown fur elsewhere. The feet and lower legs are black, sometimes with white patches on the fore feet. Marmots have long guard hairs that provide most of the visible colour of their pelage, and a dense, soft underfur that provides insulation. The greyish underparts of the body lack this underfur, and are more sparsely haired than the rest of the body.[12] Hoary marmots moult in the early to mid summer.[6]

The feet have slightly curved claws, which are somewhat larger on the fore feet than on the hind feet. The feet have hairless pads, enhancing their grip. The tail is long, slightly flattened, and covered with dense fur. Apart from the larger size of the males, both sexes have a similar appearance. Females have five pairs of teats, running from the pectoral to the inguinal regions.[6]

The hoary marmot predominantly inhabits mountainous alpine environments to 2,500 metres (8,200 ft) elevation, although coastal population also occur at or near sea level in British Columbia and Alaska.[6] Hoary marmots occur from southern Washington and central Idaho north, and are found through much of Alaska south of the Yukon River.[14][6] They live above the tree line, at elevations from sea level to 2,500 metres (8,200 ft), depending on latitude, in rocky terrain or alpine meadows dominated by grasses, sedges, herbs, and Krummholz forest patches.[6] Range maps often erroneously depict hoary marmots occurring north of the Yukon River in Alaska, this region is occupied by the Alaska marmot (M. broweri) and not the hoary marmot.[14] Hoary marmots also occur on several islands in Alaska and fossils dating back to the Pleistocene, including some from islands no longer inhabited by the species.[15]

The three currently recognized subspecies are:

Hoary marmots are diurnal and herbivorous, subsisting on leaves, flowers, grasses, and sedges. Predators include golden eagles, grizzly and black bears, wolverines, coyotes, red foxes, lynxes, wolves, and cougars. They live in colonies of up to 36 individuals, with a home range averaging about 14 hectares (35 acres). Each colony includes a single, dominant, adult male, up to three adult females, sometimes with a subordinate adult male, and a number of young and subadults up to two years of age.[6]

The marmots hibernate seven to eight months a year in burrows they excavate in the soil, often among or under boulders. Each colony typically maintains a single hibernaculum and a number of smaller burrows, used for sleeping and refuge from predators. The refuge burrows are the simplest and most numerous type, consisting of a single bolt hole 1 to 2 metres (3 ft 3 in to 6 ft 7 in) deep. Each colony digs an average of five such burrows a year, and a mature colony may have over a hundred. Sleeping burrows and hibernacula are larger and more complex, with multiple entrances, deep chambers lined with plant material, and stretching to a depth of about 3.5 metres (11 ft). A colony may have up to 9 regular sleeping burrows, in addition to the larger hibernaculum.[16] Many forms of social behaviour have been observed among hoary marmots, including play fighting, wrestling, social grooming, and nose-to-nose touching. Such activity becomes particularly frequent as hibernation approaches. Interactions with individuals from other colonies are less common, and usually hostile, with females chasing away intruders. Hoary marmots are also vocal animals, with at least seven distinct types of calls, including chirps, whistles, growls, and whining sounds.[17] Many of these calls are used as alarms, alerting other animals to potential predators. They also communicate using scent, both by defecation, and by marking rocks or plants using scent glands on their cheeks.[6]

Hoary marmots frequently sun themselves on rocks, spending as much as 44% of their time in the morning doing so, although they will shelter in their burrows or otherwise seek shade in especially warm weather. They forage for the rest of the day, returning to their burrows to sleep during the night.[6]

In areas frequented by people, hoary marmots are not shy. Rather than running away at first sight, they will often go about their business while being watched.

Mating occurs after hibernation, and two to four young are born in the spring. Males establish "harems", but may also visit females in other territories.

Hoary marmots breed shortly after,[18] or even before,[19] their emergence from hibernation burrows in May and in some areas (such as the eastern Cascade foothills of Washington State) as early as February. Courtship consists of sniffing the genital region, followed by mounting, although mounting has also been observed between females. Females typically raise litters only in alternate years, although both greater and lesser frequencies have been reported on occasion.[6][19]

Gestation lasts 25 to 30 days, so the litter of two to five young is born between late May and mid-June.[18] The young emerge from their birth den at three to four weeks of age, by which time they have a full coat of fur and are already beginning to be weaned.[20] The young are initially cautious, but begin to exhibit the full range of nonreproductive adult behavior within about four weeks of emerging from the burrow. Subadults initially remain with their birth colony, but typically leave at two years of age, becoming fully sexually mature the following year.[6]

The hoary marmot (Marmota caligata) is a species of marmot that inhabits the mountains of northwest North America. Hoary marmots live near the tree line on slopes with grasses and forbs to eat and rocky areas for cover.

It is the largest North American ground squirrel and is often nicknamed "the whistler" for its high-pitched warning issued to alert other members of the colony to possible danger. The animals are sometimes called "whistle pigs". Whistler, British Columbia, originally London Mountain because of its heavy fogs and rain, was renamed after these animals to help make it more marketable as a resort. The closest relatives of the species are the yellow-bellied, Olympic, and Vancouver Island marmots, although the exact relationships are unclear.